WITH KORSHAK, FACTOR, AND Dalitz shoring up the Supermob's interests in Las Vegas, Ziffren, Wasserman, and Reagan saw to it that California government would be well under control when the Vegas contingent eventually settled there. This meant attaining a vise grip over the state's political heart, and given the previously noted anarchy in California's party system, the takeover by the Chicago trust was accomplished practically overnight. All this would occur while Ziffren-Greenberg, Pritzker, Weingart, and Kirkeby-Hilton gobbled up hotels and commercial property, with Al Hart's City National Bank usually handling the monetary details.

Although ideology and money meant more than party alignment in California, Paul Ziffren was working to change that climate in favor of the Democrats. With the wealth and political connections that naturally accrued to major California real estate investors like Ziffren, he and his associates were able, ironically, to use the state's anemic party system to create strong parties—albeit with them in control. As the Supermob's hold on the state strengthened, it was not uncommon to find them in league with pols of both parties, many of whom would switch to the other party.

Like Ziffren, other transplanted Midwesterners were throwing their weight around in California's political inner sanctums. Among them were Jules Stein and Lew Wasserman, who had long since relocated their Chicago MCA headquarters to Los Angeles—Stein had planned the move for decades, having sent his trusted VP Bernard Taft Schreiber westward in the twenties to open the market. Much as Korshak and Ziffren had aligned with the career of Pat Brown, Stein and Wasserman were about to increase the Supermob's virtual invincibility with their nurturing of another California political wannabe, Ronald Wilson Reagan.

The Creation of Ronald Reagan

"Ronnie" Reagan, as he was then known, had moved to California in the late thirties, after a stint as a sportscaster for WOC Radio in Iowa, bent on transforming his career from radio announcer to movie star. After Reagan's marriage to actress Jane Wyman, Stein and Wasserman guided his career at Warner Bros., where he made a string of B pictures. With titles such as Swing Your Lady, Cowboy from Brooklyn, Girls on Probation, and Brother Rat and a Baby, Reagan, who was once credited as Elvis Reagan, rightfully attained the moniker The Errol Flynn of the B's. MCA was always more adept at deal-making and solidifying power than it was at creating great art.

When World War II broke out, Wasserman and Jack Warner persuaded the War Department to delay Reagan's draft induction in order to let him star in what would arguably be his best movie, Kings Row.1 After the war, Lieutenant Reagan picked up where he'd left off in Hollywood, joined Hillcrest Country Club, divorced Jane Wyman, and was forced to reassess his acting vocation, which was descending faster than a two-thousand-pound bunker buster.

In October of 1946, Reagan visualized his next career move when he spoke in Chicago at an American Federation of Labor (AFL) convention. Rousing the union members with anticommunist bombast, Reagan would learn, like other would-be pols such as Richard Nixon, that he could use red-baiting to craft a career in politics. Robert K. Dornan, nephew of comedian Jack Haley, recalled seeing Reagan venting at "Colonel" Jack Warner's house. "Ronald Reagan would be in a room talking a lot, even at parties, about how to keep the Communists out of Hollywood."2 His obsession with Communism led him to barnstorm in an effort to destroy the liberal Conference of Studio Unions (CSU), a federation of Hollywood craft unions; that quest sided him with the corrupt IATSE and MCA in order to combat fictitious "commies" in Hollywood. This clash in the labor-intensive movie industry is widely perceived as one of the pivotal labor struggles of the postwar era. Reagan's demonization of the CSU was not new; labeling the leftist unionizers "parlor pinks," George Browne had employed the tactic a decade earlier when he fronted for the Outfit's takeover of IATSE.3 Of course, the lefties were not aligned against the United States, but were merely a reaction to World War II fascism, and Reagan and cohorts surely knew it. Nonetheless, once the opportunistic Reagan picked up the anticommunist theme, he never let it go—it would be his ticket to success.

Reagan's stance was not without its drawbacks, however, as verbal jousts often threatened to turn physical. One former CSU operative, George Kuvakis, remembered how Reagan "had a limousine pick him up at his house, take him to work, and they were all armed . . . and they brought him home at night undercover."4

But Reagan's jingoism was even more ugly than people knew: in an attempt to curry favor with the FBI, Reagan undertook an insidious and secret anticommunist mission. According to a massive FBI file released in 1998, Reagan began meeting with FBI agents at his home in 1946, whereupon he gave the Bureau the names of actors Howard da Silva (The Lost Weekend), Larry Parks (The Jolson Story), and Alexander Knox (Wilson) as supposed Communists. Those and other names (deleted from the FBI documents) given by Reagan to the Bureau were eventually blacklisted in Hollywood. For the icing on the cake, Reagan publicly claimed that Hollywood liberals caused his lackluster film career to stall out as punishment for his hysterical anticommunist crusade.5

