6

Dress Rehearsals

The new-and-improved Command and Service Module worked well during its first two manned flights in late 1968, and the Saturn V launch vehicle performed flawlessly during the launch of Apollo 8. It was time to see what the Lunar Module could do.

The LM was so bizarre in appearance, its boxy ascent stage and antenna combined with the gold insulation and four spindly legs actually came across as quite beautiful. This was a flying machine unlike any other, designed exclusively for use in space where it was afterward discarded, never to be returned back to the ground. There would be no museum exhibits for the Apollo 9 LM, Spider, or for its Apollo 10 counterpart, Snoopy—which along with the same flight’s Charlie Brown CSM were the very best call signs ever for an American space mission.

Columbia and Eagle were certainly more proper, more eloquently grand names. But Charlie Brown and Snoopy—named after the two main characters in the American comic strip Peanuts—were in the right context every bit as appropriate. Charlie Brown was always the underdog, just as NASA had been during the early days of the space race with the Soviet Union. Snoopy on the other hand was the highly intelligent, intuitive creature who could overcome any obstacle—such as being a dog—to accomplish any goal, again just like NASA as it erased the Russians’ lead and raced headlong toward the moon.

The Apollo 9 test went no further than Earth orbit, while Apollo 10 ventured to within a handful of hair-raising miles of the moon’s surface. They were bookended by the two most famous missions in the history of human spaceflight. The flights became mere footnotes, and that is unfortunate, because without a shakedown of the Lunar Module, there could not have been a lunar landing on Apollo 11 or any other mission for that matter.

Plans called for Apollo 9 CDR Jim McDivitt and rookie LMP Russell L. “Rusty” Schweickart to take the Lunar Module out for its first manned spin, with CMP Dave Scott staying behind to mind the CSM. McDivitt, in particular, was a favorite of Gene Kranz, the mission’s lead flight director. All but a war had been fought over control of crew procedures between those in the MOCR and Deke Slayton, the head of the astronaut office. “My guys studied the systems from the ground up,” Kranz began. “We built the schematics. We’d write the mission rules, mission strategy. So we had this argument going on between the two players. It was so petty that Slayton would never give a flight set of procedures to the controllers on console. So we were always wondering what the crew was carrying on board the spacecraft.” It was no small feat for McDivitt to end the stalemate, what with Slayton being his boss and all. “McDivitt looked at this and said, ‘This is ridiculous!’” Kranz continued. “So McDivitt got a hold of his crew procedures people, broke ranks with Slayton, and made sure that every controller, including the flight director, had a set of the onboard crew procedures. And from that day on, we never had a problem.”

Kranz led the unmanned test of the LM on Apollo 5 in January 1968, and with the experience of Apollo 9 in his back pocket, he felt it would give him a leg up on getting the plumb assignment of all plumb assignments—directing the first lunar descent and landing. Kranz was the boss and he could very well have named himself to the landing, regardless of whether or not he was familiar with the LM. He could have done that, but he did not. Gene Kranz was getting his ducks in a row for the Apollo 11 descent by flying Apollo 9. “Every flight director wanted to do the landing,” Kranz said. “We were all trying to figure out ways to position ourselves so that we’d be the obvious ones chosen. This gave me an opportunity to really come up to speed now with a manned Lunar Module, and with two Lunar Modules under our belt, I not only knew the spacecraft but also knew the mission control teams that work with them to understand the strategy and the use of the system, to be intimately familiar with not only the systems, but the procedures, the mission rules. So you’re really flying missions, but you’re also preparing yourselves for the big one.”

The first five days of the ten-day flight were to include an all-out simulation of a lunar mission—docking and extraction of the LM from its berth in the S-IVB third stage; undocking, followed by tests of the LM’s descent engine, staging, and ascent engine; systems checkouts; burns of the SPS while the two spacecraft were docked; and an extended spacewalk by Schweickart to test his spacesuit and its Personal Life Support System (PLSS) backpack.

Dave Reed was a detail guy, and on Apollo 9, there were more than enough elements to sort through, debate, checklist, and execute. With the obvious exception of Apollo 13, Apollo 9 was the toughest flight of Reed’s career. From his perspective in the Trench, timing was everything. Maneuvers had to go off like clockwork, taking place at just the right time so they could be tracked over various ground stations around the world.

