Chapter 14

![]()

The Gettysburg Prayer

At noon on October 18, 1863, Lincoln and Seward boarded the four-car train with its adornments of red, white, and blue bunting. They were off to visit Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, to help dedicate the new national cemetery, which had been created to receive the thousands of dead of that great battle. Lincoln had been asked to give an address. At least one reporter caught a glimpse of the duo boarding the train at Washington and felt inclined to report that, once again, Seward had chosen to go out in public wearing “an essentially bad hat.”1

It was a strange train ride. Lincoln was so pensive, it was as if he had entered some other realm. Some spiritual realm, perhaps. The feeling emanating from Lincoln and the North during this time was silent and somber, but somehow bright. Paradoxically, the light was connected to and couched in events surrounding the Battle of Gettysburg, which had shaken the land with immense death and destruction a little more than two months earlier. Notwithstanding the horror of it all, the battle had also proved to be a glorious Union victory and a sign that the American covenant had been activated—that God was on the side of the Union. All this was reflected in Lincoln as he sat quietly on the train. It was a somber brilliance, a sad triumph, a heavy victory. Indeed, it was a strange train ride.

As was the custom, the train made several stops for well-wishers along the route who were hoping to get a glimpse of the president, hoping to hear him expound upon the war, the country, anything. He would poke his head out and wave, but he did not have it in him to say anything. Ducking back into the train car, he turned to Seward and said, “Seward, you go out and repeat some of your ‘poetry’ to the people.”2

The same thing happened when they arrived at Gettysburg. Lincoln resided in the Wills residence while Seward stayed in a private home next door to him. Once word arrived that the president was in town, crowds flocked to the residence. Lincoln stepped out briefly, then dismissed the crowd using the classic Lincolnian technique—humor. He said he had to be careful not to say anything foolish and that the best way to do that was to say nothing at all. As the crowd laughed, he waved and ducked back into the house.

The unsatisfied crowd sought a consolation prize. They went next door and called out Seward’s name.3

Happy to help his best friend, Seward stood and spoke from his heart. He started with a joke: “I am now sixty years old,” he said. “I have been in public life, practically, forty years of that time, and yet this is the first time that any community so near the border of Maryland was found willing to listen to my voice.” They liked it. Then, trying to capture the truth of the moment, the truth that was congealing in Lincoln’s mind, Seward said: “I thank my God that this strife is going to end in the removal of [slavery]. . . . I thank my God for the hope that this is the last fratricidal war which will fall upon the country which is vouchsafed to us by Heaven.”4

The battlefield at Gettysburg.

After the crowd dispersed, Lincoln snuck over to Seward’s residence with his draft documents for the address he was to give the following day. They spent an hour discussing. Seward later admitted that he could do very little to improve the address. Looking back, perhaps the most important thing that came out of their little discussion was the formalization of a new policy that affects all Americans even today. Lincoln granted Seward permission to institutionalize the celebration of Thanksgiving—that’s Thanksgiving to God, for those of us (too many of us) who have forgotten the meaning of that holiday. Fittingly, in Gettysburg they made it the national holiday it is today.5

Early the next morning, Lincoln and Seward got up and toured the battlefield in a carriage. They could not believe their eyes. The terrifying evidence of bloody war lay all about them. Decaying horse corpses were strung about the landscape. Knapsacks, canteens, soldiers’ coats, and shoes were scattered all over the rolling hills—their owners gone forever, unable to reclaim their once precious items.6 Near the cemetery they viewed seemingly innumerable coffins stacked upon each other waiting for interment. Lincoln was overcome as he walked through these death fields. One witness heard him whisper, “I gave myself to God, and now I can say that I do love Jesus.”7

Jesus. According to our scripture, America is a “choice land” to be “free from bondage” as long as the people adhere to the “God of the land, who is Jesus Christ” (Ether 2:12). He is the God of this land and the God of the covenant. Perhaps this was why Lincoln had shown such deep emotion since boarding the train for Gettysburg. The nation was in the moment of change, the moment of conversion to that covenant. This battle had led them there. Gettysburg was the pivotal point. As Edward Everett would say later that day during his keynote address at the Gettysburg ceremony, this battle was going to determine whether America “should live, a glory and a light to all coming time, or should expire like the meteor of a moment.”8 You see, Confederate General Robert E. Lee had come to Gettysburg to score a Southern victory in Northern territory—something he had not yet been able to do. If he had been successful, nothing would have stopped his march into the U.S. capital. The war would have been over. The only thing standing in Lee’s way at that moment was the covenant on this land—the God of this land.

