IN 1971, SIDNEY KORSHAK'S focus quickly turned right back to Washington, where the Nixon White House, as part of Richard Nixon's longstanding ties to the Teamsters, strategized over what to do about Jimmy Hoffa. Apparently, Korshak was among those with a suggestion.

At the time, Nixon was under pressure from many corners to offer executive clemency to Hoffa, imprisoned since 1967 on the jury-tampering and pension-fund kickback convictions. Without presidential intervention, Hoffa was likely to serve out his two concurrent thirteen-year terms; the parole board had rejected Hoffa's parole application three times previously, after expressing concern that Hoffa's wife and son were still on the Teamsters' payroll with salaries totaling nearly $100,000 a year, while Hoffa had received a $1.7 million lump-sum retirement settlement. However, both the rank and file, and the interim Teamster boss, Frank Fitzsimmons, who counted Nixon as a close friend, had been lobbying for Hoffa's release. Other influential constituents such as Ronald Reagan, World War II hero Audie Murphy, and California senator George Murphy all lobbied Nixon on Hoffa's behalf, hoping to obtain either Teamster business or pension-fund financing for pet projects. At the time, Murphy was working for D'Alton Smith, the son-in-law of Korshak associate New Orleans Mafia boss Carlos Marcello. Often Murphy and Smith stayed at Moe Dalitz's Desert Inn while brainstorming the Hoffa issue. On other occasions they met at the same Beverly Rodeo Hotel in Beverly Hills where Korshak negotiated the Schenley labor peace with Chavez's farmworkers.1

In prison, a confident Hoffa told his son, "My association with the mobs has hurt me, no doubt about it. It gave Bobby Kennedy the handle to immobilize me, put me in jail—uproot me from my union work. But I'm coming back."2 Aware of the work of his fellows on the outside, Hoffa felt certain that an early parole was inevitable. Nixon may have been leaning toward such a move, since he felt he owed Hoffa for the million-dollar contribution he had made to Nixon's candidacy in 1960. However, Nixon was finally convinced by the promise of another fat check, this one from none other than the Supermob's underworld partners in Chicago and Las Vegas. According to some, Sidney Korshak was one of the key behind-the-scenes negotiators—understandable given his power in Vegas and his connections to such Nixon intimates as Murray Chotiner and Henry Kissinger.

By early 1971, the Korshak allegations were reverberating across the country. In Washington, F. C. Duke Zeller, who served as communications director, government liaison, and personal adviser to four Teamster presidents, was among those who learned of Korshak's intercession. "I certainly heard that [Korshak] was involved in the negotiating or at least involved in the process," Zeller said recently. "Fitzsimmons had used several people to get to the Nixon White House, and Korshak was one of them. Korshak apparently had intervened on Fitzsimmons's behalf with [Nixon aide Chuck] Colson. I heard about it early on in direct conversations with Fitzsimmons, so there was never any doubt in my mind that Korshak intervened with the Nixon White House to execute that Hoffa deal."3

Also in Washington, an investigator for syndicated columnist Jack Anderson was told of Sidney's broker role by D.C. political-gossip maven Washington Post reporter Maxine Cheshire. "Maxine told Jack Anderson the Hoffa pardon was organized by Korshak using Jill St. John to work Kissinger in order to get to Nixon," said the source, who wished to remain anonymous.

In Chicago, investigator Jack Clarke also picked up evidence of the Sidney connection. "I conned Marshall Korshak into a conversation at Eli's [Steakhouse]," said Clarke. "He told me and a number of other people that his brother Sidney had intervened with the Nixon administration. Hart was involved in that too—the money came from Vegas and Chicago and was being held in one of Hart's banks where the IRS couldn't get to it." Clarke also heard the story from Audie Murphy. "Audie Murphy was my best friend. He told me he was asked by Sidney Korshak to go see Nixon in the White House. Senator George Murphy and Nixon had been good to Audie, and he was told to go to the White House and cop a plea for Hoffa. Korshak talked to Murphy about it in the office of Senator George Murphy, and they got Audie to go talk to Nixon."4

In Las Vegas, where production was ongoing on Diamonds Are Forever, screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz, who saw Korshak often during the shoot, also heard the rumor. "If memory serves me right, it was Sidney who negotiated Hoffa's release with Nixon," Mankiewicz said in 2003. 5

Mob messenger boy/actor/singer Gianni Russo said the Korshak-Hoffa story was known from New York to L.A. "I knew the Korshak talks were going on because there were some messages about it that were going back and forth," Russo recalled recently. "There was a lot of problems coming out of that for a lot of people."6

The main problem was that during Hoffa's absence, both the mob and the Supermob had grown to like Frank Fitzsimmons (and his partner Dorfman) more than Jimmy Hoffa, who only used the mob loans to help strengthen the Teamsters; he was never considered "one of ours" by the hoods. (Hoffa would later become a government informant against Fitzsimmons.) Before going away in 1967, Hoffa had said to his board about Dorfman, "When this man speaks, he speaks for me." He made similar statements about Frank Fitzsimmons. Now the duo surpassed their iconic colleague in his appeasement of the underworld. Under Fitzsimmons and Dorfman, Moe Dalitz was loaned $27 million to expand La Costa; Frank Ragano, Santo Trafficante's lawyer, received $11 million in a Florida real estate deal; Irving Davidson, Carlos Marcello's D.C. lobbyist, received $7 million for a California land purchase; and in addition to Caesars, the fund was tapped to construct the skim-friendly Landmark, Four Queens, Aladdin, Lodestar, Plaza Towers, and Circus Circus.

All told, the pension fund controlled by Allen Dorfman had loaned over $500 million in Nevada, 63 percent of the fund's total assets, and most of it went to the hoods' favored casinos. But, perhaps most important, Fitzsimmons had decentralized Teamster power, which benefited local mob bosses, who could now easily outmuscle small union fiefdoms without having to bargain with an all-powerful president.

Thus all agreed that any Hoffa release would be conditional, mandating that he not assume a political role in the affairs of the Teamsters for at least eight years. According to White House tapes released in 2001, Nixon informed Henry Kissinger on December 8, 1971, "What we're talking about, in the greatest of confidence, is we're going to give Hoffa an amnesty, but we're going to do it for a reason." (Italics added.) Nixon then whispered about "some private things" Fitzsimmons had done for Nixon's cause "that were very helpful." It is now taken as fact that Nixon was referring to another promised "contribution" when the 1972 campaign rolled around.

"It's all set for the Nixon administration to spring Jimmy Hoffa," Walter Sheridan told Clark Mollenhoff. As the man who'd worked closest with Bobby Kennedy in putting Hoffa away, Sheridan was frustrated. "I'm told Murray Chotiner is handling it with the Las Vegas mob."7

It was a busy year for Korshak's good friend (and Richard Nixon's mentor) Murray Chotiner. According to Jeff Morgan and Gene Ayers of the Oakland Tribune, Chotiner was also putting out Teamster fires in Beverly Hills, where a fund borrower had come under indictment for fraud. The affair started with an $11 million 1969 fund loan for a development named Beverly Ridge Estates, a similar undertaking to the misbegotten Trousdale Estates investment in Beverly Hills a decade earlier. In this case the loan went to Leonard Bursten, a Milwaukee attorney who had founded the Miami National Bank, which was used by Lansky and others to launder money and have it transferred to Swiss accounts. Bursten, a political protege of Joe McCarthy's, had also distributed anti-Catholic literature for Nixon's 1960 campaign versus JFK, most likely under the direction of Chotiner. When the Teamsters tried to foreclose on the bankrupt Beverly Ridge partnership, Bursten attempted to conceal $500,000 of the total from the IRS. (When Bursten pled guilty and was sentenced to fifteen years in 1972, the punishment was reduced to probation and the record was expunged after Chotiner supposedly interceded with the U.S. attorney in L.A. who was handling the case.)8

On December 23, 1971, Sheridan's fears were realized, when Nixon in fact granted Hoffa's early parole.* It was later learned that money had been pouring into various Nixon slush funds from Teamster coffers for just that purpose. It was also reported that the money would guarantee that Nixon-Mitchell would take it easy on investigations of pension-fund loans. According to newly released FBI documents, the first payoff came in 1970, via Korshak's underling at the pension fund, Allen Dorfman. The file stated, "Dorfman and another individual (not identified) had a private meeting with [Attorney General] John Mitchell. Dorfman gave $300,000 to Mitchell and obtained a receipt. The money was paid to obtain the release of James R. Hoffa from jail."9

The next big payback came less than a month after five men linked to the White House were nabbed breaking into the Democratic National Committee headquarters housed in the Watergate Complex. The venue itself was riddled with Supermob connections, bizarre coincidences, and laughable ironies:

• The residential portion of the Watergate served as home to the nation's most influential jurist below the Supreme Court—Chief Judge David L. Bazelon of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, friend of both Paul Ziffren and Howard Hughes's enemy Sid Korshak. One year after the break-in, Bazelon would make a critical ruling on the Watergate prosecution, and in 1975 Bazelon and his wife returned home from Christmas vacation to discover their own Watergate break-in: $16,000 worth of jewelry was missing from their apartment.

