ASSIZES

Twice a year, every county in England (except London, Middlesex, Cheshire, Durham and Lancashire) was visited by Assize judges. Between 1543 and 1830, the Court of Great Sessions performed a similar function in Wales.1 Judges’ names are listed by Cockburn for the period 1558–1714.2 The judges served as the eyes and ears of the Crown, supervising the activities of Quarter Sessions, and adjudicating in difficult or serious cases. James I instructed his judges to:

Remember that when you go your circuits, you go not only to punish and prevent offences, but you are to take care for the good government in general of the parts where you travel … you have charges to give to justices of peace, that they do their duties when you are absent, as well as present: take an account of them, and report their service to me at your return.3

The Westminster judges, drawn from the courts of King’s Bench, Common Pleas and the Exchequer, sitting as the General Eyre, were first sent on circuit in the late twelfth century. The Eyre courts are outside of the scope of this book; for a general introduction to their records, see David Crook’s Records of the General Eyre (HMSO, 1982).4 Assizes succeeded the Eyre in the fourteenth century.

For the average litigant, the Assizes ‘assumed the awful remoteness of a divine visitation’.5 Hannah More likened the deity to an English judge, describing the Day of Judgment as the ‘Grand Assizes or general gaol delivery’. More widely, the purpose of Assizes (and of the courts generally), before the eighteenth century, was not the pursuit of an abstract concept of justice, but rather the preservation of social order and harmony by a personal and judicious application of State coercion. The court was theatre, emphasising the majesty of the law, the awfulness of possible judgements, and the mercifulness of the judge. The law was intentionally harsh, so that its application could be mitigated by (variable) mercy. Judgement depended as much on the circumstances of the offender as with whether they had actually offended. Was the accused entitled to merciful treatment?

Winchester Great Hall, meeting place for Hampshire Assizes and Quarter Sessions.

Attitudes changed in the late eighteenth century. Certainty of punishment began to be seen as the greatest deterrent; discretionary application of the law was regarded as weakening its effects. It was thought that punishments ought to be clearly defined, and less discretion allowed to the judges. Sentencing options changed too.

The local elite relied heavily on the Assize judges. Quarter Sessions referred to them all their difficult cases, and most felonies. The judges provided valuable legal advice, reinforced Justice’s authority in setting rates, and provided an informal arbitration service. Assiduous Clerks of the Peace recorded their significant rulings in Quarter Sessions order books, for future reference; many Justices of the Peace similarly recorded them in their own commonplace books.

The Bloody Assizes. Judge Jeffreys denouncing the Monmouth rebels.

Assizes judges were named in Commissions of the Peace, and sometimes sat as equals with Justices of the Peace. Their powers, however, were much wider. For example, they had authority over borough Quarter Sessions and over neighbouring counties, where others in the Commission could not adjudicate. Professional judges were first sent on Assize circuits in 1273. Fourteenth-century statutes gave them criminal jurisdiction, which they exercised until 1972, and supervisory powers over Sheriffs and other officers. As the powers of Justices of the Peace increased, so did the powers of Assize judges to supervise their activities.

Court administration was in the hands of Clerks of Assize, who were remunerated mainly by fees levied on litigants. Originally, they were probably the judges’ private clerks. By the sixteenth century, Clerks had their own staff. These might include the bailiff, one or two clerks, the crier and the marshall. The latter two were appointed by the judges, and levied their own fees. The crier announced each stage of proceedings, the marshall kept order in court, and the bailiff brought the accused, together with prosecutor and witnesses, before the court. Clerks of Assize have been described as ‘a compact and highly professional body’.6 In The office of the Clerk of Assize… together with the office of Clerk of the Peace (1682) they had an extensive handbook for their work. Cockburn has listed clerks and associate clerks for the period 1558–1714.7

Assizes were held under Commissions issued by the Crown Office in Chancery. The Commission of Assize authorised judges to hear civil suits. The hearing of criminal case was authorised by a Commission of Oyer and Terminer, which also commissioned the Clerk of Assize and his associates and leading Justices of the Peace. The Commission of Gaol Delivery authorised the two judges, the Clerk of Assize and his associates, to try the prisoners committed to gaol. Clerks could act for absent judges. Until the sixteenth century, Chancery issued a writ of venire facias to the Sheriff, commanding him to ‘produce’ the Assize at a time and place to be notified by the judges’ precept.