Ironically, Reagan's hand-wringing may have been a classic example of the maxim "He doth protest too much." According to the recent file release, the Los Angeles FBI Field Office reported that Reagan may have had his own "commie" connections: in 1946, Reagan was a sponsor and director of the Committee for a Democratic Far East Policy, which had been designated as subversive by the attorney general; he was also a member of the American Veterans Committee, cited as "communist dominated." Those were just the sorts of associations Reagan reported to Hoover that resulted in ruined careers for his fellow actors. Fellow actor Karen Morley, who knew Reagan at the time, opined, "It isn't that he's a really bad guy. What's so terrible about Ronnie is his ambition to go where the power is. I don't think anything he does is original, he doesn't think it up. I never saw him have an idea in his life. I really don't think he realizes how dangerous the things he really does are."6

Reagan's drive to free the acting community from the clutches of the Red Menace (coupled with a nudge from Lew Wasserman) motivated him to run for the presidency of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG), where he could become the endangered actors' father-protector. Years later, he verified the rationale in his autobiography, writing, "More than anything else, it was the Communists' attempted takeover of Hollywood and its worldwide weekly audience of five hundred million people that led me to accept a nomination as president of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG)."7

Although Reagan attained the post, not all in the acting community were convinced by his zealous rhetoric. Actor Alexander Knox commented, "Reagan spoke very fast . . . so that he could talk out of both sides of his mouth at once."8 Another SAG member said, "Reagan was a conservative, management-sweetheart union president and ran SAG like a country club instead of a militant labor union."9 And in a style that would presage his presidency, Reagan often seemed confused when tough questions were posed. But he was actually dumb like a fox, for as Hollywood labor expert and Fulbright Scholar Gerald Home wrote, "[He] almost seemed to use this confusion as a tactic: he had converted bafflement into an art form . . . he misstated dates and events at meetings. At one point he said jokingly, 'Pat [Somerset, another SAG official] says I am mixed up.' "10 Reagan would use the "kindly idiot" strategy not only in the presidency, but in future federal testimony when he was repeatedly quizzed about his furtive dealings with Wasserman. (It would also come in handy during the arms-for-hostages and Iran-contra gun-smuggling scandals of the eighties.)

Ronald Reagan's career in politics might have ended before it began were celebrities not virtually immune from prosecution in their Hollywood sanctuary. In February 1952, the actor with whom Sid Korshak occasionally went on the prowl set his sights on MCA starlet and single mother Selene Walters. According to Walters, a twenty-one-year-old combination of Kim Novak and Carole Lombard, it all started when Reagan introduced himself to her in the wee hours at Slapsy Maxie's nightclub. Walters recently recalled:

I was very impressed because he was such a big star. He asked for my address and phone number and I gave it to him. After my date took me home to my apartment, I got undressed, put on a housecoat. Then there was a bang on my door—it was about three A.M. I was afraid to open it at that hour.

"Who is it?" I asked.

"It's Ron—I just met you an hour ago. Let me in."

So I let him in. "I want to talk about my career," I told him. But he didn't want to talk about my career at all. So there was a lot of shuffling around on the sofa. I was struggling and kept saying, "Stop!" but he wouldn't. He forced himself on me and did what he wanted to do—in like a half a second, staining my nice housecoat in the process.

He said, "Listen, kid, I'll be in touch. We'll talk about your career later."

He never called me because he married Nancy Davis two weeks later. I didn't want any scandal so I never reported it. Besides, you couldn't sue a big star in those days. You still can't.11

Indeed, on March 4, 1952, Reagan married divorcee and actress Nancy Luckett Davis, and although his career was in the dumps, he refused to allow his new bride to live in anything but grand style. Living well beyond his means, Reagan purchased not only a home in Pacific Palisades, but also a 290-acre Malibu parcel for the amazing price of $65,000. Reagan was now under great pressure to afford his lifestyle, as well as pay a large tax bill that accompanied the land purchases. That pressure was soon to be relieved in the aftermath of one of Hollywood's greatest controversies, an episode that smacked of a Wasserman-Reagan-Korshak power play.

At the time, MCA and all other talent agencies were forbidden by SAG from becoming producers, for obvious conflict-of-interest reasons—a talent agent is at natural odds with a producer over the fees obtained by the talent. * With the recent arrival of the medium of television, which was centered in New York, all Hollywood-based businesses, including MCA, were feeling the pinch. Stein, Wasserman, and MCA decided that they had to get into television production if MCA was to continue expanding, and to do that, the long-standing SAG rule had to go. Although MCA had been granted an occasional waiver from the rule, they now coveted a "blanket waiver" for all productions. They had the admittedly brilliant foresight that MCA could pioneer the filming of television programs that could be resold, as opposed to the live variety emanating from New York.

With Reagan's divorce lawyer Laurence Beilenson representing MCA, SAG began considering the unprecedented blanket waiver. MCA frightened the union's membership by warning that all TV production would stay in New York unless MCA was granted the exemption. Rumors were rife that Sid Korshak was also involved in the dealings on behalf of his friends Lew Wasserman and Reagan. Thus, in his fifth and lame-duck term as SAG president, Ronald Reagan, with his new wife, Nancy, on SAG's board, granted a blanket waiver to MCA on July 14, 1952, allowing Stein's exploding MCA juggernaut a unique immunity from the SAG rules.

