By 1960, Korshak's influence surged beneath the surface of Hollywood like an underground river.

DENNIS MCDOUGAL, AUTHOR AND EXPERT ON HOLLYWOOD HISTORY1

WITH REAGAN, WASSERMAN, STEIN, Hart, and Ziffren moving fast to create a Supermob-friendly California, Sid Korshak, Moe Dalitz, and Jake Factor saw to it that Las Vegas similarly reflected the wishes of the cadre and its even less savory partners. The city in the desert was exploding, thanks to the massive cash infusion from the Teamsters Pension Fund, and the Eastern gangs that created it were realizing their dream of going legit (or semi-legit), with the contingent from Kiev handling the paperwork. Additionally, Kennedy family patriarch Joe Kennedy had numerous investments in the state, and his presidential candidate son Jack was considered an honorary member of Sinatra's Rat Pack, which was ensconced in Sinatra's Sands and Korshak's Riviera in January-February 1960 while filming Ocean's Eleven.*

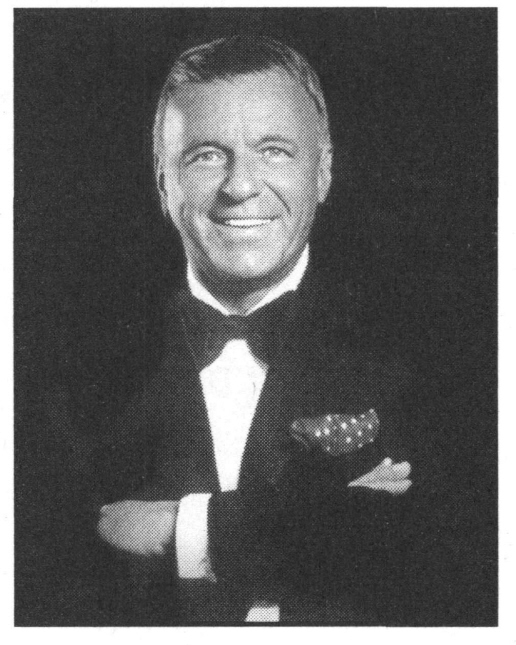

Sinatra's official Riviera portrait (courtesy John Neeland, the Riviera)

When the Pack sobered up in the Sands steam room after an all-nighter, Jack Kennedy often joined them, wearing his bathrobe, a gift from Sinatra, embroidered with his Pack nickname, Chicky Baby.

"We practically considered Jack to be one of the boys," one erstwhile Chicago Outfit associate recently said. For decades a handwritten note from Jack hung in Sinatra's "Kennedy Room" in the Voice's Palm Springs home (later redecorated by Bee Korshak), reflecting Kennedy's reliance on Sin City in the upcoming contest. "Frank," the barely legible scrawl began, "How much can we expect from the boys in Vegas? [signed] JFK."2 He got plenty. In addition to massive "anonymous" Vegas donations, Jacqueline Kennedy's uncle, Norman Biltz, who built Kennedy's Cal-Neva Lodge in 1926, traipsed up and down the Vegas Strip collecting some $15 million from "the boys" for Jack's war chest.3 The Stardust's Jake Factor contributed $22,000 to the campaign, becoming JFK's single largest campaign contributor.4

The Supermob's Fear Factor

There was, however, one storm cloud looming that threatened to spoil the elysian setup: Jake Factor's nemesis Roger Touhy had just been released (in November 1959) from his wrongful twenty-seven-year incarceration for Factor's "kidnapping"—and he wanted payback*

Touhy published his autobiography, The Stolen Years (written with veteran Chicago crime reporter Ray Brennan), simultaneous with his release from prison, prompting Chicago boss Accardo to make certain that Teamster truckers refused to ship the book, and Chicago bookstores were frightened off from carrying the memoir. Undeterred, Touhy also announced that he intended to sue Factor, Sid Korshak's Chicago point man Tom Courtney, Korshak's mentor Curly Humphreys, and Accardo for $300 million for wrongful imprisonment.

The threat couldn't have come at a worse time. Stardust front Factor, the man most directly vulnerable to Touhy's offensive, was in the midst of a massive and determined reputation face-lift. Since the midfifties, Factor had been drawing on the great fortune he had amassed during his early British stock swindle to embark on a successful PR campaign aimed at creating the persona of Jake the Philanthropist. With the Stardust humming along, Factor dabbled in California real estate and life insurance, exponentially increasing his wealth. His frequent six-figure donations to various charities earned him numerous humanitarian awards. The Barber/Philanthropist was simultaneously engaged in a seven-year battle to obtain a presidential pardon for his crimes, most of which he never served time for.* This was at the same time that the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was considering deporting Factor back to England to face the massive mail fraud charges brought against him decades earlier.

Faced with a noisy Touhy threatening to expose the entire Vegas-California enterprise, Jake Factor hired Korshak to prepare a countersuit.5 But with so much riding on the outcome, a decision was quickly reached that Touhy had to be dealt with in a way much more permanent than a time-consuming lawsuit. Thus, on December 16, 1959, just three weeks after his emancipation, Roger Touhy was murdered with five shotgun blasts, while Jake Factor dined at the Outfit's Singapore Restaurant in Chicago. The Chicago Daily News reported two days later, "Police have been informed that the tough-talking Touhy had given Humphreys . . . this ultimatum: 'Cut me in or you'll be in trouble. I'll talk!" On his deathbed, the former gangster whispered, "I've been expecting it. The bastards never forget." Not long after, Factor sold Curly Humphreys four hundred shares of First National Life Insurance stock at $20 a share, then bought them back after a few more months for $125 per share. Curly netted a tidy $42,000 profit. Insiders concluded this was a gift to Curly for arranging Touhy's murder.

Factor was questioned under oath by suspicious IRS agents in Los Angeles, and he explained that he had suddenly decided, after twenty-seven years, to pay Humphreys for assisting in the release of his "kidnapped" son, Jerome, not the recent slaying of his nemesis.6

With Touhy removed, Factor was free to lobby for his presidential pardon and to fight the INS deportation threat. Showing great audacity, Factor had none other than Al Hart attest to his rehabilitation. The FBI interviewed Hart on July 6, 1960, and he informed the Bureau that "[Factor] is endeavoring to live down the past." Hart added that Factor contributed to many charities and that he would "highly recommend him for a pardon." Even Estes Kefauver wrote a letter on Factor's behalf. Also backing Factor's pardon were Korshak pals California governor Pat Brown and Republican senator Thomas Kuchel.7 The effort dragged on for two more years before a decision was reached.

Interestingly, while Factor was trying to burnish his image with the feds, he was simultaneously involved with Jimmy Hoffa in a Florida land deal that would, years later, see Hoffa eventually imprisoned. In May 1960, according to the sworn testimony of a witness, Factor lent $125,000 to a partner in Florida's Sun Valley housing development, later found to have diverted $1.7 million from its Teamsters Pension Fund loan to the partners' own bank accounts. But this transaction was not discovered until 1964, allowing Factor more time to once again escape extradition.8

With Jack Kennedy now occupying the Oval Office, the country was in the midst of Robert Kennedy's stewardship of the Department of Justice. For years, Korshak's relationship with G-men had been polite in the extreme; however, after Robert Kennedy declared war on the underworld, Korshak became irritated by the nuisance it was becoming. In the summer of 1961, Korshak informed a Chicago FBI agent, "I believe your organization has forfeited all right to talk to me." He explained that he believed the FBI was opening an investigation of him.9 Korshak also likely learned that the Nevada Gaming Control Board was inquiring about him to the Chicago Crime Commission. In a letter to the CCC, the Control Board's chief investigator, Robert Moore, had asked Director Virgil Peterson for information about recent Las Vegas arrivals from Chicago. In addition to Korshak, the other names on the list were Joseph and Rocco Fischetti, Frank Ferraro, Gus Alex, Louis Kanne, Murray Humphreys, John Drew, Tony Accardo, and Sam Giancana.10

Whereas the Supermob and their mob associates felt beleaguered in Chicago, they continued to enjoy virtual immunity in sunny California, where Korshak was now Hollywood royalty, reporting earnings of $500,000 per year. That figure was fallacious, since he often demanded payment in cash and confided to friends that his income was $2 million plus. His FBI case officer called him "possibly the highest-paid lawyer in the world." Amazingly, on his 1961 home insurance policy Korshak claimed to be "semi-retired." Among his circle of friends, Korshak was beginning to get the reputation of a mensch, freely giving money to those in a jam, and spending lavishly on gifts that the more cynical observers could assume were a tad shy of meeting the altruistic ideal. In 1961, for example, he purchased one thousand seats for friends and business contacts for the first heavyweight fight ever held in Vegas.

