THE YEAR 1968 saw Sid Korshak once again building a consortium with a grand vision, but, like his RKO experience, this one fell short of its goals. The labyrinthine concept, to build a tower of private condos, came via the man who'd introduced Korshak to Kurt Niklas years earlier, Moe Morton, an entrepreneur with a checkered background, to say the least.

After moving to L.A. from Chicago in the forties, when the Supermob made its inroads into California real estate and entertainment, Morris "Moe" Morton became a well-known San Diego bookie associate of L.A. mobster Mickey Cohen and a long-term friend of both Meyer Lansky's and Bugsy Siegel's. For a time, he was barred from Hollywood Park Racetrack, while his brother Jack was permanently barred from all California tracks after it was learned that he was running a book operation at Al Hart's Del Mar facility, obviously with Hart's blessing.1 (In those days, "on track" bookies were a common convenience that allowed large wagers and wins away from the IRS's prying eyes.) Moe was once imprisoned for defrauding the Carnation Milk Company out of $250,0002 and was also known to be a courier for the Las Vegas skim, which he moved through Mexico.3 It is believed that this skim smuggling was linked to the Mai Clarke/Mexican-parking-meter money laundering (see chapter 12).

Morton also had a residence in Acapulco, the home of his American wife, Helen, who'd grown up in Mexico, where her father was employed as an engineer. Helen, in turn, had gone to grammar and high school with the former president of Mexico Miguel Aleman Valdes, whose corrupt regime's links to Meyer Lansky would give Morton the idea in 1966 to build a retreat for hoods, where they could relax, make deals, and otherwise go on the lam from their pursuers in the United States. Of course, one of Morton's silent investors in the condo construction would be Lansky, and as for the requisite "owners of record," Moe turned to his Bistro buddy Sid Korshak to reel them in.

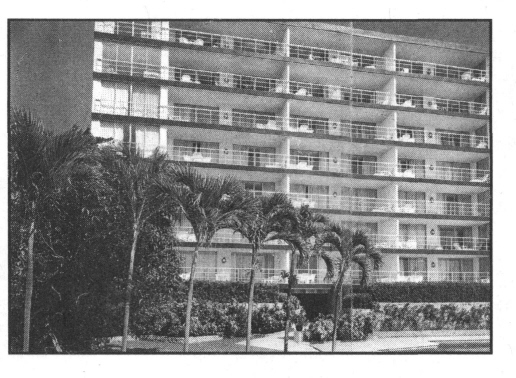

The Acapulco Towers (author photo)

According to confidential sources, the prequel to the new scheme occurred when Meyer Lansky helped elect Aleman the president of Mexico in 1947 by advising him and paying for his campaign. Lansky's quid pro quo was essentially "You become president of Mexico and the first thing you do is make sure that they do not try to legalize gambling in Mexico." Lansky was merely trying to assure the success of the nascent Las Vegas, where he was bankrolling Bugsy Siegel, among others. Mexican politicians were notoriously corrupted; during Aleman's term, there was a national lottery scandal (1947-49), when Mexican senators were openly bought by mob money. Such massive corruption was tolerated because at least some of the payoffs were rechanneled into local investments. One prominent Acapulco businessman said in 2005, "The Aleman family holds a tremendous fortune; he stole a lot of money, but he did a lot for the country."

Aleman supposedly took millions from Lansky in bribes and lived up to his end of the no-casino bargain. Regrettably for Aleman, Mexican law dictated just one six-year term in office for the President, so to ensure his continued power, Aleman created the powerful President of Tourism position for himself—with no term limit. Over the next few decades, the bribing of Mexican politicians almost put Chicago to shame, and Aleman was said to wield so much behind-the-scenes power that he virtually appointed his presidential successors. Locals alleged that Aleman "owned Acapulco" in the 1960s.*

With Aleman's and Lansky's blessing, Morton began work on his relatively modest "hotel," bringing in two Mexican investors, a Mexican manager named Porfiro Ybarra, and L.A. contractor Brewster Stevens. The new corporation was christened Satin (or Satan, depending on whom one believes), named after a deceased Morton dog. Morton bought the land for $110,000 and brought in Beverly Hills real estate developer (and owner of Kahlua Liqueur) Jules Berman, who put up an additional $400,000. And as per Mexican custom, a good portion of the money ended up lining the pockets of corrupt local pols. When U.S. investigators conducted interviews two years later, they interviewed hotel staff who told them, "On numerous occasions, various types of Mexican officials came to the hotel, and instead of conforming with business practices and standards in Mexico, Mr. Morton would choose to bribe those officials in their official capacity."4 At the time, it was illegal for aliens to own land in Mexico, so to guarantee a waiver of the statute, certain pols were typically taken care of.5

