After Chapter 6.1, you will be able to:

When you look in the mirror, whom do you see? If you’re studying to take the MCAT, chances are some descriptors that come to mind include student, intelligent, future doctor, and so on. Our own internal list of answers to the question Who am I? form our self-concept. Many of the ways in which we define ourselves fall under the classification of a self-schema; that is, a self-given label that carries with it a set of qualities. For example, the athlete self-schema usually carries the qualities of youth, physical fitness, and dressing and acting in certain ways, although these qualities may change depending on culture, socioeconomic status, and personal beliefs. The idea of self-concept goes beyond these self-schemata; it also includes our appraisal of who we used to be and who we will become: our past and future selves.

Sometimes the terms self-concept and identity are used interchangeably, but psychologists generally use them to refer to two different but closely related ideas. Social scientists define identity as the individual components of our self-concept related to the groups to which we belong. Whereas we have one all-encompassing self-concept, we have multiple identities that define who we are and how we should behave within any given context. Religious affiliation, sexual orientation, personal relationships, and membership in social groups are just a few of the identities that sum to create our self-concept. In fact, our individual identities do not always need to be compatible. Are you the same person when interacting with your friends as you are when you interact with coworkers or family? For most people the answer is no; they take on particular identities in different social situations.

While there are many different types of identity, the MCAT—for historical or social reasons—tends to focus on some forms of identity more than others.

Gender identity describes a person’s appraisal of him- or herself on scales of masculinity and femininity. While these concepts were long thought to be two extremes on a single continuum, theorists have reasoned that they must be two separate dimensions because individuals can achieve high scores on scales of both masculinity and femininity. Androgyny is defined as the state of being simultaneously very masculine and very feminine, while those who achieve low scores on both scales are referred to as undifferentiated. Gender identity is usually well established by age three, although it may morph and change over time. Some theories, such as the theory of gender schema, hold that key components of gender identity are transmitted through cultural and societal means.

Transgender individuals, for whom gender identity does not match biological sex, have been a heavily stigmatized group in American culture. In fact, it was not until the publication of the DSM-5 in 2013 that gender identity disorder was formally removed as a diagnosis. The DSM-5 includes the diagnosis gender dysphoria, which is given only to individuals for whom gender identity causes significant psychological stress.

Keep in mind that gender identity is not necessarily tied to biological sex or sexual orientation, although in most Western cultures these concepts are seen as closely related. While it is typical of most cultures to view gender as a strictly binary concept, many cultures consider a third gender. For example, the people of Samoa refer to androgynous but biologically male individuals as fa’afafine. To the Samoans, the fa’afafine are seen as an important social caste and are accepted as equals, although this is not always the case for third genders across all cultures.

Ethnic identity refers to one’s ethnic group, in which members typically share a common ancestry, cultural heritage, and language. Many social psychologists study the ways in which our ethnic identity influences our perspectives of ourselves. In a 1947 study, Kenneth and Mamie Clark explored ethnic self-concepts among ethnically white and black children using a doll preference task: the experimenter showed each child a black doll and a white doll and asked the child a series of questions about how the child felt about the dolls. The majority of both white and black children preferred the white doll. This study was important because it highlighted the negative effects of racism and minority group status on the self-concept of black children at the time. However, subsequent research using improved methodology (for example, randomizing the ethnicity of the experimenter), has shown that black children hold more positive views of their own ethnicity; this may also represent societal changes at large.

