5

Merry Christmas from the Moon

It was late in the summer of 1968, and Rod Loe had been called into a big meeting in Chris Kraft’s office. Arnie Aldrich knew what was coming during the gathering, and told Loe that the two of them needed to be there.

Just keep it quiet.

When Loe arrived, it was readily apparent that something important was going down. Frank Borman was there and so were several other movers and shakers in the NASA world. Kraft wasted no time in getting to the point of it all.

Apollo 8 is going the moon in December.

Loe’s mind buzzed for a moment, silently racing through the implications. He had not been expecting the remark. The calendar said it was August, which meant that a December launch was just four months away. There were, in fact, plenty of reasons not to commit to a lunar journey. There had never been a crew shot into orbit by a Saturn V, and the last time an unmanned one had been launched and tested that April, things had not gone very well at all. And even that was putting it mildly. No human being had ever left the earth’s gravitational sphere of influence. Yet here was Kraft, telling his team that Borman and the rest of his crew would be sent that way in four months’ time. There were reservations aplenty, but none that could not be overcome. This was to be on a strict need-to-know only basis, and for the time being, not that many people needed to know what might be on tap for Apollo 8.

The moment was a seminal one in NASA’s history. The agency could meekly back down from John F. Kennedy’s challenge with the excuse that it was too difficult and dangerous, or it could boldly stare down those demons and formulate an audacious plan to send Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders on their way to lunar orbit. NASA did not back down from the monstrous challenge. Instead, NASA opted to spit in the monster’s eye. A lot of time had passed, but the memories of those heady days were as fresh and as powerful as they had ever been for Loe. Remembering Kraft’s meeting, he paused, trying to choose his words and phrases carefully, each one coming out slowly. Loe was getting choked up, genuinely moved.

Loe served as an EECOM throughout the Gemini program, and was eventually bumped up to oversee the second row’s Communications and Life Support Systems group as its section head. Working as “just” an EECOM meant hour after hour at the console, running simulations. On the other hand, being a section head brought with it the responsibilities of managing people and reviewing people and helping people out. Management was all well and good, but it left little time for work in the front room. As a result, Aldrich had been after him for some time to consider moving over to the SPAN room. Loe resisted, because the MOCR was where the action was. In his heart of hearts, Rod Loe was an EECOM and not a manager.

Following the meeting in Kraft’s office, Aldrich and Loe walked back to the Mission Control Center together. Loe was struck hard with a thought. He wanted this flight, and he wanted it badly. He wanted to be a part of its planning and its implementation. There would be almost too many firsts to count. This was going to be the biggest thing in the young history of human spaceflight, and so he made Aldrich a deal. “I can remember walking back over to our building with Arnie, and I remember telling him, ‘You let me be the lead EECOM on Apollo 8, and I’ll go into SPAN, no arguments at all,’” Loe said.

Loe got his wish, and the flight turned out to be everything he hoped it would be. Apollo 8 was tailor-made for the CSM systems folks—it was their mission, he emphasized. After all, it would be their systems that took the three astronauts on their epic journey. That was despite the fact, of course, that those who worked on the first row of the MOCR would always insist that it was a Trench mission, because it was the Trench’s job to establish the trajectory to and from a moving target. In reality, both were correct.

The year 1968 was one in which the world seemed to be coming apart at the seams, but most in the MOCR were too busy to look up from their consoles to notice.

In January, the Tet Offensive served as proof that the situation on the ground in Vietnam was not good and was getting worse. American troops were facing not just a simple band of guerrillas hiding here and there in the bush, but a well-organized and determined enemy. Civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down in April, while presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy—brother of the slain president John F. Kennedy—was murdered in June. Nearly seventeen thousand American military service members were killed in Vietnam that year, by far the greatest yearlong total of the war and a full ten thousand more than were lost just two years later.

Unrest exploded around America. Jerry Mill, who had graduated in 1967 from the University of California at Berkeley, was a member of the simulation team when Apollo 8 flew, and he remembered clearly having to plow through campus demonstrations to get to his physics classes. “When I finally graduated and got a job with NASA, I felt vindicated,” said Mill, who would later alternate between working as a guidance officer in the Trench and in the SSR. “I’ve never been supportive of those kinds of people or that kind of attitude. I always believed in hard work and the United States of America.” In August, full-scale riots broke out during Chicago’s Democratic National Convention.

Mill was not the only one at NASA to be touched by the war. Gerry Griffin’s twin brother, Richard L. “Larry” Griffin, flew 250 U.S. Air Force missions as a forward air controller in Vietnam and in July 1985 became the first commander of the branch’s Second Space Wing. Bill Bucholz, the air force officer involved in Ed Fendell’s faked heart attack episode back during preparations for Gemini 7/6, flew C-123 transports during the conflict.

Richard Stachurski had a friend in the air force who was killed in the conflict. Jack Knight, in training for his debut on Apollo 9 and the telmu console, was an air force brat who lived at one time or another in the Philippines for a year or so; Libya for two and a half years; Washington DC, while his dad did a stint at the Pentagon; Montgomery, Alabama; and San Antonio, Texas. Jack Sr. also served a tour in Vietnam. More than one person who worked in the MOCR got a draft notice. The letter NASA bosses wrote on his behalf requesting a deferment almost made it seem that if it had not been for Mill, the whole country would have gone down in flames.

It seemed very close to doing so any way.

And then there were the Soviets. It was impossible to forget about the bad guys on the other side of the world. The Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962 brought the world to the brink of a nuclear holocaust, and while that scare passed, others remained firmly entrenched. When the Russians established some new high ground in the space race, retro officer John Llewellyn came banging on the door of Glynn Lunney’s home early in the morning and demanding that the both of them go into work right then and there to do something about it. “That was the world we lived in, one that was frightening,” Lunney said. “There was a lot of uncertainty about whether these guys were really going to do something to us. It was a scary time. A lot of people couldn’t do anything about it, but we could, at least in our portion that we were in charge of in the space theater.”

