THE STRATEGIC SITUATION

The Yom Kippur War, and indeed much of subsequent Middle Eastern history to date, was framed by the Six-Day War. On 5 June 1967, Israel launched one of the most audacious pre-emptive military land-grabs in history. Taking the initiative in the face of months of increasing tension with the surrounding Arab states, the IDF delivered a lightning, multi-front campaign against Egypt, Syria and Jordan. It was an action characterized by brilliance and aggressive confidence. The dash and tactical skill of the IDF meant that by the time a ceasefire was declared on 11 June, Israeli forces had taken the Sinai (right up to the Suez Canal) from Egypt, the Golan Heights from Syria, and East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip from Jordan.

The conquests of the Six-Day War provided Israel with the psychological security of a wide buffer zone between the homeland and the Arab states, a strategic depth Israel was keen to retain despite subsequent international pressure. On the other side, Arab military and political pride had taken a severe battering, and with Israel now within potentially easy reach of major Arab urban centres, including Cairo and Damascus, the governments of Gamal Nasser (Egypt) and Hafez al-Assad (Syria) looked for a strategy to reclaim their lost territory. To do so, military pressure had to be maintained on Israel.

What became known as the ‘War of Attrition’ – a rumbling series of border clashes around the Suez Canal Zone – began small, with pinprick clashes initiated by both sides, but in 1968 Nasser declared the official start of the campaign, and the fighting intensified. Egypt’s intended attrition was real – 1,424 Israeli soldiers were killed in action between 15 June 1967 and 8 August 1970, plus another 2,569 wounded – but it worked both ways, with total Arab losses from Israeli responses possibly exceeding 20,000 dead, wounded and captured.