Much as James Petrillo's Chicago music-union waivers for MCA had given Stein the advantage in that city, the latest favor gave MCA an insurmountable edge over competing agencies in Hollywood. In the aftermath, MCA, now the only entity capable of "packaging" the product from top to bottom, began to exponentially increase its hold over the entertainment industry. (The company's production income would skyrocket from $8.7 million in 1954 to almost $50 million in 1957, some of which was used to purchase the 327-acre Universal Pictures backlot for $11 million in 1958.) MCA could now demand that outside producers package more MCA talent into a production or take none at all. According to a source for the Justice Department, which began still another investigation of MCA, the mega-agency "has a representative stationed at every studio" who tipped the agency for future negotiations. The result of the spycraft was that if a studio wanted any MCA client (writer, actor, director, singer, comic,.etc.), it had to fill all the positions with MCA clients.12 This dictum extended to nightclubs as well, and businessmen who refused to succumb to the strong-arm tactics were often forced to hire grade B talent. When the Department of Justice investigated MCA for antitrust violations in 1962, it concluded that the 1952 waiver became "the central fact of MCA's whole rise to power."13

Both Hollywood professionals and law enforcement officials were certain that the deal involved collusion between Reagan and MCA. Former MCA executive Berle Adams euphemistically noted, "Lew got close to Reagan on that SAG deal."14 But law enforcement was somewhat less discreet. One Department of Justice source later remarked, "Ronald Reagan is a complete slave of MCA who would do their bidding on anything."15 And although no one in government formally charged that Reagan and MCA had conspired beforehand, many observers assumed that it had happened, especially given what happened next.

The Payback

What added fuel to the Reagan-Wasserman charges was the sudden and dramatic upturn in Reagan's fortunes at MCA. On a small scale, the agency cut a deal for Reagan to work at the Outfit-owned Last Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas to cover, as Reagan himself admitted, his back tax debt. Of considerably more importance was MCA's transfiguring of the washed-up actor into a national television star, a nod that would make Reagan not only a millionaire, but give him an audience that would later be receptive to his increasingly right-wing political aspirations.

A firsthand witness to the accommodation was Henry Denker, a pioneering New York-based television producer for CBS who helmed the weekly dramatic anthology show Medallion Theater, which premiered in 1953. Denker recently spoke of how the shows were put together: "Our advertising agency, BBD&O, asked us to work closely with MCA, because they had the biggest reservoir of stars. 'Work with Taft [Schreiber] and Lew [Wasserman] and Freddie [Fields],' we were told." And MCA delivered, producing such stars as Charlton Heston, Henry Fonda, and Jack Lemmon for Denker.

Occasionally MCA came to Denker asking for a favor in return, usually in the form of adding a new talent they were representing to the cast of the show. Denker had no problem with the quid pro quo, but was quizzical when one MCA request seemed odd: "One day I got a call from Freddie Fields. 'We might get you Ronald Reagan,' he said. Well, I knew by that time Ronald Reagan was over the hill. It was no secret in show business. They said, 'Find something for Reagan to do.' So, I wanted something that was surefire that nobody's ever missed with. I found something that had been produced three or four times—never failed. It was called Alias, Jimmy Valentine, about a safecracker who gets out of jail and decides to go straight. "*

Denker remembered Reagan arriving prepared in New York, adding, "You couldn't have met a nicer guy in your life." At the end of Reagan's yeomanlike performance, a series of events occurred that clarified Freddie Fields's pitch for Reagan. According to Denker, at the end of the live broadcast, the director didn't call for the hot lights to be turned off. Denker thought, "There's something very strange going on here." In a couple of minutes, the situation became odder still when the director had Reagan, who had changed into a suit, stand in front of a gray velour drape and perform the introduction to Alias, Jimmy Valentine—but by now the show was off the air.

"What this really was about came out after the show aired," said Denker, who realized that MCA was using his show and soundstage to film a pilot for a new weekly series that they eventually sold to General Electric. That audition evolved into General Electric Theater, a weekly series for which MCA hired Ronald Reagan at $125,000 per year as host, program supervisor, occasional star, and producer of the show. GE Theater was a top hit, running for nine years.

"I thought about bringing a lawsuit," Denker said years later. "They stole the show. What was going on was they needed a spot for Reagan because it was a payoff for something. They owed him something. This was the payoff for the waiver that he gave to MCA—an incredible conflict of interest. Every favor MCA did, like getting Reagan the GE job, was in exchange for something they got in return. Take my word for it. I know those guys. They were the shrewdest bunch of guys that have ever been in show business, and Lew Wasserman was the top of them all."