But had America done enough at that point to reactivate the covenant in order to utilize its power at this do-or-die battle? Had the humbling effects of war brought enough of its people to their knees? Had they felt the mighty change of heart experienced by their president? Would God intervene on the battlefield in favor of the Northern cause? These were the important questions during those days and hours leading up to the battle at Gettysburg. And the world was about to discover the answers. But Lincoln was prepared to find out first.

As the battle began to rage in Gettysburg, Lincoln dropped to his knees. He had come to believe in the covenant, for he had seen its effects. On behalf of the nation, he would invoke it once again. He would “pray in” the victory. And he did! The North won. After the battle ended, and Lee was running back to the South, Lincoln visited Union General Dan Sickles in a military hospital. The general had been severely wounded at the battle and was fighting for his life. Lincoln felt impressed to share his prayer experience with the bedridden general. According to Sickles and General James Rusling, who was also present, Lincoln recounted the following:

In the pinch of the campaign up there [at Gettysburg] when everybody seemed panic stricken and nobody could tell what was going to happen, oppressed by the gravity of our affairs, I went to my room one day and locked the door and got down on my knees before Almighty God and prayed to Him mightily for victory at Gettysburg. I told Him that this war was His war, and our cause His cause. . . . And I then and there made a solemn vow to Almighty God, that if He would stand by our boys at Gettysburg, I would stand by Him. And He did stand by your boys, and I will stand by Him. . . . Never before had I prayed with so much earnestness. I wish I could repeat my prayer. I felt I must put all my trust in Almighty God. He gave our people the best country ever given to man. He alone could save it from destruction. I had tried my best to do my duty and found myself unequal to the task. The burden was more than I could bear. I asked Him to help us and give us victory now. . . . And after that, I don’t know how it was, and I cannot explain it, but soon a sweet comfort crept into my soul. The feeling came that God had taken the whole business into His own hands and that things would go all right at Gettysburg. And that is why I had no fears about you.9

As Lincoln stood to leave General Sickles’s bedside, the general related that “Mr. Lincoln took my hand in his and said with tenderness, ‘Sickles, I have been told, as you have been told perhaps, that your condition is serious. I am in a prophetic mood today. You will get well.’” And he most certainly did.10

I can’t help but share one more tidbit, one that connects this prayer experience to the Book of Mormon. Perhaps it means nothing, but I must share it with you in case it does. As I ponder Lincoln’s prayer, I can’t help but see that wonderful military character in the Book of Mormon named Helaman. There is something about Helaman that reminds me of Lincoln and his Gettysburg experience. Perhaps it was Lincoln’s continued reference to the Gettysburg soldiers as “your boys.” Helaman, you will recall, repeatedly called his young stripling warriors “my two thousand sons,” “those sons of mine,” “my little sons” (Alma 56:10, 17, 30). The same tenderness was there. Or perhaps it was the heavenly assurance Lincoln received prior to the Gettysburg victory—God told him the North would win. Similarly, God told Helaman that his sons would see victory in their battle: “Yea, and it came to pass that the Lord our God did visit us with assurances that he would deliver us; yea, insomuch that he did speak peace to our souls . . . that we should hope for our deliverance in him” (Alma 58:11). Lincoln’s cause and covenant and American land were, of course, Helaman’s same cause, same covenant, and same American land. “[We] were fixed with a determination to conquer our enemies, and to maintain our lands . . . and the cause of our liberty” (Alma 58:12).

But the connections continue—and this part stunned me. Interestingly, it was my eleven-year-old son, Jimmy, who pointed this startling fact out to me during a family reading session of the fifty-sixth chapter of Alma.

Of all my children, Jimmy reminds me of how I imagine young Willie Lincoln to have been—thoughtful, analytic, sometimes too smart for his age, and always ready to deliver a good prank. Willie was Jimmy’s age when he died, which somehow helps me to imagine some of the pain Lincoln felt. Months before this insight from my Jimmy, I had taken him by himself on a special trip to Gettysburg. As we walked the battlefield together, I told him what had happened there and what Lincoln had been doing back at home to usher in the victory. It was one of the most memorable experiences of my life.

