7

A Bunch of Guys about to Turn Blue

After the first four Apollo crewed missions, there was nothing left to accomplish other than the grand prize itself.

As momentum built following each of the flights, those who worked in and around the MOCR were looking forward to the next before the Command Modules ever finished dripping on the recovery carriers after splashdown. “Everybody worked as if they knew this was a noble thing to do,” remarked Glynn Lunney, on tap to serve as flight director for Eagle’s lunar liftoff. “It was something where people came because they wanted to participate. When it came time to land, we’d been working on this for a long time—say a decade. The truth is that mankind had been waiting for this for thousands of years. Imagine all those people sitting around their fires, coming out of their caves. The moon had to be a big mystery to them—this great, big ball right up there.”

The Wright brothers had managed the first powered flight just thirty-three years before Lunney’s birth—Orville was still living when young Mr. Lunney made his debut into the world. Lunney knew of outhouses, iceboxes, and wicker lamps in his youth, and his family did not own a car until after World War II. Barely more than three decades after Kitty Hawk, Lunney helped to land human beings on the moon. The Apollo program in general and Apollo 11 in particular, Lunney concluded, represented the pivot point from the horse-drawn past to the supersonic future.

Who could argue the point? Certainly not Dave Reed, the twenty-eight-year-old FIDO who drove a green-and-black 1929 Model A Ford sedan with straw-colored wheels and whitewall tires to work.

To INCO Ed Fendell, the uproar kicked up by the flight was a moot point. A fifty-fifty shot at landing might have been the opinion of most of his coworkers, but it was not Fendell’s. There was no way, none whatsoever, that Apollo 11 was going to make it down to the surface. “Hell, no,” Fendell began. “How many things have to work right to make that happen? You start with this incredible rocket that has to stage and the next thing has to burn. Then, it has to stage the S-IVB burn. Then, you’ve got to get into the right orbit. Then, you’ve got to burn the S-IVB again to get you going out toward the moon.”

Fendell was not finished. The CSM Columbia would have to perform all but flawlessly, and so would the LM Eagle. The procedures would have to be spot on. Something somewhere, he was sure, would go wrong and prevent Armstrong and Aldrin from sticking the landing. “You’re telling me you think you’re going to make it the first time?” Fendell concluded. “Not if I’m in Vegas. Not with my money you ain’t. I ain’t turning you loose with my American Express card.”

Fendell was not even sure if Apollo 12 would be able to make a landing. Or Apollo 13. If NASA was lucky—really, really lucky—a landing might finally be accomplished on the fourth try. Maybe.

Steve Bales was on the hot seat, and he knew it.

Training for Apollo 11 began in earnest a month or so before the launch of Apollo 10, and as the very first powered descent simulation was about to begin, Bales heard someone plug into a spare port his console. It was probably just branch chief Jerry Bostick or section head Charley Parker, checking in to see how things were going. When he saw who the visitor actually was, Bales’s heart skipped a beat. It was the godfather himself, the one and only Chris Kraft.

Bales was already keyed up for the test. Protecting the ability to abort placed several critical scenarios squarely in the guidance officer’s lap. The theory was this. If the capability to abort on the primary guidance system was either lost or about to be, then the landing would be called off. This was a system that contained what in the twenty-first century would be considered a measly thirty-six thousand words of fixed read-only memory, plus another two thousand words of erasable random-access memory. Between the guidance computer in Eagle and an identical one in Columbia, the combined onboard computer memory of the two spacecraft that made humankind’s first lunar landing possible was dwarfed by that of just one ordinary smartphone decades later.

Miniscule computing power was just one of many issues that made protecting abortability an iffy proposition, and it was open to all kinds of debate. According to Bales, “The first question would have been, ‘You guys aborted this first chance to land on the moon, this multibillion-dollar program that was a symbol of America’s prestige? Why? Because the computer couldn’t have done an abort? Could it have landed safely?’ Well, possibly, yes.”

The descent to the lunar surface, Bales knew, presented few if any great choices. An abort was risky. Going on was risky. He had a lot on his mind while getting geared up for the flight’s initial trial run, and now, the whole back row was filled to the brim with management types. The VIP viewing room was nearly full as well, and Kraft was front and center in the Trench with Bales. He almost always simply listened in on a squawk box installed in his office or positioned himself with the rest of management in the room’s uppermost row, but not now.

Gulp.

“I almost said, ‘What the hell?’ but I didn’t,” Bales remembered with a laugh. The simulation began, and sure enough, his velocity numbers on the LM’s descent started rising. Then, they rose some more. Finally, they got to the point where he had no other option than to call off the landing. It turned out to be exactly the right decision to make. If he was going to be replaced by his section head, Charley Parker, a mistake in the first sim would have been cause to do it. There was a lot riding on Bales’s actions that day, and he nailed the abort call with Kraft sitting right there next to him.

Kraft slapped Bales on the shoulder, told him that it had been a job well done, and then returned to his perch in the back row. It is not hard to imagine the relief that must have coursed through Bales.

While the final couple of weeks of training did not turn out nearly as well initially, they went a long way toward making the actual landing possible. Simulation supervisor Richard H. “Dick” Koos, according to Kranz, “kept beating us up and beating us up and beating us up.” One day, Kraft called Kranz on a phone behind the flight director’s console. “There wasn’t any help this guy could give me,” Kranz said. “I mean, there was nothing. The only help he could give me was to maintain his confidence that I was going to get it all together.” Kranz responded to the call by turning the ringer off on the phone. “At times, it got so bad that the prime crew, Apollo 11 crew, Armstrong and Aldrin, just didn’t want to train with us anymore, and we didn’t want to train with them, to the point where they’d go off in a different simulator and we’d work with the backup crew or work with the Apollo 12 crew.”

The final sim was on 5 July 1969, and with the prime crew already in Florida preparing for launch, the training session was left up to Pete Conrad and Alan L. Bean of Apollo 12, and their backups, Dave Scott and James B. “Jim” Irwin. Late in the afternoon, with several successful runs already under their belt that day, Gene Kranz felt his team was primed and ready to go.

Dick Koos was about to throw the control team a wickedly breaking curveball with the count full, two out, and bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth inning of the World Series. A few minutes into the descent, a computer program alarm cropped up. Bales remembered it being a 1210 alarm, Kranz a 1201. Whatever it actually was, the alarm was about to wreak havoc in the control room.

“1210 meant two users were trying to access the computer at the same time,” Bales explained. “I’ve never thought that was a planned failure. I think something went wrong with the simulator. They never ’fessed up to it, nor would they. It didn’t matter if it was planned or not.” That might not actually have been the case, because Jack Garman had been working both sides of the fence by helping the sim teams come up with various computer failures to throw in during training. Just like that, Bales was struggling to figure out what to do with an issue very similar to what Garman had suggested.

