Chapter 11

![]()

A Fight between Heaven and Hell

Ifeel I need to put a finer point on what I believe the Civil War was all about. Of course, as I have stated, the war was about human freedom and redemption from national sin. But remember why the promised land was created: as a place to build Zion, to build temples, to build the kingdom of God on earth. The broad-brush themes of human freedom and national redemption would naturally support these lofty goals, but it was always these lofty goals that heaven had its eyes on during this great conflict.

Think about this: the Church went from a time when state governments beat, killed, and exiled their people to a time when these same governments formally and officially apologized for their sins and allowed the Saints to rejoin the Union. It went from a time when the federal government sat idly by while Mormons suffered to a time when the federal government awarded one of our prophets the highest honor given to civilians. It went from a time when members of the Church were denied all civil rights to a time when Church members hold the most prominent positions in Congress and are strong candidates for the presidency of the United States. It went from a time when God’s temples were allowed to be burned to the ground to a time when the government called on special police forces to protect the temple from the threat of mobs.1

No event in recent history illustrates this powerful change in America better than the events that occurred in Los Angeles, California, on November 6, 2008. In protest over the Church’s stance on Proposition 8 (California’s marriage amendment), more than one thousand rioters gathered around the Los Angeles Temple, threatening both the sacred edifice and the Saints working therein. Though in days past, the temple might have been left to the will of the mob (as it was with the Kirtland and Nauvoo temples), in this case the American covenant came to the rescue. Police officers in raid gear landed powerfully upon the temple grounds, prepared to defend the building by force if necessary.2 We should not take this for granted. Joseph Smith would not have. He would have been overjoyed to see such protection. He had pled with all his heart for the apathetic nation to provide this protection to the Church. He was completely ignored. The Los Angeles Temple might have burned if that scene had played out in Joseph’s America.

So, what has since happened? How did the Church become elevated from its Nauvoo Temple status (a burned temple) to its Los Angeles Temple status (a rescued temple)? Did America just wake up one day and say, Let’s stop beating up those Mormons; let’s stop enslaving black people; let’s stop burning temples, convents, and synagogues? No! That does not happen.

A prominent journalist recently asked on national television: “How do you go from being the ultimate outcast to the embodiment of the mainstream in two generations? It’s a breathtaking transformation. . . . [Mormons became] the embodiment of what it means to be America.”3 That is a mystery to many. But not to those who understand the scriptures—for it is all spelled out in the prophecies delivered by Joseph Smith. The Lord warned that if America chose not to fulfill its divine mandate as the protectorate of the gospel, then He would, in “hot displeasure” and in “fierce anger,” arise and “come forth out of his hiding place, and in his fury vex the nation;” and “set his hand and seal to change the times and seasons,” that He might “bring to pass [His] act, [His] strange act, and perform [His] work, [His] strange work” (D&C 101:89, 90, 95; 121:12). This, in the end, is what caused that “breathtaking transformation.” It was the war. The people’s unrighteousness pushed God to activate these frightening prophecies for the sake of His kingdom on earth. And the war came. Admittedly, it would take years after the war for the fulness of its fruit to materialize, but the war is what began the process of bringing liberty and salvation to America.

I discussed with you the powerful redemptive change that occurred in the North during those first two years of war. That was Act I of the war. Now, with the Northern heart changed—with its new understanding that this war was a holy war—Act II could begin: the eradication of slavery in all its forms. In hindsight, the plan was perfect. God would convert His army to His cause, then (once they were sufficiently prepared) He would send them to eradicate the evil that persisted in the land. You see, the demon here was always slavery. Once eradication of that evil became the goal and intent of Lincoln and the North, the game changed. At that point, the war became what Lincoln’s contemporary George Washington Julian rightfully (even prophetically) called “a fight . . . between God and the Devil—between heaven and hell!”4

Yes, you say, but what does slavery have to do with the Restoration? My answer: Everything! Said Lincoln: “Slavery is the evil out of which all our other national evils and dangers have come. It has deceived and led us to the brink of ruin, and it must be stopped.”5 If some atrocious thing could socially and politically be done to blacks, it could conceivably be done to anyone. And it was! (Check your Mormon history.) This is perhaps why Frederick Douglass so poignantly declared that “the destiny of the colored American . . . is the destiny of America.”6 It is also why Civil War witness and literary great Ralph Waldo Emerson stated, “I think we must get rid of slavery, or we must get rid of freedom.”7

The institution of slavery had to be abolished.