• The Watergate Complex was owned by none other than Michele Sin-dona's Societa Generate Immobiliare (SGI), and owned in part by the Vatican. SGI, linked to Charlie Bluhdorn's Gulf & Western and Bob Evans's Paramount Pictures, had bought the ten-acre site from Washington Gas for $7 million.

• In what the Washington Post called "a delicious irony for the father of the Watergate," the first Bush administration tapped SGI in 1989 to demolish the new U.S. embassy in Moscow because it was infested with electronic bugs.

• The first known Watergate break-in was a 1969 residential burglary in which jewelry and a papal medal were stolen from the apartment belonging to Nixon's secretary Rosemary Woods, later accused of erasing eighteen and a half minutes of incriminating evidence from one of the president's secret tapes, in which he discussed covering up his own break-in at the Watergate. (Dozens of White House staffers and fully one quarter of the cabinet lived at the complex, including Attorney General John Mitchell, Commerce Secretary Maurice Stans, and Transportation Secretary John Volpe; the residence was nicknamed Administration Arms, and White House West.10

At least one purpose of the June 17, 1972, break-in appeared to have been Nixon's worries over what the Democrats may have sussed out about the payoffs given by Howard Hughes to Vice President Nixon in the fifties and President Nixon in 1968. Nixon had reason to worry: in 1972, at the time of the break-in, the new head of the Democratic National Committee was one Lawrence O'Brien, Hughes's former D.C. lobbyist, who had a good likelihood of knowing about the bribes.

On July 17, 1972, Frank Fitzsimmons and the Teamsters executive board met at La Costa Country Club, and for the first time in its history the Teamsters pledged that its huge membership would support a Republican presidential campaign. It was estimated that more than $250,000 would be collected for the campaign from Teamster officials alone.

Over the coming months, as Nixon became frantic to provide hush money to the burglars, he suggested to aide John Dean (in a conversation being recorded by Nixon), "You could get a million dollars. You could get it in cash. I know where it could be gotten." When Dean observed that money laundering "is the type of thing Mafia people can do," Nixon calmly answered, "Maybe it takes a gang to do that."

Soon thereafter, just as Nixon predicted, over $1 million was funneled to the White House from sources that were the known domain of Sidney Korshak: the Teamsters Pension Fund and Las Vegas. FBI "Hoffa" documents released to the Detroit Free Press in 2002 point out that informants reported:

• Jay Sarno, the owner of Circus Circus, delivered $300,000 to Allen Dorfman at his Chicago home in August of 1972.11

• That same month, Hoffa said "he was aware of certain Las Vegas casino people who had made large cash contributions to the Nixon campaign."

• On January 6, 1973, $500,000 was given to Nixon aide Charles Colson, or a designee, in Las Vegas (Colson later denied this to reporters).12 On that same day, Fitzsimmons retrieved the money from Dorfman's home. Two years earlier, in an internal memo marked SECRET, Colson had reported that "substantial sums of money, perhaps a quarter of a million dollars, available for any . . . purpose we would direct" could be generated by "arranging] to have James Hoffa released from prison." Attorney Colson told D.C. attorney Richard Bergen, "I am going to get the Teamster account in several months."13 In fact, Fitzsimmons later transferred Teamsters legal business to a law firm where Colson would eventually work. Colson, who did prison time for his involvement in the Watergate affair and who now runs a prison ministry, maintained that there was no connection between the commuted Hoffa sentence and the change in Teamsters legal business. Soon after the Teamster money was received by the Nixon camp, John Mitchell indeed scuttled investigations into the Teamsters Pension Fund loans and rescinded the taps on Accardo and friends.

• On February 8, 1973, Fitzsimmons met with numerous California mobsters* near Palm Springs at Indian Wells Country Club (coincidentally the winter home of Chicago boss Tony Accardo) during the Bob Hope Desert Classic golf tournament. The topic of discussion was a new Teamsters prepaid health plan, expected to generate a possible $1 billion in annual business, and real estate transactions in Orange and San Diego counties involving more than $40 million in commercial property—all financed by Teamsters Pension Fund loans.

In the next days, the meetings shifted to Rancho La Costa, where Fitzsimmons met with Chicago's Vegas enforcers Anthony Spilotro and Marshall Caifano, Outfit boss Tony Accardo, and an unnamed Justice Department informant. The motley crew discussed the prepaid health plan, under which a Los Angeles physician named Dr. Bruce Frome would provide West Coast Teamsters with medical care. Monthly medical fees for each member would be paid by the central-states fund from the millions of dollars contributed into it by employers. But most important, it was agreed that 7 percent of take would go to the California underworld, with 3 percent kicked back to a shell company called People's Industrial Consultants, run by the Chicago Outfit. FBI wiretaps revealed that Accardo's underboss Lou Rosanova had set up a Beverly Hills office of People's Industrial Consultants to handle the kickbacks to be paid under the health plan. The office was located at 9777 Wilshire Boulevard, two blocks from Korshak's Riviera office (#9571). The wiretaps at the shell company picked up a conversation between Dr. Frome and Raymond de Derosa, identified by the California authorities as a muscleman for California mafioso Peter Milano, who operated out of the consulting company's offices.14

On the morning of February 13, 1973, Fitzsimmons drove to El Toro Marine Air Station and joined Nixon on board Air Force One for the flight to Washington. According to mob sources located by author William Balsamo, Fitzsimmons told Nixon on the flight, "We're prepared to pay for the request I put on the table. You'll never have to worry about where the next dollar will come from. We're going to give you one million dollars up front, Mr. President, and there'll be more that'll follow to make sure you are never wanting."15 Just days later, the Justice Department shut down the FBI's court-authorized wiretaps.

In May 1973, Korshak's Beverly Hills friend Murray Chotiner publicly took credit for arranging Hoffa's early parole. Chotiner bragged, "I did it, I make no apologies for it, and frankly I'm proud of it!" But when Chotiner was charged by the Manchester Union Leader of April 27, 1973, with also having funneled $875,000 to the Nixon campaign from Teamster officials and Las Vegas gambling interests, Chotiner typically responded with an attack of his own: "Unless there is an immediate retraction, I plan to sue or take whatever action the law allows against whoever is responsible for this horrible libel." Unwilling to take on the expense of a multimillion-dollar lawsuit, the paper retracted the story.

Observing from Chicago, Labor Department organized crime investigator Tom Zander saw what was happening but could do nothing about it. "Anybody who wanted to pay for it had a connection to Nixon," Zander said recently. "The locals gave massive amounts of untraced money to Nixon. They got away with murder." An FBI agent told Los Angeles Times reporters Jack Nelson and Bill Hazlett, "This whole thing of the Teamsters and the mob and the White House is one of the scariest things I've ever seen. It has demoralized the Bureau. We don't know what to expect out of the Justice Department."

Any Korshak participation in the Hoffa-Nixon financial arrangements was juggled with Korshak's own monetary negotiations with the feds. After following up on the SEC's Parvin revelations, the IRS's scrutiny of the sixty-five-year-old Korshak's tax statements resulted in a September 7, 1972, charge that Korshak was guilty of tax evasion and fraud. The agency alleged that between 1963 and 1970 the Fixer had, among other things:

• Only reported $4.4 million of his $5 million taxable income.

• Taken improper deductions for expenses to the tune of $428,056.

• Failed to pay gift taxes on such items as $115,000 in stocks to his sons, and $10,000 to Jill St. John.

