Chapter 13

Pasture Management

Whether your cow is on a total grazing program or you wish only to optimize a small pasture area, many of the same principles apply.

If you have a grazing area of even one acre it is possible, with active management, to provide the major portion of your cow’s livelihood for as many months as the grass will grow. A good regular soaking with a sprinkling system will greatly extend the grazing. As noted earlier, the ideal grass length is four to seven inches. Dividing the field with electric fence until the cow has eaten about two-thirds of the grass in her assigned area is best. Then you can mow it before seed heads form and it gets stemmy. Many species of grass will come back thicker than before.

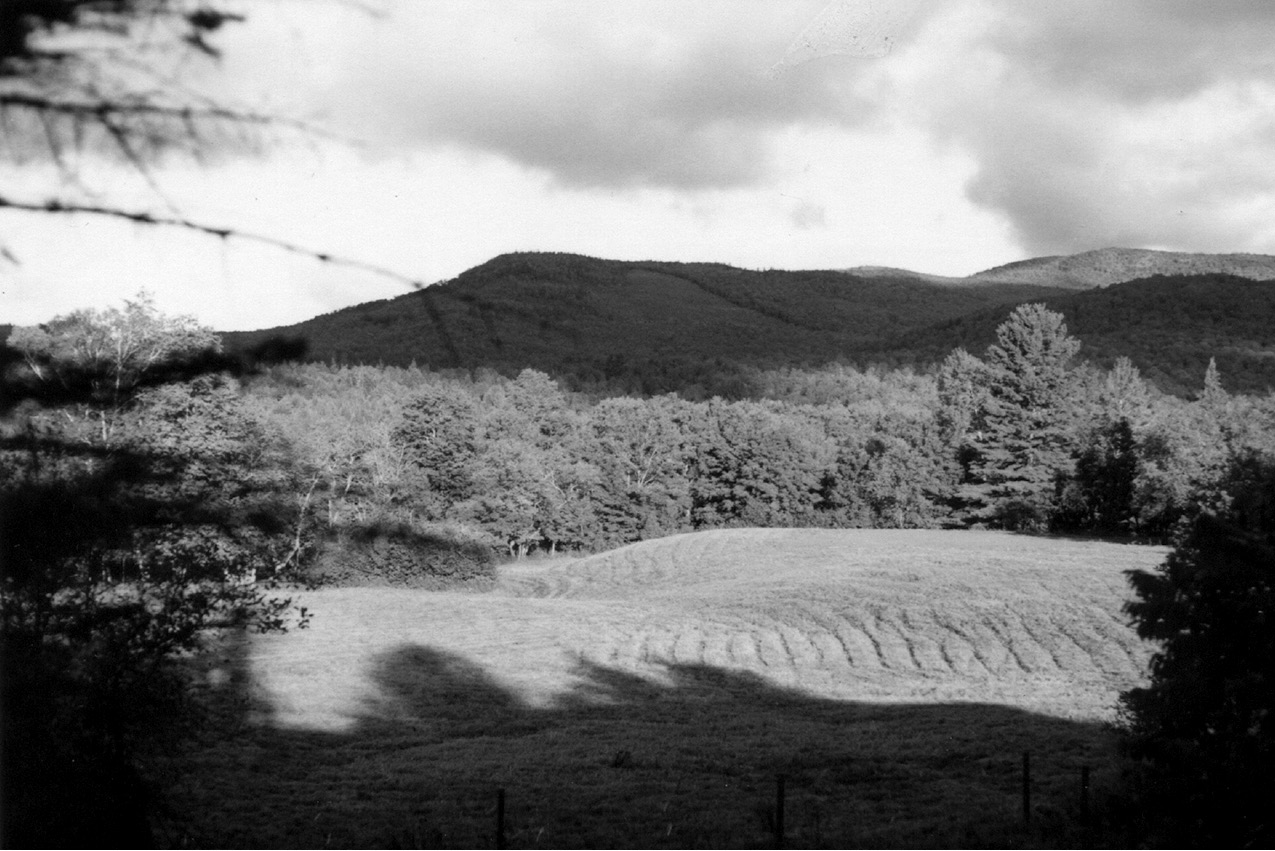

Coburn Farm, pasture home of my cows Clarinda and Helen

Photograph courtesy of Joann S. Grohman

• • • •

Mowing

Mowing improves the grazing in a pasture almost immediately. If seed heads have already formed, oddly enough, for a couple of days a cow will often eat that headed-up grass after it is mowed, even though she ignored the standing crop. A mowed field gets busy and grows again as soon as it gets watered or rained on. But it grows back faster if mowed before seed heads are fully formed. Like any plant, the ambition of grass is to propagate; once heads have fully formed it takes it a while to get back in the mood to start over.

Use a brush hog, reel mower, sickle-bar mower, or a mower-conditioner (“haybine”). Do not use a rotary or flail mower on a pasture as it throws the cow pats all around. Left undisturbed, the pats form what parasitologists call a “circle of repugnance.” The grass around each undisturbed pat will form a bright green hummock that a cow will ignore until the third year, thus avoiding reingesting parasites. This results in the characteristically hummocky appearance of cow pastures in long use. If you prefer your ground to stay flat and you have enough pasture so that you can afford to fence your cow off part of the land in a three-year rotation, brush-hogging will smooth it out. Brush-hogging has other benefits as well. It discourages perennial weeds (as does mowing), and it gets rid of tree seedlings that are always trying to reclaim the land around my place.

Another fine option for cleaning the land is to run poultry on it. The “chicken tractor” concept is highly effective. A little chicken hut with a fence framed around it like a big playpen can be dragged forward daily to the benefit of all. No parasite survives the busy hen. Even simpler, allow the chickens to free-range. My self-renewing flock of about fifty assorted birds has kept the nearby acres free of all sorts of annoyances. I have not seen a tick in years. They keep down flies too.

