Introduction

I walked into the room completely unprepared for the reaction that was about to wash over me.

There on the third floor of Building 30 at Johnson Space Center in Houston, I was transported back in time to the late 1960s and early ’70s. As soon as I entered, I was hammered with an overwhelming sense of what had once taken place in this very room. Tears literally welled in my eyes, and I felt unworthy to stand on this hallowed ground. My friend Milt Heflin was a step or two ahead of me and entered before I did, and I was glad of that. I was embarrassed to be standing there like that, but I could not help it.

There was the Trench, and just above it a row of systems consoles. Just across the aisle from the EECOM console on the second row was the capcom station, where Charlie Duke sat as he helped talk Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin down to the lunar surface. Up a row was the throne itself, the flight director’s console. Chris Kraft, Gene Kranz, Glynn Lunney, Gerry Griffin, and Milt had all held court there once upon a time. Amazing.

It was in those few moments when the concept for this book was born. Countless stories about human spaceflight have been told from the air-to-ground perspective, that is, mostly from the viewpoint of the astronauts whose flights this room controlled. A handful of people became relatively well known to the public at large due to what they did here—Building 30 is now named after Kraft, the godfather of all things mission control, and actor Ed Harris made Gene Kranz all the more legendary with his portrayal and “Failure is not an option” line in the blockbuster movie Apollo 13.

Those are just two of the hundreds of people who toiled here, who were among the very best and brightest of their generations, who could make split-second decisions that determined the success or failure of a spaceflight. If the nation’s astronauts were soldiers on the front lines, the denizens of the Cathedral were the personnel behind the scenes directing the whole thing. None—none, not a single one—of NASA’s storied accomplishments would have been possible without these incredible people.

Yet the majority of them have lived in relative anonymity, legendary superstars within the close confines of the NASA community who could walk down a public street and go completely unrecognized. What a shame, because they deserve the recognition. The willingness of those who took part in this grand adventure to contribute was just one of the many, many true joys of putting this book together. More than one former flight controller answered interview requests by taking the initiative of pounding out lengthy and detailed descriptions of their careers. Jerry C. Bostick became a friend, and read drafts of virtually every chapter and made well-intentioned and helpful comments along the way.

Dave Reed was a fount of information. Dave is a stickler for details, and when we encountered some confusion over a long-ago line from a mission transcript, the lengths to which Dave went to set the record straight was simply awe inspiring. Dave and Rod Loe presented me with unexpected items that have become some of my most prized possessions—Dave passed along one of the matchbooks members of the Trench had made up, while Rod sent pristine temporary access badges for the flights of Apollo 16 and 17.

When I called Steve Bales at the appointed time for our interview, he began the conversation by saying that he had already ordered a couple of the NASCAR-related books that I have written and asked if I would sign them for a friend of his. Wait a second. Steve Bales—the Steve Bales, of Apollo 11 lunar descent fame—was asking me for my autograph? Then, when Steve read a draft of the Apollo 11 chapter, he again surprised me by sending me a lengthy e-mail describing in detail what he had liked about it. I immediately printed it out and placed it next to my computer screen.

Others dug into old mission reports and research material to refresh their memories. One did so at his wife’s hospital bedside, as she recuperated from surgery. I sat next to Bob Carlton at his console for nearly two hours one afternoon, listening to him tell war stories and watching as he drew a detailed diagram of the Lunar Module (LM)’s ascent engine and thrusters. I played a few minutes of audio from the Apollo 11 landing, in which Bob can be heard giving his famous low-fuel calls. As I listened to those long-ago voices echo through that room, I was once again reminded that this was hallowed ground. After commenting that the moment had given me chills, Bob’s quiet reply took me aback.

2. These badges, which allowed temporary access into the MOCR during the final two lunar landings, were gifts from Rod Loe to author Rick Houston. Author’s collection.

Me too.

