DESPITE THE APPALLING lack of encouragement from Washington, agents from all federal departments continued on their own initiative to watch over Korshak and the Supermob. One such agent was Andrew Furfaro, who, at the time, headed up the Western Division's elite, and undisclosed, Organized Crime Unit of the Internal Revenue Service. "We were IRS, but we weren't," Furfaro clarified recently. "It was a Treasury intelligence unit that blended between the Justice Department and the IRS. We could pull any tax return anywhere in the country. We had subpoena power. We had the ability to start grand juries. We wrote the subpoenas, pocket subpoenas, for the grand juries and served them as well."1 (Furfaro would eventually run the IRS's Operation Snowball, the first major investigation of illegal contributions from corporations to politicians, focusing on thirty-one companies in Los Angeles alone.2 "It was the first political investigation in the country," said Furfaro. "We had every major corporation in the country under investigation. This is the thing that changed laws. They had to change the audit laws.")*

Working under the IRS's Gabe Dennis, Furfaro was told to go to school on the most insidious forms of white-collar corruption, California-style. While the politically vulnerable elected authorities played cat and mouse with local crime gangs, Furfaro's IRS unit knew that these prosecutions represented little more than putting on a show for the voters. Gabe Dennis was prescient enough to deduce that the more insidious corruption practiced by the seemingly immune Supermob dwarfed that of the Mickey Cohens and Jack Dragnas of the world. Thus, Dennis knew exactly how to bring his charges up to speed. "I was sent to live with Jim Hamilton of the LAPD," said Furfaro. "He became my tutor, and we set up crime files on just about everybody." Hamilton, of course, was one of the earliest sentinels to become aware of the Western intrusion of the Supermob through his investigations of Ziffren, Greenberg, and the Hayward Hotel nexus. Furfaro also developed a close working relationship with Connie Carlson, the Supermob watcher in the state Attorney General's Office.

In short time, Furfaro became intrigued with the transplanted Chicagoans who seemed to be the new power brokers in California. He tracked players like Al Hart, Paul Ziffren, Sid Korshak, and even the Western investments of patriarch Jake Arvey. Operating on a shoestring, Dennis, Furfaro, and the rest of their small unit tracked the Supermob up and down the West Coast and into the Nevada casinos.

In 1963, Furfaro's band was in the midst of "following the money" when they became aware of Sidney Korshak. While investigating an L.A. bookie named Benny Ginsburg, Furfaro stumbled onto the "Chicago connection" and Korshak specifically. "I served Ginsburg with a subpoena, but his doctor, Dr. Elliott Korday said he had too bad a heart to appear before the grand jury" Furfaro remembered. While checking out Ginsburg, the team learned that his bets were being "covered" in Las Vegas. "The L.A. bookie layoff bets were handled in Vegas, because the locals couldn't cover it," added Furfaro.

When the trail led them to Vegas, the IRS unit stumbled into the rat's nest of skimming and money laundering that w7as Las Vegas in midcentury. "We learned right away that the Vegas authorities couldn't be trusted, so we covered it out of L.A.," said Furfaro. "Vegas became a 'suburb' of L.A. because the FBI wasn't doing it. We knew that Hoover was with Al Hart in Del Mar, so we just said, 'The hell with the Bureau. We'll cover it.' By 1962, we controlled Vegas writh a team of one hundred and fifty guys from the ATF and IRS," recalled Furfaro. "We sat at every table in every hotel. We did a count. This has never been written about."

The investigation quickly focused on Jake Factor's Stardust and a close friend of Sid Korshak's named Mai Clarke. "The Stardust's bad-ledger book was the way they got the money out. The Stardust was writing off bad debts for guys who never even went there. This was the way to hide the skim by saying they lost it to a gambler who didn't pay off his marker. Technically, a guy supposedly goes to the count room and gets twenty-five grand. They put the marker in the cage, but the guy never comes back and pays off his marker. Mai Clarke was one of the names they used for the fake-debt writeoffs. And he never even went to Vegas. He didn't even know where Vegas was."

The background check of Mai Clarke opened up the proverbial can of worms. Clarke was a Chicago racketeer associated with none other than Korshak's pal Charlie Gioe.3 Early in his career, he was the front owner for Tony Accardo of Gioe's Clark Street bookie joint, where Sid's brother Bernie had also worked.4 He was also an investor in Vegas' Sands Hotel, which had been financed by a consortium that included Al Hart's former partner Joe Fusco.5 Sidney Korshak, in fact, admitted to authorities that he had known Clarke, a fellow part-time inhabitant of Palm Springs (and a frequent guest at Korshak's condo), for twenty-five years, sponsored Clarke into the Beverly Hills Friars Club, and helped his son Malcolm Jr. gain admission to Loyola of Chicago, where the Korshak brothers were trustees. Clarke paid Korshak's brother Bernard $250 a month to run the cigar shop in the front of Clarke's Chicago bookie joint.6

But what drew the investigation into sharper focus was the IRS unit's scrutiny of Clarke's tax filings, which showed that he was receiving a substantial paycheck from a notorious Chicago business for which he performed no discernible service.

"We traced Clarke back to Duncan Parking Meters in Chicago," said Furfaro. "He was getting twenty-five thousand dollars a year from Duncan as their meter representative in Mexico—but there were no parking meters in Mexico!"

The Duncan Parking Meter Company was well-known to Chicago authorities. The firm was ostensibly owned by Jerome Robinson, whom the Chicago Tribune referred to as "somewhat of a mystery." Robinson, locally described as connected to the Chicago Outfit, lived at Chicago's Carlyle, where he was a neighbor of Abe Pritzker's and Henry Crown's brother Irving's. In January 1963, Robinson had been convicted of perjury in a New York grand jury investigation of his supposed bribery in the sale of parking meters to New York City, for which he received a suspended sentence.7 Robinson was well acquainted with the Korshak brothers; Marshall Korshak would obtain tickets for Robinson and his family to attend a 1980 Washington, D.C, reception for Pope John Paul II.