• • • •

Weeds

There are few perennial weeds that a cow will eat. A great many of them are toxic or have stickers. Tree saplings are a curse.

A method of weed and sapling control that also promotes optimal pasture utilization, once common and now being revived, is to keep mixed species of animals. Cattle, goats, sheep, pigs, and poultry can all share the same pasture if desired, so you can consider that for the future. They have differing tastes in herbage and are host to different parasites, and their droppings contain different nutrients, too.

There are some plants that no animal will eat. These include goldenrod and buttercup.

Mowing broadleaf plants before seed heads form will eventually exhaust them without recourse to herbicides. But the presence of some forbs is desirable. Some provide nutrients otherwise low in grass and may even be sought by your cow. It has been found that many forbs foster more efficient rumen fermentation, with the result that less methane is produced. Nonetheless, a large weed population is indicative of low fertility. This pasture needs feeding.

• • • •

Pasture Improvement

You will wish to take some measures to encourage good grass and discourage weeds. Almost any grass is good and doubtless will support a cow. Whatever came up in your pasture is what likes to grow in your neighborhood. Many fine grasses can be seeded to provide balance and variety, but go slow on special mixtures. Often they embody more theory than practice.

There are some pasture grass problems for which we all need to be on the alert. Extension Service recommendations for seeding of new grass varieties over past decades has resulted in introduction of exotic species. It takes experience to recognize the various species of grass. If there are farmers in your area, find one and ask him or her if there are undesirable grasses for which you need to be on the lookout. The Extension Service has free educational materials on grasses.

Fescue is a grass introduced to the United States from New Zealand. When tall, it may contain toxic amounts of an endophytic mold. Tall fescue is unpalatable but drought resistant and may be the only forage left standing.

Johnson grass, arrow grass, Sudan grass, and common sorghum are all capable of causing cyanide poisoning under certain circumstances. Stress to these plants increases toxicity; drought, trampling, and freezing are common stresses. Nitrogen fertilizers and spraying with herbicides also increase toxicity. All types of wild cherry carry the threat of cyanide poisoning, but cattle avoid wild cherry unless nothing else is available. My fields are surrounded by it, and none of my animals ever touches it.

