PAUPERS, VAGRANTS AND LUNATICS

PAUPERS

As the population expanded during the sixteenth century, so did poverty. Increasing numbers of vagrants alarmed governments: poverty, vagrancy, masterlessness and landlessness all seemed to threaten the social order. And the abolition of monasteries and chantries, which had previously offered some relief to the poor, did not help.

I don’t give to idlers.

The Poor Law Acts of 1597 and 1601 provided the official remedy for over two centuries. Under them, parish overseers provided work, relieved the impotent, bound pauper children as apprentices and levied parochial poor rates when necessary. Churchwardens were ex officio overseers. The records of overseers are parish records.1

Justices of the Peace appointed overseers on the nomination of parish vestries, examined their accounts and supervised their work. Between 1597 and 1834, this task occupied much of their time. They adjudicated disputes between paupers and overseers, between overseers and ratepayers, and between parishes. Justices had to be careful: paupers knew what their legal rights were, and did everything they could to exert them. The paupers of Potterne (Wiltshire), ‘a very discontented and turbulent race’, even clubbed together to purchase a copy of Burn’s Justice of the Peace and Parish Officer, to inform themselves of their entitlements.2

Justices could grant habitation orders, requiring overseers to provide the poor with accommodation. They determined places of settlement, made removal orders, authorised the binding of pauper apprentices and conducted bastardy examinations to determine the parentage of bastards. Bastardy orders made by Justices required fathers to pay maintenance, either to the mother or to the overseers, until the child reached the age of seven, that is, until he could be apprenticed. Bastards’ parents – especially their mothers – were frequently whipped.

The Elizabethan system, in its essentials, lasted for more than two centuries. When it was replaced in 1834, Justices continued to have some responsibilities. They served as guardians in the new Unions, continued to determine settlement, approved rates, adjudicated over emergency relief and settled disputes. Pauper lunatics (see below) continued to be admitted to asylums under Justices’ control. Nevertheless, the 1834 Act contributed to the erosion of Justices’ powers which we have already seen in the courts, and which also followed the introduction of professional policing.

The Elizabethan Acts provided that paupers were to receive relief from the parish in which they were ‘settled’. Broadly, they could claim settlement by birth, by apprenticeship, by service for more than one year, by serving as a parish officer or by having paid rates on property valued at more than £10. The concept of ‘settlement’ received ever more precise definition after the 1662 Act of Settlement, and led to numerous disputes between parishes. The law of settlement has been described as ‘that monstrous entanglement of statutes, amendments, and judgments … which … brought so much grist to the mill of the country attorney’.3

Justices’ involvement in the process began when two of them examined paupers (or sometimes merely those thought likely to be paupers in future) to determine their settlement. Settlement examinations record the information given. They provide somewhat biased mini-biographies. Paupers’ movements since they last gained settlements are recorded, but examinations ignore details irrelevant to their purpose. They may record names, ages, places of birth, details of parents, wives, children, and former masters, former places of residence and details of any apprenticeships served.

Once settlement had been determined, a removal order could be issued. These might be written on the backs of settlement examinations, although sometimes printed forms were used. They were usually acted upon immediately, and should have been signed by the constable of each parish through which the pauper passed. They give personal details of paupers, perhaps including names of wives and children. Examinees who were not actually claiming relief could obtain a settlement certificate from their home parish. These certificates acknowledged that parish’s liability to pay relief if needed, and enabled its holder to avoid removal.

Settlement examinations, removal orders and settlement certificates, were generally kept in parish chests, either of the parish which secured removal, or of the parish of settlement. The latter, however, frequently appealed against removal orders which imposed a liability on them. Between 1700 and 1749, there were 581 appeals to the North Riding Quarter Sessions.4 Quarter Sessions order books are full of decisions on such cases. Related settlement examinations and removal orders can frequently be found amongst Quarter Sessions records.

On arrival in his parish of settlement, the pauper was entitled to claim relief, including the provision of housing, food, fuel and/or clothing. Justices were expected to ensure relief was provided; paupers frequently appealed to Justices against overseers’ decisions.

