SCOPES AND MOUNTS

The invention and perfecting of the telescopic sight was truly one of the great advances in riflery, but it was not without cost. Scopes add to the weight of a rifle, they increase bulk and make it more awkward to carry, and they slow down reaction time when a quick shot is needed. Older scopes fogged up in rain and cold, and any scope can go off zero with no warning or indication that anything is wrong until you miss an easy shot.

For riflemakers, scopes added the problem of how and where to mount them, as well as how to make the rifle’s mechanism function around them. Some rifles never could be adapted very well—the Winchester 94 is probably the best-known example—while others presented chronic difficulties in one respect or another.

Although scopes were used on long-range rifles as far back as the Civil War, and by Lt. Col. David Davidson in India thirty years before that, it was a century before they came into mainstream use. Early scopes were long, heavy, and relatively fragile. Generally, they were seen only as complementing open sights, not as the main sighting equipment. European rifles before 1914 favored detachable scope mounts that allowed the hunter to carry the scope in a case, and install it on the rifle only when it was needed, or as circumstances warranted. For everyday use, the rifle had iron sights.

In America, it took even longer for the hunting riflescope to make its appearance, and when it did, it was usually German- or Austrian-made. It was not until the bolt action displaced the lever rifle as the favorite for hunting that scopes really became popular.

Because of the way scopes were used in Europe, gunsmiths developed detachable mounts, with the claw mount being the most common. Claw mounts come in many shapes, sizes, and configurations, and from the beginning were a custom feature that did not lend itself to mass production. Essentially, there are two sets of claws, one on each scope ring, and they snap into recesses in the bases which are attached to the receiver bridge, ring, or even out on the barrel. One set of claws has a spring-loaded latch that snaps into place as they are pushed home.

Claw mounts can be very exact or very sloppy. The steel can be properly hardened or left soft, allowing excessive wear and, eventually, loss of accuracy. The Teutons being Teutons, no complicated variation was too outlandish. In addition to having a mount that allowed the scope to be removed, some gunmakers liked to have a mount that also allowed the use of the iron sights without removing the scope. They mounted them very high, with tunnels through the bases through which the shooter could line up the iron sights. This can be traced to an innate distrust of glass. Most of us, when we think “glass,” subconsciously think “break.” Because glass is an integral part of a scope, hunters were afraid it would shatter, crack, fog up, or otherwise malfunction, and insisted on a back-up system. American hunters had similar fears, although they did not go to the same lengths to allow for any eventuality. It is no accident that some of the custom side mounts made in the USA, such as the Jaeger and the Pachmayr Lo-Swing, were designed by German gunsmiths.

Claw mount on early Mannlicher rifle. The claws, front and back, fit into recesses in the bases. Painfully simple, but extremely good.

The Pachmayr Lo-Swing mount, on a Mannlicher-Schönauer Model 1956.

The Pachmayr Lo-Swing can be rotated out of the way to allow the use of iron sights, or removed completely. This Mannlicher-Schönauer Model 1950 was originally fitted with a claw mount (the front base is visible). Either the scope and rings were lost somewhere along the line or the owner wanted to use a more modern scope.

This is not intended to be a history of riflescopes and scope mounts, only to show how scopes can improve or detract from a good hunting rifle. What we have to remember is that when we put a scope on a rifle, we are essentially taking two mechanisms and bolting them together. It can be done in such a way that it’s either a net gain or a net loss, depending on whether the two mechanisms complement each other. Some rifle and scope combinations I’ve seen resemble a farm tractor with a Rolls-Royce Merlin bolted onto its chassis, not only rendering it useless for its original purpose, but for any purpose whatsoever aside from being a curiosity.

In the modern age of riflescopes that are wondrous optical instruments, the practice of “over-scoping” is almost epidemic, but it’s not a new phenomenon. In the 1960s, hunters would decide to scope their trusty Winchester 94, in the admirable but admittedly limited .30-30, and contrive some mount that would let them put a big 3-9X variable scope on it. No .30-30 ever made benefits demonstrably from having a nine-power scope. By adding it, they made their rifles heavier, awkward, and much more difficult to carry. At three-power, they may have gained a sighting advantage within the .30-30’s practical range, but that’s where it ended.

There is a tendency among teenage boys and newcomers to the shooting game which has been noted by several generations of gun writers. It bears repeating for the simple reason that the phenomenon keeps resurfacing with every new influx of shooters. This tendency is a desire to allow for every eventuality by providing the maximum in versatility in rifle, sighting equipment, and even caliber. Complicated gizmos appeal to those who have done little hunting but are fond of planning, in theory, the perfect rifle. For those who have climbed mountains, hunkered down in long grass, and gone into the bush after a wounded animal, the qualities that appeal are simplicity and reliability.

