As KORSHAK APPROACHED what is retirement age for most Americans, he continued brokering labor peace at his regular pace. Slowly, however, his financial success became a point of criticism among those who regularly paid his exorbitant fees in exchange for little more than a few phone calls. "Sidney was not cheap on his fees," remembered friend and colleague Leo Geffner. "My tongue used to hang out, seeing him make in five minutes what I made in an hour. Most lawyers charged by the hour, but his flat fee: 'Fifty thousand.' It may take just one or two short lunches at the Bistro. And he never carried a yellow pad like most lawyers. He wrote everything down on an envelope, if you can believe that."1

Where Were They When Capone Needed Them?

In 1973, soon after attending the February 9 funeral of Ralph Stolkin in Palm Springs with Tony Accardo,2 Korshak was paid $300,000 for his minor role in facilitating an offshore tax dodge for the Supermob's Charlie Bluhdorn and Lew Wasserman. Three years earlier, Paramount's Bluhdorn had persuaded Wasserman and MCA-Universal to enter into a foreign partnership, Cinema International Corporation (CIC), an unethical masterstroke that allowed the companies to avoid both U.S. antitrust laws and U.S. taxes. Universal and Paramount would later form a distribution partnership called Universal International Pictures (UIP), referred to by Edward Epstein as "a highly profitable off-the-books foreign-based corporation."3

The concept, a mirror of the Pritzkers' Castle Bank arrangement in the Bahamas, allowed the merger to pool overseas resources for film distribution, hide its profits in an Amsterdam bank, then use complex "flow-through" subsidiaries to bring the untaxed lucre back into its own U.S. banks. Nicknamed a Dutch Sandwich since the client's money was hidden between a sham corporation based in Amsterdam and a sham trust in Curacao (Dutch Antilles), the scheme allowed the customers' income to be brought into the United States disguised as untaxable "loans" from the Caribbean bank. One banker working for Curacao's Credit Lyonais Nederland Bank admitted to Time magazine that he had no qualms about helping U.S. companies and individuals dodge taxes. "Many of your largest corporations, many of your movie stars, do much the same thing here," the banker said. "We wouldn't want to handle criminal money, of course. But if it's just a matter of taxes, that is of no concern to us."4 The banker might have had a hard time convincing Al Capone's family that tax evasion and criminality were not the same thing.

MCA executive George Smith openly admitted that vast profits accrued from the setup. "I would say that, on the average, one hundred to two hundred million tax dollars were deferred every year," Smith said. "Generally, we put it in a bank and got interest." Paramount's new COO, Frank Yablans, stated frankly, "It was a brilliant tax dodge."5 The intricate construct became a template for Hollywood conglomerates that would outlive its creators.* It would also herald a new era, one where tax lawyers eclipsed all others in importance in the film business. These facilitators favored creative accounting measures such as EBIDTA (earnings before interest, depreciation, taxes, and amortization), which, by allowing the studios to postpone the reporting of losses, gave a false impression of earnings to potential investors.

Soon, numerous high-rises appeared on the West Hollywood skyline, housing the lawyers that run the town to this day. The towers themselves were often financed using the Dutch Sandwich.

Assisting Hollywood's assault on the IRS were the likes of Senator Thomas Kuchel, the minority whip on the Appropriations Committee (and a partner at Wyman, Bautzer), who introduced legislation that would allow producers to understate their taxable gross income by 20 percent—the legislation was also lobbied for hard by the likes of Governor Ronald Reagan. Lew Wasserman, with his extensive ties in Washington, worked overtime to see the enactment of the 1971 Revenue Act, which allowed the film and television industry to define their product (films and television programs) as equipment and machinery, thus becoming eligible for a traditional 7 percent tax write-off for industry that had begun in 1962. The March 1972 issue of Variety reported that "97% of [MCA's] profit increase last year is directly attributable to the new tax rules." Universal and the other studios quickly joined Disney in a suit aimed at recovering back credits dating to 1962, a successful effort that saw them receive another windfall totaling almost $400 million.6 The credit was then raised to 10 percent, and the benefits multiplied. In addition, one clause in the legislation allowed movie investors to reap an astounding 100 percent indefinite tax deferment on half of all profits from exported films.7

Wasserman, Korshak, Kuchel, and Reagan were not the only actors working to feather Hollywood's nest. Also looking out for the financial health of the movie moguls was Jack Valenti, head of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA). Valenti was a former Houston, Texas, adman and special assistant to President Lyndon Johnson, who was brought to the White House after the assassination of President Kennedy in November of 1963. In 1965, Wasserman and attorney Ed Weisl Sr. (the man who had assisted Korshak in working out the details of Bluhdorn's purchase of Paramount and was also a director the Chicago Thoroughbred Enterprises and was a longtime friend of Johnson's) obtained LBJ's permission to headhunt Valenti and bring him to Hollywood (Valenti had earlier recommended to Johnson that Wasserman be named secretary of commerce, which Johnson proposed, but Wasserman declined).

A flamboyant attention seeker, Valenti took to Hollywood as if he were born there and for the next four decades would lobby hard in Washington for legislation that enabled the movie moguls to enjoy tax benefits (thanks to what was essentially protectionist lawmaking) unavailable to the average hardworking American. Valenti's view was that anyone involved in what he believed to be the precious film business was entitled to special financial treatment. And Wasserman's MCA-Universal profited more than any other; as one studio head put it, "The MPAA wagged to Lew's desires."8

In the years that followed, another key player in offshore tax schemes was Peter Hoffman, a brilliant attorney who had in 1974-75 clerked for none other than Paul Ziffren's great friend U.S. district court judge—and former tax attorney—David Bazelon. Hoffman became a specialist in the Dutch Sandwich, using it to become the architect and CEO of Carolco Pictures, a major independent player that, as a result of creative offshore financing, was able to finance such hits as the Rambo pictures, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Total Recall, Cliffhanger, and Basic Instinct. (In a December 1996 indictment for tax evasion and filing a false income tax return, the Justice Department charged that Hoffman treated income of more than $400,000 as "sham loans" to avoid paying taxes. In its trial brief, the government charged that Hoffman had created a "deferred compensation scheme" to obtain more than $1 million in tax-free income. Simultaneously, the IRS audited Carolco partners Andy Vajna and Mario Kassar and returned a $109.7 million tax assessment against them. The bulk of the claim focused on earnings by the partners' offshore companies that were set up in tax-haven countries such as the Netherlands Antilles—i.e., the Dutch Sandwich. In 1998, Hoffman pled guilty to one count of filing a false tax return and paid a puny $5,000 fine. Carolco had already closed shop.9 Under the banner of C-2 Productions, Kassar would resurface as the producer of such films as Terminator 3 and The Kingdom of Heaven.