Justices also oversaw the apprenticing of pauper children. Apprenticeship was a respectable institution; it provided for the training of young men in a trade which would enable them to obtain a reasonable livelihood. Private apprentices normally spent seven years living in their masters’ household whilst they learnt their trade; their parents sometimes paid substantial premiums to masters who could provide good training. Pauper apprenticeship was a perversion of this system; it provided a means by which overseers could exercise social control over the most volatile section of the community, and, at the same time, considerably reduce the impact of paupers on the poor rates. Overseers bound boys until they attained the age of 24 (reduced to 21 in 1778), without reference to their parents. Girls served until age 21 or marriage. Overseers could require masters in their own parish to accept parish apprentices, or could pay a small premium to masters outside of their parish. The cost of supporting pauper children was thus passed to their masters. The trades to which paupers were apprenticed were of low status – perhaps husbandry, or, for girls, housewifery – and frequently constituted mere drudgery. Sometimes, training was minimal. The terms of apprenticeship were recorded in pauper apprenticeship indentures, which overseers frequently retained in the parish chest.

Justices supervised apprenticeship. Apprenticeship disputes – both private and pauper – were amongst the commonest cases to come before individual justices. Edmund Tew‘s justicing book is full of references to them.5 So are Quarter Sessions order books. Justices adjudicated complaints raised by both masters and apprentices, fined masters who refused to accept pauper apprentices, and punished apprentices who absconded. Masters needed Justices’ approval to dismiss an apprentice, or to ‘turn him over’ to a new master. Justices re-assigned apprentices whose masters had died, been imprisoned for debt or gone out of business.

From 1802, Justices’ assent to pauper bindings were recorded in registers of pauper apprentices kept by overseers. The Parish Apprentices Act of 1816 required Justices ‘to enquire into the propriety of binding such child apprentices to the person or persons to whom it shall be proposed by … overseers to bind such child’; they had to sign a binding order, which was attached to the indenture.

The Elizabethan Poor Law was replaced by the New Poor Law Act in 1834. It merged many parishes into Poor Law Unions, governed by elected Boards of Guardians responsible to the central Poor Law Commissioners, not to Quarter Sessions. Unions were abolished in 1929. Their records are not county records, and are consequently outside of the scope of this book.

Further Reading

For good general introductions to the history of the Poor Law, see:

• Hindle, Steve. On the Parish? The Micro-politics of Poor Relief in Rural England c1550-1750. (Clarendon Press, 2004).

• Lees, Lynn Hollen. The Solidarities of Strangers: The English Poor Laws and the People, 1700-1948. (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

On the law of settlement, see:

• Taylor, J.S. Poverty, Migration and Settlement in the Industrial Revolution: Sojourner’s Narratives. (Society for the Promotion of Science and Scholarship, 1989).

Basic introductions to Poor Law records are provided by:

• Fowler, Simon. Poor Law Records for Family Historians. (Family History Partnership, 2011).

• Cole, Anne. Poor Law Documents before 1834. (2nd ed. Federation of Family History Societies, 2000).

For a more detailed guide, see:

• Burlison, Robert. Tracing Your Pauper Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians. (Pen & Sword, 2009).

Many facsimiles of Poor Law documents are printed in:

• Hawkings, David T. Pauper Ancestors: A Guide to the Records Created by the Poor Laws in England and Wales. (History Press, 2011).

Guides to settlement papers and overseers’ accounts are included in:

• Thompson, K.M. Short Guides to Records. Second Series Guides 25-48. (Historical Association, 1997).

For a detailed guide to apprenticeship records (including pauper indentures), see:

• Raymond, Stuart A. My Ancestor was an Apprentice: How Can I Find Out More about Him? (Society of Genealogists, 2010).

• King, Steven. ‘Pauper letters as a source’, Family & Community History 10(2), 2007, pp.167–70.

• Levene, Alysa et al., eds. Narratives of the Poor in Eighteenth-century Britain. Vol. 1: Voices of the Poor: Poor Law Depositions and Letters. (Routledge, 2006).

The minutes of Poor Law Union guardians are described by:

• Coleman, Jane M. ‘Guardians minute books’, in Munby, Lionel M., ed. Short Guides to Records. (Historical Association, 1972, separately paginated).

An extensive listing of surviving union records is included in:

• Gibson, Jeremy, et al. Poor Law Union Records. (2nd/3rd eds. 4 vols.

Federation of Family History Societies/Family History Partnership, 1997–2014).

A historical account of every workhouse, together with much other valuable information, is provided by:

• The Workhouse

www.workhouses.org.uk/

See also:

• Reid, Andy. The Union Workhouse: A Study Guide for Teachers and Local Historians. (Phillimore, for the British Association for Local History, 1994).

Essex

• Sokoll, Thomas, ed. Essex Pauper Letters, 1731-1837. (Records of Social and Economic History, new series 30. Oxford University Press, 2001).