Once the North began to understand this, the fight with the South was no longer just about saving the Union. It was about eradicating the evil that festered, grew, and proliferated in the Southern system. That said, we should (as Lincoln did) show a degree of sensitivity and compassion toward the South. As in any war, the individual reason each soldier fought varied. For example, many Confederate soldiers fought simply because they were drafted into the fight. Lincoln and his honest friends would allude to the idea that, had they been born in, say, South Carolina, they likely would have worn the gray uniform too. At the same time, however, it feels contrary to history to pretend that the Southern leadership was not fighting to keep slavery intact. The new Republican Party, whose major initiative was antislavery, got one of their own (Lincoln) in the White House. This would scare any society whose lifeblood was slavery. And so the Southern states left. And they fought to preserve a wicked ideal. Once converted to the truth behind the God-ordained mission in the conflict, the North sought to destroy this wicked ideal.8

“As a nation we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except Negroes.’ When the Know-Nothings [anti-immigrant/antiminority party] get control, it will read ‘all men are created equal, except Negroes and foreigners and Catholics.’ When it comes to this, I shall prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.”

—Abraham Lincoln9

If the North could not emerge victorious, the cause of the Restoration would be severely hampered. And this is why: A people cannot support and love a system that enslaves an entire race and not see the effects of such evil spill out in other areas of life. Yes, Southern intent was even darker than the preservation of slavery. Why? Because the ability for the South to enslave blacks provided the justification to do the same to any other group—and Mormons were that other group. The kingdom of God on earth was that other group.

Earlier, I mentioned the work of Professor Chandra Manning, one of the first to study the true intent of the soldiers fighting in the Civil War. She identified the Northern change of heart in Union letters, newspapers, and other writings. She also analyzed the letters, newspapers, and other published materials of the Confederates. Here is what she found. In fighting for slavery, the South was in fact fighting for much more. According to Manning, “losing to the Union was unthinkable, according to Confederate soldiers, because it would mean abolition, and abolition would destroy the southern social order.”17 She continues, “The loss of slavery would call white men’s right to rule over blacks into question, and once right to rule in any sphere was weakened, its legitimacy became suspect in every sphere. . . . Black slavery constantly reminded white men that in a society where most residents (African Americans, women, and children) were disenfranchised and subordinate to them, the independence that white men enjoyed as adult white males, and the ability to command . . . set them apart and identified them as men.”18