In 2002, Paramount exec turned Variety editor Peter Bart described Hoffman's legacy: "Peter Hoffman, a lawyer-turned-producer, earned a certain renown years ago for creating such an arcane legalistic lexicon that no normal mortal could understand what he said. Now many lawyers have emulated the Hoffman model."10

The new focus on international profits also had a chilling effect on the artistic merit of the movies that were now deemed most desirable by the new multinational studios; gone were the days when the major suppliers released the likes of To Kill a Mockingbird and On the Waterfront. In their place were now cartoonish action movies whose minimal dialogue required no translation in order to appeal to the lowest-common-denominator audience in many countries simultaneously. For astute observers, this effect represented the most insidious legacy of the Korshak-Wasserman international design, a trend that regrettably continues to the present day.

In 1973, CIC was having problems convincing MGM to join its offshore party—MGM was demanding that its television productions be included in the operation, an idea that was not part of the original plan. The impasse forced Paramount attorney Art Barron to do what so many had done before: "I got out my Korshak number. I said, 'Sidney, this is where we're at.' He said, 'Hold your ground.' "

Just as he had done for Bob Evans with the Pacino casting, Korshak once again called MGM owner Kirk Kerkorian, who was still struggling to pay for the construction on the MGM Grand in Las Vegas; Korshak knew the pending deal with CIC would give him enough cash for the project. According to Barron, within thirty minutes Kerkorian had taken MGM's demand off the table. Soon thereafter, Barron received a piece of SIDNEY KORSHAK, COUNSELOR-AT-LAW stationery that stated simply, "Fees—$50,000." Although a shock to Barron, who typically paid hourly fees to attorneys, the bill was paid on orders of Lew Wasserman.11

In the following days, Kerkorian and Korshak worked out the fine points at the Bistro, where the deal was soon inked on October 25, 1973.12 For bringing aboard Kerkorian, an addition valued at $17 million to CIC, Korshak billed CIC another $250,000.13 Like Wasserman, Charles Bluhdorn had no problem with the fee. "Mr. Korshak was very close to Wasserman and Kerkorian and played a key role as a go-between," Bluhdorn later told Sy Hersh. "It was a very, very tough negotiation that would have been broken down without him."14 However, MCA senior executive Berle Adams bristled at the oft-heard suggestion that Korshak was responsible for the formation of CIC. "Sidney had nothing to do with it," Adams said recently. "I was there—it was all Bluhdorn's doing."15

A world away from Dutch Sandwiches and heady CIC negotiations, UFW leader Cesar Chavez was locked in mortal combat with his Teamster rival for the hearts and minds of Northern California's migrant farmworkers. As he had in 1966, Chavez would once again enter the domain of Sidney Korshak, not because of Korshak's work for farmers like Schenley, but because of his long-standing allegiance to the Teamsters.

Since the Schenley settlement, the UFW had engaged in a series of strikes and boycotts against growers (most notably of lettuce and table grapes) who refused to allow Chavez's organization to recruit workers into its fold. In 1973, grape growers began signing sweetheart contracts with the Teamsters, even though the workers had, for the most part, never asked for Teamster representation. "[The growers] knew the Teamsters would let them off easier than Cesar would," said one veteran labor activist. "And instead of telling the growers to go to hell, the Teamsters accepted their invitation. It was a straight steal on the part of the Teamsters. They had been in the farm industry for thirty or forty years and they hadn't done a thing for these people. Then, after Chavez knocks his brains out for them, they tried to take it all from him."16

The move sparked violent confrontations between Teamster goons and migrant workers, resulting in injuries, deaths, and thousands of arrests for the Chicanos. In response, Chavez called for a nationwide boycott of table grapes. According to a nationwide Louis Harris poll, at one point some seventeen million Americans were boycotting grapes.

What seemed to imply the presence of Sidney Korshak was that the Teamster enforcers were ostensibly working at the behest of Western Teamster boss Andy Anderson, who, in turn, was understood to be a functionary of Sid Korshak. (The thugs came to be known as Anderson's Raiders, a bit of wordplay based on a band of Confederate Civil War rogues that went by the same name.) As Duke Zeller, the former adviser to four Teamsters national presidents, recently said, "Virtually every Teamster leader on the West Coast, in the Western Conference, answered to Sidney Korshak. Everything really went through Korshak, who by all accounts was very astute and very bright. He knew what he was doing and knew how to play the game, certainly with the Teamsters." Mafioso Jimmy Fratianno told Teamster leader Jackie Presser that he knew Korshak had orchestrated the attacks. "[Frank] Fitzsimmons heard that Andy got a payoff from the farmers in the Delano area," Fratianno said. "They wanted Chavez out of there. Andy and Jack Goldberger [of the San Francisco Teamsters] got Sid Korshak to work it out."17

The struggles played out for five more years. In 1978, newly elected DA John Van DeKamp was given a prognostication of the soon-to-be settlement, an eventuality that again conjured the Korshak name. "It's one of the most interesting Korshak stories that I remember," Van DeKamp said recently. "It involved [Herman] Blackie Leavitt, the international vice president of Bartenders' Union [Local 249] and a Las Vegas organizer. I didn't know him well—he had a checkered reputation. Blackie made an appointment to see me when I was DA. He came into my office in a sort of hush-hush way. He said, 'I want to tell you something. I want you to know that Sidney Korshak is going to be the intermediary between the Teamsters and the Farm Workers. I am going to tell you that in three months there is going to be a settlement between them that gets the Teamsters out of competition with the Farm Workers.' "18 Three months hence, Van DeKamp joined the ranks of those who marveled at the effect Korshak had on labor imbroglios when the two unions resolved the issue with an agreement giving the UFW sole right to organize farmworkers.

However, membership in the UFW later fell, in part due to disputes between Chavez and his followers, some of whom accused him of nepotism. (On April 23, 1993, Chavez died peacefully in his sleep at the modest home of a retired San Luis, Arizona, farmworker while defending the UFW against a multimillion-dollar lawsuit brought by a large vegetable grower. Since his death, the plight of the farmworkers has again reverted to the pre-UFW conditions, largely because of the massive influx of undocumented alien workers, which now make up 90 percent of the force.)

