5

INTO THE SAVING LIFE

OF CHRIST

(Or, What’s Trinitarian about a Personal Relationship with Jesus)

When I accept Christ as my Savior, my guilt is gone, I am indwelt by the Holy Spirit, and I am in communication with the Father and the Son, as well as the Holy Spirit—the entire Trinity.

FRANCIS SCHAEFFER

The Father’s love gave Christ to them, Christ’s love gave Himself for them, and the Holy Ghost’s love reveals and applies to them the salvation of God.

MARCUS RAINSFORD

Is the gospel mainly about Jesus Christ or mainly about the Trinity? That is a question so badly formulated that it would not deserve an answer, except that it undeniably gives voice to a tension that is widely felt in evangelical circles and beyond. One of the reasons for the ambivalence that some evangelicals feel toward the doctrine of the Trinity is that it can seem to be a distraction from the simple message about salvation in Christ. And evangelicals are famous for being focused on Jesus Christ and the conscious experience of personal salvation by receiving Christ as Savior. We have already seen the divine scope and the Trinitarian shape of the economy of salvation. Now we need to see, as clearly as possible, that the gospel of the Trinity is not an alternative gospel to the experience of personal salvation through Christ. There are not two different messages here but a single proclamation of good news that is simultaneously Christ-centered and Trinity-centered. There is never any need to play the doctrine of the Trinity off against salvation in Christ, because they are centered on the same reality. The more Trinity-centered we become, the more Christ-centered we become, and vice versa.

CHRIST-CENTERED, NOT FATHER-FORGETFUL OR SPIRIT-IGNORING

The main reason that a Christ-centered message can never be in real tension with a Trinity-centered message is that the two messages are concentric. When you declare that Jesus Christ is the center of your message, you are committing yourself to proclaim him and whatever is central to his own concerns. But Jesus himself is always centered on the work of the Father and the Spirit, so successfully focusing on Christ logically entails including the entire Trinity in that same focus. It is incoherent to hold to Jesus without simultaneously holding to the Father and the Spirit. Unfortunately, while it is incoherent, it is not impossible. Many people fall prey to this temptation of trying to grasp Christ in abstraction from the Father and the Spirit.

In his own ministry Jesus apparently found himself confronting the same tendency. John’s Gospel reports repeatedly that Jesus talked over the heads of his listeners when he taught about his relationship to the Father and the Spirit. “They did not understand that he had been speaking to them about the Father,” interjects the narrator at John 8:27; and again at John 7:39, “This he said about the Spirit, whom those who believed in him were to receive, for as yet the Spirit had not been given, because Jesus was not yet glorified” (John 7:39). From explanations like this, the reader gets the impression that Jesus was teaching about the Trinity, but his disciples had not yet learned how to see Jesus himself in Trinitarian perspective. Similarly in Acts 1:6–8, the disciples come to the risen Christ and ask, “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” Jesus’ reply is striking, not only because it sets aside their expectations about the timeline for the kingdom, but also because it points them away from their expectations about what Jesus will do, to the work of the Father and the Spirit: “It is not for you to know times or seasons that the Father has fixed by his own authority. But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you will be my witnesses . . .”

Of course Jesus is not telling the disciples to stop focusing on him. We are at all times to “[look to] Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith” (Heb. 12:2). But we are to look to him in a way that lets us see him situated in his relationships to the Father who sent him and the Spirit whom he sends. Unless we see Jesus in this way, we fail to see him as who he actually is. The consequences are inevitably confusion and a loss of spiritual power, usually brought about by substituting Jesus into a role that ought to be filled by the other persons of the Trinity. For example, there is a metaphorical sense in which Jesus plays a fatherly role towards believers. But the main thrust of the New Testament message is certainly not that Jesus is our father; it is that the Father of Jesus is our Father. To substitute Jesus for the Father is to miss the plain meaning of the Bible by ignoring his Father. This is to focus on Jesus in a way that detracts from his own message. The problem is not in being too Christ-centered, but in using Christ-centeredness to enable an unbiblical Father-forgetfulness.

Another example is the tendency to think of Jesus as the one who lives in our hearts without making reference to the Holy Spirit’s role as the direct agent of indwelling. Once again, there is a grain of truth to this: Jesus does dwell in the hearts of believers, and a handful of passages in the New Testament describe our relationship to Jesus this way (especially Eph. 3:16–17). But the dominant message of the Bible is that we are in Christ, not that Christ is in us. And on those few occasions when Christ is said to be in us, the work of the Spirit is nearly always mentioned. This is not a theological subtlety noted only by overly precise theologians but a special emphasis of Scripture. Billy Graham, who has certainly popularized a powerful message about accepting Jesus into your heart, identified this indwelling work of the Spirit in salvation as something that needed special emphasis:

One point about the relation of the Holy Spirit and Jesus Christ needs clarification. The Scriptures speak of “Christ in you,” and some Christians do not fully understand what this means. As the God-man, Jesus is in a glorified body. And wherever Jesus is, His body must be also. In that sense, in His work as the second person of theTrinity,Jesus is now at the right hand of the Father in heaven. . . . For example, consider Romans 8:10 (KJV), which says,“If Christ is in you, the body is dead because of sin.” Or consider Galatians 2:20,“Christ lives in me.” It is clear in these verses that if the Spirit is in us, then Christ is in us. Christ dwells in our hearts by faith. But the Holy Spirit is the person of the Trinity who actually dwells in us, having been sent by the Son who has gone away but who will come again in person when we shall literally see Him.1

Once again, it is not wrong to affirm that Jesus lives in our hearts, but it is wrong to ignore the Holy Spirit’s role in that indwelling.

