1

Who Did What

At first glance, the room appears to be just another auditorium in just another office building. There are nondescript spaces like it in a million different places all over the world. The carpet is old and a bit bunched up here and there. A few stains dot the floor, the result of who knows how many spilled coffees over the years. There is also a distinct smell to the place, not quite musty and not really even a hint of the tobacco smoke that once hung over the room. Maybe it is a faint remnant of the electronics that once hummed and buzzed here. The odor is neither pleasant nor unpleasant. It is just—distinct.

The four rows of consoles facing the front of the room are almost quaint in their simplicity—workstations feature a rotary dial phone. And canisters, too, to send messages to back rooms via pneumatic tubes, the very same kind of transport system featured at your local bank’s drive-through window. No email or instant messaging here.

Yet if there’s a temptation to dismiss the room out of hand, images of events past begin to sink in and the sheer enormity of everything that took place here hits like a ton of bricks. Only a handful of places inspire such an overwhelming sense of history.

Independence Hall.

Gettysburg.

Westminster Abbey.

Ford’s Theater.

Pearl Harbor.

Normandy.

Jerusalem.

Hiroshima.

Dealey Plaza.

Battles were fought and presidents were murdered at most of these locations, but not in this average-sized room on the third floor of what was once known as Building 30 at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston. It was only after the end of Apollo’s lunar landings that the complex was renamed the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC). Although there was no great bloodshed here, it served as a critical battleground of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Had it not been for the Russians, it is quite likely that the events that took place here would never have happened.

Officially, the room was known by two different names while it was in service from 1965 to 1992—it was the Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR, pronounced “MOH-ker” in NASA-speak) during the Gemini and Apollo era and the Flight Control Room (FCR, pronounced “FICK-er”) during the first decade or so of the Space Shuttle era. It has also been called “the Cathedral” in tones that border on pure reverence because of the things that happened here, as if it were actually a church. Others refer to it simply as “the Palace.” Gene Kranz, on the other hand, called it a “leadership laboratory.” Either way, the point remained the same. So important were the events that took place in this room, it is now listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Think of the words that were first uttered to and from this magnificent room.

You are go for TLI.

Until December 1968, never had a human being left the bonds of Earth’s gravitational influence. Michael Collins was the capcom sitting right there in that seat on the second row, when he gave the call that began the crew of Apollo 8 on its journey to lunar orbit.

Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

And then later . . .

That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

When Neil Armstrong called out those instantly iconic lines, he was talking to this room, and through this room, to hundreds of millions of people watching around the world.

Houston, we’ve had a problem.

When the crew of Apollo 13 announced their dire circumstances in hurried yet never panicked voices, they were talking to this room. And it was the men in and around this room who, over the next three and a half days, spearheaded a massive effort to save the lives of astronauts James A. “Jim” Lovell Jr., Fred W. Haise Jr., and John L. “Jack” Swigert.

Roger, go at throttle up.

As momentous as the events of Apollo 8, Apollo 11, Apollo 13, and so many other Gemini and Apollo missions were, this room is also where some of the darkest moments in NASA’s history began to unfold on a January morning in 1986. When STS-51L commander Francis R. “Dick” Scobee spoke the last words he would ever speak, he was talking to this room.

Most of the people who worked here during the Gemini and Apollo eras were born just as the country was coming out of the depths of the Great Depression, only to find itself embroiled in the even greater agony of World War II. They were from small-town America—one of their hometowns no longer exists—and a good many were the first in their family to graduate from college. And in fact, college had not been all that long ago. Their average age was in the mid-to-late twenties, and there they were, helping to land people on the surface of the moon.

Who were they, and what kind of work did they do here?

There it was, the very first thing anyone who walked in the main door on the left-hand side of the MOCR would see.

The Trench.

The way the folks who worked in the Trench sounded once in a while, that was all anyone needed to see. It was a Trench world, they seemed to figure, and every other controller in the MOCR just so happened to be living in it. The home of the Flight Dynamics Branch might have been on the lowest of four stair-stepped rows, closest to the front of the room and the huge screens that dominated it, but that was just a function of location and darn sure not mission priority. Although Flight Dynamics did not fire the gun at launch, it certainly aimed the trajectory of the bullet wherever it needed to go.

“We were a proud bunch, okay?” said Jerry Bostick, the chief of the Flight Dynamics Branch throughout most of the Apollo program. Then, Bostick invoked the memory of one of the Trench’s biggest legends among its own. “As John Llewellyn used to say, ‘If it’s the truth, it ain’t bragging,’” he continued. “We had a deep appreciation for what the systems guys did, but, of course, we thought all they were doing was providing us with the hardware to do the real job, which was to get them there and back.”

The left side of the first row was technically in the Trench but its positions were not exactly of the Trench. That space was reserved for the booster and tanks station during the Gemini years and then consoles for booster systems 1, 2, and 3 in Apollo. On Apollo 9 and Apollo 11, extravehicular activity (EVA) spacesuits were also monitored from there once the booster controllers vacated not long after launch. The tanks controller watched propellant pressures and temperatures, and was usually manned by a young eager-beaver astronaut. Eugene A. “Gene” Cernan walked on the moon during his command of Apollo 17, but nevertheless he wanted to know why he had not been asked to tell the story of his tanks duty on the unmanned flight of Gemini 2 as well as Gemini 3 and Gemini 4 in the Trench’s self-published book From the Trench of Mission Control to the Craters of the Moon.

A booster 1 controller like Frank Van Rensselaer did not have much responsibility at all, other than to oversee the mammoth 363-foot-tall Saturn V, from about twelve hours before launch all the way through docking of the Command and Service Module (CSM) with the Lunar Module (LM). After that, commands were sent to the spent S-IVB third stage to target it for an impact on the moon near a previous landing site. That way, instruments deployed by astronauts on the lunar surface could pick up vibrations from the impact and possibly allow analysts to determine the moon’s composition in the area.

Booster 2 monitored the S-IVB third stage, while booster 3 kept an eye on the launch vehicle’s Instrument Unit. Their next-door neighbors in the Trench joked with those on the booster consoles, calling them their guests and insisting that they shape up lest they be forced to ship out and move elsewhere in the MOCR. That kind of joking was fine with Van Rensselaer. Although he lived in Houston, the Tennessee native was not technically an employee of the MSC. Van Rensselaer was instead employed by the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, home to the Saturn V and the adopted home of the legendary German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, who designed it.

There were, to be sure, rivalries between Marshall and Houston. “Early on, there was some, let’s say, pushback when we were doing mission rules,” Van Rensselaer said. “The guys at Marshall, their attitude was, ‘Don’t touch the booster. It’ll be fine.’ The guys in the control center were saying, ‘Well, if there’s anything you can do about it, let’s get ready for it.’”

After substantial issues developed during an April 1968 unmanned test of the Saturn V, however, working for a solution finally helped everyone onto the same page. The acceptance from the rest of the MOCR in general and from the Trench in particular from that point on seemed to be “just fine,” Van Rensselaer said. He then continued, “We went through all the sims with them. We were part of the Trench, still are. We have gatherings every now and then, the Trench does. Even though we were the booster guys, they considered us part of the Trench.”

Next were spots for retrofire, abbreviated to retro (just the way all things NASA are always shortened as much as possible); flight dynamics, or FIDO for short; and guidance officers, who were sometimes referred to as guidos—the three positions for which there was no debate as to whether they were members of the Trench. The people who worked this particular trio of consoles had an esprit de corps about them, an air that said they were the ground pilots of these grand spaceflight adventures. Were they maybe just a little bit cocky? Oh, absolutely. There were “The Trench” matchbooks scattered about the control room, and years later, members of the Trench put together a book, DVD, and website to commemorate their work.

That is not all. Kenneth A. “Ken” Young, a rendezvous specialist who once trained as a FIDO and was named an honest-to-goodness honorary member of the Trench, became the MOCR’s unofficial poet laureate by penning a number of original and parody poems through the years. The first stanza of his work “The Trench” read:

Since the very first days of Houston mission control

There has been a unique front row of spaceflight consoles;

Although these vital positions never got much publicity,

The flight operators there controlled the spaceflight trajectory.