In mid-September 1968, the Russian Zond 5 flew to the moon and back. It was unmanned but did carry a crew of sorts in the form of a couple of Russian tortoises, wine flies, and mealworms. That resulted in the Central Intelligence Agency picking up on talk that the Soviets might follow up by attempting to send cosmonauts to circle the moon before the end of the year. After pulling even during the Gemini program and in many respects ahead, NASA was not about to miss out on yet another first in human spaceflight. Not this time. It was then that the idea came to George M. Low.

Low was born in Austria, immigrated to the United States after Nazi Germany’s 1938 occupation of the country, and then served in the army during World War II. By 1968 Low had risen to the influential role of manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office. He knew that the LM was not ready, but if all went well on the October flight of Apollo 7, why not send a crew to the moon using only the Command and Service Module? The notion was a “shocker,” according to Chris Kraft. The quartet of Low; Kraft; Bob Gilruth, the director of MSC; and Deke Slayton were what Kraft called in his autobiography “an unofficial committee that got together often in Bob’s office to discuss problems, plans, and off-the-wall ideas. Not much happened in Gemini or Apollo that didn’t either originate with us or have our input.”

Once the ball started rolling, it gathered momentum on an almost daily basis. One by one, meetings led to more meetings and others were brought into the highly secretive fold. Kraft felt out Gene Kranz, Aldrich, and Jerry Bostick about Apollo 8’s lunar plans before the end of the year during a meeting on Friday, 9 August. Aldrich was sure right then and there that the CSM was ready to take on just such a challenge. “It seemed to me immediately that we sure could do that, and it would be a great thing to do,” he remembered. “We never did come up with anything in my discipline that said anything different than that.”

Meanwhile, for the first few moments at least, Bostick had the almost overwhelming notion that it was the dumbest idea he ever heard. Although Bostick was on board as well by the time he got back to his office, he knew that there were going to be hurdles to clear. He told Kraft, “That’s a bold move, and we don’t know if we can do it or not. Give us a few hours, and we’ll try to figure it out.”

Bostick needed to figure out the minimum requirements for the Trench—what displays and capabilities the retro, FIDO, and guidance positions had to have. That in turn became a question for the implementers and how much they could actually accomplish in time to get Borman, Lovell, and Anders off the ground and doing laps of the moon. Software was needed from MPAD for implementation in the Real Time Computing Complex. A new processor was being developed to calculate the maneuvers it would take to get the spacecraft and its crew back home. On top of it all, Kraft wanted Bostick to return to the retro console after working most of the Gemini program as a FIDO. “I would like to think that Chris had great trust in me,” said Bostick, who remained the Trench branch chief. “He understood that one of the risks we would be taking was if we had to abort the mission for some reason, and even if we didn’t, we were going to be reentering the earth’s atmosphere at a higher speed than we ever had before. He had enough confidence in me to think, ‘You’re the natural guy to supervise all of that the first time we do it.’”

Bostick was back on the retro console, but he was not technically the position’s lead for the historic flight of Apollo 8. Neither was the larger-than-life John Llewellyn, the section head. Instead, that duty fell to Chuck Deiterich, who would be working his first manned mission. Consider that for a moment—a rookie taking the lead over two of his bosses, one the branch chief and the other his section head. Bostick broke the news to Deiterich; Ed Pavelka, the flight’s lead FIDO; and Charley Parker, who took on the role of lead guidance officer. Pavelka and Parker were heads of their respective sections—Deiterich was not. “Llewellyn was kind of a strong-willed guy,” Deiterich said. “But you could get along with him. He always trusted me. Bostick did the same, or they wouldn’t have selected me to do that. So as far as feeling like I couldn’t say anything or couldn’t tell them what to do, that never occurred to me.”

There was another reason for Deiterich’s relatively easy transition into the leadership role. Once the door of the MOCR closed behind them as they entered, the hierarchy of the first and second rows all but dissolved. There was the flight director and then everybody else. “The administration level in the office environment goes away,” Deiterich said. “When you’re in the control center, you work for the flight director. You don’t work for your branch chief. So, as far as being intimidated because I had my two bosses working for me, I never once thought that what I did or didn’t do would affect my career or my relationship with them when we were back in the office. That just never occurred to me.”

Parker might have been known as “the Fox” for his calm, cool, and calculating demeanor at the Trench’s guidance console, but he could not stifle a chuckle when asked about his response to Bostick’s big news. “My initial reaction was, ‘Awww, man, that is a long step,’” Parker said in his rich Texas tone. “I had a lot of misgivings about it at first.” His primary concern was whether or not the first-floor computing complex could be readied in time with all the necessary programs to compute lunar orbits and returns.

This would not be just a slingshot trip around the moon, either. John P. Mayer, the head of MPAD, and Bill Tindall, a NASA engineer who was the chief of Apollo Data Priority Coordination, figured the flight could go into lunar orbit. “After we got to looking at it and realized we had the capability to do more, we went back with a proposal that said, ‘Hey, we want to go into orbit, map the lunar-landing sites, spend a day in orbit, and then come back,’” Parker recalled. “That was kind of a big surprise to headquarters, and they mulled it over for a while before coming back and saying, ‘Go for it.’” Before he knew it, Parker was involved in planning and flight techniques meetings and farmed out some of the work on console and training requirements to Will Fenner. It was all still very much hush-hush, so Deiterich, Pavelka, and Parker each limited engaging others as much as possible.

Glynn Lunney served as lead flight director for Apollo 7, which was controlled out of the MOCR on the second floor. Although there had been a near mutiny on the part of the crew during that flight, all had gone well with the CSM. Aldrich’s confidence in his machine was nowhere near unfounded—that hurdle to the moon for the next flight had just been cleared. As Lunney was walking out of the second-floor control room following Apollo 7’s splashdown, Cliff Charlesworth took him aside. Charlesworth would be taking the lead as an Apollo 8 flight director, and he broke the news about its flight plan. Lunney’s response was one of stunned disbelief, though the possibilities were probably already going through his mind.