It is interesting to see how this signature evangelical teaching about Christ living in our hearts has devolved and degraded over the years. If you trace it to its origin, it is a relentlessly Trinitarian message, as we have already seen in Billy Graham’s presentation of it in the 1970s. An earlier presentation of the message of Jesus in our hearts—one that the Billy Graham team made extensive use of—is Robert Boyd Munger’s widely reprinted 1951 sermon, “My Heart—Christ’s Home.” Munger begins with Ephesians 3:16–17 and then says, “Without question one of the most remarkable Christian doctrines is that Jesus Christ himself through the Holy Spirit will actually enter a heart, settle down and be at home there. Christ will live in any human heart that welcomes him.” Munger definitely describes the indwelling of Christ as being “through the Holy Spirit” in this opening sentence. In the next few pages, he describes Christ’s ascension and the subsequent descent of the Spirit that made the indwelling possible: “Now, through the miracle of the outpoured Spirit, God would dwell in human hearts.”2

From this clearly Spirit-honoring beginning point, Munger goes on to develop the homey application that made his sermon a classic, as Christ the guest is shown through each room of the heart-house, extending his lordship into every part. Even that element of Munger’s sermon can be traced further back to John Flavel’s 1689 book Christ Knocking at the Door of Sinners’ Hearts, or, A Solemn Entreaty to Receive the Saviour and His Gospel. Flavel, whose radically and consistently Trinitarian theology we saw in the previous chapter, places Jesus decidedly in the context of the Father and the Spirit. Flavel’s book is even based (like Munger’s) on Jesus’ saying in Revelation 3:20, “Behold, I stand at the door and knock.” He carefully distinguishes the original intention of that passage (a warning to a church) from its legitimate extended sense (a personal invitation to sinners), and then dilates on the personal application: “Thy soul, reader, is a magnificent structure built by Christ; such stately rooms as thy understanding, will, conscience, and affections, are too good for any other to inhabit.”

With the Trinitarian background in place, the message of Jesus knocking on the door of a sinner’s heart is a recognizably Trinitarian gospel. It is not Father-forgetful or Spirit-ignoring in its classic exponents such as John Flavel, Robert Boyd Munger, or Billy Graham. Surely these three witnesses count as an evangelical pedigree and can bolster our confidence in the theology presented through countless flannelgraph images of Christ knocking on the door of a fuzzy, felt heart-house. Surely with this Trinitarian lineage in place, we can affirm that all the flannelgraphs are true! But we have to admit that the Trinitarian connections are fairly easy to lose. They may have been there in Flavel, Munger, and Graham, but they are often lost in translation, especially in recent decades. Jesus is still presented as knocking on the heart’s door, but too often in a Father-forgetful and Spirit-ignoring way.

Just as we can lapse into substituting Jesus for our heavenly Father, we can replace the Spirit with Jesus when we talk about the divine indwelling. Taken together, these two errors constitute an unfortunately common distortion of the biblical message. They replace the Trinity with Jesus, or they center on Jesus in a Father-forgetful, Spirit-ignoring manner. Jesus becomes my heavenly Father, Jesus lives in my heart, Jesus died to save me from the wrath of Jesus, so I could be with Jesus forever. Once again, there is no such thing, in Christian life and thought, as being too Christ-centered. But it is certainly possible to be Father-forgetful and Spirit-ignoring. At their best, and from their roots, evangelicals have avoided that. In recent decades, though, it requires vigilance to make sure we are presenting the evangelical message with recognizable Trinitarian connections. What Would Jesus Do? He would do the will of the Father in the power of the Spirit. He would send the Spirit to bring us to the Father.

UNION WITH CHRIST

Being properly Christ-centered always entails being Trinity-centered. Everyone who receives the salvation described in the New Testament is saved by being joined to Christ as the incarnate, atoning second person of the Trinity. But when we go on to work out our understanding of that salvation, we need to keep the full scope of the economy of salvation in place. When it comes to soteriology, the doctrine of salvation, there is a watershed that marks some as believers of one type and some as believers of another type. The watershed is a Trinitarian grasp of union with Christ.

The New Testament idea of salvation is that God has dealt with us by dealing with Jesus Christ: the life, death, and resurrection of Christ are the place where God the Father took hold of human nature to save it, dealt with sin decisively, and poured out his Spirit without reserve. Then and there God and man became intimately united and worked out the grievances that threatened to overturn their covenant relationship. In Christ, God was so overwhelmingly active and available that once and for all the second half of the covenant was kept: “I will be your God and you will be my people.” It all happened in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Since salvation is all accomplished in the life of Jesus, our salvation is a matter of being joined to him or united to him, or as Paul says succinctly: being “in Christ.” God apparently has two steps for saving people: (1) accomplish salvation in Christ; and (2) put people into Christ. As Paul says in 1 Corinthians 1:30, “because of him you are in Christ Jesus,” which could be rendered “by God’s doing you are in Christ,” or as the KJV has it, “of him are ye in Christ Jesus.” This fact of union with Christ is the core of Christian soteriology. John Calvin put it classically when, having finished a thorough treatment of the work of God in Christ, he opened the third book of The Institutes with these words:

We must now see in what way we become possessed of the blessings which God has bestowed on his only-begotten Son, not for private use, but to enrich the poor and needy.And the first thing to be attended to is, that so long as we are without Christ and separated from him,nothing which he suffered and did for the salvation of the human race is of the least benefit to us.To communicate to us the blessings which he received from the Father, he must become ours and dwell in us. Accordingly, he is called our Head, and the first-born among many brethren, while, on the other hand, we are said to be ingrafted into him and clothed with him, all which he possesses being, as I have said, nothing to us until we become one with him.3

Note the Trinitarian contours here: the Father puts all the blessings of salvation onto the incarnate Son, and the Spirit unites us to that. It is not enough to say that faith links us to the benefits of Christ, because we must “climb higher and examine into the secret energy of the Spirit, by which we come to enjoy Christ and all his benefits.”