Among the details in the charge were the notations that in 1969 Korshak had given each of his sons $20,000 in shares of Al Hart's City National Bank, and that he claimed an average of $16,000 per year in deductions for his Chalon Road mansion, which he claimed as his office. The IRS examiner auditing Korshak's taxes concluded that Korshak's actions were "intentional and substantial." All told, according to the IRS, Korshak owed over $677,000 in back taxes, plus $247,000 in penalties.16

Within months, the IRS turned on Sidney's sixty-three-year-old brother, Marshall, who was at the time the city collector for Chicago, a $23,000a-year job. The feds were focused on the years 1967 through 1970, when Marshall's reported earnings had averaged $155,000 per year, a fraction of his older brother's income, but almost five times his own city pay. The IRS said in a press release that it was interested in Korshak's stock holdings in sixty companies and alleged contributions to an astonishing forty-seven charities.17 Official sources said that the IRS mostly wanted to determine if Korshak was acting as a "nominee" for others in all the stock holdings—a number of local pols, including former governor Otto Kerner (for whom Korshak had served as revenue director), had recently been convicted in a bribery scandal involving horse-racing stocks, and it was believed that illegal investments were now being fronted by nominees. The IRS wanted to see Korshak's brokerage statements to make the case.

Appearing under a summons at the IRS offices on February 6, 1973, Korshak failed to bring his stock records as ordered and instead pleaded immunity under the Fifth Amendment.18 Within days, Marshall traveled to Los Angeles, probably to confer with his big brother.19 Meanwhile, the IRS went to court and obtained an April 18 deadline for Korshak to produce the records. In a headline reading KORSHAK: TALK OR RESIGN, the Sun-Times editorialized that "ethics laws and rules require that public officials be open and aboveboard about their financial affairs . . . If Korshak persists in his refusal to discuss his financial affairs candidly and openly with federal income tax officials, he should resign his public job or be removed by Mayor Daley." 20 A Chicago Today editorial called Korshak's recalcitrance "striking."21

A defiant Korshak appeared for the appointed court show-up empty-handed, again invoking the Fifth. Korshak's attorney, Harvey Silets, contended that the records might incriminate his client, and that the IRS actually wanted the records not for a civil IRS case, but for a possible criminal probe.22 IRS attorney Michael Sheehy told the court that Korshak had admitted the same to him, but that he was most concerned that the records might be used in a criminal case against his brother.23

In August 1973, six months after the IRS probe began, it ended suddenly when word came down from Washington that the agency had in fact been pursuing a criminal investigation, which allowed Korshak to invoke the Fifth and to refuse to deliver his records unless he was charged with a crime.24 The matter of Sidney's taxes was litigated over the next year and was settled just before the case went to trial in 1974, with the IRS dropping all the fraud charges against Korshak and agreeing to allow him to pay only $179,244, 20 percent of the initial demand.

Interestingly, the period was marked by tax problems not only for the Korshaks, but also for Al Capone's former personal attorney Abraham Teitelbaum, the man who'd introduced Sidney to the world of organized crime legal representation and mentored him in the labor-negotiating game. In the years since his recruitment of Korshak, Teitelbaum's star had risen and fallen precipitously. After Capone, Teitelbaum drew a suspicious $125,000per-year salary from the Outfit-controlled Chicago Restaurant Association, represented bosses like Joey "Doves" Aiuppa, and repeatedly pleaded the Fifth Amendment before the McClellan Committee. In the sixties, the IRS hit Teitelbaum with a bill for over half a million in back taxes, forcing him into bankruptcy, and a divorce from his wife.

In December 1972, Teitelbaum was convicted for real estate fraud and sent to serve a one-to-ten-year sentence at California's State Prison in Chino.

In desperation, according to a close family friend, Teitelbaum had him make a call to the protege he had advised for three decades, Sidney Korshak, hoping he would come see Teitelbaum and employ his famous talents as the Fixer and make the conviction just go away. He located his high-flying recruitee, then living in Chalon Road luxury, and made his request. However, the voice on the other end of the phone was cold and dismissive.

"I won't go anywhere near that place," Korshak said. "I wouldn't go visit him. I won't help him, and as far as I'm concerned, his days are over. I don't want anything to do with Abe Teitelbaum."25

It is not known what turned Korshak against Teitelbaum, although it might be assumed that he was still bristling over Teitelbaum's $50,000 fee in Vegas in 1964. Also, Teitelbaum had famously had a falling-out with Korshak's great friend Chicago boss Tony Accardo, in 1953, prompting two Accardo enforcers to threaten to push Teitelbaum out of his office window.26 After his brief prison stint, Teitelbaum stayed in California, where he lived in the $2.50-per-night Burton Way Hotel, sharing a kitchen with twenty other forlorn men. Teitelbaum died in 1980. 27

Making Movies with Charlie, Bobby, Cubby — and Sidney

The advent of 1971 saw Sid Korshak navigating the safer waters of his labor consultancy forte. At the time, Paramount's production chief, Robert Evans, was attempting to package a film project based on Mario Puzo's wildly successful novel The Godfather, for which Evans owned the movie rights. Three years earlier, as Evans tells it, he gave Puzo $12,500 to pay off gambling debts in exchange for a then unpublished 150-page manuscript entitled The Mafia. When Puzo's retitled book The Godfather took off, Paramount began assembling the film version in earnest. However, the director, Coppola, was part of the new breed of film auteurs who were keen on creating paradigms at odds with executives such as Bob Evans, who were tied to the old traditions. As "New Hollywood" chronicler Peter Biskind aptly put it, "The casting of The Godfather was a battle between the Old Hollywood approach of Evans and the new Hollywood ideas of Coppola."28

When considering the key role of Mafia scion Michael Corleone, Coppola's first choice was a young Bobby De Niro, who tested beautifully, but was considered too much of an unknown by the suits. The director's second choice was a diminutive young New York actor named Al Pacino, but this selection was also greeted with disapprobation, especially by Evans, who referred to Pacino as "that little dwarf." Like De Niro, Pacino tested well for the part, but Evans wouldn't accept him; Evans wanted the film to be anchored by a studio stalwart such as Warren Beatty or Jack Nicholson. However, when Coppola went on a European vacation, Pacino's The Panic in Needle Park opened and immediately convinced Evans that Coppola was right about the young thespian. But by the time Evans warmed up to Pacino, the actor had already signed with MGM to film The Gang That Couldn't Shoot Straight.29 And MGM's new owner, a Bluhdorn-like wheeler-dealer named Kirk Kerkorian, was not about to sell him to the competition.

The Avis of Vegas

Kerkor "Kirk" Kerkorian was born on June 6, 1917, in Fresno, California, the son of an Armenian grocer. Like Howard Hughes, Kerkorian became enamored of aviation, creating a charter flight service that carried gamblers like himself to Las Vegas. A stock swap with the Studebaker car company was the initial link in a chain of events that included Kerkorian's buying back the company and taking it public. The business would develop into Trans International Airlines (TIA), the object of Kerkorian's first great financial triumph. A former high-stakes gambler (said to have bet $50,000 at a craps table in one night), Kerkorian also shared Hughes's reputation as a womanizer, later being linked with actresses Priscilla Presley and Yvette Mimieux before his divorce from his second wife, Jean, and with Cary Grant's widow, Barbara, in the years since.

Much like Wasserman, Kerkorian was more interested in power accumulation than the actual business itself. As Richard Lacayo wrote in Time, "For him it has always been the deal, not the business . . . Deal making seems to satisfy the gambler in Kerkorian, a man more at home in Las Vegas than in Hollywood."

Kerkorian, however, was not without his own associations with underworld denizens, especially after a 1961 New York wiretap implied that he was making payments to the mob. A 1970 investigation in New York State revealed the nine-year-old recording of Kerkorian promising to send a $21,300 check to Charlie "the Blade" Tourine—a known enforcer for the Genovese crime family. When Tourine called Kerkorian, he used the code phrase "George Raft is calling." On this occasion, Kerkorian told Tourine that he (Kerkorian) would write a check to himself, endorse it, and have it sent to "George Raft" at New York's Warwick Hotel. Kerkorian said he did the payment this way so as to avoid Tourine's endorsement signature on the back, since, as Kerkorian said, "The heat was on."30

The same year that The Godfather went into production (1971), New York businessman Harold Roth testified before the New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Crime that Tourine had introduced Kerkorian to Roth twelve years earlier, with Tourine calling Kerkorian "a very good friend of mine." At the time, Tourine was hoping to have Roth help finance Kerkorian's purchase of an $8 million DC-8 jet. Kerkorian later told a friend that he indeed knew Tourine, whom he referred to as Charlie White. Kerkorian explained that he was simply paying a gambling debt and was not involved in organized crime. A 1971 Forbes interview, in which Kerkorian asserted his innocence, was his last press interview to date.