“We’re going to what?!?” he wondered out loud. Lunney came around, and quickly. “Within minutes—minutes—it was like, ‘That’s the best damn idea I’ve ever heard,’” he admitted. “It was like a bolt of energy flowing through this whole team when the idea that we were going to go to the moon on the next flight was decided.” Ever supportive of Low and Kraft, Lunney would eventually wonder why he had not come up with such a bold initiative.

A bolt of energy or not, NASA was in the process of taking a calculated risk with its future. Barely nineteen months had passed since a fire claimed the lives of the Apollo 1 crew, and “go fever” had helped seal its fate. In its rush to the moon, issues were overlooked and three astronauts died as a result. Was the same thing in danger of happening again? The goal of beating the Soviets to the moon was admirable enough, but what might happen if another team of astronauts lost their lives in the process? A successful flight of Apollo 8 would open the gates to a lunar landing, but that success was an awfully big mountain to clear. “It was daring,” Bostick concluded. “A lot of hurdles had to be overcome. I knew it was risky, and we did take risks. Glynn Lunney and I in our old retirement years have sat around and talked about how that was really what we were doing. We were in the risk-management business. We didn’t call it that, because we’d never heard that before. But that’s what it was. We did take risks, but we were never reckless. I didn’t think that on Apollo 8 we were doing anything that was reckless.”

Once he got over his initial shock, Lunney was ready to take the leap of faith. “Here’s the deal,” Lunney said matter-of-factly. “The truth is, if you’re going to go to the moon, sooner or later, you’ve got to go to the moon. Now, you can hunch around and do little things in Earth orbit and so on and so on, but if you want to go to the moon eventually, then eventually, you’ve got to go to the moon.”

It was not until NASA issued a press release on 12 November 1968 that the orbital flight around the moon was officially announced to the public. The flight would depart no earlier than 21 December, so close to Christmas, yet the release insisted that timing of the launch window was “solely dependent” on technical considerations.

Rod Loe was the prime EECOM on Apollo 8, and he worked closely with John Aaron while preparing for the mission. “You couldn’t keep John away,” Loe said. “He was as excited as I was about doing this.” From the time the two of them were told of Apollo 8’s ambitious flight plan until launch, Loe and Aaron spent most every Saturday at MSC and a few Sundays, too, with Anders. Although there was no Lunar Module to pilot, the rookie astronaut was designated the flight’s Lunar Module pilot (LMP). That put him closest to most of the EECOM-related switches near the Command Module’s right-hand couch during launch and reentry. Together, the three of them wrote procedures and mission rules and what-iffed everything they could possibly imagine.

They pictured an oxygen leak in the CSM, and what might be powered down in an attempt to get back home in case of some sort of failure in its power systems. They thought of cobbling together some sort of device to scrub excessive carbon dioxide out of the cabin. The groundwork was being laid for the life-threatening issues Apollo 13 would face in a little more than a year’s time. “The decision was made and we scrambled and got everything together to do it,” Aaron said. “That was the surprise of the century to me, that we were going to step off Apollo 7 and just go to the moon. The Apollo 7 mission demonstrated that the CSM and its systems were ready, but that CSM was launched on a very mature and different booster. But next, we were going to stack men atop that big and relatively new Saturn V on Apollo 8 and go. That was an incredible surprise, and of course, it went like clockwork.”

When Apollo 8 launched on 21 December 1968, less than nine months had passed since the Apollo 6 unmanned test of the Saturn V booster went all kinds of haywire.

If sending a crew to the moon seemed ambitious in the late summer of 1968, doing so on top of a Saturn V might well have been considered downright crazy earlier that year to most outsiders. To Glynn Lunney, however, the gigantic launch vehicle had simply “misbehaved” on its second unmanned test. “It just hiccupped all over the place,” he said. “But the Marshall guys did fixes for it, and they were the kind of fixes that said, ‘Oh, well, that’s going to solve this problem. They’ll go away, so let’s get on it.’ The truth is, if you’re going to light a big Saturn V, which is really a big bomb that you’re trying to control, you might as well get the most out of it.”

One of those Marshall guys was Frank Van Rensselaer, who was assigned the booster systems 1 console at the left end of the Trench for the flight of Apollo 8. Van Rensselaer had not been prime on Apollo 6, but he was for Apollo 8 and he knew exactly what was on the line. Would the launch vehicle perform as it had been designed, and would he be able to perform as he had been trained? For each and every person who ever sat a console in the control room, the latter was the question of all questions. “It was a great concern after seeing what happened on 502,” said Van Rensselaer, referring to Apollo 6 by its Saturn V spacecraft designation. “The more sims we did, the more you realized how many things could go wrong. So you just hoped that you had prepared yourself for the failures you think might happen. You’re trained to think fast. You’re trained to say what you had to say on the loop and then get off. You were trained to know where to go to get help, if you had time to get help. Most of the time during the boost phase, you didn’t have time to get help.”

Apollo 8 was the highlight of many a NASA career for a myriad of reasons, and Van Rensselaer was no different. Knowing what could have gone wrong and seeing what had gone wrong on Apollo 6, Van Rensselaer felt most would have given the first manned lunar mission not much more than a fifty-fifty chance of making it to the moon. “Frankly, I was just praying we could at least get the crew in orbit,” he continued. “We did plenty of simulations on aborts—aborts off the pad, aborts a couple of minutes into the flight, and on all the way into orbit. I think everybody was probably as nervous as they were ever going to be on that flight.”

