I am not interested in money, and my purpose is entirely scientific. I shall enter [a forest] naked and take with me absolutely nothing. I shall see absolutely no one. I shall keep a birch-bark record with charcoal of my progress and place it each week under a stump where a trapper will get it and send it to the Sunday Post.

—Joseph Knowles, 1913

[T]he simple life ain’t so simple.

—Van Halen, “Runnin’ with the Devil,” 1978

My naked survival campout was going very well until I sat on a yellow jacket nest. It happened around half past noon, judging from the position of the sun.

At the time of the incident, I had been hanging around for about a half hour in a remote corner of the Santa Cruz Mountains on California’s Central Coast. I was on a green and bushy hill, a steep forty-five-minute bushwhack from the nearest trail. My car was five miles away, on the side of a country road. In this untrammeled section of the Soquel Demonstration State Forest, I saw no fence posts or signs, no barbed wire, or any other indication that a human had been there in a long while.

I had no tent on me, no survival knife, flashlight, sleeping bag, underpants, water bottle, toilet paper, bug spray, or first-aid kit, and no way of calling out for help. I had brought my baby-blue Xopenex inhaler because I can’t breathe without it. I’d also brought my prescription glasses and half a whole wheat peanut butter and honey sandwich, which slipped out of my hand and landed in a pile of deer scat the moment I arrived on the hill. Never mind. At dinnertime, I would forage for a tangy green plant called redwood sorrel, and see if I could find any sticky monkey flowers for dessert.

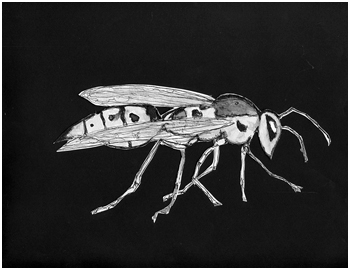

The yellow jacket can sting its victim multiple times.

Still, the sandwich incident reminded me to be more careful. Even small mistakes would have consequences in a 2,681-acre state-administered forest reserve that would be deserted when the sun went down. Camping wasn’t even allowed up there. I had had to get a special-use permit and sign a document promising that my family “under no circumstances” would sue California if something awful happened.

In those fleeting moments before the wasps arrived, I loosened up a bit, while maintaining my hypersensitivity to the woods around me. It felt so freeing to be naked in a place like this. I couldn’t remember the last time I was that present inside my body. I spent a good long while just staring at my left arm, admiring it. I lifted it up and down, counting the freckles and the little blond hairs and examining the crease where the arm met my shoulder. I wriggled my toes in the mud, which was rich and crumbly and smelled like mold. Then I spent a while examining my gastrocnemius muscles. Tan oaks and second-growth redwoods shaded me from the sun as I walked barefoot through a luxuriant canopy of wild ginger and five-fingered ferns. I put my hands on my hips and breathed in. A glory beam lit up a clearing in the middle of the grove, the tree roots all knotted together, forming a circle. The wind whispered against my buttocks.

The only thing that bothered me just a little bit, and prevented me from relaxing too much, was the slight chance of encountering a cougar.

They lived there. I don’t mean to suggest that they lived, exclusively, inside the Soquel Demonstration State Forest. Cougars roam around; they have places to go. Sometimes they even show up lost and confused in downtown Santa Cruz. But the forest is part of their habitat. I once attended a lecture by a mountain lion expert named Chris Wilmers, who said the chance of getting eaten by a mountain lion was less than the chance of impaling yourself accidentally with a toothbrush, the sort of thing that happens only in the Final Destination horror movie franchise. Still, you can’t be too careful, so I made a point of scanning the treetops every once in a while for sunbathing apex predators with eyes the size of golf balls and yellowy slits for pupils. It did not occur to me that a much more immediate danger was hiding in the earth beneath my feet.

Feeling thirsty, I crept up the ridge to the source of Badger Spring, a few hundred feet away from the place where I would be sleeping for the night. There, I crouched, cupped my hands, and filled my belly with the most delicious spring water. I rubbed a little bit of that water in my hair and on my chin and dabbed some on the sides of my neck like eau de cologne. For all I knew, I was the first person to camp here ever. This was the first time a piece of forest ever really belonged to me. I let the forest soothe me. There was no separation between me and nature.

That’s when I first heard the buzzing sound, like an electric current moving through a power line. The noises seemed to be coming up from below the ground. “Oh, no,” I said out loud, because only one creature on earth made that particular Bzzzzzzit.

I stood up and brushed the dust and dirt off me. Too late. A dozen yellow jackets circled me, bobbing up and down in the air.

I knew from experience that yellow jackets are monstrous in a way that transcends mere cruelty. They are incapable even of indifference. It’s very possible that they have no thoughts, just a bunch of white static. You cannot reason with bugs. I’d been stung before, badly, in Point Reyes, California. I went into mild shock, and my arms turned the color of Vienna sausages, the kind that come in jars. My wife had to sit by my side for hours and put a cold compress on my head because I was burning up.

No, I could not get stung again, even once, not while I was naked. And what if the yellow jackets stung me down there? What then?

I wanted to run, but that was not an option, because the ground was steep and uneven, full of little snags, rocks, roots, and gullies, and I had no shoes on.

The sound was loud now. Wasps everywhere. Keep calm. Don’t panic. Just get to your tent and seal yourself in.

But there was no tent, no nothing in my camping spot, just a pile of leaves and a rotting log.

My chances of escape were slim, but I had to try. What choice did I have? I couldn’t run, exactly, without scraping and bashing my feet and toes. The only option was to take a series of small but powerful uphill leaps as the yellow jackets closed in on me. With my hands cupped in front of the most vulnerable and sensitive region of my body, and my backside exposed to the fates, I bunny-hopped through the forest, screaming.

In those moments before the inevitable happened, my mind filled with nothing but fear. As I fled from the wasps, my decision to be out there in the first place suddenly seemed impulsive and absurd, the worst idea I’d ever had.

The fact is, I had never prepared so hard for any camping trip in my life. I’d hashed out every aspect for weeks in advance. I even chose the departure date, August 3, 2013, for its historic value. In the summer of 1913, one hundred years before I started my own nude survival experiment, the good people of Boston, Massachusetts, opened up their newspaper and saw a story that must have made them choke on their cream toast with prairie chicken.

Joe Knowles, a middle-aged Boston-based painter, wildlife illustrator, onetime hunting guide, and former navy man, declared that he would enter the Dead River wilderness of Maine, 250 miles north of the city, without a stitch of clothing on his doughy, five-foot-nine-inch corpus. Never mind that he was a chain-smoker and heavy drinker whose appearance did not inspire confidence. He had a nose like a crookneck squash and weighed 204 pounds, but he didn’t seem to care. He would prove to America that he was a winner.

Even in the era of woodcraft and survivalism, his plan was audacious. For two months in the woods, he would dwell among the coon cats, meadow voles, and woodchucks, enjoying no contact with humans. Knowles would have no premade tools, books, implements, or weapons. To mark the days, the Nature Man, as he came to be known, would cut notches in a tree with a stone axe made of foraged materials. The woods would be his Walmart. If he got hungry, he’d kill an ungulate. In a year of assembly lines, slums, child labor, tenements, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, difficult modernist fiction, the institution of the Federal Reserve Act, and America’s first income tax, Joseph Knowles was going to live like it was fifty thousand years BC. By the time of his campout, many other Americans, most notably Theodore Roosevelt, had preached the importance of the “strenuous life” and living up to the grit and the resourcefulness of the pioneers. Knowles was trying to be the ultimate exemplar of that raw and adventurous lifestyle. And for a while, at least, people as far away as Chicago knew his name. His breathtaking naked camping stories got more attention than the 1913 World Series.