According to an FBI informant, Sidney Korshak had "muscled out" the original ownership of Chicago's Duncan Parking Meter Company, thus allowing his good friend Jerry Robinson to take over. Robinson then bought a house in Beverly Hills, while Korshak's Chicago friends actually ran the company. In an interview with the FBI, Korshak admitted to being the "legal counsel" for Duncan. The FBI report concluded that Duncan "was controlled by the Outfit, specifically Gus Alex . . . and Sidney Korshak." The Bureau was also told that Robinson often visited Korshak in his Palm Springs condo.8

Furfaro concluded that Clarke was being paid by Duncan for the use of his name and likely his address in Palm Springs, from where the money was being funneled to Mexico, and from there to offshore Caribbean banks. "Duncan Parking Meters was the conduit," said Furfaro, "but I don't think the old man [Jerome Robinson] necessarily knew about it."

Sid Korshak's name not only surfaced because of his connection to Clarke and Duncan, but also through his direct linkage to the original Benny Ginsburg investigation in Los Angeles. Furfaro ran the numbers in the gambling sachem's phone records and determined that one number belonged to Korshak. Furfaro described what happened next: "So Clarence Turner and I went to Korshak's home in Bel-Air, and his valet came out and told us not to park in the driveway because the grease was getting on it. When we got into the house, it was not a normal house—it was an office. It had about ten card tables set up all around the house. This was a meetinghouse. Korshak made reference to 'holding labor meetings' at the house. Initially, he was appalled by us; we were a nuisance. 'I've been interrogated by experts,' he said. 'Who do you guys think you are?' "

Eventually, Korshak relaxed and spoke casually with the agents. "He talked about his brother more than himself," remembered Furfaro. The agents served Korshak with the grand jury subpoena, and he dutifully appeared downtown to answer more questions. What follows are highlights of Furfaro and Turner's report of the interview, dated October 23, 1963:

• "The interview was quite cordial and informal, and in most instances Mr. Korshak volunteered information without being asked."

• Korshak talked freely about his close friendship with Jake Arvey, and about Arvey's son, Irwin. Jake was "very ill" and had lost "3/4 of his stomach," but Jake was still alive and kicking political asses at this [Furfaro's] writing.

• Korshak was the "first person to be subpoenaed by the Kefauver committee to testify from Chicago," but "he was not asked to testify."

• He admitted that "he is a member of the Friars Club, but he is not proud of, nor does he go near the place. That the Friars Club is a 'cesspool.' That the members are not a social and charitable fraternity but a collection of gamblers who wager on anything if the odds are right. That he suggested that they seal up the Friars." This was a prescient observation, since, at the time—and for the next five years—the Beverly Hills Friars Club harbored a scam wherein many of Korshak's friends, including Harry Karl and Tony Martin, were being cheated out of many thousands of dollars each in rigged poker games, courtesy of a peephole drilled into the wall that allowed the cheats to pick up their "pigeon's" hands* The fix, which netted in the low millions, was run by Maurice Friedman, a real estate mogul and former owner of Las Vegas' New Frontier Hotel; George Emerson Seach; and Ben Teitelbaum. The inclusion of Teitelbaum's name in the scheme had to have been vexing for Karl, since Teitelbaum was Sid Korshak's partner in Affiliated Parking.

• In reference to the McClellan Committee: "Robert Kennedy and Pierre Salinger appeared in his [Korshak's] office, and questioned him about sweetheart contracts between unions and management. He appeared before the committee for one hour, and Kennedy questioned him again, and then thanked him for appearing."

• Korshak said that "he represents racetracks in the Chicago area. Mervyn LeRoy called him one day before the expected strike at Hollywood Park and asked him to help. He went to Hollywood Park, and met with twenty-eight attorneys from other racetracks, and union officials for the employees. The other attorneys resented his presence, but he was able to settle the strike for which he received a three-year contract. He maintained that this wasn't a sweetheart contract but that he merely brought union and management into accord through some of his contacts."

• Korshak admitted that he "was the legal counsel for the Duncan Parking Meter Company." He also admitted to his long and close friendship with Mai Clarke.

• He named some close friends (Dinah Shore, Cyd Charisse, Kirk Douglas, Debbie Reynolds, Harry Karl, etc.) and said "he uses his influence to get employment for his friends at the Riviera Hotel in Las Vegas. That he would rather not say anymore about Las Vegas."

Only when the agents brought up the Benny Ginsburg case did Korshak bristle. "Mr. Korshak became extremely angry at this point," the report states.9 Furfaro said that the only result of all this hard work was a lawsuit—against the IRS. "When we busted Ginsburg, we were sued out of Chicago," Furfaro pointed out. "I was sure Korshak was behind it. The suit dragged on for years and was eventually thrown out."

The Bistro

The L.A. grand jury investigation was just another one of countless bullets dodged by Korshak in his career, and his grand lifestyle was, typically, unaffected. In fact, it only seemed to become grander, if that was possible.

In the fall of 1963, Korshak was most often seen at a new upscale restaurant with French decor in the heart of Beverly Hills. Opening for business on November 1, 1963, the chic Beverly Hills eatery called The Bistro was at 246 N. Canon Drive, in the Beverly Hills business district. Korshak was an original investor (8 percent, or seven shares) when it was incorporated three months earlier. The restaurant was the brainchild of Oscar-winning director Billy Wilder* and local maitre d' extraordinaire Kurt Niklas. Niklas was a thirty-seven-year-old German Jew who had barely escaped Hitler's holocaust, then coming to America, where for years he was the maitre d' at Romanoff's Restaurant on Rodeo Drive, a magnet for Hollywood elite. When Romanoff's closed on New Year's Eve, 1962, Wilder, a Romanoff's regular, persuaded Niklas to open his own place. After Niklas obtained a thirteen-year lease for the Canon Drive storefront, he went back to Wilder. Niklas later recalled, "I went to see him and within twrenty-four hours he had checks in the mail for ninety thousand dollars."10 The sixty shareholders put up $3,000 each. The resultant $180,000 was deposited in Al Hart's bank—Hart was also among the original shareholders.11

For Bistro investor Sidney Korshak, the appeal of the place was obvious. In Chicago and New York, Korshak conducted his business in upscale eateries like the Ambassador East's Pump Room and the Cafe Carlyle. A creature of habit, Korshak liked to keep things simple, positioning himself in the center of activity, and usually within walking distance of his closest associates. The Bistro was at most a three-block stroll from them all: Paul Ziffren's and Harvey Silbert's law7 offices, both on Wilshire, Al Hart's flagship bank at Wilshire and Roxbury, Wasserman and Stein's MCA offices on Burton Way, and the two places Sidney used when he needed clerical assistance, the Associated Booking office on Brighton Way, and the Riviera Hotel booking office, also on Wilshire (#9571).