Let’s look at a hypothetical case of one of these rifles as imagined by a gun-struck teenager. Actually, it is not entirely hypothetical, since about thirty years ago I received a seven-page, typewritten letter from a boy outlining his thoughts on the matter, and I realized to my horror that they reflected my own attitude when I was his age. Since the possible variations and permutations are almost endless, down to and including interchangeable barrels, bolts, and magazines, for the purposes of this lesson in horror stories we will just stick to the sighting equipment. Here goes.

The rifle, a .300-.338 Thunderstruck Super-Ultra Magnum, will have the usual open sights, but the front sight will have a folding “moon” sight for dangerous game in low light. There will be a standing leaf on the barrel, with four folding leaves for ranges from fifty to five hundred yards. We will add a detachable aperture sight on the receiver which, when not in use, will be stored in a tiny compartment accessed through the pistol grip cap. The scope will be fitted in a detachable mount, but the rings will have tunnels bored through so we can use the iron sights without removing the scope. Since the scope can be removed, however, it allows us to get three different scopes with suitable rings. We can then choose which scope to mount depending on what and where we are hunting.

Sound feasible? Actually, it’s a nightmare.

It would be interesting to know, of all the guys with detachable mounts and iron sights, exactly how many have actually sighted in the iron sights with the same ammunition for which the scope is set. If I had to guess, I would say it would be 10 percent or less—possibly much less. I believe this because, more than once, I have found myself leaving for a trip with a scope-sighted rifle and carefully handloaded ammunition, only to realize that I have not taken the scope off and checked where that ammunition prints with the iron sights. It’s one of those things that always gets left to the last minute, if you think about it at all, and generally never gets done. In the case of a dangerous-game rifle, which is where iron sights are most likely to be used in today’s world, this is a frightening thought.

Even something as seemingly simple as making sure your variable scope prints to the same point of impact, regardless of power setting, seems to find itself on the “forgotten” list. This is not as much of a problem today as it was with the first variables, but it still happens and should still be checked. At the very least, knowing that your scope is dead on at all settings will increase your confidence, and reduce the chances of an attack of jitters when a big bull steps out of the bushes.

A few years ago, I was on a hunt for driven big game in Germany, as the guest of Zeiss, the optics giant. There were about forty of us altogether, from a dozen countries, and all very experienced big-game hunters. We were provided with new Sauer 404 rifles in .30-06, fitted with the latest 30mm, 2.8-20x56 scopes. As an experiment, at the end of the hunt when the rifles were being gathered up to return to the factory, I did an informal check of all the power settings on those scopes. With one exception, they were set from 2.8X to 4X; the exception was one set at 5X. I made a point of asking the two most successful hunters there, who were from Norway and Denmark, what power settings they had used. Both shrugged and said, “Something low. I don’t know exactly.”

That is a big, heavy scope. Optically magnificent, of course, but for the hunting we were doing it was unnecessary. In fact, it added so much weight to those Sauer rifles with their sexy but awkward thumbhole carbon-fiber stocks, that they were not easy to handle in the small, closed-in stands. In driven hunting, the key is to be ready to shoot at any second, and often at a fast-moving target. Those scopes, made for very deliberate long-range shooting, were actually a liability. At the time, I thought to myself that, if I were outfitting this crowd, I would give them light .308 Winchesters with a 2-7X or 1.5-6X, one-inch scope. That pretty much describes the favorite hunting rifle of my friend Jørund Lien, from Norway. We have hunted together in Sweden, Poland, and Germany, and he is one of the best hunters I’ve ever seen. He does a lot of driven shooting, as well as stalking in the Norwegian Alps, and uses a light, short-barreled .308 Winchester fitted with a low-power variable.

A German EAW side mount on a Mannlicher-Schönauer Model 1956. The scope is detachable, and sits very high to allow space for the bolt to clear. The unique cheekpiece of the Model 1956 allows the eye to slide up or down comfortably to accommodate either the scope or open sights.

There are two factors at work in what I perceive as this epidemic of over-scoping. One is lack of experience on the part of many shooters, who believe that more and bigger is always better; the other is the relentless dick-measuring contest that takes place constantly on rifle ranges. When you get a new rifle, the first place anyone will see it is at the range when you go to sight it in. Inevitably, someone will pull out a rifle with a bigger scope on it, to show that he has something better. It’s not better, of course, but you always find yourself trying to justify investing in something smaller, lighter, and lower-powered than the lunar telescope he has mounted on his super-magnum, complete with bipod, sniper sling with eighteen different straps and buckles, and a cartridge case taped to the buttstock. He may think he’s the second coming of Carlos Hathcock, but usually such an outfit just shows nothing more than inexperience.

* * *

Choosing an inappropriate scope to put on a rifle can turn it instantly from an ergonomically sound, graceful, and deadly instrument for hunting, into an awkward beast with sighting equipment that actually makes it less likely that you will be able to hit anything.