On what had long been considered graduation day in the MOCR, Bales made up his mind.

Abort!

Kranz confirmed, and Scott and Irwin were off to the races in exactly the opposite direction they had planned to be going. If the abort was a frustrating decision to make, the post-sim debrief was even more so when Koos made it abundantly clear that the landing could—and should—have continued. “I felt that we had made the right, necessary call, but I was really unhappy with Koos,” Kranz wrote in his autobiography. “Dammit, we should have finished our training with a landing on the surface.”

“We were very young,” Garman added. “It wasn’t funny, particularly when Gene Kranz started bawling out the sim guys, saying they never should have given us a sim like that and the sim guys turned around and bawled out Kranz, because it was supposed to be a survivable kind of an issue.”

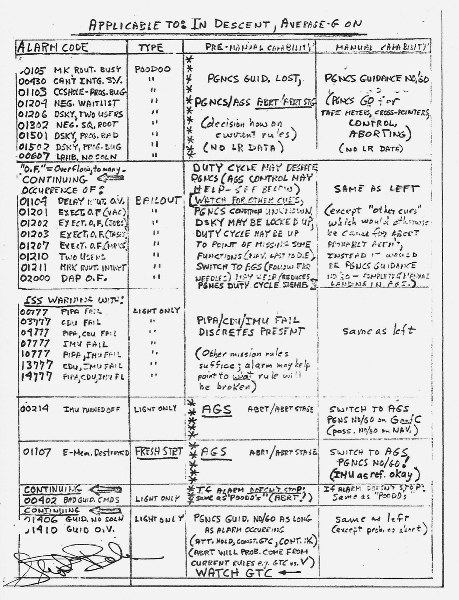

When the smoke cleared, Kranz asked Bales to come up with a list of computer alarms and to note which ones would require an abort and which would not. Bales did not want to do it, because he already had a mountain of work to plow through before the actual mission began. Instead, Bales went to Garman. Computer software was Garman’s specialty, and he knew and worked with MIT virtually every day. Bales took Garman’s findings and added a list of program alarms to his mission rules that would mean an abort.

1201 and 1202 were not among them.

Garman also developed a handwritten cheat sheet list, placed one under the glass at his console in the SSR, and gave one to Bales. “Thank the Lord he did,” Bales admitted. “I thought we’d never use the sheet. I thought that was just the biggest waste of time.” Bales stopped, then reconsidered what he had just said. “Not that it was a waste of time, but I thought it wasn’t the top priority thing we needed to be doing at the time.”

Bales and Garman would be forever thankful for that little slip of paper come landing day.

Over his comm loop, FIDO Dave Reed sounded ever so poised and confident as the launch of Apollo 11 approached on 16 July 1969. His callouts were crisp and precise, just the way he had always done them.

From the sound of it all, there was also no sign that he was deeply disappointed in not being assigned as the FIDO on the flight’s lunar descent team. The plum role went instead to Jay Greene. Although Reed was lead FIDO on the next three flights and got to do lunar landings on both Apollo 12 and 14, there would never again be a first landing. “After having formed my career around the Lunar Module and having flown Apollo 9,” he said, “I was at the very least confused why Jay would get that role given that he wasn’t at all that familiar with the LM. Made no sense.”

The call was made by the head of the FIDO section, Ed Pavelka, who would later insist that the decision had nothing whatsoever to do with choosing one operator over another. He felt it was just another shift that had to be staffed, and Reed had been buried in work as lead FIDO on Apollo 9. According to Pavelka, he had not considered the implications and said that when the manning list went out, Reed was furious. “He could not stand it,” said Pavelka, who died on 26 August 2005. “He was going to be on console for the first landing, and he went to my boss. We ended up sitting down, and I went through the rationale. He just was not going to have the time to spend in the preparation because of his other assignments that he was totally involved in.”

13. After taking a shellacking during simulations for the flight of Apollo 11, Jack Garman put together this cheat sheet to have on hand back in the SSR. As it turned out, the sheet came in very, very handy during the landing. Courtesy Jack Garman.

Reed was so upset, Pavelka felt that it led to his joining former flight director John Hodge and fifteen others who left NASA a couple of years later to move to a Department of Transportation project in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Reed told his bosses that Apollo 13 would be his last flight, but when that mission went the way it did, he could not leave on such a note. And while Apollo 14 was Reed’s swan song in the MOCR, he insisted that not getting a spot on the first lunar landing team had nothing at all to do with his departure. “No, the reason I left was that the job had become routine and the excitement had puttered out,” Reed said. “I recall sitting on the console for launch of 14 and my heart rate didn’t elevate until T-minus two minutes. That was not fair to the entire operation. My edge had dulled.”

That was one reason. NASA politics was another, in that it seemed to Reed that decisions were beginning to be made by committee. “Things changed,” he said. “You could see this bureaucracy creep in, and it wasn’t as much fun. The juices weren’t going to flow in that kind of environment. We figured going up here to this brand-new place, we could start all over again. That’s why we left.” Toss in a divorce, and Reed concluded that “Houston just wasn’t the place it had always been.” Born in Nebraska and raised in Montana, Reed was deep down an adventurist seeking one challenge after another. The former FIDO eventually got shot at in Mogudishu, Somalia, while on an assignment for the Department of Defense; worked with the Drug Enforcement Administration on drug busts; traveled to Saudi Arabia following the first Gulf War; introduced advanced satellite technologies in the enforcement of sanctions in Serbia for the United Nations; and flew around the world several times on board the air force’s heavily modified “Speckled Trout” KC-135.

Bob Carlton arrived early for his shift on the morning of 20 July 1969, as did virtually everyone else on the landing team. That was not necessarily anything out of the ordinary, though. Controllers always showed up before they took over on console to see if there were any issues they needed to know about. Carlton got off the elevator on the third floor, and almost as soon as he did, he got an ominous message that officials from Grumman—the maker of the LM—needed to speak with him. From the foreboding tone of the message and its urgency, he had a gut feeling the conversation was not going to be a pleasant one. What the builders of the LM had to say left Carlton dumbfounded.

A potential fracture mechanics problem had been detected in the propellant tanks—in essence, the metal of the high-pressure tanks was designed to expand and have some elasticity, much like a balloon. However, there was concern that the issue might cause the tank walls to get thinner and weaker as they stretched and possibly rupture in the process. The descent engine was nestled right beneath those tanks, and the hotter it got during the landing, the hotter the metal of those tanks could become. The risk was obvious.

