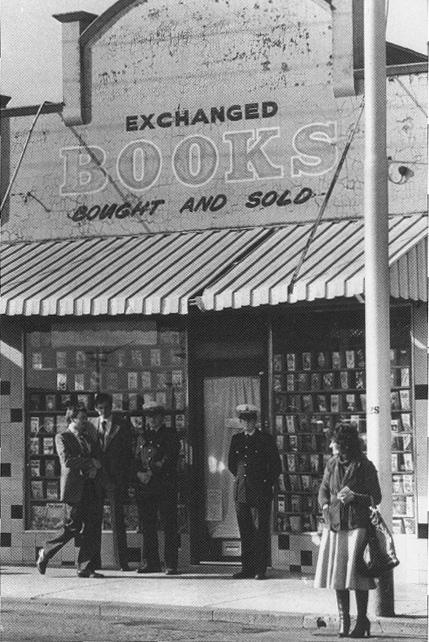

A Thornbury bookshop … scene of one of Australia’s most chilling murders. The death of Maria James is still unsolved.

ALL his adult life, David Key had been trained to control his imagination. More than a decade in army Leopard tanks and almost as long in the police air wing had taught him to concentrate on the urgent and leave reflections to others.

As he lay in the middle of a massive Bass Strait cyclone, more than 120 kilometres from shore, Key didn’t have the time to reflect on how he got there. He had to devote all his energies to getting out. Above him, literally, was his lifeline – the aging police helicopter – being battered by winds of up to 150 kph. But he knew that if he was dragged off by a monster wave, his mates above, pilot Darryl Jones, and winch operator, Barry Barclay, would detach the steel cable connecting him.

Even though they had been friends for years the helicopter crew had been trained to protect the aircraft at all costs. If Key was acting as a sea anchor and there was a risk of dragging the helicopter into the boiling sea, they would cut him loose, and he would have to fend for himself, in waves 25 metres high.

As a good swimmer and an experienced rescuer, Key was equipped to deal with even the most challenging conditions, but the weather in Bass Strait in the gathering gloom, had gone well beyond the imagination Key was not allowed to use. It was a nightmare.

The noise of the waves, the bellowing winds and sea spray hitting his face like needles at point blank range, meant that he could not hear or see the helicopter battling to stay above him. He knew he was still connected only when he felt himself being dragged along the surface of the sea – through three waves the size of small hills – by his rescue wire. It was as if he were a giant spinner being hauled along on a fishing line.

He was being dragged by the helicopter, not towards safety, but into further danger. The police air wing crew was trying to rescue John Campbell, who was washed from a yacht during the 1998 Sydney to Hobart race.

The race had begun as the traditional Boxing Day distraction for millions of Australians, but now, a day later, had turned into a maritime disaster.

THE Sydney to Hobart is like no other ocean-going yacht race in the world. In the tradition of the other great Australian races, the Melbourne Cup, and the Stawell Gift, it is a handicap event – meaning that, in theory at least, gifted amateurs can compete against hardened professionals.

Perhaps it is part of the Australian psyche to give the battler a chance. Blue-water sailing might be the richest of rich men’s sports, but the Sydney to Hobart accepts entries from weekend yachties as well as international billionaires.

Of the 115 entrants jockeying for position in Sydney Harbor on Boxing Day 1998, the yachts varied from maxis, using technology developed for the space shuttle, to the beautifully restored Winston Churchill, built in 1942, when the piston-driven Spitfire fighter plane was at the cutting edge of development. The yacht owners were as varied as the craft they sailed, from American software billionaire Larry Ellison, who arrived on his personal executive jet for the event, to Newcastle yachtsman, Tony Mowbray, who mortgaged his house to buy his boat, Solo Global Challenger, and was planning a lone voyage around the world.

The 1000 or so men and women on board the yachts were equally diverse; from professional crews, including America’s Cup veterans employed to give the maxis an edge, and international Olympic sailors looking to broaden their experience, to a group of mates from Tasmania who paid $500 each to crew on their friend’s 12-metre yacht.

They all knew what to expect. Bass Strait – a shallow, narrow piece of water dominated by two oceans and unforgiving weather from the Antarctic – was notorious, but that was the challenge. The Sydney to Hobart had not become one of the three great ocean races in the world because it was easy.

