WHAT PRICE GLORY? SIR CHARLES ROSS AND THE FABULOUS .280

AUTHOR’S NOTE AND GENERAL DISCLAIMER

This chapter was, by far, the most difficult to write in this entire book. Partly, this is because of all the disparate strands involved, including the life and career of Sir Charles Ross, the design and evolution of his rifles, and the development of his major cartridge. There is the performance of his military rifles compared to his target and hunting rifles. Finally, there is no happy ending, either for Ross or for his inventions. It all ended in a welter of confusion, with lawsuits, claims, counter-claims, hysterical magazine articles, unproven accusations that became articles of faith, and bizarre allegations about the faults of the Ross rifle that continue to this day.

Insofar as possible, we will try to deal with each of the major issues separately, but they are so intertwined that this is almost impossible. If repetition occurs in the recounting, I apologize in advance. Although this is a book about hunting rifles and their development, events that affected Sir Charles Ross’s military rifles and their reputation had a direct impact on his hunting rifles as well. The general perception of failure of the military rifles caused the closing of his factory, and that ended production of what I consider to be one of the finest hunting rifles ever made, for its time and within certain limits.

The major obstacle was sorting out fact from fiction amid conflicting claims and accusations dating back more than a century. This was aggravated by the fact that accusations on both sides (pro and con the Ross) came from writers for whom I have great respect. The most anti-Ross writer was Philip B. Sharpe, who became almost hysterical in his condemnation of rifle and cartridge, and Jack O’Connor, who was more measured; on the positive side were Frederick Courteney Selous, Major Sir Gerald Burrard, Bt., DSO, Capt. E. C. Crossman and, to a lesser extent, Col. Townsend Whelen. No less a personage than His Imperial Majesty, King George V, endorsed the .280 Ross cartridge (if not the rifle) after extensive use during his 1911 grand tour of India. The King used a Lancaster double in that caliber, similar to that used by Burrard. Ross’s major biographers, Roger Phillips, François Dupuis, and John Chadwick, attempted to sort it all out, but even their exhaustive 1984 treatise on Ross and his rifles (The Ross Rifle Story) left questions hanging in the air.

It should be noted that, in logic, it is impossible to prove a negative, and this is a severe impediment to anyone who sets out to discredit the many claims of accidents, maimings, and even deaths resulting from Ross malfunctions. For example, one celebrated incident was the supposed death of one Louis LaVallee (spellings vary) in Keith, Alberta, in 1926. He was allegedly mortally injured when he took a shot at a coyote from an upstairs window, shooting from his left shoulder, and the bolt blew back into his head. He died five hours later, so the story goes. Phillips et al report that an account of the incident was published in the Calgary Herald, and the story reprinted in Outdoor Life. At least one pro-Ross (or anti-fiction) researcher wrote that his investigations had found no record of such a person living in Keith, Alberta, in 1926, and no such story carried in the Herald. Assuming this researcher is telling the truth, what does that prove? Absolutely nothing. A quick search of the Calgary Herald archives on-line revealed nothing, but does that prove it never happened? No. Do I, personally, believe it happened? No comment.

And so we begin—with the birth of Sir Charles Ross, one of the most fascinating, infuriating, swashbuckling, gifted, and tragically flawed characters in the history of riflemaking.

PRELUDE

Sir Charles Ross—his rifles, his cartridges, his life and career—constitute an historical Gordian knot. If we add the seemingly endless lawsuits, love affairs, and political machinations, we have a plot worthy of Dickens. Sir Charles can best be described as a driven man whose lofty ambitions and undoubted talents ran aground on a combination of bad luck and his own failings. The life of Sir Charles Ross was a Shakespearean tragedy.

Sir Charles Henry Augustus Frederick Lockhart Ross, Bt. (ninth baronet of Nova Scotia, and the Ross of Balnagowan), was a man several times larger than life whose monumental failings were easily a match for his prodigious talents. His astonishing combination of brilliance and arrogance produced an always volatile, and sometimes toxic, brew. Throughout his seventy years, controversy followed Sir Charles Ross like a faithful dog. The first recorded instance of what was to become the pattern of his life occurred when he was just six years old: To emphasize his status above his classmates in Inverness, he arrived at school with a chair from the family castle. It was taller than the school chairs and he perched himself, haughtily looking down on those around. The schoolmaster was not impressed, and ordered the chair—and young Charles—removed.

Descended from one of the oldest aristocratic families in Scotland, he was heir to the second-largest landholding in Britain and what should have been a substantial fortune. He was born in 1872 on the family estate at Balnagowan, near Inverness, and grew up in the most pampered of circumstances. His father died when he was eleven years old, removing any semblance of parental discipline, leaving him to be raised by an adoring mother who granted his every wish. His mother’s indulgence exhausted most of the family’s liquid assets, so that by the time he came into his inheritance at the age of twenty-one, he was land rich but cash poor. Sir Charles’s response was to hire a lawyer and take his mother to court, alleging that, by indulging his whims, she had squandered the family fortune. That action, perhaps more than any other, illustrates the bad side of the character of Sir Charles Ross.

The estate at Balnagowan included a vast private game preserve, and young Charles grew up in an atmosphere of rifles and shotguns, shooting red grouse and stag stalking. An early childhood photograph shows him clutching a rifle taller than he is. He killed his first stag at the age of twelve, and rifles and stag stalking became his lifelong passions. The estate had an extensive armoury, and the Balnagowan gun room, according to a 1903 inventory, included guns by James Purdey, Holland & Holland, Charles Lancaster, Alexander Henry, Mannlicher, and Mauser, among others.

Sir Charles Ross was blessed with a brilliant mind—some said genius, others insanity—and a decided talent for mechanical things. By the age of twenty-two, he had taken out two patents for inventions (his first rifle and an arc lamp) and his goal was to design the finest hunting rifle of all time. His first rifle was designed while he was at Eton College and patented in 1894. It was a straight-pull mechanism that closely resembled Ferdinand von Mannlicher’s Model 1890—so closely, in fact, that some writers of the day said it was a “direct copy.” That’s not true. There were differences, including a Winchester-style external hammer, but there is no doubt that Ross was attempting to emulate Mannlicher. Straight-pull rifles seemed, in that age, to be the design of the future. Austria-Hungary had already adopted Mannlicher’s Model 1884 and would soon switch to the even better Model 1895; Switzerland adopted the Schmidt-Rubin in 1890, and in the US, Winchester used James Paris Lee’s straight-pull action in its Lee-Navy rifle. Ross was farsighted, however, and envisioned a time when armies would be using semi- and even fully automatic rifles. By 1896, he had a semiauto design completed as well.

While rifle design may have been his main interest, he was also determined to recoup his financial fortunes. He took out loans against his landholdings and embarked on a number of business ventures around the world, one of which was a rifle factory in Hartford, Connecticut.

In 1900, there was a close relationship between the great London gunmakers and the British upper classes, so it’s no surprise that Ross was able to interest Charles Lancaster & Co., one of London’s premier gunmakers, in his rifle. He persuaded Lancaster to build rifles on his Connecticut-made actions using Lancaster’s own, renowned, oval-bored barrels, and this relationship lasted for many years. Lancaster-Ross rifles were displayed at the Paris Exhibition in 1900, and at the British Military Exhibition in London the following year. Knowing how the world worked, at least at his own level, Ross commissioned presentation rifles which were then presented to the King, the Prince of Wales (later King George V), to Field Marshall Lord Roberts and, in America, Col. D. B. Wesson.