Bob’s passion for human spaceflight was as alive and vibrant in 2013 as it was on that summer day back in 1969. In that, he was far from alone. Decades after laying down their headsets and pocket protectors in mission control for the last time, many seemed almost eager to have their stories told. Well after the last “official” interview question was asked, more than a few continued right on reliving the good ol’ days—but not in some sad, woe-is-me sort of way. What they accomplished meant long hours in an ultra-high-stress environment, but, by gosh, they were working toward putting people on the moon and in orbit on board the Space Shuttle.

What job could ever possibly be better than that?

It is that very kind of deeply felt dedication that Go, Flight! honors. As a direct result of working on this book, I no longer see just Neil Armstrong, Pete Conrad, Alan Bean, and Charlie Duke when I look up at the moon. I also see the people who worked in that magnificent room so long ago. How do I feel about them? Lee Briscoe, the former Apollo back roomer who made it all the way to the flight director’s console during the Space Shuttle years, put it best. “The people who inhabited that room while all this was going on were amazing people, and they did amazing things,” Briscoe said. “It’s just a shame that you can’t preserve those people like you’re going to preserve that room. Those people deserve that kind of place in history.” If this book could be boiled down to just three sentences, those would be the three.

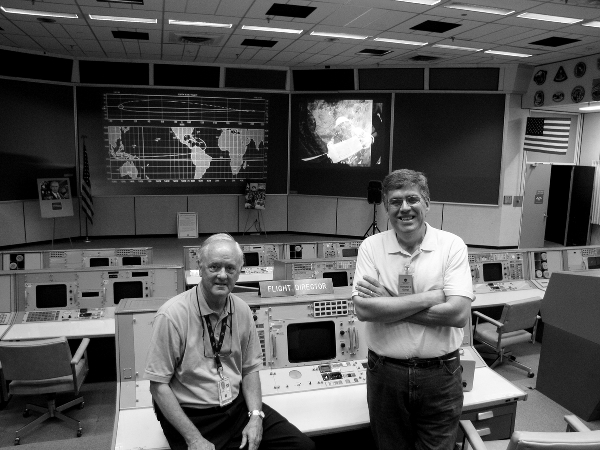

3. Coauthors Milt Heflin (left) and Rick Houston visit the historic third-floor MOCR. Author’s collection.

I also see Milt Heflin when I look at the moon or spot a picture of the Space Shuttle, because he has become the best long-distance mentor I have ever had. Although we have met face-to-face on just a handful of occasions, I would consider him to be a good friend. Maybe it is just a coincidence, but Milt was born in 1943, the same year as my father. Daren is his oldest son with wife Sally. He was born in 1967, same as me. Matt, the younger of Milt and Sally’s two children, came into the world in 1973. So did my kid brother.

Living more than a thousand miles from Houston, Texas, I am no NASA insider. Not once—even at the craziest, silliest, or dumbest question—has Milt ever treated me with anything less than a genuine respect. His contributions to this book in opening doors, checking facts, and obtaining just the right information has made it far better and far more complete than it would have been had I flown solo.

I would also here like to express my deepest gratitude to Keith Haviland, Gareth Dodds, Mark Craig, and David Fairhead for their belief in this project. I cannot wait to see what the coming months hold. The same thanks go to series editor Colin Burgess and the staff at University of Nebraska Press—Rob Taylor, Martyn Beeny, Sara Springsteen, and the one and only Colleen Romick Clark, who served as copyeditor for this book. I have come up with the perfect compromise to our capitalization debates. How about we cap certain words in the third through fifth paragraphs of odd-numbered pages in even-numbered chapters?

I will forever be indebted to collectSPACE.com’s Robert Pearlman; and Emily Carney, creator and chief comment mocker of the Space Hipsters Facebook group. Their sites are wonderful resources for space geeks like me. I deeply appreciate the artwork provided by NASA photo historians J. L. Pickering and Ed Hengeveld. Thanks also go to the Estep family—Sandi, Joe, and Jennifer; as well as the Knights—Fred, Judy, LeeAnn, and Joe; and the Reynolds—James, Lib, Jamie, and Amy. Without their support and encouragement all these years, this book would not be happening.