On Christmas Eve the yachties were briefed by weather expert Ken Batt, wearing a Santa’s hat. He told them they could expect to be hit by a ‘Southerly Buster’. This was typical race conditions – difficult, but not dangerous.

Yet even as the fleet cleared the harbor on spinnakers to sprint down the coast, weather experts looking at satellite pictures and computer models, issued a storm warning. What the yachtsmen didn’t know yet was that the ‘storm’ had all the signs of becoming a cyclone.

One of the great equalisers of sailing is that nature can conspire against anyone and everyone. As the fleet headed towards Bass Strait, there was a tail wind virtually sucking the yachts into the looming disaster.

Ellison’s maxi, Sayonara, recorded speeds of just under 50 kph and was on track to break the course record. Just eight metres shorter than Captain Cook’s Endeavour, the hi-tech yacht was equipped with every nautical bell and computer whistle. With satellite global positioning her crew knew their location within one metre and, below decks, laptops and faxes provided continual updates on weather and winds.

But veteran sailors know the best equipment in the world guarantees nothing if the weather turns evil. Even the great ocean liner, Queen Mary, almost capsized when swamped by a 27-metre wave, in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Newfoundland.

Gear on Sayonara, designed for any conditions in the world, began to fail. Sails ripped, brass fittings snapped and winches, made of carbon fibre and titanium, were crushed as though they were made of recycled aluminium cans. And, as the front runner, Sayonara avoided the worst of it. It would be the slower boats that would bear the brunt of the unimaginable.

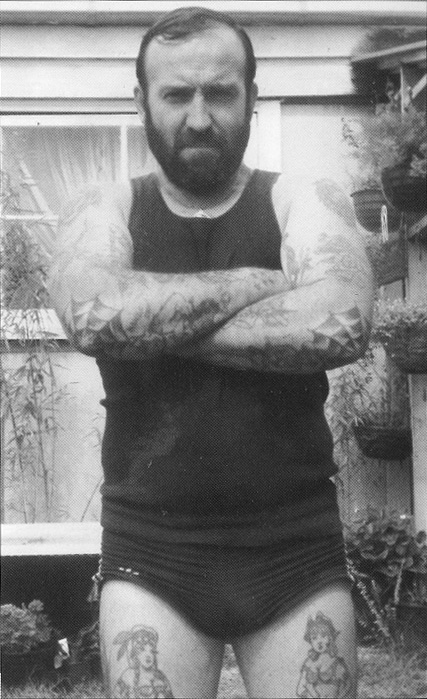

INSPECTOR Garry Schipper is a bear of a man and a legend in the Victoria Police Force.’ At 195 centimetres and 130 kilograms, he has always demanded instant attention when dealing with some of the biggest names in the Melbourne underworld.

Self-confessed killer, Mark Brandon Read, said Schipper was the toughest and strongest policeman he had met. ‘He wouldn’t hurt anyone unless, of course, they got between him and the dinner table,’ Read joked.

Schipper is also well-known and respected in the yachting world, where his power is used on the manual winches to raise and trim sails on the big yachts.

Even before the weather was to reach its most dangerous, Bass Strait was to provide a preview of what was to come. Schipper, on his 18th Sydney to Hobart race, was crewing on board Challenge Again, when hit by a giant wave. It was 2.30 am on 27 December.

He had just unclipped his safety harness to get past gear on the deck when the wave plucked him up and threw him over the rail as if he were a rubber toy.

True to Murphy’s Law, I was only unclipped for a couple of seconds when this large wave hit us,’ he was to recall, more than a year later.

Schipper was in his wet-weather gear and had taped his sea boots to his rubber pants. It was the action of an experienced sailor who wanted to stay as dry as possible, but once he was in the water his boots began to drag him under.

The rudder on the yacht was fouled, and it sailed 250 metres before it began to slowly turn. Schipper didn’t realise when he was thrown from the boat that he was still holding his waterproof torch. He was able to keep the light above his head as he was buffeted by the waves. Without the torch, his rescuers may not have been able to find him before he was swamped.

