12

Sabbats

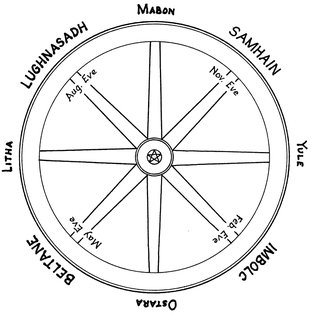

The main celebrations of the Witch year are known as the Sabbats. Gail Duff (Seasons of the Witch, 2003) suggests that the word Sabbat comes from the Greek sabatu, meaning “to rest.” There are eight of these celebrations. The four major ones—also known as the “cross-quarter days”—are Samhain (pronounced Sow-in), Imbolc (Im-’olk), Beltane, and Lughnasadh (Loo-n’suh). They fall on November Eve, February Eve, May Eve, and August Eve respectively. The four minor celebrations fall on the Summer Solstice (also known as Litha), the Winter Solstice (Yule), the Spring Equinox (Ostara), and the Autumn Equinox (Mabon). The date for the Summer Solstice is approximately June 21 (it will change slightly each year, dependent upon the calendar). The Winter Solstice is approximately December 21, the Spring Equinox approximately March 21, and the Autumnal Equinox approximately September 21. The solstices mark the longest day/shortest night (Summer) and the shortest day/longest night (Winter), while the equinoxes mark the time when the day and night are of equal length. The eight festivals are roughly six weeks apart. It used to be that the celebrations of these Sabbats, by the early pagan population, went on for anywhere from three days and nights to seven days and nights, culminating on the dates mentioned above. Today, most Witches just celebrate on the one day.

The Wheel of the Witches’ Year

To early humankind the year was first divided into two parts: summer and winter. Although it was possible to grow food in the summer, it was necessary to hunt for animals for food in the winter. The God, as a god of hunting, predominated during the winter months and the Goddess, as a goddess of fertility for the crops, predominated in the summer. The changes occurred at Samhain (November Eve) and Beltane (May Eve). Later in the development of humankind, it was learned how to store the crops from the summer to last through the winter, so success in hunting became less important and the Goddess predominated throughout the whole year, though with the God by her side.

To mark the halfway point through each of the halves of the year, Imbolc (February Eve) and Lughnasadh (August Eve) came into being. The word Imbolc means “in milk” and is associated with the lactating of sheep and other domestic animals at that time. The word Lughnasadh means “married to Lugh (the sun god).” Like most of the festival names, these are of Celtic origin. The equinox and solstice celebrations tie in with the progress of the sun through the year, but the four major (and oldest) festivals are more agricultural in their associations, tying in to the land, crops, and animals.

As a Solitary Witch, feel free to celebrate the Sabbats in any way that appeals to you. You can feast, sing, dance, act out a solitary play (very traditional for all of the Sabbats), compose a special poem or song, plant a tree, or whatever. Many Witches tie in their celebration with the theme of the time of year, looking to the old myths and folklore for inspiration; for example, at Yule the Goddess gives birth to a son, who is the God and the sun. At Imbolc the Goddess is recovering while the young God is growing and learning of his power. At Ostara the God grows to maturity while the Goddess awakes from her sleep. Beltane marks the God’s full emergence into manhood and his desire for the Goddess, who becomes pregnant by him. At midsummer (Litha), the fertility of the Goddess is at its peak. Lughnasadh sees the God losing his power and starting toward death, while the Goddess feels the child within her, who will become the new God. At Mabon the God prepares to depart for the darkness of death and what lies beyond, while the Goddess acknowledges the weakening of the sun. Samhain shows the Goddess preparing for the birth she will give at Yule and the God says his farewell. For full, detailed explanations, stories, and myths associated with each of the Sabbats, I highly recommend Eight Sabbats for Witches by Janet and Stewart Farrar (Hale, London 1981).

The Sabbat was a time for celebration, therefore magic was not usually done at these times (unless there was some emergency—for example, healing was needed), so save this for the Esbats. However, divination was often a part of the rites; these turning points seeming to be an appropriate time to look and see what the future might hold. Below I give suggested rituals for each of the Sabbats. Work with them as they are or use them as inspiration for your own versions. You do not have to do the same thing year after year either; it is fine to compose new rituals each year or whenever you feel the need or desire. I’ll say again, the Sabbats were a time for celebration, so use them to celebrate not only the turning of the wheel of the year, but also life itself and what it means to you.