In 1969, Kerkorian sold his TIA stock for more than $100 million and, as per his custom, reinvested the profit right into his next brainstorm—Las Vegas. Thanks to the same Corporate Gaming Act of 1969 that gave other publicly traded companies a Vegas foothold, Kerkorian announced that he would be opening what was then the largest hotel in the world (1,512 rooms), the International (now the Las Vegas Hilton), on Paradise Road. Kerkorian had already purchased the Flamingo in 1967 as a training ground for the new colossus, from a group that included Meyer Lansky. At the same time, Kerkorian asked Korshak pal Greg Bautzer to call MGM to discuss a possible sale of the studio. In this pre-Godfather, preblockbuster era, big studios were in decline. Some say Easy Rider, which was shot for $300,000 and grossed $30 million, started the trend toward less expensive "youth market" movies. Kerkorian believed it to be a cycle that would reverse, and the time was right to buy cheap. A year later, Hughes asked Bautzer to do the same for him.

The International was less than a spectacular success, and mounting debts forced Kerkorian to sell controlling interest to Hilton Hotels with the proviso he would not build a competing hotel in Las Vegas. All the while, Kerkorian was buying huge blocks of stock in troubled MGM, and by 1971 he had succeeded where Korshak partner Phil Levin had failed and now controlled MGM. And he had one more big announcement: he would—again—build the world's largest resort hotel (2,084 rooms), again on Paradise Road in Las Vegas. This time, he would have to do it behind the corporate veil of MGM in order to comply with his Hilton contract.

Kerkorian thought to use the association with the MGM film Grand Hotel to construct the new hotel, which assumed the name The MGM Grand. Kerkorian purchased the land from Realty Holdings, which was controlled by Merv Adelson, Irwin Molasky, and Korshak's great friend Moe Dalitz. "I don't see anything wrong with buying a piece of vacant property from these people," Kerkorian said. "What's wrong with Moe?"31

Such was the setting when Paramount asked MGM to sell its Pacino contract to them, allowing the actor to become "Michael Corleone." Evans first called MGM's president, Jim Aubrey, who had been introduced to owner Kerkorian by the ever-present Greg Bautzer. "With the emotion of an IRS investigator," Evans wrote in his autobiography, "he turned me down." The way Bob Evans saw it, he had no choice but to call his consigliere, Sidney Korshak.32

As recounted in his memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture, Evans, who was in New York at the time, placed a call to Korshak at his New York "office" "I need your help." in the Carlyle Hotel.

"Yeah?"

"There's an actor I want for the lead in The Godfather."

"Yeah?"

"I can't get him."

"Yeah?"

"If I lose him, Coppola's gonna have my ass."

"Yeah?"

Evans advised Korshak of his out-of-hand rejection by MGM's Aubrey, a revelation that elicited a nonstop recitation of "Yeah"s from Korshak.

"Is there anything you can do about it?"

"Yeah."

"Really?"

"The actor, what's his name?"

"Pacino . . . Al Pacino."

"Who?"

"Al Pacino."

"Hold it, will ya? Let me get a pencil. Spell it."

"Capital A, little /—that's his first name. Capital F, little a, c-i-n-o"

"Who the fuck is he?"

"Don't rub it in, will ya, Sidney. That's who the motherfucker wants."

As Evans tells it, twenty minutes after his call to Korshak, an enraged Jim Aubrey called Evans.

"You no-good motherfucker, cocksucker. I'll get you for this," Aubrey screamed.

"What are you talking about?"

"You know fuckin' well what I'm talking about."

"Honestly, I don't."

"The midget's yours; you got him."

That was Aubrey's final statement before slamming the phone down on a befuddled Evans, who immediately called his mentor Korshak. The Fixer advised the producer that he had merely placed a call to Aubrey's boss, Kirk Kerkorian, and made the request. When Kerkorian balked, Korshak introduced his Teamster connections into the negotiations.

"Oh, I asked him if he wanted to finish building his hotel," Korshak told Evans.

"He didn't answer . . . He never heard of the schmuck either. He got a pencil, asked me to spell it—'Capital A, punk /, capital P, punk a, c-i-n-o.' Then he says, 'Who the fuck is he?' 'How the fuck do I know? All I know, Bobby wants him.'"

Interestingly, after Pacino was released from the MGM picture, his replacement was Bobby De Niro, who had previously tested so well for Pacino's Michael Corleone role.

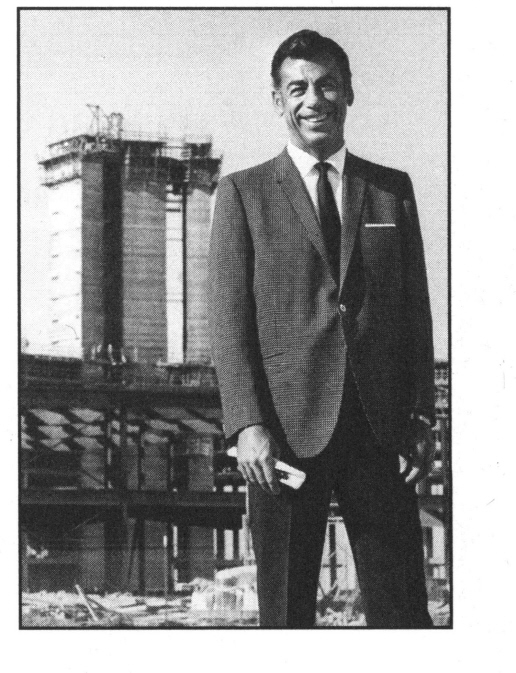

Kirk Kerkorian stands in front of his under-construction Vegas hotel, the International, 1969 (UNLV Special Collections)

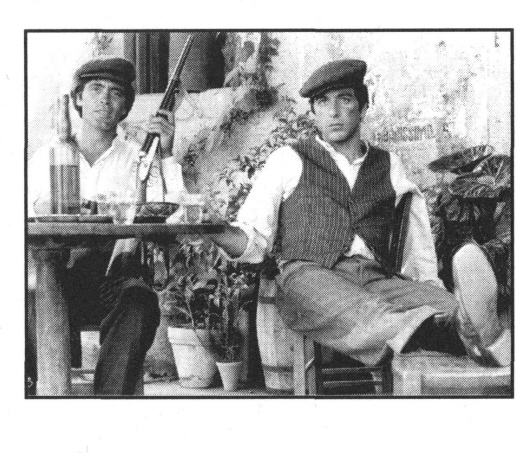

Al Pacino in The Godfather (Photofest)

On April 15, 1972, Kerkorian broke ground for the MGM Grand (now Caesars Entertainment's Bally's) and opened the hotel on December 5,1973, earning him the moniker Father of the Mega-Resort. The movie-nostalgia-based hotel boasted a twenty-five-floor tower with "walls of glass," and Rhett Butler and Lara suites. For the grand opening, Korshak friend Dean Martin appeared in the Celebrity Lounge. Many viewed with suspicion the fact that the hotel was completed just one day before a new code came into effect that would have mandated fire-suppression sprinklers be installed. Seven years later, eighty-seven MGM Grand guests and employees were killed and hundreds injured in a horrific fire that would likely have been minimized by the sprinklers. The tragedy is still referred to as the worst disaster in Las Vegas history.

Although Kerkorian has typically been seen as second to Howard Hughes in the Vegas mogul sweepstakes, the reverse was true. "He's the second deep pocket who brought legitimate capital to town. [But] he's also the first person to come here and build as a hands-on operator," University of Nevada, Las Vegas, History Department chairman Hal Rothman said. "Howard Hughes doesn't count because he didn't build." Rothman added that Kerkorian is no longer "the Avis of Vegas." Casino expert Bill Thompson pointed out that Hughes did not bring in the massive capital infusions that were ultimately successful in squeezing out the mob: "Kerkorian rescued us from Hughes. By making properties so big, he took them out of the reach of the Mafia. They were too big and too expensive."*

As The Godfather proceeded into production with Pacino and the rest of the cast now assembled, Evans et al. faced their next hurdle, this time with antagonists even more intransigent than Kerkorian: the Italian Anti-Defamation League and the Mafia. Mario Puzo had already warned Coppola, "Francis, when you work on this, the real Mafia guys are gonna come. Don't let them in."33 Coppola knew what Puzo was saying. "I remember when I was a kid—they're like vampires," Coppola said. "Once you invite them over the door, then you're theirs."

As expected, the production felt the backlash, first in Los Angeles, where the famous Paramount gates were blown off their hinges by pro-Italian protesters. On their New York set, the moviemakers were stopped before they could start, while Evans received anonymous phone calls at his Sherry Netherland suite in which his son Josh's life was threatened. The voice on the other end warned, "If you want your son to live longer than two weeks, get out of town." The thought of his newborn son, Josh (with actress Ali MacGraw), being killed prompted another Evans call to Korshak for rescue.