This row of three positions, labeled: retro, FIDO, and guido

Began with Gemini and rose to prominence during Apollo.

These crucial controllers, always under fire, yet never known to flinch;

Soon began to call their front-row position as, simply, The Trench!

How The Trench got that name is uncertain but it really makes sense;

For controllers it formed a space mission’s first line of defense!

John the Legend worked the retro console, Young continued, while FIDO had Big Red, the Not-Always-So-Jolly Mental Giant, Bones, Fast Eddie, Stump, and one that rhymed with Superduck. Last came the Fox, Mother, and Gonly at the guidance console.

They were the Trench.

Just to the right of the booster consoles was the retro officer’s domain, and retro was responsible for continually calculating both planned and unplanned maneuvers that could be executed by in-flight astronauts to return the spacecraft to Earth. Jerry Bostick had been a retro, and so were Bobby T. Spencer, Dave Massaro, Thomas E. “Tom” Weichel, Robert White, Charles F. “Chuck” Deiterich, Thomas F. “Tom” Carter, Jerry C. Elliott, William “Bill” Gravett, and James E. “Jim” I’Anson. However, there was one man every fellow retro, every Trenchmate, and everyone else in the MOCR respected and, yes, maybe even feared a little, and that man was the late, great John S. Llewellyn—his middle name was Stanley, but to his NASA coworkers, the “S” stood for “Star,” because that was what he was to them. A star.

Years before joining NASA, Llewellyn experienced things as a member of the U.S. Marine Corps during the Korean War that no human being should ever experience. He was still a teenager when he hit Red Beach during the crucial Battle of Inchon on 15 September 1950, and then was part of a vicious fight that began at Chosin Reservoir two months later. United Nations forces wound up encircled by Chinese troops during that sixteen-day clash, which was fought over some of the worst terrain and in unspeakably terrible freezing conditions. “The Chinese . . . their bugles . . . I could see them coming,” Llewellyn told friend and longtime MOCR coworker Glynn Lunney during an interview for the short booklet From the Trenches of Korea to the Trench in Mission Control. “I saw them when they stopped all their running around in circles like ants down there. I couldn’t believe there were that many people. And I just looked at it. I never saw anything like it in my life.”

The booklet goes on to describe Llewellyn hearing the click of an empty Thompson submachine gun, and then coming face-to-face with the Chinese soldier holding it. Llewellyn killed him, and then spent the rest of the night in the foxhole with his dead foe and hearing other enemy troops passing nearby. The experience impacted Llewellyn in ways few could ever imagine or comprehend, and it was only once in a great while that he might mention the war to his coworkers. Much later in his life, Llewellyn admitted to those around him that he had struggled with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “I guess deep down, there was always kind of a sorrow that I felt for the guy that he had been through all he had been through in the Korean War,” Bill Gravett said. “He had terrible PTSD, and he bore that burden all those years. Occasionally, he would give us a glimpse of that horror that he went through at the Chosin Reservoir. I used to think about that and wonder, ‘How did he survive that?’ I had a lot of respect for the man, I really did.”

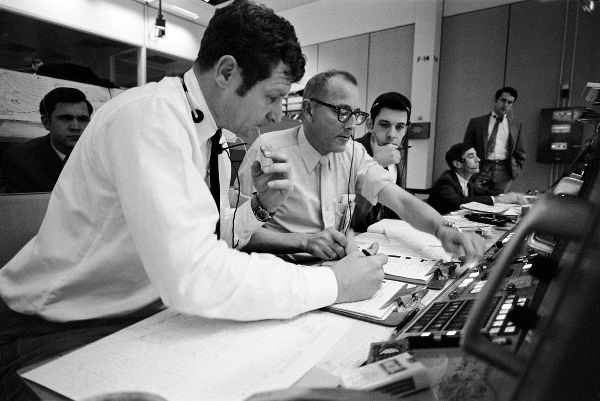

4. John Llewellyn (foreground), Jim I’Anson, and Chuck Deiterich chat in the Trench. Llewellyn, widely known as John Star, was a Korean War veteran who excelled at NASA despite struggling with severe post-traumatic stress syndrome. At the end of the row are Jerry Bostick (sitting) and Bill Boone (standing). Jerry Elliott is seated behind Llewellyn. Courtesy NASA.

Most credit Llewellyn for the Trench’s nickname, either in whole or in part. It was during the flight of Gemini 6 that pneumatic tubes from the messaging system began piling up around him on the first row, and he thought they looked a lot like empty 105-millimeter howitzer shells he encountered in the trenches back in Korea. If that did not seal it, Llewellyn once issued a challenge to the simulation team during a particularly testy debriefing.

Why don’t you come on out here in the trenches and see how tough this really is?

To many, John Llewellyn was a larger-than-life force of nature. He was known to down his fair share of drinks. He could be profane. He spawned countless stories—a good many of which were true.

Some were relatively tame. He could sometimes get the numbers out of order during countdown to retrofire for reentry into Earth’s atmosphere.

10, 9, 7, 6, 8, 4, 5, 3, 2, 1 . . .

That was the kind of thing, though, that could have happened to anybody. What others might not have done was challenge astronaut Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom to a drag race on the beach, Grissom in a gleaming new Corvette and Llewellyn in an old “Official Use Only” Plymouth. Afterward, Llewellyn promptly drove his losing car straight into the surf. When the Soviet Union established some new high ground in the space race, it was John Llewellyn who came banging on the door of Glynn Lunney’s home early in the morning, demanding that the both of them go into work right then and there to do something about it. Legend also has it that while in Australia for work at a tracking station during the Gemini program, Llewellyn was caught trying to sneak into his locked motel. When told by the manager that if he did not like the rules that he could just buy the motel, Llewellyn apparently responded by doing just that.

Then, there was the time he overslept for a shift during the flight of Gemini 5. He raced into work, and after not being able to find a parking spot for his Triumph TR3, drove up the steps to Building 30 and parked directly in front of the door. That stunt got his car pass yanked, but Llewellyn was not deterred in the least. He responded by parking a horse trailer across the street from the main gate and absolutely, positively rode his horse into work. That was Llewellyn, born a hundred years too late, a Wild West devil-may-care gunslinger if ever there was one.

Llewellyn was known as a force in the MOCR as well. “John was somewhat on the short-tempered side against those people that he considered ‘pogues,’” remembered Gene Kranz, who competed in judo with Llewellyn and Dutch von Ehrenfried. “Pogues were people that in his mind did not measure up at being steely eyed missile men. This was particularly noticeable shortly after we moved into the Houston area, when we had a bunch of people who were trying to be flight controllers, but really didn’t have the background for it. I always had to keep John separated from our pogues at the beer parties.”

Peel back a layer or two, though, and the respect his peers had for Llewellyn was as much the result of his service in the MOCR as it was for the agony he endured in Korea. He was an enigma, to be sure. “John and I liked to party, and he partied a lot,” said Jerry Bostick, who along with many others served as an understudy to Llewellyn early in his career. “I lived with this for many years, and many people find it hard to believe, but let me tell you—when John walked into the control center, he was a different person. There was no slouching about him. He was very, very serious. He was dedicated, insisted on doing the right things, very knowledgeable. But then you go to a splashdown party after the mission, and he’s doing cartwheels off the diving board into the swimming pool.”

Asked what he would like for people to remember about Llewellyn, FIDO H. David “Dave” Reed paused and then said with emphasis, “He was unique.” Reed went on to add, “John was, in his own right, a bit of a hinge point for a lot of us. If John started in on a debriefing, look out. You had no idea what’s coming. People would sit back and just wait for it.” On the other hand, Reed continued, “John Star” was also “brilliant. If you looked at him and listened to him, you’re talking major hayseed here. He could come up with some of the more off-the-wall things, but there’s no doubt that in the MOCR, no matter what he said about anybody else, John Llewellyn will always stand out as exceptional in his own right.”

It was true that John Llewellyn’s exploits sometimes overshadowed his gifts while at work in the MOCR, and that was a shame. “I think the thing to be recognized in John’s case was that, yes, there are plenty of stories and plenty of things that he did that were attention-grabbing things,” began Glynn Lunney. “But he was as sincerely dedicated to winning the competition that we had in the Sixties to do the landing as anybody on the team.”

