After Chapter 11.3, you will be able to:

Demographics refer to the statistics of populations and are the mathematical applications of sociology. Demographics can be gathered informally, such as a professor asking how many freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors are in a given course, or may be gathered formally. For example, the United States Census Bureau gathers full demographic data about every individual in the country every ten years.

Demographers can classify individuals based on hundreds of different criteria. The MCAT will not expect you to know advanced topics within demographics, but familiarity with some of the common demographic categories is important. In this section, we’ll explore age, gender, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, and immigration status.

Many sociologists document a “graying of America” as the Baby Boomer generation ages. Over 70 million Americans will be 65 or older by 2030, representing nearly 20 percent of the population. The fastest-growing age cohort in the United States is the 85-or-older group. This has profound effects on healthcare: more than 40 percent of adult patients in acute care hospital beds are 65 or older.

Ageism is prejudice or discrimination on the basis of a person’s age. This can be seen at all ages. For example, young professionals entering the workplace are often viewed as being inexperienced, and their opinions and ideas may therefore be ignored or downplayed. Older individuals may be perceived as frail, vulnerable, or less intelligent, and may thus be treated with less respect.

Gender is a social construct that corresponds to the behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with a biological sex. Gender differences tend to emphasize the distinct roles and behaviors of men and women in a given culture, which is influenced by cultural norms and values. Differences between genders do not necessarily imply inequity, although it occurs in many cultures. Gender inequality, however, is the intentional or unintentional empowerment of one gender to the detriment of the other. Gender segregation, on the other hand, is the separation of individuals based on perceived gender. This includes division into male, female, and gender-neutral bathrooms; separating male and female sports teams; and establishment of single-sex schools.

Note that sex and gender are not synonymous terms. Sex is biologically determined; an XY genotype corresponds to male sex, and an XX genotype corresponds to female sex. Gender relates to a set of behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits. In most cultures, there are two genders: male and female. However, some cultures consider more than two genders, and some individuals’ gender identities do not match their biological sex.

Race is a social construct based on phenotypic differences between groups of people. These may be either real or perceived differences. It is notable that race is not strictly defined by genetics, but rather classifies individuals based on superficial traits such as skin color. Racialization refers to the definition or establishment of a group as a particular race; for example, while Judaism was historically viewed only as a religion, the concept of a Jewish race has become more prevalent over the last century. Even then, the definition features of a given race are not static. Racial formation theory posits that racial identity is fluid and dependent on concurrent political, economic, and social factors.

Certain racial and ethnic groups have a higher incidence of specific health problems. For example, the Chinese population accounts for a disproportionate number of chronic hepatitis B infections and liver cancer. Mediterranean and African populations have a significantly higher rate of hemoglobinopathies (diseases related to hemoglobin). Ashkenazi Jews have a higher rate of autoimmune diseases. Certain Native American populations are associated with gallbladder and biliary tree diseases. Being of a particular race or ethnicity is not necessary for the development of any disease, but may certainly be associated with increased risk.

Ethnicity is also a social construct, which sorts people by cultural factors, including language, nationality, religion, and other factors. The distinction between race and ethnicity can be important because one can choose whether or not to display ethnic identity, while racial identities are always on display. For example, a person could be considered black due to physical characteristics; however, this same person’s ethnicity could be Latino, African, African American, or a number of other ethnic identities.

Symbolic ethnicity describes a specific connection to one’s ethnicity in which ethnic symbols and identity remain important, even when ethnic identity does not play a significant role in everyday life. For example, many Irish Americans in the United States celebrate “Irishness” only one day per year: St. Patrick’s Day. In all other facets of life, these individuals’ Irish-American ethnicity does not play a significant role. Other examples include attending folk festivals, visiting specific cultural locales for holidays, or participating in an ethnic pride rally.

It is important to consider how race and ethnicity may affect one’s ability to receive proper health care. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a government agency, reports that race and ethnicity influence a patient’s chance of receiving many specific procedures and treatments. Whether due to conscious or unconscious bias, there is evidence that different races are not always offered the same level of care escalation in a medical emergency.

Many public health outreach efforts are aimed at closing the gap in health disparities between populations. Health and healthcare disparities are discussed in Chapter 12 of MCAT Behavioral Sciences Review.