Southern Intent

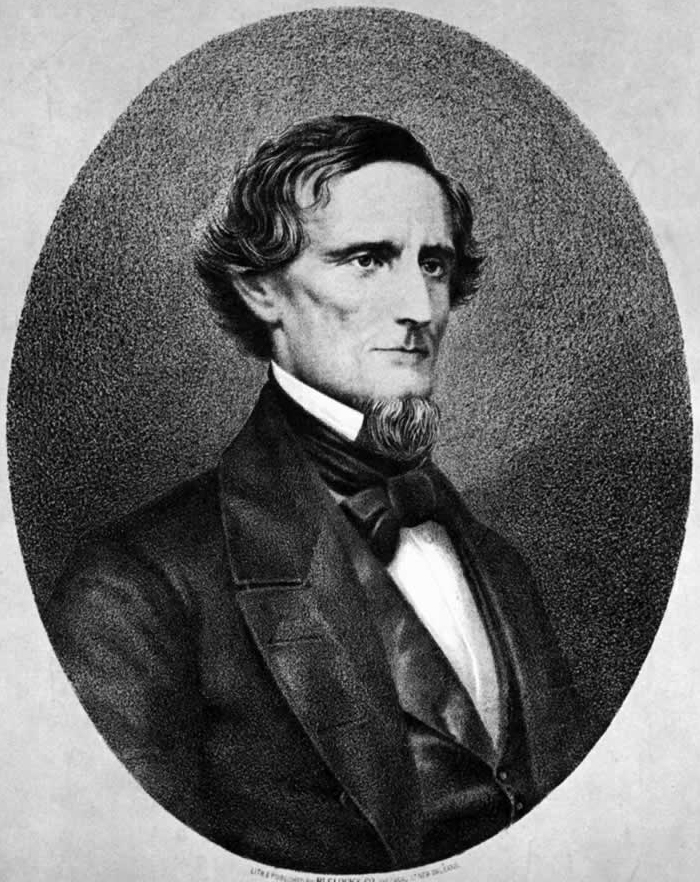

Why did the South fight? Many students of the war have theories they utilize today in order to push political agendas. We could listen to these theories, or we could simply ask the South why they did what they did. After all, they published their intent for all to see. For example, the president and vice president of the Confederacy spoke frequently about the need for Southern victory in order to preserve slavery; they called slavery the “great truth,” the “foundation,” and the “cornerstone” of their new government.10 Before the war, the would-be Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, “had frequently spoken to the United States Senate about the significance of slavery to the South and had threatened secession if what he perceived as Northern threats to the institution continued.”11 At the onset of the war, Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens stated that slavery was “the proper status of the negro in our civilization” and that the issue of slavery was “the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.”12

In South Carolina’s secession convention (the principal and most important secession convention), the delegates discussed their fears that Lincoln would allow “black Republicans” who were “hostile to slavery” to take positions of leadership in the government.13 They could not have been any clearer than they were in their own documents: the “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union” and their “Ordinance of Secession.” They printed it in black and white for all to read—their rebellion and secession were due to the “increasing hostility on the part of the non-slave-holding States to the Institution of Slavery.”14

The Confederate constitution made Southern intent even clearer. Southern leaders believed and declared, “Our new Government is founded . . . upon the great truth that the negro is not the equal of the white man. That slavery—subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.”15 During the war, Confederate President Jefferson Davis sought to make slaves of all black people in America, even free ones. In response to the Emancipation Proclamation, Davis ordered the following: “On or after February 22, 1863, all free negroes within the limits of the Southern Confederacy shall be placed on slave status, and be deemed to be chattels, they and their issue forever.” The order was to be executed even upon free black persons outside Confederate territory. Davis ordered that black people “taken in any of the States in which slavery does not now exist . . . shall be adjudged . . . to occupy the slave status.” Said Davis, the black race is “an inferior race, peaceful and contented laborers in their sphere.”16

Through the years and into the present day, Southern sympathizers have tried to make the argument that the South was not fighting for slavery, as evidenced by the fact that relatively few Confederates actually owned slaves. These Southern apologists fail to comprehend a slave society. White Southerners saw their slaves as property, just as farmers today view their farm equipment—their tractors, their horses, their cattle. If all the farm equipment and livestock just disappeared in any agricultural economy, everyone would be affected, though relatively few actually owned the equipment. Without these tools, the working folks (even those without the equipment) would have nothing to do, nowhere to go. The folks who bought and sold agricultural products (even those without farm equipment) would likewise find themselves jobless. They would all want and need the farm owner to preserve his tools and equipment. Likewise, Southerners (whether slave owners or not) wanted and needed their slavery. They understood what was at stake in this war. So should we.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

To further illustrate how this oppressive ideal readily flowed from the acceptance of slavery to the adoption of other ungodly principles, consider an exhaustive study done by political scholar Richard Bensel. Bensel dug deeply into the Confederacy’s handling of “property rights,” “control of the railroad,” “destruction of property,” and “confiscations.” He concluded that “the North had a less centralized government and was a much more open society than the South. . . . The Confederacy was far more government-centered and less market-oriented.” Agreeing with Dr. Bensel, renowned historians Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen have pointed out how the Confederacy nationalized enormous percentages of private industries. In the end, these two historians concluded that “The Confederacy reached levels of government involvement unmatched until the totalitarian states of the twentieth century.”19

And there is more. Under the Confederate constitution, the powers of the president were nearly unlimited, as no judicial check against the executive was put into place. The South’s constitution further supported censorship, even that killer of democracy. As best-selling author-historians Chris and Ted Stewart pointed out, “The Confederacy was not a clone of the United States with the simple addition of humans being viewed as property. It rejected the American Constitution. It rejected the Bill of Rights. It rejected the very foundation of democracy.”20

Lincoln was particularly concerned about the fact that the Confederacy’s founding documents erased any semblance of that American theme of “all men are created equal.” Lincoln pointed out that whereas the U.S. Constitution began with “We the People,” the Confederate equivalent began with “We, the deputies of the sovereign and independent States.”