John Llewellyn died 8 May 2012, and his ashes were buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. Shortly before Llewellyn’s passing, Lunney wrote that dealing with the trauma of Korea and its aftereffects “ultimately led to profound changes in John, and all for his own good. He has earned an understanding of himself and sees his life much more clearly. He is also at peace with the past and with himself.”

Next in line on the front row of the MOCR was the FIDO console, where men like Jerry Bostick, Dave Reed, Jay H. Greene, Philip C. Shaffer, George C. Guthrie, Edward L. Pavelka Jr., William J. “Bill” Boone III, Maurice G. Kennedy, and William M. “Bill” Stoval labored. Essentially the quarterback of the Trench, FIDO was responsible for the trajectory of the spacecraft from liftoff to splashdown. Tracking the position with ground-based radar and onboard guidance systems, FIDOs calculated the maneuvers that had to be made in order to get both the CSM and LM where they needed to go. It was the only other position in the control center besides booster 1 and the flight director that had the ability to directly call an abort during launch.

After working briefly at Langley, Jerry Bostick moved to the Mission Planning and Analysis Division (MPAD) in Houston and also supported Mercury retro officer Carl R. Huss from a back room at Cape Canaveral in Florida. When Huss suffered a non-life-threatening heart attack shortly after the last flight of the program, Bostick leapt at the opportunity to move into the front room and serve as an understudy to new prime retro John Llewellyn for the first three unmanned and manned Gemini missions. Beginning with Gemini 4, which shared flight control monitoring between the Cape and Houston’s new Mission Control Center, Bostick switched over to work as a FIDO. “I just thought it was kind of a no-brainer,” Bostick said. “It was a step up. The FIDO is really the team leader in the Trench, over the retro and the guidance officers. I wanted to do it.”

Dave Reed seemed to be a perfect fit for work as a FIDO. Bill Stoval once said that nobody had ever prepared for a mission like Reed did, and he definitely had a point. Checklists? Reed put together his own detailed masterpieces for virtually every phase of a flight. Most everybody prepared similar lists in some shape, form, or fashion, but that was just one facet of Reed’s preparation regimen. “I spent a lot of time going over all this stuff and drawing up my own,” Reed said. “I don’t know exactly what Stoval would be referring to, but I know Maurice Kennedy made a similar comment. I don’t know what in the hell they saw, but I always have been a stickler for detail, I guess. I wouldn’t quit until I felt I knew that entire checklist by heart.” The Wyoming native’s attention to detail also manifested itself in debriefs following mission simulations. If Reed felt he had something to discuss, he was going to discuss it until he felt the subject had been covered to the fullest. “His debriefings during the simulations would go on and on and on and on,” Chuck Deiterich remembered. “We [those in the Trench] always went first, so the systems guys didn’t get as much time to talk as we did.”

Not only were the men of the Trench a proud bunch, but they also took care of their own. When Glynn Lunney and his family spotted Bill Stoval walking along the road in front of MSC on a hot and humid day in early July 1967, the newly hired FIDO had apparently not yet exchanged the wardrobe from his native Wyoming for one more suitable to Texas summers. Stoval, wearing a wool shirt and thick corduroy pants, was taken in by the Lunneys. He would go on to find Fruit Loops cereal in his beloved Corvette after babysitting for Lunney, and he became a target for water balloons and eggs as the “rug rats” grew older. One of those rug rats was none other than Lunney’s son, Bryan, who would also go on to work the flight director’s console.

The right end of the first row was reserved for the guidance console, manned by flight controllers such as Raymond F. Teague, Neil B. Hutchinson, Kenneth W. “Ken” Russell, Granville E. “Gran” Paules, William E. “Will” Fenner, J. Gary Renick, C. Roger Wells, Willard S. “Will” Presley, Stephen G. “Steve” Bales, Jerry W. Mill, Jonny E. Ferguson, and B. Randy Stone. Guidance officers stood vigil over ground-based and onboard navigational systems and guidance computer software, and were also responsible for maintaining the onboard attitude reference system. If any of them ever got stuck for an answer, the first logical thing to do was check with their section head, Charley B. Parker. He was, after all, the original guido.

Parker was born and raised 120 or so miles northwest of Houston in the tiny hamlet of Concord, Texas. After the war, the train stopped coming through and Concord dried up just like that. Trying to find it on the map today is impossible, because it is not there, swallowed up by the surrounding towns of Centerville, Juet, and Marquez. Hardscrabble sharecroppers, the Parkers had little to no money, but neither did anyone else they knew. His father, Floyd, never went past the eighth grade, while mother Ora Bell—known as Jack, although even she was not quite sure why—made it through high school. Despite their meager means and educational background, Parker had been expected to go to college and get a degree for as long as he could remember, almost as if he did not have a choice in the matter. After a lackluster first couple of years at Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas, a stint in the army was all it took to convince Parker that school was not all that bad an option after all. Refocused, he graduated with a degree in electrical engineering.

Like so many others who went to work in Houston in the early 1960s, Parker was in the right place at the right time. A digital guidance computer was onboard the Gemini spacecraft, and it could take over and fly the Titan II launch vehicle during ascent in case the primary system failed. The guidance computer then acted as the primary system during descent and flew the two-seater spacecraft back into the earth’s atmosphere. With such newfangled gadgetry on board, somebody needed to monitor and update it all back in the MOCR. The solution was to add a new position in the sparkling new, state-of-the-art control room—the guidance officer. The contractor TRW had done a study on how to monitor the guidance systems during ascent.

“I was the guidance officer when I got there,” Parker said. “There was nobody else in the branch working on that problem when I got there. Using [TRW’s] study as a basis, I just built on it to develop the console.” The console would be a fairly special one with three display tubes instead of the standard two. Strip charts went on the left and right monitors, with a digital display shown on the one in the middle.

Together, the three Trench positions formed such a close working relationship in the MOCR that it might help explain the first row’s camaraderie away from it. “Those three positions were almost interchangeable,” Parker continued. “We understood what the other person was doing, and understood what their problems were. It was really almost one position, with three people operating. We kind of had a motto that the Trench was where the action was, and the other people, oh, they were just systems geeks. We were actually kind of an insufferable bunch.”

Proud? Yes. Cocky? Probably. Insufferable? When it came to the Trench, like beauty, that was in the eyes of the beholder.

Like a line of demarcation, the aisle to and from the back of the room that began a third of the way down the second row separated two decidedly non-systems-oriented positions from those that dealt with the inner workings of two spacecraft.

The left-most workspace on the second row belonged to the flight surgeons, who were responsible for the health of the in-flight astronauts. Doctors Charles A. “Chuck” Berry, Willard R. Hawkins, John F. Zieglschmid, Kenneth M. Beers, George F. Humbert, and Sam L. Pool watched over their flock like mother hens, but even distinguished physicians like them could get tripped up once in a while. Although there was usually not a lot going on at the surgeon console during a simulation training exercise, the physicians had to be there and paying attention just in case. On at least one occasion, however, the physician on duty got caught napping during a test. “It was extremely boring during the simulations for them to be in mission control, so the training people decided they would do something,” said Joseph N. DeAtkine, a longtime systems flight controller. “They went to one of the hospitals in Houston, and they got the EKG of a real patient having a heart attack, and, I think, dying. They brought that back and programmed it into the simulation. During the launch, they played this for the surgeons into their console.”

The doctor, as it happened, missed the foreboding reading. Afterward came the sim team’s turn to drop its bombshell. “The training people came online and said whether you did right or did this wrong, or you missed that or you did that right,” DeAtkine continued. “But when they came to the surgeon, they said, ‘Oh, by the way, astronaut so-and-so died.’ Of course, all of mission control just busted out laughing. It was very embarrassing for the doctors. I think from then on they paid attention during the sims.”

