They talk about a woman’s sphere, as though it had a limit. There’s not a place in earth or heaven. There’s not a task to mankind given … without a woman in it.

—Kate Field, journalist, nineteenth-century camper

In 2008, I was in Portland, Oregon, on a book tour to support my Pacific Crest Trail memoir, The Cactus Eaters. My talk was set to begin at 7:00 p.m., and I was getting twitchy, because it was 6:45, there were forty seats, and all but ten were empty. I hid in the children’s section and watched the bookstore staff round people up and practically shove them into the folding chairs. Five minutes before 7:00, fifteen more people sat down. Two drew my special attention: a stringy-haired teen who sat in the center of the third row, only to bury his face in a manga book, and an athletic blonde who appeared to be in her early thirties. She was wearing, if memory serves, a Polartec-type dark fleece zip-up jacket. I enjoy guessing the occupations of audience members to amuse myself and ease my nerves. During my reading, I picked up on this woman’s stillness and watchfulness, and her talent for deep listening. She was most definitely a child behavioral psychologist, a career guidance counselor, or an animal trainer. After the talk, she waited in line to have me sign her copy of my book.

“You live and work around here?” I asked her, eager to test out my hunch about her job.

“Yes,” she said. “In Portland.” She mentioned her husband and two young children.

“What’s your work out here?”

“I’m a writer.”

“Cool. Part time?”

“Full time,” she said, with just a little bit of an authoritative edge to her voice.

“Really? So cool. What’s your husband’s job?”

She told me he made documentaries.

“Oh, my goodness,” I said. “And you can survive with those jobs?”

“So far,” she said.

“Nice. What’s your name?”

“Cheryl Strayed,” she said.

“Really?” I said. I’d read a bunch of her work. I’d even studied her essays in graduate school. But this healthy, seemingly centered woman looked nothing like the pale and haggard vision I’d conjured from her essays, which mentioned hard living and drugs. “You’re not what I expected,” I blurted out. She laughed, and told me she had similar reactions from time to time. Certain readers seem to expect whips and chains, she told me. “I’m a soccer mom!”

I stopped talking to her for a moment, walked up to the live microphone, and addressed the stragglers in the crowd. “Hey, everyone, guess what? Cheryl Strayed is in the house. Cheryl Strayed, the writer? She’s got skills!”

She smiled indulgently. A couple of people gave me blank stares, then went right back to browsing the aisles. No one had any idea who she was.

We wound up talking for a couple of hours at a Chili’s restaurant in the charmless mall that contained the bookstore. Cheryl Strayed ordered no food or beer. She accepted one limp french fry after I urged her to try it. She wanted to tell me about a book she was drafting. It involved a long walk on the Pacific Crest Trail. From the sound of it, a lot of the book had to do with her mom and her past. She hadn’t decided how much weight to give the trail, or how the pieces of the narrative were going to talk to one another and fit together. Just before my sloppy meal was over, she looked at the remains of my terrible burger. “Don’t you know that Portland is one of the great food cities of America?” she said.

“Now you tell me,” I said, feeling the onset of a stomachache.

We continued our Chili’s conversation over the next few months, through a series of long e-mails. She gave me more information about her work-in-progress and confessed a touch of nervousness. How were people going to respond to her work? I came to believe that certain testy members of the Pacific Crest Trail community and perhaps the rest of America would gang up on her. Even now, in the twenty-first century, the story of a woman camping and hiking alone feels like a provocative gesture to certain people, a jab at the status quo. “Wild is certainly about hiking the PCT,” she told me during one long online missive,

but it’s also really very much a memoir about my life before the hike. There are long, long “flashback” passages, and what goes on inside of me is in some ways more front and central than the trail (though of course the trail is huge in the book, too—when you read it, you’ll see what I mean). Plus—oh, and this is going to drive those PCT purists nuts!—I did not thru-hike the trail. I hiked about twelve hundred miles of it. That’s a long way. How this idea formed that if you didn’t hike the whole thing you somehow didn’t really hike the trail is utterly absurd. I never intended to hike the whole thing. I set out to spend about a hundred days on the trail, and that’s what I did. It was hard, amazing, and life changing. I wasn’t prepared for the hike (this too will incite the hiker purists!), but I learned a lot. And that, of course, is the story. Or at least part of it.