In 1973, after attending the February funeral of Ralph Stolkin in San Diego,19 Sid Korshak dabbled in a bit of nepotism, landing his son Harry a producer's job at Paramount. Harry (who some friends say was named after Harry Karl, not Sidney's father, Harry Korshak) had shown an early interest in the entertainment biz, appearing as an actor in episodes of the long-running television series The Donna Reed Show. Of course, Donna Reed and her husband were close friends of the Korshaks' and likely gave the nod to young Harry's TV debut.*

Nine years afterward, Paramount production executive Peter Bart was paid an unannounced visit by Harry's father, who had shown up to help accelerate his grown son's fledgling movie career, this time as a producer. Korshak informed Bart of a project that Bart had never heard of, surprising given Bart's position at the studio. For this film—a thriller entitled Hit! —Harry was to be the producer, and the project was to begin immediately. Bart remembered Korshak saying, "Peter, my son has not produced anything before. I would be greatly in your debt if you kept an eye on him. He doesn't have your savvy." Bob Evans's right-hand man had no choice but to offer his assistance. "When Sidney Korshak asked a favor," Bart later wrote, "it wasn't smart to decline, especially when it was such a reasonable one."20 According to Bart, right after his decree, Korshak borrowed Bart's phone and placed a call on a direct line to the most powerful man in the industry, Lew Wasserman (Jules Stein had resigned from MCA on June 5, 1973, making Wasserman the new chairman). The call raised the possibility that Korshak was asking Lew to donate some MCA talent to his son's endeavor (which eventually starred Billy Dee Williams and Richard Pryor)^

As it happened, Gray Frederickson, the coproducer of The Godfather, got the call to watch over Harry Korshak. Three years earlier, Korshak had prevailed upon Frederickson to hire Harry as a PA (production assistant) on the Paramount feature Little Fauss and Big Halsy, starring Robert Redford. Frederickson recently recalled getting the call from Sidney, who said, "We're sending Harry as a PA on the film." Now, during the start-up of the Hit! shoot, Frederickson said an incident took place that hinted that Daddy Korshak was also shepherding the film from afar. "This was a low-budget film and we were using nonunion drivers to cut costs," recalled Frederickson. "On the first night of the shoot in D C , the Teamsters showed up to demand work. This would have killed us financially, but they could have shut us down if we refused to hire them. Harry just said, 'I'll call Daddy.'"21 According to Frederickson, the Teamster contingent returned to the set soon thereafter, only this time their demeanor spoke volumes to the seasoned producer about the power of Sidney Korshak. "The Teamsters showed up and offered anything we needed for free," said a still awed Frederickson. "That's when it hit me."

In the end, Frederickson paid dearly for all his help with Harry's producing bow—young Korshak began an affair with Frederickson's socialite wife, Tori, the half sister of Mrs. Conrad Hilton. The recently divorced Harry ended up marrying Tori and went on to produce just two more, inconsequential, films, Sheila Levine Is Dead and Living in New York (1975) and Gable and Lombard (1976).

On October 1, 1973, soon after the Hit! premiere, Sidney hosted at his home the seventy-eighth-birthday party for George Raft.22

Eleven days later, the attention of Supermob watchers turned to Washington, where, on October 12, Judge Bazelon, chief of Washington's U.S. Court of Appeals, upheld Judge John Sirica's U.S. district court ruling, thereby forcing President Nixon to hand over the incriminating White House tapes to the Watergate special prosecutor, which he did on November 26, leading to his eventual resignation on August 8, 1974.

Twenty-three hundred miles away, Sid Korshak made a ruling in his own Supermob jurisdiction—Beverly Hills—the result of an altercation on a typical Beverly Hills late afternoon in the spring of 1974, as Bistro owner Kurt Niklas was preparing to make the transition from the lunch crowd to the dinner arrivals.

On this particular evening, one lunchtime party refused to leave in time for the dinner setup—an occasional problem for restaurateurs. But what made this case exceptional was that the party was headed by the charming but dangerous Chicago mafioso Johnny Rosselli, a man Niklas called "the asp" for his deadly stare. "Johnny Rosselli came in regularly in the afternoons," said former Bistro maitre d' Jimmy Murphy. "He started coming in there about 1965."23 Bistro headwaiter Casper Morcelli said of Rosselli, "He was nice to us for the most part, but he was a rough guy."24

Niklas said that Rosselli began getting habitually drunk and stiffing the bar, opting instead to fold the check into a paper airplane, floating it back to Niklas and barking, "Give this fucking check to your Jew friend Korshak!" Niklas said that he merely ate the loss, without telling anyone, especially Korshak.25 Actress and Rosselli "goddaughter" Nancy Czar explained Rosselli's behavior recently, saying, "JR [Rosselli] was pissed at Sid—he thought Sid was taking over his territory."26 Jimmy Murphy said Czar knew what she was talking about, as she and Rosselli were constant companions. "Rosselli used to date these beautiful women, like eighteen-year-old Nancy Czar, who was with him a lot," said Murphy. "He was taking good care of her, and she dined with him often at the Bistro. "*

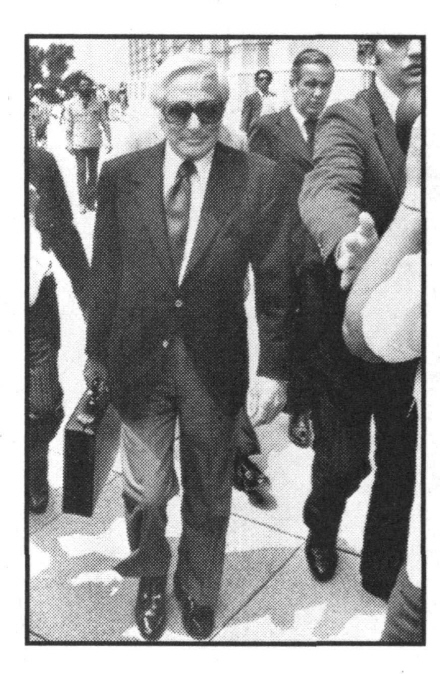

Johnny Rosselli walking to his June 24, 1975, Senate testimony (Corbis/Bettmann)

But, Czar's beliefs notwithstanding, there was another element to Rosselli's fury at Korshak, for he was among those who suspected Korshak of playing both sides of the law—which, in fact, he was. When he was imprisoned on the Friars Club scam, Rosselli had told a fellow inmate that Korshak was an FBI informant; Rosselli's key reason, also noted by others, was "that he had had never been prosecuted by the Federal Government."27

Czar was with Rosselli on the evening in question, as was Bugsy Siegel's pal Allen Smiley and mob attorney Jimmy Cantillon. "We got there before the dinner hour," remembered Czar, "when JR and Kurt, who he called 'the Nazi,' got into it." Murphy described how the situation evolved before a full house of patrons: "There was a section near the service bar where people could sit and have drinks. But by six or seven they had to vacate those tables because we needed them for dinner. One night Rosselli was there with a few friends who had a lot to drink, and he just said, 'No, I'm not leaving.'" Finally, Kurt came over and said, 'Look, you're leaving, I need this table.' As he was approaching the door, he turned to Kurt and called him an SOB. Out of nowhere, Kurt threw him a punch and hit him square on the jaw, knocking him through two doors. His head of white hair was all over his face. Rosselli got up, looked at Kurt, and said, 'This place is history!' " According to Niklas, the threat was much more frightening, with Rosselli, the man with the deadly stare, yelling back, "You're a fucking dead man, Kurt!"