The console between flight surgeon and the aisle was where the capsule communicator (capcom) took up residence. With only four exceptions during the four-shift flight of Apollo 12—when Dickie K. Warren, James O. Rippey, James L. Lewis, and Michael R. Wash took over—capcom duties were handled exclusively by astronauts during the Gemini and Apollo programs. The theory was that pilots could communicate better with fellow pilots, whether they had actually yet flown in space or not. Their training and language were the same. If some felt that landing a capcom assignment meant that they were one step closer to a flight assignment of their own, that was not the case for Thomas K. “Ken” Mattingly II.

“I suspect everybody’s got a different answer,” Mattingly said with a chuckle. “In my case, I had no aspirations whatsoever that I was going to get to fly in Apollo. Our class had the moniker of being the ‘Excess Nineteen,’ and it certainly appeared to me that was the case. So any job that got you involved in activities that were current or that would give you some insight was a plum assignment in my book.” After being bumped at the last minute from the ill-fated flight of Apollo 13, Mattingly flew as the Command Module pilot on Apollo 16.

Along the way, the voices of the men who served as capcom became part of history. It was an astronaut capcom who sent Apollo 8 on its way to the moon; who talked Eagle down to the lunar surface, and another who talked Neil Armstrong down its ladder; who passed a fix up to the lightning-struck crew of Apollo 12; who talked the crew of Apollo 13 through the first few minutes of its crisis; and who spoke the final words a Space Shuttle crew would ever hear from the ground.

Just across the aisle to the right of the capcom console rested the first of four systems consoles—two for the CSM and two for the LM. The systems monitor had been responsible for almost all of the tiny Mercury spacecraft, while an environmental observer worked closely not with systems, but with the flight surgeon. “Most of the people recognized that this was sort of an aberration for how the Mission Control Center should work,” Gene Kranz remembered. “It was not surprising, because to a great extent, the teams we fielded down at the Cape were like sandlot softball. Basically, we didn’t know who would be the team members from the systems side of the house until we got very close to launch. Then, we’d borrow them from somewhere. It was sort of a part-time job for them.” With so much more telemetry streaming down from the Gemini and Apollo spacecraft, controllers were dedicated to watching over their innards.

The first systems console in Houston was reserved for the CSM’s environmental, electrical, and communications (EECOM) officer. The spot was responsible for communications through the flight of Apollo 10, and while those duties were consolidated into another position in the MOCR, the “COM” in EECOM remained. William C. “Clint” Burton, John A. Delmont, Charles L. “Charlie” Dumis, Richard D. “Dick” Glover, Lloyd V. Howard, Thomas R. “Rod” Loe, Seymour A. “Sy” Liebergot, J. Steve McClendon, William J. “Bill” Moon, and Craig Staresinich all sat the EECOM console at one time or another. And then there was John Aaron, who described the duties of the job as being “in charge of all the utilities that support the enterprise.” Things such as power, environmental control, thermal control, life support, docking system, abort systems, pyrotechnics, sequencing, and instrumentation—it was all included in an EECOM’s job description.

Aaron knew the job inside and out, up one side and down the other. Better yet, he was secure in the knowledge of how his job impacted others in the control room. That is precisely where he gained the monumental respect of his coworkers. “If you polled all the flight controllers as to who they thought was the most capable and competent guy that ever sat in the control center, besides Chris Kraft, they were going to say John Aaron,” remarked Jerry Bostick—and this, from the head of the Trench. “I still believe that. It was very satisfying to see when you were on the same shift as John, because you knew he knew what he was doing and knew how his job interacted with mine.”

The truly amazing part of Aaron’s story at NASA was that almost as soon as his feet hit the ground in Houston, he was ready to pack up and head back home. Surely, it had all been a mistake. Aaron was a farm boy who grew up in rural Oklahoma, almost completely unaccustomed to the bright lights and big city of Houston. The climate was arid back in Oklahoma, a far cry from his new home’s heat and humidity, not to mention its mosquito-ridden plains and marshes. It was hard enough to cope with such problems, but over and above that was the very real fact that Aaron essentially had no idea what the space program was all about. He had been in a bubble in college, trying to make ends meet and working toward becoming a teacher so he could afford the herd of cattle he wanted to build up.

Aaron showed up for work at NASA only to find that his new coworkers were speaking what seemed like a foreign language in one strange acronym after another. The air conditioning was broken in the building to which he reported—this was during construction of the MSC campus down on the prairies south of town, when the agency was spread all over town—and people seemed to be piled on top of each other.

As if that was not enough, Aaron’s father was getting older and was very ill at the time. As the only son—and next-to-the-youngest child—in a family of eight children, he felt a deep-seated need to do his duty and return home to help on the farm. Houston seemed as far from there as it could possibly have been. Aaron was thinking of leaving, and he tried rationalizing the move with his parents, John and Agnes.

Dad and Mom, you guys are in your seventies and you’re having a hard time here. What do you think about me just coming back for a couple of years and helping you transition this operation?

Their response stuck with Aaron for more than half a century.

Son, we are in the September of our life. Do not worry about us. You should carry on and pursue your life. You’ve got a very bright future in front of you. Don’t feel like you’ve got to come back here to help us, because that would be the wrong thing for you and your family to do.

Cheryl Aaron, John’s wife, was even more to the point.

We’re not going back.

That was that. And if members of the Trench ever deemed a systems controller fit for honorary membership, it would more than likely be Aaron and for precisely an attitude like this one: “If we had a good day, we all knew that you don’t even need ground controllers like me,” Aaron began. “The crew had good knowledge of the spacecraft. They had canned procedures and so on. We were there for insurance. The crew depended on the ground to get certain trajectory information. As an EECOM, I was there in case they had a bad day because they could basically fly the thing to the first element of surprise without much help from me. That was the motivation. My real job was to be able to be there with the right answer when the unexpected happened.”

Just to the right of EECOM on the second row was the flight controller who took care of the guidance, navigation, and control (GNC) hardware in the CSM. Those men included Gerald D. “Gerry” Griffin, Gary E. Coen, Richard B. Benson, John A. “Jack” Kamman, Briggs N. “Buck” Willoughby, Lawrence S. “Larry” Canin, William J. “Bill” Strahle, Raymond S. “Terry” Watson, Neil Hutchinson, Joe DeAtkine, Richard Fitts, and Ronald Lerdal.

DeAtkine, an army brat whose brother David also worked at NASA for years in the MPAD division, started out as an instrumentation and communications (INCO) officer during the October 1968 flight of Apollo 7 and then ventured halfway around the world to the tracking station in Carnarvon, Australia, to work as EECOM for the unmanned Apollo 4 Saturn V test a month later. That was only a temporary move, and he found himself comfortable as an INCO through the first lunar landing. It was then that the INCO position was consolidated. DeAtkine moved—when he got moved, according to him—over to GNC for the flights of Apollo 14 and 15. “If I had any say in it, which I did not, I would’ve gone with the INCO job over in Ed Fendell’s area,” DeAtkine said emphatically. “But they moved me over there, and GNC is actually more interesting, really. It got me into an area I’d never worked before.”

DeAtkine described work on the GNC console as “mundane” as much as 95 percent of the time during a flight. Beforehand, though, the sim teams had long put him and other systems analysts through the wringer. “They would put these failures in, and then we would look at the mission rule and see what to do,” DeAtkine said. “Sometimes, it turned out the mission rules weren’t quite what they should be.” Along with mission rules came malfunction procedures that DeAtkine compared to an automobile repair manual.

If the problem is this, then do that.

If it is not this, then try that other thing.

If it is neither of those, then try something else altogether.

If all else fails, just keep looking.

As in the Trench, the two CSM systems controllers had responsibilities that were quite connected. “The systems officers sat side by side and worked closely together, because quite often, an electrical problem would effect a navigation system or vice versa,” Gerry Griffin concluded.

The same went for the next two positions on the second row. These oversaw the guts of the Lunar Module during the Apollo years, while in Project Gemini, that space was occupied by navigation and systems controllers for the Agena docking target. A handful made what seemed to be the perfect transition, Gemini to Apollo, Agena to the LM. “We had two spacecraft in Gemini—we had the manned spacecraft and the unmanned spacecraft,” explained Bob Carlton. “When we moved into Apollo, you had kind of a similar situation with the CSM and the LM. The guys who had worked on the Agena kind of naturally fell heir to the LM.”