Denker later spent a year in Hollywood working at MCA's Universal Pictures production wing, where he saw firsthand why SAG had outlawed the agent-producer role for so long, the rule that was overturned during Reagan's tenure at SAG. "I found out—and here is the real evil in this thing," Denker recalled, "that the Universal writers represented by MCA were being paid less than the writers who are represented by outside agents. They sold their writers down the river."16

In 1972, Denker published one of his thirty-four novels, The Kingmaker, a thinly veiled roman a clef about a superagency that maneuvered one of its actors into the California governor's mansion. In the book, Dr. Isadore Cohen of Chicago creates the Talent Corporation of America (TCA), relocates to Los Angeles, where he lunches at Hillcrest, and promotes a washed-up actor and SAG president, Jeff Jefferson. After passing a SAG waiver for TCA, Jefferson performs in Alias, Jimmy Valentine, and TCA rewards him with the job of hosting the TV show CM Theater. At the end of the book, when a television commentator mused that Jefferson could actually become president of the United States, Cohen recoiled in fear that he might have created a monster. In just eight years, Cohen's fictitious nightmare would become a reality.

"My book is the true story," Denker has said. "I lived through it." True or not, when a prominent Hollywood producer wanted to adapt the book to film, Wasserman put his foot down. "Lew told him, 'Absolutely not!' " remembered Denker.* It would not be the last time that a Supermob boss would interfere with a writer that dared expose their story. MCA's control over so many A-list talents allowed the firm to play hardball over the years with clients whose politics ran counter to Wasserman's and Stein's. In 1954, when SAG again threatened to retract the waiver, Reagan and SAG negotiator John Dales went into closed session and extended MCA's waiver to 1960. "Ronnie Reagan had done Lew another good turn," said Denker.

With Reagan's career back on track, MCA spent the remainder of the fifties building an entertainment monolith. In 1958, the company bought television distribution rights to over 750 pre-1948 films from Paramount Pictures for $35 million. Now MCA could add "distributor" to its list of services. The company also entered into an exclusive relationship with underdog network NBC. Robert Kitner, NBC's vice president, devised the arrangement with his MCA counterpart, Sonny Werblin. "Sonny," Kitner told him, "look at the [NBC] schedule for next season; here are the empty spots, you fill them in."17 By 1959, MCA was producing fourteen NBC shows, for a total of eight and a half hours in prime time.

A potential problem arose in 1959 when SAG's seventeen thousand members threatened their first strike in sixty years, over televised-movie residuals—$60 million of which had already gone to MCA as a result of the Paramount film acquisitions. With their contract with producers scheduled to expire on January 31, 1960, the beleaguered actors prevailed upon SAG board member Reagan to take the SAG presidency again in the mistaken hope that he would provide a strong voice for them in negotiations with MCA. "That's why Reagan was elected president of SAG again in 1959," said a SAG board member. "We knew how close he was to MCA and thought he could get us our best deal."18 (Of particular note was that Reagan was on the board illegally, since he was also a producer of GE Theater. Three years later, Reagan lied to the 1962 grand jury when he said he had not been a producer. Not only have writers for the show recalled his producer role, but Reagan himself admitted it to the Hollywood Reporter for its November 14, 1955, issue.)

SAG rules notwithstanding, Reagan decided to retake the presidency, especially after his Svengali weighed in. "I called my agent, Lew Wasserman," Reagan said. "Lew said he thought I should take the job."19 It is widely believed that Sidney Korshak entered the picture at this point, helping to steer MCA through the shoals of the potentially disastrous SAG negotiations. Then IATSE president Richard Walsh told author Dan Moldea, "Korshak's involved in that whole proposition you're talking about there, and it would tie back into Reagan . . . Reagan was a friend of, talked to, Sidney Korshak, and it would all tie back together . . . I know Sidney Korshak. I know where he comes from, what he is, and what he's done. He's a labor lawyer, as the term goes."20

With Korshak's counsel, Reagan recommended that SAG strike against the producers, but with a twist: MCA would be immune from the strike action. What happened was, Milt Rackmil, president of MCA's production arm, Universal, secretly met with Re and promised that MCA would endow $2.65 million toward an actors' pension fund in exchange for immunity from any work stoppage. Furthermore, in a sweetheart deal that bore all ten fingerprints of Sidney Korshak, SAG would agree to drop its demand for the pre-1960 residuals. After a perfunctory six-week strike, which started on March 7, 1960 (and exempted MCA), the SAG membership agreed to the terms proffered by Rackmil.

MCA's retaining of its huge movie catalog, eventually worth hundreds of millions, dwarfed the $2.65 million donated to the SAG fund. The settlement created a schism in SAG, as some of the membership were overjoyed by the prospect of a pension and welfare fund, while others, especially the older stars of the pre-1960 films, felt as though they had been sold out. "In no way did we win that strike—we lost it," said one member.

As first chronicled by authors and latter-day Supermob gadflies Dan Moldea and Dennis McDougal, a legion of actors went public with their feelings:

• Bob Hope, one of Reagan's closest friends, bitterly stated, "The pictures were sold down the river for a certain amount of money . . . and it was nothing . . . See, I made something like sixty pictures, and my pictures are running on TV all over the world. Who's getting the money for that? The studios. Why aren't we getting some money . . . ? We're talking about thousands and thousands of dollars, and Jules Stein walked in and paid fifty million dollars for Paramount's pre-1948 library of films and bought them for MCA . . . He got his money back in about two years, and now they own all those pictures."