Worse yet, there was no way to quantify the extent of the problem. There were temperature sensors on the tanks, but there were no numbers to determine when an abort should be called or even when the tanks should be watched, in Carlton’s words, “super close.” The only thing coming his way was that there might be some sort of issue, that it could be serious, and that the tank might blow up if it got too hot. How hot was too hot? No one could say for sure.

“Can you imagine my feelings?” he asked. “I didn’t know how to handle it. They hadn’t given me enough information to handle it, but I dang sure wasn’t going in there and tell the flight director we weren’t going to land this mission.” A couple of days past the forty-fourth anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing, the moment seemed as fresh and as vivid in Carlton’s mind as it was that day back in July 1969. He did not inform Kranz because, he continued, “it was a very complicated thing, and I didn’t have the answers. We would’ve had a long, big discussion taking place when we ought to have had 1,001 other things in high-priority mode. I just didn’t want to sidetrack us with something I did not have figured out. It was pointless to sit down and discuss it with Kranz. All I would have done is introduce a great big factor of confusion, alarm, concern. It would’ve focused our attention away from what we ought to have been looking at. There was a heck of a lot going on.”

Carlton trudged into the MOCR “almost paralyzed,” he admitted. His plan was this—he would keep an eye on the tank temperature gauges, and if they happened to spike, he would call the SPAN room and have Grumman’s representatives explain the need for an abort. In his mind, it was the only solution.

Situated on the far-right end of the second row, Carlton could peer over the top of his console at Steve Bales, who was situated at the guidance console in the Trench. Bales felt like he had the weight of the world on his shoulders as well. The computer alarms that triggered the aborted sim were still fresh on his mind as he walked into the MOCR. When he did, instead of a comfortable seventy-two degrees, the air in the room felt more like ninety with humidity every bit as high. The consoles might as well have been sitting outside in the hot Houston sun.

Carlton and Bales were not the only ones in the control room who were “clutched,” as Carlton would have put it. Kranz knew that, and he also knew that he wanted to say something to reassure his troops. He called for everyone in the MOCR to go to the assistant flight director’s private communications loop—no one else would ever hear what he was about to say, because it was not recorded—and then began:

Okay, all flight controllers, listen up. Today is our day, and the hopes and the dreams of the entire world are with us. This is our time and our place, and we will remember this day and what we will do here always. In the next hour we will do something that has never been done before. We will land an American on the moon. The risks are high. That is the nature of our work. We worked long hours and had some tough times but we have mastered our work. Now we are going to make this work pay off. You are a hell of a good team, one that I feel privileged to lead. Whatever happens, I will stand behind every call that you will make. Good luck and God bless us today.

For Bales, the pep talk was exactly the thing he needed to hear at exactly the moment he needed to hear it. Bales would have been willing to follow Kranz through hell itself that day, and he was not alone. “I still keep [Kranz’s words] with me today. That’s how important it was,” Bales said. “He was saying to us, ‘We’re going to do the best we can. If it doesn’t turn out well, we all go out of here saying it didn’t turn out well, not that it was that guy’s fault or this guy’s fault.’”

Telcom Jack Knight was not assigned to the landing phase, so he was in the SSR to follow along with the play-by-play. He heard Kranz’s speech, and wished for decades afterward that it had been recorded for posterity’s sake. It was so powerful that it brought Knight to a place of deep emotion even after all those years.

When Kranz finished with his remarks, he ordered the control room doors locked. It was time. The next few minutes would be some of the most tense and compelling in the lives of those who worked the flight in the MOCR and back rooms. The descent orbit initiation (DOI) began on the far side of the moon with a thirty-second burn that placed Eagle into an orbit that swung the LM to within fifty thousand feet of the lunar surface on the near side. As soon as the spacecraft peeked out from behind the moon, controllers around the room raced to get readings to ensure that it was safe to continue with a powered descent initiation (PDI) burn designed to bleed off the LM’s orbital velocity.

Nearly sixteen minutes after coming back around to the lunar near side, the PDI braking phase commenced. It began with a short twenty-six-second burst of the descent engine at just 10 percent thrust, known as an ullage burn, to force floating propellant into the engine’s intake valve. Data dropped out just then, and as Duke relayed a message through Collins in Columbia to have Aldrin switch antennas, PDI began in earnest by throttling up to 94 percent of the descent engine’s rated thrust. Starting out in a heads-down position so Armstrong and Aldrin could get a quick visual read of their altitude and range by checking out the lunar surface, Eagle then swung around to heads up, where the astronauts faced the nothingness of space as the LM’s landing radar locked onto the surface. As soon as it did, Bales knew something was amiss.

Eagle was descending too fast, to the tune of twenty feet per second. At thirty-five feet per second, Bales would have been forced to call an abort. He was already more than halfway there, and there were plenty of “what ifs” to consider. What if the guidance system was misaligned? What if one of the accelerometers had a bias? What if the error continued to grow?

A decision to call off the landing was staring Bales in the face, but in just thirty seconds or so, he was able to figure out that there was nothing wrong with the flight computer’s navigation capability. Instead, PDI had begun and was proceeding with the LM some three miles farther down range than expected. No one would ever know for sure what caused the problem, but there were, of course, theories. Some figured that residual air in the docking tunnel somehow popped Eagle into the error when it undocked with Columbia. Others felt that small inputs from the Reaction Control System (RCS) made the difference.

Whatever the cause of the issue might have been, Bales was satisfied and remembered turning to FIDO Jay Greene and remarking, “We’re in great shape.” He could not have known that his and Jack Garman’s biggest test was yet to come.

A few moments later, Kranz went around the horn with a round of “go/no go” calls to continue the descent. If Bales became well known in later years for anything other than serving as guidance officer for the Apollo 11 lunar landing, it was his—what’s the best way to put this?—enthusiastic “Go!” calls while doing so. Garman joked that Bales yelled because he had yelled, but each of Bales’s calls that day was pronounced, and Bales would later say that was the way he almost always did it. Granted, these were probably a little more adrenaline charged than others he had made during sims. “If Don Puddy would’ve started talking in the tone I talked, Gene would’ve thought something was wrong with Don,” Bales said. “But he knew each one of us, and we would just talk differently. I was cranked up, high volume, high everything. In fact, I suspect that if I’d have been quiet, he would’ve thought something was wrong with me.”

During the go/no go poll to press on with powered descent, Bales all but bellowed his affirmation, and after he did so, there was a brief but very definite chuckle in Kranz’s voice as he pressed on to other controllers. The flight director was not the only one who apparently enjoyed Bales’s calls that afternoon.

The conversation with Grumman was still haunting Carlton. He had also since dealt with an erroneous thruster failure signal on Eagle during the descent. He had seen a similar issue during a simulation leading up to the flight, and he knew that it was merely an instrumentation issue when the thruster’s gimbal numbers remained rock-solid steady.