Salvation begins and ends in union with Christ, and all the blessings of salvation flow naturally from that union. This should be familiar territory to anybody who understands the gospel. But the Trinitarian shape of this application of redemption guards against numerous mistakes. Mainly, it lodges the saving life of Christ in the work of the Father and the Spirit, and thus keeps us from falling back into a faux Christocentrism that is both Father-forgetful and Spirit-ignoring. But it also keeps us from declining into a couple of defective understandings of what salvation is.

Deficient soteriology type A: rather than centering everything on the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, some people conceive of salvation as essentially a here-and-now encounter in which they cry out to a higher power who hears their cry and performs an act of deliverance. The higher power is Jesus, and he has feelings of love toward them. How is this present act of deliverance related to the life of Jesus back then? At best, this soteriology thinks of the past event as a transaction that gives the present Christ his rights or abilities to save now, perhaps by settling an account with God. The emphasis of this soteriology falls on the emotional attitude of this present higher power toward the believer: “Jesus loves me.”

One way to see the difference between this soteriology and the biblical one is to mark how Paul speaks of the love of Jesus for the believer: “I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Gal. 2:20). The present-encounter soteriology says “Jesus loves me” in the present tense, but Paul hangs everything on the past tense of “Jesus loved me.” The present-encounter soteriology (like all soteriological self-misunderstandings by Christians) is maddeningly close to the truth: we do cry out to the powerful and present Jesus who does love us and will save here and now. But he saves us now and loves us now because he is the same yesterday and today, and because God the Holy Spirit places us into what God the Father has done in Christ so that we go to the cross and come out of the tomb in him. Galilee, Gethsemane, and Calvary are not just distant events in the prior biography of our present Savior. Christ is present to us through the Spirit, in the power of that finished work, and our salvation has the shape of dying and rising with him.

This brings us to deficient soteriology type B: This way of viewing salvation is focused on finding the right church with the right sacraments. Jesus started a spiritual organization that is still in existence, and it administers water baptism and Communion with bread and wine. Locating this church from among the plethora of options and getting into contact with the proper sacraments is what matters. There is less to say about this soteriology because its inadequacy is more obvious. It’s the classic case of the sacramental tail wagging the soteriological dog: if this is the way sacraments matter then nothing else matters, and there is no such thing as a doctrine of salvation that isn’t identical with locating the right sacraments. It is mainly worth mentioning because it succeeds in emphasizing what the present-encounter soteriology leaves out, which is a reference to the saving life of Christ.

What is so frustrating about this deficient soteriology is that it is obsessed with tasting and handling the Christ-ordained rituals, the very meaning of which is union with Christ: baptism in water means burial and resurrection with Christ; the bread and wine mean actual partaking of the body and blood of Christ rather than notional assent to facts about him. Yet these symbols can so easily become opaque and threaten to mean themselves rather than the things they signify. People who lapse into this soteriological misunderstanding are very close (much closer in many cases than the rival soteriology considered above) to recognizing union with Christ. In fact they recognize the form but misunderstand the content.

The right soteriology comes from a Christocentrism that is not in contradiction to a Trinity-centeredness. There are two movements or trajectories to consider here: one movement is the dying and rising with Christ, our mortification and vivification by being identified with his death and resurrection. That is the Christocentric focus. The second movement is the long line that traces how we are saved when God the Spirit unites us to what God the Father has done in the life of God the Son. That is the Trinitarian focus. It is based on the Trinitarian shape that the economy of salvation has. It is the horizon against which we must understand salvation in Christ. The deficient soteriologies can be overcome by a Christocentric perspective that is not Father-forgetful or Spirit-ignoring. May the eyes of our hearts be opened so we can see the power of God toward us who believe, in accordance with the power which he worked in Christ when he raised him from the dead and seated him at his own right hand (Eph. 1:18–21).

THE TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY OF FRANCIS SCHAEFFER

As we focus on the way all this Trinitarian theology comes into our own experience, it is high time we turn to another case study of classic evangelical teaching that presents these various elements in their proper proportions and with an eye toward experiencing it. Look at Francis Schaeffer’s words from his 1972 book True Spirituality. In the chapter entitled “The Supernatural Universe” he says:

Little by little, many Christians in this generation find the reality slipping away.The reality tends to get covered by the barnacles of naturalistic thought. Indeed, I suppose this is one of half a dozen questions that are most often presented to me by young people from Christian backgrounds: where is the reality? Where has the reality gone? I have heard it spoken in honest, open desperation by fine young Christians in many countries. As the ceiling of the naturalistic comes down upon us, as it invades by injection or by connotation, reality gradually slips away.

Schaeffer was in earnest about this cry for reality. He was not just reporting the “honest, open desperation” of “fine young Christians” who came to him in the early seventies; he had also asked these questions himself, in almost the same language, twenty years before. In the very next sentence he gives the answer as he had found it:

But the fact that Christ as the Bridegroom brings forth fruit through me as the bride, through the agency of the indwelling Holy Spirit by faith—this fact opens the way for me as a Christian to begin to know in the present life the reality of the supernatural. This is where the Christian is to live. Doctrine is important, but it is not an end in itself.There is to be an experiential reality, moment by moment.4

It would be easy to overlook one of the most important elements in this answer: the Trinitarian element. The road to spiritual reality, according to Schaeffer, is through an experienced reality of God but specifically of the fact “that Christ . . . brings forth fruit through me . . . through the agency of the indwelling Holy Spirit.” The reality Schaeffer invites us to understand and experience is a Trinitarian reality, an experience of God the Father through the Son and the Spirit. And the God whom Schaeffer points to in all his most popular writings, the God who is there and is not silent, is not God in general, but God the Holy Trinity. Schaeffer goes on, becoming more insistently Trinitarian as he develops the thought:

