4

THE SHAPE OF THE GOSPEL

(Or, The Tacit Trinitarianism of Evangelical Salvation)

But when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave, but a son, and if a son, then an heir through God.

GALATIANS 4:4–7

When God designed the great and glorious work of recovering fallen man, and the saving of sinners, to the praise of the glory of his grace, he appointed, in his infinite wisdom, two great means thereof: The one was the giving his Son for them, and the other was the giving his Spirit to them. And hereby was way made for the manifestation of the glory of the whole blessed Trinity; which is the utmost end of all the works of God.

JOHN OWEN1

Now that we have seen the gospel as God-sized, we are ready to see that the Trinity has also given a particular threefold shape to the gospel. In this chapter, we will look at the gospel as something that has had this threefold shape impressed on it by the triune God. Speaking about “the shape of the gospel” is, of course, speaking metaphorically. Literally, it is physical objects that have shapes, contours, edges, and corners. The metaphor of “shape” can help us perceive the metaphorical contours, edges, and corners of the gospel. But shape is only metaphor, and it is high time we spoke as un-metaphorically as possible about the thing itself. The thing itself is the economy of salvation.

THE ECONOMY OF SALVATION

The economy of salvation is the flawlessly designed way God administers his gracious self-giving. When God gives himself to be the salvation of his people, there is nothing haphazard or random about it. God’s agape is never sloppy. He has a plan, and he follows a procedure that is perfectly proportioned. Theologians call this well-ordered plan the economy of salvation.

The word economy can be an awkward one to use because in contemporary English it has come to sound like a word about money and markets. When we hear about economics, we think of the social science that studies the distribution of goods and services in human societies. An economy would be what an economist studies. But the word economy is much older than the (relatively young) science of economics. It comes from an ancient Greek compound word, oikonomos, made up of the words oikos (house) and nomos (law). An economy is the law that provides for orderly management of a household. The sense of the word may be better brought out by recalling the term “home economics,” which makes explicit the reference to a home and suggests that the home economist is paying close attention to how all business is conducted for the good of the household. The word economy contains the far-reaching idea of the orderly arrangement of a shared life, which is a much broader concept than the modern science of money. Theology has retained the word in its older, wider sense, following the usage of ancient Greek writers like Aristotle, for whom an oikonomos was an administrator or steward over all a household’s residents and property. It would be a useful word to reclaim just on these grounds.

Above all, though, economy is a word worth learning because it is an important word used in Scripture itself. Since it is usually obscured by readable English translations, it takes a little work to tease it out and bring it to our attention. We have already seen the single most important occurrences of the word in the New Testament. In our study of the first chapter of Ephesians above, we translated Ephesians 1:10 as saying that God made known the mystery of his will “through an economy in which, when the times were fulfilled, he would sum up everything . . . under one heading: Christ!” There we went out of our way to preserve and highlight the word oikonomia, but at the cost of a rather poorly flowing English sentence. Better translators have made smoother sentences from it. The following translations are all responsible renderings of Paul’s Greek sentences, but watch the transformation that the word oikonomia is put through in each of them:

That in the dispensation of the fulness of times he might gather together in one all things in Christ. (kjv)

. . . with a view to an administration suitable to the fullness of the times, that is, the summing up of all things in Christ. (nasb)

. . . which he purposed in Christ, to be put into effect when the times will have reached their fulfillment—to bring all things . . . together under one head, even Christ. (niv)

. . . his purpose, which he set forth in Christ as a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in him. (esv)

And this is the plan: At the right time he will bring everything together under the authority of Christ. (nlt)

The first two translations give us strong and attention-getting nouns as translations for oikonomia: a “dispensation” and an “administration.” The KJV’s “dispensation” is based on the fact that the Latin word for oikonomia is dispensatio. The NASB’s “administration” may have unfortunate bureaucratic connotations and introduces so many syllables that it loses readability points, but it has the virtue of showing us that there is a long, solid noun here in the text, to pay attention to and ask questions about. The NIV hides the word behind the verb phrase “to be put into effect.” The ESV manages a smooth reading by shrinking oikonomia to the less massive “plan,” and the NLT puts that word in a phrase that emphasizes it: “This is the plan.”

The economy of salvation is not a ramshackle affair but a perfectly ordered domestic space. It is not a tumbledown shack but a manicured estate. In Ephesians, Paul plays on this “household” metaphor repeatedly: The economy (house-law, 1:10) is God’s household (2:19) in which the Father (from whom all fatherhood is named, 3:15) builds us up together (2:20–22), we formerly homeless outcasts (2:19), to make us a dwelling of God by the Spirit (2:22).2

When Paul talks about God’s economy, his point is that God is a supremely wise administrator who has arranged the elements of his plan with great care.3 To watch God carry out this economy is to be instructed in the mystery of his will and to gain insight into the eternal purpose of his divine wisdom. Even those angelic beings, the “rulers and authorities in the heavenly places,” are instructed in this “manifold wisdom of God” as they see it worked out now in God’s household management of the church (3:10). Paul’s own ministry, he says in 3:9, is “to bring to light for everyone what is the plan [oikonomia] of the mystery hidden for ages in God who created all things.” What is made known in this economy is something “which was not made known to the sons of men in other generations as it has now been revealed to his holy apostles and prophets by the Spirit” (3:5). The instruction that men and angels receive is from coming to understand how God has arranged the elements of his plan. We can understand the eternal purpose of God, framed in his unfathomable wisdom, by paying close attention to this economy of salvation.

WHERE GOD EXPRESSES HIMSELF

There is a reason why we have so much to learn from attending to the economy of salvation. The reason is that God has carried out the central events of this economy with the definite intention of making himself known in them. The economy of salvation teaches us things because God intends it to. Specifically, God’s intention is for the economy of salvation to teach us who he is. This is where the one true God identifies himself and reveals something ultimately definitive about who he is. Ephesians emphasizes the revelatory character of God’s economy. We learn the character of God’s wisdom by studying his ways in the administration of the unfolding history of salvation. We attend to his craftsmanship. We look for the marks of his workmanship to see what decisions he has made. In those decisions, we see God’s self-revelation. It is in the central events of this economy that God has actively and intentionally expressed his character and identified himself. We are not merely saying that God, being by nature a great craftsman, leaves signs of his personal style of workmanship on everything he does and so has left marks of self-expression on the economy of salvation. No, when it comes to the great, defining events of the economy of salvation, it has been God’s direct intention to do these things in order to make himself known to us.

In the old covenant, the central events were the choosing of Abraham, the exodus from Egypt, and the gift of the Promised Land. In these events God was doing something in history that brought about knowledge of him. “I will take you to be my people, and I will be your God,” he declares in Exodus 6:7, with the result that “you shall know that I am the Lord your God, who has brought you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians.” At the other end of Old Testament history, the Lord promises that he will bring his people back from exile and that this mighty act will result in sure knowledge of his identity and character: “And I will put my Spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you in your own land. Then you shall know that I am the Lord; I have spoken, and I will do it, declares the Lord” (Ezek. 37:14). Over and over, God links accurate knowledge of his character to recognition of a definite constellation of his mighty acts on behalf of his people.

But those old-covenant events all cry out for their divinely ordained fulfillment in the new covenant, where God completes his intention to make himself known. The book of Hebrews begins by announcing this breakthrough to a new level of God’s self-expression toward us: “Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son” (Heb. 1:1–2). This Son is not simply a messenger who carries God’s words, or an interpreter who explains God’s ways. He is “the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature” (v. 3), and his being sent into the world is itself a mighty act of God to simultaneously save us and reveal himself. Together with its necessary completion in the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, the advent of the Son of God is the central event in which God has made himself known: “He has spoken to us by his Son.”