“We had no problems on 9, but boy, we had to work,” said Reed, the flight’s prime FIDO who served on Kranz’s White Team during the flight. “You’re going to do an entire dress rehearsal of everything that has to go on in lunar orbit. It was a real learning curve, and it was a tough one. If I needed to do a burn at Canary, that burn had to come off at Canary. I had to see it and know what the vector was, because the next maneuver would be someplace around Carnarvon. It was bang, bang, bang. If a slip took place, you could be off-range. You may not have what you need to get the job done the way you want to get it done. It was dicey, in that we really needed to stay on schedule.”

Techniques for initializing the LM’s Primary Guidance and Navigation System (PGNS, pronounced “pings” in NASA-speak) and its backup Abort Guidance System (AGS) computers had to be practiced, right along with separation maneuvers, rendezvous, and docking between Gumdrop, the flight’s CSM, and Spider. How would the two react to one another in space? “A lot of people were kind of worried about the dynamics between two inertial guidance systems and which was in control or whether they would try to control each other,” said Gary Renick, who manned the guidance console for the LM initialization, the docked burns of the LM’s descent engine, rendezvous, and SPS burns. “It was like they were fighting each other. One was trying to do one thing, and one was trying to do another thing. The difficulty was just developing all the procedures and techniques to do those things.”

Bob Heselmeyer was as anxious about Apollo 9 as any flight he would fly for reasons similar to Reed’s, and on a personal level as well. The mission was huge. It was the first manned flight of the Lunar Module but it was also his first back in Houston, where he worked on managing the LM’s consumables in the SSR. He was moving up in the world, and if he could continue to progress in his career, the front room was next.

In a sense, Spider and Heselmeyer were a lot alike. He had been out to the tracking stations during Gemini, and he had been through many a simulation in Houston, but he was still an SSR first-timer once the flight got under way on 3 March 1969. Like Heselmeyer, the LM was also unproven. “It’s the first time it’s flying and under fine control,” Heselmeyer said. “You just never know for sure how well all that’s going to work out. You’ve got the guidance system, the propulsion system, the environmental control system, and they all needed to work well enough for that vehicle to get docked again. There wasn’t a backup. The only out was getting docked.”

Heselmeyer wasn’t the only rookie on console in Houston. Jack Knight had been in the SSR for a couple of the unmanned Apollo launch vehicle tests, but Apollo 9 marked the first time he made it out to the front room to man the LM’s telcom console. In doing so, he became the latest in a long line of controllers who uttered a version of what had come to be known as Alan Shepard’s Prayer.

Dear Lord, please don’t let me screw this up.

Of course, a healthy dose of respect for what could go wrong was essential. Those who thought they had everything under control right from the start were the ones you had to watch out for. “That worry was always there for me,” Knight said. “After a while, you have more confidence when you’ve been through a number of flights. I think that’s true of most people. You do have a few people that have excessive self-confidence. Sometimes, those people will think they know more than they do and they’ll go off and make recommendations for things which they don’t really have the background for. They sound like they really know what they’re talking about.”

After the booster controller moved out of his spot on the left end of the Trench, James A. “Jim” Joki was able to set up shop to watch over the Extravehicular Mobility Unit that was to be worn by fellow freshman Rusty Schweickart during an EVA that was scheduled to last more than two hours. The plan called for Schweickart to use handrails to move from Spider to Gumdrop, and then stick his upper torso in the Command Module’s open hatch to simulate a crew rescue. After that, he was to move back to the LM’s porch to do some still photography and television camera work.

Although that was the plan, it was not what actually took place.

Motion sickness had rarely been a problem during the Mercury or Gemini programs, for the simple reason that there had been no room to move around. Compared to those tiny capsules, the Apollo Command Module had room to spare. With that, however, came a price. Room to move also meant having to stave off bouts of nausea—or worse. Soon after the launch of Apollo 9, Dave Scott left his couch to make his way down to the lower equipment bay for a platform alignment. Almost immediately, he knew that he needed to move his head slowly. There was no nausea or vomiting; he just needed to take it easy. He also experienced some spatial disorientation, accompanied by a bit of queasiness for a couple of minutes. For Scott, the feelings quickly passed.

For Schweickart, they did not.

