HOLLAND’S .500

THE 1883 “FIELD” RIFLE TRIALS

A. J. Liebling, the great boxing writer for the New Yorker through the 1940s and ’50s, noted that one could trace a continuum through boxing history based on who had punched whom, with one man punching another, who in turn hit another, all the way from Rocky Marciano back to Tom Cribb. Boxing is as inseparable from its history, he wrote, “as a man’s arm from his shoulder.”

The same is true of gunmaking, with Charles Lancaster learning from Joseph Manton, and passing it on to his sons, who taught this barrelmaker or that one, right up to the modern day. Another example would be hunting writers.

Captain William Cornwallis Harris was an English army officer. In the 1830s, on medical leave from his posting in India, he traveled through the terra incognita of southern Africa, and returned to write a book called The Wild Sports of Southern Africa. The English of the Victorian era were great readers, great seekers after knowledge, and insatiable when it came to books about far-off lands. Captain Harris’s work was a great success, and is today regarded as the first real “hunting” book as we now know them. Beyond enriching the lives of Englishmen, huddled by a coal fire on a rainy winter’s night, Wild Sports inspired others to emulate Capt. Harris, to travel thousands of miles and embark on major expeditions in search of elephants, rhinoceros, lions, and all the other great game animals of Darkest Africa.

From the great Victorian era of hunting, exploration, writing, and, not least, rifle development.

At that time, for an Englishman, big-game hunting consisted of deer stalking in Scotland and little else. Images of elephants and tigers, rhinoceros and lions, were magical. Among those inspired were such great men as Sir Samuel Baker and Frederick Courteney Selous. Both were not only hunters but writers. Baker inspired Selous, who inspired Roosevelt, who inspired Ernest Hemingway, who inspired Robert Ruark, who inspired (among others) me. Were it not for Robert Ruark (and, by extension, Harris, Baker, and Selous), I might never have taken an intense interest in rifles and hunting, and I would not be writing this book.

Of course, things are never that directly linear, and simple cause-and-effect is rarely simple. Other names are equally important. One whose contribution should never be overlooked or underestimated is Dr. J. H. (John Henry) Walsh, a.k.a. “Stonehenge,” long-time editor of The Field, author of The Modern Sportsman’s Gun & Rifle (1882 & 1884), and originator of the long series of Field trials that began in 1858 and ended in 1883. J. H. Walsh was instrumental in turning Holland & Holland from just another London gunmaker into one of the most famous and respected names in riflemaking—a reputation that endures to this day.

* * *

When J. H. Walsh took over the fledgling magazine, The Field, in 1857, the London firm of H. Holland had been in business only twenty years. Founded by Harris John Holland, a tobacconist, in 1837, Holland’s began around the time that Joseph Manton died, and is one of the few top-tier London gunmakers that cannot trace some sort of direct connection back to the Manton brothers. Holland began by buying and selling guns and rifles to his tobacco customers, and slowly moved into making and selling new guns. These early guns were brought in from Birmingham, a common practice; later, Holland’s forged a relationship with W&C Scott, one of the finest Birmingham gunmakers, and together they built a reputation for excellent quality.

In 1860, Holland’s fourteen-year-old nephew, Henry, joined the firm as an apprentice, and eventually became the driving force that transformed Holland & Holland (as it became in 1876) into a riflemaking powerhouse. It was Henry Holland’s close friendship with Sir Samuel Baker that gave H&H its connection to the real world of hunting large and dangerous game in far-off countries, and Baker had a great influence on Holland’s rifles and cartridges right up until his death in 1893.

Meanwhile, over at The Field, J. H. Walsh was making his presence felt in such a wide range of outdoor activities that it’s hard to know where to begin. The Field was founded in 1853, the brain-child of Robert Smith Surtees, creator of the famous fictional character Jorrocks, and was intended as a weekly devoted to country life and outdoor sports. Its mainstays were fox hunting and farming, but subject matter ranged as far afield as angling, greyhound racing, croquet, and, of course, shooting. Walsh, born in 1810, trained as a medical doctor, but an early mishap with a muzzleloader cost him the thumb and one finger of his left hand, and he eventually gave up medicine to become a full-time writer.

Holland & Holland was founded by Harris Holland in 1835. It is now located on Bruton Street in London, just off Berkeley Square.

J. H. Walsh was a true “all-rounder,” to use the English term. He rode to hounds, kept and raced greyhounds which he trained himself, trained hawks, trained his own pointers and setters, and coached rowing crews. He put his medical knowledge to use in developing physical fitness programs for his rowers, and the latter resulted in a book, Athletic and Manly Exercises. Another book was his Manual of Domestic Economy, dealing with making ends meet for families of all incomes; he wrote authoritative tomes on dogs and horses, and a complete compendium called British Rural Sports, which endured through many editions. Somehow, Walsh found time to design “The Gun of the Future,” (Patent #5106, 1878), a hammerless design of almost astonishing ugliness that went nowhere, and did so purely on merit. Although Thomas Bland manufactured a few of them (and we may speculate on his motives for doing so), it was one of Walsh’s few failures in life.

Dr. Walsh was a great one for full and comprehensive testing of everything. His own experience with that faulty muzzleloader made him almost obsessive about safety. Perhaps, given the contribution he later made to guns and shooting as a result, we should feel grateful to the unknown gunmaker who cobbled the treacherous gun together.

Dr. Walsh seemed to be fascinated by everything, and went to great pains to educate himself on anything in which he became interested. He was forty-seven years old when he took over editorship of The Field, and occupied that position until his death in 1888—still at his desk until the day he died. As we have seen, the modern era of gunmaking in England was in its infancy in the 1850s, and Walsh became involved almost immediately. As a scientist, he was a great believer in organized testing and evaluation. In an age when the most outlandish claims could be made for any new invention or discovery—and usually were—he became devoted to the principle of proving (or disproving) claims in full public view, and publicizing the results in the pages of The Field.