• Gary Merrill: "Reagan sold us down the river."

• Gene Kelly: "Reagan didn't pump for residuals at all."

• June Lockhart: "Reagan and MCA sold us out."

• Mickey Rooney was among the most passionate when he said, "The crime of showing our pictures on TV without paying us residuals is perpetuated every day and every night and every minute throughout the United States and the world. The studios own your blood, your body, and can show your pictures on the moon, and you've lost all your rights. They own you, and they own the photoplay. We're not human beings, we're just a piece of meat."21

Two months after "The Great Giveaway," and with SAG members calling for his resignation, Reagan suddenly remembered that he could not legally hold the SAG presidency since he was also a 25 percent owner and occasional producer of General Electric Theater. Reagan resigned his post on June 6 and quit the SAG board on July 11. At the time, Reagan said, "I know I came back for a purpose, and it's been accomplished."

Over the next few years, Ronald Reagan cashed in on his GE Theater while becoming more politically active and increasingly conservative. In 1960, Reagan supported Republican presidential candidate, and fellow red-baiter, Richard Nixon, warning that the Communist Party "has ordered once again the infiltration" of the movie industry. "They are crawling out from under the rocks," Reagan intoned.

While Wasserman and Stein nurtured the career of Ronald Reagan, fellow Supermob associate Paul Ziffren was seeing to it that the former Chicagoans were well entrenched with the state's Democratic up-and-comers. In 1958, Ziffren backed his brother's boss, and Korshak's friend, California attorney general Pat Brown, in his gubernatorial run against incumbent Republican senator William Knowland, scion of the Joseph Know-land Oakland Tribune empire. To this end, Ziffren formed the highly secretive Southern California Sponsoring Committee, unregistered with any state regulatory agency. Ziffren told one wealthy Democrat that the idea was to enlist one thousand of his friends to donate $1,000 each, and to function as an emergency fund for the Democratic Party. The group opened an account in Al Hart's City National Bank in Beverly Hills.

That year, Sid Korshak was observed in a meeting with Ziffren at the home of actress Rhonda Fleming, known to have been very close to Sidney. Also participating was Superior Court judge Stanley Mosk, a University of Chicago graduate.22 The purpose of the meeting was unknown at the time, but would become obvious soon after the election.

Although Ziffren raised eyebrows with his secretive sponsoring committee, Brown's opponent, Knowland, sank even lower and attempted to tarnish Brown in a classic "guilt by association" charge—an association with Ziffren, to be exact. To understand how Knowland would be aware of Ziffren's associates, it is first necessary to scrutinize Knowland's. Know-land was a political bedfellow of Richard Nixon's, and the two shared the friendship of Beverly Hills attorney Murray Chotiner, who had, at age thirty-three, masterminded Earl Warren's campaign for the governorship and Nixon's 1950 congressional bid. In that contest, Nixon smeared opponent Helen Gahagan Douglas with red-baiting charges that often appeared in the form of flyers written by Chotiner. Knowland repeatedly sparred with Nixon over who was the most aggressive commie fighter.

Paul Ziffren (Library of Congress)

By definition a member of America's Supermob, Chotiner specialized in representing underworld types, such as Pennsylvania Mafia boss Marco "the Little Guy" Reginelli, and Angelo "Gyp" DeCarlo, in their legal battles with the feds. As might be expected, the two Beverly Hills attorneys Korshak and Chotiner were close friends, with Marshall Korshak telling a friend, "Every client Chotiner had, he first checked out with Sidney."23 Interestingly, Chotiner, the son of a Pittsburgh cigar maker, and Sid Korshak shared the friendship of New York lobbyist Nathan Voloshen, who in turn was close to future Speaker of the House John McCormack.24 Through Korshak's New York associate George Scalise, Voloshen obtained underworld clients such as Salvatore Granello, Manuel Bello, and Anthony DeCarlo.25

As mentor to both Nixon and Knowland, Chotiner toured the country in 1955, giving secret lectures to GOP "political schools" at the request of the Republican National Committee. A copy of the Chotiner lecture was leaked to the Democrats, one of whom described the transcript as "probably one of the most cynical political documents published since Machiavelli's The Prince or Hitler's Mein Kampf, . . . a textbook on how to hook suckers."

Not long after Chotiner became Knowland's campaign manager, Know-land came into possession of real estate records linking Pat Brown's backer Paul Ziffren to Alex Greenberg, Sam Genis, and the rest of Chicago's underworld. With Chotiner's unsavory connections, it is likely that Know-land had inside information on the deals. It is also possible that the damning material came from journalist Robert Goe, who was eager to expose the Arvey-Ziffren infiltration of the state.

In the campaign, Knowland attacked Brown's keystone supporter Ziffren with the Capone-Greenberg, Hayward Hotel, and Seneca connections, etc.