On the other hand, there are a number of public health outreach projects that target at-risk racial or ethnic populations through education, screening, and treatment. These specific strategies are geared to close gaps in health disparities. Many large university health systems run free clinics in local neighborhoods and may target specific populations; for example, some of these clinics will staff Spanish-speaking doctors and medical students to cater to the Hispanic immigrant population.

Sexual orientation can be defined as the direction of one’s sexual interest toward members of the same, opposite, or both sexes. It is generally divided into three categories:

Sexual orientation involves a person’s sexual feelings and may or may not be a significant contributor to that person’s sense of identity. It may or may not be evident in the person’s appearance or behavior. Disclosure of minority sexual orientations, sometimes called coming out of the closet, is a major milestone in the absorption of sexuality into one’s identity. This has also been shown to have therapeutic effects: coming out is associated with decreases in depressive and anxious symptoms that can even be measured physiologically as cortisol levels drop during this time.

Human sexuality continues to be an important area of research for psychologists, sociologists, and biologists alike, but evidence shows that sexuality is likely more fluid than previously believed. Alfred Kinsey was a pioneer in this area, and—in addition to a number of other models and publications—described sexuality on a zero to six scale, with zero representing exclusive heterosexuality and six representing exclusive homosexuality. When ranked on this Kinsey scale, few people actually fell into the categories of zero and six, with a significant proportion of the population falling somewhere between the two.

Sexual and gender identity minorities are often grouped together under the umbrella term LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender). In some cases, this acronym has been expanded to include other self-definitions of sexuality and sexual identity, including Q (queer or questioning), I (intersex), or A (asexual).

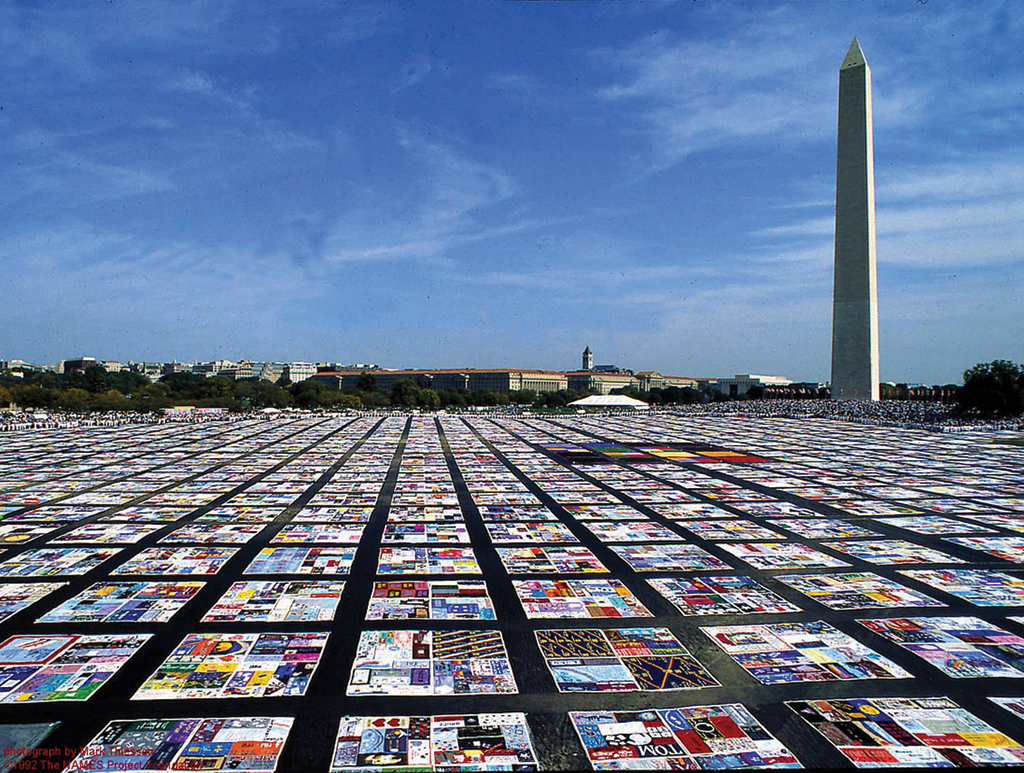

Several health disparities have been recognized within the LGBT community. The most significant historical disparity is HIV, which disproportionately affected gay men in urban environments during the early 1980s. While the prevalence of HIV is still slightly higher in men who have sex with men (MSM), it exists in all populations. Efforts to encourage safe sex and increase screening have helped slow the epidemic of HIV, as has increased awareness of those with HIV/AIDS with projects like the AIDS Memorial Quilt, shown in Figure 11.6. Within the healthcare system, lesbians receive less screening for cervical cancer and may not be screened for other sexually transmitted infections. Transgender individuals have multiple areas of increased risk, including use of “street hormones” without proper counseling on their side effects.