When the Boer War broke out in 1899, Sir Charles Ross hastened to South Africa where he commanded a machine gun battery, arming his men with rifles of his own design and manufacture. As an army officer, Ross was well aware of the controversies involving the relative merits and capabilities of the Boers with their assortment of Mausers, and the British and Imperial soldiers with their Lee-Enfields and the .303 British cartridge. Since Ross armed his machine gunners with auxiliary rifles of his own design, he obviously did not think very highly of the Lee-Enfield. He came back from South Africa determined to design both a better rifle and a better cartridge.

In 1902, Ross sold the Canadian government on his rifle and undertook to set up a factory in Canada. The country needed rifles, but Lee-Enfields were in short supply in England and the War Office would not allow any to be sold to the young dominion. For the Canadian government, Ross’s proposition presented an opportunity not only to fill an urgent military need but also to gain an industry. Ross began moving machinery from Connecticut to Quebec City; many of his employees also moved north, and Ross was soon deep into production of his first military rifles.

The desire to see “Made in Canada” on their military rifles was a powerful incentive for Canadian politicians in their dealings with Sir Charles Ross.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE .280 ROSS

While the new Ross Rifle Co. factory was getting into production in Quebec—and not without many hitches along the way—Sir Charles himself was back in England, in hot pursuit of the “ultimate” long-range, high-velocity cartridge. Being an inveterate stag stalker, it was natural that it would be a hunting cartridge, but he also perceived it as a target and—most important—a military round. With money always in the back of his mind, Sir Charles Ross knew that the real profits in gunmaking lay in military contracts.

It was the new age of smokeless powder and Sir Charles believed the cartridge of the future fired a small-bore bullet at high velocity. His experience in South Africa, and his study of von Mannlicher’s work in Austria, convinced him the ideal bullet diameter was .280, with a 150-grain bullet. He wanted a muzzle velocity of 2,800 fps, and more if possible. No commercial cartridge had ever reached the magical plateau of 3,000 fps, and Sir Charles Ross set out to do just that. Recognizing the advantages of a rimless case, he began with a cartridge slightly larger than the military 7x57, and in 1906 unveiled what he called the .28/06. Some references assume this was the American military .30-06 necked down, and Ross’s .28/06 was certainly similar, but there were dimensional differences. Also, it had what we would today call a semi-rimless case, although in England then it was simply called rimless. As we have seen, Ross was extremely well connected. He was able to call on friends in high places, not only politically, but in the firearms trades. Given his impatience with detail, Ross needed specialists to help turn his ideas into reality. He hired Frederick W. Jones as a consultant to help with cartridge design, and prevailed upon Eley Brothers to produce .28/06 ammunition.

F. W. Jones was one of the world’s foremost experts on rifle ammunition. Born in 1867, he entered the gunpowder business and, at the age of thirty-one, obtained a patent for coating smokeless powders to regulate burning rate. This prompted Captain Edward Schultze (of the Schultze Gunpowder Co.) to dub him “the father of smokeless powder.” He wasn’t, of course; he came along too late for that. But his coating process opened the door to all later developments, including one that made the .280 Ross possible. During his career, Jones variously worked for the New Explosives Company, Eley Brothers, Nobel, Imperial Chemical Industries, and the British government. For his later ballistics work during the Great War, he was awarded the Order of the British Empire. Sir Charles Ross could not have found a more qualified man.

But F. W. Jones was far more than just a technician. He was also a high-level competition rifle shooter and a member of the English Elcho Shield team from 1908 until his death in 1939. The Elcho Shield is an annual team competition shot at 1,000, 1,100, and 1,200 yards. By comparison, the famous Palma match is shot at 800, 900, and 1,000 yards.

Jones’s initial testing of the .28/06 recorded a muzzle velocity of 2,735 fps with a bullet weight of 150 grains. This was good performance–certainly better than the .275 Rigby, as the 7x57 was known in England–but not good enough. Sir Charles refined the case, lengthening it and making it wider at the base. This gave it a pronounced taper, highly desirable with a straight-pull rifle, since they lack the camming power of a turn-bolt to loosen stuck cartridges. In 1907, the .280 Ross-Eley was introduced to the world. This nomenclature was retained until 1912, when other companies began making .280 ammunition. Since that time, head stamps have read either .280 Ross, or simply .280.

Kynoch produced .280 Ross ammunition until 1967.

Tested by F. W. Jones, the new cartridge delivered a velocity of 3,047 fps at the muzzle with a 140-grain bullet. It was loaded, not with Cordite, but with 58 grains of the New Explosives Company’s Neonite powder, a coated guncotton-based propellant in the form of black flakes. The bullet, for reasons unexplained, was .288 diameter rather than the .284 of the 7x57. At least one modern authority believes that, while the groove diameter was .288, Ross intended the bullet itself to be .284. At the time, some ballisticians espoused the idea of bullets of bore diameter, while others believed they should be groove diameter. Almost every factory .280 Ross bullet I have measured has been .286, which is no help.

To say the .280 Ross-Eley exploded on the scene almost understates the case. From the moment of its debut, its influence spread in every direction: From target shooting at Bisley to big-game hunting in Scotland, Africa, and India; from rifle design, to gunpowder development, to the construction of hunting bullets.

The .280 Ross loaded with the famous 160-grain hollow-point bullet.

CONQUERING BISLEY

Over the years, Sir Charles Ross has had several biographers, but none more thorough than Roger F. Phillips, a Saskatchewan historian and gun collector. Phillips’s 1984 book, The Ross Rifle Story, written in cooperation with Ross scholars François J. Dupuis and John Chadwick, is the bible on Ross, both positive and negative. Phillips was not concerned with condemning or exonerating Ross or his rifles, only with documenting the truth.

Too many Ross writers over the years have depended on contemporary newspaper reports, soldiers’ letters home, politically motivated interviews, earlier magazine articles that were based on any or all of the above, and even openly biased newspaper editorials. The universal flaws with these renderings of the Ross saga are over-simplification and accepting early reports without question. This is compounded by the fact that many reporters had no familiarity with rifle mechanisms. They did not understand what they were being told, and had no basis on which to challenge questionable statements.

At this point, we could follow the Ross story down several paths, and trying to explain the .280 Ross cartridge and its career is like picking out the hoofprints of one particular horse and following them through a stampede. You pick up the trail, you lose it, you pick it up again.

In 1907, F. W. Jones took a prototype .280 Ross-Eley target rifle to the Bisley matches, not to compete, but just to see how it performed. The Field reported that Jones made “a number of possibles,” and the Ross team went home and began building a real target rifle for the next year’s matches.

The annual Bisley meet in England includes competitions for both service and match rifles. The .280 Ross was purely a match rifle, but Ross’s service rifles, as used by the Canadian militia, were chambered in .303 British. Accordingly, Ross became involved in both types of shooting, as well as production of superb match ammunition in both .280 Ross and .303 British.

Between 1908 and 1913, Ross and his products competed in all and dominated most. Not surprisingly, there always seemed to be an element of controversy. This happens when one rifle or cartridge comes to dominate competition: Losers look for excuses and some of them even file protests. First, the .280 match rifle. According to Phillips, Ross’s special match rifle had a heavy barrel with a unique lede. Instead of a tapered throat to guide the bullet into the lands, it had parallel sides and the cartridge was a “push fit,” similar to that used by schützen competitors. The long bullet was then positioned to enter the bore precisely. The .280 Ross-Eley target ammunition was loaded with a 180-grain spitzer full-metal jacket bullet that we would now call “extra-low drag.” This was just one of many ways in which Ross and Jones were ahead of their time. The muzzle velocity was 2,700 fps—not at all bad, even today.