Finally, the boat pulled alongside, but he was too exhausted to clamber back on board. His younger and smaller crew mates refused to let him go in the worsening seas. Schipper believes if they had, he would never have had a second chance. Finally they managed to winch him on to the deck.

Schipper might be tough, but he’s not stupid. He is now an enthusiastic convert to wearing inflatable safety gear while sailing.

FOR the crew of Victoria Police’s Air 491, the Sunday shift just after Christmas should have been a doddle. Businesses were closed and so was half of Melbourne. But that afternoon, the air wing received a call from Australian Search and Rescue in Canberra. There had been reports of emergency beacons being activated in Bass Strait. Could they respond? The freak winds that had dragged the yachts into the disaster area did the same to the rescue helicopter as it headed to Mallacoota. The Dauphin, a French twin-engine helicopter that first flew for the police in October 1979, has a top speed of 240 kmh. When the aircrew looked down at the speed gauge, they were travelling at 420 kmh – such was the strength of the tailwind.

They refuelled and learned the situation had descended from ominous to chaotic. At least five yachts had sent out mayday calls and two were believed to be sinking. Two other yachts reported men overboard.

A young American, John Campbell, had crewed in two previous Sydney to Hobarts, but both times his yachts had been forced to retire because of gear failure.

This time he was on board the heavy-weather specialist Kingurra and he could reasonably expect to finish the race. But there was nothing reasonable about the seas in this, the 54th running of the 1000-kilometre race.

Kingurra was swamped by a giant wave and rolled. By the time the boat righted itself Campbell had been washed away and knocked out when his head hit the deck or boom.

It looked bad, but it was still salvageable, as he was connected by his safety harness to a lifeline. But, as other crew members tried to drag him back on board, he began to slip out of his harness and back into the raging sea. Luckily, the waves stripped him of his sea boots and wet-weather pants. He was alone in a cyclone dressed in a T-shirt and blue long johns.

But for the moment, the weather worked for him. When the police helicopter took off from Mallacoota with a full tank of fuel and loaded with rescue gear, it should have taken at least thirty minutes to reach the stricken Kingurra. With a howling tail wind it took just ten.

The wind was so strong, the helicopter was blown 800 metres behind the boat before it began a search pattern.

Campbell had regained consciousness and was trying to keep sight of the yacht, which was itself in danger of sinking.

The helicopter’s altitude needle showed it was about 30 metres above the sea. Then, a giant wave would rise within just three metres of the fuselage.

At one stage the pilot, Darryl Jones, looked forward and saw a wall of water about 80 metres wide. The trouble was, it was not beneath but directly in front. He slammed on power and climbed from about 30 to 48 metres, then watched as the sea rose to within a few metres of the wheels underneath.

If he had not reacted so fast, the helicopter would have been swallowed by the freak wave. But, experienced sailors say, it is not the size of the waves that make them killers – or, more clinically, ‘non negotiable’ – it is their shape and direction. In Bass Strait they would come from any direction and without pattern, often against the prevailing current.

They are sometimes called ‘green waves’ as they seem to come from the ocean floor to swamp a boat. They are so steep they are almost impossible to climb, and as they move under the yacht, there is no rear slope to surf down.

Giant yachts are left airborne. Skippers reported 20-tonne yachts dropping up to twelve metres to the base of the waves. The shock can knock the fillings out of teeth or, more alarmingly, split a hull like an over-ripe tomato.

To imagine what the injured John Campbell saw while he tried to keep afloat as dusk began to fall over the cyclone, squat in front of six-storey building and look up. Then imagine the building moving towards you at around 30 kph, and then imagine it crashing on to you again and again. Imagine you are so cold your body is shutting down the blood supply to your arms and legs, to try to protect your vital organs. Then imagine you are as frightened and lonely as you can be. That’s how John Campbell felt. But at least Campbell was there by accident. David Key, on the other hand, knew exactly what the dangers were, as he pushed off from the police helicopter to be winched into the hell below.

Key knew about danger. He had been in the army from 1973 until 1984, working as a Leopard tank commander. When he resigned from the army, he left on a Friday to join the Police Academy on the Monday, and was now in his second, long stint in the air wing.