Mental health disparities are also common in the LGBT community. LGBT youth are at significantly higher risk for bullying, victimization, and violence, and have higher rates of suicide. In adults, the LGBT population has a higher prevalence of depression and anxiety than their heterosexual counterparts; gay men have an increased rate of eating disorders as compared to heterosexual men. A host of campaigns and outreach efforts have begun to target these disparities.

According to the Census Bureau, the nation’s total immigrant population is growing rapidly; it was quantified at 40.4 million in 2011 and is expected to increase by roughly 20 million in the next two decades. This tells us that immigrants, whether documented or undocumented, are interwoven into every social structure and institution in the United States and make up a significant demographic bloc. The nativity of immigrant populations changes over time; in the most recent census, the largest proportions of immigrants had emigrated from Mexico, the Caribbean, and India.

Considering the number of immigrants, there are often barriers that affect interactions with social structures and institutions. The complex organization of the United States healthcare system is starkly different from those of most other nations, and this may present a barrier to understanding for immigrants. Language barriers may also make it difficult for immigrants to access healthcare or to take control of their healthcare decisions; telephone translation services have been created to help facilitate the conversation between clinician and patient. Racial and ethnic identity may be more pronounced in first-generation immigrants, and the same biases and prejudices against certain racial and ethnic minorities might be compounded by the individual’s immigrant status; this interplay between multiple demographic factors—especially when it leads to discrimination or oppression—is termed intersectionality. Finally, undocumented status presents a major barrier for many immigrants to access healthcare for fear of reporting and deportation.

Since 1950, the United States population has roughly doubled. In addition to increasing in size, the makeup of the American population has changed significantly. The average age in the United States has increased, and the population is continuing to become more racially and ethnically diverse. These are examples of demographic shifts: changes in the makeup of a population over time.

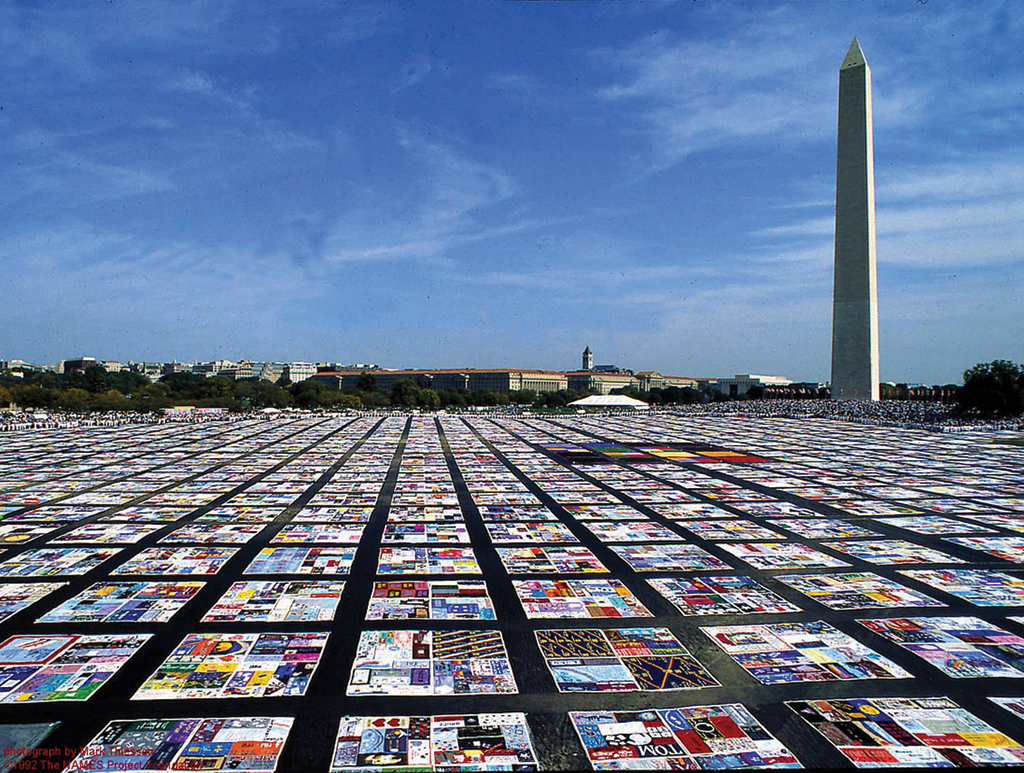

Population projections attempt to predict changes in population size over time, and can be assisted by historical measures of growth, understanding of changes in social structure, and analysis of other demographic information. In this last category, population pyramids provide a histogram of the population size of various age cohorts, as shown in Figure 11.7.