Gloucestershire

• Gray, Irvine, ed. Cheltenham Settlement Examinations, 1815-1826. (Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Records Section 7, 1969).

• Willis, Arthur J., ed. Winchester Settlement Papers 1667-1842, from Records of several Winchester Parishes. (The author, 1967).

Lancashire

• Hindle, G. B. Provision for the Relief of the Poor in Manchester 1754-1826. (Chetham Society 3rd series 23, 1976). Useful bibliography.

Middlesex

• Hitchcock, Tim, & Black, John, eds. Chelsea Settlement and Bastardy Examinations, 1733-1766. (London Record Society 33, 1999).

Sussex

• Pilbeam, Norma, & Nelson, Ian, eds. Poor Law Records of Mid-Sussex 1601-1835. (Sussex Record Society 83, 1999).

Wiltshire

• Hembry, Phyllis, ed. Calendar of Bradford on Avon Settlement Examinations and Removal Orders 1725-98. (Wiltshire Record Society 46, 1990).

VAGRANTS

Vagrancy was another important issue for the Justices, especially in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Vagrants were defined as poor, able-bodied men and women without employment or fixed abode. The law required them to find masters or face punishment. The government viewed the problem of vagrancy very seriously. In late sixteenth-century Warwick, the main judicial business was vagrancy. Between 1631 and 1639, there were almost 25,000 convictions for the crime of vagabondage.6 The role of Provost Marshalls in dealing with vagrants was noted in Chapter 6.

The term ‘vagrant’ was very imprecise, and meant whatever an individual Justice wanted it to mean. Many were charged with deserting or failing to maintain their families. Prostitutes could be charged as vagrants, although prostitution itself was not illegal. Servants who absconded from their masters were regarded as vagrants. Other minor crimes frequently resulted in a charge of vagrancy, since prosecution was much easier: individual Justices had summary jurisdiction and no jury was required. Justices could order a whipping or incarceration in the House of Correction. A charge of vagrancy could also mitigate the sentence that a more serious charge might incur. Conversely, some suspects committed as vagrants were subsequently found guilty on different charges.

Legally, paupers and vagrants were distinct, although in practice they were frequently identical. They were dealt with by parish officers, and their treatment became increasingly similar. The Vagrant Removal Cost Act of 1700 removed the costs of vagrant administration from parishes to counties, and had the unintentional effect of encouraging parishes to treat paupers (for whom they were liable) as vagrants. Parishes were thus enabled to reduce their costs.

Prejudice against itinerants amongst the settled population was strong; they were feared. Justices could grant passes to itinerants such as soldiers returning from wars (for whom no other provision was made), shipwrecked mariners or poor students travelling to or from University. Effectively, these were licences to beg, and were frequently counterfeited. Not all vagrants had a pass, and punishment for vagrancy could be harsh. Conviction might mean a whipping, and mutilation of one’s ear. A third conviction was a felony, subject to hanging. Incarceration in either a prison or a House of Correction was frequent, as was impressment into the army or Royal Navy.

Whipping at the cart’s tail, from Mark Twain’s The Prince and the Pauper.