The wind was so strong that, although they were hovering above the injured sailor, Key ended up three troughs away. He was carrying 15 kilograms of rescue gear. ‘When I hit the water I just kept going down.’

He would never have been able to swim to the injured sailor. The pilot dragged him more than 100 metres through the water to Campbell.

‘I just saw this bloodless face. I grabbed him and he was like an eel to touch, he was that cold,’ Key said.

At first he could not get the injured man into the rescue harness, and then he realised his own leg was caught in the steel cable. If the helicopter had tried to rip him from the water, he could have lost the leg.

Jones held the throttle open to a speed of 150 kmh into the head wind, just to keep the helicopter stationary above the two men. ‘Darryl did a fantastic job to keep it steady.’

Once all was clear they were finally lifted above the sea. ‘When I saw the belly of the aircraft it was the best feeling I’ve had for a long time.’

But, less than two metres from safety, the winch froze and left them hanging beneath the bucking helicopter. Finally, Barry Barclay lent out of the open door as far as his safety harness would allow, and dragged Campbell inside. ‘He just put him in a big bear hug,’ Key said. Campbell just kept mumbling ‘thank you’ while the two policeman embraced him, not with the euphoria of the moment, but to try to get some body heat back into the man who was suffering severely from hypothermia.

A Thornbury bookshop … scene of one of Australia’s most chilling murders. The death of Maria James is still unsolved.

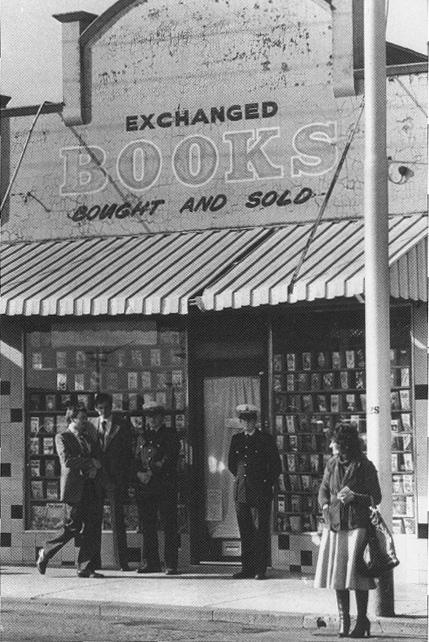

Peter Raymond Keogh … convicted killer.

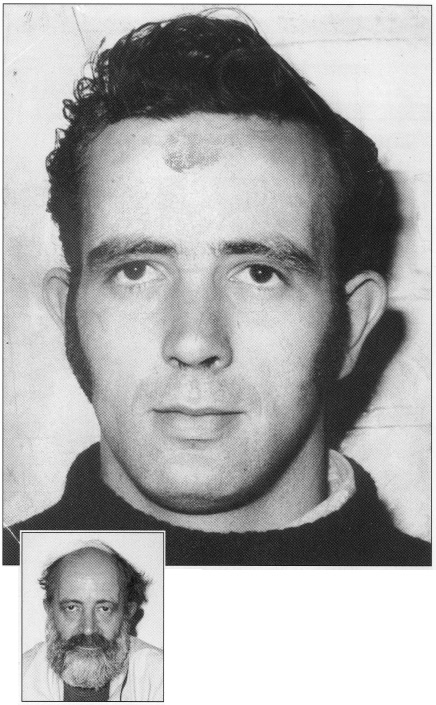

The police sketch of the man who murdered Maria Theresa James. You be the judge.

Frank MacGregor … missing, believed murdered, for 28 years.

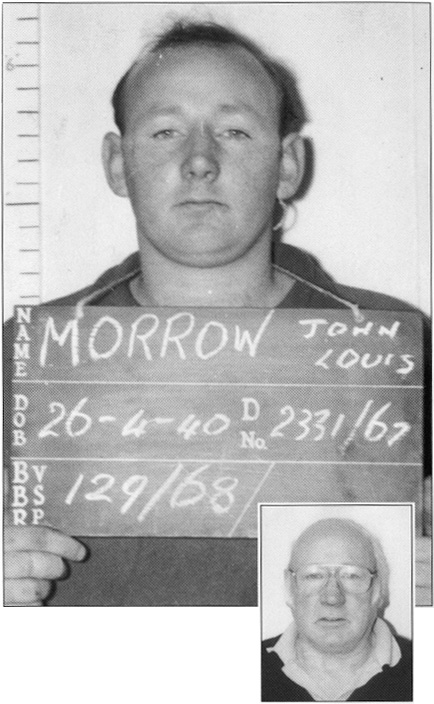

John Morrow … fled to New Zealand with MacGregor and gave the vital tip.