The property was located in the hills overlooking Acapulco Bay, where Morton first instructed Stevens to build a warehouse so that Morton could store construction items—doorknobs, appliances, silverware, and other furnishings—smuggled from the United States and transshipped on his own fifty-one-foot yacht.6 During the hotel's construction, Morton freely boasted to Stevens, his son James, and others that he was the skim "bagman" for the Outfit in Las Vegas and was close with many other hoods.7 "In no way did Mr. Morton try to be secretive about the fact," investigators were told.8 The real estate agent who sold Morton the property said recently that he had no doubt that Morton would make such a revelation. "Moe was a well-known blowhard," the agent said.9

What Stevens couldn't know were the ultimate origins of his paychecks. Agents of the Illinois Bureau of Investigation later testified that Morton, as an "associate of big name mobsters and courier for transfer about the country of money skimmed off the top of Las Vegas gambling income, [who] formed a Mexican corporation to buy the land, got American businessmen to put up the money, then squeezed them out at 50 cents on the dollar." According to the investigators, Meyer Lansky, Sam (Momo) Giancana, and Sidney Korshak "were around the edges of the transaction."10 This echoed what Johnny Rosselli told his goddaughter, Nancy Czar: "The Acapulco Towers was built with Vegas skim money."11

Before the condos opened, Morton had a disagreement with one investor and bought him out, as noted, for fifty cents on the dollar; the other investor, Jules Berman, who argued with Morton over the wisdom of bribing the local officials, was thrown bodily out of the hotel. Morton then turned to Korshak, described the operation, and invited Korshak to put together one of his famous investment groups and join the action. Korshak, who already maintained a villa on Pichilingue Beach near Acapulco, liked what he heard. Thus, in 1968, Korshak and Morton formed a new corporation named Simo, for Sidney and Moe.

By October 1968, Korshak had convinced ten friends to invest $50,000 each for what most believed to be a private time-share, although it is highly unlikely that Korshak apprised his L.A. pals of the hoodlum connection. There were a number of familiar faces among the investment group: Al Hart and a banking partner, Alfred Lushing; Delbert Coleman; Greg Bautzer and Eugene Wyman; Gulf 's Philip Levin; actress Donna Reed and her husband, Tony Owen; Eugene Klein, the owner of the San Diego Chargers; and brothers Nathan and Gerald Herzfeld, owners of Yonkers Raceway in New York.

Korshak later told the SEC about his investors: "These were all people who had visited from time to time in Acapulco. This is a place that was probably built for condominiums, and we all felt that if we bought this thing, that maybe we would each take a condominium. It is only twenty apartments . . . We had a fifty percent interest."12

One of the most interesting of the new names was Philip J. Levin, the same Levin who had recently become a major investor in Bluhdorn's Gulf & Western and ran that company's real estate arm, Transnation. But Levin was anything but a mild-mannered real estate speculator and corporate executive. The son of a minor loan shark, Levin was a Rutgers Law School graduate who lived in Bethel, New Jersey, and had made over $100 million as president of Philip J. Levin Affiliated Companies, which comprised thirty corporations and real estate holdings in California and Florida. Much of the land he had sold in Florida was to "syndicate figures."13

Phone records revealed that in one month, someone in Levin's home had over thirty-five phone conversations with someone in the home of Angelo "Gyp" DeCarlo, a lieutenant in the Genovese crime family, one of the top five Mafia families in the country.*'14 Other calls were traced from Levin to DeCarlo's partner Sam "the Plumber" DeCavalcante. (Levin later testified that his son Adam was gabbing with DeCarlo's son, Lee—but he was never asked about the DeCavalcante calls.) Federal investigators were certain that Levin's fast rise in real estate was financed by Meyer Lansky, and that Levin figured prominently in both DeCarlo's and Lansky's operations.