The Marlin 336 provides an excellent example. In its original form, the 336 is a fine stalking rifle, similar to the Winchester 94. It carries easily, balanced in one hand where it’s instantly available if a deer bursts out of the bushes. One advantage of the 336 over the 94 is that, with its side ejection, a scope can be mounted low over the receiver. Once you do that, however, the rifle no longer carries so easily in the hand. It doesn’t matter what size the scope is, it interferes with that natural “trail” carry. The answer for many is to fit the rifle with a sling, so it can be carried on the shoulder, and that is where it will ride forevermore. And when a deer bursts out of the bushes? You don’t have a chance at a shot because your rifle is hanging on your shoulder instead of in your hands, where it should be.

In recent years, riflescopes have unquestionably become optically superior to what they used to be. Today, it is a rare scope that leaks or fogs up, regardless of conditions. The glass is better, the coatings are excellent, reticle adjustments are positive and stay where they’re put. Most scope tubes are made of aluminum or some other alloy, which reduces weight without unduly reducing strength. The really top scopemakers, like Swarovski and Zeiss, have coatings that cause lenses to shed water so they never need to be wiped dry. To me, that is vastly more useful on a hunting rifle than an extra 1 percent light transmission. Variables have expanded their range of powers; where in the old days we had a three-to-one ratio (2-7X, 3-9X), scopemakers began pursuing greater ranges. As of today (and who knows what it will be tomorrow?) the greatest range is eight to one, meaning a scope can be a 1-8X, 2-16X, 3-24X, and so on. Finally, scope tube diameters are larger. Today, 30mm tubes are common. Most of us assume that means greater light transmission for better low-light visibility, but they are also required for those high power ratios mentioned above. Another advance is the illuminated reticle, usually in the form of a red glowing dot or cross at the center of the aim point, and a 30mm tube affords more room for the electronics required for that.

This detachable mount by Joe Smithson is on a custom .375 H&H rifle, with a Zeiss 30mm scope. It is beautifully made—one of the most elegant of scope mounts.

Now for the disadvantages. Scopes with 30mm tubes and large objective lenses are heavier and bulkier. Adding an illuminated reticle means there is a mechanism that can malfunction, with a battery that can go dead when you need it most. High power ranges are a questionable asset. How many times would you need to have both a 2X and 16X available on the same rifle? If you only need 2X, or maybe as much as 6x, you are carrying all that extra weight and bulk to give you something you’ll never use, and it will make the rifle slower to handle. You also run the risk—and this is no small thing—of having the power setting at 16X when you need to make a quick shot on a moving target at a few yards. Good luck.

Another factor to be considered is eye relief. As power ranges expand, ocular bells get longer. Manufacturers insist that eye relief is more than ample, but sometimes you’ll find you can’t mount the scope far enough forward to make use of that eye relief and have your head and eye in a natural, comfortable position on the stock. To keep your eye away from that long ocular bell, you have to contort your neck to get your cheek down on the stock, far enough back.

Years ago, I espoused the idea of paying a lot of money for the best scope (buying one good one instead of three cheaper ones), and getting a wide enough power range that the scope could be switched around from rifle to rifle, depending on which one I wanted to use that day. It didn’t take me long to grow out of that. Every good hunting rifle needs its own scope, tailored to its particular uses, mounted and left in place. The idea of switching scopes around may be good in theory, but it ain’t very good in practice.

With the recent fascination with all things military, and especially all things sniper-related, scopes have gone off the deep end in terms of size and power. Now, instead of 30mm tubes, we have scopes with 36mm tubes. For example, the Zeiss Victory 4.8-35X has a 36mm tube and a 60mm objective lens, illuminated reticle, weighs over two pounds (thirty-four ounces) and sells for around $4,000. For $4,000, you could buy four excellent—and I mean first-rate, top-notch, and A-number-one—hunting scopes, and still have money left over. There is no genuine hunting rifle I can imagine that would require that Zeiss Victory. And no, it would not double as a spotting scope. Potential targets should be viewed with a binocular. It is a little jarring to find you’ve been scoping out an unknown movement in the distance with your finger near the trigger, only to learn it’s someone out walking with his dog.

Along with this headlong rush to the unergonomic, there has been a cascade of wild designs in reticles. We have always had complicated reticles, going back to the 1960s when we saw the first “rangefinder” reticles with multiple crosswires. Today’s creations bear about as much relation to those reticles as an F18 does to a Sopwith Camel. There are reticles available now that literally fill the entire field of view when you look through the scope. The military began this trend with the mil-dot system (which few civilians really understand, and no civilian needs) but scopemakers and reticle designers have left all semblance of common sense behind in their rush to make these as complicated and confusing as possible. Needless to say, they have made such scopes less usable for hunting, rather than more.