Anyway, the point I want to make—the insight Jimmy gave me—was the fact that Helaman provided the exact day of the first battle his sons were engaged in: “the third day of the seventh month” (Alma 56:42). Now, I do not know how the Nephite calendar worked, but I do know the book was written for us. And I do know that the third day of the seventh month to us is, as Jimmy pointed out, July 3. “Dad,” Jimmy interrupted our reading session excitedly, “July 3 is the very day the Battle of Gettysburg raged!”

As you might imagine, when I visited the Library of Congress to review the Lincoln Book of Mormon, I made sure not to skip the part where Helaman tells this story. In that first edition copy, the entire Helaman epistle, in which he writes about his sons and their battles (everything I just quoted), is contained in one single chapter. (In later editions, the Church divided the book into additional, smaller chapters.) But to Lincoln, the whole Helaman army experience—the covenant, the spiritual assurances, the battles, and everything—was all contained in one single chapter. I kid you not when I tell you this: of the relatively few dog-eared pages in that Lincoln Book of Mormon, this Helaman chapter—the very first page of it!—was one of them. Somebody reading this copy many years ago felt inclined to mark it well.11

But I digress. Let’s go back to Lincoln on the battlefield. . . .

As I think about that scene of Lincoln touring the battlefield, these are the thoughts that fill my mind—covenant, repentance, choice land, the Christ. I wonder if these things were brimming in Lincoln’s soul as he walked over that sacred ground where so many had made the ultimate sacrifice for this righteous cause. At last, with this victory, Lincoln could see the silver lining amidst the dark clouds of war. As I mentioned earlier, the news of Union victory at Gettysburg was accompanied by news of another Union victory in the western theater—the battle at Vicksburg. Both victories culminated on July 4, which the nation took as a sign that God had blessed their arms and that He was on their side. In hindsight, we can see through the many Northern writings and publications leading up to the battle (which writings and publications I discussed in an earlier chapter) that the North had become sufficiently repentant. This is what activated the covenant blessings. The victories confirmed the truth of it. One Union officer spoke for the rest after the Gettysburg-Vicksburg victories when he said that now the “nation will be purified” and “God will accomplish his vast designs.”12

This was the message Lincoln was about to give that very day in his Gettysburg Address.

Lincoln and Seward left the battlefield together, returned to their houses to change their clothes, then joined the procession to the cemetery. The president and Seward were ushered to the raised platform and took their seats right next to each other. They looked upon the crowd—about 25,000 people had gathered.13 Perhaps, as they looked out among the thousands of faces, they pondered the sickening fact that this enormous crowd was equal to only half of the number of the Gettysburg dead.

The chaplain stood to open the ceremony. He prayed, “Oh God, our Father, for the sake of Thy Son, our Saviour, inspire us with Thy Spirit.” His prayer continued on and recognized the war as a fight about “Liberty, Religion, and God.” Perhaps Seward and the others on the stand noticed that many in the crowd were looking at Lincoln during the prayer, for Lincoln had, once again, become flooded with emotion, wiping tears from his face.14

At last it was his turn to speak. And when he did, he kept the Spirit alive in Gettysburg.

Fourscore and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

We should not take for granted these familiar lines. Listen to what Lincoln is saying. Consider the gospel implications of his message. God gave us this covenant land—the only land of liberty on the face of the planet at that time, the only land capable of supporting something like the Restoration. If the North failed now, the rest of the world would be able to maintain their long-held belief that self-government and the pure liberty it provides is not possible. Indeed, it was a test to see if our nation or any nation so conceived . . . can long endure. If it could, democracy would be emulated and would grow, and the gospel would find safe haven throughout the world. If not, Satan would chalk up a victory against righteousness.

Lincoln delivers his Gettysburg Address.

As was said by scholar Gabor Boritt (one of the world’s foremost experts on Gettysburg), the Gettysburg Address “reached beyond the American problem of slavery to the global problem of liberal democracy.”15 Indeed, Lincoln often said the same thing—that this civil war is “an important crisis which involves, in my judgment, not only the civil and religious liberties of our own dear land, but in a large degree the civil and religious liberties of mankind in many countries and through many ages.”16 On another occasion, he declared that in this war “constitutional government is at stake. This is a fundamental idea, going down about as deep as any thing.”17

No wonder Lincoln in general, and the Gettysburg Address in particular, have been quoted by freedom fighters the world over—from Gandhi in India, to revolutionaries for democracy in Latin America, to Mandela in South Africa, and to independence-loving student movements in Hungary (1956), Iran (1979), and China (1989).18 No wonder Lincoln called America “the last best hope of earth.”19

Make no mistake, the future cause of the restored gospel hung in the balance of the Civil War.