Korshak's labor-mediating prowess was now being spoken of, if in hushed tones, in boardrooms from coast to coast. As his stature rose in the eyes of big business, he became the go-to man for entrepreneurs in even the most unconventional professions. One of Sid Korshak's labor "consultancies" in 1961 was widely believed by authorities to have included his brother Marshall in a bribery scheme aimed at one of Chicago's fastest-rising stars, Hugh Hefner, the chairman of Playboy Inc. At the time, the thirty-five-year-old Hefner presided over an empire built around his monthly magazine, Playboy, which was itself built on the attributes of the stomach-stapled, airbrushed Playmates that appeared in the magazine's gatefold. Complementing the magazine at the time were four "key clubs" in Chicago, Miami, New Orleans, and St. Louis, which, by 1961, were grossing a combined $4.5 million per year. In the flagship Chicago club on 116 E. Walton Street in the posh Near North district, Hef 's bunnies mingled with "keyholders," many of whom represented the upper echelons of the Chicago Outfit and Supermob.

Of course, it was impossible for a successful Chicago club to avoid the fingerprints of the smothering Chicago underworld, and the Playboy Club was no exception. Among the 106,000 Chicago keyholders were Sam Giancana, Joseph Di Varco, Gus Zapas, and the Buccieri brothers; Outfit bosses were bestowed exclusive Number One Keys, which allowed them to date the otherwise off-limits "Bunnies" and to drink on a free tab. Slot king, and Humphreys's crony, Eddie Vogel dated "Bunny Mother" Peg Strak.

As with most other Near North businesses, the Playboy Club had to make accommodations with the countless semilegit enterprises within the all-encompassing grasp of the Chicago Outfit. In addition to the army of hoods cavorting at the new jazz-inflected boite, the mob's business arm controlled the club's numerous concessions—bartenders, waiters, coat checkers, parking valets, jukeboxes—so vital to the new enterprise. The intersections started with Hef 's liquor license, which had to be approved by the Outfit-controlled First Ward Headquarters, where John D'Arco and Pat Marcy reigned supreme. It was said that much of the club's cutlery was supplied by businesses owned by Al Capone's brother, Ralph, while other furnishings had their origin in the gang's distribution warehouses. Local bands that supplied the requisite cool-jazz backdrop were booked either by James Petrillo's musicians union or by Jules Stein's MCA.

Victor Lownes III, who oversaw the Playboy clubs, explained the obvious: "If the mob runs the only laundry service in town, what are we supposed to do? Let our members sit at tables covered with filthy linen?"11

Coordinating the gang's feeding frenzy was the club's general manager, Tony Roma (of later restaurant fame), who was married to Josephine Costello, daughter of Capone bootlegger Joseph Costello. Roma was also an intermediary for certain Teamsters Pension Fund loans. One IRS agent noted his "associations with organized crime figures in Canada," while another stated, "I think it's more accurate to say Roma's a trusted courier, probably of money and messages, for the likes of [Meyer] Lansky."12 Chicago crime historian Ovid Demaris described how Roma operated the Chicago Playboy Club: "One of Roma's first acts as general manager of the Chicago Playboy Club was to award the garbage collection to Willie 'Potatoes' Daddano's West Suburban Scavenger Service . . . Attendant Service Corporation, a [Ross] Prio-[Joseph] DiVarco enterprise, was already parking playboy cars, checking playboy hats and handing playboy towels in the restroom. Other playboys were drinking [Joe] Fusco beers and liquors, eating [James] Allegretti meat, and smoking [Eddie] Vogel cigarettes."13

Eddie Vogel's girlfriend, "Bunny Mother" Peg Strak, became Roma's executive secretary when Roma was promoted to operations manager of Playboy Clubs International Inc., which oversaw the empire of sixty-three thousand international keyholders.

When Hefner and Lownes began planning in 1960 for an inevitable club in Manhattan, they ran into a stubborn State Liquor Authority (SLA), which was known for withholding the requisite liquor license without a "gratuity" being offered to its chairman, Martin Epstein. After having purchased a six-story former art gallery on pricey Fifty-ninth Street, east of Fifth Avenue, not far from Sid Korshak's office at the Carlyle, Playboy waited for the license. But by the fall of 1961, with thousands of keys in advance of a December 8, 1961, scheduled opening, the document had yet to arrive.

According to the Chicago Crime Commission, Playboy simultaneously contacted the Korshaks for advice, noting, "Sidney and Marshall Korshak had been approached by Playboy as to how to obtain a New York liquor license." 14 Hefner was well acquainted with the talents of the Korshak brothers through his friend Erie Melvin Korshak, another attorney and a cousin of Sidney and Marshall's. Previously, when his fledgling magazine faced an obscenity charge due to a nude model draped in an American flag, Sidney recommended that Hef engage Marshall, who quickly had the case quashed.

Now, in regard to the license, a Capone hood named Ralph Berger* showed up at Playboy's Chicago office to inform Hefner and Lownes that he could break the stalemate. According to the FBI, Berger, who lived in the Seneca and frequented the Korshak brothers' office at 134 N. LaSalle, had been instructed by the Korshaks to make the overture. For years, Marshall had been an official of Windy City Liquor distributors, and the FBI stated, "Berger was the contact man between Korshak and . . . the chairman of the Illinois Liquor Control Board." Korshak also developed associations with New York's SLA. In fact, he and Berger had previously performed the same "service" for New York's Gaslight Club.15

Playboy agreed to pay Berger $5,000 to represent them to the New York authorities, and when his fee did not arrive promptly, Berger, according to his later testimony, called Marshall Korshak, who made it happen. Epstein arranged for Hefner and Lownes to meet with him at the SLA office in New York. When they arrived at the building, they saw a protester outside with a placard that read THE STATE LIQUOR AUTHORITY IS CROOKED AND CORRUPT. Lownes later said, "By the time we came out, I felt like joining him." At the meeting, SLA chairman Epstein asked for $50,000 for the license. And there was more: in subsequent meetings, Playboy was informed that the New York Republican state chairman and aide to Governor Nelson Rockefeller, L. Judson Morhouse, wanted $100,000 plus the lucrative concessions in all the Playboy clubs' gift shops in exchange for his help.

After protracted negotiations throughout the fall of 1961, Epstein eventually settled for $25,000, and Morhouse, $18,000. When the officials were finally placated, the precious certificate arrived just hours before the December 8 opening. However, the fix became unraveled during a grand jury proceeding looking into corruption at the SLA. Eventually, Berger was charged with conspiracy to bribe Epstein and received one year in prison. Epstein was considered too old (seventy-five) and infirm to be charged. Morhouse was also convicted but saw his prison sentence commuted due to his poor health. No one at Playboy was charged; neither were the Korshaks, despite their being named in the testimony.16

The FBI summarized, "If Berger was able to exert any influence with certain members of the State Liquor Authority [SLA] . . . he undoubtedly would do so as a representative of the Korshaks and not in his own right. It was believed that any conniving Berger might do with the New York SLA or with the Illinois State Liquor Control Board would be done on behalf of and under the instructions of the Korshak brothers."17

Despite the embarrassment, Hefner was obviously satisfied with the performance of Sid Korshak; years later, Hefner would again engage the services of Korshak, who, for a $50,000 fee, attempted in vain to settle a film copyright case with Universal Studios, which was run by his old friend Lew Wasserman.