The only other flight in NASA’s history that could begin to approach Apollo 8 in terms of sheer nerve was STS-1, the 1981 maiden voyage of the Space Shuttle. The stack of the orbiter, External Tank, and twin Solid Rocket Boosters had never been tested together, much less with a couple of living, breathing human beings in the form of astronauts John Young and Robert L. Crippen on board Columbia. “We all knew that if something went wrong in the first two minutes, there was no coming home for those guys,” Van Rensselaer said. “To picture them sitting on top of that thing, at least on Apollo 8, we had a couple of test flights unmanned. One of them didn’t work so well, but we did get them in orbit. No matter what flights we’re talking about, those two stand out for me as the real gutsy ones.”

For all of Van Rensselaer’s concerns—or anyone else’s, for that matter—the candle was lit under Apollo 8’s Saturn V and it left Launch Complex 39, Pad A, at KSC right on time. It was precisely 6:51 a.m. in Houston, and the ascent was described in one of the most beautiful NASA-speak words possible.

Nominal.

Nothing of any consequence, real or imagined, went wrong. Eleven minutes, thirty-five seconds later, Apollo 8 was in Earth orbit. So far, so good. The first two of three major commit points had been achieved—launch and Earth parking orbit—while a third, the trans-lunar coast up to the point of braking into lunar orbit, still remained. Cliff Charlesworth was the lead flight director, and he had overseen a virtually flawless flight. Next came checks of virtually every nook and cranny of the CSM’s systems, making sure that everything was just right. It was. Charlesworth’s Green Team was still on shift two and a half hours after the launch when capcom Michael Collins gave the crew a momentous call—the spacecraft’s systems checked out fine. They were all set for the translunar injection burn of the S-IVB stage.

All right, Apollo 8. You are go for TLI.

For the first time ever, the bonds of Earth orbit were about to be broken. In his extraordinary autobiography, Carrying the Fire, Collins wrote of the moment’s meaning.

A hush fell over mission control. TLI was what made this flight different from the six Mercury, ten Gemini, and one Apollo flights that had preceded it, different from any trip man had ever made in any vehicle. For the first time in history, man was going to propel himself past escape velocity, breaking the clutch of our earth’s gravitational field and coasting into outer space as he had never done before. After TLI there would be three men in the solar system who would have to be counted apart from all the other billions, three who were in a different place, whose motion obeyed different rules, and whose habitat had to be considered a separate planet. The three could examine the earth and the earth could examine them, and each would see each other for the first time. This the people in mission control knew; yet there were no immortal words on the wall proclaiming the fact, only a thin green line, representing Apollo 8 climbing, speeding, vanishing—leaving us stranded behind on this planet, awed by the fact that we humans had finally had an option to stay or to leave—and had chosen to leave.

The actual burn began at 11:41 a.m. in Houston, about half an hour after Collins’s message. The maneuver lasted five minutes and 17.72 seconds, and ten seconds after it was finished, the CSM had been injected into its translunar coast at a speed of more than 6.7 miles per second.

Apollo 8 was on its way.

One last item of business was left, and that was to separate the CSM from the S-IVB third stage thirty minutes after the start of the TLI burn. After spending another twenty minutes photographing the third stage and station keeping, a tiny burn of the Service Module’s Reaction Control System moved the two gently apart from one another—a little too gently, as it turned out.

When the CSM was still too close for comfort from the spent S-IVB, FIDO Jay Greene began preparing for a second and larger burn to get away for good. “It was kind of interesting,” Deiterich remembered. “Borman didn’t like where the S-IVB was. I think they approached to see what the panels looked like or what have you, and when they backed away, he still didn’t like it. Jay computed a midcourse correction, which certainly put us far away from the S-IVB.”

A couple of potentially serious issues cropped up early in the outbound journey. A midcourse correction took place eleven hours into the flight, at 5:50 p.m. in Houston. The flight’s trajectory had been biased off ever so slightly, just so the engine could be tested. While it had been targeted to boost the CSM’s velocity by 24.9 feet per second, the burn instead came up more than four feet per second short of that goal. This was the same engine that Borman, Lovell, and Anders were depending on to get to the moon, into and out of lunar orbit, and then back home again. Less than half a day into the flight, it was showing an anomaly. “I haven’t seen too much written about it, but there was a glitch,” said guidance officer Charley Parker. “The engine had a rough start. It didn’t come up to thrust properly. So now we really had a problem. Are we really going to trust this engine to put us into lunar orbit, knowing that we’re going to have to use that engine to put us into lunar orbit, knowing that we’re going to have to use that engine to come out of orbit? There were some tense times during that period, but the engine people felt like they had it well under control and that we could go ahead. We did, and it worked fine.” Helium left in the fuel lines of the SPS back on the ground caused the small burp in performance, so essentially, the engine was fine, none the worse for wear.

If the balky SPS left some mission controllers with a sinking feeling in the pits of their stomachs, Frank Borman was in far worse shape. All three crew members had been a bit queasy after unstrapping from their couches and beginning to move around the spacious—and downright luxurious, compared to the Gemini capsules in which Borman and Lovell had previously flown—Apollo Command Module. Borman, however, wound up sickest of the three by far. After waking up from a fitful sleep sixteen hours into the mission, Borman had a headache and was stricken with the Big Three in motion sickness—nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The ground knew nothing of the problem until it was mentioned in a downlinked voice tape. “The spookiest moment was when Borman got sick on the way out,” Deiterich said. “We didn’t know if it was radiation sickness or what it was. That kind of got us a little on edge.” The mission pressed on.

The more Borman, Lovell, and Anders traveled away from their home planet, controllers began noticing something they had never seen before during flight. A command would be sent, say, to switch from one antenna to another to get a better signal, and nothing happened right away. A second or two might pass, and then maybe another. Finally, confirmation would come back that the change had been successful. “The signal would come back to Earth, but it was about a three-second delay,” said INCO Joe DeAtkine. “We didn’t use to have that. You had to kind of get used to it as they got further and further away from the earth. The speed of light wasn’t that fast anymore.”