By being out there in the woods, I wanted to pay tribute to this man, and get a better sense of the excitement and misgivings he experienced firsthand. Most of all, I wanted to feel the “full freedom of life” that he describes so vividly in his writings about the camp. What would it be like, even for twenty-four hours, to do as Knowles did, taking up Thoreau’s challenge of “Simplicity! Simplicity!” and pushing it to the logical extreme? I thought this campout would disprove all the ideas I’d accumulated about myself: that I’d lost my boldness, that I wasn’t half the man I was when I walked the Pacific Crest Trail. It would also be a way to slough off all the useless pieces of camping equipment I’d accumulated over the years. His message resonated with me: an ordinary-looking middle-aged man could reinvent himself in the woods.

Knowles’s underdog credentials were secure. He grew up poor and, in the grand tradition of many famous American campers, had the requisite lousy relationship with his dad, who bullied him. As a child, his peers taunted young Joe for snacking on sowbelly and using a lard pail as his lunch box. Now he had a chance to prove those schoolyard bullies wrong.

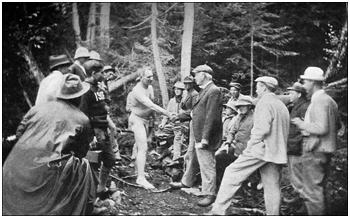

At 10:40 a.m. on August 4, 1913, Knowles took off his brown suit and stripped to a white cotton jockstrap, which he wore for propriety’s sake. Now he looked pudgy and pale as he stood before the group of reporters and wilderness guides. He struck a few poses and flexed his muscles in the drizzle. “My body was already glistening with the rain, but it didn’t bother me any,” he remembered later on.

A doctor examined him. One well-wisher asked if he would like one last cigarette. Knowles accepted it, took a few puffs, and tossed it on the ground. This, in itself, was quite a cocky gesture; it must have been hard to give up a serious smoking habit just before a stressful and possibly life-threatening journey. Perhaps this final puff was a message to the crowd: I am capable of anything. Willpower is only the beginning of what I can do.

Joseph Knowles strips down to his jockstrap in front of a group of well-wishers and curiosity seekers. Image from Alone in the Wilderness.

People in the crowd, especially the survivalist types, must have wondered why Knowles was so sure of himself. In the days before his departure, friends “literally begged me to abandon the idea,” he said. What was Knowles’s secret? Why was he so self-assured? People vanished in the Maine woods from time to time. Besides, without “bug dope,” a sticky pre-DEET insect repellent consisting of pennyroyal boiled with pine tar and castor oil, Knowles would be defenseless against blackflies, which bit so hard they left welts and blood puddles. No problem; before the campout, Knowles, a native of rural Maine, planned to reach high elevations where mosquitos could not be found. He had been experimenting with natural repellents, including foraged mint leaves smeared all over his body.

In the final moments before his adventure, Knowles smiled at the onlookers. “See you later, boys!” he said, and walked away in his flimsy codpiece.

A local camp operator and a hunting guide tracked Knowles for a while, but they turned back after a few miles. Knowles, seeing that he’d lost his unwanted escorts, discarded the jock strap and headed off into the unknown.

Two months before my own naked campout, I took the first necessary step toward learning how to survive like Joseph Knowles: I went out and hired a wilderness consultant.

If I lived in any other city in America, finding someone to advise me on the art of nude camping might have been a challenge. But my home is in Santa Cruz, California, where you can find someone to teach you just about anything. If you’re interested in soul retrieval and acupuncture for cats, we’ve got the expert for you. We once had a self-proclaimed “Breatharian” who claimed he could show people how to eat and gain sustenance from food odors (while leaving the food intact). He was gaining some traction until a story started circulating about him devouring a pot pie from 7-Eleven, followed by Twinkies and a Big Gulp.

One wonders how such wildly impractical people could get by even in the short term in a town where the median home price is $755,100. Here’s my theory: Santa Cruz forces iconoclasts and creative-minded people to become extreme survivalists in one way or another. The few who can stay here in the long term without selling out or going broke must have a wiliness, resourcefulness, and endurance that would rival those of any naked camper on reality TV.

It did not take long for my search to lead me to Robin Bliss-Wagner, perhaps the wildest man in Santa Cruz. I met him during one of the all-day intensive wilderness skills classes that he teaches at the University of California, Santa Cruz campus. Robin is a dashing young man with long hair tied up in a loose ponytail. His aquiline nose reminded me of a goshawk’s beak. Something about his eyes brought to mind an owl or a kestrel. It must have been his steady watchfulness, and the sense that he was casing out his surroundings at all times without comment, looking for any movements, disruptions, changes. I had the sense that Robin was taking note of everything and everyone, adding it to a mental Filofax that never ran out of pages.

Unlike the blustering Joe Knowles, Robin is soft-spoken, gentle, and humble, but he’s a keen-eyed stalker of prey animals. He told me about the times he’d taken squirrels with a homemade bow and arrow. “They’re just as good as chicken,” he insisted.

Most of his interactions with animals are peaceful. He loves to observe them. Robin talked about holding himself so still in the Sierra Nevada foothills, willing himself to vanish, that black bears sauntered past him without giving him so much as a sniff. I asked if he’d camped out naked in the forest. “Several times,” he told me. He once slept in the buff beneath a bunch of acacia pods, and though the air above him was frosty, he was steaming hot beneath his blanket of vegetation. He hones his skills through constant learning, and always seeks out people who know more than he does. Alongside his tracking mentor, Jon Young, a protégé of the survivalist, best-selling author, and animal tracker Tom Brown Jr., Robin traveled to Africa to learn wilderness skills from Kalahari Bushmen, who astounded him with their birdcall analysis. He remembered one instance in which a Bushman, hearing a bird’s distress trills, said that he knew which animal was menacing the bird (a mongoose) and the direction of the predator’s approach (from the southeast).

When I told him about my plans to do a survival campout in honor of a once-famous naked woodsman named Joe Knowles, Robin laughed. I detected no malice in his laughter, only enthusiasm and amused interest. He cautioned that his seven-hour session could teach me only so much about camping naked.

He and his students picked some green and spiny leaves of yarrow, a powerful coagulant; crush it in your mouth and secure it to your wound with a loop of buckskin and the bleeding will subside, Robin told me. He showed me a plant called mugwort, a delicate and fuzzy weed that makes excellent tinder and serves as a “coal enhancer” for friction fires. As we slipped in and out of forests overlooking the eco-brutalist buildings of UC Santa Cruz, he taught me how to take a carved wooden spindle, secure it to a piece of cord, tie the cord to both ends of a curving stick as long as his arm, and then work the stick back and forth in a blur of motion, making the spindle turn so fast it burned a hole in a piece of soft wood, creating a smoldering, peanut-size coal that Robin enrobed in mugwort and duff.