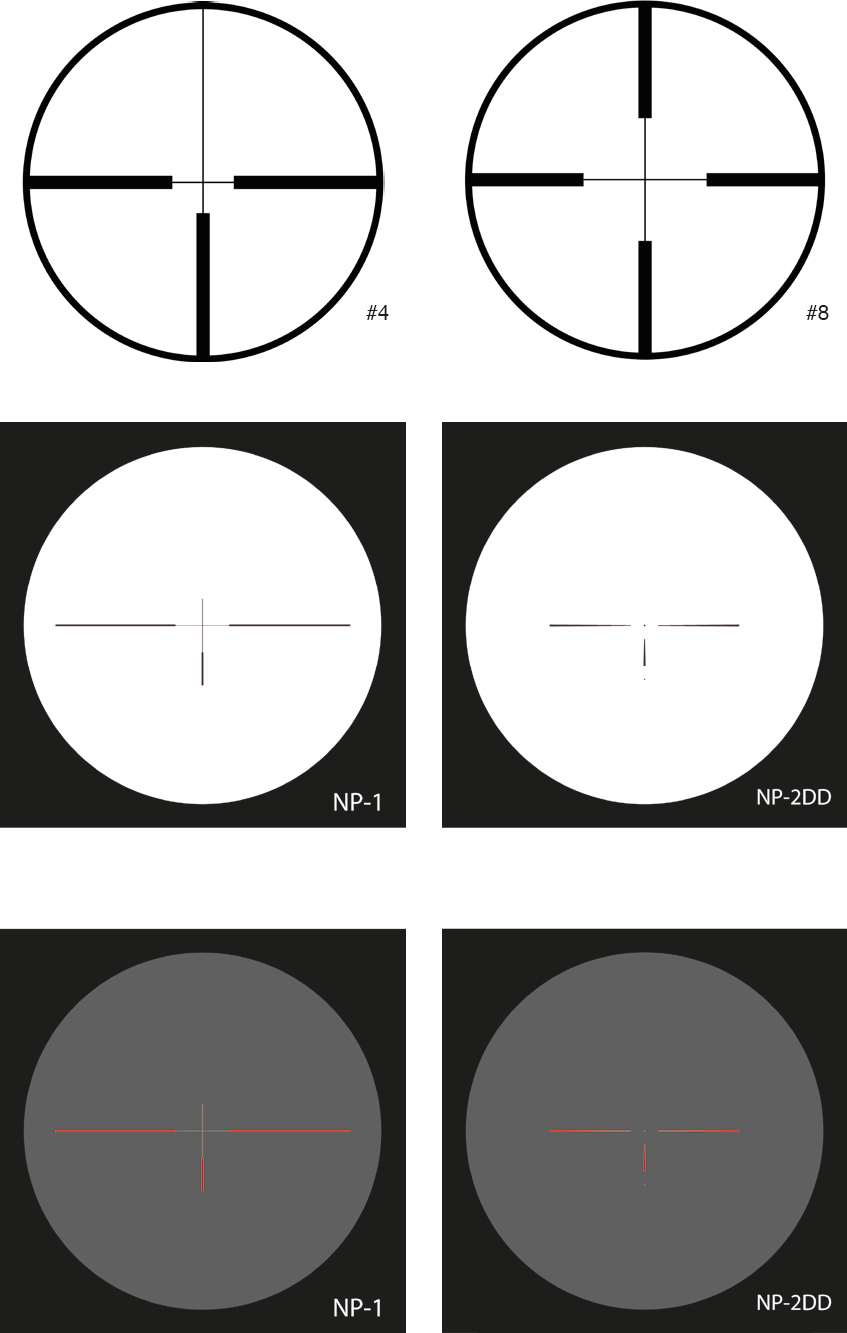

A selection of reticle designs, old and new: The German #4 reticle has a crosshair and three posts, the #8 a crosshair and four posts. The #8 is a forerunner of the Leupold duplex reticle, now copied by virtually everyone. Nightforce has engineered some innovative and very good reticle designs, incorporating the principles of the simple crosshair or duplex with illuminated reticles.

For my money, the best reticle ever designed for a hunting scope is Leupold’s duplex, now copied by virtually everyone. A duplex is a simple crosshair with the horizontal and vertical wires thin in the center, thicker on the outer ends. The duplex may have been made popular in America by Leupold, but it was in use in Europe much earlier. A remarkably similar reticle is shown in the 1914 Charles Lancaster catalogue. Add an illumination feature that lights up the thin, center wires and you have an almost perfect arrangement. Reticle preferences are as personal as blondes versus brunettes. One principle does apply, however: When you need to make a quick shot, the reticle should help you, not hinder you.