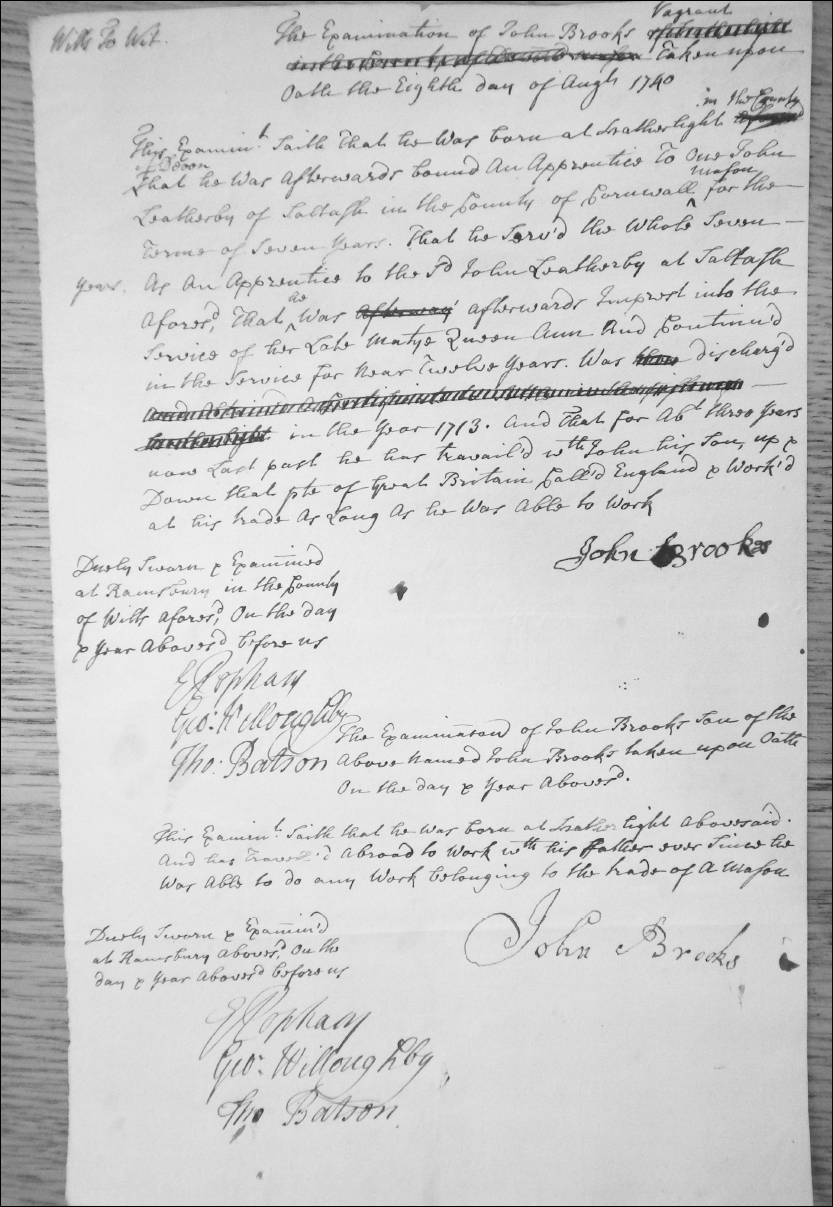

The vagrant examination of John Brooks. (Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre A1/330.)

Once punishment had been inflicted, vagrants were ‘passed’ to their parish of ‘settlement’, accompanied by constables. Between 1700 and 1739 separate rates were sometimes levied to pay for passing. Vagrants’ passes were similar to pauper removal orders, but were directed to constables, rather than to overseers and churchwardens.

Documentation of vagrancy improved in the early eighteenth century, largely as a result of the Act of 1700 mentioned above, and of the Vagrant Act of 1714. The latter required Justices to record examinations of vagrants in duplicate, to lodge one copy with the Clerk of the Peace, and to either make a warrant for committal to the House of Correction, or issue a pass to convey the vagrant to his/her parish of settlement. Passes could only be issued after examination, and after a whipping (although many Justices ignored the latter). Parish constables received certificates specifying the mode of travel, and the route, and returned them with their claims for expenses to county Treasurers. Their claims listed vagrants conveyed, the routes used, and expenses such as subsistence costs for sick vagrants, burial and lying in costs, horse hire and charges for guards. Some counties appointed contractors to undertake the work; their expenses were similarly detailed.

Further Reading

For early modern vagrants, see:

• Beier, A.L. Masterless Men: the Vagrancy Problem in England 1560-1642. (Methuen, 1985).

Eighteenth-century vagrancy is considered in:

• Eccles, Audrey. Vagrancy in Law and Practice under the Old Poor Law. (Ashgate, 2012).

An Act of 1714 authorised Justices of the Peace to commit persons ‘of little or no estates, who, by lunacy or otherwise are furiously mad, and dangerous to be permitted to go abroad’. This was re-enacted in 1744. These Acts probably codified existing practice. Pauper lunatics could be confined in workhouses, or in Houses of Correction. An 1807 enquiry counted 2,398 pauper lunatics; 1,765 were in workhouses, 113 in Houses of Correction. Presumably the rest stayed with their families.7

Better provision was authorised by the County Asylums Act of 1808. The first asylum under this Act was opened in Nottinghamshire in 1812. Provision was not, however, compulsory, and Kent’s first asylum was not opened until 1833. It was not until 1845 that Justices were required to build asylums, which were to be subjected to regular Home Office inspection. Essex opened its first asylum in 1853.

An eighteenth-century lunatic asylum. (Courtesy of Wellcome Images.)