Sweet clover, as hay or silage, that becomes spoiled may contain toxic levels of dicoumerol, a blood-thinning agent induced by a mold. This is not a problem when grazing fresh clover.

Bracken fern is seriously toxic. Cattle do not eat it if other forage is available, but it may get mowed along with hay. It does not lose its toxicity in storage and may be difficult for a cow to avoid in her manger. If bracken or other questionable weeds have been baled into your hay, fluffing up the flakes of baled hay will make it much easier for your cow to skip over what she doesn’t fancy.

Wild cherry, bracken fern, and other toxic plants are to be avoided. But the grasses remain important forage despite the problems they may present under certain conditions of climate or stage of growth. Cattle not stressed by hunger are remarkably good at avoiding toxic plants.

If your field is not too rocky or remote for heavy equipment, grass seed can be direct-seeded by slicing into the turf without plowing it up. This requires special equipment, but in many areas this work can be contracted for. Your extension agent may recommend this procedure, but keep in mind: he or she did not go to school to learn how to tell you to do nothing. Neither does your agricultural supply store have anything to be gained by leaving your field alone. Certainly don’t buy seed before soil testing. Soil amendments, or a dose of some nutrient, may be all that is necessary to permit the grass species you already have to compete successfully against the weeds. You may just need to add more water. An oscillating lawn sprinkler often does wonders.

Mowing and leaving the grass as mulch, plus the manure left by grazing animals, will help keep pasture in good heart. A layer of snow each winter adds nitrogen. All the same, a cow is taking away the nutrients she uses to make milk, and more. Plan to periodically add back fertility by spreading manure and lime. A yearly soil test and consultation with experts in your state will soon make you an expert too.

• • • •

Maintaining Pasture

Once established, your pasture needs to be kept mowed or grazed and fertilized in order to be permanent. It will not die unless there is severe drought or overgrazing. Freezing may occasionally damage it but, if you have native grasses, seldom seriously. Native grasses are adapted to prevailing climatic conditions.

If you are faced with a barren, plowed-up waste, you will then almost certainly have to seed it; otherwise it will be colonized by weeds. If it formerly had a broad-leaf crop on it, it may even have been treated with an herbicide specific to grass. You could then investigate the reputation of alfalfa in your neighborhood. Being a broad-leafed plant, it would not have been affected. If the land formerly had corn on it (corn is a grass), a broad-leaf herbicide may have been used, in which case the clover contained in most grass mixtures will not grow, nor would alfalfa.

If you are planting either alfalfa or clover, remember that these two fine legumes can cause bloat. If this is to be your cow’s only pasture, you will need to plan on buying some hay to feed your cow before she goes out in the morning, which means keeping her in at night.

If you are contending with a plowed-up area, this means it is accessible to heavy equipment. It may be easiest to contract out the necessary disking and seeding. If you must proceed from a standing start, a balanced chemical fertilizer may be your best option, unless you have time to get in rye and then plow it under as green manure. Because of the drastic decline in farming, you may be unable to find equipment, labor, or real animal manure with which to fertilize. This might be a good time to try fertilizing with milk (see here).

When you are seeking advice on choice of seed, make it clear whether the land is to be used for grazing, hay, or both; mixtures are designed for each use. Even so-called permanent pasture will benefit from reseeding about every four years if you are not satisfied with what is coming up by itself.

Keep the cow off the part you intend for hay, or there will be dung in the hay and trampled spots. A hay field comes up every year just like pasture or lawn. If you don’t fertilize it, you will get a little less every year. In the fall spread lime if needed, hen dressing, or just about anything you can find to augment your own cow’s supply.

• • • •

Comfrey

Comfrey is a perennial leafy plant with deep taproots. It is hardy and is widely fed to cows in Russia. It contains as much as 24 percent protein and is rich in calcium and other nutrients. In favorable conditions it grows prolifically. Over the past hundred years it has fallen in and out of favor as feed. Its detractors note that it contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids capable of causing liver damage when consumed in large quantities. To put things in perspective, this same anti-nutrient is found at approximately the same levels in spinach and chard.