Schweickart took a Marezine tablet three hours before liftoff and another one ninety minutes or so after reaching orbit, but he was still experiencing what the mission report termed a mild dizziness after leaving his couch and turning his head rapidly. He fought the sensation by turning slowly at the waist, instead of just his head. As poorly as he must have felt, he got into his pressure suit to move over to the LM and was sitting quietly in Gumdrop’s lower equipment bay when he suddenly and unexpectedly threw up. Four hours later, he was busy in Spider when it happened again. Evidently, that was enough to get whatever ailed him out of his system. Although he began to feel better and could move about freely, he had no appetite and an aversion to the smell of certain foods. For the first six days of the flight, he consumed only liquids and freeze-dried fruits.

Joki was trying his best not to act like a rookie when he came on duty and discovered what was taking place with Schweickart. “He was really a smart guy,” Joki said. “He could pick up things faster than anybody else. It was just amazing. Unfortunately, we found out that most of the guys get motion sickness. They may be the best test pilots in the world, but they get motion sickness in space. Rusty was still puking his guts up, but we didn’t know that.”

Although it started right on time, at about seventy-three hours into the flight, the EVA was shortened to just thirty-nine minutes. Schweickart briefly tried out the handrails, and also stood on Spider’s porch with his boots secured by foot restraints while Scott did his own stand-up spacewalk from Gumdrop’s open hatch to watch and photograph the whole thing. “Instead of doing a two-hour EVA, we’ll have him put on the equipment and he’ll step out into what they called the ‘golden slippers’ on the porch,” Joki said. “He’ll wave at everybody, we’ll get photographs, they’ll communicate, and we’ll make a two-hour EVA into whatever it took so he didn’t throw up. My first time on console, I got thirty-nine minutes of data. Boy, was I happy as could be.”

With the next day of the flight came the first free flight of the LM and joining back up with Gumdrop. Spider performed almost flawlessly, but at the opposite end of the second row on the control console, Bob Carlton was not exactly satisfied. Rather than being in constant direct sunlight the way it would be on trips to and from the moon, Spider was in shade half the time as it orbited the earth.

Shade.

Sunlight.

Shade.

Sunlight.

Shade.

Sunlight.

The issue of thermal control on the thin-skinned LM was one of Carlton’s biggest concerns—it really drove him up the wall, he said—and the mission of Apollo 9 in Earth orbit did not help him solve much. The PGNS platform was very sensitive to overheating. Gyros did not function properly when they got too cold or too hot. Pressure rose in the LM’s tanks as their temperatures did. What might happen to them during a lunar mission? How was Carlton going to know what the limits of the systems were one way or the other, too hot or too cold?

The issues, of course, were not limited to matters of too hot, too cold, or just right. What might happen if Carlton was losing the LM’s batteries, and trying to get the crew back to Earth? How low could the voltage go and still be able to open the valve for a reentry burn?

It was exactly the kind of information the MOCR would need a year later during the crisis of Apollo 13.

Carlton remembered a thermal expert being brought in to predict what the temperatures were going to be in each of several different systems during just such a flight, and the poor guy was not even close on any of them. “After we flew the first lunar mission, it was laughable,” Carlton said. “I mean, he was so far out of the ballpark, he was embarrassed, just literally embarrassed. I can’t remember the guy’s name now, but I felt sorry for him.” The solution was to “barbeque” the LM by slowly rotating, as if on a spit, just as the CSM had been during the flight of Apollo 8. “The Earth mission for the first Lunar Module, it was not a good parallel,” Carlton concluded. “It helped, but the real gold mine came when we began to go to the moon.”

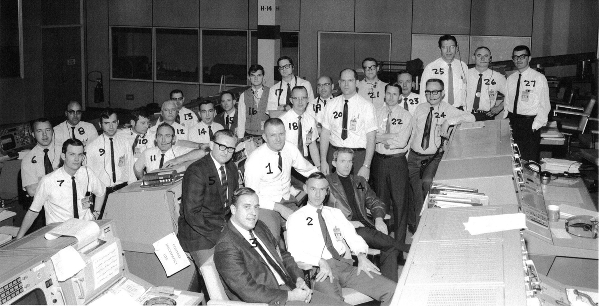

10. Gene Kranz’s White Team during the flight of Apollo 9 included Chuck Lewis (2); Bill Molnar (3); Stu Roosa (4); Dr. Willard Hawkins (5); Dave Reed (6); Earl Thompson (7); Dean Toups (8); John Llewellyn (10); Will Fenner (11); Larry Wafford (12); Arnie Aldrich (13); Charles Dumis (14); Jim Hannigan (15); Bill Strahle (16); Neil Hutchinson (17); Hal Loden (18); Larry Myers (19); Bill Peters (20); Bill Johnson (21); Ernie Randall (22); Jack Riley (23); and Tommy Holloway (24). Numbers 9, 25, 26, and 27 are unidentified. Courtesy NASA.