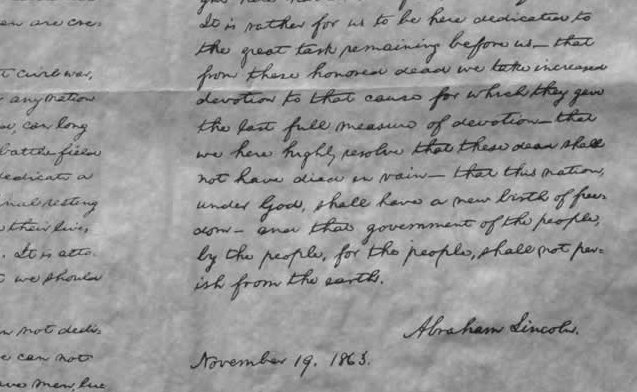

Handwritten draft of the Gettysburg Address.

Which makes the concluding words of Lincoln’s address all the more potent:

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.20

This was the call to the covenant! We must now take increased devotion to that cause! We must continue forward! We must not give up on that God-given liberty that leads to the salvation of mankind!

Almost in the instant it was given, reporters telegraphed the words of the Gettysburg Address throughout the North. Those millions of now-converted American souls read and understood. They committed to rally around Lincoln and accept his call. As Boritt wrote, the nation devoured Lincoln’s words, thus “immersing [themselves] in one fastening ritual, creating community.”21 It was a covenant community.

One minister from Gettysburg confirmed the national sentiment: “The deadly war that is now waging, is, on the one hand, the price we are paying for past and present complicity with iniquity; on the other, it is the cost of . . . the realization of the grand idea enunciated in the Declaration of Independence.” The North must accept Lincoln’s call to fight and destroy that “mortal antagonist of Democratic Institutions,” and usher in “a higher, purer, nobler national life and character.” And so, concluded the Gettysburg minister, echoing Lincoln’s call to endure this awful crisis: “God forbid” the war should stop “short of this glorious end.”22

In the moment Lincoln finished his short and powerful address, he stood silently on the stage, likely wondering what response he would receive from the crowd. Seward, sitting behind him and also looking out over the people, must have wondered the same thing. The people also stood or sat there silently for a moment, their eyes fixed on their president, their minds and hearts still absorbing the powerful message. Then something happened that many would never forget. Eyes began to focus in on a young army captain in the crowd. In many ways, he represented all of America—the whole nation. For, though he was wounded (he was missing an arm), just as the whole nation was wounded, he stood tall and determined and full of God’s light. Overcome with emotion like the rest, the soldier buried his weeping and shaking face into his good arm and cried aloud, “God Almighty bless Abraham Lincoln,” to which it seemed the crowd responded solemnly, “Amen.”23

Notes

^1. Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012), 384.

^2. John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln’s Right Hand (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 223.

^3. See Stahr, Seward, 384–85.

^4. Taylor, William Henry Seward, 223–24.

^7. In Richard Carwardine, Lincoln: A Life of Purpose and Power (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 320. Lincoln’s quotation here, though quoted by many, has never been fully substantiated.

^8. Gabor Boritt, The Gettysburg Gospel: The Lincoln Speech That Nobody Knows (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 129.

^9. In Newt Gingrich, Rediscovering God in America (Nashville, TN: Integrity Publishers, 2006), 54; see also Chris Stewart and Ted Stewart, Seven Miracles That Saved America (Salt Lake City: Shadow Mountain, 2009), 190–91.

^10. In Don E. Fehrenbacher and Virginia Fehrenbacher, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), 406.

^11. These observations were made by the author as he studied that first edition copy of the Book of Mormon in the Library of Congress.

^12. In Chandra Manning, What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 157.

^14. In Boritt, Gettysburg Gospel, 97.

^16. In Roy P. Basler et al., eds., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 9 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 5:212; emphasis added.

^17. In William Lee Miller, President Lincoln: The Duty of a Statesman (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008), 151.

^18. See Boritt, Gettysburg Gospel, 202.

^19. In Carwardine, Lincoln, 217.

^20. In William J. Bennett, The Spirit of America (New York: Touchstone, 1997), 368.