Success followed success for Korshak. Typically, his triumphs were unknown to the public at large, who were nonetheless affected by them in ways large and small. In Los Angeles, he staved off labor strikes at area racetracks, where the Teamster-dominated culinary workers could bring an operation to its knees. When Hollywood Park Racetrack was hit with a work stoppage by the Pari-Mutuel Clerk Union in 1960, Korshak's Hillcrest friend and Hollywood Park Racing Association president Mervyn LeRoy enlisted Korshak to address the stalemate that twenty-eight previous lawyers couldn't resolve. Betsy Duncan Hammes, one of Johnny Rosselli's lady friends, recently recalled how it occurred: "Mervyn LeRoy called me and asked me to call Sidney and ask him to call the Hollywood Park strike off," said Hammes. "So I called Sid, and he said, 'Don't worry, you can go on Monday' "18 As promised, the Fixer settled it in forty-eight hours, somehow convincing the strikers to accept another sweetheart contract. In December 1960, Korshak settled his first labor dispute for Santa Anita Race Track in Arcadia, when employees threatened a walkout. According to an FBI source, Korshak received "interest in the racetrack" as his fee.19

One Korshak power play with Chicago racetrack labor would have repercussions over the next two decades. By 1960, Ben Lindheimer was the acknowledged sachem of Chicago-area racing, owning the two thoroughbred tracks Arlington Park and Washington Park under the banner of Chicago Thoroughbred Enterprises (CTE). Lindheimer was a well-known reformer and outspoken opponent of the Chicago Outfit's attempts to infiltrate his operation. Exacerbating the bad blood was the fact that Lindheimer was an assimilated German Jew with an inbred dislike of Russians like Korshak. Nonetheless, he could do little about the mob-connected unions that plied their trades in the parking lots and elsewhere (or the fact that Jake Arvey owned six thousand shares of stock in Arlington),20 but he drew the line at allowing convicted hoods onto the racing grounds; one of Sid Korshak's Outfit mentors, Jake Guzik, was barred for life from Lindheimer's CTE tracks.

However, on Sunday morning, June 5,1960, when the Korshak-represented mutuel clerks threatened a strike at Washington Park, an extremely ill Lindheimer was forced to deal with the devil: he immediately called Korshak to ask that he avert the work action. But this time Korshak took the union's side against the antimob track owner and allowed them to walk off the job. That same night, Ben Lindheimer died of a heart attack. His stepdaughter Marge Lindheimer Everett, who inherited her stepfather's empire, blamed Korshak for her father's death and fired him after she took over. "We'd never had a strike before, never," Everett later said. "I think it killed him."21 After later moving to Beverly Hills (a move believed to be influenced by the similar relocation of her great childhood friend, Nancy Davis Reagan), Marge Everett told the Bistro's Kurt Niklas about what she believed Korshak had done: "He killed my father by refusing to call off the strike. All Korshak had to do was pick up the telephone, but he didn't. As far as I'm concerned, it was the same as murder."22 It would be the beginning of a lifelong feud between Marge Everett and Sid Korshak.23

Another sports venue became part of Korshak lore when he made certain that an important new L.A. sports franchise got off to a smooth start. Soon after his election, Governor Pat Brown, Korshak's pal in the statehouse, pledged to sell thirty-six acres in L.A.'s Chavez Ravine tract to the city in furtherance of the plans of Walter O'Malley, who had just relocated his Brooklyn Dodgers to the West Coast. O'Malley was determined to build his dream baseball stadium, and that enterprise hung on the upcoming referendum known as Prop B. Just prior to the vote, on June 1, 1958, the Dodgers aired a live, five-hour "Dodgerthon" from the airport as the Dodger team plane arrived from the East. Helping O'Malley extol the virtues of Prop B were numerous celebrity associates of Korshak/Ziffren/Brown, including Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Ronald Reagan, and Debbie Reynolds. Two days later, the referendum narrowly passed (351,683-325,898) and was immediately appealed (all the way up to the Supreme Court) on the grounds that the city's granting of the land use did not follow a "public purpose" clause in the federal government sale to the city. When the high court finally dismissed the appeal on October 19, 1959, the state began evicting squatters who lived in the ravine, and ground was broken for Dodger Stadium.24

By the time of the April 10, 1962, opening day, O'Malley had, not surprisingly, engaged Sid Korshak as his $100,000-per-year labor consultant, responsible for keeping the cars parked, the lights on, and the food service employees behind the concession stands. When it came to parking, Korshak had a special influence, as that concession was awarded to a Nevada corporation, Concessionaire Affiliated Parking Inc., of which Korshak was a 12 1/2 percent owner with Beldon Katleman, owner of Las Vegas' El Rancho Vegas Casino.25 Affiliated, which had contracts at Dulles Airport outside Washington and the Seattle World's Fair, had been given the contract when O'Malley was threatened with an opening-day strike by the first company he had hired. With Affiliated, O'Malley was able to cut a typical Korshak sweetheart contract, wherein the parking-lot attendants received one third of what the original workers had demanded.

O'Malley explained that he hired Korshak to resolve the strike threat since it was not good business to open a stadium without the proper workers and he thought it was the right thing to do to settle it quickly. O'Malley told Sy Hersh in 1976, "We did what any ordinary businessman would do. [Korshak] had the reputation as having the best experience in this area. He provided us a little insulation . . . As far as we're concerned, he does a good job. And unless he's been convicted of a crime, we're not going to do anything." 26 After Korshak and Katleman were awarded the contract, they celebrated with a quick tour of Europe, according to the FBI.27 (Five years later, when the new baseball players union met with team owners at Chicago's Drake Hotel, O'Malley held a private meeting with his fellow owners, in which he trumpeted a man who could counsel them on how to deal with the upstart players union. With that, O'Malley left the meeting and returned with Korshak, who had been waiting outside. For the next four hours, Korshak advised the owners on how to deal with the union. Korshak went on to become good friends with Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, who lunched with him at the Bistro.)28

Upon his return from Europe, Korshak negotiated a quick deal that would pay huge dividends. According to court documents, Joe Glaser, owner of Associated Booking Company (ABC), then the nation's third-largest theatrical agency, assigned all of the "voting rights, dominion and control" of his majority stock in the concern to Korshak and himself. The agreement meant that Korshak, who through the 1960s had seemed merely to be the agency's legal counsel, would assume complete control over the company upon Mr. Glaser's death.29

Since the thirties and forties, ABC had specialized in representing important black musicians such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. Under Korshak's regime, ABC would add Creedence Clearwater Revival and Barbra Streisand to its talent roster. Freddie Bell was one of the longest-running ABC acts, coming to Vegas from Philly in 1954. Bell carved out a legendary career with his lounge band, The Bellboys, opening for Don Rickles for ten years, and writing the revised lyrics to the song "Hound Dog," which Elvis Presley heard in Vegas and used for his hit recording.

"I was the token white guy with ABC, with them for nineteen years," Bell recently recalled. "When Joe died in 1969,1 left." Bell has distinct memories of both Korshak and Glaser: "Sid and Joe were very close—they built the La Concha Motel next to the Riviera. But I thought Sid was the power behind the throne, mostly involved in the money end. Joe was a loud-talking tough guy from Chicago, and Sid was just the opposite. It's hard to talk about Sidney because he was so quiet. Nobody really knew the man."30

Korshak's association with ABC was also advantageous for his Chicago mob patrons, who used it to acquire talent, not only for their Vegas holdings, but also for events on their home turf. In the late fall of 1962, when Sam Giancana held a monthlong gambling party—actually a skim operation—at his suburban Villa Venice Restaurant, he called on Korshak to supply some of the talent. Giancana asked Korshak to pressure Moe Dalitz at the Desert Inn to release Debbie Reynold's husband, singer Eddie Fisher, to him for the stint. As usual, Korshak's intercession with Dalitz was successful, and Fisher joined Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., and Jimmy Durante for the November-December gig.31 However, as seen with the Dinah Shore faux pas, Curly Humphreys, as heard by the eavesdropping feds, once again called Korshak to put him in his place.

"Anything you want to do for yourself, Sidney, is okay," Humphreys dictated, "but we made you and we want you to take care of us first. When Chicago calls, we come first." (The FBI noted that Korshak attended Reynolds's opening at the mob's Riviera in January 1963.) Years later, boss Accardo told Vegas functionary Tony Spilotro, "Korshak sometimes forgets who he works for, who brought him up."32

Sidney Korshak — Double Agent

What Humphreys and Accardo may have suspected, but could not know for sure, was that Korshak was playing a most dangerous game in his efforts to assure his own legal immunity. According to a recently released FBI document, it is now clear that Korshak had been having secret meetings with Clark County (Las Vegas) sheriff Ralph Lamb, to whom he was feeding a measured dose of intelligence on his Chicago bosses, with the knowledge that Lamb would, in turn, act as conduit to the FBI. A 1962 Las Vegas FBI Field Office memo stated, "[Sheriff Lamb] furnished the following information which should not be disseminated outside the Bureau nor should any indication be given to anyone outside the Bureau that Sidney Korshak has been talking to Sheriff Lamb, inasmuch as he furnished the information on a very confidential basis." In one report, describing a Lamb-Korshak conversation at the Riviera on July 22, 1962, Korshak advised Lamb that a recent letter regarding Sam Giancana's movements in Las Vegas, which Lamb's office had sent to the Chicago Police Department, had made its way immediately into the hands of Giancana—Korshak knew because Giancana had showed it to him. Korshak warned Lamb not to trust the Chicago PD. Korshak also tipped to Lamb that Moe Dalitz was building a home in Acapulco, Mexico. The memo went on to say:

Korshak was interested in the overall gambling situation as it pertains to Nevada and would like to prevent any individuals of hoodlum status from gaining a foothold in Las Vegas, and would probably like to see those already established be forced to leave Nevada.