“Why?” asked Lincoln. “Why this deliberate pressing out of view, the rights of men, and the authority of the people?”21

In the end, the war was fought over the existence of a social order. It was a fight to determine whether the promised land of America would or would not continue to maintain a system wherein one group dominated at will any other group it desired to rule. The North was right because (eventually) it began fighting against oppression of the human spirit, and oppression of the human spirit has been Satan’s plan from the beginning.

Yes, Satan’s plan. And he was winning before the war shook things up. The evidence of the adversary’s success is readily apparent in a reading of LDS history. History shows how Satan managed to take the principles of slavery and utilize those principles to attack the Latter-day Saints. The South liked to talk about “states’ rights.” This was the “noble cause” they claimed to be fighting for. Don’t be fooled. Yes, they were fighting for “states’ rights”—a state’s right to own a human being or burn down a Mormon temple or kill a prophet of God without any legal consequence. Remember the problem from the beginning: the states wanted the right to opt out of the Constitution, to deny the Bill of Rights to those they did not approve of (blacks, Mormons, and so on). They wanted the right to maintain that social order Professor Manning identified as the thing festering in their souls. This is what the North was fighting to change. This is what Joseph Smith sought to change in his America. It is why he screamed to the nation: “The States rights doctrine are what feed mobs. They are a dead carcass, a stink and they shall ascend up as a stink offering in the nose of the Almighty.”22

This is why Joseph sought an increase in federal authority—to quash the states’ rights doctrine that was responsible for denying blacks, Mormons, and other racial and religious minorities the God-given constitutional rights of liberty. It was the basis for Joseph’s political platform; it was the provision he claimed should be added to the Constitution. You will recall the important fact that this was the same solution for religious persecution that the “Father of the Constitution,” James Madison, demanded be amended into the Constitution (though he was rejected).

Once the North became converted to the covenant, it was blessed (like Joseph Smith and James Madison were) with this vision. That is why, again, the war became about bringing forth the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments—those tools that represented Joseph’s provision and eventually relieved the suffering in America. Once those amendments finally landed, states could no longer deny the Bill of Rights to America’s people; if they did, the national government would come to the rescue. This deterred most states from even trying to oppress racial and religious minorities as they had done before. Ultimately, those amendments provided the difference between burned temples and protected ones—between living, thriving prophets and murdered ones.

Yes, that evil social order derived from the demon slavery, and from the nineteenth century’s definition of the states’ rights doctrine, directly attacked the Latter-day Saints and the great gospel Restoration. We must understand this in order to understand Lincoln, the war, and the Restoration. Beyond the death and destruction of prophet and temple, I have more examples for you. Elder Parley Pratt, an Apostle, was murdered in the South some three years prior to the Civil War after converting a woman to the gospel. Her estranged husband disapproved of the conversion. And in accordance with this accepted and evil social order—which the North had only recently begun to reject and which the South was fighting to preserve—even a world in which the white male controls all in his “dominion,” the assailant and his friends caught up with Elder Pratt and killed him in cold blood, stabbing and shooting him in the back.24 Elder B. H. Roberts recorded the deaths of other LDS missionaries and members in this same general time period: Elder Joseph Standing, killed in Georgia; Elders John Gibbs, William Berry, and others, killed in Tennessee; and up to four hundred additional Saints killed in the border state of Missouri.25

“We have the highest reason to believe that the Almighty will not suffer slavery and the Gospel to go hand in hand. It cannot, it will not be.”

—John Jay, an inspired Founding Father23

The high number of Mormon casualties in Missouri certainly draws our attention to that state. For all intents and purposes, Missouri most certainly embodied the evil, antigospel political system the South was fighting to preserve. Though the state was technically north of the Mason-Dixon line, the Missouri Compromise of 1820 legalized the already active practice of slavery there, which had unleashed the oppressive culture that hurt the restored gospel. As one political scholar pointed out, “The spirit of mobocracy loosed against the Mormon people, that ignoble spectre of hate, became characteristic of the controversy over slavery and political power and was to bathe in blood . . . Missouri . . . and eventually culminate in Civil War.”26 One Missourian summed up the spirit in that state accurately when he announced that Mormons should not have civil rights, “no more than the negroes.”27 The Missouri mobocrats declared, “Mormonism, emancipation and abolitionism must be driven from the state.”28 This was the Southern cry. It was the opposite of God’s designs for America. It countered Lincoln’s new intention for the war. It directly challenged the American covenant.