Korshak had known Niklas since 1956, having been introduced by a Las Vegas scion and associate of Mickey Cohen's, Moe A4orton, at a party Morton hosted at Romanoff's.12 Korshak quickly upped his investment to twelve shares, and by 1974, twenty-one shares, second only to Niklas (135). Besides Korshak, the investing partnership represented a who's who of the Hollywood "in crowd": Al Hart, Greg Bautzer, Jack Lemmon, Jack Benny, Dean Martin, Tony Curtis, Jack Warner, Robert Stack, Otto Preminger, Swifty Lazar, Frank Sinatra, and Doris (Mrs. Jules) Stein.

Site of Sid Korshak's "secret" office on Wilshire Boulevard (author photo)

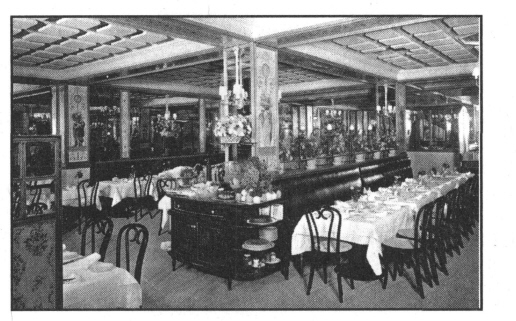

The Bistro (Marc Wanamaker/Bison Archives)

Wilder suggested the French motif after a film he was shooting at the time, Irma la Douce. When completed, the cozy cafe seated about ninety, with an upstairs room reserved for private parties. An early contribution of Korshak's was the retaining of Richard Gulley as the Bistro's "public relations consultant." Gulley, an old friend of Bugsy Siegel's, first gained work, a "walk around job," at Warner Brothers courtesy of a Siegel phone call to a Warners executive. In addition to his PR work for the Bistro, Gulley performed the same service for the Riviera in Vegas, again enlisted by Korshak. Over the years, Gulley's chief function seemed to be "girl procurer" for male celebrities and their studio executive counterparts.

The night before the Bistro's public grand opening on November 1, Niklas hosted a private opening-night black-tie dinner party for the restaurant's stockholders and their guests. Promptly at eight P.M., stars such as Dean Martin, Jack Lemmon, Polly Bergen, Louis Jourdan, and Korshak pal Tony Curtis joined studio moguls such as Walter Mirisch and Jack Warner. Sid Korshak's close friends such as Paul Ziffren, Alfred Bloomingdale, and Bel-don Katleman joined the festivities. "It was a happening," Niklas wrote. As for the Fixer, who was not known as a great partyer, he was his typical low-key self. "Sidney Korshak spent most of the party in the shadows, avoiding photographers," Niklas wrote. Interestingly, Niklas noted, "Sammy Davis, Jr. was conspicuously absent."13

After its November debut, the Bistro's regulars included Ronald Reagan, Paul Ziffren, Pat Brown, Lew Wasserman, Gray Davis, the Kennedys, Gregory Peck, Kirk and Anne Douglas, and Donna Reed—all friends and/or clients of Korshak's. Predictably, countless Hollywood movie deals and labor issues were concluded with handshakes across the Bistro's tables, while the VIP upstairs realm was the setting for the infamous scene in the 1975 movie Shampoo, wherein Julie Christie introduced Warren Beatty to oral pleasures available under the Bistro's tables.

Without doubt, the most coveted table was Table Three, in the corner just off to the left of the entrance. A profile of the restaurant in the Los Angeles Times noted, "At the end of the row is the 'lawyers' table. It's the only downstairs table with a phone. Frequenters are Greg Bautzer, Gene Wyman, and Sidney Korshak."14 At the request of a Howard Hughes girl procurer named Walter Kane, Niklas installed a telephone on the table. Director Alfred Hitchcock had his own opinion of those who commandeered the precious table. He told Niklas, "On an abstract level, the corner table is a metaphor for narcissism, the driving force that propels the cult of celebrity." Niklas agreed, adding, "The need to have the number one table is a territorial imperative, which can turn otherwise civil men and women into barbarians."15

However, both the table and the Hughes phone were soon appropriated by one of Howard's mortal enemies. The truth was that it was Sidney's table, much as Table One in Chicago's Pump Room had become his domain, and when it came to his table, Korshak betrayed a prickly thin skin on occasion, especially when it involved old rivalries. Once, when Korshak's attendance had not been anticipated, he arrived to discover that Hughes's aide Walter Kane was back sitting at his table, using the phone.

"Who the hell's at my table?" Korshak asked Niklas. When told it was an associate of the man who'd betrayed him in the RKO affair, Korshak turned on his heels and was not seen in the Bistro for a year.16

Kurt Niklas understood Sidney's protective attitude toward the table. "The corner table at the Bistro was his office," Niklas wrote in his autobiography. "He was in the restaurant so often that people would call and ask, 'Is the Korshak table available today?' He held court there like an errant pope."

The Bistro interior (Marc Wanamaker/Bison Archives)

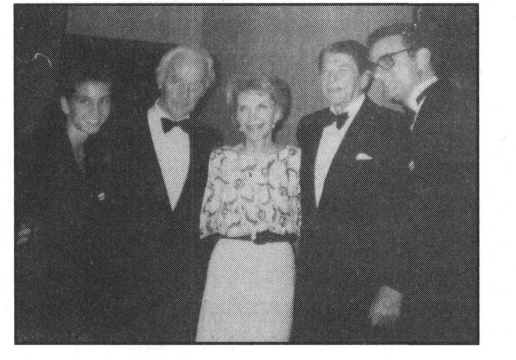

The Reagans at the Bistro with owner Kurt Niklas (second from left) (Mimi Niklas)

Korshak's daily routine was known to many. "He often ate alone at noon every day at the Bistro," said Hollywood AP columnist James Bacon.17 Casper Morcelli, who came to California after selling papers in Philadelphia for Moe Annenberg, became the Bistro's headwaiter from opening day until 1993. He recently recalled Sidney's modus operandi at the restaurant:

Sidney always came in by himself, early in the morning, before we opened the place. Sidney was well dressed. I never saw him with a tie askew. There was a jacket code there, so most of the patrons were well dressed.