A parable from contemporary life may clarify the way God makes himself known in the economy of salvation. Like all parables, it throws light on a particular truth, but its illustrative helpfulness should not be pushed beyond the bounds of common sense. With that warning in place, here is the parable. A woman works for a business that provides her with a spacious cubicle office. The office includes everything she needs to get her job done. The computer, desk, chairs, conference table, filing cabinets, and bookshelves are all arranged to conduct the company’s business professionally. There is framed art on the one fixed wall of the office and an area rug that really ties the whole room together. But the art and the rug both came to her through the company’s central warehouse and were chosen by a purchasing committee to communicate the company’s professional image. She has added a few touches to the cubicle that express her personality: two family photos beside her computer, a framed motto on the wall, and some knickknacks on a shelf. But one day she makes a new friend at the office and says to her, “You can’t tell anything about who I am from this cubicle. Come to my home, and you will understand me.” There, everything the friend sees is an expression of her personality. She bought that house because it suited her, and every furnishing in it is her choice and arrangement. To see her in her own domestic space is to know something about who she is, not just how she conducts company business. Her oikonomia is a self-expression in a way her professional space is not.

The analogy could be tweaked to make it more appropriate. We could say, for instance, that in the case of God, the happy land of the eternal Trinity is God’s actual home, while the economy of salvation is his home away from home or the home he makes hospitably among his creatures. We could even call the immanent Trinity God’s “family of origin.” And we could add that, setting aside our wordplay with the term oikonomia (house-law), God’s location for self-expression and revelation is not a living room or a location at all, but a series of events. But by the time we have made these changes, we have started turning the analogy into the reality. The reality is that the economy of salvation is God’s intentionally communicative domestic arrangement, which he administers specifically to communicate his character and identity.

The economy of salvation has a meaningful form. If it were only the series of events that God undertook to save us, the economy might conceivably be a long, spread-out sequence of events, all with equal importance. But the economy also communicates. God has given form and order to the history of salvation because he intends not only to save us through it but also to reveal himself through it. The economy is shaped by God’s intention to communicate his identity and character. If the history of salvation is also the way God shows us who he is and what he is like, then it makes sense that it would be a history with a clear and distinct shape. It may be vast, but it is well proportioned and does not suffer from sprawl. It features an obvious central point as the focus of attention. That obvious central point is the sending of Jesus, the Son of God anointed by the Holy Spirit. So even though the economy of salvation starts in the garden of Eden, spans hundreds of divine interventions, and is not concluded yet, it is still easy to discern its center and to read its total form. The center of the economy of salvation is the nexus where the Son and the Holy Spirit are sent by the Father to accomplish reconciliation.

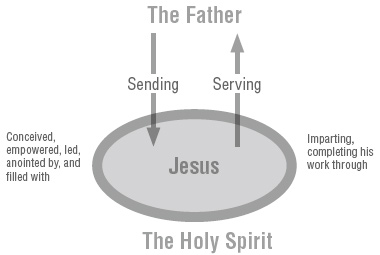

WATCH JESUS AND THINK TRINITY

It might seem odd to point anywhere but to Jesus Christ as the center of the history of salvation. He is indeed, in person, the very center of the divine plan, and in fact we are not pointing elsewhere than to him for the revelation of God. But our goal is not just to put our finger on the center but to point to it in such a way that the total form of the economy also becomes apparent. To get that big picture, we have to see Jesus not in isolation but in Trinitarian perspective. He is sent by the Father, and everything he does is done in company with the Holy Spirit.

First, Jesus is sent by the Father. By his own testimony, everything Jesus does is the work of the Father. He does not act on his own initiative, and he is not carrying out his own plan. “I have come down from heaven, not to do my own will but the will of him who sent me” (John 6:38). He walks among us as the one who comes from the Father to reconcile us with the Father. There is no way of understanding the work of Jesus without taking the Father into account. To think about Jesus in isolation from the Father is to ignore Jesus’ self-understanding: he is from the Father. His fellowship with the Father was the secret that sustained him and gave him his reason for living: “My food is to do the will of him who sent me and to accomplish his work” (John 4:34). If you have missed this aspect of what God is saying through the New Testament, I recommend speed-reading the Gospel of John and asking yourself what your dominant impression about Jesus is. It is bound to be his relationship with the Holy Father who sent him and is with him. As the nineteenth-century Anglican bishop Handley C. G. Moule summarized, “Nothing shines more radiantly in the New Testament than the eternal love of the Father for the Son.”4

Second, Jesus works in company with the Holy Spirit. The cooperation of the Son and the Holy Spirit in the economy of salvation is an even richer subject for study, if possible, than the cooperation of the Father and the Son, because it expands our view of the scope of God’s plan. When we look from Jesus to the Father, we see a great depth: the ultimate source, power, and purpose of the mission of Jesus. But when we look from Jesus to the Holy Spirit, we see a great breadth: the magnificent complexity and completeness of the economy. This scope becomes visible because of the way the Holy Spirit surrounds the ministry of Jesus on all sides. The work of the Spirit precedes the ministry of Jesus in that the Spirit is the one who brings about the virgin conception, the incarnation, and the forming and setting apart of Christ’s human nature (Matt. 1:20; Luke 1:35). Lest we overlook the Holy Spirit’s role at the beginning of Christ’s earthly life, the ancient Apostles’ Creed picks it out as one of the few things it mentions prior to the crucifixion: “conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate.” Here the creed has good insight into the Gospels, which are silent about the Spirit’s role in Christ’s ministry for chapters on end but set the stage with a cluster of references to the Spirit at the beginning of the story of Jesus. This is obvious in Matthew and Luke with their accounts of the virgin conception, but even Mark’s Gospel, which neither narrates the virgin conception nor mentions the Holy Spirit often, begins with a cluster of Spirit references (1:8, 10, 12).5 The story of Jesus starts with the Holy Spirit.

His life and ministry also continue in the power of the Holy Spirit. Simply reviewing the biblical statements on this subject is powerful. R. A. Torrey’s summary of Christian doctrine, What the Bible Teaches, gathers up the lines of biblical evidence helpfully:

1) Jesus Christ was begotten of the Holy Spirit. (Luke 1:35)

2) Jesus Christ led a holy, spotless life, and offered Himself to God, through the working of the Holy Spirit. (Hebrews 9:14)

3) Jesus Christ was anointed for service by the Holy Spirit. (Acts 10:38; Isaiah 61:1; Luke 4:14, 18)

4) Jesus Christ was led by the Holy Spirit in His movements. (Luke 1:4)

5) Jesus Christ was taught by the Spirit who rested upon Him.The Spirit of God was the source of His wisdom in the days of His flesh. (Isaiah 11:2; compare Matthew 12:17, 18)

6) The Holy Spirit abode upon Him in fullness and the words He spoke were the words of God. (John 3:34)

7) Jesus Christ gave commandments to His apostles whom he had chosen, through the Holy Spirit. (Acts 1:2)

8) Jesus Christ wrought His miracles in the power of the Holy Spirit. (Matthew 12:28; compare 1 Corinthians 12:9–10)

9) Jesus Christ was raised from the dead by the power of the Holy Spirit. (Romans 8:11)6

The Holy Spirit is also involved in the carrying out of Christ’s work after his death, resurrection, and ascension into heaven. It is through the Holy Spirit that the work of Christ is applied to believers so that they are born again, become temples of God, and are empowered for discipleship. When Christ ascended into heaven, he sent the Holy Spirit to minister God’s presence among his people. Indeed, when the Holy Spirit is poured out on Pentecost, his personal presence in salvation history after the finished work of Christ inaugurates a new era in God’s ways with the world. Thus the work of the Holy Spirit surrounds the work of Jesus Christ, as he goes before and after the incarnate Son like a set of holy parentheses embracing the story of salvation in Christ.