“The sim guys saved my neck,” Carlton said. “I don’t know what I would’ve done if we hadn’t come up with that little scheme, because when you saw a failed-thruster light on, I was spring-loaded to the panic position.” When Kranz asked for the PDI go/no go, Carlton was “as taut as a wire” and actually gave his consent before Kranz even asked him for it.

We’re going, Flight.

The very next call was to Bales, and Carlton would always appreciate the fact that his fellow flight controller was so youthfully exuberant. “He said, ‘Goooooooooooooooo!’” Carlton remembered with an all-out laugh. “I empathized with that, because I thought, ‘You know, I’m just that strung out myself. I’m glad he did that, because now I’ll make a special effort to sound calm. It probably would’ve been me that did it, if Steve hadn’t done it. It relieved the tension, though, then everybody kind of relaxed a little bit.”

Bales could not relax just yet. Another computer alarm crisis was about to rear its ugly head.

From the moment the Primary Guidance Navigation and Control System computer was turned on, its resources began to be eaten away by an overload of some 10 to 15 percent. No one knew how hard the computer was working, and just five minutes into the powered descent, the first of five computer program alarms rang out.

Bales got on the loop to Garman.

1202. What’s that?

Garman responded.

It’s executive overflow. If it does not occur again, we’re fine.

The computer was working overtime and was in the process of dropping tasks that were not absolutely essential in order to concentrate on ones that were. Moments later, Armstrong was not so much requesting an answer as demanding one.

Give us a reading on the 1202 program alarm.

Garman quickly checked the cheat sheet he had put together, and told Bales that things were good to go for the time being. Just as the last syllable slipped from Armstrong’s lips, Bales assured Kranz.

We’re go on that, Flight.

The alarms sent Garman’s blood pressure “through the ceiling,” he would one day joke. “I just reacted,” Garman recalled. “I looked down, saw what it was, and told Gran Paules (who was sitting in on the guidance console during the landing) and Steve Bales that as long as it didn’t reoccur—and I meant to say, ‘As long as it didn’t reoccur too often’—that we were fine. If the computer was really in trouble, the vehicle would’ve started tumbling long before we had a chance to tell them there was a problem.”

The episode was a prime example of the working relationship between a controller in the front room and his back-room support staff. Bales’s copy of Garman’s cheat sheet was in a notebook, covered by various other sheets of paper. Even if it had been front and center, he might not have had the time to find the alarm in question. “I don’t know if Jack remembered it from memory or if he had this right out in front of him, but either way, he was faster than I was, which didn’t surprise me at all,” Bales admitted. Russ Larsen of MIT was seated next to Garman in the SSR, and he could offer only a thumbs-up during the computer alarms. Don Eyles, who would later save the day during the flight of Apollo 14, remembered that his MIT colleague once said that he had been too scared to actually form words.

As soon as Bales gave his go call, Duke was on the air-to-ground loop telling Armstrong and Aldrin that they could continue. He did not even wait for confirmation from Kranz. “I was winging it,” Duke said. “If you’re in the cockpit and you get this computer alarm, you start thinking about an abort. I thought it was critical that they get the straight word. When Bales said, ‘We’re go, Flight,’ I just said we’re go. I didn’t wait for Flight. Gene was going to say, ‘We’re go.’ That kept happening. He never said anything about it, so I just winged it at that point.”

Another 1202 alert was triggered less than a minute later and then three more alarms—one 1201 and two 1202s, signaling essentially the same issue—took place within the span of just forty seconds. After the third, Bales almost immediately called over the flight director’s loop with much more confidence in his voice.

Same type. We’re go, Flight.

A month after the flight, President Richard M. Nixon presented the crew with the Presidential Medal of Freedom at a grand ceremony in Los Angeles. The chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court was there, as were forty-four of the nation’s fifty governors and fifty members of the House of Representatives and Senate. It was an impressive gathering, and Bales was chosen to accept the NASA Group Achievement Award on behalf of its mission operations group. “Steve Bales,” the president began, “made a critical decision just before Eagle landed on the Sea of Tranquility that could have made the difference between success or failure. . . . This is the young man, when the computers seemed to be confused and when he could have said, ‘Stop,’ or when he could have said, ‘Wait,’ said, ‘Go.’”

Those few moments were as quiet as Jerry Bostick had ever heard the control room. Personally, he felt that Armstrong was the right man for the job. He was not one who would have taken unnecessary chances. To put it another way, Armstrong was not going to do anything stupid. He would either abort safely or land. It was that simple. Bostick had the very same sense of confidence in Bales, so much so that he bought the young man a bottle of Scotch after the flight in celebration. “I felt very proud of everybody, especially Steve,” Bostick said. “I think he made the right decision at the right time. He made it without any stammering or hesitation. He performed a job that I expected all the guys in the Trench to do.”

Hugh Blair-Smith, who helped develop the guidance computer while at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory, wrote that a “myth” developed when some believed that the computer “had somehow ‘failed’ in a way that required human intervention or ‘takeover.’ The truth is exactly the opposite: the PGNS software had been deliberately designed to recover from such unexpected disturbances and persevere with the high-priority tasks that flew the vehicle. All the humans had to do was to notice that flight was proceeding correctly, and forgive the disappearance of some displays.”

The final three alarms took place after Eagle had pitched up to a not-quite vertical position in a process known as high gate. Beginning at an altitude of approximately seven thousand feet and four and a half nautical miles from the landing site, Armstrong and Aldrin could finally peer through their small windows and visually monitor their approach to the lunar surface. The final approach started, and in less than two minutes, the spacecraft dropped to just a few hundred feet above the surface. From maybe two thousand feet on down, Kranz knew that responsibility for the landing was rapidly shifting from the MOCR to the two men doing the flying. It was, after all, their behinds that were on the line in what Kranz and fellow aviators had always called the “dead man’s curve.”

Dead man’s curve? Absolutely. Every inch lower was new, completely uncharted territory.

As the descent continued through low gate, the point at which Armstrong could take over manual control, Eagle was coming down in a football-field-sized crater littered with boulders. Armstrong did just that at about six hundred feet up, and began to steer the LM clear of the treacherous rocks below. Back in the MOCR, no one could have known what Armstrong and Aldrin were seeing through their triangular-shaped windows. Duke told Kranz in a tone of marked seriousness, “I think we better be quiet, Flight.”

Duke’s boss in the astronaut office had triggered the request. “Deke Slayton was sitting next to me and he said, ‘Shut up and let ’em land,’ and I said, ‘Yes, sir!’” Duke remembered with a chuckle. “He was right. We were giving them too much information, I thought.”