The responsibilities during Apollo were so similar to the Command and Service Module, the two new LM sections were actually referred to as GNC and EECOM in a 9 June 1967 announcement. The jobs were close in duty and proximity. To the immediate right of the CSM’s GNC console was that of the LM’s telcom/telmu officer. The telemetry, electrical, and communications (telcom) position was renamed telmu following Apollo 11 when responsibility for the moonwalkers’ Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) was added and communications moved to the consolidated INCO position. The EMUs had until then been monitored down on the far left-hand end of the Trench, after the spots were vacated by the booster controllers. William L. “Bill” Peters, Donald R. “Don” Puddy, Jack Knight Jr., W. Merlin Merrit, Gary C. Watros, and Robert H. “Bob” Heselmeyer all worked the console.

Bill Peters sat the telcom console during the flights of Apollo 9 and 10, and then moved down a row to watch over Apollo 11 Lunar Module pilot Buzz Aldrin’s EMU during the first moonwalk. After that, it was back up to the merged telmu position from there on out. “It wasn’t that much additional effort,” Peters said. “While the Lunar Module is sitting on the ground, you’re not worried about things that happen while it’s flying. So you transition your workload effort over to the suit.”

The last spot at the right end of the second row belonged to the control officer, who handled guidance, navigation, and control systems for the LM. Harold A. “Hal” Loden, Jackson B. Craven Jr., John A. Wegener, Richard A. “Dick” Thorson, and Larry W. Strimple served as control at one time or another, and it was Bob Carlton who was their section head early in Apollo. New hires were coming on board almost daily, it seemed, with branch chief James E. “Jim” Hannigan heading out on recruiting trips to college campuses and Carlton working the phones to staff the front and back rooms. “I ended up with close to thirty people after we got all powered up for Apollo,” Carlton said. “Here a whole bunch of newcomers came in, don’t know nothing from nothing, kids fresh out of college.”

Add in a few that had been handpicked from the air force, who were bright and the cream of the crop but inexperienced in flight control and systems expertise, and Carlton had his hands full in trying to get everybody all trained up and ready to go. “The training of all those people was a mind-boggling task,” he said. “You were trying to teach them how to understand the engineering aspects of their systems details. They were responsible for the propulsion system, the guidance system, the RCS system, et cetera. They didn’t know what an RCS system was.”

Slowly but surely, the new hires learned. One of Carlton’s favorite teaching methods was to have them draw and diagram systems overseen by the control officer. “We had to troubleshoot things in a matter of seconds for problems, and the old set of drawings they used in engineering just wouldn’t cut it,” Carlton said. “So I used the drawing system that we had as a double-barrel sort of a tool. I would put a new engineer on there and say, ‘Okay, you’re an RCS man and I want you to upgrade our drawings here for the RCS system. I don’t like it. I want you to redo it.’” What Carlton was actually after was an improvement on the drawings, but also for the new guy to understand the system in the process. “When he drew it, he learned it,” Carlton concluded. When delivery of the Lunar Module was delayed, some within NASA found themselves frustrated. That was not the case for Carlton. “It was a lifesaver,” he admitted. “I was so far behind the power curve, working until midnight, didn’t see how in the world I was ever going to make the schedule. Every time the contractor came in and said we can’t make the schedule, deep down, I rejoiced.”

The task at hand—landing men on the moon before the end of the decade—and Carlton’s responsibilities within that task sometimes got the best of him. Though he mellowed considerably following his NASA career, he could sometimes be a pill during it. “Sometimes, you had individuals that had an abrasive personality, and you’re probably talking to one of them right now,” Carlton granted. “In retrospect, it’s almost a little embarrassing to think back to how overbearing I was and how cocky I was. I rubbed a lot of people the wrong way.” A time or two, Carlton continued, he and a particular FIDO would “draw sparks” on each other in disagreement. “It was a two-way street, probably more my fault than it was his,” he added. “Some of that was personality. Some of it was difference in opinion on how you should be doing things and so forth.”

Overall, there was what Carlton called a “stupendous harmony” among controllers who were all working toward the same goals of mission success and safety. Generally, though, disputes arose over such things as mission rules and what-if situations. “That’s where you had differences of opinions, and that’s where you drew sparks,” Carlton said. “The whole team would get together and we’d have great debates about how we should react to various problems. Then we wrote those decisions down as mission rules. Emotions ran high during those debates about mission rules.” The important things to remember, though, are that these debates took place outside the MOCR, before a flight, and that input came from several sources. According to Gene Kranz, nearly 30 percent of pre-mission planning was spent on developing mission rules, which represented “a meeting of the minds between the flight director, mission controllers, flight crew, and program office.”

Once on console, those sometimes heated conversations were over. “After we got through wrestling over all those mission-rules debates, there would be a decision made,” Carlton said. “The flight director would say, ‘I hear you, Carlton, but shut up. This is what we’re going to do.’ Once that decision was made, you laid aside any discussion from that point on. I think there was whole-heartedly an attitude in all of the team that once you got the mission rule resolved, then you went and implemented it.”

If ever anybody in the MOCR could have come close to matching John Llewellyn in terms of sheer force of personality, it almost certainly would have been Edward I. “Ed” Fendell.

His was a journey to mission control and the INCO console on the far left of the third row that was one of the most unlikely of them all. Fendell graduated in 1951 from Becker Junior College in Worcester, Massachusetts, with a degree in merchandising, of all things. The two-year degree was as far as the man who would one day be head of the Apollo Communications Section would ever go in terms of formal education outside NASA.

Fendell joined the army reserves as an artillery spotter while still in junior college, and when he tried to join the coast guard after graduation, the waiting list was several months long. Instead, he walked just a few doors down the street and signed his papers for the air force. He was given an IQ test shortly thereafter that changed the course of his life. “That’s no shit . . . that’s the truth. I wasn’t interested in school. I wasn’t interested in anything,” Fendell said in his distinctive tell-it-like-it-is manner. “When they gave all this IQ test that they did, I was up at the top. I didn’t know I was smart. I had no idea. I got into air-traffic control, and the next thing I knew, was first in my class.”

Specializing in talking aircraft down in bad weather, Fendell landed at the Federal Aviation Administration after leaving the military. When he turned up at the Cape at one point, he landed a job offer from NASA to serve as a remote-site capcom. His learning curve was a steep one. In the early 1960s, there was no preexisting knowledge base on how to go about getting up to speed in the human spaceflight business. “If you had a question about something, if you didn’t know an area, you couldn’t go to a library and get a book. There was no book,” Fendell said. “There was no training program. There was no workbook for someone like me who didn’t know orbital mechanics from a frickin’ hole in the ground.” That meant when Fendell needed to better understand something, he had to go find somebody to explain it to him.

It was hard enough to comprehend the complexities of building a human spaceflight program from scratch, but just imagine what it must have been like to be in Fendell’s shoes in those days. He was not an engineer. He did not have so much as a degree from a four-year college. Yet there he was, right in the thick of it all. “Everybody was your friend and you were everybody else’s friend,” Fendell continued. “Everybody worked together, and when you screwed up, everybody told you that you screwed up.” Official post-simulation debriefings were an important part of the learning process, but it was post-mission parties at the Hofbraugarten German Village Restaurant in Dickinson, Texas—about ten miles from the MSC campus—where flight controllers really got down to business.

“The only people who went to that party were the flight controllers and the astronauts—no one else,” Fendell began, as if warming up to the story. “There was no, ‘I’m bringing my friend or my girlfriend.’ You went down there, you drank beer, and everybody talked about you and they talked about all the shit that you did wrong. Everybody listened and heard when somebody stood up there and said, ‘That damn Fendell did the following thing, and that was the dumbest son-of-a-bitching thing in the world . . . tah-dee, tah-dah, tah-duh, tah-dumb.’” And this . . . this was the most important part. “You stood there and took it, or you packed up and you went home,” he concluded.

Work became a way of life for Fendell. He would never even know if he or anybody else for that matter got paid overtime, not that he cared much one way or the other. That is not to say, though, that he was all work, all the time. “One day, I picked up this chick and we spent the night,” he remembered.