I sent her a long and sympathetic e-mail, and she sent me one in return when I vented about my experiences with online haters and trolls. Years passed. We fell out of regular e-mail and Facebook communication. When her book was released, it did not turn out to be the disaster I worried it might be. It did not get buried beneath a pile of hatred and male opprobrium. It became one of the best-selling memoirs of all time, and certainly the best-selling book that devotes so many pages to an American woman’s solo camping adventure. As the book climbed to the top of the list and was made into a feature film, it occurred to me that Wild was lucky to have been published in the twenty-first century. Of course, the huge success of this book was much more than a question of its timeliness. Strayed wrote a beautiful, candid, and unsparing work, an unsentimental and gripping story of redemption in the wilderness. But it also occurred to me that if she had been born in, say, 1819, the work, regardless of its quality, would have enjoyed a small private printing at best. At the time her book came out, I had been reading my way through a teetering pile of redemptive wilderness memoirs dating to the 1830s. It occurred to me that the basic shape and setup of Wild—a troubled Romantic travels into the wilderness seeking not an escape from the world but a different way to engage with it—is part of a long-standing literary tradition. It’s just that this redemptive journey was, until recently, an exclusively male and elitist endeavor. It occurred to me that my prediction about the anti-Wild backlash was out of step with twenty-first-century reality: America loves an underdog, and I doubt Wild would resonate with readers in quite the same way if it were about a male trust-funder slack-packing the trail with an entourage of mules and support vehicles. Wild is provocative in part because it rewrites and dramatically recasts a familiar template.

Back in the 1840s, the Reverend Joel Headley helped create a popular model for the find-yourself-while-camping-in-the-woods genre when he became well known for writing about an “attack on the brain” that drove him into the Adirondacks. Looking at the notoriety Headley’s book received, I had to wonder: What about the women and their attacks of the brain? What did they do? At a time when feminine and weak were synonyms, and men considered themselves masters of the camp, how did these women cope with the double standard without going crazy? What, if any, tentative steps did they make to nudge America just a little bit closer toward Wild, toward the notion that women could be considered adventurers outdoors in their own right, strong and independent and not just the helpmates of male campers?

The more I snooped into that period, the more it became clear that women were not just sitting back in their parlors or sprawled (genteelly, of course) on their fainting couches and meekly accepting the idea that forests belonged to male explorers. I was surprised to find that many American women refused to stay home while the men went off and set up their “fixed camps” in the forest, cooked stews, erected wall tents, and jacklit deer. Women dragged themselves through canyons and explored slippery caverns with sputtering lanterns in their hands and flat-bottomed shoes on their feet.

There are photos of women staring down from the tops of remote mountains in the Cascades with footwear that would be hazardous anywhere, even on a city sidewalk. They have clunky walking sticks and rifles in their arms and smiles on their faces. One iconic photo from 1909 shows a group of adventurous women in full-length Victorian dresses and ridiculous cone-shaped hats standing on Pikes Peak and holding aloft a great big billowing sign reading VOTES FOR WOMEN. This photo op was staged years before a woman’s right to vote became the law of the land in the United States. Camping and climbing women regarded the woods and the mountains as more than just recreational space. They were also places where women could make a political statement, raising a feminist banner on top of a giant phallic symbol. “The history of American women is about the fight for freedom, but it’s less a war against oppressive men than a struggle to straighten out the perpetually mixed message about women’s roles that was accepted by almost everybody of both genders,” wrote Gail Collins in her America’s Women: 400 Years of Dolls, Drudges, Helpmates, and Heroines. Such was the case in the woods, where women learned to write their own rule book.

This scary peak in western Washington would frighten away most campers, but it could not stop this mid-nineteenth-century woman from scaling its hazardous heights, while decked out in a smothering dress and insensible shoes and risking accidental suicide by firearm.