This experiential result, however, is not just an experience of ‘bare’ supernaturalism, without content, without our being able to describe and communicate it. It is much more. It is a moment-bymoment, increasing, experiential relationship to Christ and to the wholeTrinity.We are to be in a relationship with the wholeTrinity. The doors are open now: the intellectual doors, and also the doors to reality.5

Schaeffer attributes his effectiveness in later ministry to his encounter with the Trinity. In his 1974 position paper for the Lausanne congress on evangelization, Schaeffer tells the story of the deep period of doubt and perplexity in his life in 1951 and 1952. Troubled by the lack of spiritual reality in the Christian groups he worked with, Schaeffer began asking what was missing, and why. He thought his way all the way back to his original agnosticism and put all his beliefs and commitments back on the table for renegotiation. He paced back and forth for months or took long walks when the weather permitted. He notified his wife, Edith, that if he didn’t find what he needed in Christianity, he would reject it and then do something else with his life. His conclusion:

I came to realize that indeed I had been right in becoming a Christian. But then I went on further and wrestled deeper and asked, “But then where is the spiritual reality, Lord, among most of that which calls itself orthodoxy?” And gradually I found something. I found something that I had not been taught, a simple thing but profound. I discovered the meaning of the work of Christ, the meaning of the blood of Christ, moment by moment in our lives after we are Christians—the moment-by-moment work of the whole Trinity in our lives because as Christians we are indwelt by the Holy Spirit.That is true spirituality.6

Writing about this turning point in his life, Schaeffer later said: “Gradually the sun came out and the song came. Interestingly enough, although I had written no poetry for many years, in that time of joy and song I found poetry beginning to flow again . . . admittedly, as poetry it is very poor, but it expressed a song in my heart which was wonderful to me.”7 And there is a bit of poetry, first published in 1960 and later reprinted in the preface to 1974’s No Little People, which captures what Schaeffer was seeking and what he found:

To eat, to breathe

to beget

Is this all there is

Chance configuration of atom against atom

of god against god

I cannot believe it.

Come, Christian Triune God who lives,

Here am I

Shake the world again.

The “Christian Triune God who lives” did answer that prayer and shook the world through Schaeffer’s ministry.

In 1951 Francis Schaeffer had an encounter with the Trinity that revolutionized his life. It sparked the phase of his ministry for which we all remember him and put him in touch with a sense of spiritual reality he had lacked before: “a moment-by-moment, increasing, experiential relationship to Christ and to the whole Trinity. We are to be in a relationship with the whole Trinity.” But when this change came over him, he didn’t sit down and write a treatise on the Trinity; instead, he famously started writing about everything else under the sun. As a result, if you want the details of Schaeffer’s Trinitarian view of salvation (his soteriology), you have to piece it together from a few places scattered around his writings. The most programmatic statement of Schaeffer’s Trinitarian soteriology is in his book True Spirituality.8 He connects the dots this way:

The Holy Spirit indwelling the individual Christian is not only the agent of Christ,but he is also the agent of the Father.Consequently, when I accept Christ as my Savior, my guilt is gone, I am indwelt by the Holy Spirit, and I am in communication with the Father and the Son,as well as of the Holy Spirit—the entireTrinity.Thus now, in the present life, if I am justified, I am in a personal relationship with each of the members of the Trinity. God the Father is my Father; I am in union with the Son; and I am indwelt by the Holy Spirit.This is not just meant to be doctrine;it is what I have now.9

If you want even more detail on Trinitarian salvation, you have to follow Schaeffer into the land of direct, personal Bible study. His basic course in Bible knowledge has been published as the series Basic Bible Studies.10 The striking simplicity of these studies is underlined by the direct appeal Schaeffer makes to the reader:

It would be my advice that each time you do these studies, you speak to God and ask Him to give you understanding through the use of the Bible and the study together. If someone pursues these studies who does not believe that God exists, I would suggest that you say aloud in the quietness of your room: “O God, if there is a God, I want to know whetherYou exist.And I askYou that I may be willing to bow before You if You do exist.”11

What else would you expect from a Christian writer whose message was summed up in the affirmation, “He is there, and He is not silent”?

According to Schaeffer, every Christian who wants to understand salvation and the Christian life is obligated to come to grips with the biblical revelation on the subject: “It is central and important to our Christian faith to have clearly in mind the facts concerning the Trinity.” His Basic Bible Studies were designed to deliver those facts.

The first point in Schaeffer’s Bible study on the Trinity is that the God of the Bible is personal: God has plans that he considers in advance and then carries out with purpose (Eph. 1:4). Not only does he think but he takes action, real action in space and time (Gen. 1:1). And not only does he think and act, but he feels. He loves the world (John 3:16). “Love is an emotion. Thus the God who exists is personal. He thinks, acts, and feels, three distinguishing marks of personality. He is not an impersonal force or an all-inclusive everything. He is personal. When He speaks to us, He says ‘I’ and we can answer Him ‘You.’”