In Natural Home magazine (May/June 2003), Carol Venolia wrote an article on celebrating the seasons. In it she told how ritualist L. Bachu celebrated Samhain by setting a table with candles and pictures of loved ones, even going to the trouble of laying out a meal of apples, chocolate, whole-grain bread, and wine for them. David Rousseau, a Canadian architect, said that he would sit with friends around a fire at the winter solstice, tossing into the fire pieces of paper on which had been written anything they considered “bad news.” Each would first read their “bad news” then everyone would chant “Bad news!” as it was thrown into the fire. This is very similar to the ritual we give here (see below). Another architect, Marcia Mikesh, marked each equinox and solstice by eating only foods she had grown on her own land. There are many such simple rituals that can be made up and performed to draw us closer to nature and to an awareness of life. Make up some of your own and work them into the following rituals.

Samhain

Samhain is the turning point of the year; it is the Celtic New Year’s Eve, sometimes referred to as the Feast of the Dead, Feast of Apples, or Ancestor Night. When the new religion, Christianity, adopted this festival—as was done with so many of the old pagan celebrations—they aligned it with their own festival known as All Saints, All Souls, or All Hallows. The eve of it, which is when pagans and Witches would actually do their celebrating, was All Hallow’s Evening. This became shortened to Hallow’s Eve or Hallowe’en. Witches call it Ancestor Night because this is the time—between the end of the old year and the start of the new—when it is felt that the veil between this world and the next is very thin and therefore it’s much easier to contact the spirits of your dead loved ones. Indeed, this was how the jack-o’-lantern originated. When traveling to the Sabbat site, Witches would believe that the spirits of their dead traveled with them. To light their way, the Witches would carry lanterns, often made out of hollowed-out turnips or pumpkins with a candle inside. It was then only a short step to carving a face on such a lantern so that it could better represent the departed spirit traveling along.

The focus of Samhain is honoring the dead, along with winter preparations and divination. It is a time for getting rid of the things you don’t want to have to take with you through the winter. In the old days, even the herds and flocks would be thinned, so there would be meat on hand through the winter and so there wouldn’t be unnecessarily large numbers of animals to have to feed in the hard months to come. So keep this culling of unnecessary things in your mind when you compose your own ritual. Take a piece of paper and write on it all the things you would like to clear out of your life. You can list habits you would like to break, projects you want to finish, and medical condition(s) you want to alleviate. This is also a time for divination—for peering through the crack in time—thanks to the agencies of the crone aspect of the Goddess.

* * *

The circle and the altar are decorated with things appropriate to the season: small pumpkins, branches, flowers (possibly marigolds and/or chrysanthemums), nuts, apples or other fruit, and so on. Candles, both on the altar and around the circle, can be white or orange. In addition to the usual altar tools, have a small dish (a miniature cauldron would be ideal) and the piece of paper listing those things you want to get rid of. Also on the altar have photos of any ancestors, now dead, who are special to you. If you wish, you may have tarot cards or a crystal ball (depending upon your own favorite form of divination) sitting on the ground beside the altar.

The Opening the Circle ritual is done. If it is at, or close to, the full moon or the new moon then the appropriate rite is performed. After that, you return to the altar and ring the bell seven times. Raise your wand high and say:

“Hail to the Mighty Ones; the Lord and the Lady; Herne and Epona! I stand today at the Crack of Time; at the division between the old year and the new. Through this crack may pass those I have known and loved in the past, who have gone on to the Summerland. I greet their return and share my love with them as they share with me. I know that this Samhain time is special for such meeting, though it is not unique. At this time, I also give thanks to the crone aspect of the Lady and her gifts of future sight. To the Lord I pledge my love and support as he embarks upon his journey through the dark half of the year.”

Lower your wand and take up the photos of your deceased loved ones. Spend some time thinking of them. You can speak to them as though they are present (which they are and you may even actually see them). Give them your love and let them know they are not forgotten. Ring the bell three times.

Now turn to your wish to rid yourself of unnecessary “baggage.” Take up the list you have made and study it. As you read each item, think about it and realize how much happier you are going to be without it. Know that, with the act you are about to perform, you will free yourself of these problems. Now take the paper, light it from the altar candle, and hold it over the dish. Let it burn, its ashes falling into the dish. As it burns, picture the items listed on the paper falling away from you, leaving you and your body. Feel the weight of these things lifting from your shoulders. As the last of the paper burns, say “Thank You” to the gods. Ring the bell three times.