It suddenly dawned on the Bistro owner just how imprudent his punch had been. "He was the real thing and his threats scared me shitless," Niklas later wrote. Morcelli saw the fear in Niklas's face. "Kurt was worried because Johnny was nuts," Morcelli recalled. said Niklas. "The one thing Sidney Roy Korshak was reputed to be able to do better than anyone else in the world was to talk privately to Johnny's

Of course, there was only one man to approach with a problem of this magnitude—Korshak. "If Rosselli was the asp, Korshak was the asp-eater," boss, the legendary Chicago godfather, Sam Giancana."28 What Niklas couldn't know was that Giancana was still living in "exile" in Mexico, having been banished by the Outfit's capo, Joe Batters Accardo. But that mattered little, since Korshak was even closer to Accardo. As Chicago FBI man from the seventies Pete Wacks recently noted, "In the seventies, Korshak made monthly visits to his suite at the Drake, where he met with Accardo and the others."29

On hearing of Niklas's careless cuffing of Rosselli, Korshak exclaimed, "Are you nuts? Check into a hotel and call me in the morning." When Niklas called back as instructed the next day, Korshak was at his minimalist best.

"Everything's okay," Korshak assured him.

"Are you sure?" demanded an unconvinced Niklas.

"Goddammit, what did I just say?" answered an irate Korshak. "Johnny's not going to do a fucking thing. Got it?" With that, Korshak hung up.

"Kurt's call to Sidney saved the day," Murphy said. "It was the last time we saw Rosselli." Niklas was more effusive: "I know Korshak saved my life."30 Months after the dustup, Niklas finally told Korshak that Rosselli had regularly made anti-Semitic remarks about him. "How come you never told me that?" Korshak asked. "I didn't want to cause any problems," Niklas answered.

Korshak's display of power illustrated that, although he was increasingly more "legit," he still maintained a powerful connection to old Chicago. Significantly, a 1974 FBI memo stated, "Korshak is undoubtedly best contact any LCN [La Cosa Nostra] anywhere has and conducts activity constantly for all LCN families, being in constant contact with [Gus] Alex whose assignment it is to 'handle him.' "31 On January 15 of that year, Korshak was observed meeting with Joe Batters Accardo in Palm Springs. According to an FBI informant, "The meeting concerned a liquor salesman union meetings [sic]. [Source] advised that election of officers to replace two who have recently died is to be held in future in New York. Korshak wanted to discuss with Accardo background of two candidates whom he is recommending . . . Korshak visited Accardo during the day and returned to Los Angeles in late afternoon."32

Korshak's name next surfaced that summer, albeit briefly, again in relation to his Nevada foe Howard Hughes. The Korshak linkage concerned testimony gathered after what came to be known as the Great Hughes Heist.

At one A.M. on June 5, 1974, four or five burglars entered the fortresslike office of Howard Hughes's holding company, The Summa Corporation, located at 7000 Romaine Street in Hollywood, in what was later concluded to be an inside job. The building contained twenty-five years' worth of handwritten Hughes memos, as well as personal and corporate files, and safes full of cash; it was the nerve center of his empire. In their four-plus hours on the scene, the burglars, who came equipped with acetylene torches, largely ignored the cash-engorged wall safes, more interested in a meticulous reading of the sensitive documents, occasionally remarking, according to the bound security guard's deposition, "Looky here, this is it!"

Interestingly, it was the sixth unsolved burglary of a Hughes office in the last five months. However, until this burglary, no papers had been taken—obviously the thieves were looking for something specific. This time, though, they hit the jackpot, filling up cardboard-box-loads of Hughes's personal files, and anywhere from $60,000 to $300,000, according to differing reports.33

There were many possible motives for the heist, including: with the Senate Watergate investigators hounding him, Richard Nixon had ordered the theft to destroy any evidence of the graft he had received from the billionaire over the years (on the very day of the burglary, Donald Nixon was to testify about the Hughes loans to the Senate investigators); or, Hughes himself had ordered it so that any record of the bribes and stock manipulations connected to his recent buyout of Air West would be beyond the reach of a Senate subpoena. FBI reports show that the Bureau was certain that the break-in was related either to Watergate or organized crime in Las Vegas. One Bureau report suggested that organized crime desired to steal Hughes's intel reports into the Mafia's stealing from his casinos "to maintain organized crime status in Nevada."34 The CIA even entered the investigation, the result of their secret alliance with Hughes (Project Jennifer) to raise a sunken Russian submarine from the floor of the Pacific.5' Like the FBI, the CIA also concluded that the affair had its genesis in a world very familiar to Sid Korshak. One CIA memo, based on a "fairly reliable source," stated, "The burglary in question was committed by five individuals from the Midwest and was mob sponsored . . . The contents are said to be highly explosive from a political view and, thus, considered both important and valuable to Hughes and others as well . . . Source believes [the material] is still being held in the Los Angeles area."35

Two weeks after the theft, according to later court testimony, a petty thief named Donald Ray Woolbright supposedly admitted to a witness that he held the stolen papers. Woolbright said he had been given them by "a man from St. Louis," adding that the papers, not the money, were the whole objective of the burglars, and that after the papers were lifted, they were spirited to Las Vegas.36

Vegas, the mob, the Midwest, Hughes—they all intersected the world of Sidney Korshak, whose name was first openly injected into the mystery when Woolbright showed the documents to Korshak pal Greg Bautzer and later to Korshak's nephew L.A. attorney Maynard Davis, hoping to fence them to Korshak. A witness who accompanied Woolbright testified that Bautzer expressed some interest in the papers, and Davis placed a call to "Uncle Sidney," who was supposedly out of town at the time. Davis then advised Woolbright, "If I were you, I'd drop it. You're playing with dynamite."

According to an LAPD report of August 25, 1976, Hughes's security chief Ralph Winte, who had earlier assisted the Watergate burglars in a Las Vegas burglary, said he had "received information that there were possibly two attorneys involved, Sidney Korshak and [Hoffa's St. Louis lawyer] Morris Schenker . . . if a sale [of the Hughes papers] was made, it would be through these attorneys." Schenker denied involvement, while Korshak, typically, refused comment.37

Although Woolbright was eventually charged in the crime, he profited from two hung juries in 1977 and 1978, leaving the break-in forever unsolved. Although the Senate Watergate Committee originally wrote a forty-page report that stated that the motive for the Watergate break-in was the Nixon-Hughes bribery, that document was suppressed at the last minute. Committee chairman Senator Sam Ervin said, "Too many guilty bystanders would have been hurt."38 Committee member Lowell Weicker added, "Everybody was feeding at the same trough."'*

On April 5, 1976, Hughes died at age seventy aboard a plane en route to Houston, ostensibly of kidney failure. However, his dehydration, malnutrition, and the shards of broken hypodermic needles buried in his thin arms suggested other factors to many. In the ensuing years, over forty wills and four hundred claimants surfaced to vie for part of Hughes's $2 billion estate, which was eventually settled with twenty-two cousins in 1983.^ One year after Hughes's death, author Michael Drosnin was allowed to see and photograph the explosive papers purloined from the Romaine office, which filled three steamer trunks and numbered some ten thousand pages. The documents, which became the basis for his 1985 book, Citizen Hughes, in fact showed that Hughes had bought countless U.S. politicians, lock, stock, and barrel.

