Reading Terry Wieland on guns is like sitting in on a lecture by a popular college professor: After the first few words, you soon begin to share his fascination with the subject and appreciate the way he conveys his enthusiasm. It may be a subject that you at first felt would be of little interest (Ross rifles, for example) but soon find yourself completely absorbed and delighted with what you have discovered. Ross himself is revealed as ambitious, but the possessor of an unlovable personality. And the man with a name and career straight out of a Charles Dickens novel, Arthur Savage, maker of one of the author’s favorite rifles, we also discover to be a Barnumesque promoter of the cartridge that cracked the 3,000 feet per second barrier. And on custom guns, a topic obviously dear to his heart, we could just as well be hearing a great art historian compare and contrast Turner with Whistler.

I came to know Terry at some time, almost past remembering, when the major gun makers put on what were known as “New Product Seminars.” They would invite a gaggle of writers to some fancy place that offered comfortable hunting and shooting venues, and there we were able to do hands-on testing of whatever new wares the company would be introducing for the coming season. Some such seminars are most memorable as Falstaffian revelries, but some of us seriously wanted to learn what the makers and designers of sporting firearms had to offer. Which is when I became aware of Terry’s studious interest in guns and his perceptive way of reporting what he had learned. A well-earned reputation that was recognized when he became one of the very first writers to receive Leupold’s Jack Slack Shooting Sports Writer Of The Year award, which was justly considered the Nobel Prize of Gun Writing.

Terry is one of the very few left standing of the old school of professional gun writers. I can think of no greater accolade to offer, and can say it with authority because of my own half-century involvement in the gun-writing trade, including nearly forty years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life. I came to know nearly all the men whose stories had enchanted me when a boy. Askins Sr., Brown, Keith, Nonte, O’Connor, Page, and Whelen were giants that strode the plains of my boyhood imaginings. In time, I even hunted with some. Guns or hunting, they knew what they were talking about and had the experience to back it up. It was wise to listen to them and not argue. All gone now, bequeathing a legacy of unforgettable bylines. Then, into the decades of the ’70s and ’80s, came Wieland and other newcomers like me, searching for space in the exalted firmament to pitch our tents: Boddington, Brister, Gresham, Petzal, plus a small fistful of similar souls. Each had new stories and fresh ways of telling them and perhaps a special talent or know-how setting us apart from our fellows. A few of us had the good fortune to be encouraged (abetted) by editors like John Amber (Gun Digest), George Martin (Petersen’s Hunting), and Dave Wolfe (Handloader, Rifle,) who could tell by reading half of the first paragraph if the writer had anything to say that would interest their readers.