Now is a good time to do some divination, if you wish. Whatever is your particular favorite should be indulged in. Look to the future and see what you can reveal; see what the coming year has in store for you in the way of opportunities. Remember that nothing is set in stone (see chapter 15, Divination), and that what you may see is only an indication of how things may go, depending upon many different factors.

When you have finished, ring the bell three times. Now, if you wish, you may sing and/or dance about the circle. Enjoy the feeling of change. End by sitting (or kneeling or standing) and, in your own words, thank the gods for all they have given you in the past year. Feel free to ask for what you would like in the coming year.

Do the Cakes and Wine rite and end with Closing the Circle.

Winter/Yule

Yule (from the Norse Iul, meaning “wheel”) has the shortest day and longest night of the year. It is the turning point in the dark half of the year, going from the waxing to the waning year. Yule is a time to celebrate the return of the sun and the rebirth of the God. It is a time to think about your hopes for the coming year, and your plans and aspirations.

* * *

The circle and the altar are decorated with things appropriate to the season: ivy, mistletoe, holly, pine boughs, bay, and rosemary. Candles, both on the altar and around the circle, can be green, red, or purple. In addition to the usual altar tools, have an extra (unlit) red candle (see note below).

The Opening the Circle ritual is done. If it is at, or close to, the full moon or the new moon then the appropriate rite is performed. After that, return to the altar and ring the bell seven times. Raise your wand high and say:

“Hail to the Mighty Ones; the Lord and the Lady; Herne and Epona! The Sun Lord dies yet also he lives! At this time, when the Sun is at its lowest point, I send forth my energies to the Lord to bring him life and to send him on his way toward our Lady, who waits at the entrance to springtime. This is the time for the Goddess to give birth to her Son-Lover, destined to imbue her and thus return the light. Hail, Lady! Queen of the Heavens and of the Night. Bring to us the Child of Promise!”

Light the extra red candle from the altar candle. Sit, kneel, or stand and meditate on the passage of the God through the dark half of the year. See him at this turning point, reborn and starting on the waxing passage through to the spring. Give thanks to the gods for what you have and for the hopes and promises that lie before you. When you have finished, ring the bell three times.

Now, if you wish, you may sing and/or dance about the circle. Enjoy the feeling of change. End by sitting (or kneeling or standing) and, in your own words, thank the gods for all they have given you in the past.

Do the Cakes and Wine rite and end with Closing the Circle.

[Note: If you are lucky enough to be able to have your circle outdoors, then instead of the extra candle on the altar, have a small fire ready for lighting in the north quarter of the circle and ignite that rather than lighting the extra candle. In dancing around the circle, you can jump over the fire as you circumambulate.]

Imbolc

Imbolc, or Oimelc, is basically an early spring festival. It is a time to prepare for the new season; it is a time of new opportunities. This was the occasion for the old Feast of Torches. At sunset people would light lamps or candles in every room of the house, honoring the sun’s rebirth. In some Scandinavian countries, a maiden is chosen to wear a crown made of thirteen candles. Many Wiccan celebrations focus on the goddess Bride (pronounced “breed”) for, despite falling within the “dark half” of the year, Imbolc is actually a very Goddess-oriented Sabbat. Bride is associated with poetry, so this would be a good Sabbat at which to read (or even to do the actual writing in the circle and then read) a poem.

The last sheaf of the previous year’s harvested wheat traditionally is kept to be used as the seed for the new harvest. From this sheaf, a doll was often made, known variously as a corn dolly, harvest mother, or sheaf mother. In Gaelic it was the brídeóg, or “biddy.” Quite often this doll would be dressed in women’s clothing and laid in a small bed known as the Bride bed. Symbolic corn dollies were also made, weaving and braiding the cornstalks into traditional patterns, forming squares, crosses, and similar. If you feel so inclined, a good project would be to make a corn dolly.

The circle and the altar are decorated with things appropriate to the season: small evergreen branches, bay sprigs, holly, nuts, fruit, and so on. Candles, both on the altar and around the circle, can be white or yellow. In addition to the usual altar tools, have an extra white (unlit) candle on the altar (see Note). On the ground beside the altar have a corn dolly or (if you haven’t made one) a Priapic wand (see chapter 5, Tools). You may also have a crystal ball or deck of tarot cards there.