Dave Reed calculated the burn of the LM’s ascent engine that started the process of closing and braking for re-docking with Gumdrop. After the numbers were read up to the crew, Reed could not hide his surprise when McDivitt called back down to capcom Stuart A. “Stu” Roosa, who had served as a smoke jumper in the Forest Service before joining the air force.

Hey, Smokey. Is Dave Reed smiling?

Roosa glanced at Reed and grinned.

Well, yes. He’s pretty happy, but he’s not going to relax until you’ve finished burning.

Better not.

Reed could not afford to relax just yet, and neither could the rest of the MOCR. McDivitt and Schweickart were out on the ragged edge unlike anyone had ever been before, in a spacecraft without a heat shield. If they could not return to the CSM and dock, they were goners. Ninety-nine hours and two minutes into the flight, Spider and Gumdrop were once again docked. They had been apart for six hours, twenty-two minutes, and fifty seconds.

Years later, long after his career in the MOCR was over, a question arose over the “Is Dave Reed smiling?” quote. To the best of his recollection, it had been McDivitt who asked the lighthearted question. The official transcript released by NASA, however, attributed the line to Schweickart. It was a problem to be solved, and if nothing else, Reed was a detail-oriented problem solver. He emailed both astronauts, and neither could quite put their finger on it. Case closed, right? Not for Dave Reed, not by a long shot.

He had old reel-to-reel tapes of audio from the mission, and they just so happened to include that portion. Not only did he have them converted over to compact disc by MassProductions in Massachusetts, Reed then used his own spectral analysis software to tentatively determine that McDivitt was the speaker. Even that was not good enough. He got in touch with Digisound Mastering out of Melbourne, Australia, convinced them to do a more extensive check, and that result was, at last, good enough for Reed.

It was, once and for all, McDivitt who asked that long-ago question.

So jovial were McDivitt, Scott, and Schweickart after the docking, they had a surprise in store for Chris Kraft nearly five days into the flight. McDivitt first asked if Kraft was in the room, and when told that he was, the veteran astronaut was quick to respond.

Okay. We’ve got a message for him.

Scott and Schweickart joined McDivitt on the loop.

Happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you. Happy birthday, dear Christopher, happy birthday to you.

Kraft’s birthday was actually 28 February, the flight’s original launch date that was delayed due to colds experienced by the crew. Two more choruses planned for their boss, Deke Slayton, and their crew secretary, Charlotte Maltese, did not take place because neither was present for the occasion.

Gumdrop settled into the Atlantic Ocean on 13 March 1969. Another warmup down, one to go.

If Apollo 10 was going to the trouble of simulating a descent to within fifty thousand feet of the lunar surface, why not just attempt to go the rest of the way and land?

11. Lunar Module flight controllers Don Puddy, Bob Carlton, Hal Loden, Jack Craven, and Jim Hannigan (seated on ledge) gathered during landing and recovery operations following the 13 March 1969 splashdown of Apollo 9. Next to them are Ed Fendell and Sy Liebergot (in dark-framed glasses). Larry Canin (back to Liebergot) can be seen chatting with fellow GNC Gary Coen. Visible on the next row up are Richard Stachurski and Ernie Randall. Courtesy NASA.

Really, the question made perfect sense. Glynn Lunney wanted the first lunar landing as badly as the next guy, certainly as much as Gene Kranz, Cliff Charlesworth, or any of the other flight directors active at the time. Lunney was lead flight director on Apollo 10, so maybe this was his in. He and others made their case to Chris Kraft, but Lunney’s mentor was, he said, the “staunchest advocate” of stopping short of the lunar surface. “He wanted us to have the experience of navigating these two vehicles around the moon, knowing where they are and how fast they’re going so that you can get them back together,” Lunney said. “There were unknowns associated with flying so low, close to the lunar surface, because the trajectories would be disturbed by concentrations of mass from whatever hit the moon. It would change the orbit a little bit, and that doesn’t sound like much, but you can’t afford to miss very much when you’re doing what we were doing.”