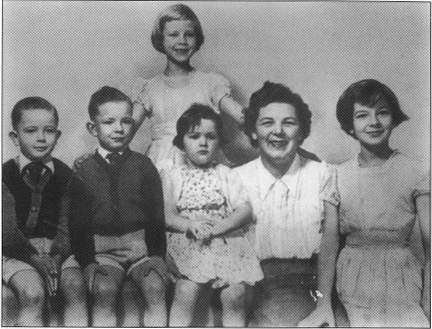

The MacGregors … Frank, Andrew, Cathy, Marjorie and Heather. Christina is at the back. Heather was later murdered.

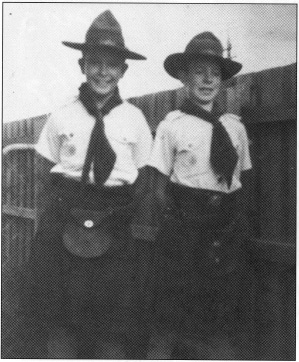

Brothers … Frank (left) and Andrew.

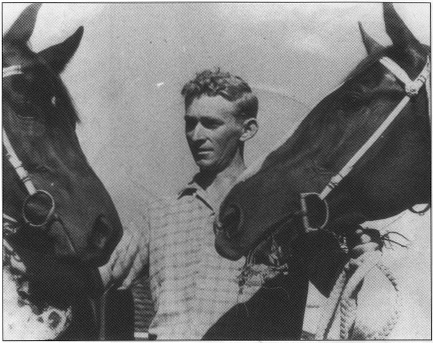

George Brown … when he worked as a strapper in Melbourne. Murdered, but on whose orders?

Phyllis Hocking … and (inset) with her mother. Murdered for her modest estate.

Phyllis and husband Jack … adopted a son. It would destroy them both.

Jack and Phyllis … looking forward to a happy retirement. It wasn’t.

A memorial marking Jack’s conservation work.

Philip’s son Brent … convicted of killing his grandmother on his father’s orders.

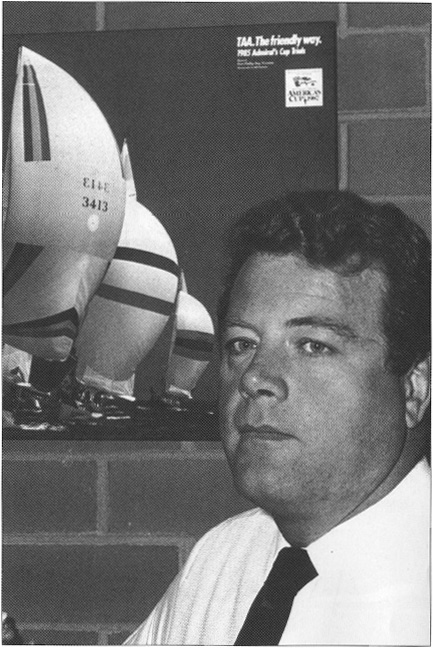

Philip Hocking … family friends described him as ‘an evil boy’.

Age did not improve him.

The first attempt to kill Phyllis Hocking … she escaped this fire in her home unit.

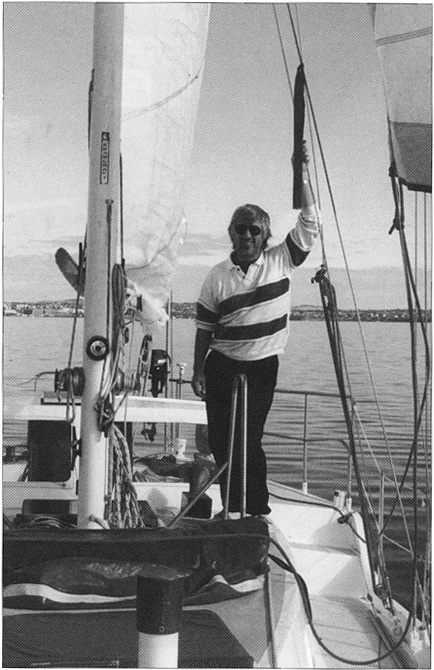

Philip Hocking … sailing to freedom while his son sits in jail.