The Opening the Circle ritual is done. If it is at, or close to, the full moon or the new moon then the appropriate rite is performed. After that, you return to the altar and ring the bell seven times. Raise your wand high and say:

“Hail to the Mighty Ones; the Lord and the Lady; Herne and Epona! Winter draws to its end and releases its hold on the land. Torches blaze and light shines forth to welcome the progress of our God. As winter goes out of one door, so spring comes in at the next. Farewell to death and bright greetings to life; farewell to the old and greetings to the new. The wheel turns and, as it does, we move ever forward.”

Ring the bell three times. Light the white candle from the altar candle, saying:

“And welcome anew to the young God, who grows and embraces us all.”

If you have a corn doll then place it on the altar (if not, then the phallic wand. If you have both, lay the phallic wand on top of the corn doll. If you have neither, use your regular wand) with the words:

“Welcome, Lady Bride; Lady of Light; Three-in-One Goddess of us all. Young Goddess of New Beginnings.”

If you have written a poem, then recite it now. (If you feel inspired, write one now and then recite it.) When you have finished, ring the bell three times.

If you wish, you may now sing and/or dance about the circle. End by sitting (or kneeling or standing) and, in your own words, thank the gods for all they have given you in the past. If you wish to do some divination, now would be a good time to do it.

Do the Cakes and Wine rite and end with Closing the Circle.

[Note: If you are lucky enough to be able to have your circle outdoors, then instead of the extra candle on the altar, have a small fire ready for lighting in the north quarter of the circle and ignite that rather than lighting the extra candle. In dancing around the circle, you can jump over the fire as you circumambulate.]

Spring/Ostara

Spring is a sign that winter is truly over. Light is conquering darkness, though here they are of equal length. Ostara (also spelled Œstra, Œstara, Eostre, and Eostra) was the Anglo-Saxon goddess of spring. When the Christians borrowed this part of paganism they renamed it Easter. The Easter egg and Easter rabbit come from the fact that Ostara was a fertility goddess, with eggs and rabbits (or hares) symbols of fertility. Her name was probably a variant of Astarte, Ishtar, and Aset. Another symbol of the spring goddess is the snake, the shedding of whose skin is a strong symbol of rebirth and an ancient symbol of new life coming out of old.

The circle and the altar are decorated with things appropriate to the season: evergreen branches, wild flowers, pussy willow, daffodils, primroses, celandines, and so on. Candles, both on the altar and around the circle, can be white, green, or orange. In addition to the usual altar tools, have a small bowl filled with earth and a number of seeds of some kind. The Opening the Circle ritual is done. If it is at, or close to, the full moon or the new moon then the appropriate rite is performed. After that, you return to the altar and ring the bell seven times. Raise your wand high and say:

“Hail to the Mighty Ones; the Lord and the Lady; Herne and Epona! Welcome to Herne and Epona and welcome to the spring. Now is the time to sow the seeds of my future. To know that the seed is in the ground, and will be developing and growing through the coming weeks and months, fills me with joy in the knowledge that my hopes and dreams will eventually be bursting forth in full bloom. Lord and Lady, receive this seed I offer and nurture it, bringing it to its full potential. So Mote It Be.”

Sit, kneel, or stand and contemplate for a few moments those things that you would like to see come to fruition in the near future. Spend some time deciding what is most important and how that development of what you desire might affect others around you. Be sure that nothing you bring about for yourself will have a negative impact on anyone else. Then take the bowl of earth and, with the tip of your wand, make a small space in the center, pushing down to make a hole. Then take the seeds you have and hold them in your hands, cupped between the palms. Concentrate your energies into the seeds. Ask (silently or out loud, in your own words) the gods to bless them and to see that they prosper. Then drop the seeds into the hole and, with the fingers of your dominant hand, close the earth over them. Hold up the bowl over the altar and say:

“Here are the seeds I have planted in the womb of the Lady. Let them develop and grow to full maturity. May Herne and Epona join with me in watching over them and guiding them to prosper, as my own plans may prosper. So Mote It Be.”

Ring the bell three times. Now, if you wish, you may sing and/or dance about the circle. End by sitting (or kneeling or standing) and, in your own words, thank the gods for all they have given you in the past.

Do the Cakes and Wine rite and end with Closing the Circle.