The encouragement to watch Jesus and think Trinity can change the way we read Scripture and enable us to see things there that we may have overlooked before. When we turn our eyes upon Jesus and learn the habit of asking how the Father and the Holy Spirit are co-present with him, we can see that many of the most beloved biblical stories from the life of Jesus Christ have a Trinitarian background we had never noticed. Perhaps their presence is impossible to ignore at Christ’s baptism in the Jordan, when the Spirit descends in the form of a dove and the Father speaks from heaven: “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased.” But the baptism story should give us the interpretive key to the rest of the New Testament as well, because the Holy Spirit’s anointing power is always on the incarnate Son, and the Father’s good pleasure in his beloved is the secret of everything Christ does. We should always inquire after the hidden presence of the Spirit and the Father in the unhidden work of Jesus.

Attending to the Father’s presence in the life of Christ makes us look up higher than we are used to. Attending to the Spirit’s presence in the life of Christ makes us look back and forth further than we are used to. Taken together, the presence of the Father and the Spirit makes it clear how the life of Jesus is the focal point of the economy of salvation.

Seeing Jesus in the center of these divine actions is crucial for coming to understand the shape of the economy of salvation.

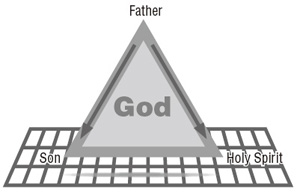

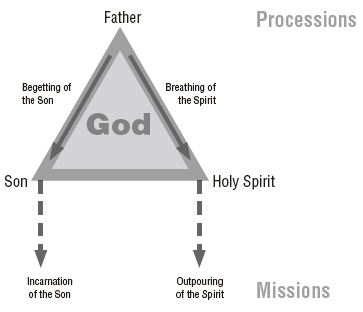

THE TWO HANDS OF THE FATHER

So far we have approached the economy of salvation from an intentionally Jesus-centered point of view. We started here on purpose, because the best way to come to understand the Trinity is to begin with the clarity and concreteness of Jesus the Son, sent by the Father in the power of the Spirit.7 But once we have learned to perceive the Trinity at work in the life of Christ, there is another, complementary way of viewing the economy that can expand our vision even farther. That way is to turn our attention from Christ as the center of salvation toward the Father as the source of it. The Father is the one who sends Christ on his mission of salvation and also sends the Holy Spirit to complete the work. Viewed from this angle, the economy of salvation is something that has been molded into shape by the Father himself, through his two personal emissaries, the Son and the Spirit.

One of the greatest theologians of the early church, Irenaeus of Lyons (who wrote around the year 200), used a striking metaphor for this Father-centered view of things. He noticed that in the story of the creation of man in Genesis 2:7, “the Lord God formed the man of dust from the ground.” Irenaeus noted God’s direct, personal involvement in the making of man’s body and soul. Against false teachers who preferred that God would have delegated to angels the dirty work of making the human body, Irenaeus insisted that God the Father did it himself, with his own two hands:

It was not angels, therefore, who made us, nor who formed us, neither had angels power to make an image of God, nor any one else, except the Word of the Lord. . . . For God did not stand in need of these . . . as if He did not possess His own hands. For with Him were always present the Word and Wisdom, the Son and the Spirit, by whom and in whom, freely and spontaneously, He made all things,to whom also He speaks,saying,“Let Us make man after Our image and likeness.”8

Of course Irenaeus did not mean that the Son and the Spirit were literally God’s hands. In fact it is almost impossible to take the “twohands” image literally, because to do so would be to reduce the Son and the Spirit to appendages of the Father. Irenaeus’s point was that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are the one God who created man. But the image he suggests poetically, of the Father making man with his own two hands who are the Son and the Spirit, rivets our attention on God the Father as the source of all things, even as all things are worked out through the Son and the Spirit.

What this second-century theologian said about creation can help us in our goal of seeing the form of the entire economy of salvation. God did not leave the economy of salvation to take on its own shape, nor did he delegate its craftsmanship. The Father formed it himself with his own two hands. He was never without those two hands, the eternal Son and the eternal Spirit. And in the fullness of time he sent them on their missions into the world to bring us to himself. The economy of salvation, then, takes on its effective and meaningful shape when the Father sends the Son to be incarnate and the Spirit to be poured out (see Diagram 4.2).

The Son and the Spirit are always together in carrying out the work of the Father. They are always at work in an integrated, mutually reinforcing way, fulfilling the Father’s will in unison. Yet they are not interchangeable with each other, and they are not duplicating each other’s work. In fact, the Son and the Spirit behave very distinctively in carrying out the concerted work of salvation. The Son is the Son and acts like the Son, while the Spirit is the Spirit and acts like the Spirit. Understanding them as the Father’s two hands helps us see their unity (they both come from the Father for one purpose) and their distinctness (there are two hands, not one). God the Father did not send two emissaries who would do the same work twice. Because the Son and the Spirit are distinct, there is nothing redundant or even repetitive about their twofold work. We could describe their differences by saying the Son and the Spirit have distinct personalities, or that their personal styles show through in the way they carry out their distinct tasks. When we see their distinctness, we see the scope of the economy, which is where God reveals himself. Ninety percent of Trinitarian theology happens right here, where we come to understand the unity and distinction of the work of the Son and the Spirit, sent by the Father. Our task is to learn how to recognize this unity in distinction as revealed in the Bible and to describe it in a helpful, clarifying way.

The first clue to our task is obvious: the Son of God became incarnate and died for us, but the Holy Spirit did not. The Father sent the Son to take up the great work of incarnation and propitiation, while he sent the Holy Spirit to make that work possible in the first place (as we saw above, through the virginal conception and the anointing of the man Jesus Christ), and then to realize and complete the work after Christ had accomplished it. From this vantage point, we can perceive the distinctive profiles of the Father’s two emissaries. Starting from here, we can even derive two entirely different vocabularies for the work of the Son and the work of the Spirit.9 Push their unity and cooperation to the back of your mind for a moment while we examine their distinctness.

The Son and the Spirit are both ways that God keeps his promise to be “God With Us.” But the Son is God With Us in the direct, personal sense that he is the eternal Son in human nature. The Spirit, on the other hand, is God With Us as the eternal Spirit dwelling among us as in a temple. The Son is God With Us by becoming one of us, but the Spirit is God With Us by living among us.

Think of the key words that are associated with the work of the Son and the Spirit. The right word for the Son’s work is incarnation but for the Spirit it is indwelling. The Son becomes enfleshed, but the Spirit lives within. The Son of God took human nature to himself, personally taking on everything it means to be fully human. He was a divine person who had always had a divine nature, and without ceasing to be that eternal person with the divine nature he added to himself a complete human nature. So the incarnate Son became a human person in this particular sense: he was the eternal divine person who took on human nature. Incarnational theology is a deep subject and is too complex to explore in detail here. But the classic term used in that doctrine is hypostatic union, which means that Jesus was one person who possessed both God’s nature and man’s nature. The Son became human. The Holy Spirit, on the other hand, did not take human nature into personal union with himself. He did not become human. Instead, he indwells people.

The contrast becomes even clearer if you consider switching the categories between Son and Spirit. What if we said that the Son of God indwelled Jesus Christ instead of saying that he became Jesus Christ? That would be an entirely inadequate christology. It would make Jesus a human person filled with the Holy Spirit rather than the incarnate Son of God. Or what if we said that when the Holy Spirit comes to us, he becomes incarnate in us and takes on our nature? Again, that would be a severe misunderstanding of the Spirit’s work and would lead to confusion about everything in the life of a Christian. Incarnation is not indwelling, but we need both if we are to experience God With Us.