Before they left London, the judges attended Star Chamber to hear a charge from the monarch, or, more usually, the Lord Chancellor. Lord Burghley used his charge in 1598 to emphasise the importance of enclosure, depopulation, vagrancy and poor relief legislation passed by the 1597–8 Parliament. Within three weeks, Assize judges were urging local magistrates to implement these statutes.8 Charles I urged on the judges the necessity of Ship Money in 1628, and the importance of the Book of Orders in 1630.9 From the Crown’s point of view, the prime task of Assize judges was to maintain communication with Quarter Sessions, and to ensure that local officers were acting in the interests of the Crown. Charges delivered to sixteenth and seventeenth century Assize judges, and repeated at Assizes, provide a useful guide to social, economic and political ills.

After the Restoration, charges were usually written. In the eighteenth century, the distinction between executive and judicial decisions began to be recognised; the judges became non-political, and were expected to use their own discretion. Their involvement in administrative matters became routine, and, eventually, defunct.10 The perennial concerns of the Privy Council came to be expressed through printed questions issued to constables prior to Assizes. The former political role of Assize judges was taken over by the Lord Lieutenants. Nevertheless, in 1781 they were instructed to inquire into gaolers’ abuses,11 and they continued to oversee all important business conducted by Quarter Sessions.

Assize procedures began when judges issued precepts to Sheriffs, indicating dates and places for sittings. Sheriffs issued warrants to Hundred Bailiffs for jurors, appointed preachers for Assize sermons, and visited the judges in London (or sent their Under-sheriffs) to discuss the issues likely to arise, taking with them gaol calendars.

Hundred Bailiffs selected jurors, although Sheriffs could intervene. Twenty-four ‘good and lawful men’ were supposed to be impanelled, although the number was not adhered to strictly. From them, the jury could be selected. Jurors were not always impartial: in the sixteenth century, Harrison thought that ‘certes it is a common practice … for the craftier or stronger side to procure and pack such a quest as he himself shall like of’.12 It was not easy for his contemporaries to find sufficient jurymen; in Lambarde’s Kent Grand Juries were largely made up of constables, whose attendance was compulsory.13 Assizes used duplicates of the jury lists produced for Quarter Sessions.14

The verdicts of Assize Grand Juries came to be regarded as the decisive ‘voice’ of the county in political matters. When civil war was breaking out in 1642, it was before them that the rival causes sought approval. After the Restoration, membership acquired greater status; juries were frequently headed by baronets or knights, and consisted mainly of esquires, including many Justices. Such jurors could stand up to Assize judges when they had a mind to do so.

On arrival in the county, judges were met by the Sheriff’s officers, conducted to their lodgings in the Assize town, and greeted by the county gentry. Proceedings began with the Assize sermon.15 Some were long and pedantic, others caused a stir. In 1642, a Kentish Assize sermon led to the arrest of Justice Malet whilst he was sitting in court. He was escorted to the Tower.16 Two centuries later, in 1833, John Keble17 used his Assize sermon to launch the high church Oxford Movement.

The sermon concluded, the judges processed to the Court, and the clerk read the Commissions. The Sheriff returned his precept, putting in the writs of nisi prius which had been directed to him, plus the panel of grand jurors, the nomina ministrorum listing all those required to attend, and the gaol calendar listing prisoners for trial. The latter two were frequently written on a single sheet, although from the mideighteenth century printed calendars became increasingly common. The nomina ministrorum in the seventeenth century usually listed Justices of the Peace, coroners, and the bailiffs of Hundreds and Liberties: constables and borough mayors were generally not included. Absences were noted by a prick as it was called over. Many justices were usually absent – between 1558 and 1625, absenteeism averaged 52 per cent in the Home Circuit.18 Death, illness, old age and absence on legal or Crown business were the usual excuses. Absentees could be fined, at judges’ discretion.

Coroners put in their inquisitions, Justices of the Peace their examinations and informations, Hundred Constables their presentments (given to them by parish constables). The judges themselves brought documents from the Privy Council. Once the documentation had been placed before the court, the Grand Jury, consisting of between thirteen and twenty-three gentlemen, was called and sworn. And one of the judges delivered the charge.

The charge to the Grand Jury, like that at Quarter Sessions, directed them how to proceed, and what offences they should particularly inquire into. Its preamble included the instructions the judges had received in Star Chamber. Eighteenth-century charges became secular sermons, emphasising the blessedness of law and constitution, and the virtues of authority and obedience. By this time, most Justices were well educated, and had little need for detailed instruction in the law, except in the case of new legislation.