Lamb stated that at no time in his contacts with Korshak has Korshak endeavored to obtain any favors from him or obtain any information regarding Sheriff's Office activities from him. Sheriff Lamb was also of the impression that Korshak possibly furnished him this information so that it could be furnished to the FBI, since on his last contact with Korshak, Korshak had inquired of Lamb as to his association with the FBI in Las Vegas. Sheriff Lamb told Korshak on that occasion that he worked closely with the FBI and that the FBI could have any information in possession of the Sheriff 's office, or any assistance whatsoever. Korshak again told Lamb that he felt that the cooperation between the Sheriff's Office and the FBI was the way law enforcement should be handled . . . Korshak classified [DELETED] as a "punk" and told Lamb that he should not tolerate any type of interference from ["Peanuts"] Danolfo or anyone connected with the Strip hotels.33

Apparently, the Lamb-Korshak relationship continued for years. Five years later, when Lamb barred Rosselli from Vegas for all but one day per month, Korshak told a friend that he could "square it with Lamb," but chose not to bother.34 In actuality, Rosselli was himself becoming increasingly skeptical of Sidney Korshak's true loyalties.

The Korshak-Lamb connection was not the only evidence of a Korshak relationship with the Bureau. Eli Schulman, owner of Eli's Steakhouse, one of Korshak's favorite Chicago eateries, once told a mutual friend that Korshak had secretly ratted out L.A. mobster Mickey Cohen, who had also been friends with Guzik in Chicago and Dalitz in Cleveland, to the FBI in 1951.35 "Mickey was becoming an all-around pain in the ass, setting up crap games [in L.A.] just to rob the players," said a Schulman friend, who asked not to be named. Cohen spent the next four years at the federal prison on McNeil Island.*

The Italians think of Korshak as a sort of god and expect him to work miracles, and someday when he fails them, there is going to be a real problem.

FBI INFORMANT36

According to an FBI informant planted inside the Outfit, Korshak's private dance with the feds was not the only action that threatened his relationship with the Outfit. In a telephone interview, the source told his FBI contact that Korshak "set up a racetrack and Korshak took $250,000 that was not his and was caught. As a result of this, a contract to kill Korshak went out, but Korshak was able to stop it and consequently paid back the money. Because of this Korshak always carries a gun and it would appear that he is somewhat apprehensive of the Chicago hoodlums."37 Still another informant added, "Sidney Korshak has turned out to be a rat and has broken away from LCN (La Cosa Nostra) influence."38

Korshak's closeness to Accardo may likely have been his salvation, but even Accardo, who was known to bludgeon victims to death with baseball bats, had finite patience when it came to traitors. All things considered, the foregoing Korshak covert activities may better explain the intense security at Korshak's Bel-Air manse.

At the time of the Walter O'Malley affair, the senior staff of the Los Angeles Times was finally becoming interested in Sid Korshak and the influx of curious Midwesterners to their city. In the early sixties, the Times boasted a tough-as-nails investigative unit housed in the paper's city desk and run by managing editor and ex-marine Frank McCulloch, who had recently come to the paper from his post as Time magazine's L.A. Bureau chief. McCulloch, one of the greatest journalists of the twentieth century, was often referred to as "a journalist's journalist," and author David Halberstam called him "a legend."39

Until this time, the paper's philosophy had been dictated by its founder, Norman Chandler, with an assist from his wife, Buff. "It was an instrument of the Republican Party, and an acknowledged one," McCulloch said recently. "The City Hall reporter at that time was a Republican lobbyist. That's how bad it was. Norman and Buffy paid very little attention to the newspaper as a totality. Norman published it, but he saw it as a business enterprise." 40 It was also well-known that Chandler had reached a beneficial arrangement with labor fixer Sidney Korshak. Journalist and three-time Pulitzer Prize winner Knut Royce, who would later investigate both Korshak and the Pritzkers, recently said of the Chandler-Korshak connection, "Sid kept unions out of the L.A. Times for Norman Chandler."41

However, after the Chandlers' son Otis took over, he made a bold move toward serious journalism, hiring McCulloch to forge a team of serious reporters. Unquestionably, the unit's crack reporters were Gene Blake and Jack Tobin. In 1961, Blake had written a searing five-part expose of the red-baiting John Birch Society. The controversial series cost the paper advertisers and over fifteen thousand subscribers. Tobin, another ex-marine, had earned his stripes as the country's leading investigative sports journalist. "Tobin and Blake were a great team," McCulloch remembered. "Jack was a sports reporter first. I used to use him as a stringer when I was at Time-Life. He was very quiet. The best records man I've ever known. I became real impressed with him." Ed Guthman, former investigative reporter, press secretary to Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and later national editor of the Los Angeles Times, has a similar opinion of Tobin. "Jack Tobin was a great investigative reporter—great with records," said Guthman. "The police and the FBI used to go to him for help."42

McCulloch recently spoke of his team's coverage of the Supermob: "After we covered the strike at Dodger Stadium, Korshak wanted to sue me. One of the movie people called me—I think it was Lew Wasserman—and said, 'What are you doing this to old Sid for?' He said, 'I'm telling you as a friend, Frank. I wouldn't pursue this any further. There could be legal ramifications and more.' I'll never forget that part." (This would not be the first time that Korshak's corporate friends would try to derail bad publicity for Sidney.)

Then the newsman devised a brilliant tactic to deal with the Fixer, as Korshak was now referred to. "It was suggested that we subpoena one of the bosses in Chicago, and Korshak would lose interest in going to court rather rapidly," McCulloch remembered. "And we did serve one of them; I think it was Giancana. We preempted Korshak and we never heard from him again. That's when he donated money to Dorothy Chandler, the publisher's wife."43

McCulloch was referring to a typical Korshak damage-control gambit, aimed at defusing any local coverage of his activities. In 1961, Dorothy Buffum "Buff" Chandler, of the Chandler family that owned the Times-Mirror newspapers, had become the company's vice president for corporate and community relations. In that position, she waged a tenacious battle to realize a dream: the construction of a world-class music center. Envisioned as a privately fostered, but not-for-profit, partnership with the County of Los Angeles, the center site was donated by the county, which raised an additional $14 million using mortgage revenue bonds. Los Angeles rabbi Ed Feinstein remembered Chandler's quest: "She had a problem in 1962. It was her great dream to see a cultural center constructed downtown, giving Los Angeles a cultural gravity it had never possessed. She wanted something much more important. She wanted to bring the city together."44

More concerned with filling coffers than with the source of the donations, Buff courted political opponents such as Paul Ziffren and Sid Korshak. Publisher Otis Chandler, Buff's son, recently admitted, "My mother would court the devil for contributions. Anybody who'd give her some dough."45 Chandler told the understandably press-shy Korshak that his name would never appear in the Times if he would cough up a contribution. Korshak quickly obliged and sent a $50,000 check to Buff's building fund; he likely considered the donation to be a business investment, and a continuation of a relationship he had fostered for years. Back in 1958, Korshak was observed meeting with the Times managing editor L. D. Hotchkiss. Allegedly they were discussing the political future of Congressman Richard Rogers of California.46 However, Hotchkiss was infamous for his refusal to run stories that reflected poorly on the city to the extent of killing important stories about organized crime.47 Korshak's friendship with Hotchkiss had guaranteed his continued anonymity during that previous regime.

The Korshak-Buff Chandler arrangement did not, however, proceed as smoothly as the previous one with Hotchkiss. According to the FBI, although Affiliated was granted the parking concession at the pavilion, Korshak's check was returned because of what Chandler's own reporters were turning up about Korshak's bedfellows.