He blew his bundle gently, and foof!—there was fire. Speechless and amazed, I decided right then to hire him as my naked campout trainer. Robin became my frequent companion in the forests of Santa Cruz in the weeks leading up to the big event I called Knowles Day, the one hundredth anniversary of Knowles’s campout. Robin taught me more than survival. Together we studied a tight piece of rabbit-fur-tufted bobcat shit. We chewed Douglas fir needles, chock-full of vitamin C. He showed me how to quiet my mind in troubled times by using a process called Owl Eyes. All you do is focus on the middle distance and still your brain so you notice the slightest swaying of a tree bough, a tremble in the underbrush, and the flicker of a bird’s wing. In teaching me this skill, Robin enhanced my ability to look; while taking a hike on my own in between my training sessions, I saw, for the first time, an endangered Ohlone tiger beetle, its iridescent green shell rattling through the high grass at Moore Creek Preserve, in Santa Cruz. On one of our long walks in the woods together, I told Robin how much I despised certain animals and plants, and he asked which insect I hated most of all.

“Yellow jackets!” I said.

He gently admonished me for loathing wasps. Most of the time when they attack you, they are just protecting their young and following pure instinct, he said. Besides, they are janitors of the wild. He asked if I’d ever seen yellow jackets swarm around a carcass. If I looked closely enough, I’d see that each yellow jacket was carrying a small piece of meat ripped from the dead body. Somehow the thought of this brought little comfort.

“But how do I stop yellow jackets from stinging me?” I asked him.

He said that if I held my ear close to the ground, I could hear them buzzing. It was always good to scan the earth this way before digging around looking for vegetation to build a shelter.

“But what if they come after me?”

Robin smiled at my question. “Run!” he said. “Run like hell.”

When Robin teaches intensive nature skills courses to adults and youth, he is responding to a “collective hunger” he shares with Americans who feel they have been separated from the land for far too long. While he was telling me about this primal need to be in natural areas, it occurred to me that it was this same longing that had led to Joe Knowles’s massive fame a century before. That was a time when progress-addled people took solace in stories that highlighted the primitive in fantastical ways, including the Tarzan tales of Edgar Rice Burroughs. The nation was learning that technology and comfort had their limitations. A year before Knowles did his naked campout, the state-of-the-art and luxurious Titanic sank to the bottom of the ocean off the coast of Newfoundland, killing 1,517 people.

Knowles may have been fleeing the excesses of the twentieth century, but he made sure in advance that thousands of people would follow his every move in the woods. Before the campout, Knowles signed a deal with the Boston Post, a workingman’s newspaper and the archrival of William Randolph Hearst’s flashier Sunday American. For added authenticity, Knowles would write each report from the forest on a birch bark roll and include drawings of animals. Using burned bits of charcoal, he would scratch out and illustrate dispatches from the deep woods.

He was the whole picture, skilled but human and relatable, and because of his extreme subject matter, he had a built-in massive audience. In that sense, Knowles was America’s first outdoor survival “reality star,” predating by nearly a century the contemporary survivalist programming on television, including Naked and Afraid, a series featuring the exploits of naked campers trapped in jungles. Another recent example is a 2014 series called Fat Guys in the Woods, in which a group of marshmallowy and clueless men are led by soft-spoken, earnest-eyed survivalist Creek Stewart into a forest, where he teaches them to make friction fires, forage for wild grapes, and catch prey.

Those campouts are glorified publicity stunts, and so was Knowles’s. But Walden, in some sense, was also a publicity stunt, an extreme gesture designed to inspire, confound, and provoke American readers. Knowles’s admirers thought of him as a genuine woodsman, unlike those egghead transcendentalists who knew next to nothing about hard-core survival. Ralph Waldo Emerson and his buddies had to take along a wilderness guide for each member of their camping party in the Adirondacks. Knowles marketed himself as the real deal, a master of camping in its rawest form. One minister, interviewed by the Post, predicted that Knowles would “share the fame of [Henry] David Thoreau.”

I longed for my own chance at naked camping glory, but was starting to wonder if it was ever going to happen. Robin was showing me how to do my experiment successfully. The trouble was, I couldn’t figure out where the adventure should take place.

Originally I planned to do the trip in Maine, to honor Knowles, but decided it made more sense to camp nude near my hometown. Knowles, for all his bravery, made sure to camp in a forest he knew well. Why should I place myself in a completely unfamiliar landscape? As far as I could figure out, though, the only way I could do this locally would involve trespassing, which I did not want to do. I could just imagine the headlines in the Santa Cruz Sentinel: “Asthmatic Nudist Flashes Felton Grandmother; Deputies Summoned.” The best approach would be camping on private property, where no one would hassle me, and I would break no state laws, as far as I knew. But it was hard to find a parcel that met my extensive needs, and none of my landed-gentry acquaintances would return my phone calls.

I decided to try my luck with the good people over at California State Parks, but they had serious reservations about letting me camp on public lands. One stumbling block was my planned display of nakedness, a misdemeanor in California, which had rules against anyone “willfully” and “lewdly … expos[ing] his person, or the private parts thereof.” To make the trip more palatable, I agreed to put on a skimpy loincloth to avoid shocking anyone I might meet in the woods. I also discarded my original halfhearted plan to hunt squirrels with a primitive spear called an atlatl. Instead, I planned to take along a super-realistic squirrel toy I’d ordered on Amazon so I could practice “hunting” it instead. There are no state laws against killing something that never lived.

Yet the rangers would not be mollified, even when I decided not to build friction fires, which I was bad at doing anyway. One of them, who worked at the Wilder Ranch State Park in Santa Cruz, told me my plan to harvest plants and build a “foliate debris shelter” would violate state park laws by damaging wood, “and then when you write about it, you will encourage someone to do the same.” I tried to assure him that I would attempt to follow “Leave No Trace” practices as closely as possible. I would merely displace some fallen deadwood and then put it back where it was. “I will only eat small handfuls of delicious wildflowers,” I told him. “And I will attempt to harvest them in a sustainable manner.”

The ranger would not change his mind.

I was just about to hang up the phone and forget this crazy campout altogether when the ranger said, “I just thought of something. Have you tried the Soquel Demonstration State Forest?”

The ranger’s suggestion surprised me. I’d visited the place for a few hours with my wife; we took a hike there. It was dry, dusty, and hot, ringing with chain saws and smelling like sawdust. The place was also full of mountain bikers. Then I remembered that Knowles’s experiment took place in a nonpristine forest chockablock with hunters’ camps. The ranger told me that the rules regarding overnight campouts might be a little different at the “Demo Forest,” because loggers “sustainably harvest” lumber there; in other words, the place doesn’t pretend to be a howling wilderness.

Still, I was jumpy when I called the forest management office. What if they rejected me, too? They put me on hold forever, and while I was waiting, the voice mail system played a spooky old song called “A Forest,” by the Cure, about a man who gets lost in the woods running after a girl who turns out to be an apparition: “The girl was never there.” The spirit, it seems, is luring him to his doom. By the time the forest manager Angela Bernheisel got on the line, I was so unnerved by the song that I almost lost my chain of thought. Bernheisel listened to my elevator pitch without comment. Then she took me off guard with her sudden and enthusiastic yes. I felt elated on the one hand, and also had a sobering realization: “Good God, I’m actually going to have to do this thing.”

She said she would make a special exemption to their no-camping rule because my campout sounded “educational.” She cautioned me not to camp in a riparian corridor, where mountain lions love to hunt and where the temperature can drop to forty degrees Fahrenheit, even in summer—precisely the kind of place I needed to camp if I wanted access to clean water.

When Knowles Day arrived, in early August, I was feeling proud, sure of myself, and well prepared. Cougars, schmougars, I thought. Nothing was going to hurt me out there.