Ross match ammunition, in .303 British (left) and .280 Ross. Even this was controversial. Both won their share of silverware, in both Ross rifles and those of other makes. The .303 bullet weighs 200 grains, while the .280 is 180 grains.

In 1908, F. W. Jones all but swept the field, winning five individual and aggregate long-range matches. It was a phenomenal performance–at least until Britain’s National Rifle Association (NRA) received a complaint and found that, although the rifle as a whole was within legal weight, the barrel itself was a couple of ounces too heavy. Jones returned the silverware, but the Ross retained the glory. Partly due to its performance and partly to Sir Charles Ross’s abrasive manner, the rifle and cartridge made enemies. In 1909 and 1910, the Eley match ammunition was not as good as it had been. This led to conspiracy theories and prompted Sir Charles Ross to begin making his own. He added an ammunition production line at his factory in Quebec, using brass obtained from the U. S. Cartridge Co., and making such excellent match ammunition, in both .280 Ross and .303 British, that the Canadian service-rifle team dominated competition at Bisley between 1909 and 1913.

Roger Phillips: “In 1910 they won principally the Mackinnon Cup, the Daily Graphic Cup, and second place in the prestigious King’s Prize match. In 1911 they did the ultimate, winning both the coveted King’s Prize and the Prince of Wales Prize, an unprecedented achievement.”

These two prizes were both won by Private W. J. Clifford, top shooter on the Canadian team, which won a host of other honors, and defeated the British team overall with 1,581 points to 1,569.

The .303 match ammunition used in 1911 was specially prepared by the U. S. Cartridge Co. to Ross’s specifications. It fired a 174-grain hollow-point bullet, manufactured at his rifle plant in Quebec, using a machine of his own design. It had a soft iron jacket, was coated with a mixture of wax and graphite, and had a muzzle velocity of 2,638 fps. (It should be noted that Ross’s .303 match ammunition used different weight bullets at different times, ranging from 174 to 215 grains.)

After the 1911 matches, there was the usual round of carping, sour grapes, and murmured innuendo from other teams, but nothing came of it. Then, in 1912, pitted against the very best .303 match ammunition that could be made in the United Kingdom, shooters using Ross match rifles and ammunition won fifty of the ninety-four prizes. Many old records were shattered, including the 1,200-yard King’s Norton match, where Canada’s George Mortimer made a new world’s record, scoring 73 out of a possible 75.

Phillips: “During the years 1911 and 1912 Ross was truly the master of Bisley. Never before in history had one man’s name so dominated the scene there. The caliber .303 Ross Mark II** (the Canadian service rifle) was without peer among the service rifles of the Commonwealth and Ross .280 match ammunition proved beyond doubt that smaller caliber bullets driven at high speed had unsurpassed accuracy.”

This was undoubtedly the high-water mark of Sir Charles Ross’s career, not just at Bisley, but as a riflemaker. Alas, his less admirable personality traits had served to alienate too many, including his colleague, F. W. Jones. British gunmakers had begun barrelling Mausers and Mannlichers to shoot the .280 Ross, and Jones switched rifles. Competitors using Ross ammunition in non-Ross rifles were so successful that Ross ordered that his match rounds be sold only to competitors using Ross rifles. This in-fighting ended with the beginning of the Great War, and when it was over, the Ross Rifle Co. was out of business.

* * *

Although the .280 Ross was initially a target cartridge, its designer intended it also as a military and hunting round. After the 1908 Bisley triumph, gunmakers began chambering hunting rifles for it, as well as developing proprietary cartridges to compete with it. In Germany, Mauser’s new magnum action suited the .280 Ross perfectly, and it became a standard Mauser chambering. Ross’s friends at Charles Lancaster & Co. chambered the .280 Ross in their bolt rifles, and also developed a flanged (rimmed) version for use in double rifles and single-shots.

The British War Office, impressed by both the cartridge and the Ross rifle’s performance at Bisley, began development of an entirely new military rifle to replace the Lee-Enfield. This was the Enfield P-13. Its long Mauser-type action was intended to accommodate the new .276 Enfield cartridge, a round so similar to the .280 Ross that the source of inspiration is undeniable. With the outbreak of war in 1914, work on the new rifle/cartridge combination was halted, since the War Office quite rightly did not want to get into a changeover in the midst of a shooting war. The cartridge was abandoned but the rifle was not; it was subsequently adapted to the .303 British (P-14), and later the .30-06 (P-17).

The .280 Ross was as successful on big game as it was on targets. The 1914 Charles Lancaster & Co. catalogue contains fourteen pages of photographs, testimonials, and reprints of magazine articles praising the .280. Most are unsigned, since a gentleman of that time rarely wanted his name in the public prints. There was, however, one exception: Charles Lancaster had more royal warrants than any other London gunmaker, and in 1911, its most illustrious client was His Imperial Majesty, King George V. In that year, the King took his Lancaster .280s on his grand tour of India, and shot everything, including Indian rhinoceros and Bengal tigers. In a letter, he described his .280s as “a great success.”

Most of these letters were dated 1911 or 1912, and 1911 was also the year of the .280 Ross’s most notorious failure. George Grey, brother of the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, was killed by a lion in Kenya after shooting it five times with a .280 Ross. Dying in a Nairobi hospital, Grey admitted it was his own fault for riding too close to the lion. Ever since then, however, it has been held up as an example of the inadequacy of high-velocity bullets on dangerous game.

* * *

The .280 Ross long outlived both the rifle and its designer. Ammunition was manufactured until 1967, when Eley-Kynoch finally discontinued it, but during its sixty years it had enormous influence. In the United States, du Pont developed a new powder, #10, which made possible the .280 Ross’s wondrous ballistics in American-made ammunition. Introduced in 1910, but not released for canister sale until 1912, it was discontinued in 1915. According to reports, until it was released to the public it was known as “Ross powder,” and competitors obtained supplies by buying Ross ammunition and pulling the bullets. DuPont #10 made possible the high-velocity cartridges of Charles Newton, introduced around this time, and set the stage for a series of ever-slower burning powders in the IMR series.

On a less serious note, in the 1920s, the German-American ballistic fraudster, Hermann Gerlich, took the unaltered Ross case, renamed it the .280 Halger, and embarked on his comic-manic campaign to convince people he was getting unbelievable velocities.

In 1920, the irrepressible Sir Charles Ross, advised by his doctor to get a complete rest, complied by booking a long safari in East Africa with his extra-marital friend, the New York big-game-hunting socialite, Mrs. Emily Key Hoffman Daziel. The safari provided the second Lady Ross, the beautiful Kentucky heiress Patricia Ellison, with the ammunition for a lurid divorce suit. In the meantime, Sir Charles and Mrs. Daziel used the safari to demonstrate the effectiveness of the .280 Ross once and for all. On his return home, he commissioned a bust of himself, dressed in safari garb. His cartridge loops all contain the distinctively long, tapered .280 cartridge. The bust, in marble, now resides at Balnagowan.

It’s only fair to give the last word to Sir Charles Ross. In a letter written in 1919 to a former Canadian infantry officer, in which he undertakes to explain everything that took place regarding his rifles between 1912 and 1916, Sir Charles rather plaintively states that “The true Ross rifle was my ‘sporting rifle,’ which I designed myself; the military rifles turned out at my factory were an official arm over whose structure I had no control . . .”