Dr. Walsh had been in the editor’s chair barely a year when he set up the first Field test, in 1858, pitting muzzleloaders against the early pinfire breechloaders. The muzzleloaders won, but it was such a close contest that it was plain the writing was on the wall. This was followed, in 1866, by trials for pattern and penetration of shotguns; in 1875, trials of choke bores versus cylinder tubes; the 1878 trials of explosives, involving black powder and the earliest smokeless powders; and, in 1879, trials that pitted large bores against small. The Field thrived on controversy, and many debates over such arcane subjects as choke boring and single triggers were fought to the bitter finish in its pages, not least in the letters to the editor. As Donald Dallas points out in The British Sporting Gun and Rifle, Dr. Walsh would allow controversial subjects to heat up to breaking point, then step in, organize an actual test, and publish the results.

In 1883, he staged what became the most famous Field test of all: the rifle trials. By this time, gunmakers were becoming known according to specialty. Some companies were noted for their shotguns (Purdey, Boss, Woodward) and others for rifles (Charles Lancaster, Alexander Henry, John Rigby). There were many areas of dispute in riflemaking, from rifling patterns (Lancaster, Henry) to bolting systems, sights, and barrel lengths. Many were the claims of riflemakers, and Walsh decided to put them to the test. On July 14, 1883, he announced a trial that would take place in just two months. Although later criticized for giving such short notice, it was intentional and served a purpose: Walsh wanted to ensure that makers could not build special rifles just for the trials, but would have to use their standard products.

According to the magazine’s official history, The Field 1853-1953, the “chief object of the trials was to determine and ascertain accuracy and trajectory of express rifles” out to 150 yards. An express rifle was any bore size from .400 to .577.

After twenty-five years of conducting such tests, the staff at The Field had amassed considerable expertise. They knew what needed to be done, but also what needed to be seen to be done in order to head off criticism from either the losing participants or members of the public. Further, Dr. Walsh was quick to see ancillary benefits that could be gained by expanding the trials in one way or the other, not just to test rifles themselves, but to compare methods of testing.

In his two-volume work, The Modern Sportsman’s Gun and Rifle, Dr. Walsh describes the rifle trials in complete detail. Volume one (shotguns) was published in 1882, and volume two (rifles) followed in 1884, the year after the trials. In retrospect, new drugs have come to market with less testing than J. H. Walsh put into the 1883 Field trial. He explains all that he hoped to accomplish with them, including comparing the accuracy of calculated trajectories based on chronograph readings and ballistic coefficients, against the actual measured trajectories using bullet holes in screens. Velocities were measured on a Boulengé chronograph, and Dr. Walsh enlisted the assistance of Major W. McClintock of the Royal Artillery, assistant superintendent of the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock, to calculate the trajectories. Major McClintock’s calculations proved remarkably accurate, and this ability to calculate trajectory was very useful to riflemakers in the future. Another contributor to the findings was J. H. Steward, described as “official optician to the National Rifle Association,” who took meteorological readings every day at precisely 11:30 a.m., Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). These readings were published with the test results, and included barometric pressure, wind direction, wind strength in relation to the north-south alignment of targets, and temperature readings from both “dry and wet bulb” thermometers.

Dr. Walsh’s most important collaborator in the tests was Frederick Toms, a gentleman seldom mentioned but whose contributions were substantial. This is not due either to neglect or a desire to give Dr. Walsh all the credit. Frederick Toms seems to have been a retiring and self-effacing individual. He is identified in Dr. Walsh’s book only as “T,” which was a common Victorian practice. He was Dr. Walsh’s assistant at The Field, and succeeded him as editor after his death. Toms then held the editor’s chair himself for ten years. The Victorians worshipped erudition and learning the way modern America worships ignorance, and Toms was a living example of this. He was born in Hertford in 1829, the son of a “malt-house clerk,” apprenticed to a printer at the age of fifteen, and when his father died three years later, found himself supporting his mother and a younger sister and brother. To educate himself, he attended night classes and joined The Field as a printer shortly after its founding. Toms became Managing Printer in 1855, then transferred from the composing room to the editorial office (highly unusual!) and assisted with the first gun trials in 1858.

Frederick Toms was what the Victorians would have described as a “philomath”—one who is a “lover of learning, particularly of mathematics and natural philosophy.” In Who’s Who, published at the turn of the century, his recreations were listed as “rural sports, mathematics, and philology.” The latter is the study of “the structure and development of language.” In 1896, he wrote a paper that was delivered before the economics section of the British Association for the Advancement of Science—quite an accomplishment for a largely self-taught man who began as a printer’s apprentice.

J. H. Walsh had, by his own admission, “little personal liking for arithmetical calculations,” and attended to the mechanical and inventive side of the trials while leaving the higher mathematics to Frederick Toms. In Dr. Walsh’s book, Toms, identified as “T,” wrote the chapter devoted to the calculations and methods used to determine trajectory. The results he arrived at were considered “authoritative” by officials at the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich, and on his death, one official stated that the world had “lost a gunnery expert whose place it would be difficult to fill.”

These, then, were the men Dr. Walsh gathered around him to conduct the 1883 Field trials of express rifles.

The trials also gave Dr. Walsh an opportunity to test the usefulness of machine rests, and he employed one made by William Jones of Birmingham (inventor of the try-gun). Another benefit, dear to the exact mind of such a one as Dr. Walsh, was that the trials defined, for the first time, the term “express rifle.” Henceforth, to qualify, a rifle would be required to have a muzzle velocity of at least 1,600 fps, and a mid-range trajectory, out to 150 yards, no greater than four and one-half inches.