By then, I’d had one last intensive practice session with Robin. Just to make sure I was ready, the two of us had visited the Soquel Demonstration State Forest a week before the day I’d scheduled for my naked campout. He’d bushwhacked up the hill with me, led me to a reasonable spot for camping, and even helped me build part of the shelter I would occupy that night, though he left it up to me to complete the job. While I nibbled on a chicken burrito, Robin led me to good water just up the hill. He’d homed in on the source of the creek to minimize my chances of drinking runoff water infected with animal wastes.

I was as well prepared as I could ever be.

But my wife, Amy, did not like my idea one smidgen.

We’d been together for thirteen years by then. She knows I can be impulsive and self-sabotaging. Sometimes she thinks of herself as my unpaid life manager and, other times, as a topiary artist. I am her unruly tree; she is always making artful snips. In other words, Amy tries to motivate me when I’m apathetic, but she also tries to prune me back, especially when I’m obsessing about something she thinks will cause me harm. On the morning of my departure, she tried once more to talk me out of going, even while I was hauling out my loincloth and stuffing a few provisions into a cotton sheet I’d bought at a yard sale and cut in half.

Amy sighed. “I’ve been telling my friends about what you’re doing, and they think it’s weird, and not in a good way,” she said as I was getting ready to leave. She pressed a peanut butter and honey sandwich in my hand and made me promise I’d eat it. “You were never supposed to push it this far,” she said. “You told me you were going to go out and camp naked for one or two hours at the maximum. You weren’t going to spend a whole day and night in a forest with no clothes on. I think your parents need to know about this right now.”

“Please don’t tell my parents,” I said. “They’re Jewish. They won’t understand.”

Only my daughter, four years old at the time, did not seem the least bit worried. She handed me a diagram she’d made of my shelter. In her mind, it had plenty of blankets, even a functioning toilet. If anything, she seemed thrilled for me. “Stay warm in your shelter, Daddy. Bring pillows. Don’t get splinters.”

I understood my wife’s fear, but I had no choice. How was one hour going to give me even the dimmest sense of what Knowles experienced?

* * *

I arrived at the Soquel Demonstration State Forest at 10:00 a.m. in my scratched-up Toyota Corolla. The rural road and dark woods behind it seemed so remote to me then, though this place was only forty minutes from our dingy rental house in Santa Cruz and ten miles from Highway 17, which passes through the green mountains and links Santa Cruz with Silicon Valley. Up to thirty thousand commuters drive on it every day. Many of them toil in the tech industry. How strange to take such a highway to my own personal Stone Age.

Joe Knowles believed he was leading America back to Neolithic times. He would prove by example that man could achieve “vigor and energy and pleasure for the life led by the original cave men,” wrote the Chicago Tribune in a 1913 news story that was a barely disguised fan letter to Knowles. Now I wanted to follow Knowles into the forest. I parked my car near the entrance to the Soquel Demonstration State Forest. When I got out of the Corolla, I was wearing only tennis shoes and a loincloth, which I’d made from a flap of scratchy deer hide, a long and tapering strand of deer gut, and a sustainably harvested deer horn for a clasp. I’d bought these items for a total of $13.67 at a Santa Cruz leather store that caters to survivalists and bondage enthusiasts.

After stepping from the car, I noticed four squadrons of mountain bikers preparing for their morning ride; the Demo Forest is popular among fat-tire fanatics. Some of the cyclists were looking at me. On the dusty hood of my car, I unrolled half a cotton sheet, dropped a few survival items in the center of it, rolled it up tight, and draped it across my shoulders. I was just making sure the car doors were locked when a cyclist rode up to me with a look of grave concern.

“What do you think you’re doing?” he said, looking me up and down.

Caught off guard, I tried to explain the historic nature of my naked camping project, its origins and specific precedents, harkening to survivalists in the early years of the twentieth century, when Americans revolted against modernity by embracing primitivism.

“That’s fine,” he said, “but you’re crazy to leave your car on this road. We’ve got crackheads. They’ll bust your windows. They’ll cut your tires.”

“You’ve got crackheads and cougars up here?”

“At least put your things in the trunk, where the crackheads won’t see it. They’ll steal everything. They’ll sell it for drugs.”

“All I’ve got is junk.”

“Even junk!”

I did as the man told me to do, placing my daughter’s eyeless, legless dolls, stick figure drawings, empty bottles of Tugaboos baby wash, and half-melted crayons in the trunk, alongside my balled-up socks and coffee-splattered back issues of Poets and Writers. Still, I felt discombobulated as I made my way toward my camping area. I couldn’t stop thinking about the crackheads who haunted this area, although I just had to wonder if the cyclist meant “crankheads,” which is a more sylvan demographic than crackheads. It took a little while, but I was able to center myself by taking deep breaths until I pushed those druggy car burglars out of my mind. Nothing I could do about it anyway. This was the chance of a lifetime. I couldn’t blow it by worrying too much about a few meth zombies. Car windows could be replaced, but this moment might never come again.

I jogged down the unpaved Hihn’s Mill Road, a glorified dirt track, the sun breaking through redwoods at intervals. A bike-squashed snake lay in the dust like a rubber toy. Dozens of helmeted cyclists passed me by. I can’t blame them for staring so contemptuously at a bald guy running down the road in a getup that looked exactly like the one Raquel Welch wore in One Million Years B.C., minus the bikini top and sexual frisson. The loincloth was just my way of staying true to the primitive spirit of my survival campout without flouting California’s public nudity laws.

After a while of jogging, I reached the bottom of the slope and saw the Badger Spring waterfall, about five miles downhill from the place where I’d parked the car. With every step, I imagined Robin was with me, giving advice. On the way, I remembered what he told me during our visit to this forest. When I arrived at my designated point of departure, I would rest for a moment, then leave the possessions I’d rolled inside the cotton sheet, including my flashlight, fleece jacket, bottled water, knife, and the lifelike stuffed squirrel toy, in the hollow of a redwood tree. Robin simply called this designated hiding place “X marks the spot,” but I chose to call it the Tree of Cowardice, or the Chickenshit Tree; it would be waiting for me if I decided to “chicken out” of my naked camping adventure.

Yet this clever plan had a catch. If I decided the naked campout was too much for me, as long as there was light, I could make my way down from the steep and trackless woods, retrieve the flashlight and other gear, and hike right out. Once the sun went down, however, I would have no way of descending that heavily forested and treacherous hillside in pitch-black darkness and retrieving my gear. At that point, I would be stuck on the hilltop for the night.

At the bottom of the hill, I left the dirt road and found a suitable redwood to store my provisions. There I left my survival gear, including all my warm clothes. I also left the plushy squirrel toy I’d bought online from Amazon. Then I started hiking barefoot up the hill, but the ground was so sharp and poky that I decided to go back to the Chickenshit Tree and retrieve my sneakers. I was just reaching into it when a plague of unwanted rational thoughts began to assail me.

What are you doing? I said to myself. You’re going to freeze your ass off in your shelter! Don’t just take your sneakers. Take all the rest of the gear with you! This is insane.

Struggling with indecisiveness, I reached into the tree, scooped up all my clothes and equipment, and began hiking up into the forest, cradling my belongings in my arms. That’s when another scolding voice began to shout in my head. Coward. Fraudster. You are violating the rules you set for your own campout. Put it all back! Reluctantly I hiked back to the Chickenshit Tree. Though I could not bear to take off the sneakers, I left the windbreaker, the knife, the map, the compass, the flashlight, the leggings, and even my fuzzy insulating jacket.