Levin later testified that he first met Morton in February 1967 when Levin spent a week in Acapulco with Twentieth Century-Fox mogul Darryl F. Zanuck.15 Levin said he met Korshak there around the same time. "He had a house there and I visited it one night and met him for the first time," Levin testified. "[Al] Hart acted as negotiator for the hotel. And on the advice of Korshak I entered into the venture." Levin said Korshak and Hart approached him with an offer to purchase a 5 percent interest in the hotel for $50,000.

When completed, the Acapulco Towers was a far cry from the opulent Kirkeby-owned Hilton at the base of the mountain. Jack Clarke, who later traveled to Acapulco to investigate the ownership of the condos, recently described the layout: "It was toward a mountain, and this is about a half a mile or a mile from the Hilton, which is on the main strip. You go up the side of a mountain—I found out later I drove right by the place, didn't even know it was there. Then I came back and I see a tiny sign, ACAPULCO TOWERS, and sure enough, there it was."16 Clarke described a gray, seven-story building, comprising fourteen three-bedroom apartments and seven with one bedroom, a swimming pool, and a garden. As another investigator put it, "Hardly a place to get lost in the lobby."

Once the doors opened, the Towers welcomed its celebrity owners and their friends. Manager Ybarra said, "There was a steady stream of Hollywood personalities coming to the hotel as soon as it was open." The place was empty for the majority of the year, but when it did function, it played host to many of Korshak's best Hollywood friends, such as Tony Curtis, Tony Martin and Cyd Charisse, Kirk Douglas, MGM honcho Kirk Kerkorian, and, of course, Robert Evans. Reservation cards retrieved later showed that Marshall Korshak was also a regular guest at the hotel. Co-owner Eugene Klein told author Dan Moldea, "We used to go down there. We used to bring our own food. We swam in the pool. We cooked hot dogs and hamburgers. It's not even a real hotel. It's an apartment hotel. We spent three, four days in the sun. And then we went home."17 Ybarra later told investigators, "It was never really operated like a hotel. It was in essence just a private club."18

Hollywood gossip maven Joyce Haber described a week of partying in Acapulco, in which guests such as Gene Klein, Eugene Wyman, the Korshaks, actress Merle Oberon, actor Noel Coward, CBS honcho William Paley, and MCA's Milton Rackmil bounced between the home of host Miguel Aleman and Moe Morton's Acapulco Towers.19

Haber's and Klein's bucolic descriptions, however, are far from the complete story of the Acapulco Towers. An investigation two years later found that during the "off-season," the hotel became a meeting place/hideout for some of the most notorious organized crime bosses of the era, including Meyer Lansky, Sam "Momo" Giancana, and a host of underworld heavy hitters from Canada. They used the place for relaxation, to make deals, and go on the lam when things were hot across the border. Alberto Batani, one of the original Mexican investors in Satin, told investigators, "There were several people who didn't like newspaper publicity and who would like to, in essence, hide out at the Towers."20

Batani and others reported seeing Morton entertaining Sam "Momo" Giancana on Morton's yacht in Acapulco Bay, a craft that Morton later sold to another Moe—Dalitz. Giancana was living in Mexico at this point, having been banished from Chicago by Accardo. Interestingly, Morton's company also went by the name Meymo, which could be seen as a contraction of Meyer and Momo. Likewise, Meyer Lansky was seen there "numerous times" with his "associate and confidant" Hyman Siegel. Moe Dalitz was also a frequent guest.

In February 1970, Canadian authorities monitoring the movement of that country's organized crime family, the Cotronis, reported on a virtual underworld convention at the Towers, ostensibly to conduct some business involving Canada's liquor scions, the Bronfman family. They reported that Sid Korshak was there with Meyer Lansky, his attorney Moses Polakoff, and Frank and Vincent Cotroni, Paul Violi, Leo Berkovitch, Raymond Doust, Anthony "Papa" Papalia, Frank Pasquale, Newton Mandell (of Transnation), Del Coleman, Tony Roma, Phil Levin, Irving Ellis, Jimmy Orlando, Pino Catania, and Angelo Bruno. The group's first meeting was held in the Acapulco home of Canadian gangster Leo Berkovitch. Two weeks later, Playboy's Hugh Hefner and offshore investment wizard Bernard Cornfeld were also seen there.21