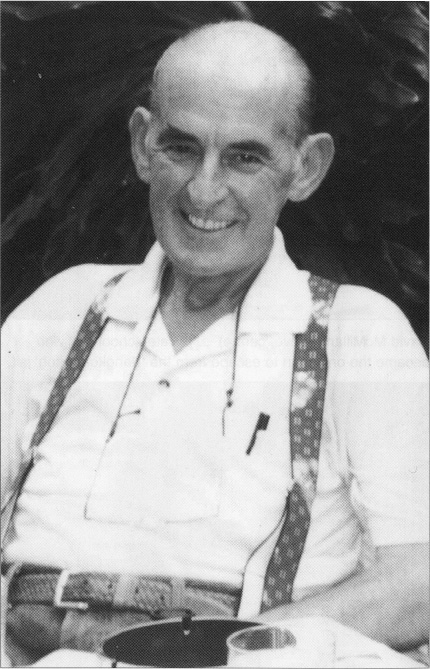

Big Garry Schipper … tossed in the sea during the killer Sydney to Hobart yacht race. He was one of the lucky ones.

David McMillan (centre) … private school boy who became the only man to escape from the ‘Bangkok Hilton’ jail.

Vale Frank Green.

It was time to head for home after the rescue. But the storm would not give up its victims so easily.

The 160 kmh wind which had brought the helicopter to the scene so quickly, was now a head wind, forcing it to travel as slowly as 40 kmh into some of the gusts.

Time was not the problem, but fuel was. The big Dauphin swallows a litre of aviation fuel every ten seconds, and while Jones wanted to throttle back to save fuel, he couldn’t because of the headwinds.

The three-man crew then heard a noise far more frightening than the roar from the waves and scream of the wind. It was the automatic fuel alarm telling them they had a minimum of five minutes left on the fuel tank to one of the engines.

The trouble was they were still 32 kilometres from Mallacoota. The arithmetic wasn’t on their side.

Barclay and Key tethered themselves to Campbell, freed the life raft and opened the rear door. They were to wait for the final order from Jones, then they would time their jump to land on the peak of the swells below.

Jones was then to fly 50 metres upwind to ditch the helicopter away from the others, so that when the spinning rotors smashed on impact, the shrapnel didn’t kill the crew.

He would then clear the helicopter and drift back to the others. That was what the textbook said, anyway.

Campbell was unaware he was about to go back where he came from, when the fuel warning to the second engine started to buzz. If they were to jump, they would have to do it within three minutes.

The American sailor would later say that one of the last books he read before the Sydney to Hobart was The Perfect Storm, the best selling account of a US hurricane, where a rescue helicopter ditched when it ran out of fuel. It was almost exactly the same situation facing the four men in the struggling police helicopter.

Key didn’t have any moments of deep thought and his life didn’t flash before him. Jones was more concerned about the repercussions of the possible crash than how he would survive it.

‘Darryl was worried about how he could do the report on how he sunk the helicopter,’ Key said.

Then, without warning, they burst out of the storm. The coast in front of them was acting as a giant windbreak and the helicopter – with virtually no weight from fuel – took off.

Jones was able to throttle back to save precious droplets of fuel. They would not try to make the local airport. At first he decided to land on the Mallacoota beach, but then he spotted the football oval 50 metres inland. A fuel check showed they had around three minutes left when they landed.

They were not finished. Next day they were back in Bass Strait and rescued four men from the Midnight Special, winching the last on board as the yacht sank.

Six men were to die in the Sydney to Hobart, but, according to Key, the professionalism, courage and calmness of the sailors caught in unimaginable conditions, meant that many more lives were saved.

• Additional material from Storm Warning, by Bryan Burrough, The Perfect Storm by Sebastian Junger, and Fatal Storm, by Rob Mundle.