I took the squirrel.

For the next forty-five minutes, wearing only shoes and a loincloth, and still clutching the cotton sheet in my arms, I hiked my way up a slippery slope covered with tan oaks, a misleadingly named evergreen hardwood that is actually part of the beech family. Their trunks were gray and bumpy, like elephant skin. Their leaves were blue and waxy, with prickly edges. An exotic water mold, Phytophthora ramorum, had made them dry and spongy and ready to topple over. Sometimes I would reach out for one of their branches and try to pull myself up; the rotten wood broke off in my hand.

I tightened the clasp and readjusted the loincloth, which was slipping down my hips. Holding my head close to the ground, I used the spring’s faint traces and the orientation of the slope to make my way toward the place Robin had selected as my camp. At times I felt lost; the forest seemed to swirl around me, giving me vertigo. A dark-eyed junco offered some much-needed encouragement from the bushes. “Neat, neat, neat!” he cried. “Thank you!” I cried back.

Rather than allowing myself to dwell on my misgivings, I focused on the insurgent cheekiness of my campout. I’d gone to extremes to keep my experiment pure. I’d brought no water filter, no water purification tablets of any kind. Of course, giardia was a real concern; I’d gotten a bad bout of it on the Pacific Crest Trail twenty years before, lost twenty-five pounds, and looked in some of my trail photos like the nut-brown, shriveled-up Mummies of Guanajuato. That’s why I now scrambled as close to the source of Badger Spring as possible: the last thing I wanted was raw drinking water contaminated with creature turds.

Halfway up the hill, I entered a thick redwood grove. The time had arrived for me to ditch the loincloth and shoes. No more delays. No more excuses.

In a sunlit clearing between a fairy circle of slender redwoods, I reached down and undid the deer-horn clasp. With a Gypsy Rose Lee shimmy shake and a teasing twirl, I let the flimsy garment slide down my midsection, slip down my thighs, and puddle around my ankles. Then I removed my tennis shoes and buried them under a pile of rocks along with the loincloth—and then I was completely, gloriously naked.

The sun shimmered in the momentarily hushed forest. The leaves shivered in the Douglas firs and madrones. I walked onward, ever so slowly slipping through shrubs, mosses, sorrels, and crumbled wood the color of devil’s food cake mix.

For the first time I really smelled a forest: the sweet and glorious rot of it, the chlorophyll and disintegration, the soapy scent of a ceanothus plant, the invigorating tang of fallen redwood needles. Tree limbs creaked like timbers at sea. I could feel the circular motion of air molecules scrubbing up and down my body like invisible loofahs.

The trees gave off a mentholated scent, which felt sharp, almost painful, in my nose. Planes flew out of San Jose airport and passed a few thousand feet above me. Hearing the rush of their engines and watching their vapor trails only added to the thrill of my isolation.

I took care with every step. Piles of leaves might conceal hollows where I could fall and wrench my ankle. I was relieved to come across my half-built debris shelter, which rested against a long and rotten redwood log. It was about seventy degrees outside. Every time a breeze passed through the woods and ruffled the remaining hairs on my head, my alertness sharpened.

A blue fly descended on me and nibbled the dead skin at the end of my index finger. It meant no harm. I did not kill it. Glory beams fell from the sky and lit the flat space at the bottom of a steep hill. I took a good long look at this lovely unloved place. This was the first time a campground really felt like mine. But this was no time to get sentimental. When that ball of fire sank below the horizon, I would have to be sealed inside my little shelter without a flashlight. Robin had told me that the moon tonight would be “sliver to none.”

I distracted myself for a few blissful moments, making a spear thrower out of rocks, twigs, and grass and hurling projectiles at the lifeless toy squirrel. Bam! I scored a direct hit. After building up a thirst with my atlatl tossing, I put the squirrel back on the rotten log and went up to Badger Spring. A beetle scuttled past me, a suit of black armor protecting its squishy parts. Everything I stepped on or brushed against was so much spikier and sturdier than I was.

Soon I found the long, dark slit that contained the spring. I arrived at the spot where water burbled up from beneath a rock overhang. There, in the shade, I sat down apelike in mud. The water was sugary sweet and had a zinging mineral aftertaste. I dribbled water across my scalp. “Oooh la la!” I cried. I got down on my haunches and settled on the soft, dusty ground, trickled water down my chin—and that’s when I heard the buzzing. Thinking at first that it was my fearful imagination or early-onset tinnitus, I ignored the sound until the humming got louder and more insistent.

In an instant the wasps were everywhere. In my defense, this was not one of those classic breast-shaped wasp nests, those bulbous, papery ones that dangle from tree branches. Burrowing California yellow jackets congregate in hollows and tunnels. They have enormous colonies and protect them aggressively. I managed to pluck one wasp off my shoulder and smash it on a rock. I had no way of knowing that my defensive violence would only worsen the situation. Lynn Kimsey, a professor of entomology at the University of California at Davis, told me after the fact that squishing a yellow jacket “releases all kinds of body odors” from the dead creature. If you’ve already disturbed the nest at that point, as I had done, the agitated insects will recognize the odor of their dead or damaged comrade. The smell of its broken body will “recruit” other wasps against you.

“Running is the only solution, because you will get stung a buttload of times if you don’t,” Kinsey informed me.

Angry yellow jackets, if so inclined, will chase you two hundred feet. I tried to escape, but did not go fast enough. The stings came all at once—thwock, thwock, thwack!

It felt like someone was splashing boiling broth on me. The corrosive liquid pain spread across my neck and shoulders, upper stomach area, hips and abdomen, but not—thank God—anywhere below my waist. By the time I reached the campsite, the little demons had stung me seven times. I was getting woozy; the forest was starting to wobble. I lay down in the cool soft dirt and rolled around for a good long while in pain, pressing clumps of earth against the swelling lumps on my neck and abdomen. At least the wasps had tired of tormenting me and returned to their hideaway. I moaned a lot, which did no good at all. My breath came up short, ragged, and labored. I could feel a great pressure bearing down on my chest. My legs seemed to be made of gelatin.

I wanted to get the hell out of there, but I could barely move; even in the daytime, with that much poison in my system, there was no way I could safely negotiate the half mile of steep, slanting, potentially neck-breaking stretches between here and Hihn’s Mill Road. All I could do was lie there in a panic, hyperventilating, taking hits from my Xopenex inhaler, trying to open my airways, and every so often glancing at my useless cell phone, which I’d brought just to photograph my campout for anyone who needed proof. I watched the SEARCHING FOR RECEPTION message flashing on the upper right side of the screen.

I was much too hyped-up and dizzy to think of anything but my own escape from this situation, and what I would do if more wasps decided to sting me. After a while, I took some cold comfort in the knowledge that Joseph Knowles’s first day in the woods was also painful, lonely, and dangerous.

In the first few hours of his campout, cold rain washed over his naked body, and there was no escaping from it. He crossed Bear Mountain, bare and shivering, arrived at Lost Pond, and soon had his first taste of real suffering. Brambles and bull thistle tore his skin. He limped through the underbrush, bleeding. None of the hype or his adoring fans could help him now. “My legs looked like they had been in a fight with a wildcat, to say nothing of how they felt,” he wrote in a birch bark missive to his waiting public.

That night, he tried and failed to make a friction fire; the wood was too moist. He had no food, and no shelter to keep him out of the dampness. Knowles jogged through the woods all night long to keep his blood moving and to stay warm. “I must have run miles that night,” he wrote.