Coincidentally, during one of the off-season bookings, a relative of a Los Angeles investigator in the DA's office, Jim Grodin, witnessed a telling tete-a-tete. "My cousin Sam was in Acapulco with his wife when he met Al Hart on the Acapulco Towers balcony with Lansky," said Grodin. "Hart introduced Sam and his wife to Meyer, and they took a photo together." When Sam relayed this to his cousin, Grodin went back to his office and ran a criminal-history workup on Hart. "I learned that he went to prison in the thirties for some kind of land fraud in San Bernardino," added Grodin. He also learned that many L.A. investigators believed that Lansky was a silent partner in Hart's City National Bank.22

During a 1970 investigation of the Towers, the chairman of the Illinois Bureau of Investigation, Alexander MacArthur, appropriated W. Somerset Maugham's description of Monaco when he said of the facility, "This is a sunny place for shady people."23

More Fun with Sidney, Delbert, and Phil

Soon after their ill-fated Acapulco partnership began, Korshak, Del Coleman, and Phil Levin initiated another phase of the scheme. This gambit involved a Korshak-orchestrated takeover by Del Coleman of a California company, then manipulating its stock by announcing pending mergers and purchases of a number of Vegas casinos, namely the Riviera and Stardust. They would then swap the inflated stock, make a killing, and end up with the casinos. The plan was made possible after Nevada passed the 1969 Corporate Gaming Act, which allowed publicly traded companies to purchase Vegas casinos. (In 1970, Howard Hughes put his Las Vegas growth spurt on permanent hold, as his Mormon Mafia aides secreted him out the Desert Inn's back door to the Bahamas. In a parting shot, Hughes called Bob Maheu "a no-good, dishonest son of a bitch" who "stole me blind."24 Although Hughes's company Summa Corp. maintained the investment, Hughes himself became disinterested in Sin City; in addition to being robbed in the casinos, Hughes had grown weary of battling the federal government's antitrust regulators, tired of battling Kerkorian for Vegas land, and paranoid over the military's continual A-bomb tests in the desert outside the city.)

Thanks to the Gaming Act, corporations seized the baton lustily, moving quickly, as one local historian put it, "to purifying the wages of sin." Overnight, upperworld bastions such as Hilton Hotels, MGM, Holiday Inn, The Ramada Inn Corporation, and impresarios such as Steve Wynn began their irreversible push to give Sin City a superficial veneer not unlike that of Disneyland—but at the heart of it all would remain gambling activities shamelessly rigged in the casino owners' favor.

Thus, to take advantage of the new Gaming Act, Korshak et al. decided they needed to go corporate. As they had done with Moe Morton, the Korshak-Coleman-Levin trio devised a plan that involved partnering with another Chicago to Beverly Hills transplant named Albert Parvin. On the surface, Parvin ran a straitlaced corporation, Parvin-Dohrmann (P-D) Inc., which sold kitchen, hotel, and restaurant supplies and furnishings. P-D even maintained a charitable foundation (The Albert Parvin Foundation) that boasted a current Supreme Court associate justice (and former SEC chairman), William O. Douglas, on its board. The public face of the Parvin charity involved large donations to both UCLA medical research and scholarships to Princeton and UCLA for students from third world countries.25 But other aspects of Parvin drew the interest not only of many in law enforcement, but also of Sid Korshak and others interested in new Supermob business opportunities.

On April 15, 1970, Representative (and future president) Gerald Ford gave an impassioned speech calling for the impeachment of Douglas, in which he described the earliest allegations about the Parvin Foundation and its connections to hoods such as Meyer Lansky partner Bugsy Siegel. "Accounts vary as to whether it was funded with Flamingo Hotel stock," said Ford, "or with a first mortgage on the Flamingo taken under the terms of the sale. At any rate, the foundation was incorporated in New York and Mr. Justice Douglas assisted in setting it up." For his help, Douglas was given a lifetime position on the Parvin Foundation board and by 1968 had been paid over $100,000.*

In fact, Albert Parvin acquired Siegel's Flamingo after Siegel was murdered in 1947, and when he sold it to Morris Lansburgh of Miami Beach in 1960, Meyer Lansky landed a $200,000 finder's fee, and it was assumed Lansky maintained some silent points in the casino.26 Over the years, Albert Parvin had been accused of being a front man for Lansky, having employed Edward Levinson, who had been identified as Lansky's bagman in Las Vegas. 27 After selling the Flamingo in 1960, P-D purchased the Freemont and Aladdin hotels, and it was reported that Parvin's Vegas interests contributed $28,000 per month to the foundation. But there was more.