By 1962, McCulloch had become curious about the aberrant real estate transactions that were a fundamental part of California's recent history. In the spring of 1962, McCulloch pulled aside Jack Tobin and pointed out the window. "One day, almost as a joke, I asked him, 'Who the hell owns the Santa Monica Mountains?' " recalled McCulloch. "He took me literally and went and found the Teamster connection." The more they mulled it over, McCulloch and Tobin began to realize that this prime Los Angeles real estate tract, as yet undeveloped, was an invitation to the kind of corruption that the state seemed to cultivate.48

Tobin and Blake treaded the same path blazed by Robert Goe, Lester Velie, and Art White (albeit with just one specific locale in mind) straight to the Los Angeles County Recorder's Office. After painstaking research, the duo concluded that the Chicago real estate investments in California were ongoing. As noted in their first article on the subject, Tobin and Blake quickly learned that the Chicago-based Teamsters Pension Fund had loaned over $30 million to out-of-state businessmen like Chicago's Pritzkers, Detroit's Ben Weingart, and Texas's Clint Murchison. Hoffa admitted to the reporters that the fund had earmarked some $4 million for the Pritzkers and their Hyatt enterprise, and that he had personally approved the $6.7 million Murchison loan to develop Trousdale Estates, an exclusive gated community at the top of Beverly Hills that housed Korshak's close friend Dinah Shore, Hillcrest regular Groucho Marx, and later, Elvis Presley.

Another Trousdale purchaser was Richard Nixon, who paid $35,000 for his lot at 410 Martin Lane, far below the listed price of $104,250 ($750,000 in 2004 dollars).49 The favor was not surprising, given Nixon's cozy relationship with the Teamsters. In the 1960 election, the Teamsters not only endorsed Nixon, but Hoffa also personally coordinated a $1 million contribution to the Nixon campaign from the Teamsters and various mob bosses including Louisiana's Carlos Marcello.50 As Tom Zander, retired Chicago crime investigator for the Department of Labor, recently said, "Anybody who wanted to pay for it had a connection to Nixon. The locals gave massive amounts of untraced money to Nixon. They got away with murder."51 Interestingly, it now appears that Nixon hid much of his lucre in the same offshore bank haven, Castle Bank, favored by Moe Dalitz, Abe Pritzker, and the architects of the Las Vegas casino skim.52

The loan to Weingart, who had bought so much confiscated Japanese property from Bazelon's OAP, was for a $1.1 million influx into a laundry company he shared with Midwestern trucking magnate James (Jake) Gottlieb, who also owned Las Vegas' Dunes Hotel, itself the recipient of a $4 million Teamsters Pension Fund loan.53

Other red-flag names that began showing up in the transactions included Moe Dalitz and "consultant" Sidney Korshak, who controlled labor at Santa Anita Race Track, another site that was determined to have received a large fund loan. Thus, like so many had done before, McCulloch, Tobin, and Blake began corresponding with Virgil Peterson for background info on the loan-happy Midwestern transplants, especially Korshak, the Pritzkers, Gottlieb, and Stanford Clinton. Simultaneously, L.A. chief of police William Parker asked Peterson for the Korshak file.54

Coincidentally, while the Times' research was ongoing, publisher Otis Chandler threw a cocktail party attended by none other than Robert Kennedy, who nearly spit out his drink when he was informed of the latest finds by Tobin. "He got red-faced and violent," Frank McCulloch recalled. "His voice rose. He said, 'You'd better lay off that!'" The following day, when Ed Guthman explained to McCulloch that Kennedy had already impaneled a federal grand jury to investigate Hoffa, McCulloch grasped the national implications of the California real estate rat's nest they were exposing. McCulloch's immediate superior, Frank Haven, tried to warn him off the story, saying, "Once you get to the point where you can get a guy to talk, then either you or he or both are going to end up in a lime pit somewhere." 55 McCulloch explained that the initial reason for the nervousness was another potential revenue loss like the paper had experienced after the Birch series. Editor Nick Williams also attempted to halt the Teamster series. "Poor Nick Williams was put in the middle," said McCulloch. "He told me, 'Oh, let's drop this stuff, Frank. It's dull; nobody reads it.' I told him he'd have to order me."

Instead of backing off, McCulloch ordered Tobin and Blake to double their efforts. Of course, any scrutiny of Hoffa's California interests would lead to Sid Korshak, which in turn would inevitably track to Ziffren, Bazelon, Arvey, Hart, and the entire seamy underbelly of the Los Angeles economy. For a year, the series continued, inching inexorably toward the Ziffren-Arvey nexus. "There were twenty-seven stories in the series, and the Chandlers were upset all along," said McCulloch. Suddenly, word came from above—as in Otis Chandler—that the series had to be dropped. "Frank, you're killing me. Don't run any more of those pieces," ordered Chandler's underling Williams. McCulloch finally caved. "Nick was getting pressure from above," remembered McCulloch. "So we ended it."

"Obviously some pressure was put on the Times and they buckled," said Ed Guthman. "Tobin left the paper over that issue."56

McCulloch also left the paper soon thereafter. Gene Blake was effectively stopped from going further when he was dispatched to the Times' London bureau, a good fifty-four hundred miles from the L.A. County records files. Tobin went to Sports Illustrated, where he was an award-winning discloser of corruption in sports. Connie Carlson, investigator for the California attorney general, was a friend and colleague of Tobin's, sharing his interest in the Chicago underworld's usurping of the state. Recently, Carlson remembered, "Jack Tobin became very disenchanted with the Times because there was no follow-up on his discoveries. It was disappointing for a number of the reporters at the Times, because under Otis Chandler they had formed a very formidable investigative unit. They were going full bore on everything. And suddenly it all came to a halt."57 Frank McCulloch returned to his former home at Time magazine, where he ran its Saigon office. "I left for a combination of reasons," McCulloch said. "In addition to the problems with the series, Nick wanted me to start a Sunday magazine, and I didn't want to do that—I had left a magazine to come to the paper. Then I got a call from Henry Luce, who said to me, 'Handle that mess in Southeast Asia.' The guy who succeeded me, Frank Haven, hated that corruption stuff. He only wanted to cover City Hall and run wire stories."

Although potential financial woes were the implied reasons for the crackdown, Otis Chandler may have had additional motivations for muzzling his reporters. "It turned out that the paper's holding company, Chandler Securities, owned property that had Teamster money in it," McCulloch said recently. "And they were pretty sure we were going to reach that, which we did, and we ran a story on it."58 Tobin and Blake had also found that Chandler was a large stockholder in Korshak's Santa Anita Race Track, a long-suspected venue for cleaning mob money. But there was more: the reporters' next scheduled story was to focus on another Los Angeles company, Walt's Auto Parks, which had received Teamster money that also appeared to have been laundered for the mob. This sleazy company, which operated parking lots throughout downtown Los Angeles, counted none other than Otis Chandler as one of its heaviest investors.59

Although Chandler declined Korshak's check, others continued to feast at his trough; in November 1962, Korshak underwrote dinner costs for group attending a charity event benefiting the Cardinal Stritch School of Medicine at Loyola University, where both Korshak brothers were trustees. Sid's brother Marshall was host for the bash.60 Two years later, on November 24, 1964, Sidney, who had himself received an honorary doctorate from Loyola, again showed his support for the Stritch School, this time underwriting the entire cost ($50,000) for the first annual Sword of Loyola Awards Dinner and Benefit. With comedians Allen & Rossi and the Chicago Symphony performing at the Hilton Hotel venue, the dinner raised over $250,000. The Sword prize paid tribute to people who "exhibit a high degree of courage, dedication, and service." Seated at the head table with Sidney was the prize's first recipient, J. Edgar Hoover.61

Like Marshall, Sidney gave extensively to numerous Jewish causes. Friend Leo Geffner recently observed, "Sidney was a very strong supporter of Israel—he contributed a lot of money. Sidney never hid his Jewishness, never tried to assimilate."62 The largesse was not only emblematic of the Korshaks' lifelong charitable works, but also of the brothers' great love and respect for each other. "Marshall and Sidney were so close it was unbelievable," said one friend of both, who asked that his name not be used. "They were on the phone with each other four or five times a day. And they were so proud of each other. Marshall was proud of Sidney because of his accomplishments and the connections that he had. And Sidney was proud of Marshall because of his public life—he was straight as an arrow. He was the only major Chicago politician who didn't have his hand in the till."63

Eventually, the opening of the Music Center for the Performing Arts went off without a hitch on December 6, 1964, becoming the home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and fountainhead for all of Southern California's performing arts.* Lew Wasserman was enlisted by Dorothy to be president of the Center Theatre Group, which supported the Center's drama program; Wasserman, in turn, brought in Paul Ziffren as counsel to the group. In her nine-year campaign, Buff raised $20 million in private donations, earning her the prestigious cover of Time magazine.

Vegas II

Korshak is acting as a front man to work out a deal in Las Vegas for Chicago hoodlums to invest in Las Vegas gambling casinos.