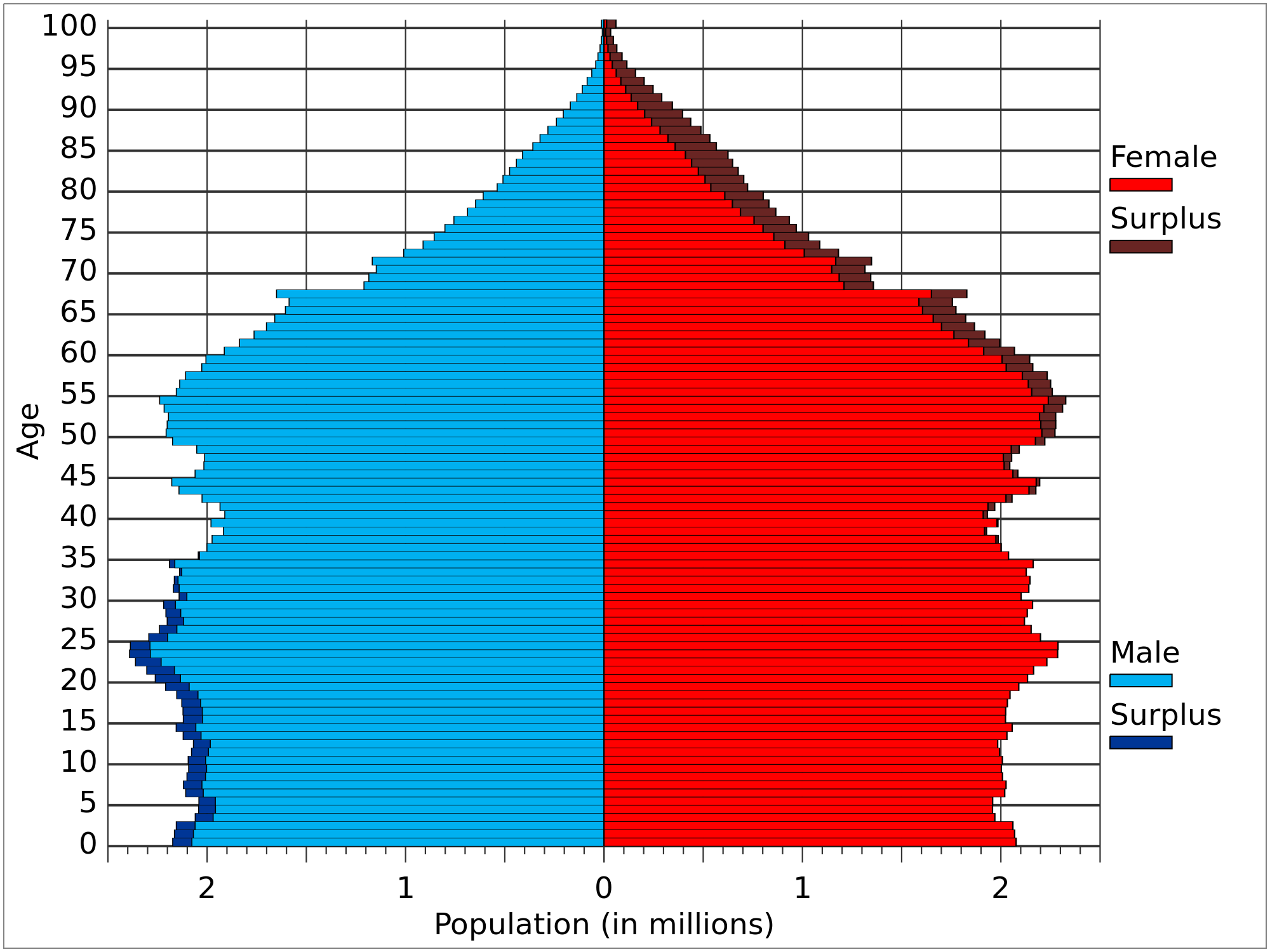

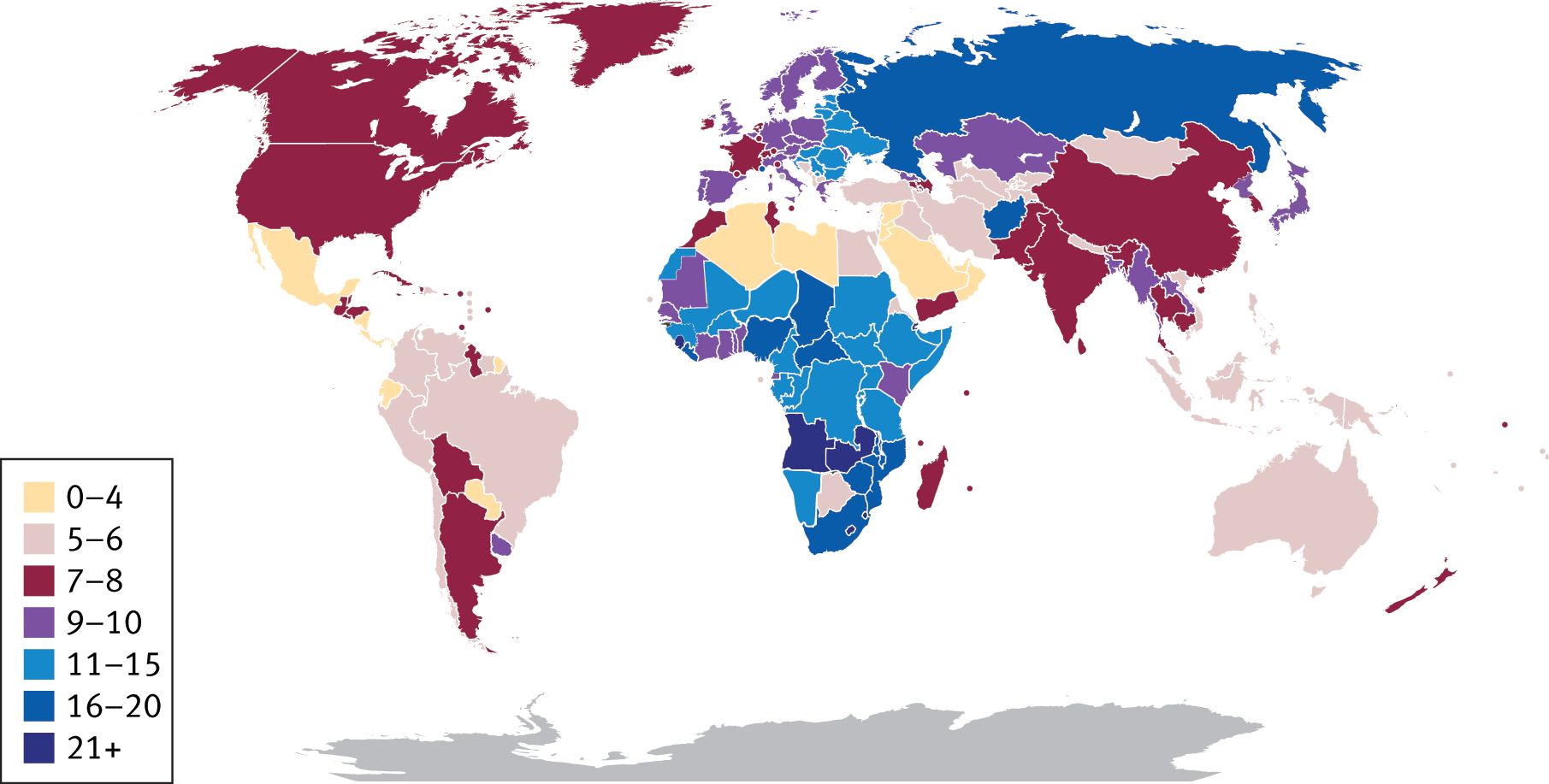

The increased population of the United States is due to a number of factors that center around fertility, mortality, and migration. Fertility rate refers to the average number of children born to a woman during her lifetime in a population. In many parts of the world, fertility rate is the primary driver of population expansion; for example, in many parts of Africa, the average fertility rate is between four and eight children per woman, as seen in Figure 11.8. In the United States, fertility rates have trended downward over time; in 2013, the rate was still above two, indicating that fertility rates were still contributing to population growth.