According to Evans, what opened up New York "like a World's Fair" was a phone call to the Mafia from Korshak. Suddenly, according to Bob Evans, everyone cooperated, "the garbagemen, the longshoremen, the Teamsters." New security people even showed up. Evans later wrote, "One call from Korshak, suddenly, threats turned into smiles and doors, once closed, opened with an embrace." In a 1997 interview Evans concluded, "The Godfather would not have been made without Korshak. He saved Pacino, the locations, and, possibly, my son."34 Producer Al Ruddy remembered that Evans still couldn't relax. "Evans hid out on the whole fuckin' movie," Ruddy said. "He went to Bermuda with Ali."

A lawyer friend of Korshak's who had been referred a number of hoodlum clients by Korshak told Los Angeles DA investigator Jim Grodin that Korshak was well compensated for his efforts, supposedly receiving a piece of the movie's gross profits.*

But even Korshak could not predict that an upstart mafioso would exert his own Godfather-type power play in a bid to start a sixth New York crime family. Production assistant Dean Tavoularis has spoken of how the Italian Anti-Defamation League, which was run by mafioso Joe Colombo of the Profaci crime family, had his unions and supporters shut down the production in New York. The traditional five families were already disturbed by Colombo's affiliation with the League and his love affair with the press, a cardinal sin in the eyes of the traditional Mustache Petes. The problem's resolution came from an unlikely source.

At the time, Las Vegas singer and occasional Mafia messenger boy Gianni Russo was desperate to get a major role in the movie and had auditioned in vain weeks earlier. When he heard about the Paramount gate destruction and the intrusion by Colombo, Russo, a Brooklyn native and now a captain of the Italian Anti-Defamation League in Vegas, saw his golden opportunity. He took the first plane to New York and went directly to the Gulf & Western building, somehow finagling a meeting with Bluhdorn and producer Al Ruddy. He convinced Bluhdorn that he had influence with Colombo and would broker a peace if he was given a plum role in the movie. The trouble was, Russo had never even met Colombo, but he knew his son and some of his underlings.

With Bluhdorn's blessing, Russo visited Colombo in his Brooklyn office and convinced him to meet with Bluhdorn and the rest, where he could demand some script changes and Defamation League black-tie fund-raisers at every local premiere of the movie. "He bought the idea and loved it," Russo said. All Russo wanted in return was one of three coveted roles in the movie: Corleone's sons Michael or Sonny, or the wayward son-in-law, Carlo. Again, Colombo agreed.

The next morning, Russo, Colombo, and his entourage sat across the table from the G&W suits on the thirty-third floor of the Gulf building. Also there were the film's producers Al Ruddy, Gray Frederickson, Fred Roos, and their lawyers. "They were as white as ghosts," Russo said of the executives. "They did not know what they were about to hear or if they were all gonna get thrown out a window."35

In short time, it was agreed that Colombo could see the script, and he turned to an underling and said, "Butter, read it." After some give-and-take, the producers agreed to remove all anti-Italian references, such as Mafia (the term never appears in the movie). They also agreed to the black-tie events, but, as the group started to rise and shake hands, Russo worried about his reward for brokering the deal. "I leaned over to Joe Sr.," recalled Russo, "and I say, 'What about me?' "

With that, Colombo raised his hands, and everyone sat back down like puppets on a string. "What about my boy here? What are we gonna do for him?" the boss asked. The producers said that the first two roles were spoken for, but they had not yet gotten to the part of Carlo, Don Corleone's son-in-law.

You're gonna get to Carlo right now," Russo ordered.

"Oh, yes, please," added Colombo. "Gianni is playing Carlo."

No one present was about to argue, and Russo got the part. However, when filming commenced, Marlon Brando, playing the lead role of patriarch Don Corleone, informed Coppola that he would not perform with the unknown Russo. When Russo heard, he put his arm around Brando and walked him to a back room, where they could speak privately—"because I didn't want to embarrass the guy in front of the other actors," Russo later said.

"Let me tell you something, okay?" Russo told the acting icon. "This is my fucking break in life and you or nobody else is gonna fuck it up. Do you understand what I'm tellin' you? I don't give a fuck who you are, I'm staying in this fucking movie." To which Brando responded meekly, "That was brilliant, great acting." As Russo wrote in his autobiography, "That was the end of the story."36

Russo was not the only "connected" person to appear in the movie. "All the extras in the wedding scene were Colombo hoods," producer Gray Frederickson recently said.37 Predictably, some of the actors were infatuated by the hoods—but not Coppola, who remarked, "I never wanted to know them. I never started hanging out with the big one, like Jimmy Caan." When asked who "the big one" was, Coppola said he believed it was Carmine Persico. 38 G&W reneged on the black-tie events after Colombo was shot on the league's dais during a June 28, 1971, rally, soon after the New York filming wrapped. (The assassination attempt, which ironically occurred right in front of the G&W building, left Colombo in a vegetative state until his death on May 23, 1978.)

When the film was screened for a party of Hollywood insiders at a Malibu estate, television icon and antimob crusader Steve Allen somehow made the guest list. "There was the usual crowd there," Allen said in 1997, "but there were also a few swarthy Vegas boys who had 'organized crime' written all over them. After the movie, my wife Jayne made a remark about gangsters that caused one producer, who was friendly with the mob, to get in her face. 'You have no idea what you're talking about, lady,' this character told her." Allen said he intervened before the face-off got ugly, and soon thereafter, he and Jayne made their exit.

"The next morning, while I'm just waking up," Allen said, "our housekeeper came banging on our bedroom door."

"Mr. Allen! Mr. Allen!" called the frantic woman. The entertainer rushed out and followed his housekeeper to the front porch, where, in a scene reminiscent of the movie he had just seen, he found an enormous severed leg and shoulder of a horse. Allen knew the name of the producer who had the set-to with Jayne and, in a show of defiance, had the carcass delivered to his home. (The producer, whom Allen identified to this writer, was a close friend of Johnny Rosselli's, who Allen believed also attended the screening.)39

On March 14, 1972, the night before the gala New York premiere of The Godfather, Bob Evans put out still another fire for his precious film; this time the quixotic star, Marlon Brando, had decided to skip his own premiere. A frantic Evans reached his good friend Dr. Henry Kissinger, who was dealing not only with a Washington snowstorm, but a setback at the Paris Peace Talks with the North Vietnamese, who were threatening to walk out. Incredibly, Evans convinced Kissinger to come to New York and stand in for Brando. When Evans informed Korshak, in town with Bernice for the event, the Fixer was not impressed.

"You sure it's all right?" Korshak asked. When Evans asked why there might be a problem, Korshak explained, "It ain't no ordinary film. That's why. It's about the boys—the organization. It's a hot ticket." When Evans demanded to know exactly what the problem was, Korshak said tersely, "Nothing and everything."

At the postpremiere party at the St. Regis Hotel, Evans strolled over to Sidney and Bee's table and told Bee, "Without the big man, none of this could have happened. Join our table, will you?" An unsmiling Korshak said, "No." When Evans again demanded an explanation, Korshak's fuse was lit.

"And give the press a fuckin' field day?" Korshak asked.

"Come on, Sidney, it's your night too," Evans persisted.

At that, Korshak grabbed Evans's arm "like a vise" and fixed him with "the Look" he had mastered forty years earlier on the mean streets of the Outfit's West Chicago domain. "Don't ever bring me and Kissinger together in public. Ever! Now go back to your table, spend some time with your wife, schmuck."40

The Godfather netted $86.2 million in its first run domestically, going a long way toward both reinvigorating Paramount Pictures and justifying Evans's hiring to the disbelievers. Francis Ford Coppola quickly used his new clout (and his profit share of the movie as collateral) to secure a $700,000 loan from Al Hart's City National Bank of Beverly Hills so that he could help finance the film American Graffiti for his friend director George Lucas. However, before he actually took the money, Sid Korshak talked Coppola out of it, explaining that if Graffiti flopped, Coppola's children would suffer by losing their future royalties from The Godfather.41

coppola's profits, however, are far less interesting, and less ironic, than those of the Sicilian industrialist who had been brought into the Paramount ownership structure two years earlier. It will never be known how much profit was funneled by Michele Sindona from the iconic Mafia movie to the real Mafia, but it is a certainty that some was. However, Sindona's star had reached its apogee and was soon to start a steep descent into eventual burnout. It was a complicated drama, with the following highlights:

• In 1972, Sindona bought a 21 percent interest in New York's Franklin National Bank, which collapsed two years later, leading to Sindona's conviction for massive bank fraud and to a chain reaction in Italy that saw Immobiliare stocks crash and the Vatican Bank, or IOR (Istituto per le Opere di Religione), which Sindona had tied to Immobiliare, lose $30 million. In addition, much of the $1.3 billion invested in the Bahamian shell companies simply vanished when the IOR stock collapsed. The IOR eventually acknowledged "moral involvement" with Sindona and Calvi and was forced to pay back $241 million to the creditors involved with Banco Ambrosiano.