One of Schaeffer’s favorite phrases for the personhood of God was that he is “personal on the high order of Trinity,” and the next step in his basic Trinitarian Bible study is to state all the biblical evidence about unity and diversity in the God of the Bible. The Old Testament teaches, and the New Testament reaffirms, that there is only one God (Deut. 6:4; James 2:19). “But,” Schaeffer goes on, “The Bible also teaches that this one God exists in three distinct persons.” His first line of evidence for this claim is the divine plurals used in the language of the Old Testament: “Who will go for us?” (Isa. 6:8); “Let us make man in our image” (Gen. 1:26); “Let us go down there and confuse their language” (Gen. 11:7). “In this verse, as in 1:26, the persons of the Trinity are in communication with each other.”12

These Old Testament plurals would not be enough to prove the triunity of the one God all alone. They are odd enough to require some explanation: Why would a consistently monotheistic revelation use words like we, us, and ours? And they might point to a certain fullness or richness of God’s inner life. But solid Trinitarianism has to wait until the Son and the Spirit are directly revealed in the events of the New Testament. What Schaeffer primarily wants us to learn from these passages, however, is not triunity itself but the fact that it preexists creation. Combined with a few New Testament insights (“You loved me before the foundation of the world,” said Jesus to his Father in John 17:24), these plurals show that “communication and love existed between the persons of the Trinity before the creation.”13 And that mattered a lot to Schaeffer, because it means that when God reveals himself as Father, Son, and Spirit, he is revealing who has always been.

When he turns to the New Testament, Schaeffer highlights the baptism of Christ (Matt. 3:16–17) because of the clarity with which each of the three persons is shown there. He also points to a few of the passages where all three persons are named in a single verse: Matthew 28:19; John 15:26; and 1 Peter 1:2.14

With this biblical doctrine of God as Schaeffer’s foundation, his soteriology is explicitly Trinitarian. Under the heading of salvation, the Trinity is not the very first thing Schaeffer teaches. That priority is reserved for a classic Protestant statement of the biblical doctrine of salvation by grace alone through faith alone. But from that all-important point of entry, the very next thing Schaeffer wants to say is that what this justification introduces us into is a new relationship, or web of relationships, to the triune God:

This new relationship with the triune God is, then, the second of

the blessings of salvation, justification being the first. This new

relationship, as we have seen, is threefold:

1) God the Father is the Christian’s Father.

2) The only begotten Son of God is our Savior and Lord, our prophet,priest and king.We are identified and united with Him.

3) The Holy Spirit lives in us and deals with us. He communi cates to us the manifold benefits of redemption.15

In summary, commenting on 2 Corinthians 13:14, Schaeffer says, “The work of each of the three persons is important to us. Jesus died to save us, the Father draws us to Himself and loves us, and the Holy Spirit deals with us.”16

After the believer is placed in a saving relationship with the persons of the triune God, three consequences follow: (1) relationship to brothers and sisters in the church; (2) assurance of salvation; and (3) a Christian life characterized by the process of sanctification. In these studies Schaeffer devotes several sections to sanctification, equipping his readers with a good survey of the things they will need to know to live an intelligent Christian life. He highlights the difference between the event of justification and the process of sanctification, which is “a flowing stream involving the past. . . , the present, and into the future.”17 Salvation, as he had said in True Spirituality, “is a single piece, and yet a flowing stream.”18 Schaeffer also rounds out his teaching on sanctification with a great deal of practical advice about how Christians are to deal with sin and with an introduction to the basic spiritual disciplines.

True to Trinitarian form, though, one of the main things Schaeffer wants to say is that sanctification is a project of the entire Trinity, and he does so by surveying the way each of the three persons is related to Christian holiness. God the Father is active in our sanctification as the one who will accomplish it, and who sets the standard of it: “May the God of peace himself sanctify you” and “equip you with everything good that you may do his will, working in us that which is pleasing in his sight” (1 Thess. 5:23; Heb. 13:20–21).

Elsewhere Schaeffer says of the Father’s role, “When we accept Christ as our Savior, we are immediately in a new relationship with God the Father. . . . But, of course, if this is so, we should be experiencing in this life the Father’s fatherliness.”19

God the Son is involved in our sanctification in that it is the purpose for which he died: “Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her, that he might sanctify her, having cleansed her by the washing of water with the word . . . gave himself for us to redeem us from all lawlessness and to purify for himself a people for his own possession who are zealous for good works” (Eph. 5:25–26; Titus 2:11–14).20

God the Spirit is the holy one who makes us holy: “you were washed, you were sanctified . . . by the Spirit of our God . . . [and] are being transformed . . . from glory to glory. . . [by] the Lord, who is the Spirit . . . [and we are saved] through sanctification by the Spirit and faith in the truth” (1 Cor. 6:11; 2 Cor. 3:18; 2 Thess. 2:13 niv, nasb).21

Most of this richly Trinitarian understanding of salvation recedes into the background of Schaeffer’s writing. Outside of the Basic Bible Studies, he does not often work through the details of Trinitarian soteriology. But Schaeffer always spoke from a depth of insight that flowed from his 1951 experience of the reality of the Trinity in salvation. He wrote and spoke with a sense of God’s presence that was deeply personal and which he did manage to communicate to sympathetic listeners in all that he taught after 1951. Schaeffer’s Trinitarian awakening left its mark on his work in the strong sense of the personhood of God that colored all his expressions. It may be hard for evangelical Christians to hear the phrase “a relationship with God” as a radically Trinitarian claim, but that is how the language functioned for Schaeffer. Whenever he said “relationship,” you can bet there was Trinitarianism ringing in his ears: “Our relationship is never mechanical and not primarily legal. It is personal and vital. God the Father is my Father; I am united and identified with God the Son; God the Holy Spirit dwells within me. The Bible tells us that this threefold relationship is a present fact, just as it tells us that justification and Heaven are facts.”22

Of course, as the story of Schaeffer’s 1951 Trinitarian awakening makes clear, not every Christian is aware of the Trinitarian depths waiting beneath their spiritual lives. “It is,” Schaeffer warned, “possible to be a Christian and yet not take advantage of what our vital relationship with the three persons of the Trinity should mean in living a Christian life. We must first intellectually realize the fact of our vital relationship with the triune God and then in faith begin to act upon that realization.”23 And immediately after this warning he invited his readers to review the Basic Bible Study on the three new relationships that constitute the Christian life.