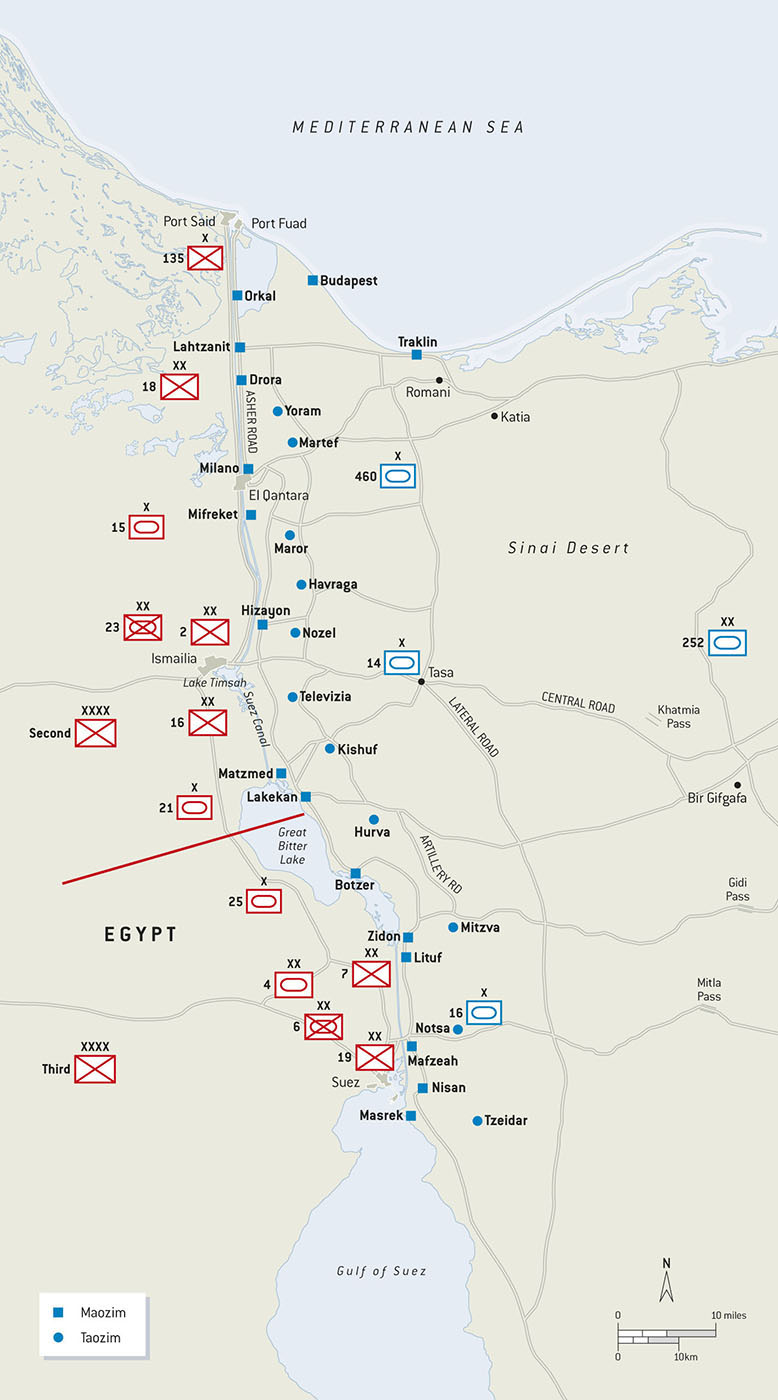

Prompted by the onset of the War of Attrition, Israel recognized the imperative to consolidate and defend the new front line in Sinai. The physical product of this understanding was what became known as the Bar-Lev Line, named after IDF Chief of Staff Haim Bar-Lev. Developed principally by Major-General Avraham ‘Bren’ Adan, this $300 million programme of defensive works would set the immediate tactical scenario for the fighting in the Sinai in 1973. The principal elements of the Bar-Lev Line consisted of 15 Maozim strongpoints that ran the entire 160km distance from the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Suez, with roughly 8–11km between each strongpoint. The Maozim were positioned to protect significant points along the Sinai front line, particularly the east–west road junctions as they crossed the north–south Artillery Road, which ran in parallel with the Suez Canal about 10km inland. The Maozim were not heavily manned – each typically had a platoon-strength unit of about 40–50 men, dropping down to about 20 men during quiet periods – but they were well sited, well-protected by frontal earthworks, trenches, barbed wire and bunkers, and well-armed with heavy machine guns and mortars. They also had prepared firing ramps for armour; when required, the tanks would mount the ramps, giving them an elevated firing position down onto the Suez Canal. Mirroring the Maozim strongpoints roughly 8km inland were some 15 larger Taozim strongholds, built into a line of rough desert hills. Each of these positions was capable of holding a company of troops, plus small numbers of tanks were kept in readiness. Larger amounts of reserve armour were held along the Artillery Road and the parallel Lateral Road further back in the desert.

The year 1970 brought two game-changers. First, in August the United States managed to broker a ceasefire between the two sides. The second, which occurred the next month, was that Gamal Nasser died and into his place stepped Anwar Sadat. The new President of Egypt was something of a challenge and enigma for the Israelis. More diplomatic, quieter, apparently even sensitive, when compared to Nasser, Sadat honoured the 1970 ceasefire (at first) and opened up negotiations with President Nixon of the United States, seeking to use international pressure to reclaim Egyptian territory lost during the Six-Day War. In this climate of detente (Nixon was also in more prolific communication with his Soviet counterpart, Leonid Brezhnev), Sadat started pulling away from the Soviet Union, in the spring of 1972 even asking the many Soviet ‘advisors’ to leave; most did so, although a key motivation was also to encourage the Soviets to provide Egypt with more advanced weaponry.

Many in the Israeli government and the Israeli AMAM, the Military Intelligence Directorate headed by Major-General Eli Zeira, felt they had the measure of Sadat as someone who was weak and who could be contained. Sadat quickly became disillusioned with the lack of progress in terms of peace initiatives, so his talk and momentum increasingly returned to a focus on making war again. In October 1972, he re-opened his interactions with the Soviets via Minister of War General Ahmad Ismail Ali, who secured the resupply of weapon systems. He also announced to his army High Command that Egyptian forces should mobilize for war, which would come soon.

The chief architect of Operation Badr – the Egyptian plan to cross the Suez Canal and seize the Bar-Lev Line – was Lieutenant-General Saad El Shazly, who became Chief of Staff of the Egyptian Armed Forces on 16 May 1971. Overcoming resistance from other commanders, El Shazly, with Sadat’s backing, proposed a limited two-front campaign (Egyptian and Syrian fronts) with manageable objectives, exercising restraint against the grandstanding ambition that had brought Arab defeat so often in the past.

In its broadest brushstrokes, the plan broke down as follows. First, a programme of deception would mask the build-up to Operation Badr from the Israelis. For example, from 1971 Sadat made warlike proclamations so frequently that they ceased to be taken seriously by the IDF, who came to treat such rhetoric as mere posturing. Second, simultaneous attacks would be launched on the Sinai and Syrian fronts, overstretching the Israeli capacity to respond. On the Sinai front, the Egyptian Second and Third armies would make a combat crossing of the Suez Canal, take the Bar-Lev Line defences, and break out beyond and form shallow but broad defensible bridgeheads against which any Israeli counter-attack would shatter. Third, from their defensive positions, the Egyptian forces could fight exactly the sort of attrition-heavy, prolonged conflict the Israelis wished to avoid, forcing an international diplomatic settlement. Sadat himself said of Badr: ‘I want us to plan [the offensive] within our capabilities, nothing more. Cross the canal and hold even ten centimetres of the Sinai. I’m exaggerating, of course, but that will help me greatly and alter completely the political situation internationally and within Arab ranks’ (quoted in El Shazly 2003: 106).