• In 1974, after Sindona was indicted in Milan for bank fraud, he retained the law firm of Nixon's former attorney general John Mitchell to represent him in fighting the extradition from the United States. However, he was found guilty in absentia on twenty-three counts of misappropriating funds and sentenced to three and a half years in prison.

• On August 6, 1978, Pope Paul VI died after fifteen years in the papacy.

Three weeks later Pope John Paul I assumed the papal throne. On September 28, Cardinal Jean Villot, the former Vatican secretary of state, was asked to stay on temporarily and begin an investigation into the financial dealings of the IOR. Later that night the pope was found dead, allegedly due to natural causes. He had been pope for only thirty-three days.

• On July 11, 1979, Italian magistrate Giorgio Ambrosoli, who had been compiling evidence against Sindona for five years, was shot to death, as were two other prosecutors. Enrico Cuccia, an Italian banker who had met with Sindona in New York three months earlier, testified that Sindona had told him that "he wanted everyone who had done him harm killed, in particular Giorgio Ambrosoli."

• In February 1980, Sindona went to trial on charges stemming from the collapse of the Franklin National Bank. Soon after, on March 27, 1980, he was found guilty of sixty-five counts, including fraud, conspiracy, perjury, false bank statements, and misappropriations of bank funds, and sentenced to three twenty-five-year terms and one twenty-four-year term.

• The Vatican bank scandal was effectively swept under the carpet in 1982. However, in Sicily, Sindona and sixty-five mafiosi were indicted for smuggling $600 million worth of heroin a year.

• On March 18, 1986, Sindona was sentenced in Milan to life for the murder of Ambrosoli. Two days later he died of cyanide poisoning—a favorite Mafia method to silence prisoners who know too much.42

Eighteen years after The Godfather premiered, The Godfather Part HI was released, which drew heavily on the actual history of the Sindona-Immobiliare-Vatican bank scandals and the cross-pollination of the Sicilian and New York Mafias. It went so far as to use the name Immobiliare and to suggest that the pope had been murdered because of his intent to clean house. The film's closing credits include the following: "Dedicated to Charlie Bluhdorn, who inspired it."*

Before 1972 ended, Charlie Bluhdorn had still one more face-off with the Mafia. At the time, Italian producer Dino DeLaurentiis had just completed filming The Valachi Papers, about the infamous Mafia turncoat Joseph Valachi. According to DeLaurentiis's assistant to the producer, Fred Sidewater, the film was another that proceeded only with the sage counsel of Sid Korshak:

We had three production assistants working as drivers who were really the greatest gofers around, and they were running around the lots and using their cars to run errands. Well, I got into the office and was told the Teamsters were shutting down the studio because we were using non-Teamster-affiliated drivers.

I said, "Korshak can help," and I asked him and he said, "Don't let those kids drive anymore," and I said I couldn't join the Teamsters 'cause it would have changed my independent position and I'd get in trouble with all the other guilds. So finally he told me to go meet these three Teamster guys in Culver City Park and stand near a phone booth and talk to the guys standing next to it and answer the phone when it rings. I did what he said, and I told them that we weren't taking business away from them and that we couldn't afford to pay for a driver. Then the phone rang and it was Sidney. "Let me speak to one of the guys," he said—I think it was Andy Anderson. Anyway, I spoke to the guy after he got off the phone and he said, "Look, just don't let them do anything that Teamsters guys would be doing."43

Hoping to corner the market on mob cinema, Paramount was set to distribute The Valachi Papers—Paramount had distributed DeLaurentiis's films since 1955. However, at the last moment, Bluhdorn called the producer in a panic and pulled out of the deal after the Mafia had threatened to bomb the Gulf & Western building if he proceeded. DeLaurentiis then took the film to Warner Brothers, which was interested, but begged off after hearing of the threat to Bluhdorn. To save the film, DeLaurentiis went to Miami and met with Meyer Lansky's right-hand man, Vincent "Jimmy Blue Eyes" Alo, who promised to have the mob back off if DeLaurentiis would set one of Alo's Mafia friends up in Hollywood, which DeLaurentiis readily admitted he did.* From that point on, DeLaurentiis was dogged by rumors of his own Mafia connections, stories that alleged that he laundered mob money to finance his extravagant foreign-financed films.44 Fuel for that fire also came from the fact that DeLaurentiis was a longtime friend of Michele Sindona's, who had personally approved a $1 million loan from his Franklin Bank for DeLaurentiis's move to New York and into his new offices on the fiftieth floor of Bluhdorn's Gulf & Western building.45

The King of Cool Meets the Fixer

Helping his ward Evans with The Godfather production was but the first of two favors that the Fixer performed for the young Paramount chief that year. However, the second series of intercessions had little to do with business, and much to do with Bob Evans's third sinking marriage.

While wrapping The Godfather in early 1972, forty-one-year-old Evans was weakly attempting to navigate the stormy waters of marriage number three, this one to actress/model Ali MacGraw, eight years his junior. After marrying the beautiful former Wellesley art history major in 1969, Evans cast her in the blockbuster Paramount film Love Story. But MacGraw, now the hottest young actress in America, was soon to learn that Evans's workaholic lifestyle was not the stuff of a good marriage. (Evans spent one night in January 1971 in Hollywood meeting with Coppola instead of with Ali in New York when she gave birth to their son Joshua.46 In 1972, when Ali picked up a serious case of adult mumps while the two were in Europe, Evans flew back to the United States to put out more fires on The Godfather, leaving her with a strange French doctor in Antibes.)

In early 1972, Evans strongly suggested that Ali costar with macho actor Steve "the King of Cool" McQueen in a movie to be entitled The Getaway. Ali, who had met McQueen briefly once before, resisted—the sexual tension between the two was an affair waiting to happen. Ali later said that after the first meeting, "I had to leave the room to compose myself. He walked into my life as Mr. Humble, no ego, one of the guys. Steve was this very original, principled guy who didn't seem to be part of the system, and I loved that. He was clever, demure, exciting, and had all the answers. I bought that act in the first second. We had this electrifying, obsessive attraction." Ali knew that if she accepted the role, she and McQueen would become lovers, and her floundering marriage to Evans would be over.47

But Evans prevailed, MacGraw moved to El Paso to start the picture, and the sparks between the two actors flew immediately. According to Paramount's distribution chief Frank Yablans, Evans intentionally torpedoed the marriage. "Evans pushed them together," Yablans said. "He didn't give a shit. It didn't matter to him. He's a very strange man. He couldn't be married, couldn't live a normal, sane life. He drove her out."48

By July 1972, as the Evans-MacGraw union was crumbling, Henry Kissinger offered to go to Texas for Evans to attempt to broker a peace between the two sides—hopefully with more success that he was seeing in his efforts with the warring Vietnamese factions. However, Evans declined the offer, citing Kissinger's more pressing concerns.49 Eventually, Sid Korshak was brought into the fray for the first of many Evans-MacGraw minidramas. The occasion was a marital breakdown at one of Evans's and Korshak's favorite getaways, The Hotel Du Cap on the French Riviera. For this impasse, Evans called Sidney in Bel-Air, and his friend hopped a jet for the six-thousand-mile marriage-counseling trip. "On to the rock flew Sidney Korshak," Evans wrote, "my consigliere, for one purpose and one purpose only—to keep my rocky marriage from falling into the sea. Each day Sidney would sit with Ali for hours, trying to persuade her to make the marriage work." Korshak's attempt at damage control temporarily forestalled the inevitable. 50

When Evans learned of the MacGraw-McQueen affair, he again called on Korshak. According to Bistro owner Kurt Niklas, who overheard the conversation, Evans met with his mentor in the restaurant's private room upstairs and informed him that he wanted his rival McQueen murdered.