Elder Roberts stated that these murders of the Saints in the South were a direct fulfillment of the Book of Mormon prophecy that the Restoration would come forth “in a day when the blood of saints shall cry unto the Lord” (Mormon 8:27).29 Indeed, the cries of the Saints would forever endure under the sociopolitical system that the South was fighting for—that the adversary was fighting for. This system above all else, which prevailed in the prehumbled, preconverted North and especially in the South, was drowning the Church. And with slavery on the rise, thus increasing the evil of all that slavery implied, hope grew dimmer. As Satan bought his armies and navies in the South to enforce these evil designs, hope grew dimmer still. You see why the North had to win this fight. You see why Lincoln arrived on the scene when he did.

But most important, you see why it was imperative that the people of the North were able to listen to the converted Lincoln and repent themselves, thus reactivating the American covenant. In the months after the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation (the first sign of national repentance), we begin to see the change of heart. It was right after the Proclamation went forth, during 1863, that the majority of those Professor Manning documents were produced—proof that the change in the North was taking effect. But the greatest proof that the North had finally crossed over to God’s side manifested itself that very summer—the summer of 1863. Two battles occurred that would determine the entire outcome of the war. These battles could have easily gone either way, and whichever side won them was going to win the entire war. They were the battles at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. The Union won both. Though they occurred on opposite sides of the country, both battles culminated on July 4! The North claimed it to be “divine intervention and [it] reawakened Union soldiers’ millennial understanding of the war.”30 Sgt. J. G. Nind summed up well such feelings in his own post-Gettysburg/Vicksburg reflections when he stated that now the “nation will be purified” and “God will accomplish his vast designs.”31

But nobody knew this more than Abraham Lincoln. You see, as the battle at Gettysburg was raging, the president found himself in what may have been the most powerful prayer of his life. In that moment, he made the covenant once again, ushering in the Union victory on his knees. (I will tell you more about that prayer in a later chapter.)

With the covenant at last reactivated, the Lord was able to bring in another miracle in the weeks and months after Gettysburg. It is a hidden gem in Civil War history—hidden because without Mormon scripture it means very little, and a gem because it manifests what this war was about and bears testimony of the Prophet Joseph.

It began on July 15, 1863 (days after Gettysburg), when Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Thanksgiving. In his proclamation, Lincoln encouraged Americans to pray and give thanks. In doing so he invoked the “Holy Spirit . . . to change the hearts of the insurgents.”32 And who were the insurgents? Obviously they included the Confederates and those of the proslavery movement in general. And certainly they should have especially included anyone who aligned themselves with such oppressive movements and had wielded such oppression over God’s Church and kingdom. If the many aforementioned gospel prophecies concerning the sociopolitical elevation of the Church were fulfilled through the Civil War, then we should certainly expect to see those enemies of the Church who caused its oppression to be affected, humbled, and positively changed by the war.

In the previous chapter, I pointed out a Joseph Smith prophecy (which he received while imprisoned in Liberty Jail) recorded in section 121 of the Doctrine and Covenants. This is the passage in which God promises to use the national punishment and scourge to “set his hand and seal to change the times and seasons” (verse 12). That prophecy was clear that God’s judgment and vexation upon the land would specifically seek out those who had “lift[ed] up the heel against mine anointed” and who had “[sworn] falsely against my servants, that they might bring them into bondage,” as well as those who had “driv[en], and murder[ed], and testif[ied] against them.” In other words, the punishment would fall upon the people who persecuted the Prophet and the Church. (In this same prophecy the Lord provides further evidence that this same generation would suffer the vexation by stating that in “not many years hence . . . they and their posterity shall be swept from under heaven.”) And this punishment and corrective action would fall upon these “children of disobedience,” even to the point that “their basket shall not be full,” and that “their houses and their barns shall perish” (D&C 121:11–24).