He'd do his paperwork, or meet with the boss [Niklas], and then the people would start coming in to meet with him. I saw him every day of the week except Sundays. He didn't come for dinner much. He sat at the corner table almost every day.18

Original Bistro maitre d' Jimmy Murphy, who later opened his own popular restaurant, Jimmy's Tavern, well remembered Korshak's dietary regime. "He ate very simply," Murphy said. "In the daytime he drank iced tea. He'd eat a Bistro hamburger, or some grilled fish—very simple. Later in the day he'd have a bullshot or a martini or a glass of wine—he wasn't a big drinker. He always dressed immaculately, with silk shirts, and so on."19

Both Morcelli and Murphy have nothing but good memories of Korshak. "I loved him," Morcelli said. "He was very generous. He was so soft, yet so tough at the same time. He was just fantastic. He'd come up to me and say, 'How ya doin', Cas? Everything okay? The family okay?' He was there for anybody, even a busboy. He'd help anybody." Murphy's recollection was equally effusive: "He was always a gentleman and respected the help. He was a good tipper. At Christmastime he would give me a bundle of dollar bills. He'd take care of the chef and the others as well. He would always ask me, 'Jimmy, are you having any problems? How's the family?' I liked him a lot."

On one level, Korshak enjoyed the camaraderie afforded by the restaurant. "His Bistro table was like a movie set," said friend Leo Geffner. "He knew all the movie stars. The starlets would all come by and kiss his cheek."20 Hennie Burke, the current owner of Duke's Coffee Shop on the Sunset Strip, has been a social acquaintance of the Korshaks' for decades. "I knew Sid from the old days," Burke said. "We all traveled in the same circle with Pat Brown and the rest. I still play tennis regularly with Anne [Mrs. Kirk] Douglas and Bee Korshak over at Janet Leigh's house. We all used to go over to the Bistro after playing, and Sid would always be sitting at his table. He'd immediately send over a bottle of champagne for the girls." Burke's memory of Korshak echoes those of Murphy and Morcelli, and she sounded wistful in her description of him. "He was the most wonderful man—almost like an angel," she recently said with a tinge of emotion. "He was powerful, but he treated all his friends like family, which means he'd do anything for you."21

Timothy Applegate, longtime counsel for Korshak client Hilton Hotels, recently remembered having dinner with Korshak at his table: "I met him once for lunch and once for dinner at the Bistro. When I met him for dinner, Greg Bautzer was just getting up and leaving. Sidney sat down and said, 'I would have introduced you but you don't want to know that asshole anyway. He's got the biggest ego in Los Angeles.' I replied that I previously had been told that he had 'the biggest ego in the Western United States.' "22

What was most consequential about Korshak's Bistro days, however, were the business deals that were struck there—both face-to-face and over the phone. Niklas, Murphy, and Morcelli all remember Korshak's furtive conversations on the Table Three phone that soon came to comprise two lines, and the meetings with such corporate titans and political lions as Al Hart, Lew Wasserman, Paul Ziffren, Pat Brown, and Gray Davis. There were also confabs with "Dodgers people" such as Walter O'Malley and team manager Tommy Lasorda. Niklas wrote, "I personally knew two-dozen businessmen who paid him twenty to fifty thousand dollars a year for 'protection' from labor unions."

Often, Korshak's business benefited both his legit clients and his Chicago patrons simultaneously. Such was the case in 1963, when Korshak helped Lew Wasserman and the underworld, both of whom were facing exposure by one of America's best-known talents, and one of organized crime's most vocal opponents, composer and television pioneer Steve Allen. The Chicago native and creator of the late-night-talk-show genre became an outspoken anticrime activist in 1954, when he chanced upon a photograph of a man who had been severely beaten after speaking out against the installation of pinball machines in a store that was situated near a neighborhood school. Allen, under the threat of advertiser desertion, produced a two-hour documentary on labor corruption for New York's WNBT, from where his Tonight Show originated. After the show aired, one of the interviewees, labor columnist Victor Reisel, was blinded by an acid-thrower, and Allen endured slashed tires on his car and stink bombs set off in his theater. Then there came physical threats. One anonymous caller referred to the Riesel attack and told Allen, "Lay off, pal, or you're next."

But the hoods totally misread Allen, who was only emboldened by the threats. Over the years, Allen continued to take every opportunity to sound the clarion call against not only the underworld, but its Supermob enablers. Allen made frequent trips to Chicago, where he spoke at benefits for the Chicago Crime Commission, and his Van Nuys office contained over forty binders labeled "Organized Crime," holding thousands of notes and newspaper clippings.

But the entertainer's stance had a powerful impact on his career. "I was blackballed in many lucrative establishments," Allen recalled shortly before his death in 2000. "I was only invited to play Vegas twice in my entire career." This alone deprived Allen of millions of dollars from a venue he would have owned if given the opportunity.

In 1963, Allen was hosting the syndicated late-night Steve Allen Show when he received a call from Sidney Korshak. "I was asked to take it easy on Sidney's friends," Allen recalled. Not long after politely refusing Korshak's request, Allen felt the power of the underworld-Supermob collusion once again. "We had a terrible time booking many A-list guests for the show," Allen explained. It was clear to Allen that Korshak, in connivance with the Stein-Wasserman entertainment megalith, MCA, had chosen to deprive the Steve Allen Show of its talent roster, which at the time represented most of Hollywood's top stars. (A subversion by Korshak would have served two purposes since Korshak was also good friends with Allen's late-night competition at NBC, Johnny Carson.)