The morning after, their conversation went something like this.

Where are you going?

I’m going to work.

Fendell’s date was incredulous.

You’re what? Today’s Saturday. What am I going to do?

This is what it was like to be around Ed Fendell back in the day, because his response was so classically him.

Well, you can either stay here, or you can get your ass up, go home, and I’ll call you later. You understand what I’m saying? I’m going to work. I write mission rules on Saturday morning.

After Gemini and his service at various remote sites around the world, Fendell headed back to Houston to serve as assistant flight director before assuming responsibility for the INCO position following the fateful flight of Apollo 10. The move saved Fendell’s career at NASA. He had so despised the role, he came close to leaving the agency not once but twice. The first time, he had an offer from TRW in Los Angeles, and the other, from a proposed National Hockey League expansion franchise in Seattle, Washington.

He stayed to oversee data, voice, and video communications and the group of INCOs, which in Apollo came to include Joe DeAtkine, Earl W. Thompson, Richard T. “Dick” Brown, Thomas L. Hanchett, James R. Fucci, Harley W. Weyer, Granvil A. Pennington, Alan C. Glines, Gary B. Scott, Harold Black, and Lawrence L. D. “Larry” Armstrong. Several—including Thompson, Weyer, Pennington, and Armstrong—had moved just one spot to the left from the operations and procedures console. Fendell stayed on through the early years of the Space Shuttle program, serving all the while in communications.

The operations and procedures (O&P) officer was primarily responsible for data configurations and the extensive O&P handbook that had been compiled from each of the various branches in the control room. “During the flight, we were responsible for any changes or updates that were necessary because of something that came up during the flight that we hadn’t foreseen,” Gary Scott said. “We were responsible for making sure that was coordinated with the proper people and sent out to whoever needed to see it. We also kept up with making sure the data retrieval procedures and configurations were correct for whatever phase of flight we were in.” Along with those who eventually moved to work as INCOs, Larry W. Keyser, David F. Nicholson, Axel M. Larsen, William Molnar Jr., James O. Covington, Joe M. Leeper, Joseph Lazzaro, Joseph G. Fanelli, Harold Black, Richard B. Ramsell, Kim Anson, Alan Glines, William B. Wood, and Maurice Kennedy all served at the O&P console at one time or another during Apollo.

Next to procedures was the assistant flight director (AFD) console, and if the title sounded relatively self-explanatory, it nonetheless became one of the MOCR’s most controversial positions. The role was the brainchild of Gene Kranz, who had worked procedures under original NASA flight directors Chris Kraft and John D. Hodge during the early Mercury days. “This goes back into, I think, the difference between myself and some of the other flight directors,” Kranz said. “Throughout my entire life, I never minded anyone looking over my shoulder, willing to give help. I considered him my co-pilot. When I was getting ready to make tough decisions—they’re short term, they’re quick, they’re irreversible—I liked to have somebody saying, ‘Yeah, I think that’s the way we ought to go.’”

Manfred H. “Dutch” von Ehrenfried served under Kranz in that capacity during a handful of Gemini flights, early in Kranz’s career at the flight director’s console. Von Ehrenfried would come to respect the man as a friend, mentor, and brother. “You start spending eight to sixteen hours a day with Gene Kranz, you’re going to learn something,” von Ehrenfried said. “Many times, we would work so hard, I would just kind of hope he would faint or something so I could get a break.” To von Ehrenfried, who also worked as a judo partner with Kranz, the AFD’s job was as simple as getting the flight director the information he needed when he needed it.

Gene Kranz considered the AFD a safety valve, a wingman, he said, to keep watch over his six. He had flown the demilitarized zone in Korea and the Taiwan Strait during his time in the air force, and he was glad to have somebody watching his back. He sometimes flew in air shows, and he always had someone calling off altitude, airspeed, and show sequences. Not all wingmen made element or flight leader, but they were still good wingmen. They checked their egos, just as Kranz tried to do when he crawled into the cockpit or sat down in his chair at the flight director’s console in mission control. If he needed help from a wingman in either arena, so be it.

To more than one of the men who served in the position, however, there sometimes seemed to be a rather large difference between working as an assistant flight director and as an assistant to the flight director. Gerry Griffin felt whatever difference that existed was the result more of the personalities involved and how they utilized the AFD than of any outright political motives in the MOCR. He had a point. The men who served as flight director were different, and they did approach their jobs in different ways. Gene Kranz took fastidious notes, while Griffin took few. Others joked with Glynn Lunney and told him to slow down, that they were not quite as smart as he was.

Griffin did not mind the help of the AFD, using John H. Temple as much as possible, but that was not the case for other flight directors. “My problem with this subject was the surmise that it was the preferential position in the competition for—or even be the main path—to being selected for flight director,” Lunney said. “Since all the AFD came from the same branch—one of four or five in the Flight Control Division—it was an accident of where one entered the operations division. This seemed a poor prerequisite for flight director. There was lots of talent in the other branches, and I could not imagine deselecting that pool. Plus, the help I got was widely different, depending on who the AFD was.”

Neither was Sy Liebergot a fan of the position. “Quite frankly, the positions of operations and procedures officer and assistant flight director were pretty much non-positions,” said Liebergot, who served in both jobs during unmanned Saturn launch vehicle tests before moving down to the second row and the EECOM console. “The assistant flight director position was . . . nothing more than a ‘go-fer.’ In fact, it was that reason that I ended up being an EECOM because Lunney on [the Apollo 4 Saturn V test] called me over to his console and told me very clearly that if I thought that if he couldn’t perform his duty as a flight director that I had another thought coming. He said, ‘I will crawl over broken glass to keep you from taking this position. You ought to find something else to do.’”

Liebergot concluded by recalling how members of the Trench would sometimes phonetically pronounce the position’s abbreviation as “aphid”—which he noted is “a small, sucking insect.”

Charles S. “Charlie” Harlan started his NASA career at the agency’s headquarters in Washington DC before moving south to Houston in March of 1964. While he took a little bit of heat early on from coworkers over making the transition from HQ, Flight Operations was the place to be. He threw himself into doing double-duty by monitoring the Gemini program’s Titan II, and after launch, moving up to the AFD console. Although that was his home throughout most of Apollo, Harlan was aware of the position’s limitations. “It was thought to be an infringement on the flight directors by some. Others, it was thought to be not substantive in nature,” he admitted. “I could count on coming to work and getting a ration from somebody.”

During Apollo, the AFD duty fell to men like Harlan, Liebergot, Fendell, Temple, Harold M. Draughon, Jones W. Roach, William E. Platt Jr., Perry L. Ealick, Charles R. “Chuck” Lewis, Larry Keyser, David E. Nicholson Jr., James Covington, Howard C. Johnson, Joe Leeper, and Barry Wolfer. Of all the men who sat the AFD console during Apollo, only Lewis and Draughon ever became flight directors themselves.

Back in Mercury, Lewis had gone to school on spacecraft systems and learning Morse code before he was thrown out into the world at the tracking station in Zanzibar, East Africa. Traveling to the different sites he worked and seeing the world the way that he did turned out to be what he called one of the better parts of his career. “I wasn’t trying to promote myself into a control-center position that time,” Lewis said. “I wasn’t even thinking about it.” Fate soon intervened, and he was pulled back to Houston to work on Apollo requirements for the control center. One thing led to another, and Lewis found himself in the position of AFD. “In my opinion, the AFD role was primarily preflight,” Lewis said. “We did a lot of mission rules work, reviews, following up on action items for some of the flight directors. Some didn’t want you involved that much. I really felt the emphasis was probably preflight, as opposed to support during the flight.”

During a mission, Lewis might occasionally mention it being a minute to loss of signal or some such—and not even over the comm loop, because their consoles were right next to each other. Other than that, however, that was just about the extent of it. “I don’t recall a case where he left and left me in charge, so to speak,” Lewis said. “If he was not at the console and somebody called him, I said, ‘This is AFD. Flight’s not here. I’ll pick it up if you like, or you can hold for Flight. He’ll be back in a couple of minutes.’ I never did feel comfortable trying to step into the flight director’s shoes when I was assistant flight director, because you can’t have two quarterbacks on the field at the same time.”