In 1974, Jerry Brown, the thirty-six-year-old San Francisco-born son of Korshak pal, and former governor, Pat Brown, made his own bid for the governor's mansion. Although Jerry's political beliefs were complex at best, one aspect was a given: his potential for success would be predicated on a continued relationship with Supermob powers. In his youth, Jerry began to display a more complex understanding of government's social contract than his father. Not only was he skeptical of the "backroom deal" style of his Democratic Party, Brown was, like Ronald Reagan, equally dismayed with exaggerated New Deal handouts and the concomitant explosion in the size of government. Young Jerry was actually naive enough to believe that individual responsibility and altruism could overcome all the ills that infected the American system. California historians Kotkin and Grabowicz wrote, "Brown's revulsion against the consumption-oriented, materialistic world of his father at first drove him away from politics."39 Indeed, Brown spent four years in a Spartan Jesuit seminary before gaining a degree from Yale Law School in 1964. (Years later he would spend two years working with Mother Teresa in India.)

After a brief stint on the Los Angeles Community College Board, Brown ran for statewide office, becoming secretary of state in 1970. Almost immediately after assuming office, Brown admitted to confidants that his ultimate goals were, as Reagan's had been, not only the governorship, but the U.S. presidency. And in a state where media savvy and access to deep-pocket donors were more important than experience, anything was possible. When the 1974 contest rolled around, Reagan chose not to run again for governor in order to focus on his White House aspirations, prompting Brown to throw his hat in the gubernatorial ring, opposing a weak Republican candidate, state controller Houston Flournoy.

Although Brown had some philosophical differences with the world in which his father operated, he was also well aware that he could never afford the cost of a campaign without going to the same gentry and Supermob that had supported his father. When Brown enlisted electronics mogul Richard Silberman, the son of a Russian-Jewish immigrant junkman, as his chief fund-raiser, it quickly became apparent that the same Chicago money that had transformed California in the forties would continue to play a key role in the seventies. (Silberman would be convicted in a 1991 FBI drug-ring money-laundering scheme.) Thus, with a brilliant media campaign, massive contributions from the likes of Lew Wasserman, Jake "the Barber" Factor,40 and later Sidney Korshak, Brown defeated Flournoy by 175,000 votes. When he would run for reelection, his association with Korshak especially would become a major point of criticism and even mockery.

Predictably, Governor Brown's terms were typified by seeming contradictions. On the one hand, he clung to his Jesuit training and refused the trappings of his office—canceling a raise for himself, refusing to ride in limousines, and failing to occupy the ultramodern, new governor's mansion, which he referred to as the "Taj Mahal." With his chief of staff, Gray Davis, whom some referred to as having been mentored by his Bistro lunch companion Sid Korshak, Brown adopted some standard liberal positions, such as vetoing the death penalty (overridden), favoring the right to choose abortion, strengthening environmental regulation and conservation, and protecting the rights of migrant workers. Brown's populist style proved popular with voters, and by 1976 his approval rating was 80 percent. Brown attempted to cash in on this popularity with a last-minute run at the Democratic presidential nomination, but he started too late, and Georgia's Jimmy Carter took control of the presidential national stage.

Curiously, Brown soon evolved into what Kotkin labeled a "born-again capitalist," courting not only Asian businesses, but also American titans such as Bank of America, ARCO Oil, the Irvine Corporation, Pacific Lighting, Kaiser Steel, Warner Brothers Records, and even some subsidiaries of the Howard Hughes empire. Brown even infuriated his environmentalist base when he championed the refining of Indonesian liquefied natural gas at a facility located on a pristine section of central-California coastline; and the company involved was represented by father Pat Brown's law firm. The overtures led one crestfallen Brown aide to say of his boss, "He's gone to the corporations because that's where Jerry thinks the power is at."

Reagan's New Teammate

Jerry Brown was not the only California pol to recognize the importance of maintaining good relations with former residents of 134 N. LaSalle Street. Brown's gubernatorial predecessor, Ronald Reagan, who had eyed the White House for years, chose as his 1976 presidential campaign chairman a man who maintained intimate associations with numerous individuals who once kicked up their heels at the infamous Chicago address. Although he was already friendly with 134's Sid Korshak, Reagan reached out for more support from those connected to the Chicago seat of Supermob power.

Fifty-three-year-old Senator Paul Dominque Laxalt (R-Nevada) had first met Reagan in 1964 when the two worked on the presidential campaign of Senator Barry Goldwater, himself no stranger to the Vegas gambling venues controlled by the mob and Supermob. The two men went on to become best friends when both became new governors of neighboring states (Laxalt in Nevada) in 1966. Chief among Laxalt's campaign policy planks was his defense of those in the state's casino industry; his mantra on the stump was a denunciation of the feds, whom he accused of harassing the good men purveying Las Vegas gambling. It was therefore little surprise that his staunchest supporters became those with the most to lose from the "harassment."

The first inklings of Laxalt's curious coterie surfaced that year, when he chose as his fund-raising chief one Ruby Kolod, a former member of Moe Dalitz's Mayfield Road Gang and Cleveland Syndicate (see chapter 9) and Dalitz's partner in the Desert Inn. Just one year before his fund-raising assignment, Kolod had been convicted in a murder-extortion plot in Denver, Colorado—his appeal was pending during the 1966 campaign.41 Others who were close to Laxalt were Moe Dalitz, Sid Korshak, Allen Dorfman, Lefty Rosenthal, and Hoffa's attorney Morris Schenker.

When Laxalt's term expired in 1971, he turned to real estate speculation as his next venture, despite that his net worth was only just over $100,000.

Laxalt's chief goal was to construct a first-class, multimillion-dollar casino-hotel in Carson City, to be named the Ormsby House. The proposal called for a 237-room "gambling palace" to be built on seven acres directly across from the state capitol; a secret part of the proposal was that Laxalt invest none of his own money in the project (although he ended up contributing just over $900). Although initial loans were secured from Nevada banks, Laxalt was well short of his financial goal. Thus, according to Las Vegas FBI agent Joe Yablonsky, Laxalt chose, as so many had before, to meet with the Fixer, Sid Korshak, who brought along Del Coleman for the strategy session. But before Korshak agreed to help, he wanted a couple political favors up front: Laxalt proceeded to accompany Del Coleman to Washington for his ongoing SEC Parvin testimony (see chapter 16), and to write a letter to President Nixon on behalf of Jimmy Hoffa's pending early parole. Laxalt's January 26, 1971, letter to "Dear President Dick" extolled the virtues of both Hoffa and "Al Dorfman, with whom I've worked closely the past few years." Laxalt laid it on thick, writing that "Hoffa and Dorfman and their activities here have been aboveboard at all times, and they have made a material contribution to the state."