CRIMINAL MATTERS

The Grand Jury responded to the charge by presenting the state of the county, and scrutinising the documentation. The court then divided into two. From the mid-sixteenth century, criminal cases were heard by one of the judges; civil cases by the other. Trial procedures were similar to those of Quarter Sessions. Grand jurors could make presentments of offences known to them personally. They reviewed indictments drawn up by the Clerk of Assize from the gaol calendars, or on the instruction of prosecutors. Clerks of the Peace forwarded indictments of casus difficultatis from Quarter Sessions. Coroners’ inquisitions were treated as indictments in cases of homicide.

The Grand Jury, like its counterpart at Quarter Sessions, endorsed indictments either billa vera or ignoramus; the latter were mostly destroyed. Indictments might be amended to reduce the seriousness of crimes, thus mitigating sentences, or enabling the accused to make the fictional plea that they were clergy (see below).

Assizes were increasingly preoccupied with cases of burglary, robbery and grand larceny. Between 1558 and 1714, perhaps 70 per cent of all criminal indictments at Assizes were for larceny and related offences. Homicide indictments rarely occupied more than 10 per cent of the calendar. Indictments for witchcraft totalled perhaps 5 per cent, at least before 1680.19

Most cases heard before Assizes came from Quarter Sessions. Justices of the Peace preferred Assize judges to hear capital cases, although they did have the power to try them. Assizes increasingly heard appeals against Quarter Sessions’ decisions, especially in settlement cases. Increasing business meant that speed was sometimes essential; as late as 1869, Baron Gurney was described as ‘rushing through the [Assize] calendar like a wild elephant through a sugar plantation’.20 Lack of time could force judges to refer cases back to Quarter Sessions. Cases could also be removed from Assizes to King’s Bench by writ of certiorari. Relevant indictments, presentments, and convictions can be found in The National Archives, series KB 9 & 11.

A Candle in the Dark gave members of the judiciary advice on how to deal with ‘witches’.

Little is known about pre-nineteenth century trial procedures, except that they were ‘nasty, brutish and essentially short’.21 The nature of the evidence heard, the influence of judges, the outlook of jurors, and the extent to which the strictness of the law was tempered by mercy, are all difficult to assess. But courts were not dispassionate. The presumption of innocence until found guilty was not a doctrine known until c.1780, and not fully accepted until c.1820. Several cases were tried together, the accused being chained to each other. A petty jury was empanelled, indictments were read in the order they appeared on the gaol calendar, and the accused entered their pleas. The vast majority pleaded not guilty, and indictments were marked po[nit] se. Guilty pleas were discouraged; they meant the judge had no knowledge of circumstances, and was therefore forced to pass judgement without being able to recommend a reprieve.22 Indictments of those pleading guilty were marked cog[novit].

As at Quarter Sessions, prosecutions were mostly undertaken by the victims themselves, probably coordinated by Clerks of Assize. It was not until the 1720s and 1730s that prosecuting lawyers began to appear. The evidence presented in court consisted of the magistrate’s written examination (although this was only read if it constituted evidence for the Crown), occasionally petitions or ‘testimonials’ from the locality, and oral testimony from victims and other witnesses. Confessions, and incriminations by accomplices, carried considerable evidential weight, as did the victim’s evidence. Crown witnesses were called first; if they were poor, they might receive an ex gratia payment. Such assistance was not available for defence witnesses. In cases of felony, defence witnesses were heard, but not sworn.

The accused had to prove his innocence with very little preparation, frequently not knowing the nature of the evidence against him, and finding it difficult to summon defence witnesses whilst confined in gaol. The judge himself led the questioning of witnesses. Defence lawyers were not permitted until c.1730, but by 1800 they were frequently conducting more searching interrogations of prosecution witnesses. It was not until 1836 that statute permitted them to sum up the defence before the jury.

Most juries in earlier centuries probably spent little time on their deliberations, taking their lead from the judge. Judges could dispute their findings, require them to change their verdict or order a re-trial. A jury that refused to find as a judge directed might be bullied, fined and even imprisoned. Judicial intimidation was not ruled illegal until Bushell’s 1670 case. William Bushell had been imprisoned when the jury he was a member of refused to find two Quakers guilty of holding an illegal ‘conventicle’. He sued out a writ of habeas corpus to the Court of King’s Bench, who ruled that, if a jury had to deliver a verdict as the judge dictated, there was no point in having a jury.23 Despite the difficulties faced by the defence, many not guilty verdicts were pronounced. In the Home Circuit, they constituted 40 per cent of cases between 1558 and 1625.24 Juries could also return a ‘partial’ verdict, reducing the gravity of the offence, and the punishment that could be inflicted.