In the days when it was still a big name in high-quality hunting optics, Bausch & Lomb introduced the first great variable, the Balvar 8. It had one of the simplest but most ingenious reticles ever devised. In those early days, the reticle was always in the first focal plane, which meant it grew larger and smaller as the magnification varied. B&L solved that problem with a reticle that was like a simple crosshair. Instead of thin wires, however, it consisted of four extremely narrow black triangles, thicker at the outer edges and dwindling to nothing at the center. As power changed, the reticle stayed exactly the same in the center. It was an optical illusion, but who cares? For a while, other scopemakers offered this reticle as an option, but it seems to have disappeared. Since most reticles now are in the second focal plane and never change size anyway, it’s not necessary.

The above is true of hunting scopes. In tactical or target scopes, however, where reticles are increasingly used for additional purposes such as gauging distance, the trend is now back toward reticles in the first focal plane. This leaves the relative measurement the same regardless of magnification. Thirty years ago, the “in” thing was second focal plane; now the “in” thing is back to first focal plane. On a hunting scope, however, the reticle in the second plane is vastly superior.

Some military reticles, intended for snipers, allow you to shoot at different ranges, using different intersections of lines, or allow for wind by moving to auxiliary vertical lines to the left or right of center. These are all very well for sniping situations where the shooter has a lot of time to calculate, settle in, decide on which intersection to use, and then take all the time he needs to squeeze off the shot. They are a decided disadvantage when you are trying to pick out a moving bull elk on the edge of a clearing, in failing light with snow falling. One highly visible reticle, in the center, thank you very much and I’ll decide whether I need to hold a little high or a little low. That’s the reality of hunting.

Another disadvantage of larger scopes is that, not only do they need to be higher over the rifle’s action to allow room for the large objective lens, placing them higher gives their weight more leverage to work on the scope mounts under recoil. Higher and heavier scopes present difficulties. Combine this with heavier recoil, and you can really have problems. And no, a muzzle brake is not the answer. All a muzzle brake does is turn two recoil impulses into three. You may not feel it that way, but your scope mounts certainly do.

Before moving on, we should take a look at what the future might hold for riflescopes. In 2004, an electronics manufacturer showed up at the SHOT (Shooting, Hunting and Outdoor Trade) Show, with a new scope they expected would sweep the world. It was not a riflescope in the conventional sense, although it vaguely resembled one. Actually, what it looked like was the original range-finding riflescope introduced by Swarovski in 1995, and abandoned soon after. It was a long, square tube. Instead of looking through it, it was a video camera that produced its image on what we would call the ocular lens, which in turn was rectangular like a television. And that’s what you were looking at: a small TV screen. This contraption allowed the user to design his own reticle and program it in, or have different reticles for different situations. It allowed you to film your shot (and kill) when you took aim and pulled the trigger. It could download information from a satellite. The price at the time was around $3,500, which was outlandish for a riflescope in 2004. In the display booth, two non-hunting, video-and-computer geeks stood by to explain its workings to the passers-by.

That particular invention seemed to disappear—at least, I never saw it again, thank God. But the idea of a riflescope that can talk to a satellite, downloading information like weather conditions, atmospheric pressure, or even ballistics data that will automatically program the scope, is not far-fetched in the least. The European scope manufacturers are at war with themselves, producing such gizmos on the one hand, but preaching ethical hunting practices on the other. They argue that they do not encourage shooting at extreme ranges, even while producing scopes that encourage you to try it. They also argue that, if people must shoot at those ranges, with a rangefinder and high-power scope they have a better chance of a clean kill. I would argue that, the world being what it is, such equipment only increases the chance of wounding the animal, rather than missing it cleanly. Take your choice as to which argument you buy.

This is as good a place as any to look at exactly how much sniper technology and techniques can be applied to hunting rifles. The short answer is: they cannot. Today’s snipers are ultra-specialists, trained in all manner of military skills, tuned to a high pitch. They work in teams, with one man on the trigger and one (or more) in supporting roles, calculating trajectories, measuring distances, judging wind, and so on.

The major difference between a sniper and a big-game hunter is that the sniper really doesn’t care if his shot kills his target, cleanly or otherwise. A live enemy with a ghastly wound will do nicely, and fulfills the psychological aims of sniping just fine. It not only removes a combatant, it gives the enemy logistical problems looking after the victim. Plus, it’s bad for their morale.

A big-game hunter with even the most cursory grasp of ethics, however, wants to make a clean, quick, painless kill with one shot, if possible. Even a meat hunter who doesn’t care whether it’s a buck or a doe wants a clean kill, so the meat will be good.

There are shooting schools that teach hunting courses based on everything from street-fighting techniques to SWAT teams bashing in doors, and claim that this is good training for hunting animals like Cape buffalo. They use ARs with tactical slings, holding the rifle straight up and down in front, and moving in approved military fashion. There are also those, mostly veterans of wars but without much hunting experience, who claim that “having hunting armed men,” they are ready to take on lions or elephants. Piece of cake.

Detachable mount on a new “Original Mauser” Magnum 98, introduced in 2015. This is a variation on the Redfield/Leupold dovetail mount.