Admittance to county asylums was authorised by a Justice on application by a parish overseer, or, after 1834, a Union relieving officer. Magisterial control over admittances continued until as late as 1959, subject to various checks from professionals. From 1845, when a medical officer or a constable became aware of a pauper lunatic, he had to notify the relieving officer within three days. He, in turn, brought the lunatic before a Justice of the Peace within three days. Union medical officers signed applications for admission after 1853. Justices had discretion over admittances, and could admit lunatics who had come to their notice in other ways – as when David Perkins heaved a brick through a Leicestershire Justice’s window in 1851!8 After 1853, if a patient had certificates from both the medical officer and an independent doctor, he or she had to be admitted.

County asylums were almost completely ignored by the 1834 Poor Law Act, remaining under the control of Quarter Sessions. Provision was insufficient to keep up with demand; asylums rapidly became overcrowded. Some pauper lunatics stayed in workhouses; others were returned there from overcrowded asylums. Union medical officers, under an 1862 Act, could determine whether a lunatic was ‘a proper person to be kept in a workhouse’.

By Acts of 1815 and 1828, parish overseers were required to make returns of pauper lunatics to Clerks of the Peace. These state patients’ names, ages, how long they had been ill, and the cost of their maintenance. After 1842, similar returns were made by the clerks of Poor Law Unions to the Poor Law Commissioners; these are now in The National Archives, series MH 12, and selected records can be downloaded.

County asylum records include papers relating to their establishment and maintenance. Quarter Sessions appointed Visitors, whose minutes and reports may be available. So may admission registers, case books, reports from medical officers, personnel records, registers of deaths and burials, title deeds, and a variety of other documents. The records of Lancaster Asylum include committal warrants, 1816–63, and a diet book for 1883–9. Asylums had to make returns of patients under the 1815 Act. After 1845, copies of admission registers of both public and private asylums had to be sent to the Lunacy Commission; they are now in The National Archives, series MH 94, and are digitised at http://search.ancestry.co.uk/search/db.aspx?dbid=9051; The Commissioners also received information on asylum building plans, now in series MH 83. The Report of the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy to the Lord Chancellor (1844) is a detailed account of the condition of every asylum in England and Wales.9

Admission documents may prove particularly useful to researchers for biographical purposes. Their content was prescribed under Acts of 1845 and 1853. Justices had to certify that the patient was a proper candidate for admission to the Asylum. They did, however, have to be convinced by both relieving officers and medical officers, who both provided much useful information.

Asylum case books were not prescribed by legislation until 1845, but were frequently kept. The printed case books for Leicestershire provided space for entering basic personal information, plus various medical questions with spaces for answers.10

Justices also had responsibilities towards lunatics who were not paupers. The Madhouses’ Act of 1774 (and a subsequent Act of 1832) required Quarter Sessions to licence private asylums; Justices were to be appointed as visitors, except in London, where this role was performed by the College of Physicians. Admittance required certification by a physician, surgeon, or apothecary. Names of inmates were certified to the College of Physicians until 1828, and to the Home Secretary until 1845 (although records cannot now be traced). Prior to the Asylum Act of 1845, there were generally more pauper inmates than private patients. Paupers were not, however, admitted if there was room for them in a county asylum. An 1815 Act permitted private patients to be admitted to county asylums if there was space. Further regulations were introduced by Acts of 1828 and 1845.

Applications for madhouse licences, plans of buildings, registers of admissions, visitors’ report books and other records may survive amongst Quarter Sessions archives. Annual reports and minutes of visitors may also be found. A register of private asylums for 1798–1812, with the names of patients admitted, is in The National Archives, MH 51/735. Records from various private asylums are currently being digitised by the Wellcome Library (http://wellcomelibrary.org/collections/digital-collections/mental-healthcare). The records of many asylums, both public and private, are listed in the Hospital Records Database (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/hospitalrecords).

The best introduction to the history of madness is:

• Scull, Andrew. The Most Solitary of Afflictions: Madness and Society in Britain, 1700-1900. (Yale University Press, 1993).

See also:

• Bartlett, Peter. The Poor Law of Lunacy: the Administration of Pauper Lunatics in mid-nineteenth-century England. (Leicester University Press, 1999).

• Smith, Leonard D. Cure, Comfort and Safe Custody: Public Lunatic Asylums in early nineteenth-century England. (Leicester University Press, 1999).

A detailed guide to lunatic records is provided by:

• Chater, Kathy. My Ancestor was a Lunatic. (Society of Genealogists Enterprises, 2015).