JANUARY 16, 1961, FBI TELETYPE64

In February of 1962, the FBI noted that Sam Giancana was making rumblings about expanding the gang's share of the Nevada nest egg. Giancana functionary "Lou Brady" (Louis P. Coticchia) was utilizing Sidney Korshak to arrange financing of an $11 million casino-hotel in Reno. On wiretaps, Giancana was heard suggesting, "Korshak would expend his best efforts should he be made a partner in this deal and given five or ten points [interest]." 65 The FBI summarized that Johnny Rosselli was heard talking to Giancana to the effect: "Negotiations are in progress in Las Vegas for the Chicago organization to obtain a tighter grip on Las Vegas hotels and casinos, and negotiations are being made through Sidney Korshak."66 Simultaneously, Giancana wanted to make a grab for Jake Factor's interest in Las Vegas' Stardust, and whether "Mooney" knew it or not, he could not have chosen a better time to plan a hostile takeover.

By the summer of 1962, Jake Factor was in full image-remake, if not life-remake, mode. His epiphany was understandable given two recent events that had to have shaken him to his core: the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was unrelenting in its threat to deport him back to England, where he would likely have spent the rest of his life in prison, and the Chicago Outfit had threatened to end his life immediately if he didn't sell the Stardust back to their consortium with Moe Dalitz. After months of negotiations coordinated by Sid Korshak, Factor sold his interest in the Stardust to Moe Dalitz's Desert Inn Group, which was in fact a partnership of the Chicago and Cleveland crime syndicates. When the deal was finalized in August, the $14 million price tag prompted both the U.S. Department of Justice and the Nevada State Gaming Commission to investigate the hotel's true ownership.

By this time, Bobby Kennedy had authorized the planting of illegal bugs (microphones) in seven of the Strip's hotels, including Moe Dalitz's Desert Inn executive suite. Six months after Factor had unloaded the Stardust, the feds eavesdropped while Korshak and Dalitz discussed the various sales Korshak had brokered in the past, and the Factor sale in particular.

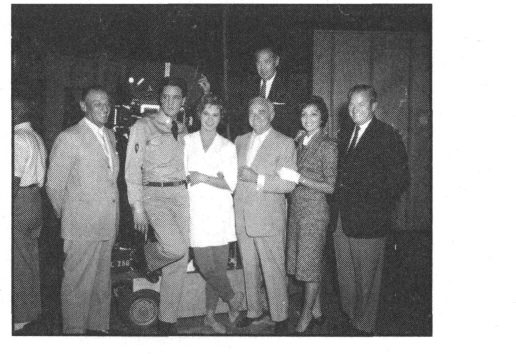

In 1960, GI Blues costars Elvis Presley and Juliet Prowse visit with the Desert Inn's Moe Dalitz and Wilbur Clark. (Left to right) Dalitz, Presley, Prowse, Wilbur and Toni Clark, Cecil Simmons, and Joe Franks behind Clark (Wilbur Clark Collection, UNLV Special Collections)

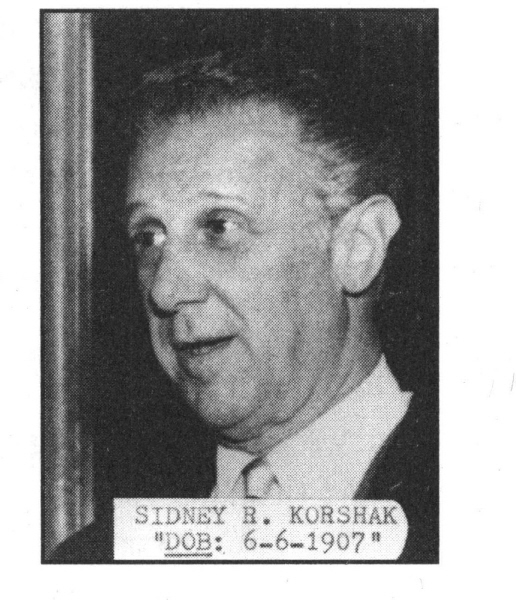

Dalitz in Vegas, undated (Cleveland State University, Special Collections)

"I scared the shit out of him [Factor] from day one about what was going to happen," Korshak boasted to Dalitz. "I think that was the one reason he finally agreed to give us the option to purchase."

Korshak emphasized the point by telling how, when Curly Humphreys had recently instructed Korshak to send Factor back to Chicago for a meeting, Factor became unstrung.

"He said, 'Well, I've got to run now, but I'll talk to you in about a half hour,' and that was the last I saw of him. He caught the afternoon plane," Korshak informed Dalitz. At this point both Dalitz and Korshak burst into laughter, with Korshak adding, "So this is consistent with what I was saying—he is frightened to death and that is how we were able to make this fucking deal." The Bureau also knew that Korshak had taken Rosselli to meet with Factor at the Beverly Hills Friars Club for a conference, wherein "Factor looked worried."67

The discussion then turned to Bobby Kennedy's war on the underworld, ironic since Bobby would soon be listening to the tape of this conversation.

"Bobby has been trying for six months to catch someone either in Las Vegas or Los Angeles who is carrying money," said Korshak. To fight this onslaught, he advised, all concerned should plead the Fifth Amendment when questioned under oath. As one of Korshak's closest Hollywood friends, Bob Evans, summarized, "Sidney's first commandment was, the greatest insurance policy for continued breathing is continued silence."

"Moe, I have preached this all over the country," Korshak counseled Dalitz. "Do not answer anything. I have testified before grand juries in New York and Chicago, and at that time I could do it because then I was dealing with certain people. I tell you now, Moe, if I am called before any grand jury, I will take the Fifth Amendment, and I am a lawyer. I will give my name and address, and from that point on I will answer no questions. They can disbar me, but I will take the Fifth. Now 1 have to take the Fifth because I am operating in a different atmosphere."68 (Author's italics.)

The wise counsel was no surprise to one of Korshak's oldest friends in the Chicago legal fraternity. The lawyer, who asked not to be named, had also met Dalitz, who shared a personal story with him. "During the war, it was Sidney, who I had not met at that point, who recommended me for OCS," Dalitz had said. "I'll never forget it." The source added, "As a result, Dalitz didn't go to the bathroom without checking with Sidney"69

The conversation was also revealing on another front, as Korshak related how close he had become to Sam Giancana, and how the two had dined together recently. Korshak then told Dalitz to let him know if there was any message he wanted delivered to the Chicago boss.

Korshak in Vegas (FBI)

As for Factor's INS problem, apparently the character references by Al Hart and the others had failed to impress the feds. Thus, Factor decided to go over their heads, this time with the legal assistance of Abe Pritzker's partner Stanford Clinton. Somehow, Factor was able to persuade Attorney General Bobby Kennedy to bring him to Washington to discuss the INS case.

Factor later told the press that during their chat, Bobby Kennedy slyly brought up the fact that he needed donations to help secure the release of 1,113 Cuban Brigade soldiers captured by Castro's forces after the disastrous April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. Reports had been circulating for months that Kennedy was placing threatening calls to business leaders with tax or other pending legal matters, practically extorting the funds from them. In conversations monitored by the FBI, it was clear that even the underworld was impressed by Bobby Kennedy's mastering of the "velvet hammer" extortion approach. On one occasion, the agents reported that Giancana aide Chuckie English "pointed out that the attorney general raising money for the Cuba invaders makes Chicago's syndicate look like amateurs."

After a number of meetings with "the Barber" in December 1962, Bobby Kennedy recommended to his brother that Factor be pardoned—this despite what his own wiretaps were telling him about Factor's continuing relationship with the mob at the Stardust. Bobby's decision became clearer when Factor told reporters that he'd contributed $25,000 to Kennedy's "Tractors for Cuba" fund.*

President Kennedy granted Jake's pardon on Christmas Eve, 1962, the same night the prisoners landed in Miami, and just one week after the INS announced its decision to deport Factor.70 But soon after, Bobby began to have misgivings about what he had done. Jack Clarke, who worked in the investigative police unit of Chicago's Mayor Daley, recently recalled what happened next. "Bobby Kennedy called me and asked if there would be any problem if Jake Factor were pardoned," said Clarke. "When I explained the details of Factor's Outfit background—Capone, Humphreys, the Sands, et cetera—Bobby went, 'Holy shit!' He then explained that he had already approved the pardon." Clarke added that Bobby's dealings with the Factor case were not atypical: "RFK didn't know what he was doing in the Justice Department. He had no idea of the subtleties, the histories of these people." Clarke, however, was unaware of Factor's little donation.