It took a long while for those women to make headway in the forest. When recreational camping started in this country, it was like one big frat house. Men flocked to the forest so they could spend time in the company of other men. Proper ladies were told to stay at home. In the years after the Civil War, affluent women had a certain amount of power and social status in luxurious resorts and upscale hotels, often to the resentment of their husbands, but their status in the woods was lowly.

America’s population was less than 40 million in 1870. By 1920 the number had climbed to 105 million, and most people were living in cities. As the feminist historian Nancy C. Unger points out in her book Beyond Nature’s Housekeepers: American Women in Environmental History, only fourteen cities in 1870 had populations of 100,000 or more. In 1920 nearly seventy cities were that big or larger. In 1890 the superintendent of the U.S. Census declared the American frontier closed. Three years later, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner panicked men when he spoke about the loss of the frontier lifestyle, which Turner insisted gave Americans (read: white male Americans) their unique and rugged character, a certain coarseness and strength “combined with acuteness and acquisitiveness; that practical inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things … that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism.”

Men, pining for that idealized version of pioneer times, full of male camaraderie and minus the untidy parts such as typhoid, disembowelments by grizzly bears, and cholera, felt diminished and rootless. Mentorships and apprenticeships were dying. Fewer men devoted their lives to craft traditions. It was possible to live out one’s whole life without milking a cow or making something by hand or setting foot in the woods. Not as many livelihoods were considered earthy and manly anymore. This was a time when American men feared any potential challenge to their influence and control.

Where could they go where they could swear and smoke and behave as they believed real men should behave, far from the efforts of women to control and “civilize” them? These men set out to make the entire outdoors into their private cigar lounge. Even the names of landscape features reflected that masculine desire. Mountains in the Victorian era were considered manly and robust, while lakes were female and nurturing. Water bodies were passive, reflective, and empathetic. Landmark names, therefore, fell in line with this idea. Often, the few exceptions to the rule were sexualized in rude ways—for instance, Twin Teats, Nellie’s Nipple, the Grand Tetons, and Squaw Nipple Peak. When someone dared name a peak in Inyo County Mount Alice, the name was quickly changed to something deemed much more appropriate for the times: Temple Crag.

Any sort of long walk was considered out of the question for respectable ladies. In those times, doctors commonly thought that exercise would sicken any female—a woman’s doing the equivalent of the Pacific Crest Trail would have qualified as madness or a form of suicide—even while books and articles claimed that outdoor activities could cure middle- and upper-class men of neurasthenia. Certain medical experts thought that such strenuous, sweat-inducing activities actually worsened hysteria in women, making them “delicate and high-strung, subject to fits of anxiety or even hysteria that could erupt at any time,” wrote Sheila M. Rothman in her book Women’s Proper Place: A History of Changing Ideals and Practices, 1870 to the Present. “By virtue of their anatomy, all women were susceptible and therefore had to avoid anxiety-producing and enervating situations.”

The prevailing women’s fashions, which emphasized bulky and concealing garments, added yet another layer of physical confinement. Women were more likely to be harmed just by standing around wearing the standard-issue clothing of the day—crushingly tight whalebone corsets and thick, misery-inducing skirts—than by climbing a mountain in more sensible attire. Their clothes were so restrictive that the pioneering female doctors of the time started to notice the side effects of Victorian fashion, among them, corset-induced “displaced or prolapsed uterus, atrophy of abdominal muscles, damage to the liver, displacement of the stomach and intestines, and constriction of the chest and ribs.”

Another strong disincentive to camping out was the fact that there was no such thing as a sanitary pad, Nancy C. Unger, a professor at Santa Clara University, told me when I called her up to discuss her book. “Most of the women out in the woods at that time were in their reproductive years,” Unger told me. “No wonder so many of them did not want to go camping. I get so impatient with the idea that women were too fastidious to go out there. They had to deal not only with their periods, but with this uber emphasis on women’s modesty, a pressure on them that men didn’t have to face. The first disposable pad didn’t come along until the 1920s. Instead, the women were forced to use rags, which were not designed for the contours of the female body. They move around. That’s why lots of women often took to bed for a couple of days when they were having their periods. The rags were inconvenient, and they were not disposable. If women camped, they had to consider laundering their rags and wonder: Will there be water in the campsite? Will it be raining? Where will we dry them?”