Beltane

Beltane (spelled variously Bealtaine, Bhealtyainn, Bealtuinn, and similar) is opposite Samhain, as one of the main turning points of the year. The Irish Gaelic pronunciation is “b’yol-tinnuh” but most Witches just pronounce it as written: “Bell-tain.” The festival is probably named after the Celtic sun god Bel, known as “the Bright One.” As the main shift of season in the Celtic calendar, it is especially at this time that the focus turns from the God to the Goddess, who will be predominant through the summer months. Traditionally, two bale fires were lit and cattle and other livestock were driven through between the fires, to consecrate them, protect them from disease, and to give them the sun god’s blessing. Couples would often take hands and, together, jump over the fires for fertility and good luck.

This was the time when the maypole was erected. The themes of the festival were sexual love, fertility, birth, and creativity, the maypole being a phallic symbol. It was a time known for joy and festivity. Phillip Stubbs, the Puritan, said of it:

Against May, Whitsunday, or other time, olde men and wives, run gadding over-night to the woods, groves, hills and mountains, where they spend all night in pleasant pastimes; and in the morning they return, bringing with them birch and branches of trees, to deck their assemblies withal.... But the chiefest jewel they bring from thence is their May-Pole, which they have bring home with great veneration.... They have twentie or fortie yoke of oxen, every oxe having a sweet nose-gay of flowers placed on the tip of his hornes, and these oxen drawe home this May-Pole (this stinking Ydol, rather), which is covered all over with floures and hearbs, bound round about with strings, from the top to the bottome, and sometime painted with variable coulours, with two or three hundred men, women and children following it with great devotion. And this being reared up . . . then fall they to daunce about it, like as the heathen people did at the dedication of the Idols, wereof this is a perfect pattern, or rather the thing itself. I have heard it credibly reported (and that viva voce) by men of great gravitie and reputation, that of forty, threescore, or a hundred maides going to the wood over-night, there have scarcely the third of them returned home againe undefiled. (Anatomie of Abuses, 1583)

This is somewhat echoed by Rudyard Kipling’s words (which have been adopted by many modern Wiccans as their “May Eve Chant ”):

Oh, do not tell the priests of our rites

For they would call it sin;

But we will be in the woods all night

A-conjurin’ summer in!

For they would call it sin;

But we will be in the woods all night

A-conjurin’ summer in!

Janet and Stewart Farrar, in Eight Sabbats for Witches, mention that “Bealtaine for ordinary people was a festival of unashamed human sexuality and fertility. Maypole, nuts, and ‘the gown of green’ were frank symbols of penis, testicles, and the covering of a woman by a man. Dancing around the maypole, hunting for nuts in the woods, ‘greenwood marriages,’ and staying up all night to watch the May sun rise were unequivocal activities, which is why the Puritans suppressed them with such pious horror.”

As a Solitary, you would probably have difficulty erecting a maypole and dancing around it to plait the ribbons in the traditional manner. But that doesn’t matter; you can still celebrate Beltain. Dance and song are a big part of the celebrations so don’t hesitate to indulge in both. The sexual union of the God and the Goddess, which was such an important part of this celebration, can be echoed through self-gratification (be you male or female) if you wish, integrating it as part of your ritual (an appropriate point, see below, would be where you say: “Now is the time for the seed to be spilled that fertility may spread throughout the earth”). If you can hold your ritual outdoors, then a balefire burning in the east is a great idea. You can even jump over it as part of your dancing, after the circle has been closed and you can move outside its limits more freely. If you have to be indoors, then many Solitary (and Coven) Witches will burn a Sterno or a large candle inside a small cauldron, or similar, in the east quarter of the circle, so that it may be jumped over when dancing around inside the circle.

The circle and the altar are decorated with things appropriate to the season: seasonal flowers, nuts, apples or other fruit, and so on. Candles, both on the altar and around the circle, can be white, green, or yellow. In addition to the usual altar tools, have a small cauldron, or other suitable container, in the east quarter (inside the circle) containing a large candle. A can of Sterno also will do. This should be lit before you start to open the circle.