Phil Shaffer was a giant of a man. Standing maybe six and a half feet tall and tipping the scales at close to three hundred pounds or more, Shaffer got tagged as “Jolly Red” by his mates in the Trench and the rest of the MOCR because of his size and what red hair remained around the balding crown of his head.

There was more to Shaffer than just his imposing size, a lot more. To Jerry Bostick, Jolly Red was his deputy branch chief and one of the most exceptional people he ever met. To rookie Bill Boone, who made his debut as a FIDO during the flight of Apollo 7, Shaffer and John Llewellyn had served as his unofficial hosts his first week at NASA in June 1967. The three of them went out for a night on the town at the Singin’ Wheel, a local watering hole in nearby Webster, Texas. The rest is history, what Boone can remember of it. “I was fresh out of school and thought I could drink beer with anybody,” Boone said. “There was no way I was going to dust them. Shaffer piled me in the back of his convertible and proceeded to show me the Gulf Coast at night. I ended up at his place, fertilizing several trees.”

In the control center, Shaffer had the ability to ask questions of Boone that helped guide the young operator to solve problems on his own. Shaffer, Boone continued, spent time with shamans in New Mexico and came to believe in reincarnation and out-of-body experiences. The two of them, he continued, once actually shared such an event. “I could talk hours about him,” Boone said of Shaffer, who died 14 June 2007. “I miss him. I miss him today, and he’s been gone several years. It was just great to pick up the phone, and in about thirty seconds, we’d be right back where we were twenty years ago.”

To Bill Stoval, another freshman controller who made his debut at the FIDO console during the flight of Apollo 10, Shaffer had the amazing ability to manipulate without anyone actually feeling as though he had been manipulated. Stoval joined Shaffer in Mensa, the high IQ society, then promptly dropped right back out again after about a year. They cooked ribs and drank beer together. “He was an incredible man,” Stoval said. “When he became a flight director, he would ride me hard. It pissed me off, because he knew more than I did.”

As brilliant as Shaffer was, press conferences were evidently not his cup of tea—at least not when it came to attempting to explain the transition from the earth’s to the moon’s sphere of gravitational influence to a bunch of dumb reporters. A blip in the computers caused them to calculate a sudden difference of a few miles in the spacecraft’s positioning as it crossed between the two, and as hard as Shaffer tried to get the point across to the press, it was just not working for him. “Never has the gulf between the non-technical journalist and the non-journalistic technician been more apparent,” Michael Collins wrote in Carrying the Fire. “The harder Phil tried to dispel the notion, the more he convinced some of the reporters that the spacecraft actually would jiggle or jump as it passed into the lunar sphere.”

By then, Collins was having himself a jolly good time, snickering over Shaffer’s predicament. “Big as a professional football player, red-faced and sweating, Phil delicately re-examined his tidy equations and patiently explained their logic,” Collins continued. “No sale. Wouldn’t the crew feel a bump as they passed the barrier and become alarmed? How could the spacecraft instantaneously go from one point in the sky to another without the crew feeling it? The rest of us smirked and tittered as poor Phil puffed and labored, and thereafter we tried to discuss the lunar sphere of influence with Phil as often as we could, especially when outsiders where present.”

Collins had so much fun with Shaffer over the incident, he mentioned it during the flight of Apollo 11. As the flight began its long journey back to Earth, capcom Bruce McCandless let the crew know when it had left the moon’s sphere of gravitational influence. Collins could not help himself.

Roger. Is Phil Shaffer down there?

Negative, but we’ve got a highly qualified team on in his stead.

Rog. I wanted to hear him explain it again at the press conference. That’s an old Apollo 8 joke, but tell him the spacecraft gave a little jump as it went through the sphere.

As McCandless began his response, Dave Reed knew exactly what Collins was up to.

Okay, I’ll pass it on to him. Thanks a lot, and Dave Reed is sort of burying his head in his arms right now.

Jerry Bostick and Charley Parker passed time during the outbound coast with a discussion of what might happen during the crossover—well out of earshot of any reporters, quite unlike Shaffer. No one was quite sure exactly when the computers would decide that the Apollo 8 spacecraft had started falling toward the moon, with its gravitational influence greater than that of Earth’s. Across the hall from the MOCR in the Flight Dynamics SSR, Jack Garman got in on a pool that somebody drew up over when the event light would flash. It was high stakes too, at a quarter a pop. “I did not win,” Garman admitted ruefully. Mankind first left the earth’s gravitational dominance at 2:29 p.m. in Houston on 23 December 1968, fifty-five hours and thirty-eight minutes into the flight of Apollo 8. The spacecraft was 176,250 nautical miles out.

8. As famous as the Apollo 11 lunar landing would become just a few months later, many who worked in the MOCR considered Apollo 8 every bit as memorable a moment in their NASA careers. Courtesy NASA.

History does not record who won the SSR pool.

It was the wee early morning hours of Christmas Eve in Houston, and less than five minutes remained before Apollo 8 was supposed to slip around to the far side of the moon.

A lot was about to happen, and nerves were taut in and around the MOCR. Loss of signal (LOS) meant no communications or telemetry until the spacecraft peeked back around to the lunar near side. As if the tension needed to be ratcheted up any more, the lunar orbit insertion (LOI) burn of the SPS engine was slated to take place on the far side. There would be no way of knowing if it had been successful until the signal was once again acquired (AOS). Amid all that, a message from capcom Gerald P. “Jerry” Carr caught Frank Borman off guard.

Apollo 8, Houston. Five minutes LOS, all systems go. Over.

Borman responded like the West Point cadet he once was.

Thank you, Houston. Apollo 8.

Roger, Frank. The custard is in the oven at 350. Over.

If ever an air-to-ground message seemed out of place, that was it. Custard? What custard? Borman came back to Carr the only way he knew how.

No comprendo.