By this definition, rifle sights could be regulated in such a way that the shooter could allow for differences in range, not by aiming higher, but simply by adjusting his sight picture. In books from that time, we read of hunters taking a “fine” bead, or a “full” sight. With a maximum midrange trajectory of four and a half inches, the difference could be allowed for all the way out to two hundred yards simply by taking a bead that was full, fine, or somewhere in between. Since hunters depended only on their own judgment and experience in determining range, and most were very good at it, practice with their rifles allowed them, simply by using this method, to put their bullets exactly where they wanted them within ethical shooting distances. Hence, the importance of Dr. Walsh’s definition of exactly what constituted an express rifle.

William Jones’s machine rest was not used for any of the accuracy tests. These were carried out by individuals—either the riflemaker or a designated shooter—firing the rifles from a standing rest.

Although the original test was for express rifles only, this was expanded to include rook rifles, on the small side, as well as large bores at shorter ranges. There were ten classes altogether. Participants were allowed to enter two rifles per class, up to a maximum of fifteen in total. The entry fee was £2 per rifle. In an age when a skilled craftsman lived well on a weekly wage of £3, this substantial fee ensured only serious entrants.

The classes were:

1. Single-barrel rook rifles, at ranges of 50 and 75 yards.

2. .400-bore double rifles, at 50, 100, and 150 yards.

3. .450-bore double rifles, at 50, 100, and 150 yards.

4. .500-bore double rifles, at 50, 100, and 150 yards.

5. .577-bore double rifles, at 50, 100, and 150 yards.

6. 12-bore double rifles, at 50 yards.

7. 10-bore double rifles, at 50 yards.

8. 8-bore double rifles, at 50 yards.

9. 4-bore double rifles, at 50 yards.

10. 12-bore double smooth-bore, at 50 yards.

The rules were extensive, detailed, and stringent. Each entrant was to specify the amount and type of gunpowder used, but bullets could be of any metal. Cartridge-case shape and size was specified for rook rifles, but open for all others. A rook rifle (or, more properly, Rook & Rabbit) is what we would now call a small-game rifle, roughly akin to the American .25-20 or .32-20. Trigger pulls could not be less than three pounds, and ordinary (open) sights were required except for rook rifles, where aperture sights were allowed. Cartridges would be inspected before each round, targets were specified, and order of shooting was determined by a draw, carried out at the Field office several days in advance.

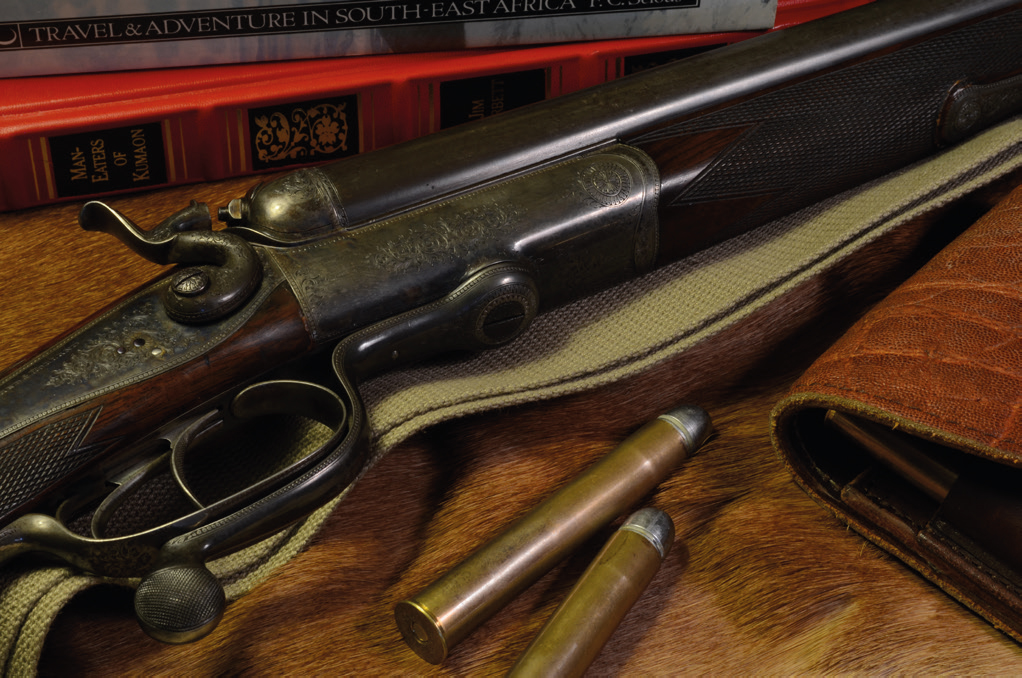

The shooting contest followed the practice of the day, and was similar to modern benchrest matches. In those days, there were two ways of measuring results. One was the “diagram.” This was what we would call a group, but it was measured differently. It was customarily ten shots, and a rectangle would be drawn through the centers of the outermost holes. All the bullet holes were then inside the rectangle, and the dimensions of the rectangle constituted the size of the diagram. An alternative method, and the one employed at the trials, was “string measure.” Five shots were fired from each barrel. The gunmaker then chose the centre-point of his group and measured the total distance to each of the ten holes from that point. The total of the ten measurements constituted “string measure.” The Field varied this slightly; instead of using the total, it used the average length of measurement.