Fortunately, the second half of the century brought new opportunities for women in the woods. A few strong-willed men stood up for their right to be in the forest at all, including, as we have seen, the first great camping popularizer, William “Adirondack” Murray. Even women’s clothes became a touch less constraining. Out in the forest, starting in the late 1850s, a few daring women left their terrible corsets at home and donned ankle- or knee-length trousers called “bloomers,” that mid-nineteenth-century innovation that is stifling to contemporary eyes but was much more comfortable and freeing than standard-issue dresses. Women were also more likely to stop by a sporting goods store and pick up an “outing skirt” that they could unbutton down the front if they got too hot. Naturally, some men were shocked and disgusted to see such things, but for some women that was the whole point. “We learned … to wear our short skirts and high hob-nailed boots … as though we had been born to the joy of them,” wrote editor Harriet Monroe about a trip to California’s Kern River in 1908. The scandal felt wonderful to her. People acted as if she were “a barbarian and a communist,” she later boasted. Without those tight clothes pressing on their guts, women could even enjoy hearty flame-roasted food in the forest and stuff themselves for the first time.

Still, the clothing brought only a measure of freedom. If a woman camped in a party of men, she was supposed to fall uncomplainingly into the role of housewife, becoming camp cook as soon as the sun started sinking. Even if the women managed to have some burly adventures, they were expected to keep quiet about them. It was considered unseemly for ladies to talk about their feats of tramping and climbing. While Cheryl Strayed worried, many years later, that hiking “purists” (a predominantly male group) would feel she hadn’t hiked “enough” of the enormous PCT, Victorian camping women were, if anything, discouraged from writing about their acts of bravado at all. The more miles they walked, the more mountains they bagged, the more they were told to understate their accomplishments.

Some were forced to sublimate their desires by living vicariously through men. We’ve all heard of John Muir, but it’s a lesser-known fact that a strong-willed and super-smart woman named Jeanne Carr greatly influenced him. The wife of Ezra Carr, one of Muir’s professors at the University of Wisconsin, not only curated Muir’s reading list but also encouraged and helped shape his writing voice. She gave a sterling recommendation of Muir to Ralph Waldo Emerson, who ended up hanging out with Muir for a short while in Yosemite in 1871. Muir was her pet project, and she was Muir’s perfect audience long before he had a mass readership. He was always trying out ideas on her, and reporting back from campouts and explorations. Without Carr’s guiding hand, perhaps Muir would have lived all his days as an eccentric hermit in Yosemite instead of moving out of the valley later in the 1870s and changing the world. “As a feminist, [Carr] disliked many of the duties exacted from a housewife in High Victorian America,” wrote Stephen Fox in his book The American Conservation Movement: John Muir and His Legacy. “She hated fashion and housework … she felt her life ebbing out in little dribs and drabs … She envied [Muir’s] freedom … ‘Write as often as you can,’” she told him. “‘Your letters keep up my faith that I shall lead just such a life myself sometime.’”

But there was a surprising upside to being a wild lady of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Some women used male stereotypes of their behavior and interests to their advantage. “Botanizing” was considered an admirable pastime for women, so it gave women license to go sauntering into the woods and mountains. Bringing along a plant press was a kind of passport for them to go wherever in the wilderness they pleased. If a man came along and asked what on earth they were doing so far afield, these respectable ladies could whip out some of their dried rhododendrons and tell the man, in all seriousness, that they were advancing the causes of science and ecology. Since women were considered more virtuous and in tune with “Mother Nature” than men, they were among America’s first credible preservationists.