If there was doubt over the AFD’s duties, the same could not be said for the flight director. Separated by a narrow aisle on either side, as if to fully designate the spot as the throne of all thrones in the room, the very next console in the MOCR was reserved for the flight director. Written by Chris Kraft, this job description was easy enough to comprehend.

The flight director may, after analysis of a flight, take any action necessary for mission success.

Kraft was everything that it meant to be a flight director during Mercury, even as the job steadily evolved into the one he envisioned. John Hodge joined the exclusive club for the final flight of the Mercury program, that of Faith 7 and astronaut Leroy Gordon Cooper Jr. in May 1963. Those ranks were exactly doubled, to a total of four, after it was announced in a 4 September 1964 press release that Gene Kranz and Glynn Lunney had also been named as flight directors. They were, the announcement read, “responsible not only for making operational decisions involving spacecraft performance, but also for seeing that flight plans are followed and that crew safety is assured.”

Regardless, Glynn Lunney’s role model for the new job was none other than his mentor, Chris Kraft. “That was a very big deal,” said Lunney of his promotion. “Chris Kraft had become a legend by the time we got to that point. We worked with him through the Mercury flights, and we saw his leadership. We saw how he managed things. We saw how he delegated and trusted people, but then made sure they did the job. He trusted us to do big things.”

The kind of faith that Kraft showed toward his charges—as stern as it could be at times—was returned in full at virtually every turn. “He was the model that most of us sought to emulate—certainly I did and other people did, too,” Lunney continued. “We had a chance to do some of this stuff that looked almost magic. We didn’t have leadership courses or anything like that. We had leadership examples flowing all the way through this entire organization. We were immersed in leadership models and examples, and we learned from it. Most of the people who did well said, ‘I want to be like that guy. I want to be able to do what he does. He’s always able to tell what’s coming and be ready for it.’”

Gene Kranz was certainly one of the most well-known flight directors of them all. Kranz’s fame was due in no small part to his trademark crew cut; the familiar vests he wore during missions; his autobiography, Failure Is Not an Option; and his portrayal in the blockbuster movie Apollo 13 by actor Ed Harris. Early in his career, Kranz saw the qualities of his contemporaries at the flight director’s console and tried to incorporate the best of each into his own manner—Kraft, he said, was utterly brilliant and became a gifted leader; Hodge was a great listener who had flight-test experience; and Lunney was ahead of everything he ever did.

Kranz never trusted his memory, so he became a fanatical note taker. The data books he developed became indispensable parts of that preparation, having gone through every schematic in the entire spacecraft, every mission rule, every flight plan, everything. Terrified that he might somehow misplace one of the books, he placed pictures cut out of Sports Illustrated on the outside of the blinder so that people would know immediately that it was his. “Basically, I just relied on organization, personal checklists, and training so that I had my mind made up as to what I would do in the first sixty, ninety seconds of a crisis,” Kranz said. “There were some guys like Lunney who could wing it. He was absolutely gifted. Kraft could always find his way through to an answer by asking the right questions, and he already almost always knew the answer. He was just trying to get people to agree with him.”

Another skill that Kranz worked to develop was the ability to listen to his troops, like a quarterback running the two-minute drill. The flight director’s only consumable, he knew, was time, and under no circumstances could any controller afford to run out the clock. And not only would Kranz listen to what the controllers were telling him, he would listen to the tone of their voice, the inflection of how they were saying it. As time went on, trust developed. “There were many times when the controllers would take a direction and wouldn’t even bother to tell me, because they had confidence I would support them,” Kranz said. “This is, I think, very critical when you’re in time-critical situations. It was a question of getting to know the people, and more so, having an intense feeling for the challenges they had when they were trying to give you answers.”

The beauty of the control room, Kranz continued, was that issues were always black and white. There was no gray—calls were either go or no go. Maybe was not good enough. Flight directors had to trust their controllers, and the controllers had to trust their flight directors to do exactly the right thing at exactly the right moment. It was a bond forged in countless hours of simulations and actual missions. Building trust in the ranks meant knowing the strengths and weaknesses of each, and some had more of one than the other. “There were some people who were very good, and there were some people that were not very good at all, but they were still good team players,” Kranz continued. “So you had to work extra hard with them, and a couple of them on my team were really a challenge. If I had John Aaron, I could get an answer in ten seconds. If I had another guy, it’d be three or four minutes. Basically, you had to develop that kind of relationship with them.”

The thing that stuck out about Kranz to control officer Hal Loden was his bearing in and around the MOCR. He had this air, the perfect leader who had a knack of getting people to perform above and beyond their capabilities. As one memory after another came back to Loden, he began to tear up. “He was one of a kind,” Loden said, strong emotion tinting every word. “There could not have been a stronger task master. He’s like Glynn. He knew the system as well as you did, and in some cases, probably better than you did. He was what I would call the ultimate flight director. There’s nobody who could touch him when it came to getting the job done. He commanded the utmost in respect from everybody, I believe. He certainly did from me.”

Not everyone took to Kranz in the end, but that much could have been said of virtually anybody in any walk of life, in any position of authority. Lop off the scores of those who all but worshipped the man as well as those of the handful who did not care for Kranz in the least, and what remained was probably the best indicator of the kind of man and flight director he actually happened to be.

Charles L. Stough, Tommy W. Holloway, William M. Anderson, Ted A. Guillory, John W. O’Neill, Spencer H. Gardner, Turnage R. Lindsey, Elvin B. Pippert, Raymond G. Zedakar, John H. Covington, and R. R. Cain all worked the flight activities officer (FAO) console to the right of the flight director’s console. It was located there because Glynn Lunney wanted it that way.

Tommy Holloway never had any grand vision of going to work in the space program before he landed there in February 1963, and the FAO’s responsibilities were basically an extension of the planning he did before a mission. He worked on flight plans and crew schedules, and backup plans for things such as cutting a flight short in case something went wrong. Another job was procedures development and putting together the crew’s Flight Data File—the books of checklists and cue cards carried on board the Command Module weighed a total of 110 pounds, and there were thirty-five pounds of books inside the Lunar Module. If the plans needed any updating during a flight, Holloway would take care of it.

During the first several flights of the Gemini program, the FAO position was part of the Flight Crew Operations Directorate, and in that realm, astronauts were king. The problem was that the astronauts had not been immersed in the kinds of planning Holloway had done and sometimes came into the training flow late due to their other responsibilities. Lunney’s debut as lead flight director came during Gemini 10 in mid-July 1966, and when too much fuel was used while maneuvering into position with the Agena docking target, it had been Holloway who had worked on those contingency plans. Lunney wanted him close by during the flight, and from that day forward, the FAO was in the front room. “Glynn Lunney was really instrumental in getting that changed and getting the flight activities officer put in the front room,” Holloway said. “In my view, and of course I’m biased on the subject, that was a master stroke.”

Finally, the last console on the third row belonged to the network controller, who was responsible for the worldwide series of ground stations. George D. Ojalehto, John A. Monkvic, Ernest L. Randall, George M. Egan, Douglass R. Wilson, Lawrence D. “Larry” Meyer, David A. Young, Ronald L. DeCosmo, Charles M. Horstman, Earl Carr, Robert Gonzales, Joseph R. Vice, Fred H. Wrinkle, Walter Soetaert, Julius M. “Julie” Conditt, Thomas W. Sheehan, and Donald H. Baerd worked Apollo from this position. Richard J. Stachurski was there, too, on assignment from the U.S. Air Force. Born and raised in Queens, New York, Stachurski went to high school in Brooklyn—within walking distance of the famed Ebbets Field, home of the Dodgers, although he was a die-hard Yankees fan—and college for the first time in the Bronx. With a degree in history and after a stint in the Reserve Officers Training Corps, he wound up in the air force. “I went in search of adventure, and it found me,” Stachurski said. “It was just an enormous set of quirks and coincidences. I came away from the whole thing with the feeling that if you ever think you’re in control of your life, forget it. It doesn’t work that way.”