Eventually settling in Los Angeles, the much traveled Factor took particular interest in the welfare of underprivileged black youth in the Los Angeles district known as Watts. In the 1960s, after bestowing a $1 million endowment (allegedly through the Joseph P. Kennedy Foundation) on a Watts youth center, a Los Angeles Times reporter brought up his ties with the Outfit. Factor broke into tears, asking, "How much does a man have to do to bury his past?"

Jake Factor was not the only Supermob associate having travails during 1962. Lew Wasserman and Jules Stein saw the unrelenting antitrust nuisance reach the breaking point that year. For decades the Department of Justice had hinted at a crackdown on the runaway MCA juggernaut. Until now, authorities had failed to rein in the company whose books were such a closely guarded secret that even Wall Street was unable to assign a credit rating. Now, thanks to a persistent DOJ prosecutor named Leonard Posner, it looked as if something was actually going to happen.

Throughout the winter of 1962, a grand jury took testimony from actors, producers, and clients who had any dealings with what was now referred to as The Octopus. During the proceedings, MCA, with Paul Ziffren acting in the capacity of MCA "house counsel," intimidated actors such as Joseph Cotten and Betty Grable from testifying and obtained leaks from the testimony of those who did.71 Those who dared to testify, such as Eddie Fisher, Paul Newman, Audrey Hepburn, and Carroll Baker, gave measured responses that betrayed their fears over losing work if they offended the Octopus.

By far the most anticipated testimony was that of the man who'd granted the blanket waiver to MCA, former SAG president Ronald Reagan. On February 5, 1962, Reagan appeared before the grand jury, but his testimony wasn't unsealed until 1984, in response to a Freedom of Information Act request by David Robb, then a reporter for Daily Variety (later the chief labor and legal correspondent for the Hollywood Reporter).

Reagan's appearance was most notable for his staggeringly—some might say impossibly—bad memory. Most shocking, he claimed no memory of the MCA blanket waiver, arguably one of the most important SAG decisions in its history. The befuddled federal antitrust division attorney who conducted the questioning, John Fricano, attempted in vain to refresh him.

"This was a very important matter which Screen Actors Guild was taking up and it was the most important point of the guild," Fricano reminded the actor. The nonplussed Reagan asked when the action was taken. Fricano replied, "July 1952."

"Well, maybe the fact that I married in March of 1952 and went on a honeymoon had something to do with my being a little bit hazy," answered Reagan.

"Do you recall whether or not you participated in the negotiations held by MCA and SAG with respect to the blanket waiver in July of 1952?" asked Fricano.

"No, I think I have already told you I don't recall that. I don't recall," insisted the future U.S. president.

Fricano then attempted to plumb the details of the 1954 waiver extension, with the same lack of success.

"I don't honestly recall," Reagan answered. "You know something? You keep saying [1954] in the summer. I think maybe one of the reasons I don't recall was because I feel that in the summer [of 1954] I was up in Glacier Park making a cowboy picture."

When Reagan lied in denying he had been a producer while serving as SAG president, the interrogators were so convinced of his perjury that they began impounding his tax returns for 1952-55.

On June 17, 1962, DOJ's lead MCA prosecutor, Leonard Posner, filed a 150-page brief that predicted a criminal indictment against MCA was but a week away. Posner had found an "honest and trustworthy" source who testified that Reagan had granted the MCA waiver in exchange for the job on GE Theater.72 Among the infractions cited by Posner, in furtherance of a continued violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act:

• Monopolization of the trade in name talent.

• Monopolization of the production of filmed TV programs.

• Conspiracy with SAG regarding the blanket waiver and the above monopolies.

• Restraint of trade (including packaging "tie-ins," extortion for services not rendered, blackballing independent producers, discrimination, and predatory practices).

Lew Wasserman then flew to Washington to plea/negotiate with Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who dropped all the criminal indictments despite the illegal blanket-waiver deal and MCA's twenty-five-year history of violating the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. Leonard Posner's case against MCA would never be heard in court. As part of the agreement, MCA vacated its artist agency work in favor of its more lucrative production wing, which immediately scooped up Universal Studios and Decca Records. MCA-Universal quickly became the biggest film producer in the entertainment industry, while the agency business was sold to former MCA employees who formed Artists Agency Group, which continued to deal almost exclusively with MCA.

Two months after he quit his job with DOJ, Posner died of a heart attack. The brilliant lawyer was described as "bitter" by friends and "disappointed" that his superiors didn't pursue the MCA case. If Posner was suspicious of his boss's inaction, he had good reason, for a potential conflict of interest loomed not far in the background: not only had Bobby Kennedy assigned Jules Stein's son-in-law, William vanden Heuvel, as his adviser on the MCA matter, but one of MCA's lead attorneys on the case was Hy Raskin of Chicago, one of the Kennedy family's most trusted advisers during the 1960 campaign.73 Within a year of the agency bust-up, Wasserman established himself as one of the Democratic Party's chief contributors. Ed Weisl Sr., who arranged MCA's purchase of Paramount's library and ran interference for Wasserman during the DOJ investigation, suggested that Wasserman throw a fund-raiser for West Coast high rollers to gather support for John F. Kennedy's 1964 reelection campaign. Wasserman happily agreed to cohost the June 7, 1963, $l,000-a-plate dinner with Sid Korshak's great friend and client Eugene Klein.51' Afterward, aided by United Artists chairman Arthur Krim and Paul Ziffren, Wasserman came up with a gimmick called the President's Club, which gave businessmen increased access to the president in exchange for sustained contributions to his campaign coffers. For a $1,000 contribution, club members received a gold-engraved membership card, invitations to cabinet briefings, and an annual club dinner. But what was most prized was the increased purchase that accompanied such access to JFK.74 Years later, when Richard Nixon became aware of all the Hollywood Jewish money going to the Democrats, he demanded an IRS workup on them. "Can't we investigate some of the cocksuckers?" Nixon can be heard saying on the White House tapes.75

The success of Wasserman's President's Club made the former Justice Department foe a hero to the Kennedy administration. And if Bobby Kennedy's interest in MCA wasn't completely erased by Wasserman's gambit, it would be on November 22, 1963, when his brother was gunned down in Dallas, after which Bobby's interest in all ongoing cases vanished as he retreated into virtual catatonia.

After the MCA breakup, Reagan formally became a Republican (which he had long been in spirit) and entered into a production partnership with MCA. The company soon found him more work as the host of the television series Death Valley Days, while staking him for a career in politics.

As Wasserman exercised his influence on the national stage, Sid Korshak did likewise on the state level. In 1984, the staff of the New Jersey Gaming Commission concluded in a report, "It is quite evident that over the years [Korshak] has made good contacts with very powerful politicians . . . Korshak's list of past and present associates reads like a Who's Who of prominent southern Californians." By the early sixties, Korshak's business style was well-known for its unconventionally—million-dollar deals were cut in swank restaurants, hotels, or in Korshak's mansion. The same modus applied to his political machinations. At one of his famous home business brunches in 1962, Korshak mediated internal Democratic Party squabbles between Paul Ziffren and Eugene Wyman, Ziffren's successor as California Democratic National Committeeman. The difficulties included differing strategies employed in the Brown-Nixon gubernatorial contest by Jesse "Big Daddy" Unruh, Speaker of the California Assembly, who had been accused of hiring ten thousand precinct workers to elect Pat Brown over Richard Nixon.76 Even Brown was upset with Unruh, telling his aide at one point, "Do you know that Unruh is the German word for unrest? It's where the English word for unruly comes from. Appropriate, isn't it?"77

With Ziffren, Wyman, and Unruh now breaking bread at Sidney's Chalon breakfast nook, the Fixer worked his usual magic. "Over coffee, Sidney finally said to Paul, 'You know, we Democrats have a hard time in the s t a t e , ' " one source told the New York Times. " 'We shouldn't be taking each other on in public. If you've got a complaint, you should go and talk to Jesse. If you can't get satisfaction, you come to me or Gene before spouting off to the press.'" The confidential source noted, "There was no threat, nothing but sweetness. But, my God, from that day on Paul Ziffren never said another unkind thing about Jesse Unruh." Indeed, Ziffren agreed with Korshak's wisdom, later saying, "It was more important to elect Pat Brown than to have fights."78