There exists some confusion as to which cultivar deserves the Latin name Symphytum officinale L. The kind I have fits the description of Russian comfrey. It exhibits lush, dense growth and easily crowds out competitors. It propagates by both seeds and roots. By the third year the taproot may be three inches in diameter and over three feet long. It is brittle and will break if pulled, soon to be sending up new shoots from the fragments. It also sends out a lateral root or arm that claims new ground. It grows three or more feet tall and has a fuzzy stem with small, pretty blue flowers and rough leaves. If you plant it you need to be pretty sure you want it. It took me several years to stop fighting it and learn to love it. Once they have developed a taste for it, my cows, if seeing me in the garden, will hurry from across the pasture in hopes I will cut an armful for them. As forage it is said to be possible to feed comfrey for up to 10 percent of a cow’s roughage. I have attempted to dry it for winter use, but it shatters hopelessly. It would need to be bagged.

Comfrey has an impressive ability to improve soil. If you succeed in reclaiming its ground either by hand-digging or by solarization (covering it with a tarp and letting the sun cook it to submission), the new ground is light and wonderfully fertile.

As a healing herb comfrey has few equals. I make a slurry of it to rub on an inflamed udder or any type of wound or injury, bovine or human.

• • • •

Woodland Grazing

If all you have is woodland, you can put your cow right into that. She can help you clear land by eating all the small stuff and the tops of suitable deciduous trees such as willow and alder. Once the land is opened to the sun, grass will come up by itself and stumps will slowly rot away. This is what the early settlers did when they had no fields. They couldn’t go out and buy bales of hay to augment a cow’s diet as we are able to.

In colonial times hay was so dear that salt marshes were intensely sought after. They are natural stands of grass and totally free of weeds; colonial plats show salt marshes crosshatched with lines attesting to the importance of ownership of holdings as small as a quarter of an acre.

Milk production will be poor if a cow has nothing but woodland in which to make a living. You will need to bring her some hay. If you do this at fixed times she will wait for it, eat it, leave, and get back to work in the woods.

Woodland grazing carries inherent risks, among which is the possibility that in the absence of grass a cow may ingest poisonous plants. Some of the most common are as follows.

Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum), Water Hemlock (Cicuta douglasii and Oenanthe crocata)

Throughout the Northeast, poison hemlock and water hemlock are a hazard to cattle grazing in damp places in woodlands or along their edges. Best to learn to recognize these and similar plants and try to either eradicate them or fence them off. Both poison hemlock and water hemlock resemble carrot tops and Queen Anne’s lace. Water hemlock is the most violently toxic plant in the United States. It is adapted to moist sites, grows two to three feet high, and is palatable. Poison hemlock may grow ten to twelve feet high. It is unpalatable, and cattle are unlikely to eat it unless other green forage is unavailable.

White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima)

This plant greatly resembles the garden plant ageratum. The flowers are small, white, and fluffy. It is found primarily in the Midwest, growing one to three feet tall. It is primarily a woodland plant but persists in cleared areas. It is best eradicated by pulling it up. Cattle should be fenced away from areas where it is found. Early symptoms of poisoning include trembling and loss of appetite. One large dose of the plant may produce poisoning. It also has a cumulative effect, so that persistent small amounts are equally dangerous. The milk of affected animals can be fatal to calves, lambs, and humans. Meat from poisoned animals is also toxic.

White snakeroot poisoning is relatively rare, but any cow owner should learn to recognize the plant as its range may be spreading.

For a comprehensive listing with full descriptions of poisonous plants, see the website of the USDA Agricultural Research Service.

• • • •

Predators

Unlike goats and sheep, a cow is rarely attacked by predators, but bring her in during hunting season. Packs of domestic dogs are a threat to all livestock. Although most of my animal-keeping experience has been adjacent to huge forests, it is only to dogs that I have lost livestock.

Keep a bell on your cow, especially if she has access to woodland. Then you will always know where she is. Should she be chased, her bell may alert you.