It was in 1965 that he got a notice to report to Houston for an interview. What in the world did NASA need with a history major? Stationed at the time at Ellsworth Air Force Base just outside Rapid City, South Dakota, it was a heck of a lot warmer down in Texas, so Stachurski figured, why not? Surely, somebody would come to their senses and realize that this had all been some sort of mistake, but maybe not before he could take a couple of days’ worth of vacation.

Six years later, Stachurski was still in Houston.

Henry E. “Pete” Clements was the air force lieutenant colonel who had proposed the loan of 128 officers to train for that military branch’s manned spaceflight program—which never actually came to fruition—while at the same time supporting NASA’s efforts during its early manpower crunch. That was how Stachurski had made it to Houston in the first place. “Henry was quirky, to say the least,” Stachurski remembered. “Henry would refer to himself in the third person. He would say things like, ‘You may come in now. Henry is prepared to speak with you.’ The guy was a real character.” When Stachurski asked Clements how he had been selected for duty in Houston, the answer was direct and to the point. “He said to me, ‘Well, I thought it would be interesting to see how a liberal arts puke made out in this environment,’” Stachurski continued. “Coming from him, you can believe every word of that. That’s the kind of person he was. He thought that would be funny, and I’m glad he did.”

Initially, he was put in operations scheduling before being moved over to the network console. He was on duty 16 July 1969 as Apollo 11 lifted off. “We were responsible for seventeen tracking stations around the world, eight aircraft, four ships, and all communications that connected them,” Stachurski said. “Everything on the ground belonged to us. We were plumbers. Our job was to keep the circuits up and functioning throughout the mission.” He was amazed to have such an opportunity, working as prime network controller on mankind’s first lunar landing. He was an air force officer, and a history major on top of that. “My sense was even stranger than that,” Stachurski said. “What the hell is a history major doing sitting here in the middle of all of these astrophysics and engineering and whatever guys? I was hustling all the time to make sure I understood what I had to understand.”

Tradition dictated that a plaque for each mission be hung in the MOCR following its successful conclusion. After Apollo 11, that duty fell to Stachurski. “I damn near fell off the ladder,” he joked. “It was a priceless adventure. And it was scary at the time, because I was feeling a little insecure.”

After leaving Houston in 1971, Stachurski headed to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio where he helped develop some of the first remotely flown drones. Over the course of his twenty-six-year career in the military, he also served as deputy program director for the Ground Launched Cruise Missile (GLCM) development program and later served as commander of a GLCM wing in Sicily. Stachurski had, after all, gone in search of adventure.

Finally, the fourth row in the room was staffed by the public affairs officer, as well as upper-level management and officials from the Department of Defense. The fourth row became Chris Kraft’s perch once he left his flight director’s console midway through the Gemini program. He was there for consultation, and no longer in direct control of the flights.

That was a job he left up to the first three rows.

As capable as those who worked the front room were, their success would not have been possible without the Staff Support Rooms (SSRs) that lined the opposite side of the hallway just outside the door to the left of the MOCR. The position was an outgrowth of Kranz’s time in the air force, when he used a Strategic Air Command (SAC) hotline as a B-52 flight test engineer to work out solutions to problems he encountered. Following the fiasco that was the launch of Mercury-Redstone 1 on 21 November 1960—in which it lifted just four inches off the pad and jettisoned its escape tower—Kranz convinced Chris Kraft to set up a hotline to McDonnell Aircraft Corporation and get a couple of engineers assigned to help in the event of the anomalies that were sure to come. By the end of Mercury, the position had been formalized to provide rapid and direct communication with the design and test teams.

The duty of the SSR was just that—support, and in essence, making smart people smarter. “It was a matter of having specialists in the Staff Support Room,” said John R. “Jack” Garman, who staked his claim to fame as an SSR legend during the dicey computer alarms that plagued the moon landing of Apollo 11. “The guys in the MOCR weren’t expected to know everything that the guys in the Staff Support Rooms knew. If you viewed it hierarchically in terms of knowledge, the further down you went, the more knowledge you had.”

Bob Carlton, for instance, had all kinds of support during Apollo 11 as he worked the control console in the MOCR—Robert S. “Bob” Nance Jr. watched over the ascent and descent engines and the mechanical workings of the Reaction Control System; William E. “Bill” Sturm was an employee of the Philco Corporation who was responsible for the Attitude Control System; and John L. Nelson took care of the Primary Guidance and Navigation System. Quite often, the SSR would spot an issue before the operator in the front room did and would bring it to his attention. That was the way it was supposed to work; the front room had responsibility for every system, while each person in the SSR focused on just one or two and could therefore concentrate on them more in depth. “You can’t hardly talk about the MOCR without talking about the SSR, in my opinion,” Carlton said. “The SSR monitored my systems at all times, and if I asked them a question, I instantly got an answer. If the flight director asked me a question, most generally, if I kind of stumbled a minute, the SSR would come in. I didn’t even have to ask him. He was listening to the flight director.”

A good many flight controllers began their careers in the SSR before moving over to the front-room MOCR, but others were content to stay put. Ken Young grew up in MPAD but began FIDO training late in 1963, before choosing to stick with the planning group full time. Rather than riding a console and going through an endless training cycle for the next few years, Young instead supported the Trench’s navigation and rendezvous efforts from the SSR. “MPAD just appealed to my planning nature,” Young said. “We started on most missions three to four to five years before we actually flew them. Of course, we did all kinds of modifications along the way when certain things didn’t work out. I enjoyed that more than sitting on the console and training procedures, which of course are highly important, and all this rapid real-time decision-making stuff. Not that I couldn’t make it. I just didn’t want to spend endless hours in the control center doing the procedures stuff.”

The front and back rooms were a formidable partnership, and one that was strengthened by the simulation team located in a windowed area to the right front of the MOCR. Flight controllers and the sim team formed the perfect example of a love-hate relationship, in that while training exposed many a flaw and embarrassed many an operator over the years, it was fully understood that preparing in such a brutal manner was an absolute critical necessity. The mistakes themselves that were made in training were bad enough, but then they were discussed at length in front of God and everybody once the sessions were completed. Talk about pressure; it was the sim debriefs that derailed many a prospective flight controller. Own up to an error, go over it honestly, and folks were usually good to go unless the gaffes continued to pile up. Those who continually tried to bluff their way out of a misstep were almost always gone as quickly as Chris Kraft could shove them through the closest available door.

“You had a group of people there who either trusted you or they didn’t,” said John Aaron. “They were not very politically correct about what their concerns were. If you weren’t making the grade, if you screwed something up, you got razzed about it. We had confessional every time we made a training run. We would start out at the left-hand front row and all the consoles had to report what they did, why they did it, and whether it turned out to be the right thing to do or the wrong thing to do.” After the MOCR operators consulted among themselves, it was the sim team’s turn and that is when things tended to get really ugly. “Nobody was able to bluff in that room,” Aaron continued. “It was like a poker game. Everybody’s cards were face up. You couldn’t bluff, and you surely didn’t want to get caught bluffing.”

Harold G. “Hal” Miller reported to Langley Research Center on 7 July 1959, after turning down a better offer and accepting $5,430 a year from NASA. He joined the Simulation Task Group and stayed in Virginia through M. Scott Carpenter’s Mercury flight before heading to Houston. Staying with the sim group until leaving the agency in August 1970, the native of Vanleer, Tennessee, knew the qualities of a good flight controller as well as anyone. He had seen it all.

First, good flight controllers were very quick to think on their feet. They would have made good debaters, Miller added.

Second, although intelligence and great memory were clearly important, there was more to the job than just being smart. Check back to the first quality to begin understanding why. “You could take some really smart people and they would wash out in a heartbeat,” Miller said. “I would’ve never made a flight controller. I don’t think on my feet fast enough.”

Third, capable MOCR operators were confident, almost to the point of being cocky. Who? The Trench? Cocky? Never!

Fourth, it was important to have a good sense of humor. Most did, because if they did not, the unofficial debriefs at some local watering hole could sometimes get downright wicked. Those who knew what was good for them laughed it off when they went down the wrong path in training, but at the same time, they also made a mental note to never, ever do it again.