Sentences on the guilty were passed at the close of the Assizes. Even those found not guilty could be punished by whipping or imprisonment, if the judge thought their behaviour warranted it. Otherwise, they were discharged, unless they failed to pay their fees. Before convicts were sentenced, they could make pleas in mitigation. Many claimed ‘benefit of clergy’. This was a privilege originally granted to the church, allowing it to punish criminous clergy.25 The church could not impose the death penalty, so felons sought to prove that they were clergy. In the medieval period, only clergy could read, so literacy became proof of entitlement to the benefit. Elton argues that benefit of clergy became ‘an absurd moderator on the absurd savagery of the eighteenth century law’.26

To claim benefit, convicts were asked to read the ‘neck’ verse from the Bible (Psalm 51: ‘O God, have mercy upon me, according to thine heartfelt mercifulness’). The illiterate could learn this by heart, so judges wanting to impose a severe punishment sometimes chose a different verse. From 1487, those not actually in orders could claim clergy only once. By 1706, many felonies had been made non-clergiable: murder, rape, poisoning, petty treason, sacrilege, witchcraft, burglary, theft from churches, pickpocketing and others. From that year, the benefit was automatically granted for all other offences; the reading test was abolished, although other offences were subsequently made non-clergiable, for example sheep stealing in 1741 and theft from the mails in 1765. Meanwhile, the obligation to turn clergied offenders over to the ecclesiastical courts had been ended in 1576. Felons were branded on the left thumb, or on the face between 1699 and 1706, and might be imprisoned for a year or two. Indictments were marked legit or clericus. Returns of those granted clergy were made to King’s Bench between 1518 and 1660; a few of these are in The National Archives, series KB 9; many were abstracted on the controlment rolls 1558–1625 (KB 29/192-273). The plea of clergy was abolished in the 1820s.

The Artful Dodger by George Cruickshank, from Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist.

Women could not make the plea until 1624, and not equally with men until 1691. They could not be clergy. They could, however, claim ‘benefit of belly’, that is, plead pregnancy. Execution would be stayed until after the baby was delivered. Claimants were examined by twelve matrons to determine their genuineness. But delay was frequent, giving women an opportunity to become pregnant before examination! Women reprieved on this plea were frequently gaoled, although a few were executed after giving birth.

Capital punishment was only inflicted on a few. Juries were reluctant to convict if hanging was likely to be the sentence. Whilst judges could be harsh, most sought to avoid pronouncing death sentences, or recommended conditional pardons. In the eighteenth century, perhaps half of those condemned to death were pardoned and imprisoned, or transported to the colonies.27 The purpose of the death sentence was to terrify, rather than to kill. It was valued for its supposed effect on those tempted to commit similar offences. Only a few hangings were needed to achieve that purpose.

Once Assizes were over, the Clerk of Assize endorsed the gaol calendar with the final disposition of the prisoners, and annotated indictments to indicate outcomes, in the same way that they were annotated at Quarter Sessions.28 If a felon was unable to claim clergy, the sentence was the ominous sus[pendatur] (to be hanged), or perhaps judic[ium] (judgement). Juries returning a not guilty verdict following a coroner’s inquest had to provide alternative explanations for the deaths, or accuse someone else. Fictitious names were frequently entered on indictments following coroners’ inquests.

By the late seventeenth century judges were submitting a ‘circuit pardon’ or ‘circuit letter’ at the end of each session, listing those recommended for pardon. From 1728, they prepared separate lists of those they wanted transported or pardoned absolutely. Recommendations are in many National Archives ASSI and SP series. Criminal entry books in SP 44 contain many entries relating to eighteenth-century pardons. Crown entry books (or agenda books) for the South Eastern Circuit (ASSI 31), commencing in 1748, constitute the best source for reprieves and pardons for the area covered. Judges’ reports on criminals (HO 47) between 1784 and 1830 contain detailed personal information.29 This series also include witness statements, character references, memorials and petitions from friends and relatives of the accused (or from parishioners who would have to support his family on the poor rates). Judge’s recommendations for mercy, 1816 to 1840, with lists of convicts, letters from prison governors, etc., are in series HO 6. Pardons themselves were entered on the Patent rolls, series C 66.30

Reprieve did not necessarily mean freedom; lesser punishments could be substituted. Convicts could be reprieved to serve in the armed forces. Branding, whipping and penal servitude with hard labour were common alternatives in the eighteenth century, although these began to be viewed with disfavour by the end of the century. Use of the pillory was abolished in 1837. For more serious offences, transportation and, subsequently, long-term imprisonment became increasingly common.