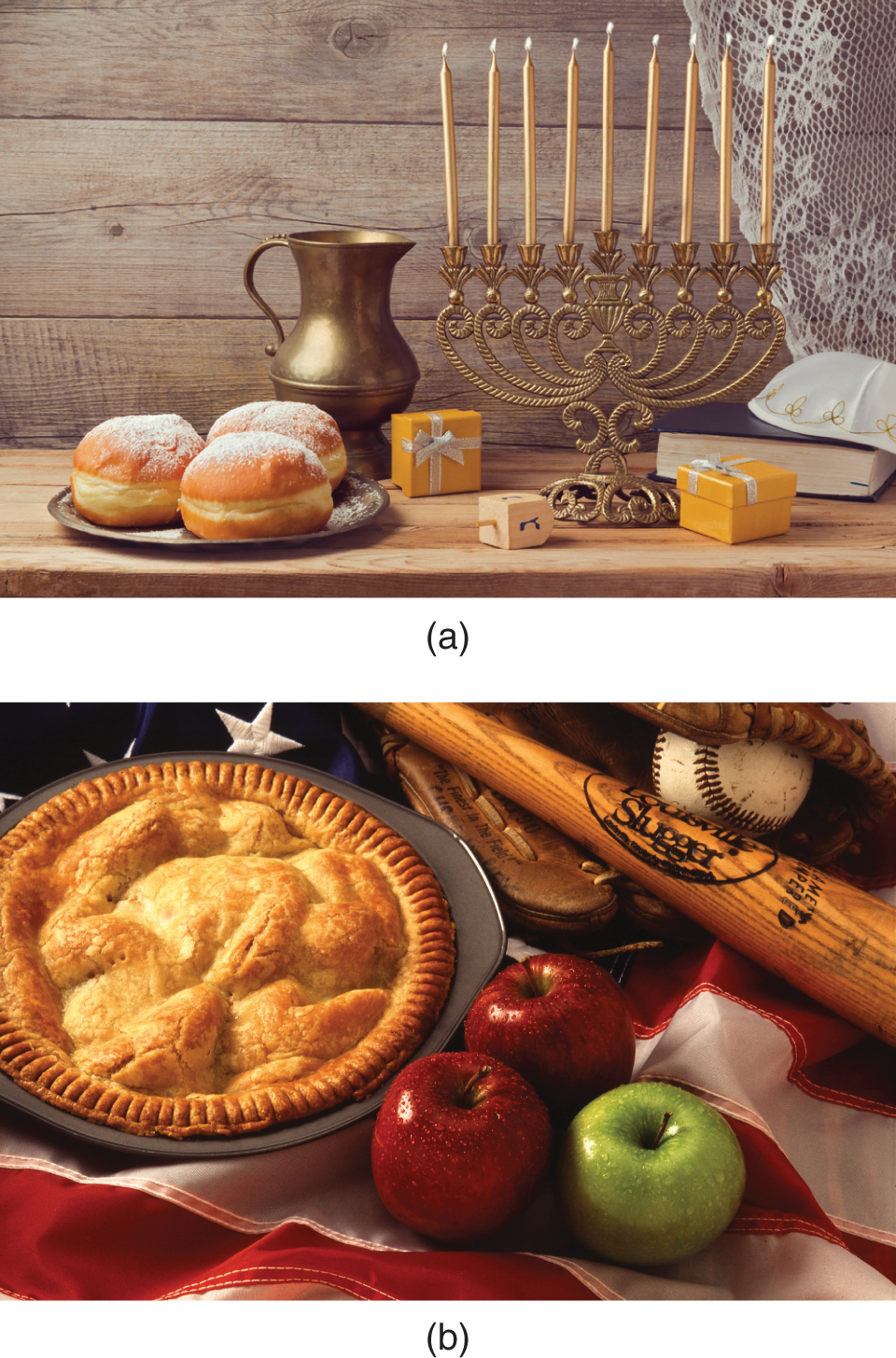

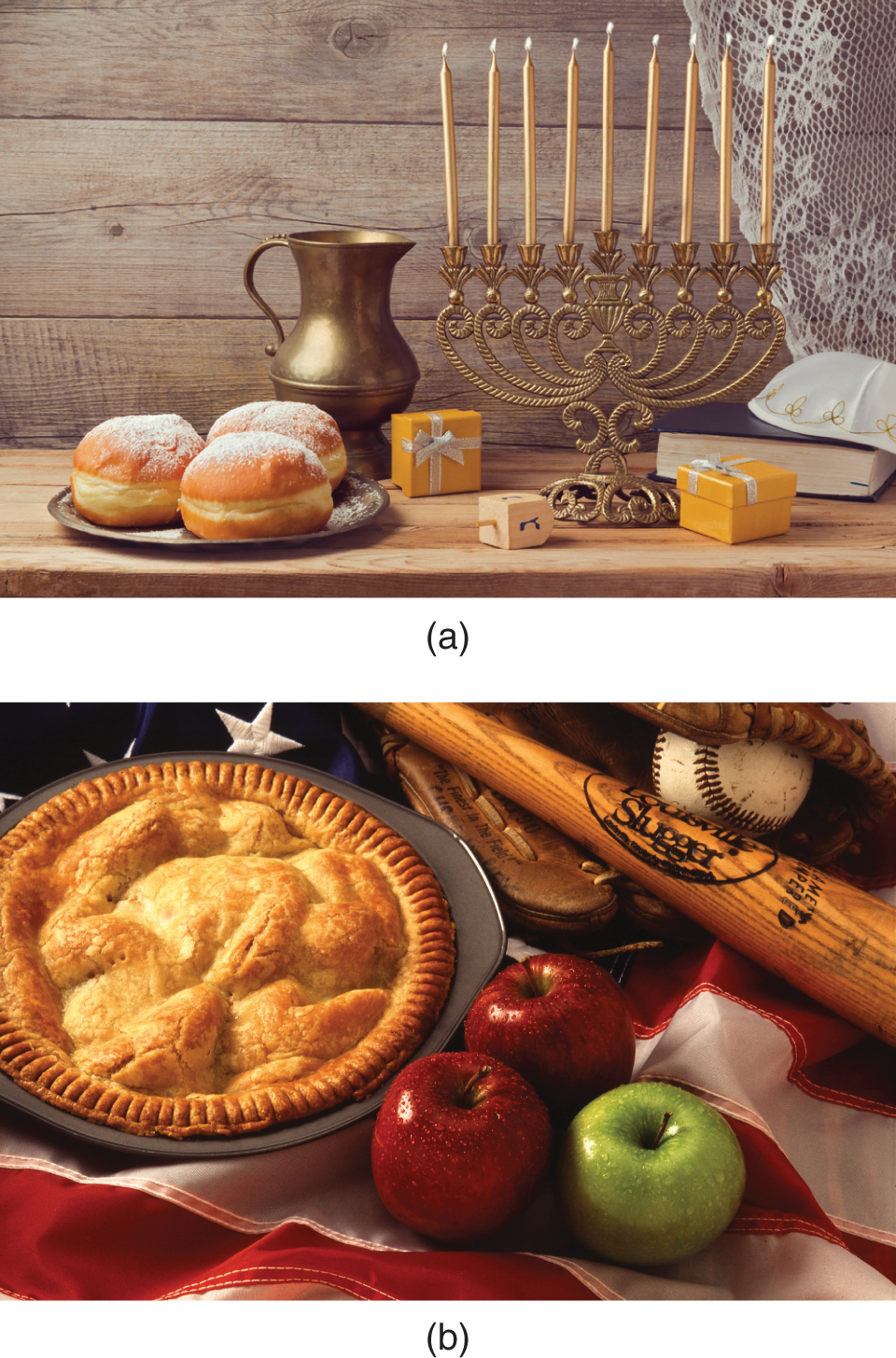

While ethnicity is largely an identity into which we are born, nationality is based on political borders. National identity is the result of shared history, media, cuisine, and national symbols such as a country’s flag. Nationality need not be tied to one’s ethnicity or even to legal citizenship. Symbols play an important role in both ethnic and national identity: symbols of Jewish ethnicity are shown in Figure 6.1a, while symbols of American nationality are shown in Figure 6.1b.