Demographic statistics:

Mortality rates refer to the number of deaths in a population per unit time. Usually, this is measured in deaths per 1000 people per year. With advancements in healthcare and access, the mortality rate in the United States has dropped significantly over the past century. However, mortality rates are a significant brake on population growth in many parts of the world, as demonstrated in Figure 11.9. The decreased mortality rate in the United States is one contributor to the increase in average age of the population, as is a decreased fertility rate. In addition, the aging of the baby boomer generation, one of the largest generations in United States history, increases this average age. Both birth and mortality rates can be reported in multiple forms: the total rate for a population, the crude rate (adjusted to a certain population size over a specific period of time and multiplied by a constant to give a whole number), or age-specific rates.

Finally, migration is a contributor to population growth. Immigration is defined as movement into a new geographic space, whereas emigration is movement away from a geographic space. As described earlier, the United States continues to have larger net immigration than emigration, driving an increase in the population size. This also increases the racial and ethnic diversity of the United States, as do increased mobility within the country and increases in intermarriage between different races and ethnicities. Migration can be motivated by both pull factors, which are positive attributes of the new location that attract the immigrant, and push factors, which are negative attributes of the old location that encourage the immigrant to leave.

The United States population is getting bigger, older (average age has increased), and more diverse (through immigration, mobility, and intermarriage).