The Opening the Circle ritual is done. If it is at, or close to, the full moon or the new moon then the appropriate rite is performed. After that, you return to the altar and ring the bell seven times. Raise your wand high and say:

“Hail to the Mighty Ones; the Lord and the Lady; Herne and Epona! The end of the dark half of the year is at hand. All hail to our Lord! Welcome to our Lady! This is a time for joy and for sharing. The richness of the soil accepted the seed; now is the time for the seed to be spilled that fertility may spread throughout the earth. I celebrate the planting of abundance, the turning of the Wheel. Farewell to the darkness and greetings to the light. Lord and Lady become Lady and Lord, as the Wheel turns.”

Ring the bell three times. You may now dance around the circle, jumping over the “bale fire” in the east as you go. If you wish, you may sing the May Eve chant:

“Oh, do not tell the priests of our rites

For they would call it sin;

But we will be in the woods all night

A-conjuring summer in.

For they would call it sin;

But we will be in the woods all night

A-conjuring summer in.

And I bring you good news,

By word of mouth,

For women, cattle, and corn;

Now is the sun come up from the south

With oak and ash and thorn.”

By word of mouth,

For women, cattle, and corn;

Now is the sun come up from the south

With oak and ash and thorn.”

When you have finished, return to the altar and ring the bell three times. Take up the wand, hold it high, and say:

“Love is the spark of life. It is always there, if I will but see it. I need not seek far for love is within me; it is that inner spark of all that I do. The light of love burns without flicker; it is a steady flame. Love is the beginning and the end of all things. So Mote It Be.”

If you wish, you may again sing and/or dance around the circle. Enjoy the feeling of change. End by sitting (or kneeling or standing) and, in your own words, thank the gods for all they have given you.

Do the Cakes and Wine rite and end with Closing the Circle.

Midsummer/Litha

Midsummer has the longest day of the year. The old Roman name for this time of year was Litha. The sun is at its highest point in the sky, with the God strong and virile. The fertility of the Goddess is at its peak. She is pregnant with the young god and pregnant with the harvest. Here, then, is a balance of fire and water. Here, also, is the turning point where we are about to enter the waning of the year which, eventually, will lead to winter.

The circle and the altar are decorated with things appropriate to the season: summer flowers, heather, oak branches, fruit, and so on. Candles, both on the altar and around the circle, can be white, orange, or yellow. In addition to the usual tools on the altar there is a red (unlit) candle. Also, have a cauldron or other container filled with water standing in the south.

The Opening the Circle ritual is done. If it is at, or close to, the full moon or the new moon then the appropriate rite is performed. After that, you return to the altar and ring the bell seven times. Raise your wand high and say:

“Hail to the Mighty Ones; the Lord and the Lady; Herne and Epona! The Sun shines down from on high, giving its light and life to everything and everyone on earth. Its power and joy enter into the Lady, who is the earth itself, filling her with the new life that is soon to burst forth; the life that will descend into the corn and into the plants and the trees. This is a life that is blessed; that is sacred; that is of the Lady and the Lord.”

Light the red candle from the altar candle and hold it high. Keeping it aloft, walk out to the east and then walk slowly around the circle, letting the light from the candle, representing the God, illumine the circle. As you walk, say the following three times: “Here shines the light and the love of the God, bringing strength and joy to all.” Return to the altar and set down the candle beside the altar candle. Ring the bell three times.

Go out to the circle and walk around to the south. Standing beside the cauldron of water, stand with your feet shoulder-width apart and raise both hands upward and outward. Say:

“Here is the bounty of the Lady; she who, by her love, sanctifies and purifies.”

Lower your arms and kneel beside the bowl of water. Dip your fingers into it and sprinkle yourself with the water saying the following three times: “Blessings from the Great Mother.”

Return to the altar. Take up the wand and hold it high. Say:

“At this festival of Litha I see the sun, my Lord, move on his course. I feel him enter into the Lady and, through her, descend into the fields and the crops. I sense the new life that flows through the Goddess.”

Lower your wand and spend a moment thinking of the blessings you enjoy and of how you might share those blessings with those less fortunate. Ring the bell three times. If you wish, you may sing and/or dance around the circle. Enjoy the feeling of change. End by sitting (or kneeling or standing) and, in your own words, thank the gods for all they have given you.

Do the Cakes and Wine rite and end with Closing the Circle.

Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh is a Celtic name referring to the celebration of the sun god Lugh and actually meaning “the commemoration of Lugh” (since he undergoes death and resurrection in his sacrificial mating with the Goddess). Another name sometimes used is Lammas, from the Anglo-Saxon hlæf mas, meaning “loaf mass,” a celebration of the bread after the corn harvest. This is the time of the first harvest. The god makes love to the already pregnant goddess for the last time, sacrificing himself and passing into the earth. It is through such death and rebirth that the harvest is brought into being.