As was almost always the case, Kraft won the debate. Apollo 10 CDR Tom Stafford and LMP Gene Cernan were going to give Snoopy a shakedown in lunar orbit while CMP John Young stayed behind in Charlie Brown, but that was it. There would be no landing, not this time, for the crew that was NASA’s first in which each member had previous spaceflight experience. All three would also go on to command subsequent Apollo missions—Young and Cernan walked on the moon during the flights of Apollo 16 and 17, respectively, while Stafford flew the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. “In retrospect, Apollo 10 probably could have landed on the moon, but it was a matter of how much do you bite off at a time,” Lunney concluded. “The way it came out, Apollo 10 was absolutely the right thing to do.”

The flight got under way to lunar orbit on 18 May 1969, less than two months before the scheduled launch of Apollo 11. Nearly seventy-six hours later, the SPS was fired for almost six minutes to place Charlie Brown and Snoopy into lunar orbit. Later, as the two spacecraft were preparing for undocking, communications problems between them developed.

Communications was not a new issue. There had been substantial problems during Apollo 9, and now these. The Command, Service, and Lunar Modules all had communications equipment, and controllers in each branch were responsible for their own gear. It was redundant, to say the least. To Bill Peters, who manned the telcom console for both lunar dress rehearsals, a simulation leading up to the mission underscored the issue. “On Apollo 10, I ran the first lunar communications test,” Peters said. “There were about ten communication modes on the LM, as there were on the CSM, and we checked all of them out. That was kind of a detailed, aggravating test for everybody involved, because you’re trying to coordinate ground switching, MCC switching, and spacecraft switching.

Ed Fendell was an assistant flight director during Apollo 10, and it was a job that he loathed. Although he did not know it yet, the comm glitches were going to change the course of his career. “When we went to separate on Apollo 10, the mission rule required that the Command Module and Lunar Module be able to talk to each prior to separation, and they couldn’t,” Fendell said. “They screwed around there for an hour or two, and they finally found out that their switches were out of configuration with each other. Kranz was bouncing off the frickin’ wall.”

A week or so after splashdown of Apollo 9, Fendell was in his office late one afternoon when he got a call from Kranz. “I said, ‘Oh, boy. Here we go,’ because he and I used to have some incredible battles with four-letter words and referring to ancestry,” Fendell admitted and then added as if to spell it out, “We had a different relationship than everybody else.”

Fendell sat down in the flight director’s office, and Kranz began laying out his solution to the comm issue.

We’re going to take every piece of communication equipment and put it under the control of one area. We’re going to form a communications section, and we’re going to form a position in the control center for this communications position.

When Fendell began wondering why Kranz was bringing this up to him, Kranz dropped the hammer.

And you’re going to be in charge.

Fendell could not believe what he was hearing.

What?

Kranz repeated himself.

You’re going to be in charge.

Oh, is that right?

Yeah.

That is not my area of expertise.

It is now.

Fendell’s new staff was going to consist of representatives from various contractors involved in the Command and Lunar Modules, as well as a few others who had never before worked communications. Kranz then gave Fendell his marching orders.

This is your new section. This is your new job. Get out of my office and go do it.

Bill Peters was sold on the idea. “They started planning to make the INCO position its own independent position, and take it away from the Command Module side and take it away from the Lunar Module side,” Peters said. “I think that was a good decision, because there was so much to do on the console anyway.”

If the comm problems were frustrating, the next hiccup was nearly catastrophic. An hour and a half after undocking, Snoopy began a 27.4-second burn that dropped the LM into a descent orbit to test the landing radar for the next flight’s approach into the Sea of Tranquility. Although the closest Stafford and Cernan would get to the surface was 47,400 feet during a low-level pass over Apollo 11’s proposed landing site, Stafford marveled to capcom Charlie Duke about just how near to the surface they seemed to be. Maybe they could attempt a landing after all.

Charlie, it looks like we’re getting so close, all you have to do is put your tail wheel down and we’re there.

Duke was not about to let the pitch go by without a good-natured crack.

Hey, Snoop. Air force guys don’t talk that way.