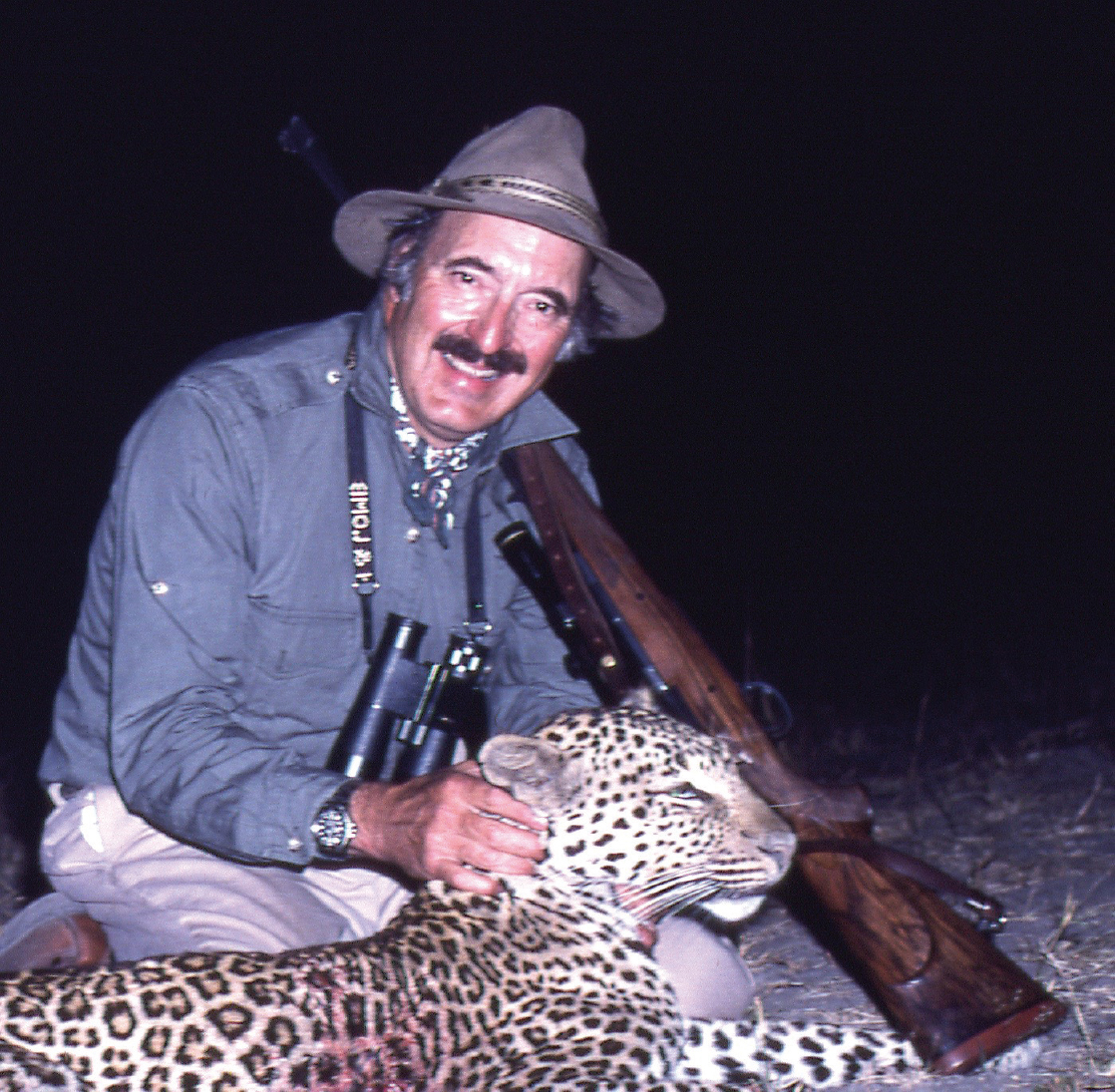

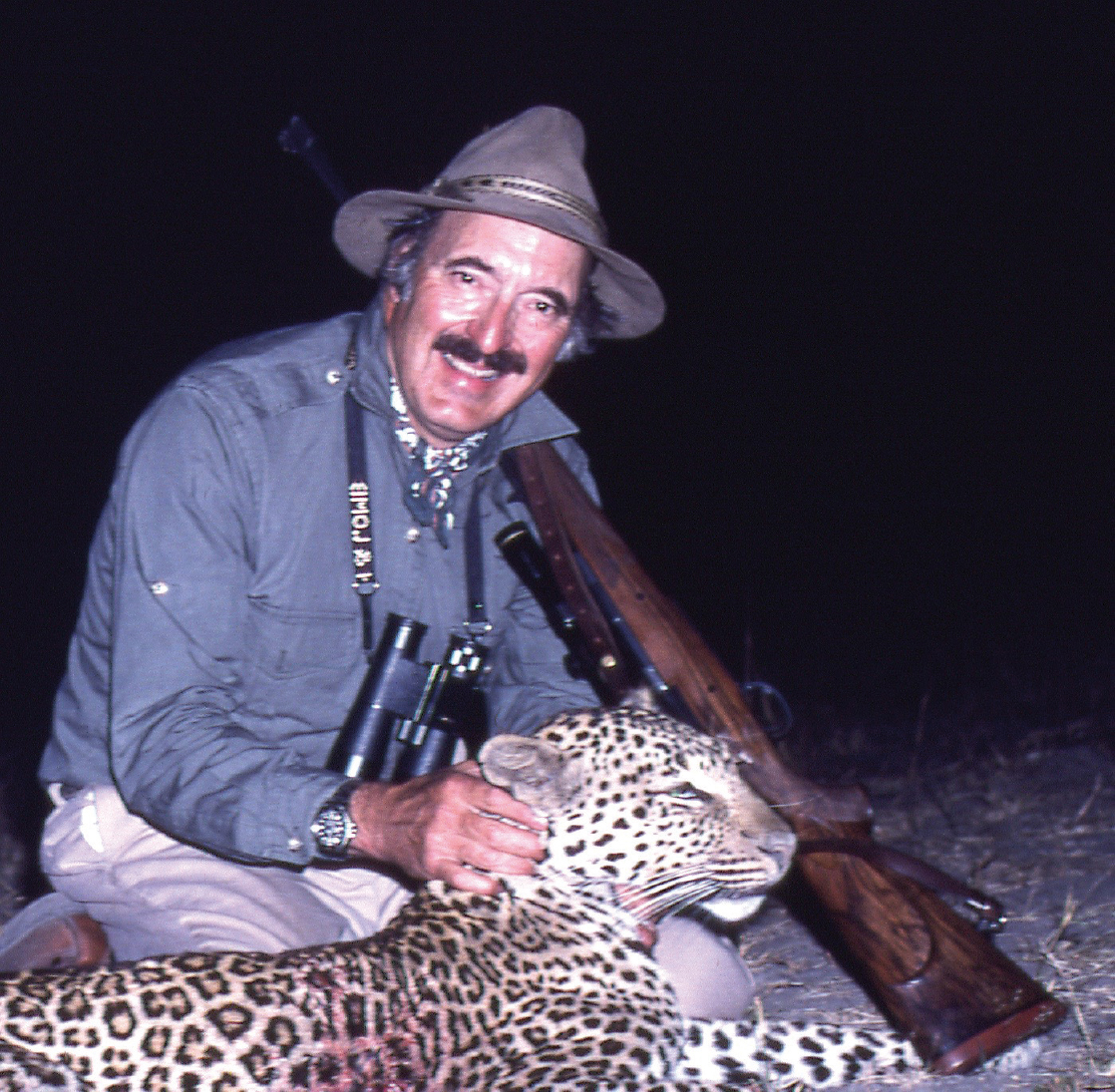

Those were pretty lush times for gun writers, especially those of us who had regular salaries from magazines like the “Big Three,” plus expense accounts that let us more or less hunt whatever, wherever, and (usually) whenever we wanted. We were further enabled by makers of guns, ammo, and everything that went with them, who were invariably eager to supply whatever equipment we deemed essential to the success of our expeditions, home or abroad. Great hunting opportunities were available in those heady times, and worldwide transportation was affordable. Most of us drank deeply from those ever-flowing wells and picked the sweetest of the low-hanging fruit. With such abundances of experience to provide foundations to our opinions, and spice to our writings, we became like those legends of generations past who trod similar trails before us.

The reason those easy times are important to describe is because, in the context of today’s shooting and hunting environment, such opportunities scarcely exist—except perhaps for the privileged few who wing the oceans in their private jets. And the makers of guns, who once prided themselves on making a better gun than their competitors, have largely been gobbled up by vast consortia that take comfort only from an ability to make a gun cheaper than their competitors. The bottom line of which is that so few of us are left from the Old School, who, like Terry Wieland, were there when great guns were being made to write about, and great hunting adventures to tell.

There is a whiff of sadness when coming to the last chapter, not just because you wish there were more chapters, but with the realization that writers of such story-telling talent and know-how to back it up are a vanishing breed. Theirs was a golden era, the belle époque of gun writing, but it spanned barely a century and Terry Wieland is one of the remaining few.

Jim Carmichel

November 2017