Laxalt was soon jetting off to Switzerland with Del Coleman on Coleman's dime before visiting the First National Bank of Chicago, where they met with VP Robert Heymann, personal banker to Korshak pals Coleman and Joel Goldblatt—both had been set up with Heymann by Korshak, who was close friends with Heymann's father, Walter, also a VP of the bank. As promised, Heymann gave Laxalt a nonsecured $1 million loan, followed by three more loans totaling $8.3 million. The FBI said that the Outfit was "instrumental in the loans."42

"It was astonishing," the FBI's Joe Yablonsky would say later, "but while governor, Laxalt had a meeting with Dorfman, Korshak, and Coleman and then wrote a letter to President Nixon extolling the virtues of Jimmy Hoffa, and Korshak arranges his Chicago loan right after that. It was pretty blatant. Laxalt began to emerge in my mind as a tool of organized crime."43 In a secretly recorded conversation made a decade later, Laxalt's former sister-in- law said that her husband, Peter, who was also a partner in the Ormsby venture, accompanied his brother Paul to Palm Springs for the meeting, and that he told her "every hood in the nation was there."44

Not surprisingly, the largest individual investor in Ormsby House was another Korshak neighbor from 134 N. LaSalle, Hoffa pal Bernard Nemerov, also an investor in and operator of Korshak's Riviera. Nemerov chipped in some $550,000 to Laxalt's casino, but according to Las Vegas FBI special agent Joe Yablonsky (1980-84), Nemerov had reason to know it was a sound investment. "Nemerov was there to get the skim out," Yablonsky said.45

More Ties to the Outfit Are Severed

As Sid Korshak's favored California pols such as Reagan and Brown continued their ascendance, his own independence from the Chicago bosses became complete with the June 18,1975, murder of Sam "Mooney" Giancana in the basement of his Chicago home. A year before Johnny Rosselli met a similar fate, Mooney had placed himself in an impossible position, and thus, to those on the inside, the clipping of the sixty-seven-year-old former boss came as no surprise. Almost a year earlier, Giancana had been booted out of his Mexican exile by local authorities and handed over to the Chicago FBI. Thereafter, he attempted to lie low in his small suburban house, making the occasional trip to Santa Monica to squire his current love interest, Carolyn Morris, a former wife of Broadway composer Alan Jay Lerner, and also a former roommate of actress Lauren Bacall.46

This seeming serenity did nothing, however, to mollify Joe Batters Accardo and his current street boss, Joey "Doves" Aiuppa, who had two major disputes with the aging don: Giancana continued to ignore Accardo's demands that Chicago be cut in on the vast profits he had accrued in Mexico (the result of offshore gambling operations with Hy Larner),47 and the fear that Giancana, who was extremely ill, would likely testify before the Senate in the coming weeks, as per a subpoena.* It was well-known that Giancana would do anything to avoid going to prison again, especially in his frail condition. Thus it was decided that, for the good of all, he had to go. Recent interviews with a close personal friend of Aiuppa's driver Dominic "Butch" Blasi (previously Giancana's driver) indicate that Blasi late in life admitted to the shooting, as so ordered by Accardo.

On July 30, less than six weeks after Mooney's whacking, former Teamster boss and Korshak associate Jimmy Hoffa disappeared forever. His fate, like Giancana's, was sealed when he refused to toe the line of the new Teamster powers—in this case, President Frank Fitzsimmons, who had, during Hoffa's incarceration, forged real Mafia alliances with the likes of East Coast bosses Tony Provenzano of New York and Russell Bufalino of Pennsylvania. Not only had Hoffa recently declared his desire to retake the union, ahead of the timetable implicit in his early parole, but he had also, like Giancana, given signals that he would "sing" to the feds, in this case, the FBI. Both the feds and outside Hoffa experts came to believe that Provenzano and Bufalino used a trusted Detroit mobster named Anthony Giacalone to lure Hoffa to his fatal encounter. The FBI called Giacalone's propensity for violence in Detroit "legendary."48

As with the Giancana rubout, insiders developed their own rumors about Hoffa's disappearance, and oftentimes their whispers included the name Korshak. Just days after the Hoffa disappearance, Korshak's partner in the Bistro, Kurt Niklas, asked Sidney, "What do you think happened to Hoffa?" According to Niklas, Korshak threw him a "steely glance" and warned, "He's dead, and don't ever mention his name again."49 Of course, it was weeks before the press and authorities came to the same conclusion.

Similarly, Las Vegas investigator Ed Becker noticed a curiosity surrounding Korshak and Hoffa's snatching: "After the disappearance of Hoffa, Korshak and Dorfman took off for Europe. They were conveniently not in Chicago. So it was interesting."50

What Niklas and Becker likely didn't know was just how well Korshak was plugged in to the very man whom the Bureau and other Hoffa experts would later suspect of enticing Hoffa to his doom. According to an LAPD Intelligence report, none other than Anthony Giacalone was not only a friend of Sid Korshak's, but had stayed at his La Costa condo in 1969. 51

Whatever Korshak's level of knowledge regarding Hoffa's fate, it seemed to give him little comfort after returning from his European getaway with Dorfman. "Korshak started traveling with a bodyguard after Hoffa disappeared," said a Labor Department investigator who had followed Korshak's career for nearly twenty years. "Lew Wasserman beefed up security at his home around the same time."52

With Hoffa gone, the mob's infiltration of the Teamsters was virtually unchecked. Consequently, by the spring of 1976, L.A. mafioso Jimmy "the Weasel" Fratianno cooked up another scam involving the union's health plan, and when the rip-off did not proceed as quickly as he wished, the Weasel brought Sid Korshak into the fray.

At the time, Fratianno, one of the most feared mob hitmen, was attempting to sell Andy Anderson's West Coast Teamsters a questionable dental plan, which, like the health plan involving People's Industrial Consultants, would see massive skims to the underworld. "I've got to make some money," Fratianno had said to his San Francisco Teamster ally Rudy Tham, the head of freight checkers Local 856, the city's second-largest Teamster union. It was Tham's membership roster that Fratianno hoped to use as foils in the plan. Fratianno explained the operation to Johnny Rosselli: "You pick the dentist and the union gives him a contract to do all the dental work for the members of the locals signed up and their families. Dorfman's company, Amalgamated Insurance Agency, processes all medical claims and authorizes payment, which means he controls the whole thing. So now we can play some games. Number one, the dentists kick back to certain people so many dollars for each member signed up; and number two, Dorfman can submit phony claims and nobody's the wiser. It's a sweet setup, believe me."53

A frustrated Fratianno waited for months for Anderson to rubber-stamp the plan, eventually turning to Cleveland Teamster boss Jackie Presser for advice.

"Go see Sid Korshak," Presser said. "Andy's his man. You believe me, Jimmy. This Korshak can take care of the whole thing with one phone call . . . This's the smoothest sonovabitch in the business. There's nothing he can't fix."

Per custom, Sidney met the Weasel at his Bistro corner table, escorted him outside to the bench Korshak reserved for sensitive negotiations, and heard the pitch.