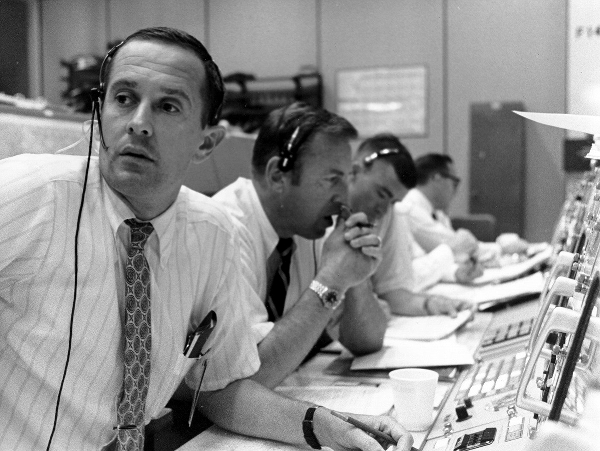

14. As Eagle drew ever closer to the lunar surface, capcom Charlie Duke asked flight director Gene Kranz for silence over the comm loops. Kranz quickly complied. Courtesy NASA.

Kranz answered the future moonwalker’s request by telling his controllers that from that point on, the only callouts would be for fuel. Carlton knew that those levels were already low, and getting lower. It had always been his nightmare to have an LM run out of fuel while landing and not know it until too late, and this time at least, he could see it coming. A low-level sensor in the tank was uncovered in the tank as it neared empty, with maybe a couple minutes’ worth remaining. Sims had taught him what kind of fuel levels to expect at various altitudes in the landing cycle, and Carlton’s heart dropped.

Fuel had never been this low this high up, and even when the craft came back over the crater’s lip and the altitude lessened suddenly, the remainder was still lower than he expected. Generally, Armstrong and Aldrin had already landed in simulations well before Carlton ever saw the low-level light flash on his console. Not this time. “Knowing that we were going to land long, I was prepared for us to go low of fuel, but I had no idea we’d run as low as we did,” Carlton said. “We saw low level, and I glanced at the altitude and I thought, ‘Ohhhh, crap.’ I didn’t know if we were going to make it or not.”

Kranz and Carlton both knew what was about to happen. Kranz called, using his colleague’s name instead of console position.

Okay, Bob, I’ll be standing by for your callouts shortly.

Carlton noted the low-level light, and then a few seconds later, told Kranz to stand by for word that only sixty seconds’ worth of fuel was left. Another call came, and nobody wanted to hear it.

Sixty.

Kranz repeated.

Sixty seconds.

Duke passed word up to the crew, just as the engine started to kick up dust. This was going to be far too close for comfort, but from the sounds of their voices, it might as well have been just another simulation.

Stand by for thirty.

Thirty.

Again, Kranz and Duke echoed the call. In the Trench, retro officer Chuck Deiterich was as cool as a cucumber. He was not sweating the landing. “I never really got too excited about it,” Deiterich said. “I felt they had enough time to get down, so I wasn’t concerned about an abort. Thirty seconds is a long time. Maybe I was being naïve, I don’t know. But when you work in the control center, you worry about your job, you worry about the other people you might affect, and you worry about how they might affect you. Something like how much propellant they’ve got is Bob Carlton’s call, so you trust him to do the right thing. It’s a team effort.”

Moments later, probes extending from three of the LM’s four legs made contact with the surface. Aldrin called it.

Contact light.

Eagle’s engine stopped, and as the astronauts raced through their procedures checklist, Carlton saw the stoppage on his console. He confirmed it to Kranz with little sign of emotion in his voice.

We’ve had shutdown.

By the count of the stopwatch Carlton was holding in his hand, only eighteen seconds of fuel remained before he would have been forced to call an abort. There was actually closer to forty-five seconds or so, but Carlton had intentionally left a reserve due to the amount of time an abort call would have taken to pass from him to Kranz to Duke to the crew and for action to have been taken.

It was at that point that Armstrong’s voice rang back to Earth. Houston . . . uh . . . Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed. Armstrong told Duke beforehand not to be surprised if the landing site was so named, but most in the room, including Kranz, had no inkling what it might be called.

Even if he was expecting “Tranquility Base,” the capcom momentarily fumbled his response in an excited rush of adrenaline. Roger, Twan . . . , Duke began, then paused a brief second before continuing, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You’ve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot. Minutes later, Duke would remind Kranz of the landing site’s call sign. Kranz replied, apparently ribbing him for his slip:

Okay, that sounds like a good one . . . if you can say it.

Bales was sure the “guys about to turn blue” crack had been aimed squarely at him. “I was one of them who was about to turn blue,” Bales laughed. “I looked over at Jay Greene. He was the opposite of me. He was always cool most of the time, and even he could hardly talk. We made it. We made it. We made it.”

Kranz did not have time to react one way or the other, because his attention was immediately focused on the first polling of his control team on whether Eagle could remain on the surface—and it could not continue to be called go/no go. Bill Tindall was considered the architect of the techniques that took Apollo to the lunar surface. He had once wondered in one of his famous “Tindall-gram” memos, “Once we get to the Moon does Go mean ‘stay’ on the surface, and does No Go mean abort from the surface? I think the Go/No Go decision should be changed to Stay/No Stay or something like that. Just call me ‘Aunt Emma.’” Tindall was such a respected member of the NASA community that Kranz invited him to sit next to him at his console during the landing as an honorary flight director, leader of Gray Flight. “Tindall was the guy who put all the pieces together, and all we did was execute them,” Kranz said. “I saw him up in the viewing room, and I told him to come on down and sit in the console with me for the landing. He didn’t want to come down, but basically I cleared everybody away and we had Bill Tindall there for landing. I think that was probably the happiest day of his life, a spectacular guy.”

As a result of Tindall’s memo, it did in fact become a stay/no stay call. Kranz was so intent on the job at hand that he had already told the MOCR to stand by for the T1 decision before Armstrong uttered his famous “Tranquility Base” line.

Almost from the moment it was confirmed that Eagle had settled into its nest in the Sea of Tranquility, background clapping could be heard over the comm loops. The viewing room erupted in cheering, clapping, stomping on the floor, and banging on the glass. Kranz would have none of it. “My immediate job was to keep my team focused on the task,” Kranz said. “It was pretty tough to do. That was the one surprise. For all the training we’d done, we’d never had people in the viewing room who erupted in cheering and stomping their feet. The sound of their recognition of the landing sort of filtered into the control room, so it really was a question of keeping everybody focused because we’d really been sucking air in those last two minutes.”