Despite the talent embargo, Allen concocted a wonderful program with his staple ensemble of brilliant ad-libbers such as Louie Nye, Don Knotts, Bill Dana, and Tom Poston, as well as quirky personalities like madman Gypsy Boots, and then unknown Frank Zappa, who appeared as a performance artist, bashing an old car with a sledgehammer. But Allen's 1963 run-in with Korshak would not be his last encounter with gangster intimidation.23

When Korshak's clients were unable to appear at Bistro Table Three, business was handled on his personal table phone. His Windy City pal Irv Kupcinet remembered Korshak's MO. "He could turn more tricks with a telephone call than anyone I knew," Kup said in 1997. At the Bistro, Jimmy Murphy remembered that some of Korshak's business dealings seemed to be more sensitive than others. "Sidney would get a call, then go outside to use the pay phone," said Murphy. Jimmy "the Weasel" Fratianno was among many who witnessed Korshak carrying a bagful of coins should he need to call his Chicago handlers, for whom he always used the pay phone in the lobby. It was widely accepted that Korshak used the untraceable pay phone to converse with Humphreys or Alex.

In later years, Korshak was seen being driven to even more secure locations for making phone contact.24 The L.A. police spied Korshak entering a Beverly Hills phone booth with a bag of coins, and making a series of calls. One of Korshak's favorite secure phones was located inside the legendary Drucker's Barber Shop on Beverly, just north of Wilshire.25 Like others, Hilton Corporation counsel E. Timothy Applegate, who was the liaison between the company and Korshak for many years, heard the stories of Sidney's clandestine forays to Drucker's. "I was later told by a union guy that once a week Korshak would go down to Drucker's Barber Shop and meet with local mobsters," said Applegate.26

Proprietor Harry Drucker had come to Beverly Hills from New York in the 1940s, the move financed by his pal Bugsy Siegel.27 In New York, Drucker was Siegel's and Frank Costello's barber in Arnold Kirkeby's Waldorf-Astoria, where Joe Kennedy was occasionally seen accompanying Costello for a trim. When Bugsy moved to Beverly Hills, he took Drucker with him. As a favor, Drucker also set up the barbershop at Vegas' Tropicana Hotel, which was partially financed by Costello.28

Beverly Hills native Don Wolfe, whose stepfather Jeffrey Bernerd copro-duced Alfred Hitchcock's early films (The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps), was a Drucker's regular and has vivid memories of the popular tonsorial parlor: "The shop was upstairs, above Jerry Rothschild's Men's Shop, where Bugsy got his suits and jackets. Drucker's had a reception desk on the first floor, and you had to be buzzed in to go up to the barbershop. I later learned that it was because Drucker's was also a bookie joint." Wolfe recalled that Drucker's possessed one amenity that significantly added to the attractiveness of the shop. "There was a glassed-in barber chair with a phone in it," said Wolfe. "Bugsy got his hair cut there almost every other day it seemed. I saw Bugsy there often using that phone. Drucker told me that Bugsy used that phone because he suspected his phone was tapped. When they moved the barbershop to Wilshire, they moved the glassed-in booth as wTell." Over many visits, Wolfe saw other notables using Drucker's secure hotline, including Ronald Reagan, Elvis Presley, and Earl Warren.29 Johnny Rosselli was also known to be a fan of both Drucker's haircuts and his enclosed booth.

Not all sensitive Bistro conversations were conducted by phone or at Table Three. On occasions, Korshak's business was taken outside. "He was a very low-key guy for a very powerful man," said Jimmy Murphy. "Sometimes he would go to the little bench we had outside for a very private conversation." Casper Morcelli also remembered how Korshak liked to take frequent strolls in the tony Beverly Hills neighborhood: "He used to walk a lot after lunch—he knew the whole of Beverly Hills." Longtime NBC investigative producer Ira Silverman saw the walks as part of a long tradition of hoods who preferred to discuss business where they couldn't be watched. "Sidney would take a walk, much like the boys in New York do," opined Silverman.30

One of Korshak's most frequent lunch companions was Andy Anderson, head of the Western Conference of Teamsters. Anderson had started working for the Teamsters in 1954 and rose in the hierarchy, slowly becoming the man Korshak associated with and with whom he finalized legal issues after Hoffa was sent to jail. "We'd negotiate with Sidney on the parking lot at the baseball stadium, the racetracks, the liquor industry, the breweries, the food industry, the motion picture industry," said Anderson.

Anderson and Korshak first met in the 1960s, when Anderson was called upon to negotiate a Teamster warehouse contract with discount-shoe magnate Harry Karl, who brought Korshak along as his counsel. "Sidney would talk, but he was careful of what he said," Anderson remembered. "He was careful of who he sat with when he had lunch. I noticed—he didn't have to tell me—I could see it." The friendship grew over years of doing business together. "When I was the director of the Teamsters in the Western Conference, I even hired one of his sons to do some work for us," Anderson recalled.31

Most importantly, Korshak introduced Anderson to Lew Wasserman, and the threesome often met secretly at Korshak's home to nip labor problems in the bud before a strike could ever rear its head. The trio celebrated their friendship with an annual lunch at The Cove, in the Ambassador Hotel. 32 "The Teamsters never struck Lew," Anderson declared. "And it was because of Sidney."

F. C. Duke Zeller, who wrote DeviVs Pact: Inside the World of the Teamsters Union based on his experiences working as government liaison and personal adviser to four Teamster presidents over fourteen years, recently said, "Virtually every Teamster leader on the West Coast, in the Western Conference, answered to Sidney Korshak. Everything and everybody went through him out in Los Angeles."33 Andy Anderson disagreed with the analysis. "Sidney's and my acquaintance progressed to an equal and cordial working relationship," Anderson stated.34 I definitely came to attention when he called me, but he never asked me to do anything untoward and was of assistance to me many times. Sid always watched out for me—in the sense that he would say, 'If there's somebody you're confused about, tell me and I'll let you know.' And he used to do this, but he never told me what I had to do; he told me what not to do.35

Occasionally, Korshak's dining partners fell into categories far below those of the typical Beverly Hills habitue. Jimmy "the "Weasel" Fratianno has written of meeting Korshak at Table Three; Johnny Rosselli and Moe Dalitz also broke bread on occasion with Korshak. "I saw Sid and JR [Rosselli] together many times," said Rosselli's goddaughter, actress Nancy Czar. "They were either at Chasen's or the Bistro. They knew each other from Chicago."36

Gianni Russo, who had been delivering messages from the Eastern bosses (e.g., Costello, Accardo, and Marcello) to Korshak at Chicago's Pump Room, now did the same at the Bistro. "There were about four key guys in this country, and Sid was one of them," recalled Russo. "He was connected to everybody. I used to sit at his table at the Bistro and never paid a dime. He would never conduct business in his house. None of those guys ever did. Nobody could understand it—I was a young kid then, delivering these messages—I don't even know what they were. But Sid was an amazing man. A lot of times we'd have to sit and wait, so we'd have coffee and talk, and he became like a mentor to me. He just felt I was a nice kid and didn't know what I was doing around these people. He was usually drinking Jack Daniel's or Scotch."