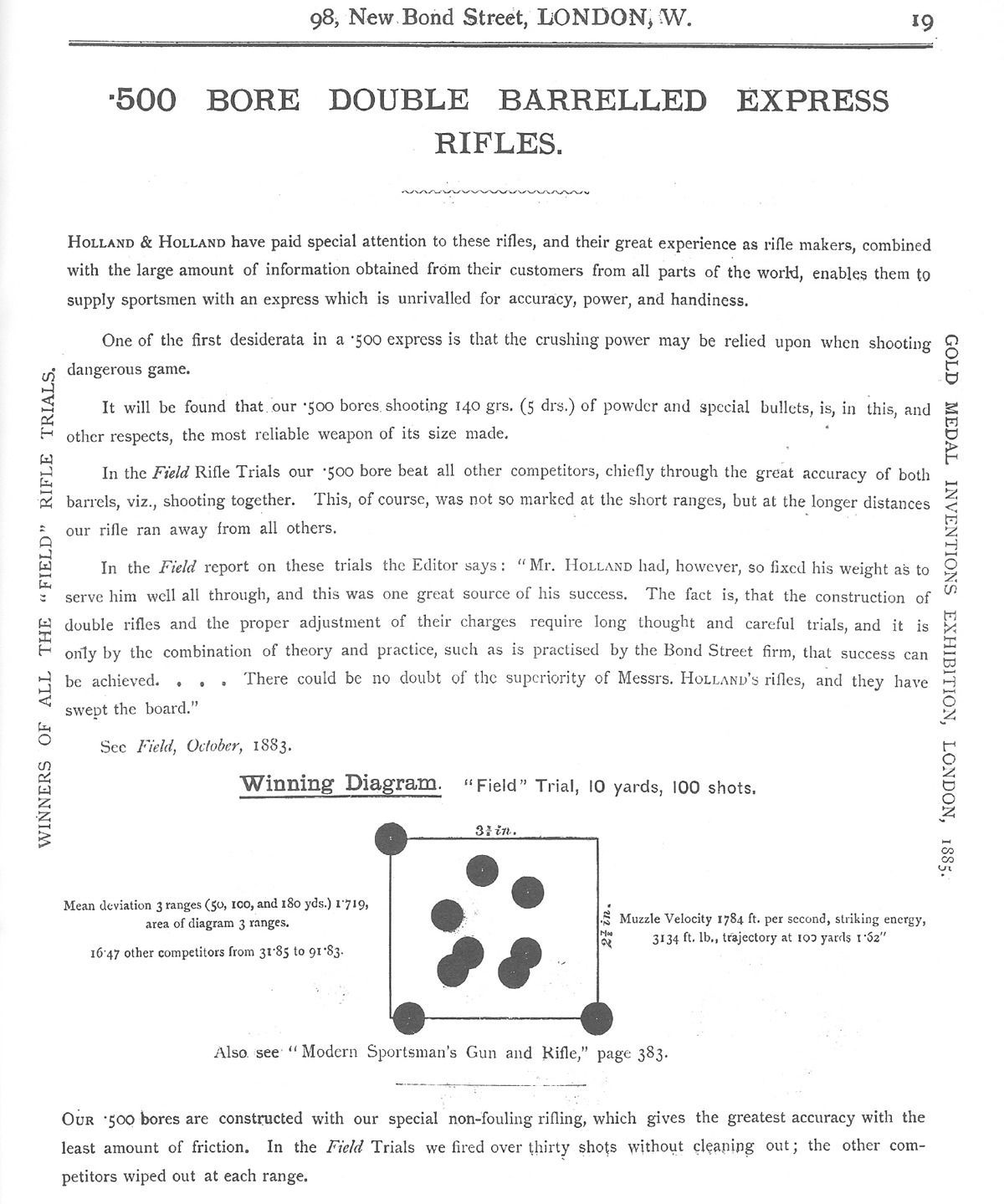

A ten-shot “diagram,” taken from the Holland & Holland catalogue of 1900, and reprinted from The Modern Sportsman’s Gun and Rifle, by Dr. J. H. Walsh.

Diagrams were shot at all three ranges, and the three string-measure averages were then averaged for a final “figure of merit.” If a gunmaker had two rifles entered, his score would be the average of the two.

Never one to miss an opportunity, Dr. Walsh also prepared diagrams for each rifle in each round, which he could then compare with string measure to see if there was any discrepancy in ranking performance. The only difference he found was that, using a diagram rather than string measure, two Thomas Bland rifles that finished fourth and fifth in the .500 class would have switched places. Dr. Walsh had thus demonstrated that the two methods were equally sound.

A criticism, leveled later, was that the overall results were not valid because many noted riflemakers did not participate. This list included George Gibbs, Alexander Henry, Charles Lancaster, and John Rigby & Co.—all big names, then and now. Although they gave various reasons, such as being too busy preparing for exhibitions in foreign countries, the real reason seems to be that Holland & Holland had already gained such a reputation in rifle circles that other makers stood to gain little from competing with them. The best they could hope for was to maintain the reputation they already had whereas, if they lost, it would be damaging.

The other participants in the rifle trials were Thomas Bland & Son, Watson Bros., and Adams & Co., all of London, and Lincoln Jeffries of Birmingham. William Tranter, the Birmingham revolver maker, was a late entrant in the rook-rifle class.

For its part, Holland & Holland embraced the challenge. It was the only company to enter all ten classes, and when the smoke had cleared, Holland’s emerged as the winner in every class. In only one category were they threatened: In the .500 double express rifle class, Lincoln Jeffries won at 50 and 100 yards, but finished third at 150, while Adams won at 150 yards. H&H finished second at all three distances. When the averages were taken, however, H&H was first, Jeffries second, and Adams third.

Holland & Holland’s string-measure average for their .500 Express—thirty shots in total at 50, 100, and 150 yards—was 1.719 inches. That is truly spectacular, but Lincoln Jeffries’s score was almost as good, at 2.060 inches. There are few hunting rifles today, with modern powder and bullets, that could do as well. While Holland & Holland, as a company, received the accolades for the victory, much of the credit for this extraordinary performance must go to William Froome. If, as stated, Henry Holland designed all the rifles that were entered in the competition, and oversaw their regulation, it is also true that the actual regulating was done by William Froome, who also shot every H&H rifle in the competition. Given the power and recoil of some of these rifles, that alone is testimony to his skill and endurance. Froome fired 190 shots in total, with the reputation of his company riding on each one.