When we look to the atonement, we also see the need for different vocabularies for the Son and the Spirit. Obviously the Spirit did not die for our sins, but there are less obvious implications of this fact. The work that Jesus Christ does for us is a vicarious, substitutionary work: he steps into the place that we occupy and offers himself to God in our place. As a propitiation for sin, the incarnate Son replaces us and bears the wrath of God on our behalf. The Spirit, on the other hand, does not substitute for us but empowers us. He does not take our place but puts us in our place. And in carrying out the great work of atonement, the Son completes the work once and for all in his death and resurrection, but the Holy Spirit takes that completed work and applies it to individual people.

Over and over in our Christian experience we note the difference between the Son and the Spirit. There are many things we say about the Son of God that we would never say about the Spirit. We are to be conformed to the image of the Son (Rom. 8:29), not the Spirit. We are told to be like Christ, and even to imitate God the Father in a certain sense (Eph. 5:1), but never to imitate the Holy Spirit. Again, there is one mediator between God and men (1 Tim. 2:5), and that is the man Jesus Christ, not the Holy Spirit. It may be tempting to extend these terms (conformed, imitate, mediator) to the Holy Spirit, from a sense of wanting to defend the full equality of the Spirit or to make sure the third person has the same honor as the first and second. We might even be able to argue that there is some metaphorical sense in which we imitate the Spirit or to extend the word mediation to describe the way the Spirit brings us to God through Christ. But that would be to speak very loosely and to ignore the categories that Scripture establishes. We would be in danger of missing the Spirit’s distinctive work by confusing his work with Christ’s. The best way to keep them unified is to see their difference; we distinguish in order to unite.

Chart 4.1: The Work of the Son and the Spirit

| The Work of the Son | The Work of the Spirit |

|---|---|

| God with us, as one of us | God with us, dwelling among us |

| Incarnation | Indwelling |

| Hypostatic union | Communion |

| Assumes a human nature | Enlivens human persons |

| Substitutes for you | Regenerates you |

| Takes your place | Puts you in your place |

| Completes work all at once | Continues work constantly |

| Becomes a pattern for imitation | Forms us to fit that pattern |

| Is the one mediator | Unites us to the mediator |

| Accomplishes redemption | Applies redemption |

ACCOMPLISHED BY THE SON, APPLIED BY THE SPIRIT

A classic way of looking at the two-handedness of God’s work in salvation is the relationship between how the Trinity accomplishes redemption and how the Trinity applies that redemption to us. This idea of redemption accomplished and applied is a handy way of considering salvation in its objective and subjective aspects, even when the two phases of God’s saving work are not correlated with the Son and the Spirit.10 Redemption would not reach its goal without being applied, but there would be nothing to apply if it were not already accomplished. But recognizing the Son and the Spirit, respectively, as the leading figures in the two phases enriches the idea even more. Christ the Son accomplishes redemption in his own (Spirit-created and Spirit-filled) work. The Holy Spirit applies that finished redemption to us in his own (Son-directed and Son-forming) work. The two works are held together by an inherent unity. The Son and the Spirit are both at work in both phases; nevertheless, the Son takes the lead in accomplishment, and the Spirit takes the lead in application.

Where can we turn for evangelical witnesses to this truth? We could turn to John Wesley, who drew a clarifying line between “what God does for us through his Son” and “what he works in us by his Spirit.”11 Or we could turn to John Owen, whose work On Communion with God the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost was an elaborate exploration of related themes.12 Owen’s influence extends down to J. I. Packer, who lists this as one of his five foundation principles in Knowing God:

God is triune; there are within the Godhead three persons, the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost; and the work of salvation is one in which all three act together, the Father purposing redemption, the Son securing it and the Spirit applying it.13

But one of the most helpful teachers on this subject is Puritan John Flavel (1627–1691). He was so committed to clear teaching on the subject that he wrote two different books. In the first book, The Fountain of Life, he described how God the Father made provision for salvation and then accomplished it in Christ. In the second book, The Method of Grace, he provided a full treatment of the way salvation actually takes hold of a human life. The first book is grace accomplished; the second book is grace applied. Many theologians have organized their teaching on salvation around this distinction, but Flavel stands out from the rest because of the Trinitarian character of his teaching. His book on the accomplishment of salvation is primarily focused on what the Son has done, while his book on the application of salvation is primarily focused on what the Spirit does. His Fountain and Method books are Jesus Christ and Holy Spirit books, respectively. That is, the first book describes the “grace provided and accomplished by Jesus Christ,” while the second “contains the method of grace in the application of the great redemption to the souls of men” by the Holy Spirit.14

Flavel sees salvation worked out objectively in Christ, as God the Father loves the world and gives his Son (John 3); as he does not spare his Son and is therefore willing to give everything (Romans 8); as God is in Christ reconciling the world to himself (2 Corinthians 5). Nothing needs to be added to this complete salvation provided in the life, death, and resurrection of Christ. But it must be applied to each person who is to receive its benefits personally. And that application must also be a divine work, a work of the risen Lord who is not dead or done away with but is at the right hand of the Father. “From thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead,” and in the meantime, from thence he has sent the Holy Spirit.

Flavel is not trying to play the persons of the Trinity off against each other. He knows that the entire Trinity is at work in every aspect of salvation.15 But he also wanted to distinguish between the work in which the Son is the primary agent and the work in which the Spirit is the primary agent. He wants to distinguish more clearly between them precisely so he can unite them more firmly. In one sense, God the Father applies salvation to believers in Christ himself, giving the incarnate Son, in his vicarious humanity, a complete salvation that is applied to “Christ as our surety” and “virtually to us in him.”16 God blesses the man Christ with the fullness of all blessings of salvation, and it overflows to us. This substitionary application, however, is actually effective in the divine-human person of Christ himself, but only “virtually to us.” The actual (not merely virtual) application to us is “the act of the Holy Spirit, personally and actually applying it to us in the work of conversion.” This is the method of grace: the Father acts toward Christ, the Spirit acts from Christ.

Flavel is insistent that the application of redemption by the Holy Spirit is mandatory, not merely optional. Without it, the work of the Father and the Son is of no avail:

The same hand that prepared it, must also apply it, or else we perish, notwithstanding all that the Father has done in contriving, and appointing, and all that the Son has done in executing, and accomplishing the design thus far. And this actual application is the work of the Spirit, by a singular appropriation.17

and again:

Such is the importance of the personal application of Christ to us by the Spirit, that whatsoever the Father has done in the contrivance, or the Son has done in the accomplishment of our redemption,is all unavailable and ineffectual to our salvation without this.18

The reason God’s work waits on the fulfillment of the Spirit is that the Spirit is God. It would be insulting to say that “all that the Father has done . . . and all that the Son has done” is ineffectual until completed by some outside force. Flavel’s point is that the Spirit is not some outside force, but a force internal to the being of God, of the same substance as God the Father and God the Son. Flavel pounds the point home:

It is confessedly true, that God’s good pleasure appointing us from eternity to salvation, is, in its kind, a most full and sufficient impulsive cause of our salvation, and every way able (for so much as it is concerned) to produce its effect. And Christ’s humiliation and sufferings are a most complete and sufficient meritorious cause of our salvation, to which nothing can be added to make it more apt, and able to procure our salvation, than it already is: yet neither the one nor the other can actually save any soul, without the Spirit’s application of Christ to it.The Father has elected,and the Son has redeemed; but until the Spirit (who is the last cause) has wrought his part also, we cannot be saved. For he comes in the Father’s and in the Son’s name and authority, to complete the work of our salvation, by bringing all the fruits of election and redemption home to our souls in this work of effectual vocation.19

With the Spirit’s work in our lives, then, the Trinitarian circuit is completed: the Spirit accomplishes our union with Christ, hides our life with Christ in God, and makes Christ become “unto us wisdom, and righteousness, and sanctification, and redemption” (1 Cor. 1:30 kjv). This is the Trinitarian method of grace whereby God brings us to himself by being himself toward us.