One of the most remarkable characteristics of Schaeffer’s teaching on the subject of the Trinity, and the reason we have investigated it in some depth here, is how it consistently combined two virtues: simplicity and depth. Over and over in his teaching on the Trinity, Schaeffer uses the phrase “When we accept Christ as Savior” and then describes some things that follow it. That phrase “accept Christ as Savior” is a comfortable phrase for evangelicals and also a clear central point to emphasize for unbelievers. If one of Schaeffer’s innumerable conversations took a sudden turn in the direction of immediate personal application, Schaeffer was never far from the direct presentation of the gospel: accept Christ as Savior. If someone asked him in real earnest, What must I do to be saved? he would not lead them on a twisting dialectic through the innards and gizzards of sacred and secular thought: he would say “accept Christ as Savior.” That’s the simplicity.

But Schaeffer also brought the depth: look at the second half of any of his “accept Christ” sentences:

“Now that we have accepted Christ as our Savior, God the Father is our Father.”24

“When we accept Christ as our Savior, we are immediately in a new relationship with God the Father. ...But,of course,if this is so, we should be experiencing in this life the Father’s fatherliness.”25

“When I accepted Christ as my Savior, when my guilt was gone, I returned to the place for which I was originally made. Man has a purpose.”26

“When I accept Christ as my Savior, my guilt is gone, I am indwelt by the Holy Spirit, and I am in communication with the Father and the Son, as well as of the Holy Spirit—the entire Trinity.”27

The simplicity (“accept Christ”) leads into the depth (“I am in communication with the Father and the Son, as well as of the Holy Spirit—the entire Trinity.”) This depth is the spiritual reality that Schaeffer heard young people lamenting the absence of; it is the depth he was missing in 1951 when he called everything to a halt and reevaluated his status as a believer. “It is a moment-by-moment, increasing, experiential relationship to Christ and to the whole Trinity. We are to be in a relationship with the whole Trinity. The doors are open now: the intellectual doors, and also the doors to reality.”28

Remember that at that time he asked God, “But then where is the spiritual reality, Lord, among most of that which calls itself orthodoxy?” And Schaeffer didn’t get a thunderbolt from the sky, or a special revelation, or a second work of grace, or a Pentecostal baptism in the Spirit, or a new revelation that nobody else had ever heard. No, his experience was in fact an insight into what was already his: “Gradually I found something. I found something that I had not been taught, a simple thing but profound. I discovered the meaning of the work of Christ, the meaning of the blood of Christ, moment by moment in our lives after we are Christians—the moment-by-moment work of the whole Trinity in our lives because as Christians we are indwelt by the Holy Spirit. That is true spirituality.”29

That was Schaeffer’s Trinitarianism: always poised between the simplicity and the depth, able to draw from each as he or his audience required, he presented the deeper experience of the Trinity as an invitation to come and live out what all Christians implicitly believe: “It is . . . possible to be a Christian and yet not take advantage of what our vital relationship with the three persons of the Trinity should mean in living a Christian life. We must first intellectually realize the fact of our vital relationship with the triune God and then in faith begin to act upon that realization.”

EXPERIENCING FATHER, SON, AND HOLY SPIRIT

Schaeffer’s encounter with the Trinity, like Nicky Cruz’s and the others we have seen so far, was a definite experience, a breakthrough in his life. But it is important to avoid the trap of reducing his new encounter with the Trinity to the category of experience. When evangelical Christians come to understand the Trinitarian soteriology we have been describing in this book, they tend to describe it as a moment of insight that changes everything about their life and faith. At the very least, they see it as a breakthrough to a new level of depth in the things they had known before. But there are some good reasons for avoiding the category of experience when talking about these great Trinitarian themes.

First, if we were to begin talking about “having a Trinitarian experience” or beginning to “experience the Trinity,” it would sound like a new step to take, a next step in a sequence of steps. But that would be to focus attention in the wrong place. All these Trinitarian realities we have been exploring are contained within the good news of salvation and are already true about the gospel, whether we know and understand them or not (or, as we said earlier, whether we know that we know them or not). The evangelical Trinitarianism we have been describing in the last few chapters is not primarily an advance in experience but in insight. It changes everything, not by introducing you into something that was not previously true but by showing you the significance of something that has been true all along. Salvation is Trinitarian, whether you know it or not; breakthroughs can happen when you move from not knowing to knowing.

No doubt when we do come to see the Trinitarian depth underlying the gospel, we do go on to have an experience. The progress in understanding brings about a fresh encounter with God and an experience with him. But the second reason to be cautious about calling it an experience is that the category of experience is such a sticky one. An experience is a kind of virtual reality, whether the thing that provoked it was real or not. An experience of something is itself something; but a different something than the original something. As a result, experiences can be sticky like flypaper, stopping us at a certain level and not letting us go on to the thing itself. Evangelicals, who have a genius for cultivating authentic experience, also have a knack for reducing things to the level of experience.

Third, experience is too small a category for what we have described here. The Trinity simply cannot fit into the little experiences we are capable of having, with the biographical and psychological limits they impose. There is something incongruous about pointing to a moment in our lives and saying the eternal Trinity is there, as if God could be found within that moment analytically. Our little conversions, awakenings, and renewals simply cannot bear the burden of being the place where God is to be known in his majesty as Father, Son, and Spirit. When God makes himself known, he puts himself into the economy of salvation, not into our experience. The infinite God is present in the vast and comprehensive economy of salvation, to show himself and save us. With our little lives and their experiences, we fit into a subsection of that economy, and God’s glory comes through to us in ways that fit our limited capacities.