William Gilbert Froome played a critical role in the development of Holland & Holland as a riflemaking company, every bit as important as Henry Holland himself, or Sir Samuel Baker. He eventually became a partner and director of the firm, after the death of Harris Holland in 1896. Donald Dallas states that Froome was responsible for “creating the reputation of Holland & Holland rifles,” a reputation that has lasted more than a century and is untarnished to this day. It’s difficult to argue with that assessment. If Henry Holland was a man of ideas, William Froome was a man of practical application and great skill. It would be a mistake, however, to think of Henry Holland as merely a manager. He was certainly that—and a brilliant one—but he was also an ingenious and inventive gunmaker.

Donald Dallas: “Henry Holland had incredible talents combining business acumen with inventive genius. He expanded Holland & Holland in the late nineteenth century to probably the biggest gun business in London; he set up the first large, modern gun factory, specifically designed for gun manufacture; he ensured Holland guns and rifles were an essential throughout the British Empire and, by the time of his death in 1930, had amassed considerable wealth.

After winning the 1883 Field trials, and right up to the 1930s, every Holland & Holland rifle and trade label bore this inscription.

“As an inventor, he must rank as one of the most prolific gun inventors of all time. He took out his first patent in 1879 and by the time of his last patent in 1927, a total of forty-seven patents were in Henry Holland’s name.”

It was, as Dallas notes, an “incredible tally and achievement.” These inventions included the Holland “Royal” action, and the Holland ejector, single trigger, self-opening mechanism, and many innovations related to cartridges.

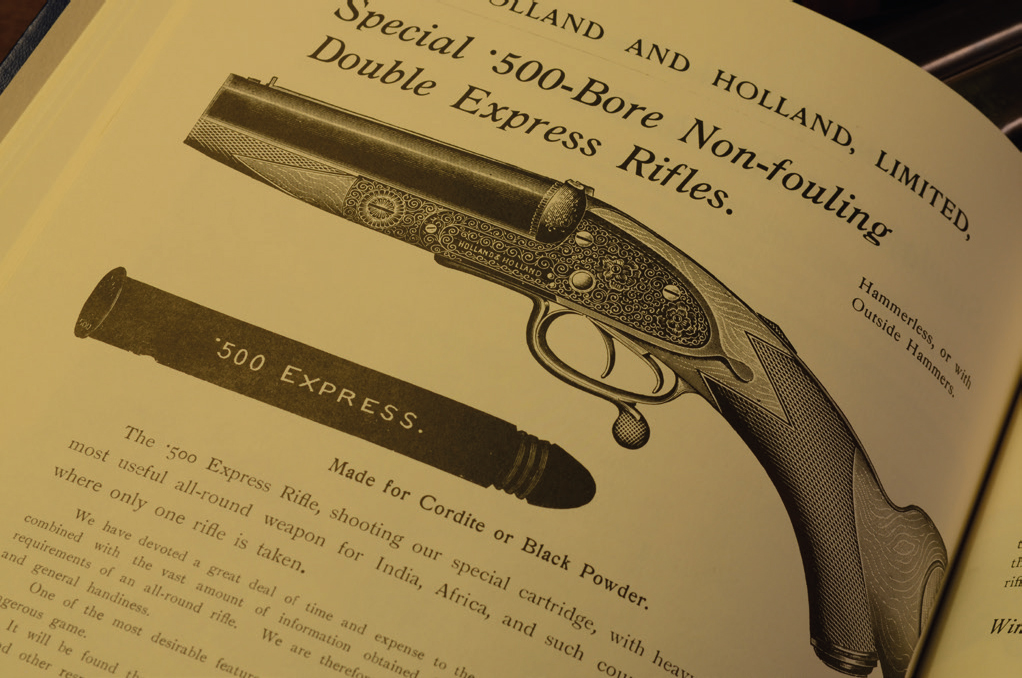

Holland’s triumph at the 1883 Field rifle trials was the beginning of the firm’s golden age. Solidly established as London’s preeminent riflemaker, Holland & Holland embarked on a series of improvements and innovations in both rifles and cartridges. A year earlier, Holland’s had introduced a rifling pattern in their rook rifles they called “semi-smooth bore.” Such small-game rifles had been a Holland specialty since the 1860s. The new rifling was reduced to the barest minimum required to grip the bullet, and consisted of narrow, shallow ridges and wide, smooth lands. This technique reduced fouling to a minimum, and since fouling was a major cause of deteriorating accuracy, it was a breakthrough. In the Field trials, the H&H rifles were fired thirty times each without cleaning, while their competitors cleaned their bores after every ten shots (as allowed by the rules.) After the rifle trials, Holland’s use of semi-smooth bore rifling was expanded to larger bores. In some rifles, at least, the bore tapered near the muzzle by five thousandths of an inch, a feature that was found to improve accuracy.

The 1880s were a time of great change: Smokeless powder was just coming into use, hammerless actions were well on their way to displacing hammers, and the shotgun world had largely settled on Purdey underlugs combined with the Scott spindle and top lever. However, the 1880s were still the heyday of double rifles chambered for black-powder express cartridges, with external hammers and Jones underlevers. This was a proven design, extremely durable, dependable, and simple.

Holland & Holland capitalized greatly on its success in the 1883 rifle trials.

After 1883, Holland & Holland settled on a couple of cartridges that became a specialty. One was the .500 Express, the rifle that snatched victory from the grasping clutches of Lincoln Jeffries at the trials. That rifle was probably chambered for the cartridge we now know as the .500 Express 3¼”, but it’s not certain. There are elements of mystery attached, and Holland & Holland itself does not have records of which cartridge it was.