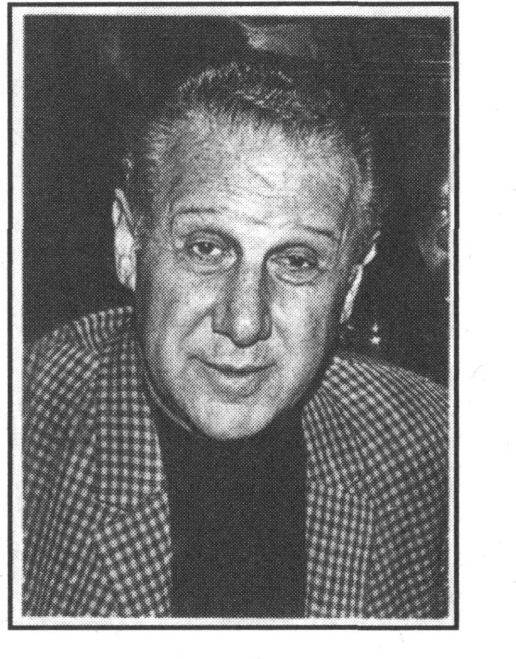

Korshak at a Paul Ziffren soiree (Dominick Dunne)

Like everyone else, Russo was impressed with Korshak's impeccable appearance. "Sid was a gentleman and a great dresser," said Russo. "He taught me how to dress. I used to wear the gold chains—what they call the wopsi-cle." And just as he had displayed his interest in watches to Shecky Greene in Vegas, Korshak expressed it again to Russo. "Pick one good watch," Korshak said. "Forget everything else." When it came to appearances, the Fixer emulated the dashing Wasserman, one of whose favorite expressions was "Dress British, think Yiddish." Korshak's sartorial expertise was fully appreciated by the young gofer. "It was because of Sid that I cut out that New York gangster bullshit," Russo said.*'37 Leo Geffner was also impressed with Korshak's attention to sartorial detail. "Sidney was always impeccably dressed—the best suits," said Geffner. "I never saw him without a tie unless he was home, and even the sport shirts he wore at home would have been the three-hundred-dollar kind."38

Jimmy Murphy recalled some of the less than savory associates who met with Sidney at the Bistro: "He also met with some strange, shady-looking people at the Bistro. Sometimes they would go to the private room upstairs for lunch. Sometimes people just dropped off envelopes for him. There's no record of that, that's for sure." In his Bistro lunches with Korshak, Anderson recalled sometimes being joined "by these characters. Sidney would introduce me, and he'd say about me, 'He's okay, we can talk in front of him.' Then, after they left, he'd say, 'You never met them.' "39

Regardless of the rubric, when a deal was eventually consummated, Korshak's bills were discreetly mailed from his brother Marshall's Chicago law office. Often he would get paid in cash or with barter—like new cars.

The Untouchable: Invulnerability in Sidney's Fortress

Local FBI man Mike Wacks recently recalled how he became aware not only of Korshak's Bistro companions, but also how Sidney represented virtual immunity from prosecution. "Supposedly, we never had enough PC [probable cause] to wire up the Bistro," said Wacks. "Korshak was real easy to pick up over at that restaurant because he would hold court there. If we weren't doing anything, we'd go over there and see who he was having lunch with. He had the same corner booth. He had a certain time. And it was always there for him. As a matter of fact, when wre were in there one time, he was using the phone on the corner table and I said, 'God, I can't believe we couldn't get PC for this thing.' We couldn't. And this is one of the primary booths in the place. I can't even recall the exact guys who came in to see him, but they were righteous guys from Chicago, they were made members of the Mafia. It wouldn't be unusual for Sidney to meet with those guys or be seen with them, but he was Teflon. The police would identify these guys and they would go to Korshak, and Korshak would more or less tell them to pound sand—it was his business. He got away with it. Nobody ever questioned it. I mean, we questioned it, but we never could get anything going."40

Among other obstacles was Korshak's professional status. It seems that when Jake Arvey advised his wards to obtain law degrees, he was well aware of the ancillary benefits that particular sheepskin provided. Not only could their legal knowledge force the feds to play by the rules, which they often ignored, but with all their conversations with hoods protected by the attorney-client privilege, damning evidence was more deeply hidden than the proverbial needle in a haystack.

Chicago FBI agent Bill Roemer was one of many who understood the challenge represented in investigating Korshak and his ilk. "There was an FBI control file kept on Korshak: No. 92-789, the prefix designated racketeering and the last number was assigned sequentially," Roemer said in 1997. "To my knowledge, we never went out and conducted any real investigation on Korshak. We just never investigated lawyers in those days. The FBI was made up predominately of lawyers."41

Fran Marracco, wrho succeeded Roemer in the Bureau's Chicago Field Office, echoed his predecessor: "You can't run an OC [organized crime] case without running into cops and politicians. It is very hard to bring cases against them. So many people's jobs depended on them that you're not going to find witnesses. Nobody wants to torpedo their career."42