Detachable mount on the new “Original Mauser” 98, introduced in 2017, simpler and more compact than the one offered two years earlier (previous page).

Aside from the obvious difference between an AR in .223 and a bolt-action .505 Gibbs, military tactics and hunting dangerous game, or going into the bush after a wounded animal, bear as much similarity to each other as the above-mentioned sniping and big-game hunting. Wind and scent are vital in big-game hunting, but are inconsequential in tactical situations. This is straying somewhat from the subject of this chapter, which is optics, but in hunting almost everything is interrelated. Tactical scopes and tactical rifles go together.

Before leaving the subject of hunting scopes, it is worth noting that anyone contemplating a hunt on horseback needs to pay attention to what will, or will not, fit in the standard saddle scabbard. Most of the scabbards provided by outfitters will not accommodate much more than a one-inch-tube, 3-9X scope, if that. However, even if you have a custom scabbard made to fit an oversized scope, most wranglers are likely to look at it askance. There is a limit to what you can comfortably fit on a horse, under his saddle leathers, and still have him tolerate you, much less like you. Your horse’s opinion may not matter to you now, but it will when he sees you coming and starts rolling his eyes and stomping. The alternative of slinging your oversized rifle on your back and riding that way may seem like a good idea at the base of the mountain on an open trail. It will be less appealing (and considerably more hazardous) when you get into the inevitable brushy tangles that occur along any trail, in any mountains.

* * *

If forced to choose one scope mount that has proven to be the best, under the widest range of situations and circumstances, it would be the standard Leupold split ring. Originally designed by Redfield (and commonly called Redfield rings and bases), it was adopted by Leupold and quickly squeezed out all of its own earlier designs, including the Adjusto mount and several others.

The Redfield/Leupold has a dovetail on the front ring, with locking screws on the rear base that allow windage adjustments if needed. There are all kinds of variations, including the “double-dovetail” that employs this immensely strong feature both front and back. The single dovetail allows the scope to be installed in the rings and moved on and off without disturbing them, while the double-dovetail requires the lower parts of the rings to be installed and aligned, and the scope installed afterwards. The double-dovetail is intended for hard-kicking rifles or to secure extra-heavy scopes.

Conetrol mounts are very good, but extremely finicky to install. The ring looks like one smooth, seamless piece of steel if installed correctly. I like Conetrol mounts very much, and had them on one or two rifles. A similar approach is the S&K mount, in which the rings really are one piece of steel. They are flexible and bend enough to be fitted on the scope tube, then pulled snug. They are locked into place with a set screw on each side of the base that tightens the ring like a clamp. They look elegant, and are guaranteed to bend in and out through three hundred or so installations without weakening. They allow installation of the scope low over the action, and have absolutely no projections to get in the way.

At the other end of the elegance scale is the Weaver mount. They are strong, cheap, easy to install, and downright ugly. That pretty much exhausts both their good and bad points.

Another manifestation of our current phase of military adoration is the increasing use of the Picatinny rail, a device designed at Picatinny Arsenal many years ago. It resembles the Weaver mount, except that instead of having two bases, it is one long base with multiple grooves its entire length. The Weaver ring locks onto its base by a cross screw that fits into that groove, preventing any unscheduled movement forward or back. With multiples grooves, the scope (or any other device you care to attach, like a flashlight) can be adjusted just by loosening the lock screws and repositioning it. Picatinny rails come in different lengths, and many tactical rifles are festooned with so many of them you’d think it was a fashion statement, like wearing camo to the beer store. I have nothing against a Picatinny rail on a military rifle, but I object to them on a hunting rifle, not just on the grounds of looks or utility, but because I have taken too much skin off too many knuckles, brushing them against the sharp corners of Picatinny rails. The standard Picatinny rail resembles a saw blade. There is no reason I can see why these sharp corners could not be beveled off and rendered less life-threatening, but no one seems to do it.

S&K mounts have no projections whatsoever, and can be as low and unobtrusive as the scope and bolt handle will allow. For elegance, they are unbeatable. The rifle is a Montana Rifle Co. ASR, in 7x57; the scope is a Leupold VX-III 1.75-6x32.

In the early heyday of custom rifles, Conetrol or Buehler mounts were used if something more upscale than the Redfield or Leupold was desired. In the 1990s, these began to be displaced by Talley mounts, to the point where Talleys became de rigueur on any rifle aspiring to elite status. Talleys are detachable mounts, with a lever on each ring that locks it into place, or allows the scope to be removed. Dave Talley’s spluttering denials notwithstanding, his mounts are both tricky to install, and possible to install in such a way that the scope is held tight to only one of the bases. I know this, because I’ve done it.