Is this Trinitarian understanding of grace still active in evangelicalism in more recent years? Flavel was a well-catechized, Oxford-educated Presbyterian with rather precise convictions of the Puritan Reformed type. We would expect him to have careful doctrinal distinctions at hand. But how has the Trinitarian method of grace fared in the hands of later evangelicals? Flavel’s understanding of the Trinity in salvation was still alive and well in the nineteenth century in the theology of mass evangelist Dwight L. Moody. Moody presents a striking contrast to Flavel: his formal education probably did not extend beyond the fifth grade, he spoke to large audiences in simple terms, and his message tended toward the Arminian side of the evangelical spectrum. But we can tell that Moody’s brand of evangelicalism presupposed a Trinitarian gospel as much as Flavel’s did, because on a few occasions he made his underlying beliefs explicit. When he wanted to be more robustly theological, Moody had an interesting strategy: he would call a better-educated pastor to the platform with him and then interrogate him publicly on the subject at hand. One of his favorite interlocutors for these “Gospel Dialogues” was Marcus Rainsford (1820–1897), who was known “for his firm grasp of essential evangelical doctrine and for his peculiarly strong hold on the great foundation realities connected with the believer’s standing in Christ.” Moody valued Rainsford “for his clear cut definitions of doctrine and for his lucid and convincing statements of spiritual truth.”20

In one of these Gospel Dialogues, Moody said to the audience, “I have tried to put the truth before you in every way I could think of. Now I want to put a few questions to Mr. Rainsford that relate to the difficulties that some of you have.”21 Whatever those difficulties may have been, Rainsford quickly laid out a distinction between Christ’s work for us and the Spirit’s work in us:

Mr. Rainsford: Christ’s work for me is the payment of my debt; the giving me a place in my Father’s home, the place of sonship in my Father’s family.The Holy Spirit’s work in me is to make me fit for His company.

Mr. Moody: You distinguish, then, between the work of the Father, the work of the Son, and the work of the Holy Ghost?

Mr. Rainsford: Thanks be to God, I have them all, and I want them all—Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. I read that my Heavenly Father took my sins and laid them on Christ; “The Lord hath laid on Him the iniquity of us all.” No one else had a right to touch them. Then I want the Son, who “His own self bare my sins in His own body on the tree.” And I want the Holy Ghost: I should know nothing about this great salvation and care nothing for it if the Holy Ghost had not come and told me the story, and given me grace to believe it.22

Shortly after this interaction, Moody asked Rainsford what the result would be if somebody received the word of God that very night. Rainsford replied, “The Father and the Son will make their abode with him; and he will be the temple of the Holy Ghost. Where he goes the whole Trinity goes; and all the promises are his.”23

When the message of Trinitarian grace is simplified from the bulky tomes of a Flavel or an Owen to the Gospel Dialogues between a Moody and a Rainsford, is anything lost in the translation? The main points, I think, carry over quite well. Rainsford distinguishes Son and Spirit in order to unite them (“Thanks be to God, I have them all”), and in the process he uses Trinitarian categories to expand our view of the comprehensiveness of God’s work. There is, however, one element of the message that is in danger of being forgotten: the distinction between the work of the Son and the Spirit belongs to a realm higher than our own personal experience.

Moody was an evangelistic genius whose campaigns spoke to the immediate experience of his audiences. But when we say that the Son accomplishes redemption and the Spirit applies it, we are first of all speaking about the economy of salvation and only subsequently about our own experience. If we forget this, then our thoughts can get tangled up in all sorts of merely experiential distinctions, like the distinction between objective fact and subjective appropriation, or between truth in general and truth “for me.” Those distinctions lead to theological pseudo-problems if we try to use them in understanding the Trinitarian method of grace, and as a consequence, we think either of the Son’s work as insufficient or the Spirit’s work as an add-on. But the distinction between the work of the Son and the work of the Spirit is built into the Christian message. It is a distinction internal to the gospel itself, because it is internal to God himself. To rehearse it from the top: God in himself is Father, Son, and Spirit; so in the economy of salvation the Father sends the Son and the Spirit; so in our experience the Father accomplishes salvation for us in the Son and applies it to us in the Spirit.

Remembering that the only way to see the shape of the gospel is to see the shape of the economy of salvation, we can be grateful for thinkers like John Owen who wrote with such a comprehensive grasp of the economy. Calling the work of the Spirit “the second great head” of all the “gospels truths,” Owen pointed out how closely related it is to the sending of the Son. The Father gives the Son “for us,” that is, as a sacrifice for propitiation. But the same Father gives the Spirit “to us,” that is, as an indwelling presence. Together, these two sendings manifest God’s glory:

When God designed the great and glorious work of recovering fallen man, and the saving of sinners, to the praise of the glory of his grace, he appointed, in his infinite wisdom, two great means thereof: The one was the giving his Son for them, and the other was the giving his Spirit to them.And hereby was way made for the manifestation of the glory of the whole blessedTrinity; which is the utmost end of all the works of God.24

Some theologians, noticing the distinctiveness of the Spirit’s work in application of Christ’s work, have gone so far as to talk about two economies, one of the Son and the other of the Spirit.25 We stay closer to the storyline of Scripture, however, if we talk about the one economy of God and then go on to highlight its twofold character. God’s work, in other words, is not two economies, but one twofold economy. This may seem like a minor difference in terminology, but it helps us account for why the two phases of salvation overlap so much. The Spirit, for example, is already active in the accomplishing of salvation in numerous ways: he brings about the incarnation by causing Jesus’ conception, he empowers Jesus in his work, and he is the medium through which Jesus makes an offering of himself to the Father. Since the very name “Christ” implies “Son of David anointed by the Spirit,” it is apparent that without the Spirit there could be no Christ to accomplish salvation. So the Spirit is active in accomplishing redemption, but he acts by equipping the Son to do the work.

Similarly, knowing that we are looking at a single, twofold economy of God helps us recognize that the Son is still involved in the application of redemption in numerous ways. He is the risen and ascended one who sends the Spirit, and it is through the personal presence of the Spirit that Jesus himself also lives in the hearts of believers. So the Son is active in applying redemption, but he acts by equipping the Spirit to do the application. They are always mutually implicated, though in each phase one of them sets the other one up to take the leading role. Just as Christ (enabled by the Spirit) accomplished redemption, so the Spirit (making Christ present in faith) applies it. Nowhere in the twofold economy is there a simple departure or complete absence of one of the agents. We are always in the Father’s two hands at once.

The work of the Son and the work of the Spirit, while distinct, are so intimately linked that it is hard to do justice to their profound unity. Consider, finally, the question of means and ends. Which of the two missions is the means and which is the end? Thinking in terms of redemption accomplished and applied, it is easy to consider the Spirit’s work as the means of delivering the Son’s work. In that case, the Son does the thing itself—reconciling God and man—and the Spirit serves his work by applying it to individual lives. Pentecost, in this view, happens in order to fulfill and extend Calvary and Easter. On the other hand, when we consider the intimacy of spiritual fellowship that the indwelling of the Holy Spirit involves, it begins to look as if all God’s ways lead up to the sending of the Spirit.

If God’s goal is to dwell among his people, the atonement was a necessary step to make that indwelling possible. The temple of human nature had to be cleansed to make it ready for the Spirit’s indwelling. So the Son by incarnation prepared one perfect human temple, his own body, for the Spirit to be present in. And by atonement the Son purified the other temples, preparing them to receive the Spirit on the basis of the Son’s finished work. “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us . . . so that we might receive the promised Spirit through faith” (Gal. 3:13–14). Calvary and Easter, in this view, happen in order to make Pentecost possible. If we have to ask whose work is the means and whose is the end, our answer must be either that the question is badly formed, or that each of them is a means to the other. The Spirit serves the Son by applying what he accomplished, and the Son serves the Spirit by making his indwelling possible. Both Son and Spirit, together on their twofold mission from the Father, serve the Father and minister to us.