Also contributing in one way or another were Charlene Hubbard, Gene and Emma Hubbard, Stephen Slater, and Craig Scott. Almost every writer has a particular reader in mind when he or she puts words to paper. For this book, that person is Craig, who is the most enthusiastic MOCR fan I have ever encountered.

Finally, I want to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. Without Him, I am nothing. My wife, Jeanie, is my best friend. Jeanie; our twin sons, Adam and Jesse; and Richard, my son from my first marriage, are my reasons for being.

Rick Houston

Yadkinville, North Carolina

I am still trying to figure out how Rick convinced me to be a coauthor of this book. After nearly forty-seven years in the spaceflight business and now retired, I have done my best to stay away from stressful activities, the non-physical kind. So I was leery of engaging in this project. However, having recognized Rick’s uncanny ability to reach into the heart and soul of his subjects in telling their stories, I agreed.

I agreed because I wanted to help Rick illustrate that what we have done in manned spaceflight was actually quite difficult and that indeed many “unsung heroes” are responsible for “snatching victory from the jaws of defeat.” If we can introduce some of these people to the public, then count me in. Often we made our accomplishments look easy although many times it was anything but. I predict several of my colleagues will be surprised with some of what they find in these pages. I can tell you that I certainly was.

I got to experience some of these moments, having been privileged to work in the third-floor mission control room three times as a flight controller and four times as flight director. My feelings about this place can best be characterized by the word “reverence.” Chris Kraft referred to this place as “this palace.” Gene Kranz called it a “leadership laboratory.” I would later introduce it as a “cathedral.” I think we are all correct.

Getting to where I was qualified to plug a headset into one of the Palace’s consoles took help from a handful of folks teaching, pushing, lobbying, and cheerleading on my behalf. I would not be here today fretting over coauthoring this book without support from Rod Loe, who wanted to make me into a flight controller; Bill Peters, the manager assigned to get me there; Jack Knight, my MCC console real-time ops mentor; Don Puddy, who trusted me to operate in a prime MCC position during portions of the orbiter Approach and Landing Tests; Bill Moon, who accepted me as his prime backroom support for the first Space Shuttle launch, STS-1; Gene Kranz, who selected me to be a flight director in the class of 1983; and finally, Tommy Holloway, who gave me very tough love, preventing me from washing out.

Then there was Randy Stone, one of my dear colleagues during the Apollo Landing and Recovery days. He was a close friend. We lost him on 25 November 2013. If there was one individual I owe my many Mission Control Center experiences to, it is Amber Flight. My career path during and after my MCC years has his footprints all over it. He went above and beyond lobbying for me to take on some new challenge. I cannot think of anyone else who was so steadfastly in my corner, even when I didn’t know I needed somebody there.

Throughout this career, which began on 6 June 1966, I have been fortunate to enjoy the companionship and support of Sally. She along with our sons, Daren and Matt, graciously tolerated my absences and mood swings as I dealt with riding recovery ships supporting Apollo splashdowns and learning to work in mission control. Their love and understanding enabled me to experience the roller-coaster ride through the triumphs and tragedies of manned spaceflight.

Rick was thrilled by the responsiveness of those unsung heroes who agreed to be interviewed. I think what impressed him most is that each of them made it clear that if he needed anything else, then they would be more than happy to accommodate him. He used an impressive number of interviews to piece together the stories, some known, many revealed for the first time. He was so impressed by everyone’s kindness and willingness to talk about their experiences it made him work that much harder to tell their stories. Way to go, team!

Milt Heflin

Houston, Texas

Sirius Flight, EECOM, EGIL, THERMAL, EPS, SMOKHEE