Self-serving as this might seem, the facts, as compiled by Roger Phillips, bear it out. And the “sporting rifle,” of course, includes the .280 Ross cartridge. While his accomplishments have been almost obliterated by the “Ross rifle controversy,” the .280 Ross was certainly the first, and one of the greatest, of all the 7mm magnums.

A CAREER IN THE MILITARY

The controversy that sank the Ross rifle, the company that produced it, and the reputation of Sir Charles Ross himself, was rooted in Canadian politics as much as anything. Having sold the Canadian government on a Canadian-made rifle for its militia in 1902, Sir Charles built a factory near Quebec City, imported skilled machinists and craftsmen from the United States, and began to build his rifles.

These were all straight-pull designs, and went through several models with alterations and improvements often being implemented in mid-production. Ross did not follow the practice of the British War Office in designating models and sub-models with numbers, marks, and asterisks, punctuated by formal periods of range, field, and troop trials along the way. Confusing and ponderous as that system might seem, it is vastly superior to Ross’s “damn the torpedoes” attitude. Although Ross rifles today are denoted by numbers and marks, these were mostly determined long after the rifles themselves were manufactured and assigned retroactively in an effort to eliminate confusion.

Almost from the beginning, there were problems with Ross’s straight-pull design. The most notorious instance involved an NCO of the Royal North-West Mounted Police (later the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) who was badly injured when a rifle self-destructed, for lack of a better term. That was in 1905. Ross corrected the faults, and what emerged was the rifle now known as the Mk. II, or 1905 Ross. Like both the Mannlicher and the Mauser, the Ross had twin opposing locking lugs that rotated into recesses in the receiver ring by the camming action of the bolt sleeve. The 1905 had solid lugs, was quite a good rifle, and later saw service with some units of the American military, among others. It also has the most graceful action of any Ross, and could be the basis of an interesting custom rifle.

The Ross Model 1905 (or Mk. II), in .303 British, was dependable, accurate, and saw long service with many countries, including the USA. It has the most graceful action of any Ross rifle, and is beautifully made.

It was followed by the Mark II**. During 1909–10, Ross made substantial changes to the action, chief of which was switching from solid locking lugs to an interrupted-thread design similar to a big naval gun. Ross claimed as much as 50 percent more strength in this design, which was borne out by proof testing. Unfortunately, the rifle was not subjected to sufficient operational testing, under field conditions, before being put into production. It was made with a very tight (match quality) chamber, which later proved to be the main cause of its downfall, although there were other problems as well.

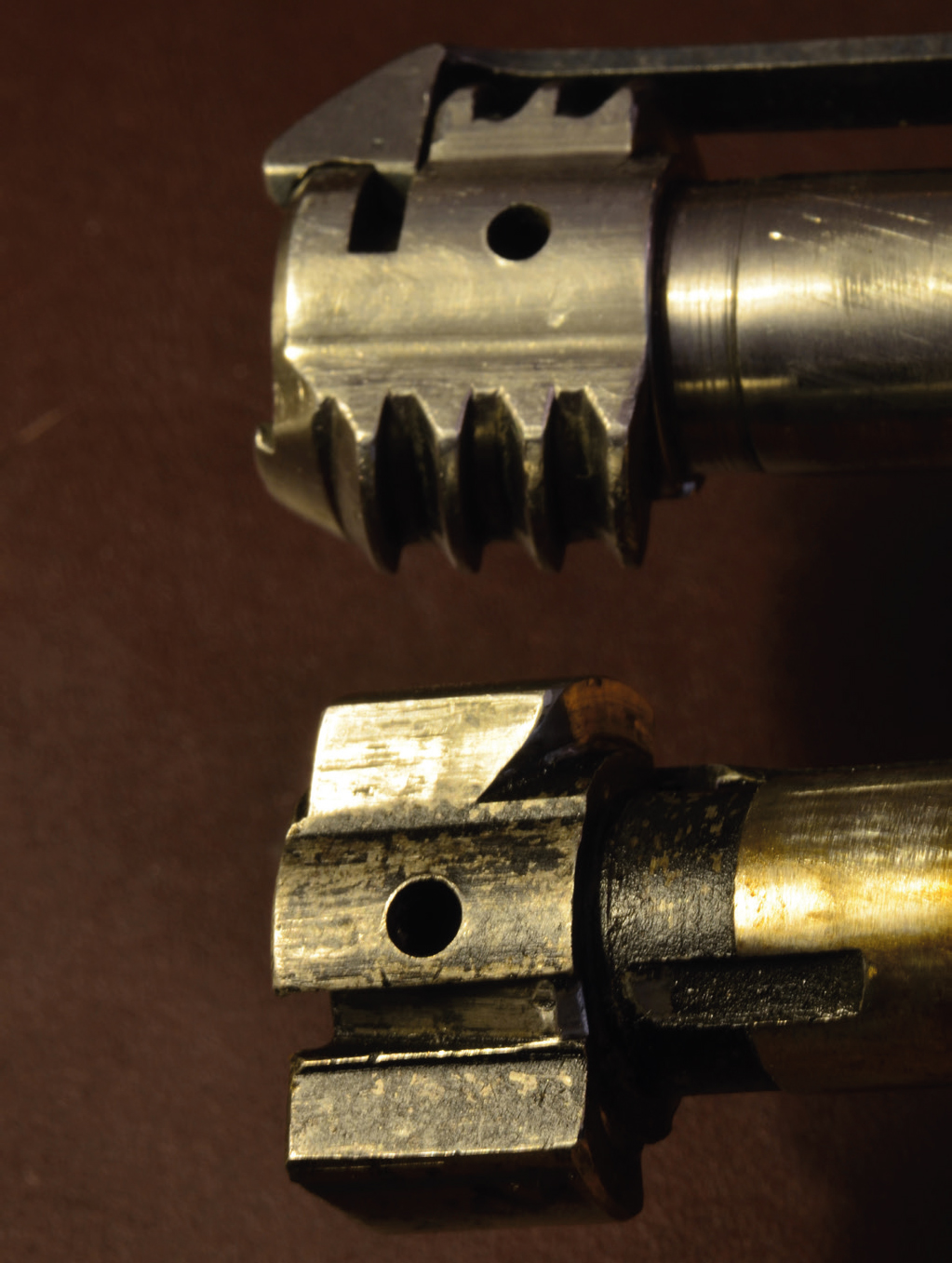

The bolt of the Mk. II** (or Mk. III) used interrupted-thread locking lugs, similar to an artillery piece or naval gun, rather than the usual dual opposing lugs of the Model 1905 (Mk. II).

The interrupted-thread locking mechanism was immensely strong, as indicated by the proof levels. According to Roger Phillips, it withstood proof pressures of 150,000 psi.

The Mark II** was also known as the Mark III, and a 1913 army manual refers to it as such. The same action was used for the Model 1910 (M-10) civilian hunting rifle. The M-10 was chambered for the new .280 Ross cartridge, which was intended as a military, target, and long-range hunting round, all in one.

The Mark II** was adopted by the Canadian militia (forerunner of the Canadian Army). The minister of militia in the federal government was Sam Hughes, a friend of Sir Charles Ross since Boer War days, and one of the least admirable characters in Canadian political history. Sam (later Sir Sam) Hughes was a tall, imposing, vain, overbearing, and blustering character who bullied everyone around him. From the beginning, his relationship with Ross, and his championing of the Ross rifles through thick and thin, gave rise to suspicions of nepotism and unethical dealings. Inevitably, the Ross rifle became linked with Sam Hughes, which made it a target for Hughes’s political enemies—of whom there were many, and whose numbers increased steadily through the years.