Finally, Kranz had enough and barked, “Okay, keep the chatter down in this room.” As he brought everyone else’s emotions under control, Kranz was trying to do the very same thing for himself. He was getting choked up with emotion. “It’s sort of like your first landing in a high-performance jet aircraft was,” Kranz said. “As soon as you touch down, you have that instant of exhilaration to say, ‘I did it!’ You have to stay focused upon the task, because you still have the landing rollout. You’ve got to lower the nose gear. You’ve got to make sure you don’t hit the barrier. To me, it was just a period of absolute, instantaneous recognition that we’d just touched down and then turning around very quickly to get back on track.”

At the exact moment Armstrong was telling the world that the Eagle had landed, Carlton was in the process of stopping any celebrations on the part of his SSR back room before they ever started.

Okay, fellas. Steady now. Stay with it. Keep your eye on it.

Bob Nance, who watched over the descent engine in the SSR, sounded almost incredulous moments after landing.

Looks beautiful.

Okay . . . keep your eye on it.

Nance’s voice was still filled with a tone of wonder.

Everything is steady, steady as a rock.

Carlton’s and Nance’s eyes were still glued to their consoles fifteen or twenty minutes later, as they stood ever vigilant over their bird. Nance noticed pressure rising in a line that led from a heat exchanger to the descent engine shutoff valve, and after he and Carlton scratched their heads for several minutes as to the cause, the loop lit up.

“Bob, I’ll tell you what it is!” Carlton remembered Nance announcing proudly. “It’s the heat exchanger. It’s froze up! It’s got the fuel trapped!”

Without acknowledging Nance or even questioning him about the issue, Carlton went onto the flight’s director’s loop and informed Kranz what was taking place. “You work together so long, one will start a sentence to talk about a problem, and the other will finish the sentence for him with the answer,” Carlton said. Carlton trusted Nance’s opinion to the point where he did not question it in the least. He was that confident going to Kranz with the information.

During post-landing venting of the fuel and oxidizer tanks, a small amount of leftover fuel froze in the heat exchanger and that in turn caused the rising pressure in the line. “It was like a pressure cooker,” Carlton continued. If the propellant line had ruptured, would it have been that big a deal? The line was located in the guts of the descent engine, and the descent engine had already done its job. That much was true, but if the line burst and sprayed fuel onto the warm engine bell, what then?

Thirty-five minutes after landing, Armstrong and Aldrin were informed of the line’s increasing pressure. Both men later downplayed the risk, and it is not hard to imagine why. They had something else on their minds at that point—a moonwalk.

According to the Apollo 11 press kit, the long-awaited moonwalk was supposed to start nearly ten hours after touching down on the surface. That allowed for an extensive check of the LM, which was all well and good, but such a delay was also to have included a two-hour nap.

After the adrenaline-charged landing, few could have reasonably expected Armstrong and Aldrin to actually get any rest during the rest period. They had not come all that way just to get there and then go to sleep. With that in mind, Bruce McCandless figured he still had some time on his hands and headed home for a bite of dinner before taking over as capcom for the EVA.

McCandless came from a long line of ultra-successful navy men—his maternal grandfather and his father were both awarded the Medal of Honor, and his paternal grandfather had risen to the rank of commodore. All four graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and the youngest McCandless graduated second in a 1958 class of 899 midshipmen. NASA came calling eight years later, and he became a member of the 1966 class of astronauts. By the time Apollo 11 rolled around, he was still waiting in line to fly.

A little less than two hours into the surface stay, Armstrong began to put an end to the will-they-rest-or-will-they-walk drama. “Our recommendation at this point is planning an EVA, with your concurrence, starting at about 8 o’clock this evening, Houston time,” the Apollo 11 commander told Duke, still on duty as capcom. It took Duke just twenty-six seconds to relay the ground’s agreement. McCandless’s home-cooked meal that night was not going to happen.

“By the time I got home, my wife came running down the driveway, saying, ‘They can’t sleep. Go back!’ I turned around and drove right back,” McCandless remembered. While returning to MSC, he looked up and spotted the moon. It did not look any different from the countless times he had seen it before, but this time at least, there was a huge change. He had friends and neighbors up there, and he was about to be talking to them in front of a worldwide audience.

McCandless made it back to the MOCR in time to join flight director Cliff Charlesworth’s Green Team for the start of the EVA preparations. Jim Joki and Bill Peters had not taken any chances on leaving the MOCR. They were in the control room for the landing, and when the big moment arrived, Peters remembered slapping Joki on the back so hard that Joki actually cringed. “He gave me such a slap, he knocked me right out of my chair,” Joki corrected with a smile. Joki was assigned to monitor Armstrong’s spacesuit during the moonwalk, while Peters was to watch over Aldrin’s. The fact they were there was proof enough that they suspected the EVA might very well be moved up.

“Jim Joki said, ‘They’re going to do it now. They’re not going to go to sleep. There’s no way,’” Peters said. “We manned up specifically to sit there and wait for it. We said, ‘We’re not going to sit at home and pretend to sleep while they get ready to do an EVA. No way.’”

The two EMU spots were separate positions in the control room through the first lunar landing, but from the flight of Apollo 12 on, responsibility for the spacesuits was assumed by the LM’s telcom console up in the second row. The slot was forevermore called telmu—or, if you happened to be Gene Kranz or Ed Fendell, “tel-uh-mu.”

For Apollo 11, Joki and Peters were situated at what had been the booster console on the left end of the Trench, nearest the door. Pete Conrad and Alan Bean were there, just months away from their own landing on Apollo 12. So were their backups, Dave Scott and Jim Irwin, who would eventually make the trip during the flight of Apollo 15. Before the two EMU guys could go to work, they had to shoo the astronauts away from their stations. “When it came time for us to work, I said, ‘Sorry, guys. This is my console,’” Peters said.

As Armstrong and Aldrin suited up for their stroll on the moon, Peters noticed that Aldrin was turning his suit fan on and off, on and off, on and off, cycling it five or six times for no apparent reason. Peters again jabbed Joki, this time more gently, to see if he might have a guess as to what was happening. “Jim was starting to be concerned he might burn the circuit out,” Peters said. “Of course, he didn’t. I asked Buzz about it at the fortieth reunion in 2009, and he wouldn’t admit to a thing.”

The suits were in good shape. It was time to go outside.

The conversations between McCandless, Armstrong, and Aldrin over the course of the two-hour EVA would be etched in the memories of the hundreds of millions of people around the world who were listening in.

Okay, Neil. We can see you coming down the ladder now.

I’m at the foot of the ladder. The LM footpads are only depressed in the surface out one or two inches, although the surface appears to be very, very fine grained as you get close to it. It’s almost like a powder.

Then, this. Pulses everywhere quickened.

Okay. I’m going to step off the LM now.

Compared to the expeditions undertaken by later landing crews that ventured miles from the LM, Armstrong’s first tentative move onto the surface was a mere baby step. That did not matter now. This was drama of the highest order.

That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.