So, we must ask ourselves where these 1830s enemies of the Church found themselves during the 1860s war. We especially wonder about those in Jackson County, Missouri, who so horribly persecuted the Saints. Were these folks especially targeted in the war, as the prophecy indicates? The answer is chilling. The great American historian David McCullough pointed out that the Civil War in Missouri began some seven years before it began in the rest of the country: “It was a war of plunder, ambush and unceasing revenge. Nobody was safe. Defenseless towns were burned. . . . Neither then nor later did the rest of the country realize the extent of the horrors.”33 There is no doubt that Satan had set up camps in Missouri years earlier to stomp out any Mormon efforts to build Zion—certainly the adversary knew it was a promised land designated for Zion. Just because the Mormons left doesn’t mean the adversary did. As one eyewitness declared: “The Devil came to the border [state], liked it, and stayed awhile.”34

The Prophet Joseph, after all, was never shy about expressing his prophecy that Missouri would one day “witness scenes of blood and sorrow.”35 And indeed it did.

“The depopulation of Jackson . . . is thorough and complete. One may ride for hours without seeing a single inhabitant and deserted houses and farms are everywhere to be seen. The whole is a grand picture of desolation.”

—Excerpt from the St. Joseph Herald, October 186336

But there was one stunning and dramatic event that happened in Missouri within weeks of Lincoln’s appeal for corrective action to “change the hearts of the insurgents.” It was called General Order #11. It was a Union order to strike at the very heart of the evil brewing in Missouri. By August 1863, the Union army had recognized the mobocracy in Missouri that continually attacked those trying to support the Union and the eradication of slavery. It was this same mobocracy, perpetuated by the same groups of people, against freedom and liberty that had almost snuffed out the Saints years earlier. It was the same evil spirit of oppression introduced by the adversary to limit eternal progression and to impede the gospel plan—and it was this very evil that had therefore become a principal target of God’s vexation. This time the evil power was being specifically directed at antislavery supporters, and the Union army had seen enough.

And where exactly within Missouri did the Union armies see this spirit of mobocracy and destruction against the innocent? Where did the Union armies direct their attack under General Order #11? The answer is almost too fitting: Jackson County, along with a few other surrounding counties. General Order #11, issued on August 25, 1863, forced these Jackson County residents from their homes.37 The Doctrine and Covenants prophecy that “their houses and their barns shall perish” had been fulfilled to the letter.

General Order No. 11 (1863).

Evidence that this corrective action perhaps was successful is seen in General Order #20, issued months later. This order allowed all those who would take an oath of allegiance to the Union, and prove this allegiance, to return to their homes.38 In light of what we know the Union now stood for, Jackson County residents willing to accept this oath were, in a sense, entering the American covenant. They were promising to at last reject their self-serving ways and embrace the true constitutional principles of liberty and justice for all. I can’t help but wonder if, as they took their oaths and returned to their lands, they thought on “old Joe Smith.” I wonder if they remembered that he had told them this would happen. Either they could choose the right on their own, or God would vex them and humble them until they did so. Either way, I hope they did think on him; I hope they did realize that they had been caught and pinned in the frightening prophecies of that Mormon prophet whom—though he had sought to save them—they had sought tirelessly to destroy.

It was Lincoln’s policy throughout the war to allow captured rebels to take the “oath of allegiance” to the Union and the Constitution, thereby setting themselves free from Union bondage. Lincoln explained that such oaths embodied “the Christian principle of forgiveness on terms of repentance.”39 Though officials in his administration might have thought this a strange practice, it would not have been strange to one who had read the Book of Mormon. For Captain Moroni did the same.

With this understanding, the purpose of the Civil War becomes clearer than ever. Think about this: America had fallen so low that God literally picked up His Church and dropped it outside U.S. territory (where Utah is today). With the Saints safely tucked away, the Almighty then unleashed the prophesied scourge upon the land. As a result, Zion was being purged. As Brigham Young stated during the war, instead of suffering through the bloodshed and tears of fraternal conflict, the Latter-day Saints were “comfortab[ly] located in our peaceful dwellings in these silent, far off mountains and valleys. . . . We are greatly blessed, greatly favored and greatly exalted, while our enemies, who sought to destroy us, are being humbled.”40

Someday, with the purging complete, with the addition of Joseph’s constitutional provision (the amendments created in the wake of the war), and with righteousness restored in the land, the Mormons would be able to return to Zion, be a part of America and build their temples and grow their gospel. The promised land would not be defiled forever. God will not be mocked forever.