He was so pumped up with adrenaline that he didn’t feel sleepy. Just to pass the time, he found a tree limb and did some chin-ups.

“Daylight came very slowly,” he reported.

As Knowles found out, time is relative when you’re naked in the dirt. “What time is it now?” I wondered as I lay against the log, the stings still throbbing on my neck and on my sides, my head resting on a pile of leaves. My thoughts turned to something Robin had told me during our intensive training sessions: Calm yourself. Go to Owl Eyes. Focus on the middle distance. Pay attention to any disturbance or change or motion you see. Pay attention to the softest sound you can hear. Having no other choice, I tried Robin’s method. After a while, my thoughts settled down, and my airways seemed to open up again. It was working. But just as I was entering a kind of limbo, made possible by a combination of self-hypnosis and a soporific dose of wasp poison, I noticed a flash of yellow.

A yellow jacket landed on the rotten log right next to my head.

She was perhaps three feet away from me.

“Go away,” I whispered. “Please get out of here.”

But she would not move.

I forced myself to stay motionless, and the wasp remained there on the log, an inch or two away from my useless squirrel toy. I considered taking hold of a nearby piece of wood and squashing the wasp, but it was much too risky.

Five minutes passed. The wasp still wasn’t moving. Maybe she was building up her energy to attack me better.

Without knowing why, and because there was nothing else to do, I forced myself to take a good hard look at her. (The aggressive attackers in any yellow jacket colony are females.) Her girlfriends had all gone home by then. It was just the two of us. The wasp began to walk up the log. She looked wobbly. Perhaps I’d hurt her on my flight back to camp.

The yellow jacket twitched her antennae and settled down again. I’d never seen one close up like this. I was surprised at how damned pretty she was: yellow patches, racing stripes, black circles down her body, the delicate piping between her thorax and abdomen, and wings I could see right through. Her eyes were black and glossy. I remained that way in my cradle of tan oak leaves for a while, just staring at her. No detail was out of place. I marveled at her perfect stinger, the downy tufts on her head, and the branching lines on her wings.

I don’t know how long I ogled her in this fashion. Do wasps sleep? This one seemed unconscious. Now was my chance to pick up a rock and end her life, but I didn’t see the point. I grew sleepy and briefly napped. When I woke up, the yellow jacket was gone. Such was my loneliness that I wished she’d come back. She had gone in such a hurry.

It was getting dark. My hunger rumbled through me, but I had nothing to eat but redwood sorrel, which I stuffed into my palm, rolled up, and covered with even more redwood sorrel, pretending the glob of green mush was a chicken burrito. Time to complete the shelter. I was barely cognizant enough to follow Robin’s basic instructions.

Robin Bliss-Wagner gave me a precise and elegant blueprint for building a debris shelter.

When I call this thing a “shelter,” I am being too kind. Really, it was just a heap of forest vegetation piled beneath and on top of me. It was fortunate that Robin and I had started this project with a few dozen armfuls of leaves during our “shakedown hike” the week before. To complete this glorified haystack, I spread my cotton half-sheet on the hill above camp, filled it with leaves, lugged it back, and repeated the process until I had a five-foot-high, seven-foot-long pile of duff and leaves that would serve as a mattress. This bedding would elevate me off the ground, saving my body heat and serving as a natural Therm-A-Rest.

In the two-foot-wide space between the pile and the rotting log, I fashioned a separate seven-foot-long, warm, thick “side pile” of leaves that I would pull over myself to use as a comforter, smothering me. In other words, I would be part of a sandwich: two piles of duff were the bread slices and I was the lunch meat. In theory, my trapped ambient heat would stop me from getting chilled. I had to force myself to lie down naked on the “mattress” pile; it was quite scratchy and itchy. Loose twigs twisted into my side.

Now came the tricky part: getting into “bed.” First I covered up my face and head with the cotton sheet. Then I reached into the “comforter” pile and pulled the whole thing on top of me.

I was buried alive. I pushed up from the top of the comforter pile, pulled away the cotton sheet, and made a sort of blowhole, with my eyes, nose, and lips sticking out of it. Immediately I felt claustrophobic. I was going to have to sit there like a mummy in a sarcophagus all night long. The wasp stings still burned and itched, but I tried not to rub or scratch them; if I so much as twitched or tossed in my sleep, the pile was going to fall off, leaving me exposed. Still, the shelter had its advantages. Considering there was nothing to hold it together, no blanket securing it, no overstructure or framework of any kind to stop it from slipping apart, it did a fine job of keeping the elements away from me.

If my numb nose was any indication, it was getting nippy out there. There was something lovely and intimate about this sleeping arrangement. I was part of the forest floor and was not sealed away from it. It was surprisingly warm. But the wasp poison kept moving through my veins; my neck still ached with it. Perhaps it had even leached into my brain.

As night fell, I looked up into the forest canopy, high in the redwood fairy circle, and saw an inexplicable presence in the boughs: a glowing silvery substance that looked like a bunch of mysterious grapes, each dangling on a phosphorescent tentacle of fog.

The ghostly grapes shone from the inside. What the hell was that, I wondered. Was it alive? Was I having a rhapsodic vision?

The more I stared, the more the vision intensified. This was not an effect of the light; the sun was gone. Yet the gleam grew and flashed. Perhaps it was a group of spirits stuck in the branches—lost souls up there. I wished I understood what that quavering thing was. I’ve spoken to some naturalists since my campout, and they’ve given me all sorts of theories. Perhaps it was a colony of glow-in-the-dark mushrooms. Or maybe it was a bunch of banana slugs mating. But why would fungus quaver in the branches like gelatin and appear to float in midair? And why would orgiastic gastropods flash and glow in the night? I can’t even explain it away as a hallucination, simply because I sat there looking at it for so long, thinking about it, considering it, judging it, and yet it held its shape for half an hour.

This photo was taken in a forested area of Santa Cruz during one of my one-on-one wilderness skills workshops with Robin Bliss-Wagner. This is a preliminary version of the debris shelter that I would later build in the Soquel Demonstration State Forest. Those are my feet sticking out of it.

Then the night began to eat away at those glorious glow grapes in the trees. “No, no, don’t go away,” I called out to the mass of ectoplasmic goop. “Stay right where you are. Please don’t fade away! I have no other light.”

It was no use.

One by one, the orbs extinguished themselves.

Soon the darkness was absolute.

Robin was right. The moon was just a fingernail.

The night grew blacker and I buried myself ever deeper in my debris shelter. As I settled in, I tried to find comfort in its musty, minty smell and its shape, which had responded to my form like a Posturepedic pillow, the material yielding to the contours of my body and creating a warm pocket of air around me.

I liked to think Old Joe Knowles would have been impressed with what I was doing. He, too, was able to recover from his initial struggles in the forest. The morning after his bad first night, Knowles “envied the hide” of a nearby doe. “I could not help thinking what a fine pair of chaps her hide would make and how good a strip of smoked venison would taste a little later. There before me was food and protection, food that millionaires would envy and clothing that would outwear the most costly suit the tailor could supply.” Knowles spared her life, though, but only because the Fish and Game Commission, to his great annoyance, had refused him a hunting permit. Like me, having to struggle just to find a legal place to do my campout, Knowles chafed at bureaucratic hassles. How could mankind get primitive with modern rules standing in the way? “The first men of the forest were not handicapped by laws from an outside civilized world!” he snorted.