Although there was no evidence that Pat Brown had knowledge of or condoned Ziffren's business partnerships, Knowland tried to make the mud stick. In speeches widely covered by California newspapers, Knowland warned of "the existence in California of a shadowland powerful force infiltrating our political and economic life." He called it "an overworld." (Compounding the bad news that year for Ziffren was word from Chicago that in November 1958, after a two-and-a-half-year investigation, Ziffren's forty-one- year-old brother, Herman, was arrested in Illinois on three counts of violating the White Slavery Traffic Act. Specifically he was charged with transporting three women across state lines for immoral purposes. Fifteen months later he received a $4,000 fine.)26

Of course, Knowland was correct about what Ziffren was pulling off, even though Brown may not have realized it. Veteran New York Times L.A. Bureau chief and California political scholar Gladwin Hill pointed out, "Whatever his shortcomings, Knowland was given neither to falsehood nor to gratuitous aspersion."27 For his part, Ziffren called the charges "scurrilous nonsense" and implied that Knowland was anti-Semitic.28

After the Knowland charges appeared in the press, the FBI's L.A. Field Office opened what would become a 386-page file on Paul Ziffren. The file, which remained open for five years, represented a compendium of allegations against Ziffren, with virtually no editorializing, and no conclusions made by Bureau headquarters. There was no indication that the material was forwarded to the Department of Justice for action.

Knowland's attack on Brown had little impact, but the senator's antiunion, pro open shop (right-to-work) platform infuriated organized labor. In addition, Knowland's wife (known as the Martha Mitchell of the sixties' *) sent a caustic seven-page letter to two hundred Republican leaders throughout the state, calling organized labor "a socialist monster." Thus it was no surprise when Brown won the election by a huge 20 percent margin, with over five million votes cast. It was a momentous win for the revitalized Democratic Party, which captured not only the governorship for the first time in twenty years, but both houses of the legislature for the first time in seventy-five years. For Knowland, the defeat initiated a long downward spiral, both professionally and personally. When Knowland's wife, Ann, initiated divorce proceedings in 1972, she threatened to hire Paul Ziffren as her representative. "He hates your guts," Ann told Knowland.29 The 1958 defeat also gave Nixon sole claim to the state's red-baiting pedagogy, making him the official right-wing standard-bearer from California*

Governor Brown quickly appointed Judge Mosk, the man who had recently huddled with Ziffren and Korshak, as attorney general. The Los Angeles Mirror editorialized that Mosk would never have become AG "were it not for the strength he gained from Paul Ziffren."30 The FBI echoed the conclusion when it noted in Ziffren's file that "[Mosk] owed his job at least in part to the genius of Ziffren."

Despite his candidate's winning the governorship, Paul Ziffren was still dogged by Knowland's Supermob allegations. On April 20, 1959, when Ziffren, in his capacity as the California Democratic national committeeman, lobbied in Sacramento for bills that would place stricter regulations on police arrest procedures, he was questioned in the open legislature about his Capone affiliations. One senator intoned, "I don't intend to let the Capone mob tell us how to write a law of arrest. I think we're entitled to know where these bills came from and who's behind them." Ziffren's only reply was "My own background has nothing to do with the merit of these bills."31

To the press, Ziffren said it was "ghoulish" to bring up the names of his business partners. (Greenberg had already been gunned to death, and Evans was about to be. On August 22, 1959, Evans was shot to death in Chicago, and typically for that city, no one was ever charged. At his probate hearing, it was estimated that his nonliquid real estate holdings approached $11 million.)

"I don't believe in character assassination," Ziffren informed the media. "Greenberg was honorable in all the dealings I had with him."32 Ziffren also pleaded ignorance of what Evans's and Greenberg's underworld connections might have been. This contention borders on the ludicrous for numerous reasons: Ziffren's mentor, Arvey, was Greenberg's longtime partner in Lawndale Enterprises; Ziffren's college classmate, best friend, investment partner, and law partner, David Bazelon, had helped in the tax case against Greenberg's investment client Frank Nitti and handled Greenberg's Canadian Ace Brewery legal affairs; the longtime cohort of Ziffren's partner Fred Evans, Murray Humphreys, was Public Enemy Number One in the 1930s, and their indictment for embezzling the Bartenders Union out of $350,000 was front-page news in Chicago just a few years before the Hayward purchase, while Ziffren and his firm were Greenberg's tax lawyers; Greenberg's mob ties were well-known to the U.S. Attorney's Office, where Ziffren previously worked; Ziffren's partner in Store Enterprises, Sam Genis, was a convicted check kiter and associate of Lansky, Zwillman, and Costello; at the Lansky infiltrated Kirkeby-Nacional organization, Paul and Leo Ziffren handled legal matters, while their executive secretaries sat on the board, and Paul's brother-in-law was the VP of the company; lastly, Ziffren was Greenberg's tax attorney at Gottlieb and Schwartz, filing returns that showed his payments to Evans—this was in 1943, when Greenberg paid Ziffren for help in dealing with Greenberg's being implicated in the massive front-page-news Hollywood extortion scheme by the Capone mob.