If we hear about the Trinity at all in relation to salvation, we are likely to hear something to the effect that “it takes the entire Trinity to save one soul.” This is true, but not very specific. The real insight into God’s plan and purpose awaits us when we learn to see specifically how the persons of the Trinity are distinctively at work in salvation: the Father sends his two emissaries, the Son accomplishes salvation, and the Spirit applies it. Anglican bishop Robert Leighton said it even more helpfully and precisely:

We know that this HolyTrinity co-operates in the work of our salvation: the Father hath given us His Son, and the Son hath sent His Spirit, and the Spirit gives us faith, which unites us to the Son, and through Him to the Father. The Father ordained our redemption, the Son wrought it, and the Spirit reveals and applies it.26

From its ordaining, to its accomplishing, to its application, the economy of salvation is the one great plan of God to simultaneously save us and make himself known to us. As John Owen said, by giving his Son for us and giving his Spirit to us, the Father manifested “the glory of the whole blessed Trinity; which is the utmost end of all the works of God.”27 One sender, the Father, gives shape to salvation history by sending two emissaries, the Son and the Spirit, to carry out the plan of salvation. The Father’s two hands give shape to the economy.

THE SON AND THE SPIRIT AMONG US

We are ready for the next step. The Son and Spirit do not just construct or configure the economy of salvation; they actually bring it into being by showing up. They constitute the history of salvation by their presence because it would not be here without their being in it. The plan of salvation is above all a plan for the Son and the Spirit to arrive among us in the fullness of time, and it is by being here that they give the economy its shape. Because the Father sends them on their joint mission, the Son and the Spirit are the way God is with us to transform our history of sin and ignorance into his history of salvation and revelation (see Diagram 4.4).

God the Father is intimately involved with the economy of salvation but not by being sent. Even when Jesus promised that the Father would come to those who love the Son, he did not say that the Father would be sent: “If anyone loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him” (John 14:23). Jesus went on to talk about how the Father had sent him(v. 25) and would later send the Holy Spirit in Jesus’ name (v. 26). The Father loves by sending; the Son and the Spirit love by being sent. In the diagram above, the Father’s indirect, or unsent, presence in the economy of salvation is indicated by the fact that the Son and the Spirit actually come to occupy places on the grid of salvation history, and the Father is the source who remains intimately and inwardly connected with them. “He who sent me is with me,” said Jesus. “He has not left me alone, for I always do the things that are pleasing to him” (John 8:29). You could say the Father is not here, but it would be better to say he is here in the Son and the Spirit or he is here by sending them. The way God gives himself to us is that the Father gives the Son and the Spirit, sending them to redeem us and reveal the Trinity. In Trinitarian theology, the word for the sending of these two persons is mission. We can talk about their coming from the Father to us as their being sent on their respective missions, bearing in mind that the two missions are not separate from each other but mutually entwined in the ways we already explored.

So the Son and the Spirit fulfill the Father’s will by taking their stand here among us. They do not just send messages, envoys, or influences; they show up in person. And when they show up in person, they behave as themselves. Their eternal personalities, we might say, are exhibited here in time. We can see this most clearly in the case of the incarnate Son, who should always be the focus of our attention. We need to understand Jesus as the eternal Son who behaves like the Son on earth as he does in heaven and in time as he does in eternity. He was always the co-eternal, co-equal Son of God who always delighted in the presence of the Father, and when he took on human nature to save us, he continued to be the co-eternal, co-equal Son of God, still delighting in the presence of the Father.

When the Word who was God and was with God in the beginning (John 1:1–2) took the astonishing step of becoming flesh and dwelling among us (John 1:14), what changed about him? A moment’s thought shows that his divine nature did not change, since that would mean not only that he stopped being God, which is enough of a frightful and unbiblical conclusion, but also that there stopped being a God at all, since the divine nature itself would have changed into human nature. No, God remained God, and the Word remained God, when he became flesh. “Became,” in the incarnation, cannot mean “transformed into,” or “underwent a change in which he stopped being one thing and turned into another thing.” When the Word became flesh he took human nature to be his own, and he added a complete, real human existence to his eternal self.28

But here is the crucial thing to notice, the great, open secret at the heart of the gospel of God: when the Word became flesh, the sonship of the second person of the Trinity did not undergo any change either. It was the eternal Son, whose personal characteristic is to belong to the Father and receive his identity from the Father, who took on human nature and dwelled among us. His life as a human being was a new event in history, but he lived out in his human life the exact same son-ship that makes him who he is from all eternity as the second person of the Trinity, God the Son. So when he said he was the Son of God, and when he behaved like the Son of God, he was being himself in the new situation of the human existence he had been sent into the world to take up.

Nobody has described this continuity better than Austin Farrer (1904–1968), the Anglican theologian who was a close friend of C. S. Lewis. Farrer pointed out that the Gospels do not portray Jesus as somebody who walked around behaving like he was God. Instead, they portray him as walking around behaving like the Son of God. “We cannot understand Jesus as simply the God-who-was-man. We have left out an essential factor, the sonship.”29 When we leave out that sonship, we may think we are affirming the deity of Christ more clearly (“he is God” is a simpler statement to teach and defend than “he is the Son of God”), but in fact we are obscuring the Trinitarian revelation. The loss is too great; we will miss so much that is right there in Scripture. “What was expressed in human terms here below was not bare deity; it was divine sonship,” said Farrer.

God cannot live an identically godlike life in eternity and in a human story. But the divine Son can make an identical response to his Father, whether in the love of the blessed Trinity or in the fulfillment of an earthly ministry. All the conditions of action are different on the two levels; the filial response is one. Above, the appropriate response is a co-operation in sovereignty and an interchangeofeternal joys.Then the Songives backto the Father all that the Father is. Below, in the incarnate life, the appropriate response is an obedience to inspiration, a waiting for direction, an acceptance of suffering, a rectitude of choice, a resistance to temptation, a willingness to die. For such things are the stuff of our existence; and it was in this very stuff that Christ worked out the theme of heavenly sonship, proving himself on earth the very thing he was in heaven; that is, a continuous perfect act of filial love.30

As Farrer said, it is impossible to imagine how God would act if God were a creature. To put the question that way is to force ourselves into constant, unresolved paradox: Would he act like the creator, or like a creature? What action could he take that would show him to be both? When the incarnate God walked on water, was he acting like the creator or the created? None of these questions are the kind of questions the New Testament puts before us. What the apostles want to show is that Jesus was the Son: he came, lived, taught, acted, died, and rose again as the Son of God. Everything we usually say about the two natures of Christ is true, because Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man. The Bible does not teach less than that, but it does teach more. While our temptation is to rush past his sonship to get to his deity, the Bible does the opposite, often rushing past his deity to dwell on his sonship. When the Word became flesh, John tells us, the apostles saw his glory, “glory as of the only Son from the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). The word of life that they heard, saw, and touched with their hands was the one who was “with the Father and was made manifest” (1 John 1:1–2).

The temptation to gloss over the fact that Jesus was the Son, in our hurry to get to the fact that he was God, is a temptation to be resisted. His sonship explains so much about what he did among us because it is the secret to his personal identity. “God” describes what Jesus is, but “Son” describes who he is. That is why the perception of his sonship takes us into the heart of the doctrine of the Trinity.