That second day, he managed to build a little dam and trap a few lethargic trout, which he caught but had no chance to eat; after he decided to store them in a stream until he figured out how to make a fire, a hungry mink came along and gobbled them. Knowles’s legs and feet were in agony, but he calmed his thoughts and found some witchgrass, a fibrous weed with fuzzy stems. After picking as much of the plant as he could, he wove a dense mat, which he then fashioned into leggings, and used “the lining bark” of trees to make a pair of soft moccasins and a surprisingly comfortable shirt.

After a while, Knowles was able to make a fire to drive away the clouds of mosquitoes. Later on, he would admit to feelings of total desolation. “I did not experience any physical suffering to speak of, though I did suffer greatly in another way,” he wrote in his memoir. “My suffering was purely mental and a hundredfold worse than any physical suffering I experienced … It never occurred to me that I might be lonely … Time and again, those mental spells were almost too much for me. At those times I would vow that I would leave the forest the very next day.”

Sometimes the temptation to stop the campout maddened him, especially on the day he ran into a backcountry guide who recognized him. “Hello, Joe,” the man said. Using every bit of his resolve, Knowles walked the other way. Every time he was just about to give up, a thought would come to him: “Here is a chance to show that you are a man.”

As the days progressed, he became glad he hadn’t quit; he soon had some bragging points for his readers, including the yearling bear he caught in a deadfall trap. “I finally landed a blow on the bear’s head that put an end to him,” Knowles wrote on one of his birch bark scribbles. After preparing the hide, he now had a nifty robe. Never again would he be the Naked Man of the Woods.

The readers of the Boston Post adored this story so much that Knowles tried to outdo himself with every dispatch. He described an epic battle between two moose, and wrote about the day he stumbled across a still-warm deer, killed by a wildcat, supplying him with an unexpected windfall of venison and “an extra skin.” Later, he continued to embrace his circumstances, dining on flame-roasted frogs’ legs, hazelnuts, and wild onions, and shooting stone-tipped arrows with an ironwood bow tied with sinew. At one point, Knowles claimed to have ambushed another deer, tackled it, grabbed it by the horns, and snapped its neck with a quick twist.

Readers went wild themselves. By the time his experiment neared its end, Charles L. Wingate, the Sunday editor of the Post, had every reason to be glad they’d devoted so much print to Knowles. During Knowles’s two-month ordeal, the newspaper’s daily circulation more than doubled to north of four hundred thousand copies, the Post claimed.

Knowles was a superstar when he returned from the woods on October 4, 1913. Before the adventure, he’d promised to emerge from the forest dressed from head to toe in natural materials—and so he did. Not only that, but he was thirty pounds lighter, looking like “half-man, half-bear, with his matted hair, skin dark as an Indian’s, fur-lined chaps and bearskin cloak,” according to American Heritage.

When a startled teenage girl saw him walking on railroad tracks in Quebec, he looked like a picture she’d seen of an ancient man. Knowles grunted at her and started crying grateful tears. “He smiled, and the girl saw the gold flash in his teeth,” the Boston Post reported. “‘He is a real man,’ she said to herself.”

When Knowles embarked on a triumphant whistle-stop tour to meet his readers, rolling south through Maine and bound for Boston, the people could not love him enough. They yelped at him and tore his clothes.

Nearly a quarter of a million people packed the streets of Boston to greet him in his smelly, homemade bearskin robe. Women reached out to caress his muscles. Policemen had to drive back a few Knowles fanatics. “Great work, Joe!” his fans cried out. “You’re all right!… You’re my bet!”

His newfound status must have seemed permanent to him. He’d worked hard to become famous, and now the job was done. No more neck breaking. No more creature clubbing.

Yet Knowles’s public reputation was about to take an even worse drubbing than the yearling bear in his deadfall trap.

* * *

It was impossible for me to know what time it was when I reached for my flashlight and then remembered that it was down the hill in the Chickenshit Tree. I could see nothing, not even the outline of the trees in the fairy circle around me. I could hear all kinds of crackling and movement. I imagined cougars encircling the shelter, smelling me, seeing in the dark, brushing against the debris pile, pawing it like house cats in a litter box. I couldn’t believe how hard I’d fought back against my wife so I could have this experience in the woods. How I wished I was back at home, thwarted and bored and reading Cook’s Illustrated.

As the evening wore on, I wished the shelter were so much bigger. How I wished it had rooms! I pretended my modest duff pile was an Arts and Crafts–style mansion five stories high with a hundred corridors and seventy-seven secret entrances; for hours, I thrashed my feet around in the pile and fought an inexplicable desire to bolt from the shelter and run through the jungle. Was it midnight yet? Nine p.m.? Four in the morning now? Six a.m.? Was time running backward?

I tried every trick to pull the morning closer. I recalled my favorite parts of Moby-Dick. I cycled through John Updike’s entire Rabbit tetralogy for what seemed like seventeen hours. Then another twelve hours seemed to pass. When I opened my eyes, the sky had only grown darker.

Then I heard running footsteps just behind me. Something was bumbling through the underbrush, coming right toward me. Twigs and branches broke to the side of me. I heard a crunch in front of me. The ground trembled. Too scared to shriek, I cringed into the duff pile and tried to hold my breath. Whatever you are, please don’t see me, don’t even smell me. Something large was walking through the camp, breathing deeply, and padding in front of me. In a moment I heard the footsteps again, in retreat, returning the way they’d come, to the woods above my shelter.

For the rest of the night I tried not to move at all. I kept waiting for the creature to return. I dared not fall asleep, not even for a moment. But there was no denying it; my bladder was full. The urge to pass water was so terrific I could contain it no longer, though I feared compromising the shelter’s integrity. Without a choice, I crawled, shivering, out of my pile of duff and balanced myself with shaky legs on the rotten log.

I did this in a frenzied manner, knowing that something with infrared vision might pounce upon me. Once my bladder was empty, I scrambled into the duff pile again. The early morning chill had sunk into the shelter’s heart, compromising the insulation bubble I’d made with my trapped body heat. Besides, in my haste to remake my shelter, I had somehow grabbed several clumps of the redwood duff upon which I’d relieved myself, adding an unwelcome rank dampness to the creeping chill. As I sat there for hours, marinating slowly in wet hay, with lumps of deer shit sticking to my entire body and dozens of pinching splinters puncturing me all over, my wasp stings pulsating, I began to wonder if I might do well to take up another hobby.

The reputation of the Nature Man crumbled almost as quickly as my shelter did that night.

* * *

In late November, when Knowles was stuffing his pockets with as much as twelve hundred dollars per week for his lectures and live camping demonstrations, the Boston Sunday American, perhaps resentful of the Boston Post’s enormous success with its Knowles coverage, ran a devastating exposé.

The headline read “The Truth about Knowles: Real Story of His ‘Primitive Man’ Adventures in the Maine Woods.” The newspaper claimed that almost every aspect of Knowles’s history-making campout was a big fat lie. Naked? The article said he’d kept his clothes on. All alone in a handmade shelter? The reporter claimed that Knowles had hung out in a cabin with an accomplice who helped him fool the public, and had even enjoyed the company of a female admirer. The reporter also said that Knowles, who made a big show of getting fined for killing game out of season and having a nature warden come down on him, had even fibbed about killing the bear that yielded his bearskin robe. The reporter quoted an eyewitness who said that someone had paid twenty dollars for the bearskin and handed it over to Knowles. According to the informer, the skin had four noticeable bullet holes. Quoting the witness, the writer said the deadfall trap was so shallow that it never could have contained a bear, or even, for that matter, a small kitty cat.