Still others have described the Parvin Foundation as a "pass-through" for funds of both the CIA and the underworld. Federal courts and Congress have divulged some of these links over the years, including contentions that at least some of Parvin's altruism may have involved setting up third world tax shelters for U.S. hoodlums.28 The company also showed special interest in countries where gambling concessions were up for grabs, such as Cuba and the Dominican Republic. In his speech, Ford noted that in 1963 Parvin began donating educational materials to the regime of the newly installed DR president, Juan Bosch, during a time when he was still mulling over who should be granted that country's casino gambling license. However, when the concession was granted to Nevada's Cliff Jones, Parvin disappeared. "When this happened," Ford said, "the further interest of the Albert Parvin Foundation in the Dominican Republic abruptly ceased. I am told that some of the educational-television equipment already delivered was simply abandoned in its original crates."

In Beverly Hills, former Chicagoan Albert Parvin was well-known to former Chicagoan Sidney Korshak, who later testified to being his friend and fellow Hillcrest member.29 In fact, Korshak had owned stock in P-D since 1962, when it was called the Starrett Corporation. Parvin was also plugged into the Greg Bautzer nexus: Bautzer's partner Harvey Silbert, who operated the Riviera for Korshak, was also on the Parvin Foundation.30 Korshak and Silbert were both directors of Cedars-Sinai Hospital.31

According to testimony, Parvin expressed to Korshak that he was tired of doing business in Vegas and was looking to get out. He was "weary of all the problems in Las Vegas," as one Korshak account put it. Once again, timing played into the fortunes of the Supermob. Since Vegas' recent passage of the Corporate Gaming Act predicted a corporate takeover of the industry, there appeared to be no way for the hoods to compete with Hughes and the rest—their era seemed to have passed. But if they were able to maintain a presence via the indiscreet P-D operation, the cash flow would remain intact.

The Parvin-as-front theory gained traction in July 1968, when LAPD intel reported that Korshak, Dalitz, Dorfman, Lansky's Wallace Groves, and Mrs. Hoffa (standing in for imprisoned Jimmy) had met at La Costa, ostensibly to discuss the sale of the Stardust to P-D. Initially, Dalitz did not want to sell, but it was believed by law enforcement that he was ordered by Meyer Lansky to do so. For the record, Sid Korshak took the credit. In later SEC testimony, Korshak explained, "I told Mr. Dalitz that I thought in view of the fact that he was sick—he had related that to me—he was undergoing a series of tests, there was trouble with a kidney, I believe the other kidney was beginning to become infected too. Mr. Dalitz was past seventy, that he ought to give serious thought to selling the Stardust."32

When Dalitz caved, it would be at least the third time that Korshak took a fee (a whopping $500,000) for helping the Stardust find an owner. Korshak was unabashedly proud of what many believed was an exorbitant fee. "I did an excellent job for the Parvin-Dohrmann Company," Korshak later said. "And my fee was a very inadequate one." He stated he based that assertion on the fact that the total sale price was $45 million.33

Lastly, with Harvey Silbert's help, a deal was also quickly negotiated for P-D to purchase the Riviera. Don Winne, a Justice Department attorney assigned to the Strike Force, expressed the Bureau's fears about Korshak's plan in a 1970 memo that stated, "If allowed to escape unscathed, which so far it has, it will allow the Riviera to be allowed to capitalize their skim on the stock market."34

In later SEC testimony, Korshak put a benign spin on the notorious Las Vegas hotel turnover rate: "There were half a dozen people talking to me at different times about possible acquisitions in Nevada. They would have been companies I was close to, probably represented. There was a period immediately following Mr. Howard Hughes's acquisitions where everybody became interested in making an acquisition in Nevada . . . Every day someone was interested in selling, buying, everybody—if business was good, I guess they would say it is fine; if business was bad, they would say, 'Why do I need it?' If there was an adverse newspaper story, people would say, 'I don't want it. I am going to get out of here. There is an onus on Vegas.' That might change two days later." Korshak also described how he consulted for G&W, Hilton, and Hyatt regarding Vegas acquisitions.35