The evangelical writers who have insisted on this most vehemently are precisely the ones who have testified to the greatest experiences with God. The more profoundly they have experienced the Trinitarian depths of God’s salvation, the more careful they have been to insist that God is bigger than their experiences of him. Oswald Chambers is a good case in point. He warned, “As Christian workers we must never forget that salvation is God’s thought, not man’s; therefore it is an unfathomable abyss. Salvation is not an experience; experience is only a gateway by which salvation comes into our conscious lives. We have to preach the great thought of God behind the experience.”30 Chambers wrote like this because he was jealous to keep the experience of the gospel from turning into the gospel of experience, which is not good news after all. But he also insisted that what we experience in our lives is a real glimpse of God’s great work. He compared our experiences to a pinhole through which a vast landscape is seen: “When a soul comes face to face with God, the eternal Redemption of the Lord Jesus is concentrated in that little microcosm of an individual life, and through the pinhole of that one life other people can see the whole landscape of God’s purpose.”31

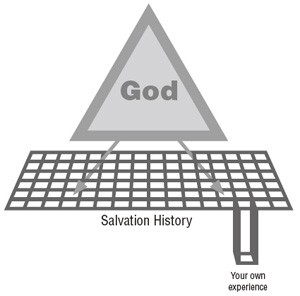

Perhaps we can also make the point about experience by using another familiar evangelical teaching aid:

What we have learned about the kind of evangelical Trinitarianism that changes everything is that God’s own eternal being as the Trinity is what matters most; it is the one thing better than the good news. But the good news, God’s free choice to be himself for us by sending the Son and the Spirit into the economy of revelation and salvation, is the crucial link between who God is and what he does to save us. We find our places within that economy of salvation, and our experience of God in the gospel also comes along for the ride. This is the proper order of evangelical talk about the Trinity and the gospel. It should always be at least implicitly observed, and sometimes that order should be made explicit.

THREEFOLD ASSURANCE

As we learn to order our understanding of Trinitarian salvation, there are many advantages for evangelical thought. One of the greatest is the way the difficult doctrine of the assurance of salvation can find its proper home. The doctrine of assurance can be slippery. Even among those Protestant evangelical traditions that have recognized the necessity of formulating a doctrine of assurance that answers to the biblical witness about faith’s confidence, there has long been a candid acknowledgment that the doctrine must simultaneously face opposite directions. It must assure me that I, even I, am saved; but it must do this by pointing away from me to an objective ground. To state the doctrine too objectively is to leave the believer as an onlooker to a redemptive spectacle that assures him with absolute confidence that somebody is saved but leaves open, disturbingly open, the question whether he is that somebody. To state the doctrine too subjectively, however, directs the believer’s attention to phenomena of his own biography, experience, and consciousness, where the ground of salvation cannot be seen. A well-ordered doctrine of assurance must underwrite the confident confession that even though I am condemned if considered in myself, I am not in fact in myself but in Christ, where I, truly I, am saved.

In a flourishing Christian life, this confident repose on God shows itself as an effortless and un-self-conscious equipoise: gazing on the Savior and glancing at the self, the believer is saved and assured of being saved in one simple motion. Let the redeemed of the Lord say so! But when a Christian begins to lose confidence in salvation, the idea of assurance becomes an idea without a home. In the next few pages, I will show that assurance has a home in the Trinitarian salvation we have been exploring. This is one of the most difficult parts of the book, and some readers may want to skim over it on their way to the Bible and prayer chapters. But others who are troubled about assurance of salvation can find a new and helpful way of thinking about assurance in light of the Trinity.

To many theologians it has seemed that assurance of salvation is best described as assurance of faith and therefore should be included in the description of faith itself, since to have assurance is just to know that one believes the promise of someone worth believing in. On this analysis, assurance is faith roused to self-consciousness, or faith knowing itself as faith. This answer is surely correct, so long as it can be consistently distinguished from a confidence in the exercise of faith, or the felt experience of having faith. When assurance is considered as a kind of intensification of faith or as a subjective reflex of the act of faith, it is too easily assimilated to the risings and fallings of religious experience and subject to all the temperamental vicissitudes of that experience. The summons to assurance then becomes an exhortation to grasp the promise of salvation with a passionate inwardness that is the measure of faith.

In reaction to this, some theologians bundle assurance and faith together and then link them to an external source of authority. One obvious external source is the authority of the church, especially its competence to deliver truthful doctrines and valid sacraments. Faith and its assurance then quickly become reduced to implicit faith in the church’s authority. Much medieval religion, however correct in substance it may have been, relied too heavily on believing whatever the church taught, even without knowing what that was. Calvin rightly ridiculed this as “ignorance blended with humility,” a mixture unworthy of the name of faith.

Another possibility is the appeal to biblical authority to ground assurance. Since Scripture is the record of God’s promise, it is certainly right to appeal to it in this way. But in a way that is structurally similar to the appeal to church authority, the appeal to the authority of Scripture is only as successful as salvation it specifies. Unless that content is made explicit, the appeal to the divine authority of Scripture is a mere placeholder marking out where the argument should go.

These three attempts are variations on the theme of grounding assurance in an intensification of faith: first in the intensified experience of faith, second in the authority of the church that proposes what to believe, and third in the Scriptures as the authoritative record of God’s promises that are to be believed. We might label these three solutions in their pure forms as the pietist, the Catholic, and the fundamentalist solutions. None of them is entirely mistaken, but they have in common a tendency to leave the content of the promise unstated. On their own they end by collapsing into either the objective or subjective ranges of the spectrum.

A heroic effort to ground assurance in God’s eternal predestinating election is characteristic of the Reformed theological tradition. This has many merits to recommend it. First, it marks a definite advance by naming the content of salvation: God’s gracious election. Second, it recognizes the requirement for a truly objective starting point for assurance: you don’t get much more objective than monergistic predestination! But precisely in this success, it leaves open too much space between the objective and subjective poles of assurance. The question of assurance— How can I know that I am saved?—is not so much resolved as restated in the famous form: How can I know that I am among the elect? This bluntness is no help in the search for assurance.