In those days before the Internet and “going viral,” the damage was not immediate. Knowles went ahead with a popular vaudeville tour. He used the stage to re-create his survival feats. His hastily written book about his ordeal became an instant best seller. Yet the accusations infuriated him; he filed a fifty-thousand-dollar lawsuit against the Boston Sunday American. Then, in an attempt to challenge the story about the bearskin, he placed a sleepy, and possibly even hibernating, bear in front of a crowd of onlookers, beat it to death, and then skinned the poor thing with a sharp piece of shale for good measure.

In an act of even greater desperation, Knowles attempted a “do-over” of his entire survival trip, this time up in the Siskiyou Mountains in the Pacific Northwest with two esteemed observers, including the same famous anthropologist who once studied Ishi, “the last wild Indian in North America.” In the buildup to the 1914 redo, Knowles showed off some startling and undeniable displays of primitive survival skills. On July 15, close to his departure day, he jumped into the Rogue River and caught a three-pound fish barehanded, to the amazement of his observers.

Now Knowles faced a problem far worse than any doubts about his authenticity. Suddenly, the world no longer cared. The San Francisco Examiner put the war between France and Germany on the front page and knocked Knowles into the back section, next to an advertisement for a digestive aid for tots.

Knowles kept making progressively sillier bids for a major comeback, including a bizarre plan to do a survival campout in the Adirondacks with the beautiful starlet Elaine Hammerstein, first cousin of the legendary Broadway lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II. The delicate Elaine, however, was no wild Victorian lady, and the campout collapsed before it even began.

So Joe Knowles, like “Adirondack” Murray before him, waddled his way into utter obscurity.

In the late 1930s he was living a low-key life in the Pacific Northwest—for a while, he served as a Boy Scouts leader, teaching his young “striplings” to survive “Without tent, kit, or provender”—when another bizarre and unwanted development yanked him right back into the public consciousness. On June 18, 1938, the New Yorker wrote a “Where Are They Now?” column about Knowles, claiming he had pulled off the “hoax” with a cynical mastermind who’d plotted out all the exploits in advance for maximum publicity, using a scheduling calendar. “Tuesday, kills bear,” one entry read. By the time the Nature Man died four years later, his schmuck-ness was well established. “All of the two hundred thousand people who gathered at North Station to greet him [upon the completion of his campout] are now probably dead, too, and his book is available in only a few libraries,” noted Boston magazine in its wistful remembrance of Old Joe.

* * *

In the darkness of the Soquel Demonstration State Forest, as I twisted around in my makeshift shelter, I wondered why it was so easy to remember Knowles’s self-proclaimed feats of survival and so hard to remember allegations that he was a lying crumb bum. Why did I have a vested interest in believing Knowles was real? Why go through so much trouble to celebrate a possible fraudster?

For one thing, it must be said that Knowles, whether or not he lied about his Maine camping trip, had the skills to pull it off, as he proved with his Siskiyou do-over. I also believe that the issue of his alleged fibbing and shortcutting is less important than the attention people lavished on him in 1913. Knowles matters to me because he turned camping into front-page news. He showed just how thoroughly the fascination with outdoor life had spread to all corners of America, including the working class, which comprised the bulk of the Boston Post’s readers. In his own deranged way, Knowles, in creating such adulation and furor, proved that camping in America had truly arrived.

Roderick Nash, in his classic book Wilderness and the American Mind, a sweeping look at America’s developing views about the outdoors from the Puritans onward, writes that Knowles “added to the evidence suggesting that by the early twentieth century, appreciation of wilderness had spread from a relatively small group of Romantic and patriotic literati to becoming a national cult.” Less charitably, Nash also says that Knowles’s evanescent celebrity “was just a single and rather grotesque manifestation of popular interest in wildness.”

Even if Knowles was sometimes less than honest, he was nevertheless ahead of his time. As the historian James Morton Turner has pointed out, before there was such a thing as a “wilderness movement” in America, “Knowles proposed setting aside ‘wild lands’ and establishing outdoor communities where Americans could retreat from the ‘commercialism and the mad desire to make money [that] have blotted out everything else, [leaving us] not living but merely existing.’”

That alone is reason to commemorate the man, as flawed as he might have been.

* * *

Back in the sticks, the heat, miraculously, returned to my shelter. Soon it was warm and cozy again, and when first light came, steam rose from the top, just as Robin promised. The first chance I had, I burst out of my shelter, tied the cotton sheet around my waist, grabbed the plush squirrel off the log, dug up my running shoes and loincloth, put them on, and crashed through the forest.

Once on Hihn’s Mill Road, I trudged uphill toward the parking area, not making much haste, because I now remembered the words of the cyclist who warned me about the burgling “crackheads.” I knew what I was going to find when I got to the car: a broken window, the trunk popped wide open, the tires slit to pieces.

Sure enough, when I arrived at my parking place, the car, as I suspected, was tilted at a strange angle, with broken glass all around it. What rotten luck! When I got closer, however, it became clear that the broken glass had been there already, and the car was parked at a sharp angle. I felt so grateful and happy to have survived my ordeal. I was even thankful to the druggies for sparing my car that night. “Happy Knowles Day, crackheads!” I shouted as I opened the car door and got inside.

Safely out of the forest, resting in my car, I could look at that campout as something other than a nightmare. Out in my shelter, I had been miserable at times, but at least I was uncomfortably alive. Thoreau went to the woods to live deliberately, to front the essential facts. In my case, the campout, if anything, had been a little too deliberate. The experience was so intense, so unfiltered, that it short-circuited my brain and took me into an imaginative dream space from which I could not escape until sunup. Alone with no clothes, I’d ended up in a world where a yellow jacket might seem vulnerable and beautiful, maybe even a little bit sexy, and ghostly grape shapes glowed in the dark for reasons that defy easy explanation. Lying in my car, I missed the glow grapes and wished I could see them again. I knew they would never show themselves unless I stripped off my clothes and lay down naked on a forest floor, which I would never do again. Because, let’s face it: the evening was, for the most part, a fright, with brief interludes of mystical experience and inexplicable visions. At least I got through, and answered my burning question: Is it possible to camp out naked and with nothing? Yes, indeed it is possible, but if you do it, your mind won’t be the same. Never again will you fix the boundaries between fantasy and reality with such certainty, or question the utility of socks and underwear.

Perhaps I didn’t emerge from the woods tanned and well muscled, with crowds of people waiting for me like Knowles; nor did I have a crude deer-horn knife clinging to my waist on a belt of sinew. Yet I am in perfect alignment with Knowles when it comes to our overall attitudes about camping in the nude. “Above all else,” he once said, “I want to emphasize that living alone in the wilderness for two months without clothing, food or implements of any kind was not a wonderful thing. It was an interesting thing; but it was not wonderful.”

Knowles, in spite of his Stone Age trappings, was as modern as could be. While he made a big show of using ancient techniques to survive outside, he slyly acknowledged the twentieth century by tapping into the mass media, exploiting the public’s interest, and turning himself into a big star. He was not the only American to display such contradiction. Right around the time of his then-infamous, now-forgotten campout, another adventurous group was pulling off a surprisingly similar feat. Paradoxically, these men and women tried to harness the power of technology to help them flee the modern world, using a contraption that would forever transform the camping experience.

That invention was called the automobile.