The sensitivity was no less apparent in Korshak's West Coast dominion, where A. O. Richards, an FBI agent from 1947 to 1977, hit the same Korshak brick wall in L.A. "He was almost an untouchable," Richards agreed. "You couldn't go after him, he was too well protected. Who would dare wiretap Korshak?"43 Some law enforcement professionals chalked up the inactivity to innocent bureaucratic difficulties. G. Robert Blakey, at the time an attorney in Bobby Kennedy's organized crime section of the Justice Department, said, "The legal problem of doing a direct investigation of a lawyer is a nightmare. A crooked lawyer in our society is almost beyond reach, the way it is organized today."44 Chicago-based U.S. attorney in the organized crime division David Schippers recently explained, "You need accountants to go through books. The FBI didn't have accountants. It was a matter of evolving. It took a long time for the FBI to adjust to it. It took the government a long time. It started in the thirties with gangsters, bank robbers. Officials were reacting to murders, violence. Then during the war, we're chasing spies. After that came Kefauver and then the rackets hearings. Then somewhere along the line you understand that politicians are in on this too. There are sweetheart deals here."45

RFK's Department of Justice colleague, Adai Walinsky, as noted, wrote off the official inaction to being merely a case of "investigative evolution"; 46 however, others weren't so forgiving of the feds' performance in relation to the Supermob. One senior FBI official in Los Angeles, who requested anonymity, cut to the chase, saying, "I think the Bureau was a little bit afraid of investigating Korshak because he had so many connections, and he was connected with so many top people out here in the movie industry. I think they were kind of afraid that if the word got out we were working a 92 case on him [organized crime investigation], all hell would break loose. It was the same way with Sinatra. I personally opened a 92 case on Sinatra. We just started to do a little bit on that and then the Bureau said to close the case."

Chicago's Fran Marracco agreed: "The Korshaks had connections in Washington. We were often cut off from pursuing them by headquarters. The U.S. Attorney's Office would just stall everything. They didn't mind if we went after some small-time local paisans. You're better off busting a bookie." As to exactly why headquarters would derail investigations of the Supermob, many point to J. Edgar Hoover's known friendship with the likes of Al Hart, the Korshaks, and other questionable operators. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy was likely torn because of his own family's relationship with the Korshaks in Chicago and Los Angeles.

Often, local FBI field agents took it upon themselves to monitor people like Korshak. Once, when Mike Wacks heard through an authorized wiretap of Allen Dorfman that Korshak, Dorfman, and Andy Anderson were to have lunch at the Bistro the next day, Wacks planned an eyeball surveillance. Posing as an insurance salesman, Wacks landed Table Four and overheard Korshak ask of Andy Anderson, "Have you got the money for Lou [phonetic]? I'm going to have dinner with him tonight." Anderson then handed Korshak a large envelope, which he immediately stashed in his inside coat pocket. Wacks was of the strong opinion that "Lou" was in fact Lew Wasserman, and that Anderson and Korshak were just doing business as usual, preventing Teamster strikes at Wasserman's Universal Studios.47 According to Wacks's memo memorializing the surveillance, Allen Dorfman showed up soon thereafter to join the party.48

There remained other agencies that could have pursued the Supermob, such as the newly established Organized Crime Strike Force. This group of regional Justice Department investigators was formed in 1966, but had a checkered history over the next two decades—again with little support from its Washington overseers. Marvin Rudnick, an attorney in the Los Angeles Strike Force from 1980 to 1989, recently described the workings of the unit: "The way this thing worked was that the Strike Force was made up of lawyers who specialized in complex litigation. Cases would be presented to us by the FBI, IRS, ATF, et cetera. And we would represent them in court. We wouldn't start our own investigations."49

But the Strike Force was likewise impotent in the face of Supermob associates like Sidney Korshak. L.A. FBI man Mike Wacks, who often turned such leads over to the Strike Force, recently described the problem: "The Strike Force was very reluctant because Korshak was an attorney. It was very hard back then to get wiretaps against attorneys. It was almost like an act of God. That would have been a wealth of information."50 L.A. Strike Force attorney Rudnick was also frustrated over the lack of official interest in Korshak et al. "There were no projects on Korshak that I'm aware of, and I'm a little surprised at that," Rudnick said. "We should have dealt with him, but we would have only dealt with him if the FBI dealt with him. To me, Korshak would have been the best target in town for organized crime prosecutors. I've been in L.A. for twenty-five years, and I've never seen where anybody has tried to take down that level of criminal. They took down the L.A. 'family' which was locally important, but that was it."

The situation was mirrored in the Strike Force's Chicago headquarters. David Schippers, who headed the Chicago Strike Force in the 1960s, remembered the obstacles. "Korshak was never on our radar because Teamster stuff was being handled out of Washington," Schippers said in 2004. "We were more interested in the Italian connections. So Korshak skated. He certainly had friends in Washington. When I first started with the Strike Force under Bobby Kennedy, I asked him, "What about Korshak?" He said, 'We're handling it out here [in D.C.].' But Korshak had political ties everywhere, and he was nonpartisan."51 Fellow Chicago Strike Force member Peter Vaira agreed, saying, "The U.S. attorneys and the Strike Force were told to stay with the traditional gunslingers because the white-collar guys had political power."52 One could reasonably assume that the Labor Department would have had a serious interest in Korshak's Teamster (and other union) machinations. However, such was not the case. Chicago-based crime investigator for the Labor Department Tom Zander described his department's inaction: "We were told by the Washington office not to go after Korshak. 'You can't do that. That's it,' we were told. He must have had a connection in Washington, because such a thing wouldn't have been possible without it. He had contacts in the Illinois judiciary, federal, state—you name it."53

Things were no different for IRS investigators. Former IRS Western Region organized crime investigator Andrew Furfaro recalled, "We got zero support from headquarters. The local agents took it upon themselves to follow these guys, and we did. We sent our reports up the chain, but nothing ever happened. I'm sure political connections had a lot to do with it."54

With the federal elite showing little interest in Korshak, it was left to the state agencies to work his case. But they were similarly hamstrung, with no one really expecting local district attorneys to move against the Korshaks of the world. As Peter Vaira explained, "Most of the time, the local DAs don't

touch those cases—you get elected with fires, rapes, and murders." Connie Carlson, an investigator for the California State Attorney General's Office, was personally interested in the white-collar types like Korshak, Hart, and Ziffren. However, despite great leads and legwork, and after many years on the job, Carlson's tenure ended in frustration. "There was not enough manpower to prosecute these men," Carlson said. "The FBI wouldn't share their information with us, so we just hoped the IRS would get them."55