The prison hulk Discovery at Deptford.

Transportation as a punishment was introduced in 1598, although little used before 1617. It was not until the Transportation Act of 1718 provided central funding for transportation from the metropolis that it became a major alternative to capital punishment. Contractors were initially paid £3 for each convict transported, and were able to sell the services of convicts to the highest bidder. Convicts transported are listed in Peter Coldham’s The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage 1614-1775 (Genealogical Publishing, 1998). Coldham’s sources are described in his Bonded Passengers to America (Genealogical Publishing, 1983). Convict transportation registers for Dorset, 1724–91, have been digitised at http://search.ancestry.co.uk/search/db.aspx?dbid=2214.

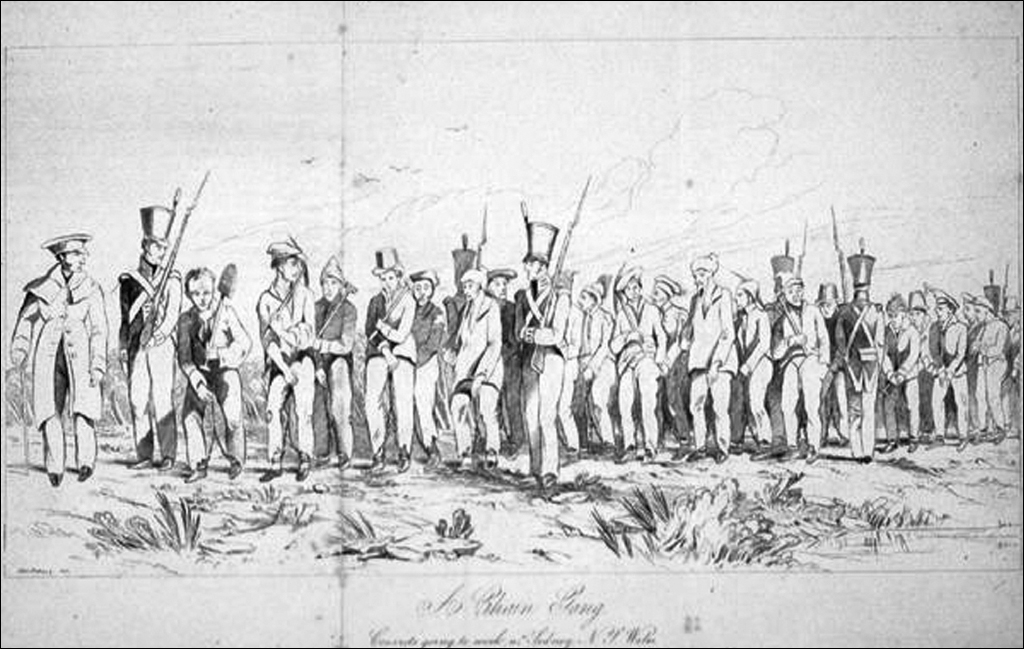

American independence halted transportation. Many convicts were instead incarcerated in the notorious hulks moored in the Thames Estuary, and expected to work in chain gangs along the river. Acts of 1776 and 1779 enabled judges to impose sentences of up to ten years in either hulks or Houses of Correction. These powers were used by the Assize judges much more than by Quarter Sessions, who had to pay the higher costs. Hulks provided an unsatisfactory means of punishment, expensive to run, and badly over-crowded. Mortality on board was high. Cook’s discovery of Botany Bay provided a much-needed alternative: it enabled many convicts to be sent to Australia, which became a penal destination for three-quarters of a century.

A chain gain: convicts going to work in New South Wales.