After a few minutes, Korshak merely said, "I'll talk to Andy and get it straightened out . . . Jimmy, I'll do the best I can, believe me. But, please, don't call me on the telephone.' "54

When more weeks went by with no movement, Fratianno took up the matter with Korshak's Chicago patrons, meeting first with street boss Joey "Doves" Aiuppa. Fratianno was thereupon told what so many had been instructed before: that he should have no contact with Korshak. "The less you see him the better," Doves said. "We don't want to put any heat on the guy." Then he summed up Korshak's life, as interpreted by the Chicago bosses: "Let me explain something, Jimmy. Sid's a traveling man. He's in everybody's country, but he's our man, been our man his whole life. So, you know, it makes no difference where he hangs his hat. Get my meaning?"

When Fratianno started to argue, Aiuppa started laughing. "Jimmy, you're not listening. He's got a permit. We gave him one. Understand? Don't put any heat on Sid. We've spent a lot of time keeping this guy clean. He can't be seen in public with guys like us. We have our own ways of contacting him and it's worked pretty good for a long time."

But Fratianno was too hot to heed the warning. He went right back to the Bistro and, in an attempt at intimidation, showed up with mob tough guy Mike Rizzitello. Again they sat on the little bench outside the restaurant, as Korshak explained that he didn't actually control Anderson, and that Anderson was not returning calls.

"Then the guy's going to get hurt," Jimmy warned. "I told you last time, Sid, I don't want no stories. As far as I'm concerned, that's bullshit. You know this fucking Andy better than I know my own brother."

"Jimmy, I don't want to argue with you," answered an unfazed Korshak. "I'll talk to him again. What else can I do?'

"Look, we don't want to take this into our own hands," said the imploding mobster. "We're not asking for the moon. All we want's for him to give Rudy what he's entitled to. And by Christ, Rudy's going to get it, one way or another."55

Continued inaction pushed Fratianno to the next level. When an answer from Korshak was not forthcoming in the following weeks, a dead fish was deposited in Korshak's mailbox, a transgression that was quickly reported back to Joe Batters Accardo. Now, the Weasel was ordered back to Chicago to explain himself to Korshak's closest friend in the Outfit, boss Accardo.

Joey Aiuppa opened the meeting, telling Jimmy, "I told you last time, we don't allow nobody in the family to talk to this guy. We don't want no fucking heat on him." After hearing the Weasel's denials that he had put the dead fish in Korshak's mailbox, the boss uttered his pronouncement: "Jimmy, Sid's been with Gussie over thirty years and Gussie's with us. Sid's a good provider for our family and we don't want nobody to fuck with him. I appreciate your problem, but we don't want him seen with nobody. We don't want nobody muscling this guy. I can't make it no plainer than that. He's off-limits. That's it, Jimmy."

Fratianno made one last foray into the West Coast Teamster scam, this time going directly to Andy Anderson at the Teamsters headquarters in Burlingame, California—once again with the menacing Mike "Rizzo" by his side. Once alone with Anderson in his office, Rizzo closed the door behind them. A few menacing words later, and Anderson caved.

"All right, Jimmy," Anderson said, "tell Rudy to call me and we'll straighten it out."

"Andy, you do it," warned Fratianno. "We don't want to come back here a second time."

In short time, Fratianno and Tham got their dental plan, but the victory was short-lived. Like Henry Hill, of GoodFellas (1990) fame, Fratianno became a government witness in 1977 when he was confronted with a raft of charges by the government, and the simultaneous realization that the Los Angeles mob had ordered him killed. In 1978, Fratianno was sentenced to two concurrent five-year sentences, the result of a plea bargain to testify and go into witness protection, where he spent the next ten years. His matter-of-fact accounts of Mafia "hits" and operations helped convict more than two dozen members of the Mafia around the country during the 1970s and 1980s. In one 1980 trial that led to the racketeering convictions of five Mafia figures, Fratianno admitted that he had committed five murders and participated in six. He later admitted to four more hits. He was dropped from the witness protection in 1987 after the Justice Department said further payments might make the program appear like a "pension fund for aging mobsters." In retirement, Fratianno was the subject of two books, The Last Mafioso (1981) and Vengeance Is Mine (1987), both of which he claimed never to have read, and appeared on several television talk shows. Aladena "Jimmy the Weasel" Fratianno, the former mob boss who turned government witness, died in his sleep in July 1993, at age seventy-nine in an undisclosed U.S. city, where he was living under an assumed name.56

In 1980, a federal jury convicted Tham for embezzlement of union funds.

Korshak has been very active in this sort of investment [real estate and private industry] and since he carries considerable weight in determining where Chicago funds are invested it now appears some of the Chicago Family's surplus is in the film industry.

1977 FBI MEMO57

Korshak ended 1975 with another show of film business acumen, this time involving the planned remake of the classic 1933 movie King Kong. His actions amplified the FBI's growing interest in the Chicago Outfit's latest infiltration into the movie business.

In 1975, according to King Kong chronicler Bruce Bahrenburg, "Paramount was looking for another 'big' picture in the same league as their recent blockbuster, The Godfather and the forthcoming The Great Gatsby."58 When the Kong project was announced in the trades that year, Lew Wasserman's Universal Pictures sued the new film's director Dino DeLaurentiis for $25 million, claiming Universal alone held the rights to the remake of the original 1933 RKO production. Universal simultaneously filed suit against RKO, which had sold the rights to DeLaurentiis, after it had supposedly already done the same to Universal.

DeLaurentiis then countersued Universal for $90 million, and the legal morass became more entangled with each successive day. "The legal issues surrounding the copyright to Kong," Bahrenburg wrote, "are as puzzling as a maze in a formal British garden."59 With the lawsuits casting a shadow over the film, Paramount nonetheless went ahead in early January 1976 with principal photography, making it imperative that the legal issues be resolved. Although the courts had failed to bring about a deal, there was, of course, one man who was famous for just that, and given Sidney Korshak's great connections at both Paramount and Universal, he was the natural choice to mediate the dispute. Or as DeLaurentiis later said, "The only way to get through to Lew is to talk to Sidney."60

With DeLaurentiis's office located on Canon Drive, just a few steps from Korshak's Bistro, it was merely a matter of walking up the street to enlist Sidney. According to a source close to the production, a luncheon was arranged at Korshak's Bel-Air home between executives of Paramount and Universal (MCA).* "Sidney was the court," said the source. "In a couple hours, a deal was arrived at that made everybody happy. Sidney had done more over his lunch hour than dozens of high-priced attorneys had done in eight months." The source, a producer at Universal, added that Korshak was paid a $30,000 fee for his two-hour business lunch.61 DeLaurentiis himself would later corroborate the fee.

There may have been a hidden agenda at play that explained both Korshak's and DeLaurentiis's desire to get the movie going. In a recently released memo describing a tip from an undisclosed source, the Los Angeles FBI Field Office noted:

[Source] indicated that Korshak was bringing in laundered money, skim money, mob money from the Chicago-Las Vegas areas for the purpose of producing a revival of the classic film King Kong, which is a joint venture between Paramount Studios, a subsidiary corporation of Gulf &C Western, Universal Studios, which is a subsidiary of MCA, and [deleted]^ of Rome, Italy. According to [source], Korshak is alleged to be handling $12 million in illicit funds gathered through skimming in Las Vegas and Syndicate money in Chicago . . . [Source] further points out that Korshak is also handling "laundered" money controlled by mob interests in Chicago and Las Vegas in the production of a second movie in production now at United Artists, which is being produced by Joseph Levine, entitled A Bridge Too Far.