Yes, by 1863, the Civil War had indeed become an extension of that war in heaven. It had transformed into something nobody understood at the beginning of the conflict. God had kept His promise to Joseph, and now the Civil War could forevermore be described as “a fight . . . between God and the Devil—between heaven and hell!”41

Notes

^1. See Melissa Sanford, “Illinois Tells Mormons It Regrets Expulsion,” New York Times, April 8, 2004. President George W. Bush honored President Gordon B. Hinckley with the United States Medal of Freedom (see Michael K. Winder, Presidents and Prophets (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2007), 394.

^2. See Jessica Garrison and Joanna Lin, “Prop. 8 protesters target Mormon temple in Westwood,” Los Angeles Times, November 7, 2008, available at www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-protest7–2008nov07,0,3827549.story. For images of police in riot gear protecting the temple, see www.youtube.com, video number 0EtD0Bu9Bie.

^3. See “The Mormons,” produced and directed by Helen Whitney, PBS Special: American Experience, Frontline; airdate: April 30, 2007, program available at http://www.pbs.org/mormons/.

^4. In Richard Carwardine, Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 122.

^6. In an 1862 speech to the Emancipation League in Boston, accessed online at http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Frederick_Douglass.

^7. In Neil Kagan and Stephen G. Hyslop, Eyewitness to the Civil War (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2006), 23.

^8. I am aware of the Libertarian-based arguments on this point that the South was not really fighting for slavery, that slavery was going to die out on its own, that Lincoln’s reaction to Southern slavery actually destroyed freedom in the end, and so forth. These arguments discount the many evidences that tie the war and Lincoln to the Restoration.

^9. In Gordon Leidner, Lincoln on God and Country (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Books, 2000), 75.

^10. In Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen, A Patriot’s History of the United States (New York: Sentinel/Penguin Books, 2004), 350.

^12. In Scott Berg, Thirty-Eight Nooses (New York: Pantheon Books, 2012), 63.

^13. In Schweikart and Allen, A Patriot’s History, 298.

^14. “Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union and the Ordinance of Secession” (Charleston, SC: Evans and Cogswell, Printers to the Convention, 1860), 7–10.

^15. In Schweikart and Allen, A Patriot’s History, 302.

^17. Chandra Manning, What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 64.

^19. Schweikart and Allen, A Patriot’s History, 325–26; see also 301, 307.

^20. Chris Stewart and Ted Stewart, Seven Miracles That Saved America (Salt Lake City: Shadow Mountain, 2009), 163.

^21. In William Lee Miller, President Lincoln: The Duty of a Statesman (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 150.

^22. In Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 514.

^23. In Toby Mac and Michael Tait, Under God (Minneapolis: Bethany House, 2004), 287.

^24. See Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt, revised and enhanced edition, edited by Scot Facer Proctor and Maurine Jensen Proctor (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2007), 570–72.

^25. See B. H. Roberts, New Witnesses for God (U.S.A: Published by Lynn Pulsipher, 1986), 88–90; as originally published in Millennial Star, 50:44–47.

^26. Richard Vetterli, Mormonism, Americanism and Politics (Salt Lake City: Ensign Publishing Company, 1961), 81.

^27. In Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 357.

^28. In Vetterli, Mormonism, Americanism and Politics, 218.

^29. See Roberts, New Witnesses for God, 88–90; as originally published in Millennial Star, 50:44–47.

^30. Manning, What This Cruel War Was Over, 115.

^32. In Leidner, Lincoln on God and Country, 108.

^33. David McCullough, Truman (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 26–28.

^35. In Vetterli, Mormonism, Americanism and Politics, 297.

^36. From St. Joseph Herald, as reprinted in Deseret News, October 18, 1863; Kenneth Alford, ed., Civil War Saints (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2012), 102.

^37. General Order No. 11 (1863), available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Order_No._11_(1863).

^39. In Richard J. Ellis, To the Flag: The Unlikely History of the Pledge of Allegiance (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2005), 210–11.

^40. In Church History in the Fulness of Times, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2000), 382.