The custard was, figuratively speaking, in the oven and it had been placed there by Borman’s wife, Susan. Although she had at one time or another been sure that the flight would end in disaster, the custard line was her way of putting up a brave front for her husband. He could take care of his business as a world-famous astronaut, while she stayed behind to stand vigil as the ever-supportive wife. “I remember talking with Susan about it,” Carr said. “She said, ‘When I would get excited or overwrought or anxious about something, Frank would say to me, ‘Why don’t you just calm down, go make a custard, and just take it easy?’ So I want you to tell him when you get a chance that the custard’s in the oven at 350.’ I think we caught him completely unawares, because he said, ‘Huh?’ and then thought for a few minutes before he figured out what we were saying. I don’t think he expected to hear that from me.”

Carr remembered Susan Borman’s message, but he had already forgotten all about fellow rookie astronaut Ken Mattingly. Mattingly had been the capcom on flight director Milt Windler’s Maroon Team as Apollo 8 closed in on the moon, and he did not want to miss out on being in the control center for LOS. But miss out he did. “I had finished up and turned it over to Jerry,” Mattingly remembered. “I said, ‘Jerry, I’m going to go get some sleep. Call me an hour before LOS so I can come over and watch.’” It was a simple-enough request, but one easily forgotten in the midst of the momentous events that were unfolding. “Well, Jerry got all excited and forgot to call me,” Mattingly continued with a good-natured chuckle. “When I woke up, the whole world knew they were in lunar orbit. I was really chagrinned.”

What Mattingly missed was a hush that fell over the control room as the seconds ticked down to LOS.

Two minutes.

One minute.

Borman announced that he was starting the onboard recorder, and Carr wished the crew well.

Anders came on the line.

Thanks a lot, troops.

Then Lovell.

We’ll see you on the other side.

And that was it, just before a crackle of static echoed through headsets plugged into MOCR consoles. The signal from Apollo 8 blinked out right on time, at 3:49 a.m. in Houston, sixty-eight hours, fifty-eight minutes, and forty-five seconds into the flight. The LOI burn would not take place for another ten minutes or so. The whole thing was a tad unsettling to Jerry Bostick. “It was obviously a very critical maneuver that they had to perform on the backside of the moon, out of contact with us,” he said. “Everything had to go right, or we would be in a number of bad situations. It was pucker time.” Already, Bostick was sorting out his options on what to do if the burn was too long or too short, or if it had not taken place at all. “It was an unknown, the first time we’d ever done this,” he continued. “There were a number of possible outcomes, some of which were not very pleasant. It was just a time to really be on guard.”

The Black Team was on console for LOS, and with nothing to monitor, flight director Glynn Lunney told his troops that it was as good a time as any to take a break. Take a break? Now? Why not? There was nothing else to do. “Very quickly, I realized that was probably the smartest thing I ever heard, because there’s not a damn thing we could do,” Bostick said. “If we weren’t prepared for the consequences, there wasn’t anything I could do in the next ten minutes that was going to get me prepared, except go to the bathroom.”

Retro officer Chuck Deiterich had virtually the same initial reaction as Bostick to Lunney’s suggestion. “As soon as we had LOS, Lunney said the funniest thing that I’ll never forget,” Deiterich remembered. “He said, ‘Take a break and we’ll see you back here before acquisition of signal.’ I thought, ‘Now, that’s really interesting.’ There was absolutely nothing we could do. It was just that walking away when they getting ready to do the first lunar insertion burn seemed kind of strange.” That was Lunney, in a nutshell. “Lunney knew all our jobs very well,” Deiterich continued. “He would let you do your own job and he would never try to second-guess you. He was probably one of the best flight directors there ever was.”

Ten minutes after Apollo 8 disappeared, the SPS came to life to slow the spacecraft to its orbital velocity of 5,458 feet per second. It burned for four minutes, 6.9 seconds and put the flight into an elliptical orbit that was later refined to a circular one of just sixty nautical miles in altitude above the surface of the moon. Back on Earth in Houston, the MOCR was holding its collective breath. Two clocks were set up in the control room—one that took into account an anomaly, the other a nominal timeline. If the burn had not taken place, the spacecraft would arrive back in range some two minutes before the expected time of acquisition, still speeding along in its free-return trajectory. “Waiting was something we had become used to, but this wait had a distinct edge to it,” Lunney wrote in From the Trench of Mission Control to the Craters of the Moon. “Most of the flight controllers sat quietly, eyes on the two clocks listening and probably offering a prayer. In due course, the first clock reached zero and there was no communication from the ship. The second clock continued to count, reached zero and almost at the same time, the crew reported that the spacecraft was in lunar orbit.”

Carr began his calls to the crew early, in case something had gone wrong.

Apollo 8, Houston. Over.

The same thing, repeated time after time.

Apollo 8, Houston. Over.

Apollo 8, Houston. Over.

Nearly thirty-six minutes after the MOCR had last heard from the crew, public affairs officer John E. McLeaish, handling commentary from the control room, excitedly reported:

We got it! We got it! Apollo 8 is now in lunar orbit! There is a cheer in this room! This is Apollo control, Houston, switching now to the voice of Jim Lovell.

And there was Lovell.

Go ahead, Houston. Apollo 8. Our orbit—169.1 by 60.5, 169.1 by 60.5.

Carr welcomed his fellow astronauts back into contact with the rest of humanity.

Apollo 8, this is Houston. Roger, 169.1 by 60.5. Good to hear your voice.

At the flight director’s console, Glynn Lunney could not suppress a grin. “It was lunar orbit on Christmas Eve 1968,” he wrote. “Playing to an American audience, which was overdue for a reason to celebrate, it choked up all of us. Misty eyes, nods all around, and touches on the shoulders and backs were the shared signs of a decade of work together by the MCC team.” Sy Liebergot, training on the EECOM console, stood up during the celebration and made a rather distinct announcement. “I was excited,” Liebergot said. “That little booger came right around from the backside of the moon after the orbit insertion burn, right to the second. I just leaped to my feet and screamed, ‘The Russians suck!’ I think everybody agreed with me.”