It is [source's] understanding that King Kong has been budgeted at 25 million dollars and that at the rate of production expenditures thus far, it will exceed 25 million dollars. [Source] offered that the excessive costs of the production would add to the concealment of illicit funds, in his judgment.*'62

Variety later reported that Universal agreed to allow Paramount to make the film, with Universal maintaining the rights to a future remake. "I am very pleased," DeLaurentiis told the press, "and would like to thank MCA's Lew Wasserman and Sid Sheinberg for their understanding and generosity in making such accommodations possible." And as per custom, Sid Korshak's name never surfaced in connection with the resolution.

Despite the coverage given to the Kong settlement by the fourth estate, the press nonetheless avoided addressing the "elephant in the room": Why did Universal cave so quickly, and with no equivalent benefit? Some have posited that DeLaurentiis's production of Universal's The Brink's Job in 1978 (another film that required Korshak's intervention with the Teamsters) was the quid pro quo.* However, the word among insiders was that Korshak had decreed that DeLaurentiis give Universal a percentage of the Kong profits. 63 DeLaurentiis's assistant to the producer Fred Sidewater said, "The settlement cost Dino five million dollars." Sidewater also clarified that the unpublicized subtext to all the arguing was marketing rights. "The reason for all the fights was that they wanted to put the ride in Universal's theme park after all the success with the Jaws ride. We gave them the merchandising rights as a compromise."64 Although panned by critics, the $24 million movie made $46 million in profits. But Universal's King Kong thrill ride, which operated for over two decades, undoubtedly made more profit than Dino's movie.

According to Korshak friend and Hilton Hotel general counsel E. Timothy Applegate, Korshak's performances regarding Valachi and Kong ingratiated him with the producer. "While eating at the Bistro, Sidney told me how Dino DeLaurentiis thought the sun rose and set on him," recalled Apple-gate. "He told me how he had helped Dino with King Kong, and that Dino later gave him a new Ferrari for his help. Sidney, who was over seventy at the time, said, 'What the hell am I going to do with that?' "65

In 2005, Universal finally began production on its Kong remake, with Oscar-winning Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson at the helm.

Sid Korshak's latest triumph added still more luster to an already vaunted reputation. Toward the end of 1975, actor David Janssen's wife, Dani Greco Janssen, was inspired to further refine Joyce Haber's demarcation of Korshak's "A-list" to include an exclusive subset that she called The Big Six, consisting of the Korshaks, the Ziffrens, and the Wassermans.66 In March 1976, Korshak exerted his power in Las Vegas again, this time in another broadside against his foe Howard Hughes's Summa Corporation. On this occasion, Korshak orchestrated a seventeen-day strike by the Hotel and Restaurant Employees and Bartenders International Union against a group of casinos and hotels, six of which were owned by Summa. Typically, none of the hotels or casinos that employed Korshak's services were affected.67

On May 4,1976, Korshak renewed his passport, falsely writing on the form that his "permanent residence" was 69 W. Washington Street in Chicago—which was actually his brother's law office—and advising that he planned to travel throughout England, France, and Italy for two months in the summer of 1976. *

*The tax dodge courtesy was also offered to millionaire movie stars, who have since become incorporated in the Netherlands and receive their income as tax-free loans. With Wasserman viewed as the most adept at the offshore schemes, many top actors had still one more huge incentive for signing up with MCA.

*Harry played "Steve" in episode #7.16, "Overture in A-flat," which aired December 31, 1964.

^[Hit! opened on September 18, 1973, and told the story of a federal agent whose daughter dies of a heroin overdose, and his determination to destroy the drug ring that supplied her. The ambitious action flick received some good, but overall mixed, reviews.

*Czar had an interesting career herself, appearing in a number of Elvis Presley movies, including Girl Happy (1965) and Spinout (1966), and becoming a B-movie queen in such low-budget classics as Ray Dennis Steckler's Wild Guitar, playing opposite the legendary Arch Hall Jr.

*The Soviet ballistic-missile submarine (SSB) K-129 sank off Hawaii on April 11, 1968, probably due to a missile malfunction, and was later located by the CIA in 16,500 feet of water. Hughes's contribution to the partnership was the Glomar Explorer, a sixty-three-thousand- ton deep-sea salvage vessel built specifically for the top-secret operation. The ship was built under the cover story that she was a deep-sea mining vessel, ostensibly intended to recover manganese nodules from the ocean floor. Half of the sub was eventually raised, and the bodies of the Soviet sailors recovered inside were buried at sea.

* Among the many recipients of Hughes's money over the years (in addition to Nixon) were Lawrence O'Brien, Senator Joseph Montoya (who was a member of the Senate Watergate Committee), Bobby Kennedy, President Lyndon Johnson, and Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

†The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Hughes Aircraft was owned by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which sold it to General Motors in 1985 for $5 billion. The court rejected suits brought by the states of California and Texas, which claimed they were owed inheritance tax on the Hughes estate.

*Giancana had recently undergone two problematic gallbladder surgeries and was simultaneously called to testify before a Senate committee looking into the Castro assassination plots of the early sixties that linked both the CIA and the Chicago Outfit.

*DeLaurentiis's biographers, while acknowledging Korshak's role, claim that the meeting took place over dinner at Bluhdorn's office. (Kezich and Levantesi, Dino, 218) tThe deleted producer is most definitely Dino DeLaurentiis.

* Interestingly, the agency source of the above memo is deleted, which usually implies CIA. The memo contains fifty-two more pages, currently withheld for review by that other agency. One guess is that it involves CIA investigations of laundered Mafia money coming from Italy.

^The Brink's Job was based on a true story that occurred in 1950. The period piece was shot in the North End of Boston, which was at the time dominated by Italians and Irish, and problems first arose when residents refused to take their TV antennas down, even for a few hours—television antennas did not exist in 1950. Universal production chief Ned Tanen called Lew Wasserman, who in turn called the Fixer. Two hours later, Tanen received a call from the unit producer. "You want to see something funny? You ought to see these 280-pound Italian women climbing up on their roofs, tromping around in their black skirts and work boots, ripping out their TV aerials." As Tanen later noted, "Now there's nothing dishonest about that. But Lew had called his good friend Sidney, and they had got it done." The film received an Oscar for set decoration—although it is doubtful that Korshak ever received a statuette. (Sharp, Mr. and Mrs. Hollywood, 351-53)

*Just above his signature, the form reads, "False statements made knowingly and willfully in passport applications or other supporting documents are punishable by fine and/or imprisonment under the provisions of 18 USC 1001."