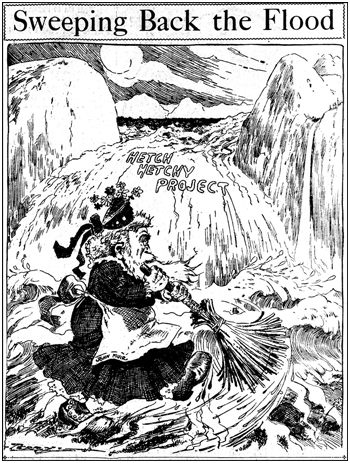

This association between women and preservation had its inevitable downside. Men who opposed wilderness could always twist around the image of female weakness and use it against any enemy who stood up to them. During the buildup to John Muir’s humiliating defeat at Hetch Hetchy Valley (the pristine area of Yosemite National Park that he attempted to save from a campaign to impound the Tuolumne River and create a new reservoir to serve San Francisco), development interests slandered him as “impotent and feminine.” In a political cartoon that appeared in the December 13, 1909, issue of the San Francisco Call, the great preservationist is shown in dowdy drag, desperately trying to sweep away the floodwaters of Hetch Hetchy with a dust broom.

There was only one way for adventurous women to deal with this strong link between womanhood and weakness. They had to ignore it. In the late nineteenth century, it became more common for all-female camping parties to head into the woods for fun. Starting in the 1880s, a boisterous group of “artistic, Avant garde” well-off female campers called the Merry Tramps of Oakland headed for the coasts and forests together in Calistoga, Sonoma County, and the San Gabriel Mountains of California. They were not exactly steely-eyed survivalists dragging themselves up Mount Hood. If anything, they qualified as America’s original-issue glamour campers, heading toward the forests in beautifully appointed Pullman cars with enormous suitcases, fine liquors, and comfortable bedding. This gleeful group posed for photos while holding hands, making a daisy chain around a giant Pacific Coast redwood. They slept on fine feather beds hauled into huge wall tents, with stacks of rifles piled in front of their vestibules. They hired small armies of Chinese cooks to prepare their breakfasts, lunches, and dinners. Yet even this escape to the woods could not let them flee all domestic responsibilities; there are photos of Merry Tramps wearing all their finery while stooped over a sinkful of dishes, soap bubbles floating as the women scrub and clean.

The San Francisco Call used this image to embarrass John Muir for his campaign to save Hetch Hetchy.

The Merry Tramps had safety in numbers—in certain photos, there are so many of them that not all of the campers can squish into the camera’s view—but other women preferred to travel in pairs or face the woods alone.

More than a century before Cheryl Strayed wrote about her encounters with strangers along the Pacific Crest Trail, including a run-in with a sexually menacing and boorish hunter, newspapers all across America wrote about the incredible camping and long-distance hiking exploits of thirty-six-year-old Norwegian immigrant Helga Estby, who lit out on May 5, 1896, from Spokane, Washington, on a walking journey across America, leaving her husband, Ole, and eight of her children behind on the farm. She and her eighteen-year-old daughter, Clara, both wearing heavy skirts, planned to walk thirty-five hundred miles to New York City on the promise of a cash reward; anonymous sponsors had put up ten thousand dollars and said the money was theirs to claim if they made it to Manhattan within seven months of their departure. Apparently their shadowy benefactors had something to do with the fashion industry, and were hoping Estby and her daughter would “prove the physical endurance of women, at a time when many still considered it fashionable to be dependent and weak,” wrote Estby’s biographer, Linda Lawrence Hunt. In an early instance of product placement, the sponsor also forced Helga Estby to wear a certain “bicycle skirt” for part of the walk.

Estby knew the risks on the road and in the forests. She was packing a Smith and Wesson revolver, some pepper spray, a lantern, a compass, and a map. Young Clara brought along her curling iron. The circumstances of Clara’s birth are still mysterious; Helga Estby became pregnant when she was only fifteen, which has led to speculation that she was raped while working as a housemaid. Helga and Clara Estby took lodging when they could, but they did a lot of camping on their transcontinental journey. This was not a vacation for them. The Estbys were lagging on their mortgage payments, and Helga Estby was trying to save the family farm, which had been threatened with foreclosure. When a newspaper reporter cornered Estby and asked why she kept walking on, “Well, to make money” was her pragmatic response.