"Just calm down, Bobby," Korshak said. Over the next few minutes, Korshak succeeded in cooling off Evans, who left the restaurant. "He hadn't been gone ten minutes," Niklas wrote, "when McQueen arrived, asking for Korshak." Now, not only Niklas but the entire wait staff strained to eavesdrop on the confab. According to one good source, McQueen had met Korshak years earlier, an occasion that supposedly left McQueen shaken. In a recent interview, the source related, "It was at a New York post-movie-premiere party for one of McQueen's movies. Korshak happened to be there as well. McQueen was drunk—he was known to have a 'short guy' chip on his shoulder. Anyway, Korshak turns from the bar and spills McQueen's drink. So McQueen winds up to punch Sidney, who he didn't know, and Sidney puts up one finger and says, 'Wait, you may be a big star, but if you lay one finger on me, I will have your fucking eyes ripped out.' McQueen either was told or realized who Sidney was and left his own premiere party."

Perhaps with this memory in mind, an obsequious McQueen, known far and wide as a macho figure, appeared before Korshak at his Bistro lair.

"Mr. Korshak, please—I don't want any problems, but he's threatening to kill me," McQueen implored.

"Nobody's gonna get killed, unless things keep going sour," Korshak assured him.

"But I'm talking about my life!" persisted McQueen.

"Just shut up and listen to me," Korshak demanded. Then the two began speaking in hushed tones that Niklas et al. were unable to divine. Finally, Korshak spoke up:

"You do as I say, and nobody's gonna get hurt."

A "sheepish" McQueen then left, only to continue the affair with MacGraw soon thereafter.51

MacGraw moved in with McQueen, and after marrying him in 1973, sought to obtain custody of her son with Evans, Joshua. Evans relented on that, but drew the line when the new couple informed him that they were legally changing the toddler's name to Josh McQueen. McQueen sealed his fate when he had the temerity to call up Evans and criticize the sybarite's

lifestyle.

"Your butler's a homosexual," said McQueen. "Your surroundings, the way you live, is not the environment that's right for Joshua . . . I intend to change his name to McQueen . . . have full control." Of course, McQueen had a good point; Evans was well-known to engulf Woodland in hedonism of all sorts. Lastly, McQueen added, his attorney was drawing up custody papers.

"Good. Take your best shot, motherfucker," railed Evans. "One of us, pal, only one of us is going to come out in one piece."

Slamming down the phone, Evans called his go-to man, Father Sidney, who offered the solution. At Korshak's direction, Evans hired a particular attorney, who, within two weeks, compiled a dossier on McQueen that, according to Evans, was almost one foot thick. When the file was shown to McQueen and his attorney, they crumbled. Not only was McQueen prevented from renaming the child, he was forced to eat more crow when he agreed to only refer to Joshua's father as "Mister Evans.""'52

A final post-Godfather favor for Evans was not quite as successful. When his contract with Paramount was up for renegotiation, Evans told Korshak that, since he had elevated Paramount from ninth to first in studio profits, he felt he should make mogul money.

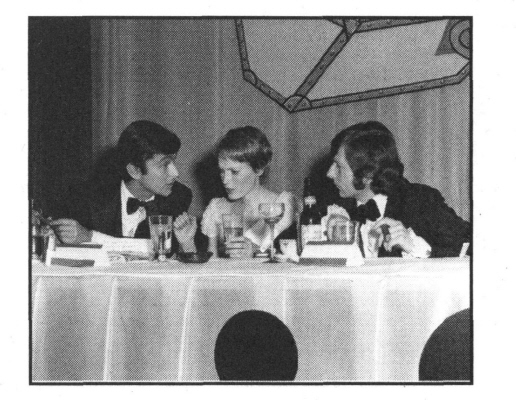

Bob Evans (left) with Mia Farrow and Roman Polanski, 1968 (Photofest)

"I'll take care of it and quick," Korshak told Evans. "You're gonna get gross." Bluhdorn, however, would hear none of it. The best Korshak could obtain for Evans was a one-film-per-year independent production deal that would see him share any profits fifty-fifty with Paramount. Evans took the deal and formed Robert Evans Productions, but later lamented, "Korshak was a negotiator, not an entertainment attorney."53

Evans went on to produce a number of successful films, such as Marathon Man (1976) and Urban Cowboy (1980). But perhaps his greatest post-Godfather triumph was a film laden with Supermob irony, Chinatown (1974). Directed by a brilliant Polish pederast named Roman Polanski, the same man who helmed Paramount's Rosemary's Baby, the film thinly fictionalizes William Mulholland's "Rape of Owens Valley" (see chapter 4). Since the savage murder of Polanski's pregnant actress wife Sharon Tate and four of her jet-set pals by Charles Manson's "family" on August 9, 1969, Polanski had begun indulging his predilection for having sex with children, thirteen- to fifteen-year-old girls preferably, as a way to assuage his grief. * The sickness would eventually bring him before Korshak's great friend Judge Laurence Rittenband. In the film Chinatown, which also included a Polanski nod to sexual perversion, the character Hollis Mulwray subbed for William Mulholland. It is not known if Evans was aware of the similarities between the California land and water grabs of Mulholland/Mulwray and those of Korshak's Supermob associates Greenberg/Ziffren/Bazelon.

Chinatown marked the high point of Evans's career, which was soon to succumb to a cocaine-fueled hedonism that was extreme even by Hollywood standards.

The Man with the Golden Touch

Korshak's casting prowess was again evidenced in the spring of 1971—just one month after The Godfather went into production—when Korshak's

great friend producer Cubby Broccoli was casting a new film, and Korshak had an idea as to who should get the lead.

Albert Romolo "Cubby" Broccoli was born in 1909, the son of immigrants from Calabria, Italy. The Broccolis were in the vegetable business, with one of Cubby's uncles actually having brought the first broccoli seeds into the United States in the 1870s. In 1933, after years of toiling in the vegetable business, Cubby visited his cousin (and ex-husband of blond movie goddess Thelma Todd) Pat DeCicco, a Hollywood agent and starlet gofer for Howard Hughes, and decided to get into the movie business.'1" "Pat had brass balls and was very charming," said friend Tom Mankiewicz, screenwriting son of director Joseph Mankiewicz. "He'd take guests to Hughes's island in the Bahamas—the island would always be filled with Pat and his people."54 Coincidentally, on his first flight to L.A., Broccoli sat next to Korshak pal Jake "the Barber"

Factor.55 After working on the Howard Hughes film The Outlaw (and becoming close to Hughes), Broccoli moved to England, where he entered into a producing partnership with Harry Saltzman, and in the late 1950s they bought the screen rights to the James Bond novels of MCA client Ian Fleming, producing the first Bond movie, Dr. No, for $1 million in 1962.i"'56

In the interim, Broccoli relocated to Beverly Hills, where he nourished his friendships with Sid Korshak, Lew Wasserman, Greg Bautzer, Mike Romanoff, and others in their circle.

"Cubby Broccoli and Sidney were like brothers," said a Korshak family friend. "They had lunch together at the Bistro all the time."57 Tom Mankiewicz recently said, "Cubby and Sidney's relationship was amazing."

In early 1971, Broccoli was prepping the seventh film in his Bond franchise, Diamonds Are Forever, a roman a clef parody of his friend Howard Hughes. By this time, Hughes was a debilitated billionaire hermit, recently relocated to the Bahamas after being holed up for two years in the Desert Inn, which he'd purchased from Moe Dalitz. Insiders knew that the white-collar tycoons would soon be squeezing the mob out of its own creation. In Broccoli's version, the Hughes character was named Willard Whyte, owner of the Whyte House casino, and a pawn in a nefarious scheme to build a massive superlaser out of thousands of smuggled diamonds. Assisting Bond in saving both Whyte and the planet Earth was a beautiful diamond smuggler (rehabilitated by Bond, of course) named Tiffany Case.

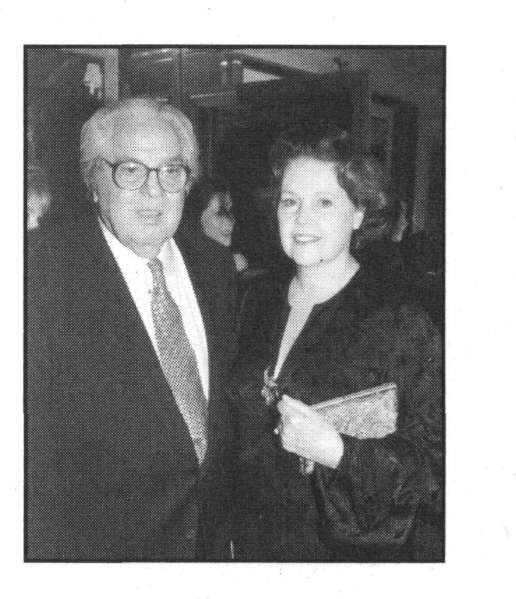

Cubby and Dana Broccoli, 1993 (private collection)

The film production would inevitably unite friends Broccoli and Korshak, since much of the story would be filmed in Korshak's Las Vegas dominion, with key scenes shot in his Riviera Casino. In the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film and Television, buried way down the Diamonds Are Forever credits, is this entry: "Legal advisor (Las Vegas): Sidney Korshak (uncredited)." But Korshak did much more than guarantee the cooperation of Vegas Teamsters—it appears he once again assisted the casting department.