Considering that Ziffren was an unquestioned genius in both tax law and investing, it strains credulity that he was unaware of the connections of his numerous tainted partners.

Despite the allegations, Ziffren's power was at such a zenith that he was able to accomplish the unthinkable, convincing the Democratic National Committee to hold their 1960 presidential convention in Los Angeles, wresting it from the proponents of favored cities including Chicago, where Jake Arvey lobbied for the event. With this move, Ziffren was stepping out from Arvey's shadow once and for all, letting it be known that he was now an independent kingmaker.

In recognition of Ziffren's contributions to the party, the California Democratic Committee rewarded him with a fete in his honor at Arnold Kirkeby's Beverly Hilton Hotel on June 23, 1959. Among the two thousand in attendance were a sponsoring committee that included all the partners (except for Bazelon) in the L.A. Warehouse Company, Sidney Korshak, Eugene Wyman, and Jonie Tapps (a producer pal of Johnny Rosselli's). In the festivities, Ziffren was saluted by Stanley Mosk and regaled by a performance from Korshak's great friend Rhonda Fleming.

The glow would not last long. The gala at the Beverly Hilton masked a growing tension in the Brown-Ziffren camp. Ziffren was becoming a lightning rod for controversy, and while he had undeniably played a huge role in the Democratic Party's resurgence, not all party faithful sang his praises. "I dislike him with a passion," said one Democratic legislative leader.33

Not long after his election, Governor Brown started to distance himself from Ziffren, warning him to not take credit for the election. "I am the architect of my own campaign," Brown told local scribes. In part motivated by Brown's desire to avoid contamination with the Greenberg deals, the rift would last years and lead to Ziffren's retirement from the Democratic Committee's top post. Brown, however, felt no such need to part company with Sid Korshak, since the Fixer was virtually unknown to the public at large.

Not only were they frequently seen dining together, but also, according to some, were making critical state government decisions. Dick Brenneman, who developed well-placed sources when he investigated Korshak for the Sacramento Bee, was informed by a judicial source that Brown had convened with Korshak since the early fifties at Harry Karl's mansion (which Korshak later purchased) on Chalon Road in Bel-Air. According to the source, one purpose of the meetings was for Brown to vet his judicial appointments with Korshak.34 Brenneman was further told by LAPD lieutenant Marion Phillips, who often surveilled the Korshak crowd for LAPD intel chief Jim Hamilton, that there were also numerous such Brown-Korshak huddles at Chez Karl.

In January 1960, Attorney General Mosk announced his intent to go after white-collar crime, especially in real estate investment. The implications of such a probe were not lost on knowledgeable California journalists, who knew that such a crusade by Mosk would likely expose the Ziffren-Greenberg nexus. As the Hollywood Citizen News wrote, "If Attorney General Mosk isn't careful, he may find himself soon treading on the toes of his political mentor, California National Committeeman Paul Ziffren, whose phenomenal economic penetration of California and criminal affiliation is a matter of record. 35

Circumstantial evidence suggests that Ziffren may later have acted to short-circuit Mosk's agenda in 1964, when Mosk was the presumed Democratic front-runner in the California senatorial race—and yet mysteriously dropped out of the contest that spring. Thirty years later, in a 1994 cover story in the L.A. Weekly, Charles Rappleye and David Robb reported that Mosk's sudden exit was the direct consequence of an extramarital affair he'd been having with a young woman deeply involved in the world of organized crime. Chief William Parker's LAPD had reportedly come into possession of compromising photos of Mosk and the young woman. Interestingly, the LAPD's files reference Ziffren's own dalliances with hookers. Connie Carlson, one of Mosk's most trusted investigators in the AG's office, recently said, "Mrs. Edna Mosk told me about how Ziffren tried to block Mosk's advancement."*36

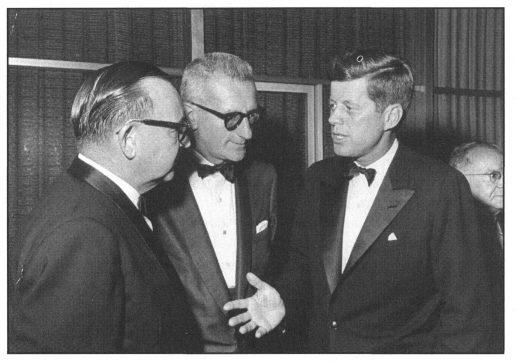

Edmund "Pat" Brown, Paul Ziffren, and John F. Kennedy during the 1960 presidential campaign (TimeLife)