John Van DeKamp, L.A. district attorney from 1975 to 1983, and the state attorney general from 1983 to 1991, recently admitted his lack of interest in Korshak. "I don't remember any open investigations of Korshak, but his name just kept cropping up in all these labor settlements," Van DeKamp said. "I do not remember Korshak ever being a target of our office. The intel guys might have been interested, but it never got up to me, so they never made a case. There were rumors, and he was a mysterious figure." Interestingly, Van DeKamp readily admitted his friendship with Korshak pal Paul Ziffren: "When I first ran for Congress in 1969,1 was told that I should talk to Paul Ziffren, who gave me a little money to run. We were friendly over the years until he passed away."56

It has been alleged that Van DeKamp's friendships with the former Chicagoans and his concern with the political sensitivity of his office may have played a role in the scuttling of worthy cases. James Grodin, an organized crime investigator in Van DeKamp's office, was, like Carlson on the state level, frustrated by the lack of movement on the Chicago crowd. He was equally disturbed by what he saw as a wholesale trashing of good leads. "John Van DeKamp purged a lot of the DA's files," Grodin recently said. "I was warned in advance, so I copied some of mine before they were trashed. One night they came in with a dolly and carted off the file cabinets. Other DA's were even worse, and really did a number on the office's files."57

With Beverly Hills and the Bistro, Korshak had re-created not only a Lawndale-like, close-knit environment, but an establishment that mirrored his Chicago Pump Room "office." Korshak's daily appearances at the Bistro became so predictable that any absence became a cause of concern for owner Kurt Niklas. Once when Korshak failed to show for a few days, Niklas asked him, "Sid, where you been?"

"Sicily," Korshak replied.

Niklas then had the temerity to push the subject. "What the hell were you doing in Sicily?"

"Don't ask stupid questions!" was Korshak's terse answer.58

Just two days after the Bistro's gala November 1 opening, Korshak's world began to be rocked by a series of tragedies. On November 3, Sidney and Marshall lost their eighty-year-old mother, Rebecca, who had been living in Chicago's kosher nursing home, Alshore House.59 Not three weeks later, the Korshaks and most other Americans mourned the death of President Kennedy, gunned down in Dallas on November 22. Kennedy's assassination was likely more painful to the Korshaks than most due to the family's personal acquaintance with the Kennedy clan. But November held still one more misfortune for Sid Korshak: on November 30, Karyn Kupcinet, the troubled daughter of Irv Kupcinet, Korshak's longtime Pump Room companion, was found dead at age twenty-two in Los Angeles, where she was pursuing a career as an actress, and it is all but a given that Korshak had opened some doors for the aspiring movie star with his powerful studio friends.

Throughout much of her young life, Karyn had been obsessed with her body image, and her weight typified the yo-yo fluctuations that go hand in hand with diet-pill abuse. Although the coroner ruled the death a murder by strangulation, some have found errors in his work and believe the death to have been a suicide by overdose, especially when a recent ditching by her boyfriend is taken into account.

Ever the loyal friend, Sid Korshak hastened over to the morgue and identified the body, said Louis Spear, circulation manager for Kup's Sun-Times. "When Kup's daughter was killed, I had lunch with Sidney and the Beverly Hills police chief," recalled Korshak friend Leo Geffner. "He was pushing and urging them to conduct the investigation. Sidney offered to help out any way he could. He even offered to put up reward money."60 According to Kup's son Jerry, Korshak even offered to send his Chicago mob associates to L.A. to help find Karyn's alleged killer, if one in fact ever existed. Other sources noted that Sid later prevailed upon the local police to suspend the investigation, reasoning that it might dredge up information about her drug-abusing lifestyle that would be hurtful to Kup, who was said to have been suicidal himself over the loss of his beloved daughter.61

Although the year's final insult to Korshak's world did not involve him directly, few doubt that he counseled the victim, and it is known that his Supermob compadre Al Hart played a hands-on role in the affair.

On Sunday, December 8, Frank Sinatra's nineteen-year-old son, Frank Jr., was kidnapped at gunpoint in his Harrah's Lodge hotel room in Lake Tahoe, Nevada, where he was performing. The three young, bumbling kidnappers contacted Sinatra the next day and delivered their demand for $250,000 in ransom.62

According to concert promoter and celebrity photographer Ron Joy, who dated Frank's daughter Nancy in the sixties, Sid Korshak advised a distraught Frank senior to contact everyone's favorite banker, Al Hart, who had a penchant for laying his hands on quick cash.63 All day Monday and into the night, Hart oversaw the counting and photographing of $250,000 (minus $15 for a briefcase to carry it in).64 On Tuesday, Hart met Sinatra and the FBI at Korshak's Bistro at two in the afternoon, and after downing a stiff Black Jack, Sinatra proceeded to LAX for the payoff. On Wednesday, Junior was released in Bel-Air, and by Thursday the kidnappers were in jail.

The next day, Sinatra was back at the Bistro for his forty-eighth birthday. After everyone sang "Happy Birthday," Sinatra told Niklas, "I'm just glad it's over with. Gimme a shot of Black Jack."65

*Snowball was killed soon after President Nixon's 1969 inauguration by Attorney General John Mitchell. Mitchell explained his action by saying merely that the businessmen had promised never to do it again (Messick, Politics of Prosecution, 91). IRS agent Cesar Cantu added that the investigation had been extremely sensitive because of all the local Los Angeles politicians involved, and that the IRS later destroyed all of its records related to Snowball (Andrew, Power to Destroy, 142).

*Among those cheated were Harry Karl ($80,000), Tony Martin ($10,000), Zeppo Marx ($6,000), agent Kurt Frings ($25,000), Ted Briskin ($200,000), and actor Phil Silvers (undisclosed amount). Others lost even more.

*Wilder had garnered a staggering six Academy Awards and helmed such hits as The Lost Weekend, Sunset Boulevard, Stalag 17, The Seven Year Itch, Some Like It Hot, and The Apartment.

*Dick Brenneman, who lunched with Korshak in 1976, recalled a similar Korshak nod to the importance of appearance, when Korshak proudly displayed a dazzling diamond on the little finger of his left hand. "Absolutely flawless, and the finest color," Korshak puffed. "It cost me sixty thousand, but I could sell it today for twice that."