Cernan excitedly called out the moon’s geological features as they passed by underneath.

Seems like we’re coming up on my side on Taruntius G and I believe Tom’s got his Taruntius H there on his side.

Again, communications were proving to be iffy as the air-to-ground link dropped in and out.

Houston, if you read, we have Secchi on my right. We’re coming into Apollo Ridge. Here’s Apollo Hill, right out the window!

The observations continued until the time came to prepare for staging and rendezvous with Young in Charlie Brown. The ascent was to be flown using Snoopy’s Abort Guidance System in order to simulate an emergency coming up from the lunar surface, but the danger Stafford and Cernan were about to encounter was all too real.

The AGS had a three-position control-mode switch—Auto; Att (short for Attitude) Hold; and Off. In Auto, the guidance system locked the LM onto the CSM’s position and steered it in that direction, while Attitude Hold did just that and held the LM in place. Snoopy was supposed to be in Attitude Hold for its ascent, although a cue card used during the flight showed that the proper mode setting was Auto.

The card was in error. “We traced the problem to a switch setting that was wrong on their checklist,” wrote Chris Kraft in his autobiography. “That was a checklist that got double-checked twice during the rest of Apollo.” Both astronauts later said that the card was not the issue, but they wrote in their autobiographies that Cernan had inadvertently flipped the switch one way and Stafford the other. Regardless of which miscue came into play, it nearly cast Snoopy into the abyss. The LM was left searching for a CSM that was on the other side of the moon and nowhere to be found.

At 102 hours, 44 minutes, and 49 seconds into the flight, the LM started to “wallow off” slowly in yaw, but stopped. The unexpected motion left the LM off thirty degrees in roll, and ten degrees in both pitch and yaw from a normal staging attitude. Twenty-three seconds later, the situation got far worse when the Auto mode began searching for Charlie Brown. Snoopy was pitching about on all three axes, and during the process, staging took place thirty-six miles above the lunar surface.

The now-lighter weight of the vehicle and the AGS’s unlimited error signals only worsened the motion of the spacecraft, to the tune of more than twenty-five degrees per second in both yaw and roll. The desired attitude of the LM was overshot, which in turn caused high reverse errors and rates. Both men cursed vehemently, Cernan’s going out over the air-to-ground loop.

Son of a bitch.

Stafford was a former test pilot who had been through the heart-stopping launch abort of Gemini 6, and he knew that the situation in which he and Cernan found themselves was dire. That he admitted it out loud seemed to be proof of just that.

We’re in trouble.

Helpless, Duke got on the loop.

Snoop, Houston. We show you close to gimbal lock.

“Any time you get close to gimbal lock, that’s really, I’d say, tense more than scary,” Duke remembered. “If you get into gimbal lock, you’ve lost your platform. You had to be very careful about that, so yeah, we were concerned and focused.”

Fifteen seconds after staging, during which time Cernan would say he saw the lunar horizon whiz by his window no less than eight times, the wildly gyrating rotations were at last nulled out. Official reports attributed the “attitude excursion” to human error, but the near disaster was an easy thing to overcome—do not make the same mistake again. It was not the result of some sort of flaw within the AGS or either of its three modes, so there was no need for an extensive redesign that might jeopardize the end-of-the-decade deadline. “It was something they knew quickly how to correct,” said Lunney, who was at the flight director’s console during the crisis. “The response was very quick and orderly. It got a lot of attention because of Gene’s purple response, but other than that, we were just trucking right along.”

There were other, less serious issues to deal with the rest of the flight. The Trench had pushed for a definite separation sequence when Charlie Brown and Snoopy parted ways for good in lunar orbit, but got overruled. “During meetings with Bill Tindall, we said, ‘When we get ready to undock, this is what we think you ought to do,’” said retro officer Chuck Deiterich. “Stafford said, ‘No, no. Don’t worry about it. I can handle it. I’ll just get away from it.’ Well, of course, you don’t argue with Tom Stafford.”

12. Despite the good-natured presence of Snoopy and Charlie Brown dolls at his console, capcom Charlie Duke and the rest of the MOCR were forced to listen in during Apollo 10’s deadly serious attitude excursion. Courtesy NASA.