Brown's people also accused Ziffren of having tried to persuade Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy to run in the California primaries against "favorite son" Brown. (Kennedy, a well-known pal of the Vegas Supermob, told an adviser that support from Ziffren and his Democrats was critical to his presidential ambitions.)37 Finally, on June 19, 1960, the party's delegates voted 115 to 3 to replace Ziffren as party chairman. Stanley Mosk was voted to replace him. It had been rumored that Brown promised Mosk the state's Supreme Court chief justice post if he would go up against Ziffren.* The press interpreted Ziffren's defeat as a big victory for the governor, "who had gone all out to oust the incumbent committeeman. It ended a bitter fight which has torn the Democratic ranks, particularly in Southern California." 38 Another paper ran an editorial stating, "Last Saturday the chickens came home to roost."39

When Mosk stepped down from his Democratic National Committee post in 1961, he was replaced by yet another Chicago-born attorney, Eugene Wyman, Greg Bautzer's law partner. As chairman, Wyman proceeded to entice contributions to the party from his closest well-heeled pals, chief among them Al Hart, Jake "the Barber" Factor, and Sid Korshak. All were said to be major contributors, although Korshak rarely gave in his own name. "He had to do something with all that cash!" remarked one friend.40

As if to rub salt in Ziffren's wounds, perennial Supermob gadfly Lester Velie weighed in once again. In the July 1960 issue of Reader's Digest, Velie launched a broadside at Ziffren entitled "Paul Ziffren: The Democrats' Man of Mystery." In the biting seven-page article, Velie not only surfaced Robert Goe's research about Ziffren's fronting for the Capones via Greenberg, but he worried how much influence the mob would have in the White House if a Democrat supported by Ziffren won in 1960. One did, and the mob was happy to help him get elected. After Kennedy's July 11, 1960, nomination in L.A., Ziffren's lawyer Isaac Pacht was alleged to be preparing a libel complaint against Velie.41 Sid Korshak's advice was also sought out, and he was said to have remarked to a friend, "Paul is always getting himself into hot water and I have to pull him out."42

When the FBI learned that Velie was about to excoriate Ziffren, the SAC of the L.A. Field Office wrote Hoover, "The big question is will Velie's piece destroy Ziffren or will the public remain as apathetic as it did when gubernatorial candidate William Knowland attempted an expose in November 1958 ?"43 The SAC went even further when assessing the Democratic Party rift caused by the Ziffren revelations: "Ziffren, hoodlum-founded though he is, is probably the shrewdest, most cunning, far-sighted, behind-the-scenes political manipulator ever encountered in California—where kingmakers have historically ruled politicians."44

Meanwhile, in D.C, an unnamed political journalist informed an FBI pal that David Bazelon was being groomed to be nominated to replace Judge Felix Frankfurter on the U.S. Supreme Court.45That would turn out to be the case after the upcoming presidential election. At the same time, the City of Los Angeles was feathering Bazelon's financial nest: reportedly due to the influence of Paul Ziffren, the city purchased the massive Warehouse Properties parcel for $1.1 million in furtherance of its Civic Center Master Plan. The lot was situated in the center of a location earmarked for purchase by the federal government for the new $30 million Customs Building. Leo Ziffren had also been seen massaging the deal in the office of the city's chief of the Bureau of Right of Way and Land.46 Bazelon's cut was over $100,000. 47

Paul Ziffren began spending more time expanding his law practice, specializing in tax and divorce law and representing numerous Los Angeles celebrities and moguls. He was regularly seen driving around Beverly Hills in his silver Rolls-Royce, at a time when they weren't nearly as ubiquitous as they are now in the affluent city.

*In fact, MCA had been breaking the rule for at least two years, producing such television programs as Your Hit Parade, Starring Boris Karloff, Stars over Hollywood, and The Adventures of Kit Carson.

*Denker described the surefire plot thus: "Valentine, the former safecracker, gets a job in a small town and everything is fine, and the banker's daughter falls in love with him. And everything is just going great until one day when the banker's young son got stuck in the timed walk-in vault. And the only person who can open that vault before the oxygen runs out is the ex-safecracker Jimmy Valentine. But he has to expose his past and lose the girl to save the kid. So he opens the safe—great finish."

*After moving back to New York, Denker produced six plays on Broadway, two for the Kennedy Center, and published thirty-four novels, with more titles chosen by Reader's Digest Book Club than by any other author.

*Martha Mitchell, the wife of President Nixon's attorney general John Mitchell, became infamous for her unbridled media outbursts.

*Knowland went back to Oakland, where he took over his father's Oakland Tribune, but quickly fell into debt and depression. Ironically, much of the debt was incurred in Las Vegas at the Supermob's Riviera, Tropicana, and Stardust casinos. On February 17, 1974, he committed suicide by means of a ,32-caliber Colt automatic.

*In the 1964 senatorial race, two sources—one of them a prominent Democratic newspaper publisher—told the Weekly that Democratic state comptroller Alan Cranston had shown them those photos in the spring of 1964 in an effort to get Mosk to drop from the race. Cranston said their memory was playing tricks on them.

*In 1964, as predicted, Brown appointed Mosk chief justice of the California Supreme Court, where he would serve for a record thirty-seven years. Writing over fifteen hundred decisions, he was rightly called "one of the most influential figures in the history of California law."