Did Armstrong actually say, “That’s one small step for a man?” No, he did not, although he would later tell author Andrew Chaikin that he had intended to do so, and more than one apologist would later attempt to prove that the indefinite article was somehow lost in transmission. It was not, because he did not say it. McCandless could not say one way or the other. “I really cannot answer that question,” McCandless responded. “Prior to launch, I had asked Neil several times what his first words would be. He was always noncommittal. I think that he did not want to tempt fate. At any rate, when the time came, the communications link was just noisy enough that I could not tell whether there was an ‘a’ in there or not.”

McCandless said little in those first few minutes but finally broke onto the loop to remind Armstrong about scooping up a contingency sample of lunar rocks and dust. It would have been unthinkable had an emergency forced Armstrong back into the LM without at least a few examples for the rock hounds back on Earth to study, but humanity’s first moonwalker initially concentrated on describing the surface and a panoramic series of photographs of the landing site. McCandless attempted to bring Armstrong back around to the chore.

Neil, we’re reading you loud and clear. We see you getting some pictures and the contingency sample.

Just a few seconds later, after a prompt from Charlesworth, McCandless tried again.

Neil, this is Houston. Did you copy about the contingency sample?

Armstrong responded by telling McCandless that he would get to the sample as soon as he finished the panorama, and he did just that. That was exactly what it meant to be the only person in the world talking to men walking on the surface of another. “The job of the capcom is to help the flight crew and keep quiet, unless you have to say something,” McCandless said. “It was their show. My job was to communicate, keep them on a timeline, and make sure they didn’t forget something. It was a team effort.”

Keeping Armstrong and Aldrin on task was one thing, but keeping the president of the United States at bay was something else altogether. McCandless had no idea that President Richard M. Nixon might be placing a call to the moon. “Probably the biggest surprise was shortly after the EVA started, the White House came in and said that the president would like to talk to the Apollo 11 crew,” he remembered. “It was probably an oversight, but we had never considered that as a possibility. So for about an hour, my job was stiff-arming the president.”

The timeline was the timeline, and the leader of the free world would have to wait for his turn. At last, a little more than an hour into the EVA, McCandless called Armstrong and Aldrin to attention. Both were framed perfectly by the surface television camera, with Eagle and the American flag in the shot for good measure. McCandless called up to the crew.

Neil and Buzz, the president of the United States is in his office now and would like to say a few words to you. Over.

That would be an honor.

After a quick go-ahead from McCandless, Nixon’s unmistakable gravelly voice rang out over the loop.

Hello, Neil and Buzz. I’m talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House, and this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made from the White House. I just can’t tell you how proud we all are of what you . . .

Audio of the call dropped out for a split second, but when it returned, Nixon was in full song:

For every American, this has to be the proudest day of our lives. And for people all over the world, I am sure that they, too, join with Americans in recognizing what an immense feat this is. Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world. And as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to Earth. For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one; one in their pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.

The irony was simply too much to ignore in the coming years—Nixon made such a fawning phone call to Armstrong and Aldrin, only to kill the Apollo program not long afterward. McCandless did not have much more luck in holding off his boss, Deke Slayton, than he had with Nixon. McCandless had considered it an honor when Slayton, one of NASA’s famed Mercury Seven original astronauts and the all-powerful director of Flight Crew Operations, sat down just to his left in the MOCR. “I’d only been in the program three years, so he was like God, almost,” McCandless quipped.

If McCandless thought Slayton was going to give him a nice, casual pat on the back for a job well done during the moonwalk, he had another thing coming. With maybe an hour or so left in the EVA, half its planned length, Slayton insisted that McCandless have Armstrong and Aldrin start wrapping things up. “He started whispering in my ear, ‘Better start bringing them in now. You don’t want to take any risks. Let’s wrap it up,’” McCandless said. “Of course, that was not in accordance with the plan and everything else we had so carefully trained on.”

McCandless was in a bind. This was not a conversation that he wanted to have with Charlesworth over the flight director’s loop, and he could not get up, leave the capcom console, and go speak with him directly. There was simply too much going on for that to happen. “I didn’t want to get on the flight director’s loop and say, ‘Hey, Deke is harassing me!’ or whatever,” McCandless continued. “To make a long story short, I had two earpieces. I put the other earpiece in and pressed on. Deke never brought the subject up again.”

Or did he?

McCandless was a member of the 1966 astronaut candidate class, and fourteen of its nineteen members flew during Apollo, Skylab, and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. Three—Duke, Irwin, and Edgar D. Mitchell—walked on the moon. McCandless waited eighteen long years before he flew for the first time, as a member of the crew of STS-41B on board the Space Shuttle Challenger in early 1984. During the flight he was the subject of one of the most famous photograph of the Space Shuttle era when he became the first person to test the untethered Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU). The shot, taken by crewmate Robert L. “Hoot” Gibson, is a study in beautiful contrasts between the vast blackness of space, the pure white of McCandless’s MMU, and the blue beauty of the earth below.

Still, McCandless had been in line to fly a very, very long time, and he could not help but wonder why. Had Slayton and/or Chris Kraft been somehow involved in keeping him on the bench? “Thirty years after the fact, somebody said that they’d heard Kraft remark the reason I didn’t get a flight in Apollo was because of insubordination,” McCandless admitted. “The only incident I can relate back to was that one where I basically ignored Deke. I was also sort of naïve at the time. I have no idea exactly what happened.”

Eyes all around the room were all but glued to the large monitor to the right front of the room, watching as the two astronauts went about their work on the surface. Not Jim Joki, who would claim to be the only controller in the MOCR who did not peek at the television transmission even once. Not even Bill Peters, Joki said, could claim that distinction. “I never looked up,” he continued. “They should have had a heart monitor on me. When they got back in and got out of their gear and threw the backpacks on the lunar surface, I had a heart attack. No . . . not really . . . but there went all my equipment.”

The first part of President Kennedy’s directive had been accomplished with the landing and moonwalk, but the job was not finished. The second part—the most important part—was to return the crew of Apollo 11 safely to Earth.

First, though, somebody needed to figure out exactly where Eagle had landed. Dave Reed took over from Ed Pavelka at the FIDO console for the pre-lunar launch shift and set about trying to calculate an ignition time for Eagle’s ascent engine. The numbers would have to be precise in order to allow Armstrong, Aldrin, and Eagle to rendezvous with Collins and Columbia. The only problem was that with the down track error, combined with the maneuvering around that Armstrong had done to avoid the boulder field, no one was quite sure where Eagle had come to a rest. When he got settled in, Reed punched the comm button for the Real Time Computer Complex and asked for the landing coordinates. Reed was surprised by the answer.

Take your pick, FIDO.