When war broke out in 1914, Canada immediately declared war on Germany and pledged military and logistical support for Britain. Canadian soldiers went overseas armed with Ross rifles chambered for the standard .303 British. This was the rifle Ross all but disowned in the letter quoted above, and it certainly had problems. It was more a target rifle than a rough-and-tumble military arm like the Lee-Enfield. Undoubtedly accurate, it was also very finicky as to the ammunition it would accept. As long as Canadian troops were supplied with Canadian-made ammunition, everything was fine. In the chaos of war, however, this could not be guaranteed, nor could the uniformity of ammunition from a wide variety of factories in many different countries. The Lee-Enfield could accommodate these anomalies; the Ross could not.

Canadian troops went into battle for the first time in the spring of 1915, and problems with the Ross were reported almost immediately. Mostly, these involved rifles jamming as a result of the varying ammunition, and the lack of camming power in the straight-pull action to break a stuck cartridge case free of the chamber. Another cause of jamming, which developed later, was the rear-most thread of the left locking lug striking the bolt stop. This caused peening, which resulted in the bolt sticking when it was slammed closed. The ammunition problem was resolved by recalling Ross rifles and opening up their chambers. The peening problem was solved by installing a wider bolt stop that would not hammer the thread enough to damage it. There was, however, a third problem, and this was the one that would bedevil Ross rifles, military and civilian, henceforth and to this day.

Accusations arose that it was possible to assemble the bolt incorrectly, in such a way that it would only appear to be closed, yet still fire a cartridge. Because it was not locked, it would then fly back and injure or kill the shooter. These accusations were seized on by Canada’s political opposition party, and its allies in the press, in order to attack the government. The enmity that Sam Hughes had built up during his bullying, blustering career was coming home to roost, and his underhanded behavior in support of the Ross only made it worse. Eventually, in the spring of 1916, the British Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig, ordered the Ross withdrawn from service completely, to be replaced by the Lee-Enfield. This was the rifle with which the Canadian Corps fought the rest of the war.

Although there are no recorded and confirmed instances of a Canadian soldier being killed by a bolt blown back, the accusation remains, more than a century later. Phillips et al do mention one case of a soldier allegedly being killed. It was described by a former Canadian Army armourer, Lindsay C. Elliott. In a letter to H. V. Stent, a firearms writer with Outdoor Life in 1922, Elliott wrote that a soldier standing next to him in a trench was killed when the bolt blew back, and on examining the bolt, Elliott found it had been “misassembled.” Furthermore, he stated, this was not the only instance he knew about. This is puzzling, not to say suspicious, for reasons we shall see shortly. No mention is made of that incident when, in 1938, the official history of the Canadian Army in the Great War was published. It included a separate appendix (Appendix III) dealing with the Ross rifle issue, which dealt at length with the ammunition problem as well as the peening of the locking lug. Nowhere, however, does it mention a single instance of a bolt blowing back and injuring a shooter. The official history was compiled and written with complete objectivity, twenty years after the Armistice, when the main characters were long out of public life. Its authors, and the Canadian Army itself, had no ax to grind, and no political considerations to worry about. Had the blow-back problem genuinely existed, it should certainly have been prominently mentioned. There is nothing.

However, such was the extent of the controversy, even this omission is subject to examination. Roger Phillips and his co-authors suggest that just because they are not documented in the public records does not mean they did not happen. They suggest that since most shots were taken with soldiers standing up in the trenches, bolts blown back would miss their heads and cause no injury. Well, not according to Lindsay C. Elliott, who claimed to have been standing beside the dead man in the trench when it happened. But, to continue.

In 1999, Canadian arms historian Clive Law undertook to reprint Appendix III, under the title “A Question of Confidence,” to ensure that such an important historical document remain readily available to researchers. In the foreword, a professor from Canada’s Royal Military College notes that Lt. Col. A. F. Duguid, lead author of the official history, obviously sided with the anti-Ross faction, yet he does not go out of his way to condemn the rifle for alleged blow-back incidents.

Toward the end of the war, amid a flurry of claims and counter-claims, and contracts unfulfilled, the Canadian government expropriated the Ross Rifle Co. factory in Quebec, and in 1920 paid Sir Charles Ross the then-immense sum of $2 million in compensation. He retired to Florida, where he lived out the rest of his life, a very wealthy man.

Over the next twenty years, a small growth industry sprang up within the legal community, suing Sir Charles Ross on behalf of shooters who had allegedly been injured by the infamous “deadly bolt” of Ross hunting rifles. To all appearances, rather than fight case after case, and probably just weary of it all, Sir Charles took to settling many of these out of court. He could well afford to do so, but such an approach did nothing for either his own reputation or that of his rifles. When one goes looking for actual instances of injuries, of incidents involving poorly assembled Ross bolts, they either cannot be found or are highly questionable. Undoubtedly there were genuine incidents, but equally undoubtedly, Sir Charles Ross found himself tagged by lawyers as an easy mark. In civilian circles, the Ross M-10 in .280 Ross acquired a reputation as being only slightly less dangerous than a black mamba.

Ever since, articles about Ross and his rifles tend to quote earlier articles, which in turn quote articles from earlier still. With each telling, the accounts of injuries become more serious but less specific. I saw one in which it was stated that “thousands of Canadian soldiers died” because of Ross malfunctions. This is utter hogwash. The Canadian Corps established itself as the premier fighting unit on the Western Front, of any army on either side, beginning with its very first action in April 1915. For the next four years, it never retreated without orders, never failed to take an objective it was ordered to take, and never lost a position that was not quickly retaken. An army does not compile a record like that using a worthless rifle.

In his Complete Book of Rifles and Shotguns (1961), Jack O’Connor wrote that the Ross Model 1910, with the interrupted-screw locking system, “was a bad actor if the bolt was incorrectly assembled. It was possible to fire this model unlocked, and many people were maimed and even killed when the bolt blew back into their faces.” As a professional journalist, he probably thought he was playing it safe with such a general statement. Even so, it’s surprising O’Connor would write that.

Roger Phillips et al include a chapter, “Ross Rifle Accidents and Causes,” in which they attempt to track down and evaluate specific incidents. They even go so far, when court records can be obtained, to name the lawyers and law firms who acted for the plaintiffs and the defendant, as well as damages claimed and damages paid. While including considerable detail, this chapter in some ways is as infuriating as other accounts, where the issue becomes a will-o’-the-wisp, with the real cause always flitting just out of reach. For example, there was the case of Louis LaVallee (or LaValley) mentioned earlier. Conversely, the most recent incident reported occurred in Deep River, Ontario, in 1965, and the authors not only spoke to the victim, but knew the location and current owner of the rifle in question. That is difficult to dispute.

One disturbing thread that runs through most of the accidents reported in that chapter is that they involve borrowed rifles. The victims usually (though not always) were unfamiliar with the Ross and its operation. This does not excuse anything, of course, but it does suggest that it is not a rifle you want to lend to a friend to take hunting, especially if he’s the kind of guy who will want to take everything apart to see how it works. Experienced soldiers and riflemen, who knew the rifle intimately, used them without a problem, often under the worst conditions, and admired them for their accuracy.

Philip B. Sharpe became a very vocal critic of the Ross rifles, although his attitude is somewhat contradictory. In both of his books he becomes almost hysterical in insisting that no Ross rifle with an interrupted-thread bolt should ever be fired, under any circumstances; elsewhere, he tells of buying a half-dozen Ross rifles when the US government disposed of its remaining stock, then “shooting them to pieces.” He writes that he attempted to assemble a bolt incorrectly and make it fire, but while he could do this to a point, the firing pin could not reach the primer. He was working with primed cases only (not live ammunition) but never succeeded in igniting a primer. This only adds to the mystery. During the Great War, in urgent need of small arms of all kinds, the US government purchased twenty thousand Ross Mark II rifles (Model 1905) and presumably these are what Sharpe obtained. Since the 1905 has solid lugs and was never accused of any of the faults of the Mark II**, it’s hard to see exactly what Sharpe thought he was proving.