The resultant truce was pivotal in that year's gubernatorial election victory (by 297,000 votes out of 6 million cast) of Pat Brown over Richard Nixon, who had stooped to new lows in election fraud and red-baiting in his attempt to defeat Brown. During the campaign, Nixon's team (which included many who would later execute the Watergate break-in) formed the phony Committee for the Preservation of the Democratic Party in California, which mailed nine hundred thousand postcards attacking the "left-wing minority" who had hijacked the party and the California Democratic Council (CDC). By this time, the Brown-Ziffren alliance had been resuscitated after Brown appointed Ziffren to head up the CDC. Nixon's ploy was just an updated version of the Knowland charges that had failed in 1958. Nixon also ordered the doctoring of photos in such a way as to depict Brown consorting with known Communist leaders. The Democrats sued, and after protracted hearings, the case was settled in 1964 for a reported $500,000. During the litigation it was determined that Nixon was personally involved in the shenanigans.79 Writing for the Nation, Carey McWilliams summed up Nixon's ethos, saying, "As in 1952, the faceless, amoral Nixon is still on the make, still fighting Communism, still full of tricks, haunted by, as always, the lack of self-knowledge."80

The new year 1963 saw Sid Korshak maintaining the same hectic pace he had the previous year. His FBI file noted that he attended Debbie Reynolds's Vegas opening at the Riviera in January. Sid's wife, Bee, continued her globe-trotting; in April, she journeyed to Madrid with her two sons and actress Cyd Charisse, wife of Sid's old Chicago pal Tony Martin. When they returned, the Korshaks hosted Tony and Cyd at the Riviera in Vegas on the occasion of the Martins' fifteenth wedding anniversary. The Kirk Douglases and Vincente Minnellis also attended.81 Gus Alex's wife, Marianne, continued her close friendship with Bee, while Sidney remained pals with Gus. When Marianne sought to divorce Alex, whose way of life proved too much for her, the Korshaks counseled them. When the love-struck Gussie initially balked at the separation, Sidney convinced him to grant Marianne the divorce. Alex licked his wounds at Korshak's beachfront Malibu rental, availing himself of Sid's Cadillac while there.82 Bee Korshak eventually brought Marianne out to L.A., where she helped her get a job as Dinah Shore's fashion adviser on her nationwide television show. Marianne Ryan Alex eventually married Shore's producer, Fred Tatasciore.

On April 15, Korshak was spotted trying to enter Al Hart's Del Mar Racetrack with Johnny Rosselli, but they were turned away because Rosselli was barred from the premises.83 During that same week, an old flame of Johnny's, Judy Campbell, contacted Sid on the advice of Sam Giancana. At the time, Campbell was sleeping with both President Kennedy and Giancana and was under constant FBI surveillance, or, in her opinion, harassment. A number of grand juries were impaneled to look into both Giancana and Rosselli, and Campbell feared testifying before them. Sam told her that Korshak "should be able to take care of things for you. Any more problems, just give me a call."84 Korshak asked her to fly to Vegas, where he was obviously busy with the Martin festivities. In her autobiography, My Story, Campbell described Korshak: "Sid is tall, with a long face, large soft nose, and small eyes. Everything about him is deliberate, relentless . . . No hurry. It can always be done—that kind of attitude. No one was going to stop him. No one was going to say anything unpleasant. No one was going to change his mind . . . I was never afraid of Sam, but Sid frightened me. I could feel the power he wielded as he sat there watching me . . . I had as much chance of staring him down as I would have had with a lizard."85

Back in Beverly Hills on the nineteenth, the two met again at the Riviera's second-floor reservation office on Wilshire, and later that day at Korshak's evening hangout, the Polo Lounge in the Beverly Hills Hotel. At the meetings, Korshak assured Campbell she would not have to testify. In the coming weeks, Campbell was stunned by her good fortune. "Someone worked a miracle," she wrote. "I didn't have to appear before the Grand Jury."

There are also anecdotal reports of Korshak's intervention with another JFK paramour, actress Marilyn Monroe. Although the details of the contact are unknown, a number of Hollywood insiders heard the rumors. Milt Ebbins, Peter Lawford's longtime manager, was among those who recently spoke of it. "I had heard that Marilyn went to Sidney for some representation," Ebbins recalled, "but for what exactly I never knew."86 There are numerous ways Korshak could have been drawn into the Monroe maelstrom. In addition to being friends with Monroe's confidant (and Kennedy in-law) Peter Lawford, Korshak was close with Giancana and Rosselli, who were well-known friends of Monroe's,87 Giancana having partied with her and Sinatra at the mob hangout Cal-Neva Lodge just one week before her fatal overdose on August 4, 1962.88 (Over the years, Sinatra, Joe Kennedy, and Sam Giancana had owned a piece of the hotel-casino, which straddled the California-Nevada border on the north shore of Lake Tahoe.)89

Monroe's and Campbell's boyfriend President Kennedy was meanwhile beginning to attend Democratic Party fund-raisers in anticipation of the next year's presidential race. On June 7, 1963, Kennedy had a fund-raiser in Los Angeles, which was attended by Korshak associates Al Hart and Eugene Wyman; Korshak clients in attendance included Donna Reed and Dean Martin.90

All the while, Korshak's comings and goings were being watched, not only by the likes of Jack Tobin and Robert Goe, but also by the FBI. Los Angeles FBI agent Mike Wacks was one of those monitoring the elusive power broker. "Sidney was one of our primary targets here in L.A. because we felt that he controlled a lot of the local Teamster business," Wacks recalled. "He had a great say and gave an awful lot of advice to the Chicago mob on how to run the Teamster pension funds. We knew this from a lot of different sources. Over the years, we followed Sidney because our boss was really interested in getting him. He would put us on him for a day or two just to see what he was up to. He knew he was being followed but he didn't care. He just didn't care. He just said, 'Hey, these are my clients and that's what I do.'

He was like Teflon, he could never get charged. He was amazing. He was one sharp cookie. Nobody ever ratted him out, and he never got caught on a wire. It's just amazing."

* Ocean's Eleven, in addition to boasting JFK's visits to the set, provided a sneak peak into the world of the Supermob—for those who knew what to look for. The casino portions of the film were shot largely in Korshak's Riviera, and Korshak saw to it that his great friend George Raft was given a role in the movie as a casino owner; the opening scenes took place in Drucker's, the Beverly Hills barbershop preferred by Korshak, Rosselli, Siegel, Raft, et al.; Frank Sinatra's character "Danny Ocean" was married to "Bee," played by Angie Dickinson; the five casinos robbed by Sinatra's gang were the five most closely rumored to have been run by "the boys"—the Flamingo, the Sands, the Desert Inn, the Riviera, and the Sahara. But, for the knowledgeable, the most memorable moment in the movie came when actor Akim Tamiroff, referring to the gang's enlistment of an ex-con in their scheme, uttered one of the most absurd examples of high sarcasm ever memorialized on celluloid: "A man with a record can't get near Las Vegas, much less the casinos."

*When Judge John Barnes finally reviewed the case, he concluded, "The kidnapping never took place." The parole board agreed.

*In the late forties, Factor served six years in prison for mail fraud involving the sale of other people's whiskey receipts in the Midwest, but he never stood trial for the thousands he bilked in the United Kingdom, not to mention the railroading of Touhy.

*In 1935 Berger had been indicted with another Capone hood for attempting to fence $235,000 in bonds stolen from a mail truck. In 1952, when Berger's office was raided, Accardo strongarm Paul "Needle Nose" Labriola, a friend of Sidney Korshak's, was arrested there with Abe Teitelbaum, then advising Accardo. Labriola's garroted body was found in a car trunk in 1954. Berger later fronted for the Outfit by running the Latin Quarter nightclub, where he was charged with bilking customers out of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

*A 1958 FBI report discloses that Korshak's unlisted phone number (Rand 6-2038) was in Mickey Cohen's address book.

*The complex, completed in 1967, includes the 3,197-seat Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, which hosted the Academy Awards for the next four decades, the 750-seat Mark Taper Forum, and the Ahmanson Theatre, which offers flexible seating for 1,600 to 2,007.

*It was reported that Factor's payoff to RFK was an Outfit practical joke: the money came from the skim the gang was taking from Las Vegas casinos.

*Klein, the owner of America's first conglomerate, National General Corporation (which owned a theater chain and the San Diego Chargers football team), told author Dan Moldea, "I hired Sidney Korshak for National General as a labor negotiator. He was terrific. He got things done. I paid him a retainer, fifty thousand dollars a year. Whenever we had any labor problems, I picked up the phone and called Sidney. Whatever he did, it was done. He and I were as close as brothers." (Moldea, Interference, 160)