Of course, there are many more categories through which we evaluate our identity. We compare ourselves to others in terms of age, class, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, and so on. Aspects of these other identities are explored in other parts of MCAT Behavioral Sciences Review.

It is important to know that there are several factors that determine which identity will be enacted in particular situations. It is believed that our identities are organized according to a hierarchy of salience, such that we let the situation dictate which identity holds the most importance for us at any given moment. For instance, male and female college students in same-sex groups are less likely to list gender in their self-descriptions than students in mixed-gender groups. Furthermore, researchers have found that the more salient the identity, the more we conform to the role expectations of the identities. Salience is determined by a number of factors, including the amount of work we have invested into the identity, the rewards and gratification associated with the identity, and the amount of self-esteem we have associated with the identity.

Our individual self-concept plays a very important role in the way we evaluate and feel about ourselves. Self-discrepancy theory maintains that each of us has three selves. Our self-concept makes up our actual self, the way we see ourselves as we currently are. Our ideal self is the person we would like to be, and our ought self is our representation of the way others think we should be. Generally, the closer these three selves are to one another, the higher our self-esteem or self-worth will be.

Remember that esteem is one of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (#4 in priority). This model is discussed in Chapter 5 of MCAT Behavioral Sciences Review.

Those with low self-esteem don’t necessarily view themselves as worthless, but they will be far more critical of themselves. As a result, they take criticism from others poorly and typically believe that people will only accept them if they are successful. Research also shows that they are more likely to use drugs, to be pessimistic, and to give up when facing frustration than their counterparts with high self-esteem.

While self-esteem is the measure of how we feel about ourselves, self-efficacy is our belief in our ability to succeed. Self-efficacy can vary by activity for individuals; we all can think of situations in which we hold the belief that we are able to be effective and, conversely, those in which we feel powerless. Of course, we are more motivated to pursue those tasks for which our self-efficacy is high, but we can get into trouble when it is too high. Overconfidence can lead us to take on tasks for which we are not ready, leading to frustration, humiliation, or sometimes even personal injury. Self-efficacy can also be depressed past the point of recovery. In one study (which certainly could not be replicated under current ethical guidelines), dogs were divided into three groups. The first was a control group in which the dogs were simply strapped into a harness. In the second group, dogs were similarly strapped into a harness but subjected to painful electrical shocks, which they could stop by pressing a lever. Dogs in the third group were similarly harnessed and shocked, but were powerless to control the administration of the shock. Dogs in the first two groups recovered from the experience quickly; the third group soon stopped trying to escape the shock and acted as if they were helpless to avoid the pain of the experience, even when offered opportunities to avoid being shocked. Only when the dogs were forcibly removed from their cages did they change their expectations about their control over the electrical shocks and took action to escape their predicament. This phenomenon is called learned helplessness and is considered one possible model of clinical depression.

Locus of control is another core self-evaluation that is closely related to self-concept. Locus of control refers to the way we characterize the influences in our lives. People with an internal locus of control view themselves as controlling their own fate, whereas those with an external locus of control feel that the events in their lives are caused by luck or outside influences. For example, a runner who loses a race may attribute the cause of the loss internally (I didn’t train hard enough) or externally (My shoes didn’t fit and the track was wet).

Locus of control and cognitive dissonance are integral to attribution theory. In order to preserve self-esteem, we often see our successes as a direct result of our efforts and our failures as the result of uncontrollable outside influences. Attribution theory is discussed in Chapter 10 of MCAT Behavioral Sciences Review.

All of these ideas work hand-in-hand to influence the way we feel about ourselves. The happiest among us are those who have high self-esteem, view themselves as effective people, feel that they are in control of their destinies, and see themselves as living up to their own expectations of who they would like to be.

Effective MCAT students review full-length exams with an internal locus of control: What can I do to prepare myself better for the next practice test? An external locus of control prevents students from actually gaining anything from their practice: Oh, that was just a stupid question.