A cross-cultural illustration from the mission field is appropriate here. Missionary bishop Lesslie Newbigin (1909–1998) described the challenge of finding the right terms for proclaiming the gospel to a tribal culture for the first time. The missionary gathers information about what the tribe already understands about deity. After sorting through various local and territorial powers of the spirit world, he surfaces a concept of a strongest, highest, or oldest god above those lesser forces. This is much closer to the biblical idea of the one God, so it is a starting point. “Does one say that ‘Jesus’ is the name of that one God?” No, cautioned Newbigin, for that is not the main idea of the New Testament. “The truth is that one cannot preach Jesus even in the simplest terms without preaching him as the Son. His revelation of God is the revelation of ‘an only begotten from the Father,’ and you cannot preach him without speaking of the Father and the Son.”31 Newbigin’s warning applies not only to other cultures but to our own, because we are tempted to regard the Trinitarian theology that is based on the sonship of Christ as “a troublesome piece of theological baggage which is best kept out of sight when trying to commend the faith to unbelievers.”32 Of course we don’t need to be saying the word Trinity all the time in our evangelism and preaching. But if we squint at Christ’s sonship and rush past his relation to the Father, we are missing what God has revealed about himself and settling for less than the full counsel of God.

What is so wonderfully clear with regard to the Son—that he is himself here with us just as he has eternally been himself in the happy land of the Trinity—is also true of the Holy Spirit. It is harder to perceive the distinct personality of the Spirit, though, partly because the Spirit is so successful in his work of focusing our attention on Jesus. Nevertheless, the same thing is true of both of them: when we meet the Son and the Spirit in salvation history, we meet divine persons. They are eternal, and there was never a time when they did not already exist as persons of the Trinity. Their coming into our history is not their coming into existence. But their coming into our history is an extension of who they have always been in a very specific, Trinitarian way.

When the Father sends the Son into salvation history, he is doing something astonishing: he is extending the relationship of divine son-ship from its home in the life of God down into human history. The relationship of divine sonship has always existed, as part of the very definition of God, but it has existed only within the being of the Trinity. In sending the Son to us, the Father chose for that line of filial relation to extend out into created reality and human history. The same is true for the Holy Spirit: when he is sent to be the Spirit of Pentecost, who applies the finished work of redemption and lives in the hearts of believers, his eternal relationship with the Father and the Son begins to take place among us. Having always proceeded from the Father in eternity, he now is poured out by the Father on the church.

There are helpful terms available for all this in the traditional theological categories of Trinitarianism. At the level of the eternal being of God, the Son and the Spirit are related to the Father by eternal processions. The Son’s procession is “sonly,” or filial, so it is called generation. The Spirit’s procession is “spiritly,” so it is called spiration, or, in a more familiar word, breathing. Those two eternal processions belong to God’s divine essence and define who he is. The living God is the Trinity: God the Father standing in these two eternal relationships to the Son and the Spirit. We have already discussed this in some detail in the chapter on “the happy land of the Trinity,” where we emphasized that the processions would have belonged to the nature of God even if there had never been any creation or any redemption. But now we come to the message of salvation itself and make the leap from God’s eternal being to the temporal salvation he works out in the economy. The leap is an infinite one that only God could have made. By God’s unfathomable grace and sovereign power, the eternal Trinitarian processions reach beyond the limits of the divine life and extend to fallen man.

Behind the missions of the Son and the Spirit stand their eternal processions, and when they enter the history of salvation, they are here as the ones who, by virtue of who they eternally are, have these specific relations to the Father. For this reason, the Trinity is not just what God is at home in himself, but that same Trinity is also what God is among us for our salvation. In an earlier chapter we mentioned some of the terms that theology has used for referring to the realm of the eternal processions: the ontological Trinity, the essential Trinity, the Trinity of being, or the immanent Trinity (immanent meaning “internal to” itself). Now we can say that what is present in the economy is that Trinity, as the Father sends the Son and the Spirit to be who they are here in our midst, to save us and reveal God to us.

The eternal Trinity is truly present in the gospel Trinity. This changes everything about our salvation, our knowledge of God, and our experience of God, because it takes us straight to the center of God’s revealed ways. This is how God gives himself to us: by the Father giving the Son and the Spirit. This is how God is with us: in Christ and the Spirit of Christ. This is how we know God: as he truly is, as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The whole field of Christian life and thought is thus open for biblical, Trinitarian exploration. But there is also a relatively minor point that is worth noting, and it has to do with where our minds go when we think of the doctrine of the Trinity. It is easy to fall into the habit of thinking that “Trinity” points to some set of facts about God which, while true, have nothing to do with us. When most Christians hear the word Trinity, their immediate mental response is to reach for an analogy: Is the Trinity kind of like a shamrock, or like the three states of matter (solid, liquid, gas), for instance the one substance H2O being ice and water and steam? They do this, I think, because of a mental habit of associating the Trinity with a logical problem, the problem of reconciling three and one. But while there is a time and a place for coming to terms with that problem, and while analogies can offer some limited help on that occasion, we have learned something different from the shape of the economy of salvation. We have learned to associate “Trinity” with the incarnate Son and the outpoured Spirit.

When we talk about Jesus, sent by the Father to work in the Spirit, we should know that we are talking about the Trinity. Our thoughts and affections should jump to the Gospels and the gospel, the story of Jesus and the present encounter with him, rather than to shamrocks and steaming icebergs. The whole point is that the presence of the Son and Spirit themselves, sent by the Father into the economy of salvation, is the Trinity. The eternal Trinity is the gospel Trinity. These persons in the gospel story are not what the Trinity is like—they are the Trinity. We will see how this changes everything about how we look for the signs of the Trinity in the various elements of the church’s life and work. For now, it is enough to underline the new mental associations, the whole new habit of associative thinking, that we gain from attending to the economy. Away with tropical icebergs! Shamrocks begone! In the gospel we have God the Trinity.

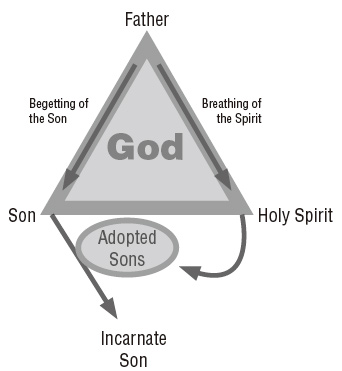

ADOPTION INTO THE TRINITY

Recovering the explicitly Trinitarian theology of our evangelical forebears can provide us with some new ideas, categories, and terminology to use in understanding the gospel. Talking in terms of eternal processions and temporal missions may be novel for our generation, but it was the common stock of evangelical theology until fairly recently. New to us, these ideas will be reinvigorating for evangelical life and thought. But the most exciting thing about recovering the Trinitarian depth of the gospel is that it equips us to use familiar terms with a greater understanding of what they have really meant all along. Classic evangelical Trinitarianism, once we have recovered it for contemporary use, restores some of our most familiar and conventional terms for salvation to their original depth and power. The most important instance of this restoration is the way this Trinitarian background makes the biblical doctrine of adoption come to life.

Adoption is a central biblical description of how God saves. It emphasizes the quality of the new relationship that God brings us into, a relationship of having been made into his children. In explicitly Trinitarian terms, this means that God brings us into the relationship of sonship that has always been part of his divine life. When we become sons of God, we are joined to the sonship of the incarnate Son, which is in turn the human enactment of the eternal sonship of the second person of the Trinity. Sonship was always within God, and it came to be on earth as it is in heaven, in the person of the incarnate Christ. Every time we hear the biblical proclamation that we have been made God’s children, we should hear the deep incarnational and Trinitarian echoes of this good news: “See what kind of love the Father has given to us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are” (1 John 3:1). Paul declares, “God sent forth his Son . . . so that we might receive adoption as sons. And because you are sons, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Gal. 4:4–6). Paul’s way of putting it is especially helpful because it also refers to the work of the Holy Spirit in bringing about our sonship. The Spirit is the one who baptizes us into Christ, forms us into sons on the pattern of his sonship, and even takes up residence within us as the principle of sonship that enables us to call on God as Father.