We will return to this issue, but first, a look at the Ross M-10 hunting rifle. As a child, Sir Charles Ross stated his ambition to design “the greatest hunting rifle the world has ever known.” When the Ross M-10 (.280 Ross) sprang upon the world, he had done exactly that, at least in terms of range, accuracy, and killing power. It was also a beautifully made and finished, well-balanced rifle with a superb hunting stock. Being made in Canada, it was available to big-game hunters on both sides of the Atlantic, and it quickly got a lot of attention. In America, one of the most prominent and influential gun writers of the day was Capt. E. C. (Ned) Crossman. He was sent one to try and famously called it “the rifle of my dreams” in a 1910 article of the same name that appeared in the NRA publication Arms and the Man (forerunner of The American Rifleman.)

By the time the Ross Rifle Co.’s 1914 catalogue was released, Ross had gleaned a raft of glowing reports on his rifle. Some were tales of spectacular long-range kills; others praised the speed of the action (three black bears dead in twenty-three seconds, and that kind of thing.)

The catalogue itself, which is available in reprint from Cornell Publications, makes very valuable reading for anyone with an interest in ballistics and rifle performance. It examines in detail every aspect of the M-10 Ross sporting rifle, its cartridge, the bullets available for hunting, the proven accuracy, the function and strength of the action. No possible question is left unanswered, yet it’s all couched in very reasonable tones—neither strident nor excessive. In fact, it exudes an air of quiet confidence—certainly well-deserved in light of the rifle and cartridge’s performance at Bisley, and the reports then coming in from the big-game countries of the world. It reads very much like one of the London gunmakers’ catalogues of the era, such as Holland & Holland’s.

THE ROSS .280 M-10 SPORTING RIFLE

The M-10 sporting rifle, based on the Mark III (or Mark II**) action, is the most famous of the Ross big-game rifles, but by no means the only one. An earlier sporter, the Model E, was based on the predecessor Mark II, or Model 1905, action. That rifle had exceedingly pleasing lines, abetted by the streamlined shape of the action, and was available in either .303 British or .35 Winchester.

This was followed in 1907 by the Ross High Velocity Scotch (sic) Deer Stalking rifle, the first to employ Ross’s new interrupted-thread locking lugs. By the time the 1914 catalogue appeared, this had evolved into the M-10 sporting rifle, the flagship in the Ross line. There was also the Model R, a civilian version of the military Mark II** with the extended box magazine, chambered for the .303 British and rated at a weight of just 6 lbs.12 oz. The Model E-10 was similar, but with a more refined stock, better finish, and checkering. For the record, the M-10 listed at $55.00, the E-10 at $42.50, and the Model R for $33.00. By comparison, the Haenel-Mannlicher New Model we looked at in an earlier chapter was available at the same time for about $26.00.

Personality aside, Sir Charles Ross was the perfect person to design a hunting rifle: He was a dedicated and experienced hunter who grew up stalking stags in the Highlands, and he knew the qualities a fine hunting rifle required. His mechanical aptitude allowed him to project how a rifle should operate best, and then turn it into reality. Having grown up with Purdeys and Holland & Hollands, he recognized quality and fine workmanship, and his long association with Charles Lancaster gave him an understanding of what was meant by building London quality into a rifle of his own design.

The Ross sporting rifles were built to the highest London standards of fit and finish. Even the military Model 1905 actions are sleek, smooth, and beautifully finished. Their military stocks leave something to be desired, but then, all military stocks did. When it came to the M-10, Sir Charles Ross put all his expertise into fashioning a rifle that was far ahead of its time in every way. The finish of action and barrel was every bit the equal of London magazine rifles from Lancaster or H&H. The stock on the M-10 is as good as anything from that era, and vastly better than most. It is slim, graceful, handles like a fine shotgun, and comes up to the shoulder with the eye perfectly aligned with the sights. Both wrist and forend are slim by any standard, and it had extensive, well-executed, wrap-around checkering.

According to the Ross catalogue, all sporting models were stocked in Italian walnut. The contoured steel buttplate is checkered, the grip cap is horn, the forend has a delicate Schnäbel. As with most rifles of the time, makers believed there should be a forend screw to attach it to the barrel, and this belief did not die quietly. (This somewhat archaic feature lasted on the Winchester Model 70 until 1963.) On the Ross, this screw goes through the wood into a barrel band. On my rifle, the forend screw itself is the forward sling eye but, inexplicably, it has no rear sling swivel as shown in the catalogue. However, Ross sporting rifles were a semi-custom proposition, so the original buyer may have specified this for whatever reason.

The rifle has a box magazine flush with the stock. Like the Mauser, the floorplate is removable with the nose of a bullet or similar tool. Otherwise, cartridges must be unloaded by working them partly into the chamber, also the same as with a Mauser. The barrel is carbon steel, 28 inches long, although it could be ordered with a 26-inch barrel. The rate of twist was advertised as 1:8.66 inches, more than sufficient to stabilize the heaviest bullet at Ross velocities.

One of the most interesting features about this rifle is its sights. As it came standard from the factory, it had a fine bead front sight on a barrel band, and a single-blade rear sight, also on a barrel band. The blade has one number on it: 500. This blade could be either fixed or folding. It was possible to order the rifle with a telescopic sight; unlike the Model 1905, the “Ross Model of 1910 Action,” as it was formally known, had a receiver bridge to accommodate a peep sight, if desired. According to the catalogue, which is replete with charts, graphs, and explanations, the trajectory of the .280 Ross was so flat that the single blade served for all distances out to 500 yards simply by the accepted expedient of taking a fine or a full bead.

Major Sir Gerald Burrard (mentioned in the previous chapter) was one expert who greatly admired the .280 Ross cartridge, but did not agree with the principle of “fine or full” beads, and questioned the performance claimed for the cartridge. Sir Gerald believed that an experienced hunter should acquire the same sight picture each time, and then either hold high or low, depending on the range. Testing a Ross rifle with the 500-yard sight, he found that holding dead on at 100 yards placed the bullet eighteen inches high. Keeping in mind his aversion to “fine or full,” however, these two statements more or less cancel each other out.

Sir Charles Ross set out to design “the greatest hunting rifle the world has ever known.” With the Model 1910, he came very close indeed. It is a beautifully made and finished, well balanced rifle with a superb hunting stock.

Not surprisingly, given its record on the target ranges of the world, the Ross company placed great emphasis on the accuracy of its rifles and cartridges. Captain Crossman, who was at one time high-power rifle-shooting champion of California, claimed to have shot groups at 500 yards that measured four to seven inches. His rifle was fitted with a 3.5X Pernox riflescope. Townsend Whelen, on the other hand, reported that he took six rifles from a dealer’s stock, spent a day shooting them at 200 yards, and averaged ten-shot groups of about eight inches. Some writers backed Crossman, others supported Whelen.

In spite of this, Whelen stated in print that the Ross M-10 “just might be the kingpin of all rifles.”

* * *

The M-10 bolt has controlled-round feed, like the Mauser 98, with the extractor picking up the case as it is pushed forward out of the magazine. The ejector is a spring-loaded triangular projection, unobtrusively low on the left side, just forward of the bridge. The M-10 safety catch is a small wing on the bolt handle that locks the striker, is easily manipulated by thumb alone, on or off, and can be absolutely silent.