An Egyptian T-55 tank rolls through the desert on manoeuvres. The T-55 and the more modern T-62 were the principal armoured threats faced by the IDF during the Yom Kippur War. Both were effective MBTs, illustrated by the fact that the IDF put captured examples into service with the IAC. (AirSeaLand Photos/Cody Images)

On Saturday 6 October 1973, the opening day of Operation Badr in the Sinai, the IDF and Egypt brought very different capabilities to the table. Looking at the actual battle zone, Israel had about 8,000 infantry present (c.600 of them on the Bar-Lev Line), plus about 350 tanks in the 252nd Armored Division, or Ugda Albert, after its commander Major-General Avraham Albert Mandler. In reserve were the 162nd Reserve Armored Division (Ugda Bren; Major-General Avraham ‘Bren’ Adan), 143rd Reserve Armored Division (Ugda Arik; Major-General Ariel ‘Arik’ Sharon) and the 146th Reserve Armored Division (Ugda Kalman; Brigadier-General Kalman Magen). Together all these forces constituted the IDF Southern Command. Within the 143rd Reserve Armored Division were the IAC M60A1/Magach 6A tanks, contained within the 600th Reserve Armored Brigade (111 tanks) under Colonel Tuvia Raviv and the 87th Armored Reconnaissance Battalion (24 tanks) led by Lieutenant-Colonel Ben-Zion ‘Bentzi’ Carmeli. The 401st Armored Brigade also relied heavily on M60s.

On the other side of the Suez Canal, the Egyptians had amassed an extremely potent force. The Second Field Army (Major-General Mohammed Sa’ad Ma’amon; Northern Canal Zone) and Third Field Army (Major-General Mohammed Abd El Al Mona’am Wasel) together contained 90,000 infantry, although only 32,000 would actually be committed on the first day of attack, and more than 500 tanks.

The two key political players in the Yom Kippur War were the Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir (left) and the Egyptian President Anwar Sadat (right). Meir was another political casualty of the conflict, resigning in April 1974 following questions about Israel’s preparedness for war in 1973. (AirSeaLand Photos/Cody Images)

The numbers were stacked in the Arabs’ favour, but the experience of the Six-Day War had taught Sadat and his military leaders that numerical superiority did not equate to victory. The Egyptians recognized that they could not go toe-to-toe with either the Israeli Air Force (IAF) or the IAC and come out the winner. What was needed was a different approach to equalize the odds. For the air campaign, Nasser then Sadat had pressured the Soviets to supply a sophisticated umbrella of S-75 Dvina (SA-2 ‘Guideline’) and S-125 Neva/Pechora (SA-3 ‘Goa’) SAM systems and MiG-21 ‘Fishbed’ fighter squadrons, plus some 2,500 AA gun systems. Using the same logic at ground level, the Egyptians bolstered each of their infantry divisions with at least 48 Sagger missiles, plus 314 RPG-7s to cover the 0–500m ‘dead ground’ that the Sagger could not handle. All of the anti-tank missiles within each division were collected into an ATGW battalion, giving the infantry division a powerful tank-killing tool.

Evidently with a lot on his mind, IDF Chief of Staff General David Elazar looks down over the Sinai battlefield from a helicopter on 19 October 1973. Following the conflict, Elazar received an unfair share of the blame for initial failures in the campaign, and he resigned shortly after the war. (AirSeaLand Photos/Cody Images)

The Yom Kippur War brought together two different approaches to armoured warfare. One, the Israeli, focused on the supremacy of the tank itself as a vehicle for deciding the battle. The other, Arab approach (Saggers were also heavily deployed by the Syrians on the Golan Heights) sought to reduce the tank’s authority by subduing it in a wide zone of lethality, created by the ATGWs and the RPG-7s. It was an unprecedented clash.

This map of the dispositions of the Egyptian and Israeli forces on the eve of battle on 6 October 1973 strikingly conveys the scale of the threat gathered against the IDF. Two Egyptian field armies – true combined-arms forces of infantry, armour and artillery – were amassed on the western side of the Suez Canal, ready to attack across it and establish a shallow but well-defended strip of territory on the eastern side. The Israelis’ main line of defence in the Sinai comprised the 15 Maozim strongpoints and 15 Taozim strongholds that together constituted the Bar-Lev Line, but these were not heavily manned and the spaces between the positions provided avenues for the Egyptians to bypass and surround the strongholds. IDF armour of the 252nd Armored Division was available in the Sinai, but largely held back in reserve positions further east; it would take time for them to respond fully to an emerging crisis in the Suez Canal Zone.