The first television transmission from lunar orbit began a little more than two hours later, at 6:31 a.m. in Houston. Almost as soon as it began, the faraway astronauts began calling off craters that had been named in honor of their NASA brethren.

Brand.

Carr.

Mueller.

Bassett.

See.

Their own craters—Borman, Anders, and Lovell—came into view. After that, Anders continued the running commentary.

Okay, we are coming up on the crater Collins.

Carr, who already had his crater, asked about one that was just passing out of the frame of the television picture.

What crater is that that’s just going off?

Anders came back.

That’s some small impact crater.

Okay.

We’ll call it John Aaron’s.

Okay.

If he’ll keep looking at the systems anyway.

He just quit looking.

Aaron never forgot the surprise of hearing his name called over the air-to-ground loop. “On the way out there, there were a couple of problems with one of our coolant systems pieces of hardware,” Aaron remembered. “I had made some recommendations to the crew about what to do about it and so forth, and it kind of stuck in their minds because they knew who the EECOM was on the ground. So they started naming craters after people, and all of a sudden, they named one after me, an EECOM. I mean, I wasn’t in management at NASA. I was totally shocked that they would remember me, to name a crater after me.”

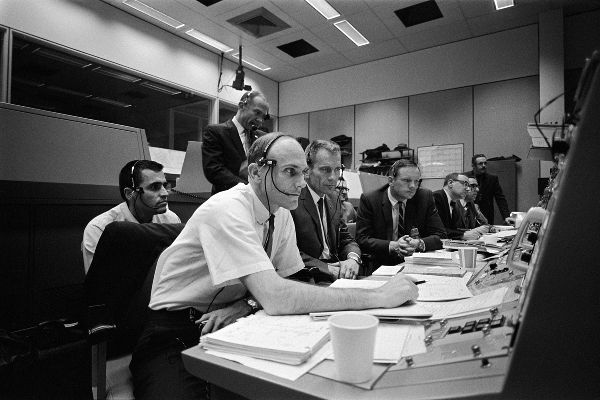

9. Capcom Ken Mattingly (foreground) listens intently to the memorable Christmas Eve broadcast. Surrounding him are fellow astronauts Jack Schmitt (seated behind Mattingly), Buzz Aldrin (standing), Deke Slayton, and Neil Armstrong. Courtesy NASA.

Aaron had not seen anything yet. Apollo 8’s second television broadcast from the moon, which started at 2:34 p.m. on Christmas Eve in Houston, some sixteen hours after arriving in lunar orbit. It was estimated that one billion people in sixty-four countries saw or heard the live broadcast, with another thirty countries added later the same day with a delayed broadcast. By contrast, “only” about 600 million were said to have seen or heard the Apollo 11 moon landing.

The crew began its banter with capcom Ken Mattingly by describing both the moon’s surface and the “foreboding expanse of blackness,” as Anders described the sky around it. When the almost half-hour program was nearing its conclusion, the Sea of Tranquility came into the grainy black-and-white view. Years after the fact, the reading Anders began moments later would still send chills through those who had worked in the MOCR during the flight.

We are now approaching lunar sunrise, and for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you.

Anders continued, reading the first four verses of the King James Bible’s book of Genesis.

In the beginning, God created the Heaven and the Earth. And the Earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, “Let there be light” and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good, and God divided the light from the darkness.

Lovell then read the next four verses.

And God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. And God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters. And let it divide the waters from the waters.” And God made the firmament and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament. And it was so. And God called the firmament heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day.

Borman took over and concluded with verses nine and ten.

And God said, “Let the waters under the Heaven be gathered together into one place, and let the dry land appear.” And it was so. And God called the dry land Earth, and the gathering together of the waters, called He seas. And God saw that it was good.

Flying in space for the second and final time, Borman ended the broadcast with a dramatic flourish.

And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.

That was the moment when the magnitude of what he had just helped accomplish hit John Aaron. The goal all along had been to go to the moon to learn about the moon, and while that did in fact happen during the flight, it also brought back stunningly dramatic images of the earth rising over the lunar landscape—Earthrise. Never before had a single series of photographs captured all of humanity with such clarity, giving him an entirely new perspective on his home planet. For Aaron and so many others in the MOCR that day, the Genesis reading was the perfect capstone for what had to that point been nearly a perfect flight. “They came around the moon and started reading from Genesis, ‘In the beginning, God created Heaven and Earth.’ Just saying it, talking to you, sent cold chills around me,” Aaron said. “Remember, that was on Christmas Eve. I don’t believe there was anybody in that room who knew that was going to happen.”

This is how strongly the moment touched the EECOM. “It was the most overwhelming thing that has ever happened to me in my life, just because it was not only a surprise, it was so appropriate.” For a brief second, Aaron appeared to be on the verge of losing control of his emotions. Quickly, though, he collected himself before concluding, “I don’t know if it had the same kind of impact on other controllers that it had on me, but I suspect it did.”

There was no suspecting to it, really. The audaciousness of the flight plan in general, and the reading from Genesis in particular, had all kinds of lasting impact on the people around Aaron in the MOCR. “The word ‘incredible’ is not even adequate,” said Jerry Bostick. “I had two feelings, I guess. I thought, ‘My God, I’m proud to be an American. We’ve got American astronauts circling the moon. That’s just amazing.’ The other thought was that it was Christmas, and they started reading from the Bible. I just thought, ‘It doesn’t get any better than this.’ It was very moving. It’s something I’ll never forget.”

All that was left now was to disappear behind the moon one last time, and while on the far side, to perform the trans-earth injection burn to get out of lunar orbit and start the return journey. Beginning at just past midnight on Christmas Day and lasting three minutes and 23.7 seconds, flight director Milt Windler’s Maroon Team was on console for the burn that hurtled the spacecraft Earthward at a velocity of 8,842 feet per second. Apollo 8 had been in lunar orbit for twenty hours, ten minutes, and thirteen seconds, for a total of ten laps around the moon.