When the eternal Son becomes the incarnate Son, his eternal, filial relation to the Father takes on a human form. He does not become a different person but remains the Son. His procession from the Father extends into a mission from the Father. Thus divine sonship appears among humans, in Christ. The Holy Spirit, as we have already seen, is involved in this mission of the Son to be incarnate. He brings about the conception of Jesus and empowers Christ in his ministry, among other things. But the role of the Spirit is especially important in incorporating believers into this sonship of Christ. It is the Spirit of adoption (Rom.

8:15), or the Spirit of the Son (Gal. 4:6), who makes us children of the Father. He puts us into the place of sonship.

This is how “the two hands of the Father” work simultaneously to bring us into fellowship with God: the Son opens up the path of human sonship, and the Spirit puts us into it. This two-handedness of adoption was the main idea of an important article in The Fundamentals, that interdenominational publication that marked the conservative evangelical revolt against modernism in the early years of the twentieth century. Published serially in twelve volumes between 1910 and 1915, the publications were sent free of charge to Christian workers around the world. The 1917 republication of The Fundamentals, under the editorial hand of R. A. Torrey, consisted of ninety essays printed in four volumes.33 Torrey put the essays into an orderly sequence in this edition, making The Fundamentals a popular synthesis of conservative biblical scholarship, theology, and apologetics.

The Fundamentals have sometimes been criticized for a lack of theological breadth, as they focused on the handful of doctrines that were under attack by modernism. In ninety chapters on a range of disputed issues, for example, there is not a chapter on the Trinity. Uncharitable interpreters of The Fundamentals (and there have been hardly any sympathetic scholarly interpretations in recent decades) have taken this conspicuous absence as evidence of the narrowness and imbalance of The Fundamentals project. But the uncharitable reading is too facile to fit the case. Lacking a Trinity chapter, The Fundamentals nevertheless exhibit a robust evangelical Trinitarianism precisely at this point of the doctrine of salvation by adoption. This is best exemplified in Charles Erdman’s essay “The Holy Spirit and the Sons of God.”34

Erdman begins this essay by pointing out that “due importance has not been given to the peculiar characteristic of the Pentecost gift in its relation to the sonship of believers.”35 After describing the “sonship in glory” that Jesus enjoyed, Erdman goes on to say that “when the disciples were baptized with the Spirit on the day of Pentecost they were not only endued with ministering power, but they also then entered into the experience of sonship.”36 Working out that experience of sonship in the believers, according to Erdman, was the proper task of the Holy Spirit for at least two Trinitarian reasons. First, the Holy Spirit forms believers into sons because his work is based on the completed work of Christ the Son: “through the heavendescended Spirit the sons of God are forever united with the heavenascended, glorified Son of God.” Second, the Spirit forms believers into sons because he always works toward that perfect sonship that he knows to belong to Christ: “the sum of all His mission is to perfect in saints the good work He began, and He molds it all according to this reality of a high and holy sonship.”37 The perfection of Christ “was preeminently the life of a Son of God and not only of a righteous man; of a Son ever rejoicing before the Father, His whole being filled with filial love and obedience, peace and joy.”

The Trinitarian background of adoption is striking. The Heidelberg Catechism raises the question, “Why is Christ called the only begotten Son of God, since we are also the children of God?” and answers it, “Because Christ alone is the eternal and natural Son of God; but we are children adopted of God, by grace, for his sake.”38 The catechism is concerned to point out the absolute difference in the way this sonship is experienced by these two very different kinds of sons. Christ, and Christ alone, is the Son of God by nature and from eternity. Believers, on the other hand, are made to be sons by adoption, through the gracious decision of God, for the sake of Christ the Son. The difference is infinite. But alongside that difference is the striking element of similarity, indeed of sameness, and that sameness the relation of sonship.

Bishop Robert Leighton described the greatness of this adoption in God’s overall plan by saying, “For this design was the Word made flesh, the Son made man, to make men the sons of God.”39 As any responsible interpreter of this topic must do, Leighton underlined the difference: “It is a sonship by adoption, and is so called in Scripture, in difference from His eternal and ineffable generation, who is, and was, the only begotten Son of God.” But Leighton also emphasized that this adoption is something deeper than a mere “outward relative name” as in human adoption or “that of men.” Divine adoption comes from deeper in God’s identity and penetrates deeper into the being of the redeemed than human adoption can. We see this in two ways in Scripture. First, God’s adopted children are also said to be regenerated or born again from him (1 John 1:13). Second, they are said to have received the Spirit:

A new being, a spiritual life, is communicated to them; they have in them of their Father’s Spirit; and this is derived to them through Christ, and therefore called His Spirit. Gal. 4:6.They are not only accounted of the family of God by adoption, but by this new-birth they are indeed His children, partakers of the Divine nature.40

There is an important strand of the evangelical tradition that seems almost to dare itself to say the highest things possible about the sonship that believers enter into through the work of the Spirit and how it is the same sonship as Christ’s. Leighton seems to have been a participant in this tradition. One of the most strident was Robert S. Candlish (1806–1873), whose book The Fatherhood of God argued that our relationship to the Father was in “substantial unity” with the sonship of the human nature of Christ and that “the only difference between our enjoyment of sonship and Christ’s was that Christ enjoyed the privileges of sonship before we do, but not in a different manner.” This must be saying too much. But Sinclair Ferguson, commenting on this incautious language, could not bring himself to lodge any complaint more serious than the warning that “perhaps Candlish went beyond what is written, but it is not easy to show that he went against what is written.”41 At all costs, we do not want to diminish God’s glory by claiming an unwarranted intimacy with him, one that ignores our permanently subordinate position as creatures or minimizes our alienated condition as sinners. But we also want to confess the God-sized, God-shaped greatness and goodness of the actual salvation brought to us in the gospel. Doing so has brought us to the place where we can and must say that God the Son became man so that men could become sons of God.

In fact, once the Trinitarian background of adoption emerges into plain sight, these high, almost extravagant, claims for our sonship must be made. There is something intoxicating in the insight that we are sons of God in God the Son. It transposes our understanding of salvation into a higher key, transfigures our notions of what God has done for us in Christ and the Spirit into something we can hardly look at directly, and transforms our relationship with God into a conscious enjoyment of filial blessing. We have been looking to see why the evangelical tradition has said that “the things of the gospel are depths,” even “the deep things of God.” Trinitarian adoption brings into our view the ultimate grounds for saying this: sonship is on earth as it is in heaven. The clear dividing line between God’s essence and his actions is still in place. There is never any compromise of the blessedness and self-sufficiency of God in the happy land of the Trinity. There is still an infinite distinction between who God is in himself and what he freely chooses to do for us. But adoption is the mightiest of God’s mighty acts of salvation, and without transgressing the line between the divine and the created, God does reach across it and establish a relationship more intimate than we could have imagined. In adopting children, God does something that enacts, for us and our salvation, his eternal being as Father, Son, and Spirit among us. Eternal sonship becomes incarnate sonship and brings created sonship into being. In this case, what God does is who he is.

“Really, thought becomes giddy,” said Marcus Rainsford, “and our poor feeble minds weary, in contemplating truths like these, but they are resting places for faith.” Rainsford (whom we met as Dwight Moody’s interlocutor in the Gospel Dialogues) spoke for evangelical Trinitarianism when he said that these things are not secrets that we have somehow managed to pry our way into but are things that the Son intentionally made known to us by speaking about them to his Father in front of his disciples: “It was in order that our faith might be strengthened, our hope established, and our love deepened, that the Lord uttered these words to His Father—not in private, but in the hearing of His disciples.”42