The Ross trigger is the standard (for the time) two-stage military-type, with a reasonably light, crisp release. It was designed in such a way that, if the action is not completely locked up when the trigger is pulled, the force of the striker spring serves only to push it closed the rest of the way. When the safety is on, the trigger moves easily. The trigger is not blocked by the safety; instead, the safety pulls the striker back from any contact with the sear.

The receiver bridge houses the bolt stop, which is a knurled catch. The 1914 catalogue states bluntly that the bolt stop is copied from the 1906 Springfield, but then makes the startling statement that Ross sporting rifles have “no magazine cut-off,” and goes into some detail as to why the company believed magazine cut-offs were a mistake on hunting rifles. And yet, the bolt stop on my M-10 has three positions, and in its third (up) position it does act as a magazine cut-off. Down all the way, operation is normal; at mid-position, the bolt can be removed; up all the way, it projects slightly forward, blocking the bolt from coming completely to the rear. This ejects the empty case, but prevents the bolt from picking up a round from the magazine. In this way, the rifle can be used as a single-shot, while keeping the entire magazine in reserve, or in order to switch to different ammunition quickly, without emptying the magazine. One more contradiction, as if there were not enough already.

Sir Charles Ross, and of course his collaborator, F. W. Jones, were as interested in bullet design as they were in every other aspect of shooting. Their work with long-for-caliber bullets, and extra-low drag bullets, especially for long-range target shooting, was hugely influential, and bullet designers are building on that foundation to this day. Ross also designed hunting bullets that were revolutionary. Among the hunting bullets with which the .280 Ross was loaded, two stand out. One was a jacketed hollow point, the other was his famous “copper-tube” bullet that employed a spitzer tip of copper that, on impact, drove down into the lead core and caused the bullet to open up. This was not a new idea even then, Westley Richards having used the concept with bullets for black-powder cartridges. The Ross, however, was a streamlined, deadly, ultra-modern bullet that would not look out of place in a bullet catalogue of today. The idea was adopted in the 1960s by Canada’s Dominion Cartridge Co., and marketed as the Sabre-Tip, as well as by Remington (Bronze-Point), Nosler (Ballistic Tip), and dozens of others in recent years. More bullet makers are adapting the design all the time.

.280 Ross cartridges, from left: 145-grain “copper tube” hunting bullet, 160-grain hollow point, and 180-grain match.

The cartridge itself was the most influential ballistic development of its day. Sir Gerald Burrard considered it to be a watershed. When it appeared, he stated, it “changed everything.” He himself used the .280 almost exclusively in the Himalayas, but did so in a Charles Lancaster double rifle with oval-bore rifling because he vastly preferred the advantages of a double. As well, the oval bore minimized the effects of “nickelling”—fouling resulting from firing cupro-nickel jacketed bullets at high velocity.

The interrupted-thread locking lugs which caused problems in the Ross Mk. II** were undoubtedly every bit as strong as Ross claimed. They withstood proof pressures up to 150,000 psi, according to Roger Phillips, and when Charles Newton designed his own rifle in 1915, he employed the same principle. In fact, Phillips states that the Newton bolt head was a “direct copy” of the Ross. Since then, it has been used on various semiautos. The Weatherby Mark V’s nine-locking-lug configuration, introduced in 1958, is a variation on the theme of the interrupted thread, and is acknowledged to be extremely strong.

Even after its replacement by the Lee-Enfield in 1916, the Ross continued to be used by Canadian soldiers, and especially snipers, in the trenches. It was the most accurate rifle employed by any nation in that war, and if you looked after it, knew how to use it, had the alteration made to the bolt stop to avoid peening, and were careful about ammunition, a sniper such as Herbert W. McBride (A Rifleman Went To War) could use it to devastating effect.

After the war, Ross rifles found their way to the four corners of the earth, usually as small lots of surplus military rifles bought by desperate countries or paramilitary forces. When the Canadian Army switched to the Lee-Enfield in 1916, its Ross rifles were given to Britain in a “straight swap.” With several hundred thousand Ross rifles in storage, Britain gave some to the Royal Navy, armed some home-defense units with them, and hauled them out in 1940 in preparation for an anticipated German invasion. Between the wars, the Baltic states (Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania) were supplied with Ross rifles, while others went to Russia in the 1920s and were used in the long post-Revolution civil war. Years later, these resurfaced—reworked, restocked, and with new sights—and were used by the Russian shooting team to win the international running-deer competition in Caracas, Venezuela, in 1954.

Here is an interesting point that jumps out from all the accounts of Ross sporting rifles and their mishaps: None that I can find were reported before 1914, when the war began. All of the civilian claims date from after 1918, after the widely publicized controversy over the performance of the military rifles. This is very strange, not to say suspicious, given the fact that the sporting Ross M-10 was in use, all over the world, from 1910 onwards with, to all appearances, nary a misstep. Before 1914, it was all glowing accounts of great successes, from three grizzlies downed in less than a minute to an elephant dropped at 400 yards with a 180-grain solid. After 1918, it’s all injury claims and lawsuits.

In 2002, Gun Digest published one of the best-balanced articles about the Ross, written by Jim Foral. Foral spent an entire summer shooting Ross rifles and loading ammunition for them. He is a diligent researcher who makes a specialty of delving into what appeared in print a century ago, in such publications as Outdoor Life and Arms and the Man.

Among the writers quoted by Foral from original publications are Capt. Crossman, Capt. (as he then was) Townsend Whelen, and Maj. Charles Askins Sr. He also quotes a “Canadian gun writer” by the name of Linsey (or sometimes Lindsey) Elliot (one “t”)—presumably the same Lindsay C. Elliott mentioned by Roger Phillips, whose letter to H. V. Stent at Outdoor Life described the death of a Canadian soldier in the trenches. Since Phillips identifies Elliott in some detail, we can assume his full, correct name was Lindsay Clinton Elliott. Incidentally, one more minor mystery: if H. V. Stent was writing for Outdoor Life in 1922, he must have been a writer of extraordinary longevity. His byline appears in Gun Digest as late as 1980, and Rifle Magazine as late as 1986. Or, perhaps there was more than one firearms writer named H. V. Stent.

Elliott first appears in print as a resident of Carbon, Alberta, who describes his Ross rifle in glowing terms. Foral quotes him as saying the stocking and checkering were “of the very best,” while the stock shape was excellent for managing recoil and “the balance of the rifle is perfect.” Elliott tests some soft Dominion Cartridge Co. ammunition, which also gave Crossman fits on a hunting trip. The brass was soft, stuck in the chamber, and was extracted only with great difficulty. Elliott reported the same experience, but says that overall he liked the rifle “a whole lot, and hated it just a little.” All he had “agin’ it,” he wrote, was the sticking bolt.

According to Phillips, Lindsay Clinton Elliott served in the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps (RCOC) as an armourer-sergeant from 1915 to 1919. Elliott claimed to have originated the practice of putting a rivet in the Ross bolt housing, to prevent the kind of misassembly that resulted in accidents. At the time, he was said to have been serving with the 6th Canadian Infantry Brigade under Brigadier A. C. Macdonnell. However, Brig. Macdonnell commanded the 7th Brigade, not the 6th, so where did Elliott serve? Brig. Macdonnell and his officers were the most vociferous in condemning the Ross, leading up to its replacement in 1916. After the war, Elliott went to work for Canadian Industries Ltd. (CIL), which manufactured ammunition under the Dominion brand for the next sixty-five years. Elliott was employed by CIL for twenty-five years, giving sales demonstrations.