Ken Mattingly was once again on duty as capcom. After giving the crew a handful of cursory calls, he finally got a response from Lovell.

Houston, Apollo 8, over.

Hello, Apollo 8. Loud and clear.

Roger. Please be informed there is a Santa Claus.

It was 12:25 a.m. in Houston. “The next thing, I saw the spacecraft come around the hill,” Aaron said. “When it came around from behind the moon, they were on their way home.” Twenty minutes later, Deke Slayton was on the horn to the returning astronauts.

Good morning, Apollo 8, Deke here. I just would like to wish you all a very merry Christmas on behalf of everyone in the control center, and I’m sure everyone around the world. None of us ever expect to have a better Christmas present than this one. Hope you get a good night’s sleep from here on and enjoy your Christmas dinner tomorrow, and look forward to seeing you in Hawaii on the twenty-eighth.

Borman took the mic, sounding positively excited to hear Slayton’s voice.

Okay, Leader. We’ll see you there. That was a very, very nice ride, that last one. This engine is the smoothest one.

Yeah, we gathered that. Outstanding job all the way around.

Borman then paid the MOCR a compliment, almost like a triumphant NASCAR driver thanking “the boys back in the shop” after a victory.

Thank everybody on the ground for us. It’s pretty clear we wouldn’t be anywhere if we didn’t have them helping us out here.

Moments later, Anders took the opportunity to get in a dig on the MOCR’s boss of all bosses.

Even Mr. Kraft does something right once in a while.

Slayton, grinning, gave his reply.

He got tired of waiting for you to talk and went home.

The good-natured banter was not over. Mattingly briefly turned the capcom mic over to fellow rookie astronaut Harrison H. “Jack” Schmitt. “Typhoid Jack,” as Schmitt called himself, read up a “gotcha” poem to the crew. The parody of “Twas the Night before Christmas” by Clement C. Moore was one of several written by MPAD’s Ken Young, who was in one of the back-room SSRs when Schmitt took the floor. Young wrote several different parodies of Moore’s famous poem over the years—“A Visit from St. Kranz” seemed a particular favorite—but the Apollo 8 version was the only one that ever made it onto the air-to-ground loop. He was taken completely by surprise. “Yeah, it was a thrill,” Young said. “Everyone in MPAD was proud of their parts on all these great flights. And as MPAD poet laureate—several threatened to string me up!—I just tried to get some props for the best group of rocket scientists in NASA. We were a fun bunch!”

Schmitt began reading.

Twas the night before Christmas and way out in space,

the Apollo 8 crew had just won the moon race.

The headsets were hung by the consoles with care,

in hopes that Chris Kraft soon would be there.

Frank Borman was nestled all snug in his bed,

while visions of REFSMMATs danced in his head;

and Jim Lovell, in his couch, and Anders, in the bay,

were racking their brains over a computer display.

When out of the DSKY, there rose such a clatter,

Frank sprang from his bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the sextant he flew like a flash,

to make sure they weren’t going to crash.

The light on the breast of the moon’s jagged crust,

gave a luster of green cheese to the gray lunar dust.

When what to his wondering eyes should appear,

but a Burma Shave sign saying, “Kilroy was here.”

The line about the Burma Shave sign and Kilroy brought down the house. A hearty round of laughter could be heard on the air-to-ground loop as Schmitt continued.

But Frank was no fool, he knew pretty quick

that they had been first; This must be a trick.

More rapid than rockets, his curses they came.

He turned to his crewmen and called them a name.

Now Lovell, now Anders, now don’t think I’d fall,

for that old joke you’ve written up on the wall.

They spoke not a word, but grinning like elves,

and laughed at their joke in spite of themselves.

Frank sprang to his couch, to the ship gave a thrust,

and away they all flew past the gray lunar dust.

But we heard them explain ere they flew ’round the moon,

Merry Christmas to Earth; we’ll be back there real soon.

Apollo 8 slammed back in the earth’s atmosphere at 9:37 a.m. in Houston on 27 December, traveling at a speed of nearly seven miles per second. Fourteen minutes later, the spacecraft nestled into the waters of the Pacific Ocean in the local predawn hours. After a planned wait for daylight, the crew was helicoptered to the awaiting deck of the USS Yorktown.

Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders were home. The MOCR had done it.

One right after the other, many in the MOCR agreed that Apollo 8 was the highlight of their careers, even more so than Apollo 11 or maybe even Apollo 13. It represented the light at the end of the tunnel. NASA could, in fact, land a man on the moon by the end of the decade. To Jerry Bostick, the cake was baked at Christmas of 1968 with the flight of Apollo 8. The icing was added less than seven months later during Apollo 11.

John Aaron concluded that Apollo 8 was every bit as unlikely an adventure as the famous early 1800s expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. “Lewis and Clark hauled off on a mission to go across the whole country, didn’t know where they were going, and wound up pulling it off,” Aaron said. “They only lost one man, due to ruptured appendicitis. It was just like that was meant to be.” That was the distant past, but Apollo 8 represented that same spirit nearly two centuries later. “A lot of things could’ve happened to us on Apollo 8, because it was hanging out,” he continued. “It was hanging out.”

Then there was Rod Loe. “It’s the only mission I can ever remember having tears in my eyes, sitting on the console that night when they came around the moon and they started reading from the Bible,” he said. “That was really touching.”

Again, the emotion was thick in Loe’s voice. It took not even a second, and he was back in 1968, about to attend the splashdown party for Apollo 8 at the nearby Flintlock Inn. He and Aaron took their time before heading to the bar upstairs, and somebody eventually asked why they had not yet made their way to the festivities. His answer was simple.

We’re standing here, just proud to be Americans.

“That’s the way I felt,” Loe added. “I really felt like we had won.”