As a detachable mount on a dangerous-game rifle, I dislike them because removing the scope requires three separate movements (loosen one ring, loosen the other, rock scope off bases), whereas a properly fitted claw mount is so eumatic as to defy belief. You can do it entirely by feel, keeping your eye on the opening in the brush where you expect the buffalo to appear. With a claw, there is nothing to fall off, and nothing that needs tightening after removing the scope to keep it from falling off, unlike the Talley. On top of which, with their cross screws to connect the two halves of the rings on the top, Talleys are anything but elegant. How they became so popular is beyond me, unless it’s the fact that having a claw mount installed today is hideously expensive, as well as requiring gunsmithing skills that seem to be disappearing.

Talley mounts on a Schultz & Larsen Model 65DL, in .358 Norma.

There are other alternatives if a detachable mount is desired. Phil Pilkington, years ago, designed a system to convert the standard Redfield or Leupold. The left lock screw on the rear base is replaced by a lever that locks over the ring, but when rotated 180 degrees presents a flat surface, allowing the scope to be rotated out to the left and lifted out of the front dovetail. I had one of these on a .416 Weatherby and it worked fine. As long as the right lock screw is pinned so it can’t move and throw the windage off, the scope returns to zero.

In the early 1990s, Leupold got back into the detachable-mount game with their QD mounts. The rings had little posts that fit into the bases, and were locked or released by a small lever. Actually, by a too small lever. They were certainly short and unobtrusive, but under recoil they would tighten down (good, in theory) to the point where they could not be removed with simple thumb and finger pressure (bad, in practice). You needed either pliers or a little wrench, neither of which I normally carry hunting. I found this out the hard way, high on Mount Longido in the Rift Valley, hunting Cape buffalo. The rifle was a .458 Winchester belonging to a friend, and one shot was all it took to weld those levers in place. When the wounded buffalo came out after us, the scope was still clamped firmly in place, and I found myself shooting at anything black through the scope. The last shot was fired from the hip, at which point the scope had ceased to matter. Having come out of it alive, I decided not to tempt fate, and have never used Leupold QD mounts since.

European makers of scope mounts, such as EAW, Bock, and Recknagel, have come up with many different designs over the years. They still love detachable mounts, and have new designs for those as well as making countless variations on the venerable claw.

Much as I admire the claw, it has limitations. For example, in an earlier chapter I looked at my favorite dangerous-game rifle, which has a Swarovski 1.5X, on a 26mm straight steel tube, in claw mounts. Because it lifts from the rear, you are limited as to the size of the objective lens, with a straight tube really working best. Where there is a large objective but a smaller ocular bell, mounts have been made that release and rock upwards from the front. Others place the ring around the objective lens, which solves one problem but then forces the gunsmith either to mount the scope too far back, or with the front base out on the barrel.

Of all the different detachable systems I have seen, including at least two dozen variations on the claw, the one that gets my vote as the most eumatic, intuitive, and easy to use is the above-mentioned claw on my .450 Ackley. Not only can it be removed with one motion of one hand without looking down, you can replace it the same way by holding the scope with your finger beside the front claw, feeling for the base, and then snapping into place. This is possible with no other scope mount, to the best of my knowledge, and certainly, with no other detachable mount is the scope faster to remove or replace.

In case you are wondering, the expense with claw mounts is in fitting the bases. They are not merely screwed to the bridge and ring. Mine are both screwed and silver soldered. This soldering makes them practically part of the action, but it requires great skill and knowledge of how to use a heat sink, if you are to avoid compromising the hardness of the action. My old German gunmaker, Siegfried Trillus, could do this, and scoffed at those who said it was impossible. Would that Siegfried were still around, and that I could afford the cost of installing claws on a couple of other rifles at about $2,000 apiece.

Another drawback of claw mounts that really should be mentioned is that they pretty much limit you to having one particular scope on a rifle. However, if it is the right scope, I can live with that.

* * *

At various times, scope makers have included lens covers with their scopes, and after-market manufacturers have produced different types of covers, mostly to keep raindrops off lenses, but also to protect the scope from knocks and bangs.

In the 1980s, someone came up with the bright idea that if these covers were made of clear plastic, then you could see to shoot with the covers on. This sounds great, unless you have your scope mounted low with minimal clearance for the bolt handle, and the cover prevents the bolt from opening. That can be exciting after your first shot at a brown bear in pouring rain. One German scope maker who refused to do this explained that the plastic would prevent the shooter from enjoying the full benefits of his superb lenses. I suggested that heavy rain on the lenses would do the same thing, and with transparent covers you’d at least have a chance. He counter-argued that, if the rain was that heavy, then the drops would prevent you seeing through the plastic cover, no? With the development of water-repellant coatings, the problem is solved, at least regarding water. Scope covers also keep out dirt and prevent scratches. They are worthwhile having on even when it isn’t raining, so the see-through feature does have its merits.

Swarovski 1.5x20 Habicht Nova scope in claw mounts on a .450 Ackley. The scope can be removed easily, without looking, and replaced almost as easily.