Reed was in no mood for joking. No less than five different sites were possibilities—one from the Manned Spaceflight Network (MSFN) landing radar; one from the LM’s primary guidance computer; and another from the backup guidance computer; the targeted landing spot; and last but not least, the geologists had added their two cents worth based on the moonwalkers’ descriptions of the area. None of them were in close proximity to each other, and when combined with uncertainties over Columbia’s trajectory overhead, Reed said, “there were combinations of different answers, and multiple combinations thereof. The bottom line was that this was a relative problem.” Later studies showed that the LM was nearly five miles from the closest guess.

Pete Williams, who worked down in the first-floor Real Time Computer Complex, came up with a solution. Eagle could track Columbia with the rendezvous radar located at the very top of the ascent stage, and combined with an accurate read on the CSM’s orbital track, the process could work backward to the find the LM. Making matters all the more urgent, time was running out—Columbia had only two more passes overhead before the scheduled launch from the surface.

Reed unplugged from his spot in the Trench and made his way up to Milt Windler’s perch at the flight director’s console to explain the situation as best he knew it. “They instructed the capcom to wake up Buzz and tell him we wanted to do a rendezvous radar check,” Reed said. “We figured he’d pick up the Command Module coming over the hill. I’m sitting down there watching my screens and looking for the telemetry that is going to tell me that he got it. Sure enough, over come the vectors, Pete picks them up downstairs, and we recompute where the relative position of the LM is. By using the rendezvous radar, all the relative inaccuracies were nullified. That was the beauty of what we did.”

In coming years, Reed came into contact with Armstrong and asked if anyone had ever told the most famous astronaut of them all that the MOCR had not known where Eagle landed. “He was so cool,” Reed said. “He said, ‘No, you didn’t, but I figured that’d be your problem to solve, anyhow.’ That’s all he said.”

One last shift change put Lunney’s Black Team on duty for the departure from the lunar surface. Lunney did not seem all that concerned. “I think the landing and all that was associated with it and then watching the EVA were the high points,” he began. “When we got to the ascent back into lunar orbit, I think we felt that in some sense, the hard part was over. We knew that this had to work, but we were pretty confident it would.”

Hal Loden was not quite as certain down at the control console, and in the MOCR, responsibility for the ascent engine was his. It had been tested several times both on the ground and in flight, and there were all kinds of redundancies built into the control system for igniting it. Loden was comfortable enough with that part of the equation, but what about the unknowns? What might the Attitude Control System (ACS) do? What if more RCS propellant was used than had been planned? No one had ever lifted off from the lunar surface before.

The ascent had Loden’s attention. “That particular phase of the mission had never really been tested from the standpoint of real hardware, other than firing the engine and thrusters on test stands. So, yeah, I was a bit concerned as to what was going to happen.” Despite his butterflies, Loden was seeing nothing concrete that might have caused him to alert Lunney. All he could do was keep whatever apprehension he had at bay and hope for the best. “When you get down to zero, you can’t stand up and say, ‘Flight, I don’t feel good! Don’t do this!’” Loden continued. “You’ve just got to understand that the best minds in the engineering world have put that machine together, and we had the best pilots flying it. You’ve just got to go on faith that everything’s going to work right.”

Capcom Ronald E. “Ron” Evans helped Armstrong and Aldrin through their final preparations, and finally, Aldrin could be heard counting down their final seconds on the moon.

Nine.

Eight.

Seven.

Six.

Five.

Abort stage, engine arm, ascent, proceed.

Eagle had spent 21 hours, 36 minutes, and 20.9 seconds at Tranquility Base.

Millions of people were already beginning to come to grips with the enormity of what NASA had just accomplished. There were house parties, celebrations on town squares all over the world, and quiet vigils in bunkers in war-torn Vietnam. Ironically, it was the people closest to the situation who could not reflect on the flight of Apollo 11.

Reflection had to wait until after the flight or maybe even decades. Then and only then could anyone in the MOCR comprehend what had taken place that magical week in July 1969.

Surprised as he might have been about the successful landing, Ed Fendell had gone off shift shortly thereafter. He went back to his Houston apartment, and when he got up on the morning following the EVA, he went to a local dive for a quick breakfast. He sat down at the counter, unfolded a newspaper—which he still has—and started reading.

Two men soon sat down right next to him. They were a little older, grimy from work at a gas station just down the street. One of them started talking. “You know, I went all through World War II. I landed at Normandy on D-Day,” the man said. The man had his way to Paris, and on into Berlin. If he did not have Fendell’s full attention yet, he was about to when he continued, “Yesterday was the day that I felt the proudest to be an American.”

15. FIDO Dave Reed (light-colored jacket) gets his launch plot board signed during celebrations that followed Apollo 11’s splashdown. It eventually featured 139 signatures, including the crew itself after returning from quarantine. Courtesy NASA.

It was at that point that Fendell “lost it.” He paid as quickly as he could, grabbed his paper, and walked out to his car.

Once there, he started to cry.

Columbia splashed down at 11:50 a.m. Houston time on 24 July, almost dead center in the Pacific Ocean. The recovery carrier USS Hornet was thirteen nautical miles away, and as soon as Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins were safe and sound on the carrier deck, the MOCR erupted in unabashed celebration. In the midst of it all, Dave Reed was on the hunt for autographs.

Reed secured a three-foot by three-foot plot board that had been used in the Flight Dynamics SSR during launch and planned on getting it signed as soon as the mission was over. While most everyone else was checking out the screen at the front of the room to see if they might possibly be on television, Reed focused intently on scanning the crowd to see who might be available to sign the board. Collecting souvenirs from spaceflights was as old as the business itself, and if an item had actually been used during a mission, it was all the better. When he was finished, it had been signed by flight directors, controllers, astronauts, and various others who had some sort of connection with the flight of Apollo 11—139 people in all. The crew signed after getting out of quarantine. As his fellow controllers signed their names, Reed listed them all on a piece of scratch paper and then did some figuring.

The average age of the people who had just landed men on the moon was just twenty-eight years and change.

The priceless piece of history hung for several years in the lobby of Building 30. Then somebody decided that it should go to the Smithsonian Institution. Reed has not seen his signed plot board since.

That was not the only treasured memento that got away. An older gentleman broke out of the crowd during Apollo 11’s 16 August 1969 welcome-home parade in Houston to hand Neil Armstrong a small American flag. That was no small feat, considering the fact that some 300,000 people were estimated to have attended the celebration. The man was Harry Franklin Deiterich—Chuck’s father.

Later, Armstrong offered to return the souvenir to the younger Deiterich. Hindsight being perfect, the item would have held no small amount of significance because of both the original giver and the recipient. Rather than accepting it, however, the MOCR stalwart told the famous astronaut to keep the flag.