The best Reformed thinkers, in contrast, have always kept their explorations of election within the wider framework of adoption, indwelling, and an effectual call worked out in the course of history, along with a full enjoyment of the manifold benefits of union with Christ. Reformed soteriology has proven its capacity for a great inclusiveness of multiple biblical themes.

The classic Protestant view of assurance, however, emphasizes justification. “I should be assured of my salvation because God has unilaterally, forensically justified me in pronouncing me righteous on the grounds of Christ’s redeeming work.” As a proposed doctrinal home for assurance, justification is very promising: it is biblically well attested, it is highly objective, and it is specific about what salvation is. In its specificity it is sharply focused and served as a perfect point of conflict with the Roman Catholic theology that denied assurance of salvation. The Reformers rightly identified justification as the right place to draw the line, and assurance followed in its train.

However, this great virtue of the Reformation account of justification carries a particular disadvantage when it comes to its application to the doctrine of assurance: it is a focusing maneuver, specifying in the most precise and pointed way the element of salvation on which everything turns. That is appropriate for a dispute over the nature of God’s mighty act of justifying the ungodly and the surgical work of excising the overgrown claims of human merit within salvation. But it is less helpful for the doctrine of assurance, because the movement of thought required for describing assurance is not the movement of focusing but the expansive and inclusive sweep of reciting the many blessings of salvation. As we have already seen, the Trinitarian account of salvation is able to deliver that expansiveness and inclusiveness. That makes Trinitarianism the natural home for the doctrine of assurance. Some of the benefits of locating assurance within this explicitly Trinitarian context include the following.

First, it ensures a greater objectivity than any other option. Back behind the economic sending of the Son and the Spirit, though in line with them, is the eternal immanent Trinity. The way this soteriology directs our attention to God’s absolute aseity, independence, and blessedness is unprecedented. And it does so without some of the distorting consequences of appealing first to God’s inscrutable sovereignty in election. It gets behind even that eternal counsel to the only thing behind the eternal counsel, the very bedrock of the being of God: his being as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Second, it takes the encounter between the believer and Jesus and puts it in the broader context of the Father, Son, and Spirit acting concertedly for each other’s glory, and then as a subordinate end, for our salvation. While a confession of the encounter between Jesus and me is integral to evangelical faith, it must happen against the horizon of Jesus and his Father. Trinitarian salvation is intensely personal but allows us to construe the word personal as an indication of the infinite depth of the divine life rather than as a pointer to our richly developed inwardness in its religious manifestation. It enables believers to respond with proper gratitude to God’s action on our behalf, without degenerating into a monotonously self-referential and inwardly focused piety.

Third, this Trinitarian view of salvation is routed through the economy of salvation and moves from God to salvation history before contacting me and my own experience of salvation. This requires me to see my Christian experience as serving God’s larger ends, employing me as a witness to God’s spreading glory. The economic presences of the Son and the Spirit are, after all, missions, a word that was first of all a technical term in Trinitarian theology before it was a description of cross-cultural world evangelism. Our participation in the twofold mission of the Son and the Spirit is not only our salvation but our employment in the mission of God.

Finally, an explicitly and elaborately Trinitarian soteriology commends itself as a hospitable location for the doctrine of assurance in that robust confidence in God and his salvation flourish there. The reason for this is that, as we have seen, the Trinity is the gospel. Trinity and gospel are not just connected in some distant way, as two ideas that can be related to each other by a long train of reasoning. The connection is much more immediate than that. Seeing how closely these two go together depends on seeing both Trinity and gospel as clearly as possible in a large enough perspective to discern their overall forms. When the outlines of both are clear, we should experience the shock of recognition: Trinity and gospel have the same shape! This is because the good news of salvation is ultimately that God opens his Trinitarian life to us. Every other blessing is either a preparation for that or a result of it, but the thing itself is God’s graciously taking us into the fellowship of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to be our salvation.

Trinitarian salvation, then, is the proper home for the assurance of salvation. American Presbyterian theologian Benjamin Morgan Palmer’s excellent little book The Threefold Communion and the Threefold Assurance drew these connections in a powerful way:

What amazing security does this view give to the whole system of grace, seeing that it cannot fail in a single point except through a schism in the Godhead itself. The hand trembles that writes the daring suggestion; which is only saved from blasphemy by the assurance that he who searches the heart knows it is written only to give the most intense emphasis to the truth which it declares.

Palmer goes on: “Well may the Psalmist of old sweep with his fingers the strings of the Hebrew lyre to the tune of the sixty-second Psalm (vs. 6, 7): ‘He only is my rock and my salvation: he is my defence; I shall not be greatly moved. In God is my salvation and my glory; the rock of my strength and my refuge is in God.’”

Marcus Rainsford, the interlocutor with Moody in the Gospel Dialogues, was also alert to the benefits of the Trinitarian background for the doctrine of assurance. He said:

This is precious truth,but it stands upon a rock.The Father has as much interest in the salvation of the redeemed as Christ has, and Christ and the Holy Ghost have as much interest in them as the Father has.The Father’s love gave Christ to them, Christ’s love gave Himself for them, and the Holy Ghost’s love reveals and applies to them the salvation of God. 32

And he made the same point again in an equally Trinitarian way:

We are taught in Scripture that our security flows from three great facts.The Father has loved us with an everlasting love—a love that never changes; Christ, who died for our sins, is now at God’s right hand in resurrection glory and ever lives to make intercession for us, pleading His work finished and accepted; and God the Holy Ghost dwelleth in us.33