Then there are the little spring-loaded flaps that fit on the scope front and back. They certainly provide a degree of protection, but it takes two motions to flip them up and I detest the look of them.

All of this is getting very arcane and nit-picky. My point is that some of these accoutrements, which may seem like a dynamite idea in the store, can seriously impair the usability of your rifle under certain conditions, and often in ways you never suspect until it actually comes to pass. A scope cover that prevents the bolt opening and closing is one example, and how many of us would take the time to practice with the cover on to find this out ahead of time? Or releasing those spring-mounted flaps within the (very sharp) hearing of a whitetail, to see how he reacts to the sound of that gentle twang?

* * *

In an article titled “The Ideal Big-Game Rifle,” which appeared in the Outdoor Life Guns & Shooting Yearbook in 1985, writer and big-game guide Bob Hagel observed that “A scope of no more than 4X, and as short and light as possible, is the best all-around big-game scope available. If you can’t see a big-game animal well enough to hit it with a good 4X hunting scope, that animal is sure as hell too far away for you to be shooting at it.”

A great deal has changed in the world of optics in the third of a century since Hagel wrote that, but I agreed with it then and I agree with it now. This is not to say that I don’t outfit many rifles with scopes of more than 4X, but the reason is that it is getting damned difficult to find a high-quality scope with those simple specs. The best-quality scopes available today are variables, with fixed-power models largely made using yesterday’s technology and costing as little as possible. There are exceptions, of course, but why move heaven and earth to find a high-quality fixed 4X when you can buy a perfectly good Leupold Vari-X III 2.5-8 for less money?

A modern package—the Ruger Model 77 Hawkeye FTW Hunter, in 6.5 Creedmoor, fitted with a Swarovski Z8i 1-8x24.

Most such scopes that I have fitted on my rifles are set at maximum for sighting in (the better to see the target, my dear), then moved to 4X or 5X for hunting. I do have a Leupold fixed 3X that I ordered from their custom shop to go on a .256 Winchester Magnum rifle, but I was being deliberately retro. Leupold also makes a neat little fixed 2X that is a straight one-inch tube, is eight inches long, and weighs about six ounces. It is so inexpensive, a serious rifleman should buy two or three, just to have around. In their catalog, Leupold says the scope was made at the insistence of its employees in Oregon, serious hunters all, who appreciate the virtues of such glass.

In various places, I have written that, were I condemned to use nothing but Leupold scopes for the rest of my hunting life, I would not feel disadvantaged. There is not much you need to do in hunting that cannot be done by one or another Leupold scopes. Their forté is the one-inch tube, and the hard fact is that for 90 percent of the hunting done by 90 percent of the big-game hunters in the world, a one-inch-tube scope is not only good enough, it is better than most.

They are universally lighter than a comparable 30mm tube scope, can be mounted lower, and are generally more compact and less clumsy. They give nothing away in terms of durability, being shock-, water-, fog-, and everything-else-proof. They may lag behind in light transmission, but this is less important for most American hunting than it is in Europe.

Swarovski, Zeiss, and Schmidt & Bender all make one-inch models. If you can find one, the Kahles one-inch scopes that were sold in the US for a while are superb, both in terms of optics and durability.

The current fashion, even among the average deer hunter, is a 30mm tube and high power—the higher the better. In a deer camp in Kansas a while back, there was a group from Ohio that included a couple of young kids. One went around to every table at dinner, telling all who would listen that his father had a rifle that could kill a deer out to a thousand yards. Never mind the fact that we were hunting from stands, and it was the wooded hills of east Kansas where there was not even a view longer than four hundred yards, he was ready, by golly! The guy I was with shot a buck at one hundred yards, while I shot a buck and a doe at 140 and 110 yards respectively. Only one hunter had a chance at more than three hundred yards, and he missed. What does that tell you?

The best buck, as I recall, was decked by a hunter in his seventies who was there with his fifty-year-old son. He was armed with a Savage 99 in .308 Winchester that had obviously been around, but was well looked after. It was topped with a Redfield 3-9X that had been on it since he bought it in the 1960s. The whole outfit added up to a slim, trim, practical hunting rifle. When the aforementioned kid came around to our table to tell us about his dad’s super-rifle, the old gentleman listened politely, nodded, and said, “Well, good luck to him.” It’s nice to spend time with courteous people.

And an ultra-traditional package: the Mannlicher-Schönauer 6.5x54 M-S, in the “African” model produced by both Mauser and Steyr in the 1920s. At one time, this rifle was fitted with a claw mount, since replaced by a Leupold “Adjusto” mount and a Leupold FX-II 2.5x20 scope. The rifle has an old-fashioned, elegant look to it, and is a very efficient hunting rifle out to 250 yards—easy to shoot, accurate, and smooth as glass.

A variety of rifle slings, old and new, European and American. Some are more decorative than others, but all fulfill the most basic requirement of making it easier to carry the rifle while not getting in the way.