The circle and the altar are decorated with things appropriate to the season: seasonal flowers such as poppies, fruits (perhaps the first blackberries), grain, small loaves of bread (perhaps shaped like a sun), and so on. Candles, both on the altar and around the circle, can be white, yellow, or brown. In addition to the usual tools, there is a small loaf, or roll, on the altar.

The Opening the Circle ritual is done. If it is at, or close to, the full moon or the new moon then the appropriate rite is performed. After that, you return to the altar and ring the bell seven times. Raise your wand high and say:

“Hail to the Mighty Ones; the Lord and the Lady; Herne and Epona! Here do I celebrate the First Harvest, giving thanks for the continuing Wheel of Life and the continuing fertility of the Earth. May the seeds of the grain be buried in the womb of the Goddess, to be reborn in the spring. As there must be rain with the sun, to make all things good, so must there be pain with joy, that we may know all things. Through the sacred union of the Lord with the Lady is the harvest assured.”

Ring the bell three times then take up the loaf of bread and, with it, dance around the circle, deosil, three times. Returning to the altar, say:

“May the power of the gods pass down to all. May we too enjoy the gift of bounty. May the harvest grow and spread wide to all I love. May the surplus of the land fill our bodies with strength, and may the power of the Lord and the Lady reach down to young and old alike.”

Break off some small pieces of the loaf, laying them on the altar. Take your wand and touch the tip to the pieces of bread, saying: “The blessings of the gods.”

Eat one of the pieces and then place the rest in the libation dish, to be given to the gods later (with the offerings of Cakes and Wine). Ring the bell three times.

If you wish, you may sing and/or dance about the circle. End by sitting (or kneeling or standing) and thank the gods for all they have given you, with the words:

“Lord and Lady I thank you for all that has been raised from the soil. May it grow in strength from now until the main harvest. I thank you for this promise of fruits to come.”

Do the Cakes and Wine rite and end with Closing the Circle.

Autumn/Mabon

Autumn is the other time (after the spring equinox: Ostara) of equilibrium, when the hours of daylight and night are equal. Autumn is a sign that summer is truly over; darkness is conquering light. The accent is on resting after the labors of the harvest, before the start of the winter. This is “harvest home,” the end of the grain harvest. The Goddess is settling into restfulness, starting to take on her crone aspect. As Gail Duff puts it (Seasons of the Witch): “The God, having laid down his life for the harvest, is about to cross over into the Land of Shadows. He stands on the threshold of light and dark, life and death. Soon he will rest in the arms of the Goddess, waiting to be reborn. Like the corn, the God has been cut down, but his seed brings the promise of new life.”

* * *

The circle and the altar are decorated with things appropriate to the season: acorns, pinecones, gourds, poppies, fruit, and so on. Candles, both on the altar and around the circle, can be white, brown, or red. In addition to the usual altar tools, have a dish with an apple on it. If you do not normally use an athamé then have a sharp knife beside the apple.

The Opening the Circle ritual is done. If it is at, or close to, the full moon or the new moon then the appropriate rite is performed. After that, you return to the altar and ring the bell seven times. Raise your wand high and say:

“Hail to the Mighty Ones; the Lord and the Lady; Herne and Epona! Now that the season of plenty draws to its close, I take time to look about me and enjoy the beauties of autumn. Here is a balance of day and night, light and darkness. The wheel turns, and turns again. Death approaches, arrives, and passes on. New life comes into being—and so the wheel turns.”

Lay down the wand and take up the apple. Hold it for a moment, acknowledging the beauty of creation. Take the athamé or knife and cut the apple crosswise. You will see the seeds arranged like a pentagram. As you look at them say:

“Here, within this fruit, is found the symbol of life. Within all life lie the seeds of future lives. My thanks to the gods for their bounty.”

Cut a slice of the apple for a libation, then sit and eat the apple, enjoying it and thinking of the blessings that have come to you—the harvest you have gathered from life. When you have finished, ring the bell three times. If you wish, you may sing and/or dance round the circle. End by sitting (or kneeling or standing) and, in your own words, thank the gods for all they have brought into your life. Feel free to ask for what you would still like to accomplish.

Do the Cakes and Wine rite and end with Closing the Circle.