Trying to avoid getting lost, they followed the railroad tracks on their journey to the east. They faced danger at every turn, but these were no women to mess with. A menacing vagrant shadowed them through the mountains near La Grande, Oregon, until Helga Estby finally pulled out her Smith and Wesson and blasted a hole through his leg.

The journey was an adrenaline rush for the mother-daughter team, especially when the two ended up staggering through the jagged lava beds and scrubland of southern Idaho. They slept out in the Red Desert of Wyoming, which was swarming with antelope and grizzlies.

They thrilled to the sounds of the night wind and narrowly escaped a gray mountain lion “as big as a man” that followed them for twelve miles. “Being acquainted with the animal’s traits, we knew they never attacked from behind and never except by running and springing upon a victim,” explained Helga Estby to a reporter. But the biggest danger was a robber near Denver, Colorado, who tried to attack the women, only to get a face full of pepper spray so painful that he fell to the ground and tumbled down a slope. “I knocked him down,” Helga Estby bragged later on. A gang of would-be assailants from Chicago had to beg for clemency when the women attacked them with bug powder. The mother-and-daughter team pressed on with their walk, and refused to give up, but a rude surprise awaited them at the finish line.

At the end of Wild, Cheryl Strayed meets the love of her life. Trail’s end was different for Estby. The sponsor cheated her and Clara out of the promised cash award on the flimsy grounds that they missed their arrival deadline in New York City by eighteen days, in part because Clara had fallen and hurt herself in Colorado. The two apparently had to beg for funds from a sympathetic railroad magnate just to get back home, and by the time they did two of Estby’s children had died of diphtheria.

Helga Estby and her teenage daughter Clara packing heat, holding a dagger, and getting wild in 1896.

Estby won no points for heroism, only public shaming and sour faces. She received no meaningful posthumous recognition until history buffs rediscovered her in the early 2000s. Linda Lawrence Hunt blames Estby’s long-standing obscurity on neglect, willful or otherwise. “She broke the central code of her culture, in this case that ‘mothers belong in the home,’’’ Hunt writes, speculating about the reason that Estby’s story remained untold, even within her own family, for seventy years. Or Perhaps Estby was compelled to silence herself because her trip was controversial and she did not wish to create more family strife.

Whatever the circumstances, Estby, unlike Strayed, did not have a chance to tell her story in detail—her letters and unpublished manuscript are now lost. Fortunately, some other camping women have left vivid recollections of their journeys into the unknown. One of the best is Kathryn Hulme’s wonderfully written 1928 outdoor memoir, How’s the Road?, which reflects on the newfound freedom women found in the outdoors because of the invention and mass popularity of the automobile. Suddenly women did not necessarily have to tag along on a macho campout in the high peaks of the White Mountains or the Adirondacks to get their taste of the wild (and scrub someone else’s dishes). Now their wheezing metal contraptions could get them to the edge of the wilderness unaccompanied or with other women.

In the summer of 1923, Hulme and her friend Tuny set out on a 5,444-mile cross-country auto-camping journey from New York City to San Francisco. Along the way, the America they saw seemed foreign and wild; the Wisconsin dells were a lingering frontier. “[P]oising on top of a hill, the head-lights focused on the brow of the next hill, [and] leaving the dell through which we were to plunge, a mystery of black nothingness,” Hulme writes. Deep in the Badlands of South Dakota, she and Tuny piloted a roadster named Reggie into a river but seriously misjudged the water’s depth and power. Rolling through strong currents in the deepening waters, the tires lost contact with the river bottom. Reggie began to float. “Liquid mud flew as high as the windshield,” Hulme wrote. “Reggie was swimming. Reggie was chocolate-covered from top to bottom. I had received a mouthful of gumbo [mud] when I shouted in midstream. Our license plates were obliterated.”