The thorniest issue involving Ross rifles, both military and civilian, is the claim that the bolt could be misassembled in such a way that it could be put back into the rifle, chamber a round, appear to be locked when it was not, and then blow back out of the rifle, injuring or killing the shooter.

It has been demonstrated that this can be done, but it is not easy to do, and the bolt does not slip readily back into the action. Even this controversy has survived for a century, with some authorities in the 1940s claiming to have done it, while others denied it was possible. A few years ago, a short video appeared on the internet showing a man accomplishing it with a military Ross, albeit with considerable difficulty.

It is usually described much as O’Connor wrote: “The bolt can be incorrectly assembled . . .” as if this were as easy as putting your shirt buttons in the wrong holes. It is anything but. Disassembling a Ross bolt in the first place is far from simple, and soldiers in the trenches were expressly forbidden to strip their rifles beyond a certain point, after which they were to be handed over to the armourer for repair. Supposedly, in the mud of the trenches, soldiers disobeyed this in a desperate effort to get their rifles working when they were choked with mud.

The Ross bolt operates inside a sleeve, rotated the way a ratchet screwdriver rotates its head. When the bolt mechanism is removed from the rifle, the bolt is all the way forward and protrudes from the housing by .93 inches. When replaced in the rifle, the bolt lugs come in contact with the barrel, and are then rotated into the locked position as the bolt housing continues forward. With the mechanism out of the rifle, however, the bolt can be rotated by hand, and is then drawn back into the housing by the striker spring. As long as the extractor remains in its groove forward of the lugs, all will be well. The bolt can be moved in and out at will. However, the extractor functions in a manner very similar to the extractor on a Mauser 98, and like the Mauser, it can be rotated out of its groove, allowing the bolt to retract slightly, then rotated back into its groove. Now the bolt is too short, and will not close properly. Is this confusing enough for you?

Actually accomplishing this is not nearly as easy as it sounds, and if you do manage it, the bolt does not slip effortlessly into the rifle. It binds, jams, and needs to be forced in. Jim Foral quotes Herbert Cox of Wilmington, Delaware, who, in a letter to the “Dope Bag” section of the Rifleman in 1945, stated he had mastered the technique, but not without considerable difficulty getting the bolt into the rifle, and then getting it back out only with the aid of a screwdriver and both hands, with the rifle locked between his knees. Roger Phillips confirms that Cox was one of America’s foremost authorities on Ross rifles until his death in 1964, and that he had pinpointed several ways in which the bolt could be altered to prevent misassembly.

Keeping the bolt correctly and permanently aligned in its sleeve was relatively easily done, with a rivet or screw in the right spot. All of this, of course, is the kind of teething problem that arose with the Lee-Enfield in its formative years, and was corrected through various marks and asterisks as a result of troop trials. As Lt. Gen. Edwin Alderson, then commanding the Canadian Corps, wrote in a letter in early 1916, “The Lee-Enfield is an old experienced man as a service rifle, while the Ross is a baby.” Lt. Gen. Alderson was, indisputably, treated very unfairly by the Canadian government, and removed from command shortly after he wrote that. It is probably unwise to comment on what appears on the internet, in such places as Wikipedia, since it could disappear tomorrow or be radically changed, but an entry devoted to Lt. Gen. Alderson refers to the Ross as “useless in the trenches.” It certainly had its faults, but it was far from useless, and when Field Marshall Haig ordered it replaced in early 1916, it was mostly because Canadian troops had lost confidence in it; the mechanical problems themselves had already been largely corrected.

This is a good place to insert the fact that, were I to find myself in the trenches of Flanders in 1915 and had a choice, I would take a Lee-Enfield No. 1, Mk. III over the Ross with no hesitation whatever. The Lee-Enfield was unquestionably one of the finest battle rifles of the twentieth century.

* * *

Jim Foral also quotes a Canadian firearms authority from the 1940s, C. C. Meredith, as saying,“As to the safety of the Ross action, more nonsense has been written than you can shake a stick at.” After exhaustive research that would have driven lesser men to the bottle, Roger Phillips and his co-authors concluded that:

“Generally speaking, a Ross rifle with the 1905, 1905 modified, and 1910 actions are safe to use if they have not been tampered with after leaving the factory, are used with ammunition designed for them, and are in the hands of users who actually know the rifle.”

I cannot claim to know the Ross as well as I would like to. I still struggle every time I try to deliberately misassemble the bolt and get it back into the rifle. I still wince inwardly when I pull the trigger on a live round, even though I know—know—that the bolt cannot just “slip” into a misassembled and dangerous state.

But pick up the M-10, look at its checkering, put it to the shoulder, work the bolt back and forth a few times, dry-fire it once or twice, heft it in your hands, and you know you’re handling a thoroughbred. As a hunting rifle, it was well thought out from stem to stern. Those careful thoughts were then transformed into walnut and steel to the best standards of the London gun trade, by craftsmen who really knew their work. It is beautifully balanced and fits every bit as well as other rifles mentioned in this book—and it preceded most of them, and set an example for others to follow. Stocks on American custom rifles did not catch up to the Ross M-10 for twenty years, and to this day, most are still not as good.

It’s impossible to consider any of Ross’s accomplishments separately from his failures, but we can say for certain that in the .280 Ross cartridge, Sir Charles created the first and one of the finest of the 7mm magnums, and that he set in motion a train of events that led to Charles Newton, Roy Weatherby, and the modern high-velocity hunting cartridge. As it nears 110 years old, however, the .280 Ross is more than merely a cartridge. It’s part legend, part hero, part villain. As a designer of both rifles and cartridges, Sir Charles Ross, Bt., deserves more credit than he receives. Brilliant, erratic, talented, impatient—he was, to put it bluntly, a spoiled brat who grew up sublimely intolerant of others. To Sir Charles, ironing out bugs was detail, and he had no time for detail.

The .280 Ross (extreme left) inspired a host of similar 7mm cartridges, including (from second left) the .280 Magnum (Rimmed Ross), .275 H&H, and .275 H&H Rimmed, also known as Holland’s .275 Magnum. There was also the short-lived military .276 Enfield and, later, the .280 Halger, 7mm Mashburn, 7x61 Sharpe & Hart and, finally, the 7mm Remington Magnum.

One can hardly write about the .280 Ross and not get lured into Sir Charles Ross’s life, loves, character, and accomplishments. It’s easy to be distracted by the Ross rifles and their record on the target ranges of the world, or in the trenches of the Great War. One could also look at Ross’s work in bullet development, the evolution of smokeless powders, and the search for higher velocities. He was an original and, even among the British aristocracy, wherein there has never been a shortage of eccentrics, he cut a swath at which we can only marvel.

No history of great hunting rifles can possibly ignore either the .280 Ross or the M-10 sporting rifle. They were too revolutionary, and too influential, for too long. Is it really a “great” hunting rifle? In the right hands, yes. But there is always that caveat. To be on the safe side, we’ll say yes, and put an asterisk beside it. Which seems appropriate.

In a bizarre sort of the way, the Ross M-10 rifle and the .280 Ross cartridge are inanimate reflections of the man himself: brilliant, contradictory, controversial—but fascinating.

During his last illness, aged seventy, at his home in St. Petersburg, Florida, Sir Charles Ross’s last words were addressed to the nurse who was attending him. He opened his eyes, muttered “Get the hell out of here,” and died.

Savage Model 99E.