By the rules of the contest, a .500 had to employ a charge of five drams (approximately 135 grains) of gunpowder, and a bullet not more than 3.5 times the weight of the powder. Therefore, the maximum bullet weight was 472 grains. This, however, does not tell us much. That was the minimum powder charge, and the maximum bullet weight. Using those parameters, the case length had to be 3¼” simply to accommodate the powder.

Although it became customary to specify, on the rifle, not only the caliber, but also the exact cartridge, powder charge, and even bullet weight for which it was regulated, the information on this H&H .500 Express double does not tell us much.

Exactly which cartridge the H&H .500 rifle was chambered for, we don’t know. Information published later stated it was loaded with 138 grains of powder, while the stated bullet weights were either 414 or 435 grain—both odd weights for that caliber. Later, H&H made published reference to their “special bullet,” but exactly what that was remains a mystery. The recorded velocity of Froome’s ammunition was 1,784 fps at the muzzle, loaded with 138 grains of powder and using either a 414- or 435-grain bullet (reports do not agree).

In the years that followed the trials, Holland & Holland developed its own .500 Express (3¼”) and maintained a proprietary hold on its exact configuration, including bullet weight, powder charge, type of powder, use of wads, and so on. As a result, when we read glowing accounts of the performance of a “Holland’s .500 Express” from the 1880s, there is some question as to exactly what it consisted of.

Regardless of that, H&H settled in to make large numbers of hammer rifles in .500 Express, with back-action locks, Jones underlevers, and rebounding hammers. Until Henry Holland built his first dedicated factory at 507 Harrow Road in 1893, these rifles were almost certainly produced in their basic form by W&C Scott, and then regulated and finished by Holland’s in London. These rifles remained extremely popular in India and Africa, among army officers and colonial administrators, well into the twentieth century. Ammunition was plentiful and it was a proven quantity. Although, in black-powder form, the .500 with its 340- or 380-grain bullet was no elephant gun, it was perfect for both lions and tigers—and tigers were the primary target of most hunters in India. Jim Corbett, who began hunting tigers around the turn of the century, started his career using a .500 express rifle. For a young Englishman heading out to the colonies in the 1890s, intending to hunt big game, a .500 hammer double was almost standard equipment.

* * *

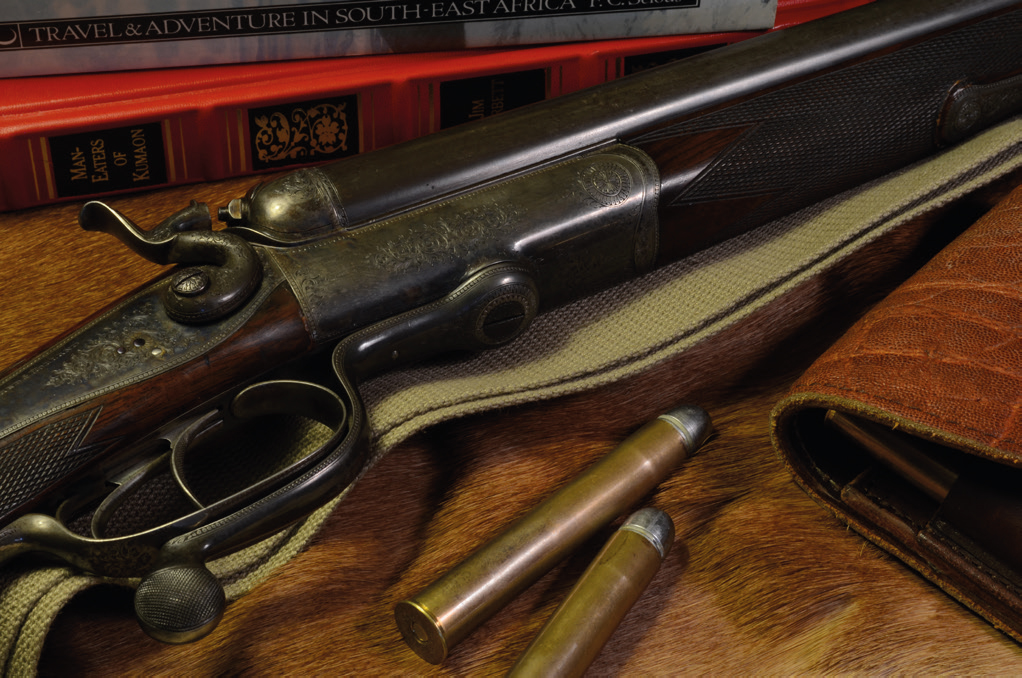

The rifle you see pictured here is a Holland & Holland from that era. According to its serial number, it was probably made in 1892, which means it likely originated with W&C Scott. Russell Wilkin, now retired as technical director of Holland & Holland, told me they had no specific record of the rifle; it was produced “for stock” and sold retail to its first owner. According to the gold stock escutcheon, this was Captain F. W. Heath, an officer in the Royal Artillery, but of course the escutcheon could have been installed by a later owner.

After 1883, and right up until the 1930s, Holland & Holland incorporated the line WINNERS OF ALL THE “FIELD” RIFLE TRIALS. LONDON not only on their trade labels, but on the barrels of rifles themselves. Because of the wide range of ammunition available from Eley Brothers, Kynoch, and other makers, it also became the custom to show the exact cartridge and powder charge for which the rifle was regulated. This was true of most British riflemakers. On my rifle, this information is engraved on the left side of the frame, and reads CHARGE 5 DRAMS. CASE 3¼ INCHES.

Fitted with rebounding locks and Jones underlever, chambered for the .500 Express (3¼”) this rifle, probably made in 1892, was produced “for stock,” not in response to a bespoke order. Note the over-the-comb tang, fitted to strengthen the wrist against the formidable recoil.