The territory of men was just as hazardous as any mud wallow or river bottom. Hulme and Tuny slept on prairies, in Canadian forests, and on mountain meadows in Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks, resilient in the face of bad weather, busybodies, and unbelievers. People in towns found it odd that two women would dare to auto-camp without men. Hulme mentioned the “kind, motherly” henlike women who accosted them in small towns and directed them, endlessly, to the nearest YWCA. When Hulme and Tuny got a flat in a small and isolated town, they had just barely started to fix it when four boys showed up out of nowhere and elbowed them aside without asking permission. “Tuny and I stood around looking helpless and grateful,” Hulme recalled. “It always pained us … Tuny and I were both good mechanics, capable of making any repair on the car.”

Granted, Hulme wasn’t backcountry hiking like Strayed, but one could argue that her auto-camping journey was a small step in the direction of a twenty-first-century woman’s solo hike. The author reveled in the freedom of the outdoors. Like Thelma and Louise in the successful 1991 eponymous film, Hulme and Tuny were bold, independent, on the lam from boredom, and fated to run into many of the same problems that bedeviled the characters played by Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis: the endless come-ons of confidence men (most of them not as good-looking as Brad Pitt), sexual menace, and constant unwanted offers of help. “We had many experiences with the ‘assisting’ man camper who thinks that when a woman gets anything more complicated than an egg-beater in her hand, she is to be watched carefully,” Hulme said more than ninety years before Rebecca Solnit published her nonfiction book Men Explain Things to Me.

One night, Hulme and Tuny camped out on an open prairie where two cowboys drove up and teased them about the tiny pistol they’d brought to protect themselves against varmints and assailants. One of the cowboys pulled out a revolver “fully fourteen inches long” just to mock them. The men finally left. “We climbed into our sleeping bags early and lay listening to all the twilight noises of the prairie,” Hulme remembered. “The stars were suspended. I had never realized there were so many. They seemed frighteningly close overhead.” Coyotes howled. “Would they ever come near us?” Tuny asked from her sleeping bag. “Never … they are cowards!’ the author reassured her. She was talking about varmints. She might as well have been talking about cowboys. Hulme undercut that first scary encounter by mentioning that the cowboys drove up, while they were sleeping, and left them “a jar of cream and six eggs,” but the message is clear: in spite of that final gift of food, those cowboys went out of their way to let the women know they were encroaching on the territory of men.

Hulme’s book contains moments of fear, sexual peril (and titillation), and camaraderie that reminded me time and again of Wild. What puzzles me is the fact that Hulme, who went on to become a best-selling author in 1956 with her novel The Nun’s Story, either could not succeed in having the camping memoir published or didn’t even try. It was privately printed. Looking back from a twenty-first-century perspective, and with our libraries crammed with excellent outdoor memoirs written by women (Sara Wheeler, Terry Tempest Williams, Kira Salak, among many others), I find her reticence (or bad luck) unfortunate. Her book has a mischievous, revelatory quality that Hulme might have suppressed had she known the book would be available to the public. Or perhaps that provocative aspect stopped it from being published in the first place.

* * *

Aside from invading the territory of men, a few brave women authors even tried to muscle in on the male-dominated woodcraft tradition. When Kathrene G. Pinkerton published Woodcraft for Women in 1924, she was hoping to teach women the art of thriving in the forest. While some of the book has a compromised quality, with advice about bolstering male spirits with a bracing pot of tea, the book challenged women to experience the same joy and release that their husbands took for granted in camp.

“When a passion for hunting and uninhabited regions led Daniel Boone from his Yadkin farm to his adventurous life as hunter and trapper, he did not take his wife with him,” she noted. “Somehow, out of neglect, arose the impression that woods joys were for men alone. Gradually a few women discovered that the lazy drifting down a pine and rock-bound stream calms feminine as well as masculine nerves.” Pinkerton aimed to correct the problem of “isolated” female camping enthusiasts being forced to camp out as “passive observers” while the men had all the fun, and to stop men from squashing the spirit of joyful exploration in women. In a crafty and careful way, Pinkerton dared the women of America to follow their adventurous impulses by learning “the joy of maps,” overcoming the terror of being lost, and using the woods as an “enchanted playground.”