When it came time for the two spacecraft to undock at 108 hours, 24 minutes, and 36 seconds into the flight, their separation attitude had the LM pointed toward the sun. A fitting had been incorrectly installed on the docking tunnel vent prior to the flight, and when Snoopy was jettisoned, residual air in the tunnel popped it directly into the glare of the sun and momentarily out of the crew’s view. “In itself, this would not be a big deal, but the ascent stage was about to send the LM into a solar orbit,” said Deiterich, who made sure to be in the MOCR when the moment went down. “It can be a bit unnerving when the exact location of a nearby thrusting vehicle is unknown.”

Once the LM was free and clear, its ascent batteries lasted for another twelve hours or so. Bob Carlton finally had his chance. “The questions were exceedingly important in my mind, and the hardest of all to get answers to,” he said. “We had the LM in orbit, so we played with it . . . we experimented with it . . . or . . . we tested it. We turned the coolant off to the platform, just to see how hot it could get and still work. We watched the batteries go down to zero, and we experimented to see which valves and equipment quit first.”

It was not just in flight where he got help, either. An LM was undergoing a thermal vacuum test at MSC when somebody forgot to turn on the coolant to its guidance, navigation, and control systems. Although they overheated, of course, they continued to work long after their predicted tolerances. “We got our hands on that data and, man, you talk about pleased, tickled, a gold mine—that was a gold mine,” Carlton added. The process continued during the next couple of lunar missions, to the point where Carlton felt comfortable with his LM data.

If Stafford and Cernan had found themselves in deep water during the wild gyrations in lunar orbit, EECOM Sy Liebergot also came face-to-face with trouble on the long coast back to Earth. A short caused the circuit breaker for Fuel Cell 1 to trip, and when attempts were made to reset it, it triggered master alarms and undervoltage and failure lights. As a result, the fuel cell was reconnected to its bus only when the skin temperature of the CSM cooled to 370 degrees and then disconnected again when it reached 420 to 425 degrees. It was operational, but just barely.

Liebergot was on duty when the problem took place 120 hours, 46 minutes, and 49 seconds into the flight and he briefed his Orange Team flight director, Pete Frank, on the issue. If it had taken place on the outbound trip to the moon, mission rules would have prevented an undocking. But now? There was no real impact. John Llewellyn, however, had evidently not heard Liebergot’s explanation. “We all had twenty-five-foot coiled cords on our headsets so we could move around beyond our console,” Liebergot began. “So he leaped out of the Trench, came up to my console, and yelled at me, demanding to know, ‘What the hell’s this thing about a fuel cell?’” Liebergot very carefully told Llewellyn that he had just explained the situation over the flight director’s loop. According to Liebergot, that set Llewellyn off: “He got right in my face and said, ‘Look, you son of a bitch. If you don’t tell me what I want to know right now, I’m going to kill your ass right here.’” Liebergot’s recollection begged the question—did he go over the fuel-cell problem again with Llewellyn?

Charlie Brown reentered the earth’s atmosphere traveling an astounding 36,314 feet per second—at approximately 24,760 mph, it was the fastest any human beings had ever traveled before or since. The Command Module splashed down just a mile and half from its target point, and just 3.3 miles from its recovery ship, the USS Princeton. Future GNC controller Terry Watson was working in the Landing and Recovery Division at the time, and when Milt Heflin offered to let him power down the spacecraft, he jumped at the chance. At the same time, however, he also wondered if there might be something else he could be doing. “Milt gave me all the manuals and stuff, and so I got to climb in the Command Module and pull all the waste management stuff out and all the suits and pack up all that stuff,” Watson remembered. “When I did all that, I thought, ‘Is that all there is to this job?’ When I got back to Houston, I just said, ‘I think it’s time to move on.’”

It was, in fact, time to move on for not only Watson but NASA as well. Looking back, it is hard to comprehend just how far the agency had come in such a relatively short amount of time. There had been plenty of highs, and plenty of lows:

President Kennedy’s speech before Congress, saying that he believed the nation should commit itself to the goal of landing a man on the moon before the end of the decade.

Being one-upped so many times by the Soviet Union.

Mercury’s baby steps.

The bridge built by the Gemini program.

The devastation and doubts cast by the Apollo 1 fire.

A gutsy gamble to send Apollo 8 to lunar orbit.

The dress rehearsals of Apollo 9 and 10.

All of it had led to this very point. It was go time.