The rifle’s barrels are 26 inches long, with the usual wide flat rib, cross-filed behind the rear sight to eliminate glare. There is an express rear sight with one standing and two folding leaves. The folding leaves are marked “200” and “250,” while the standing leaf (with a wide, shallow “V” and vertical line,) is marked “50” on the left and “150” on the right, denoting the respective ranges for a “fine or full” bead. The rib is polished immediately ahead of the rear sight, but rises to a front ramp, where once again the surface is cross-filed. The front sight is a blade fixed in its slot with a pin, and has both a fine bead and a folding ivory “moon” bead.

The rifle was probably sold to Captain Heath as a retail item from the Holland & Holland shop, having been made “for stock.” Because there is no record of the rifle in the H&H numbers book, we can only speculate on where it went with Captain Heath in his career with the Royal Artillery, or what he might have hunted with it.

The rifle weighs 9 lbs. 12 oz., with a sling, and ten pounds on the nose with a cartridge in each chamber. The stock is fitted with a leather-covered recoil pad, installed many years ago, and has an elegant cheekpiece with a shadow line. There is an over-the-comb tang, and the lower tang extends the full length of the pistol grip to the grip cap. Both features strengthen the stock through the wrist. The forend is fastened with a Harvey lever. The front trigger is cross-hatched, while the rear one is smooth, and the front is articulated to protect the finger from bruising.

This is a typical example of the superb H&H big-game rifles, made for use on lions and tigers in India and the Colonies, produced in the 1880s and ’90s. Built before Holland’s opened their factory on Harrow Road, it was produced in basic form by W&C Scott and finished at the H&H shop in London.

The Jones underlever is a “partial snap” mechanism. When the action is closed, the lever comes back about two-thirds of the way, and is locked in place with the fingertips. To prevent doubling, the rebounding hammers are held at half-cock in a notch or “bent,” not merely by spring pressure.

If one set out to define the ideal lion and tiger rifle, as envisioned in the 1890s, this would be it. It is lacking none of the finer details, but nor is it burdened with any extra non-essential features. As a company that began as a retailer of rifles and shotguns, and only moved into full production for themselves in 1893, Holland’s was always conscious of keeping guns in stock for men who wanted to buy off the rack, walk out with a rifle, and catch the boat for India. As such, they had standard shotguns and rifles made up to fit their own ideas of what was suitable and what was not. In this, Henry Holland received invaluable advice from his good friend and client, Sir Samuel Baker, one of the foremost big-game hunters and rifle experts of all time.

THE .500—A SPECIALTY

The cartridge for which this rifle is chambered deserves some attention. It was not merely a generic .500 Express. Anything but! In the fifteen years between the London rifle trials and the dawn of the nitro-express (smokeless) era in 1898, Holland & Holland made a specialty of the .500 Express (3¼”), carefully tailoring ammunition to their rifles. The .500 Express (3¼”) was a cartridge that had a short life span, but was considered in its day to be the best lion-and-tiger round the world had ever seen.

The sling is a recent addition, and the leather-covered recoil pad was probably added after the rifle was made. Note the shadow-line cheekpiece.

In 1900, although the first nitro-express (smokeless) cartridges had already appeared, traditional black-powder express loads and rifles were still the order of the day, and still a mainstay of Holland & Holland’s business.

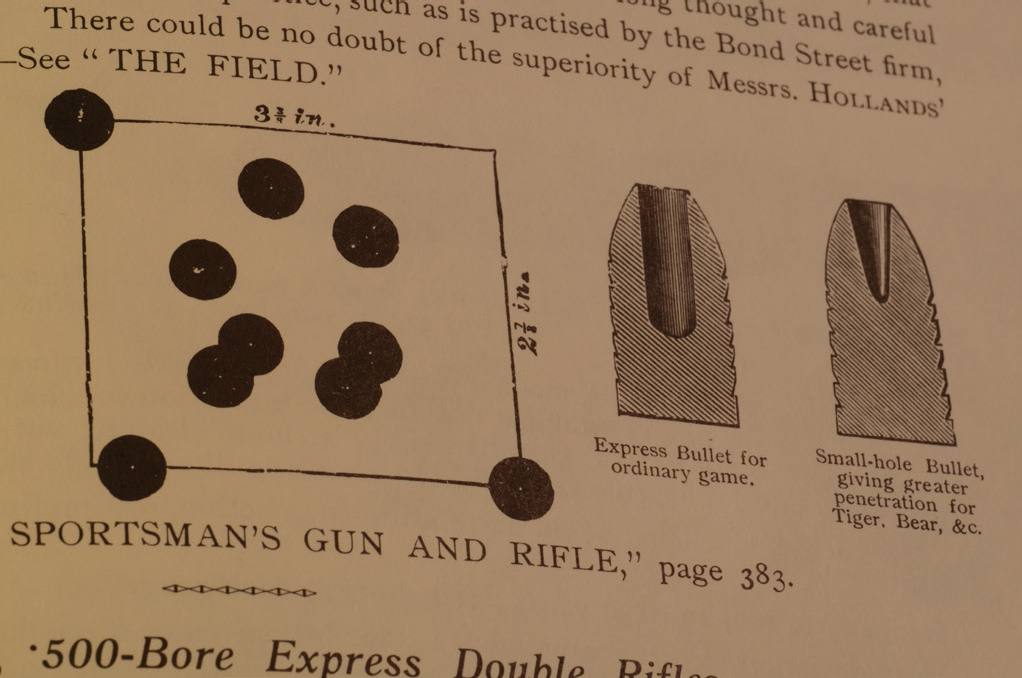

Look up the .500 Express (3¼”) in almost any cartridge book and the information will be sparse. The very first edition of Cartridges of the World (COTW) gave it barely a mention, lumping it in with the 3" version as just a variation on the theme—black-powder ancestors of the great .500 Nitro Express.