Another grand instigator was Grace Gallatin Seton-Thompson (1872–1959), wife of woodcraft genius Ernest Thompson Seton. She was every bit as wilderness-loving as her husband. Even more important, she drew links between women in the wilderness and their self-worth. Her self-effacingly titled A Woman Tenderfoot in the Rockies, published in 1900, was disguised as a memoir, but it is nothing less than a call for female independence in the wild. Seton-Thompson wanted women to know “the charm of the glorious freedom, the quick rushing blood, the bounding motion, the joy of the living and of the doing.”

She chastised any woman who would miss out on a deluxe camping holiday on horseback because of vanity: “Is it really so that most women say no to camp life because they are afraid of being uncomfortable and looking unbeautiful? There is no reason why a woman should make a freak of herself even if she is going to rough it; as a matter of fact I do not rough it, I go for enjoyment and leave out all possible discomforts.”

Seton-Thompson promised nothing less than a grand transformation of any woman who ventured into the forest. “Now this is the end,” she writes, marveling at her own change from a coddled socialite to a survivalist. “It is three years since I first became a woman-who-goes-hunting-with-her-husband. I have lived on jerked deer and alkali water … nesting among vast pines where none but the four-footed had been before. I have been sung asleep a hundred times by the coyote’s evening lullaby. I have driven a four-in-hand over corduroy roads and ridden horseback over the pathless vast wilds of the continent’s backbone.” Aside from preaching camping, she told women exactly what to bring, from eiderdown sleeping bags to enamel casserole dishes, and how to “keep your nerve” if they get lost.

Seton-Thompson’s marriage to her famous husband ended badly, with cross-accusations of cheating, and Ernest Seton taking up with his much-younger secretary. The two split up for good in 1935.

But Seton-Thompson stayed active in the women’s rights movement all her life, and she was unstinting in her support for women’s suffrage. “Wealth allowed her to choose her own way,” wrote the author Dorcas Miller in a remembrance of Seton-Thompson. “She was not financially dependent on her husband; to the contrary, in the early years of their marriage, he was dependent on her.”

* * *

Women have gone from a barely noticeable presence in camping to comprising nearly half the campers out in the forests today, according to the latest statistics from the Outdoor Foundation, the nonprofit group that represents the outdoor gear industry. Savvy outdoor gear companies are marketing brands exclusively to women. All-women campouts, from Yosemite to Alaska, have become a burgeoning presence. Meanwhile, CampOut, a members-only private camp reserved exclusively for women, has gained a following in Henrico, Virginia. The all-women proviso is so strictly enforced that the website contains an advisory warning that “There may be men on the land to clean the porta-potties. This usually is in the mornings.”

Perhaps these are signs that Victorian mores and standards have been upended. It’s also possible that these trips are a form of rebellion against gender-based modes of interpreting wilderness. Women may be reacting to a state of affairs described by experiential educator Karen Warren, who claims, “Social conditioning inundates a woman with the insistent message that the woods is no place for her.”

Those messages are hard to resist even now. Nancy C. Unger, the feminist scholar whose research inspired this chapter, admitted to me that she sometimes falls back, almost unthinkingly, on traditional roles when camping out, and recalls vividly how much her mom hated camping with her family because she ended up doing all the same chores she did at home, but in a wilderness setting, while the rest of the family tramped off to the waterfall.

If those attitudes are still with us today, then so is the spirit of these long-gone wild Victorian ladies. In spite of all the discouragement and double standards, and without the promise of an audience or the assurance that their words would make their way in the world, these women still took it upon themselves to climb mountains, hike on their own, and camp with other women.

In doing so, they claimed a piece of the wild for themselves.

* * *

All these years later, women have a large presence in America’s forests. Yet, in other ways, the American wild—and, in particular, our national parks—still put up invisible barriers for certain user groups who don’t always feel welcome there, or who have come to believe that these places are not safe or inviting for them.

One winter, I set out to talk to a group of adventurous youth, and some hardworking outdoor activists who are doing their utmost to change the woefully lopsided demographics of recreational camping.