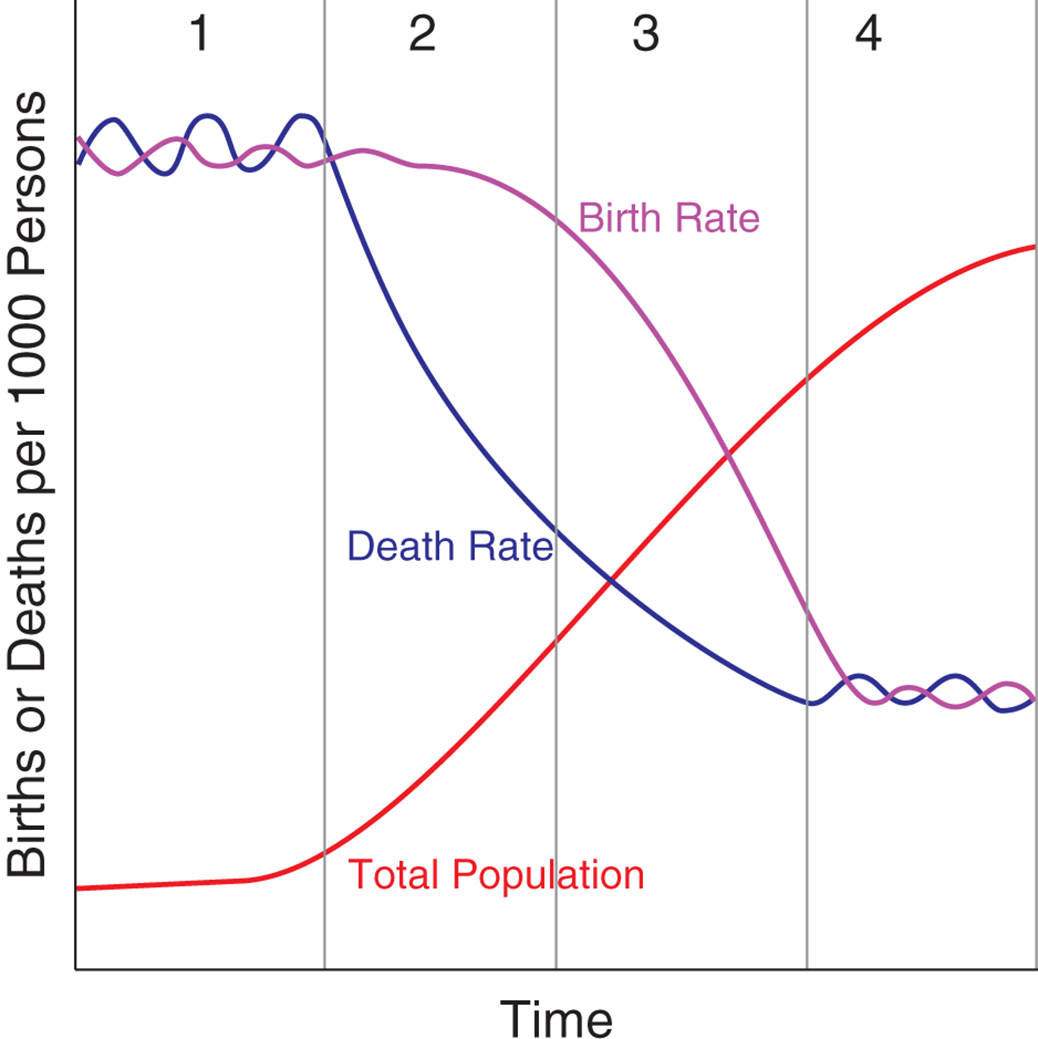

While demographic shift is a general term referring to changes in population makeup over time, demographic transition is a specific example of demographic shift referring to changes in birth and death rates in a country as it develops from a preindustrial to industrial economic system. This transition has been seen in the United States since the Industrial Revolution. Demographic transition can be divided into four stages:

A model of demographic transition can be seen in Figure 11.10.

During demographic transition, mortality rate drops before birth rate. Therefore, the population grows at first while mortality rate is dropping, and then plateaus as the birth rate decreases as well.

Malthusian theory focuses on how the exponential growth of a population can outpace growth of the food supply and lead to social degradation and disorder. A Malthusian catastrophe, then, is the prediction that as third-world nations industrialize and undergo demographic transition, the pace at which the world population will grow is much faster than the ability to generate food and mass starvation will occur. This is similar to the death phase of bacterial growth, when resources in the environment have been depleted, as described in Chapter 1 of MCAT Biology Review.

Social movements are organized either to promote or to resist social change. These movements are often motivated by perceived relative deprivation, or a decrease in resources, representation, or agency relative to the past or to the whole of society. Social movements that promote social change are termed proactive; those that resist social change are reactive. Members of social movements work to correct what they perceive as social injustices. Some examples of proactive movements include the civil rights movement, women’s rights movement, gay rights movement, animal rights movement, and environmentalism movement. Some examples of reactive movements include the white supremacist movement, counterculture movement, antiglobalization movement, and anti-immigration movement. To further their goals, social movements may establish coordinated organizations. For example, some organizations associated with the proactive movements above include the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Human Rights Campaign (HRC), The Humane Society, and Greenpeace. Social movements may also seek to share their message through the media and demonstrations. Political involvement is also common through lobbying and carefully directed donations.

Globalization is the process of integrating the global economy with free trade and the tapping of foreign markets. This is a relatively recent phenomenon spurred on by improvements in global communication technology and economic interdependence. Globalization leads to a decrease in the geographical constraints on social and cultural exchanges and can lead to both positive and negative effects. For example, the availability of foods (especially produce) from around the world during the entire calendar year can only be accomplished through trade with an extremely large number of world markets. However, significant worldwide unemployment, rising prices, increased pollution, civil unrest (particularly in unindustrialized or undemocratic nations), and global terrorism are negative effects of globalization.

Traditionally, the health sector has been organized at the national, state, or local level, but this is beginning to change. Groups such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the American Red Cross, and Doctors Without Borders supply aid to populations in need around the globe. Many medical schools are also increasing opportunities for medical students to complete rotations in other countries.

Urbanization refers to dense areas of population creating a pull for migration. In other words, cities are formed as individuals move into and establish residency in these new urban centers. Urbanization is not a new phenomenon; ancient populations established cities in Jerusalem, Athens, Timbuktu, and other locations. The economic opportunities offered in cities and creation of a large number of “world cities” has fueled an increase in urbanization during the last few decades. Currently, more than half of the world’s populations live in what are considered urban areas. Sociologists and other professionals have found links between urban societies and health challenges related to water sanitation, air quality, environmental hazards, violence and injuries, infectious diseases, unhealthy diets, and physical inactivity.

Cities are rarely homogenous with respect to their population makeup. Most cities have areas that are more socioeconomically well-off and others that are more impoverished. Ghettoes are defined as areas where specific racial, ethnic, or religious minorities are concentrated, usually due to social or economic inequities. In the most extreme cases, slums may be formed. A slum, as shown in Figure 11.11, is an extremely densely populated area of a city with low-quality, often informal housing and poor sanitation.