If you include both available case lengths, and then multiply by the original black powder, the later Cordite, and the in-between nitro-for-black loads, there are six variations, and they do tend to look alike from a distance of more than a century. But delve into a little history—history that is spread in bits and pieces through different books, catalogs, old magazine advertisements, and even the loading information engraved on the frame of an H&H hammer double—and the differences start to come into focus.

Although later editions of COTW expanded on the British .500s, they never did go into the particular history of the .500 Express (3¼”). As it turns out, however, that cartridge was more than just some gunmaker’s attempt to be a little different.

The 3" version was introduced sometime in the 1860s, which makes it one of the very first central-fire rifle cartridges. The round numbers are logical: A half-inch bullet in a three-inch case just makes sense. Initially, these “express” cartridges followed the pattern of the original express muzzleloaders as initiated by James Purdey, and fired a relatively light cast bullet in front of a maximum charge of black powder. In the case of the .500, standard bullet weights came to be a 340-grain hollow point and a 380-grain solid.

There were certainly other bullet weights loaded in the .500 (3"), but for stag stalking and general plains-game hunting in India, those two were the accepted standards. The cartridge belonged to no gunmaker in particular. This was before the later practice of proprietary cartridges really became established; there were several metallic-cartridge makers in Britain, and all of them loaded variations on the .500.

During this period, guns for really big game continued to be the proven 8-bores and 4-bores, with wide use of 10- and 12-bore rifles as well. By comparison, the .500 was a “medium” at best. But by the 1870s, hunters and gunmakers alike were starting to see the possibilities of smaller rifles on the larger game. Sir Samuel Baker was an unquestioned admirer of the ultra-large guns, but he championed the development of a .577 rifle even for elephants.

The three main variations of the .500 Express, from left: .500 Express, by Kynoch; .500 Express (3¼”), and the .500 Nitro Express, which was a descendant of the shorter black-powder round.

The .500 Express (3") as it existed had potential, but it also had limitations. The standard bullet was paper patched. You could increase the weight to make it more effective on bigger game, but that would reduce powder capacity; if you packed in more powder, it meant you had to reduce bullet weight. Someone hit on the idea of extending the case length by a quarter of an inch, which allowed a 100-grain increase in bullet weight while still managing to afford a little more capacity for powder.

By the way, the configuration of the 340- and 380-grain bullets is identical; the weight difference comes from hollowing out the cavity, so seating depth, overall cartridge length, and so on, are the same for both.

The longer .500 Express (3¼") would accept 440- and 480-grain bullets, and even with these, powder capacity increased to 142 grains from 136. The new cartridge was the ideal rifle for lions and tigers.

* * *

Over the years, I have had the privilege of shooting many different double rifles by many different makers, old and new, English and otherwise. Probably two dozen of them were made by Holland & Holland, ranging in size from .375 H&H up to the largest, a 4-bore double that was being built in 2009 for an American client. In between, there were a .700 H&H, a .577 NE, a .500 NE, and a .500/.465. Then, of course, there is my own black-powder .500 Express (3¼"). All of these rifles were of excellent quality and superb workmanship, but like all rifles, each had its own personality. Partly this was dictated by the dimensions, weight, and balance. The 4-bore double weighed in the neighborhood of twenty-four pounds, which is a lot of avoirdupois to hoist to one’s shoulder, hold there while it steadies, and then take careful aim. The same is true, albeit to a lesser extent, of the .700 H&H, which was a couple of pounds lighter.

Of the nitro-express rifles, my favorite to shoot was the .500 NE. It was under construction in 1993, at the same time as the .500/.465, but the dimensions of the two were quite different. The .500, while more powerful, belted me around considerably less than did the .500/.465. It just felt natural in my hand, and friendly even in its recoil. By some freak of fate, my .500 Express (3¼") hammer rifle fits me much like the .500 NE did in 1993, and in its handling and balance, it feels lighter than it is. In both rifles and shotguns, that is a key element: When a gun feels lighter than it weighs, then it is well balanced. It mounts like a shotgun, and comes to my shoulder with the sights already aligned with my eye.

On the basis of those experiences, I believe the .500 Express hammer doubles that H&H produced toward the end of the black-powder era were the prototypes for the superb H&H nitro-express doubles to come. Unlike many black-powder rifles, which differ considerably from what followed, it was as if Holland’s had perfected their lines and balance, and learned how to weave all the differing factors, and weld all the disparate parts, into a finely tuned mechanism that could perform like a Stradivarius. Having mastered the secrets of weight and balance, when black powder gave way to smokeless and the heavy nitro-express cartridges, it remained only to give those powerful rifles the same eumatic qualities (see chapter XII) as their black-powder predecessors.

The later, great nitro-express cartridges, from left: .450 NE (3¼”), .500 NE (3”), .577 Nitro Express, and .600 Nitro Express. Holland & Holland built double rifles for all of them, and these are highly prized (and expensive) today. Much of Holland’s expertise was based in their experience with the .500 Express (3¼”) hammer rifles that traveled to every corner of the British Empire.

Dedicated users of .500 Express doubles, such as Jim Corbett in India, only gave up the big .500s when something lighter yet more powerful came along. In Corbett’s case, it was a .450/.400 NE double, augmented by a .275 Rigby, as the rifle that he carried, henceforth, more than any other. The coming of smokeless powder changed everything in the realm of big-game rifles, but it does not in any way diminish the excellence of that which went before. The Holland & Holland .500 Express (3¼") is one of the great hunting rifles of all time.

Such a magnificent rifle!

The Commission ’88 bolt-action rifle.