Journalist Peter Evans first broke the story of Korshak's intervention, writing, "In Los Angeles, attorney Sidney Korshak, who was helping Broccoli set up location deals in Las Vegas, asked whether a small role could be arranged for actress Jill St. John, a close friend of his. She had been up for various Bond heroines before but never with success."58 According to the film's then twenty-eight-year-old screenwriter, Tom Mankiewicz, Jill was given a small supporting role, with Natalie Wood's sister Lana set for the lead role of Tiffany Case. "At some point Jill was going to play Plenty O'Toole, a lot smaller part than Lana would have played," Mankiewicz recalled. "And then she was mysteriously bumped up." Wood recently remembered her casting, saying, "I was contacted by my agent, who said, 'They want you to be in the Bond film.' I was considered for the lead role. I don't know how

Jill St. John with Sean Connery in Diamonds Are Forever (Photofest)

things got flipped around. I know that Jill was being considered for Plenty O'Toole, but it was supposed to be the exact opposite."*'59

For the young Mankiewicz, the shoot was an eye-opener. "We were up at Sidney's 'house,' the Riviera, which Eddie Torres was running," he remembered. "It was one of the last mob-run hotels in Vegas. Korshak, Jill St.

John, Sean Connery, and others stayed at the Riviera, while the crew stayed at the Happy Times Motel."

Five years after the film's release, when Pat DeCicco suffered a stroke and fell into a coma in Cubby's Beverly Hills home, Cubby was frantic to get him to his New York doctor. When no planes were found on short notice, Broccoli called Korshak, who knew that pal Frank Sinatra had millionaire Faberge perfume-company chief—and airplane owner—George Barrie as a guest at his Palm Springs home. Korshak called Sinatra and obtained the Barrie jet, which whisked DeCicco off to New York, a rescue that revived him from his coma long enough to get his affairs in order.60

As the summer of 1972 wound down, Korshak's confidence was soaring.

According to a top FBI source, in August 1972, Korshak made a $22-per-share offer to purchase one hundred thousand shares of Kerkorian's MGM, a failed bid that would have given him controlling interest in the company.61

*Hoffa's wasn't the only release bought from Nixon by the mob. As president, Nixon pardoned Phil Levin's pal Angelo "Gyp" DeCarlo, described by the FBI as a "methodical gangland executioner." Supposedly terminally ill, DeCarlo was freed after serving less than two years of a twelve-year sentence for extortion. Soon afterward, Newsweek reported the mobster was not too ill to be "back at his old rackets, boasting that his connections with [singer Frank] Sinatra freed him."

In FBI files released after Sinatra's 1998 death, a memo of May 24, 1973, describes Sinatra as "a close friend of Angelo DeCarlo of long standing." It adds that in April 1972, DeCarlo asked singer Frankie Valli (when he was performing at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary) to contact Sinatra and have him intercede with Agnew for DeCarlo's release. Eventually, the memo continues, Sinatra "allegedly turned over $100,000 cash to [Nixon campaign finance chairman] Maurice Stans as an unrecorded contribution." Vice-presidential aide Peter Maletesta "allegedly contacted former Presidential Counsel John Dean and got him to make the necessary arrangements to forward the request [for a presidential pardon] to the Justice Department." Sinatra is said to have then made a $50,000 contribution to the president's campaign fund. And, the memo reports, "DeCarlo's release followed."

*Among them, Sam Sciortino, Peter H. Milano, and Joe Lamandri.

*Kerkorian continued to expand at an astounding pace. In 1986, he sold the MGM lot to Adelson's Lorimar Productions. In 2000, he masterminded a $6.4 billion buyout of Wynn's Mirage Resorts, at the time the biggest merger in gaming industry history; on September 13, 2004, Kerkorian sold his film division, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc., to

Sony for $2.9 billion, netting him more than $1.7 billion. Variety's Peter Bart wrote that Kerkorian was not only a victim of bad luck, but that he was "out of place in Hollywood . . . He had no real passion for the business . . . [and] never really understood the potential of the ancillary markets" (Variety, 4-25-05). In February 2005, with his Sony deal in hand, Kerkorian laid out $8.7 billion for the purchase of Mandalay Inc., creating a twenty-eight-casino company that will employ more than seventy-five thousand, include seventy-four thousand rooms on the Strip, and control about 40 percent of its slots and about 44 percent of its table games. Among other properties, the merger gave Kerkorian control of the (new) MGM Grand, New York-New York, Bellagio, Mirage, Treasure Island, Monte Carlo, Mandalay Bay, Luxor, Excalibur, and Circus Circus.

Although a career of buying and selling companies in the entertainment and leisure industries has made Kerkorian a billionaire, he remains unaffected in person. Longtime friend General Alexander M. Haig Jr. said, "For a billionaire, he's almost meek . . . I've never heard him raise his voice. It seems like he would just as soon have his actions speak for him."

*Others suggest that Korshak was honored by the inclusion of the Godfather movie character "Tom Hagen," the non-Italian consigliere to the Corleones. In the film, Hagen, much like the rumored Korshak intervention for Sinatra with Columbia's Harry Cohn, met with the president of "Woltz International Pictures" to get an up-and-coming Italian entertainer named "Johnny Fontaine" a role in an upcoming career-making war movie. The famous horse-head scene that followed was supposedly inspired by Korshak's alleged tactic. In the film, the threat was successful for the Corleones—Fontaine landed the part he wanted and became a big star, just as Sinatra had succeeded with From Here to Eternity.

Also like Korshak, Hagen was offered the vice presidency of a Vegas casino, when toward the end of the second film Michael tells Hagen he can take his "wife, family, and mistress and move them all to Las Vegas." Lastly, just as Korshak briefly ran afoul of his Chicago bosses with the booking of Dinah Shore into the competition's Vegas lounge, Hagen was similarly reprimanded for misplacing his loyalties, with Michael Corleone once warning Hagen that he was "not a wartime consigliere." Neither the fictitious Hagen nor Korshak was ever so careless again.

*On December 20, 1990, The Godfather Part HI premiered in Beverly Hills, and the Immobiliare reference was not lost on insiders such as Peter Bart, who noted that Charlie Bluhdorn had tried numerous times over the years to persuade Francis Coppola to direct a second sequel of The Godfather. Bart wrote that Bluhdorn unfortunately never once

sat down with Coppola to discuss his knowledge of Sindona, the assassination of Pope John Paul I, and other shadowy figures that he had met. Bart believed that if Bluhdorn had taken these steps, this might have prompted an earlier start to the production of The Godfather III, avoiding the sixteen-year gap between parts II and III. (Bart, Who Killed Hollywood?, 112-21)

*The man DeLaurentiis set up was Dino Conte, an alleged associate of Alo's and also the Lucchese and Colombo crime families, who went on to produce 48 HRS, Another 48 HRS, and Conan the Barbarian. (Wall Street Journal, 7-13-90)

*MacGraw and McQueen divorced in 1978.

*One Polanski friend said, "He told me that after his wife and baby were killed, he changed. He started having sex with young people because he couldn't bear to be with regular women. Regular women wanted commitment from him, and he felt he would be betraying Sharon if he got involved with another woman. So he went after these young girls. That way there was no commitment." (Kiernan, Roman Polanski Story, 229)

*DeCicco was married for a time to millionaire fashion designer Gloria Vanderbilt, later the mother of CNN's Anderson Cooper. Among others DeCicco brought to Hughes was Elizabeth Taylor. (Deitrich and Thomas, Howard, 27S)

†The seventeen Bond films Broccoli was associated with were reported to have earned $1 billion worldwide by the time of his death in 1996.

*Other interesting casting included singer/actor Jimmy Dean as Whyte/Hughes, an ironic choice given that Dean was at the time performing in Hughes's Desert Inn. And when Sean Connery initially passed on reprising the Bond role, the part was given to Korshak friend John Gavin, who was forced to withdraw when Connery signed on after having been given a record-breaking $1.25 million fee, all of which he donated to his charity.