Australian transportation registers, 1787–1870, are in The National Archives, series HO 11, and digitised at Convict Records of Australia www.convictrecords.com.au.31 Many other relevant records have been microfilmed for the Australian Joint Copying Project www.nla.gov.au/microform-australian-joint-copying-project; the microfilm are available in major Australian research libraries, and its handbooks enable you to locate the original documents in England. A variety of other records are identified in ‘Criminal Transportee’ www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/criminal-transportees, and ‘Criminal Transportees: further Research’ www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/criminal-transportees-further-research/. Various county databases of transportees are listed at ‘Convicts to Australia: a guide to researching your convict ancestors’ http://members.iinet.net.au/~perthdps/convicts/list.html

Even after transportation to Australia had commenced, hulks continued to be used. Prison hulk registers and letters, 1802–49, are in The National Archives, series HO 9, and have been digitised at http://search.ancestry.co.uk/search/db.aspx?dbid=1989. The nineteenth century witnessed the increasing use of long-term prison sentences; the purpose of sentencing gradually became to reform depraved minds through work, solitude and religious instruction, rather than to punish their bodies.

Richmond Bridge, Tasmania, built entirely by the labour of convict transportees.

CIVIL AND ADMINISTRATIVE MATTERS

Civil cases began before one of the Westminster courts, and were directed to Assizes by writs of nisi prius sent to the Sheriff. In early seventeenth-century Somerset there were perhaps seventy cases at each Assize. These cases required more care by the judges, as both sides were likely to be represented by counsel. Final judgement was reserved for the Westminster courts, to whom records of the proceedings – posteas – were sent.

Administrative matters, such as bridge and highway maintenance, rates, the erection of cottages and unlicensed alehouses, had to be dealt with by presentment and indictment. Many cases were referred back to Quarter Sessions or individual Justices. No less than ninety-nine of the 163 Somerset orders in the Western Circuit Assize order book for 1629–40 required considerable out of sessions labour for the local Justices.32 Grand Jury presentments could be particularly important; in Interregnum Cheshire, the Jury criticised Justices of the Peace for allowing inadequate men to be appointed as constables, failing to hold regular monthly meetings in each Hundred, and neglecting to suppress alehouses. And they suggested candidates who would be suitable for appointment as Justices.33

CONCLUSION

An extraordinary range of topics came before Assize judges. Serious crime, the efficiency of local government, the regulation of enclosure, the oversight of economic projects, the maintenance of roads and bridges, the levying of taxation and relief of the poor, were all subject to their jurisdiction.

A more informal function of the Assize judges was to serve as the ears of the Council in the counties. Although the Council had many sources of information, none was as regular and reliable as the Assize circuit judges. They sat in court with the leading gentry, dined with them and were confided in by them; they judged their disputes. More formally, the petitions and presentments, examinations and informations they received allowed judges to assess the state of political opinion in their counties. Political allegiance and religious conformity were of prime concern to the Crown, at least in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Judges were charged to report ill-affected, negligent, and feuding magistrates, who should be put out of the Commission – the ultimate sanction, which ensured that most Justices obeyed Crown directives. Sometimes, they urged action; for example, in 1629 the Norfolk Circuit judges reported that something needed to be done to revive the cloth trade in Bury St Edmunds, or it would fail altogether.34

THE RECORDS

Unfortunately, pre-nineteenth century Assize records have suffered badly. Assizes were seasonal and itinerant; they did not develop a tradition of record keeping. As early as 1325 they were ordered to submit their rolls to the Exchequer, but it is doubtful if this order, or the subsequent statute of 1335, was ever consistently obeyed,35 at least until the nineteenth century. Clerks of Assize saw no point in keeping records not needed for current business.

The majority of surviving Assize records are in The National Archives, and particularly amongst the ASSI series. Survival from earlier than c.1800 is poor, although some earlier records have been printed (see below). Records from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries are held in JUST 3 and other JUST series.

At the close of Assizes, the Clerk prepared three documents recording its decisions: order books, gaol books and postea books. Order books record a wide range of general decisions by the court. In 1736, presentments at the Western Assizes were recorded in a separate process book; orders relating to transportation also had a separate book.36 Gaol books record convicts, noting plea, verdict and sentence. There may be separate series of minute books for particular offences, such as failure to repair roads and bridges.

The Clerks also returned their posteas, recording judges’ findings in civil cases. These were the basis on which Westminster court made their judgements. Postea books were kept by the Clerks of Assize for their own records; these, together with minute books recording civil trials, can now be found amongst the ASSI series. Posteas returned to the Westminster courts are amongst records of the relevant courts. For example, King’s Bench posteas, recording the initial proceedings, and endorsed with a record of the nisi prius proceedings at Assizes, are in KB20 for 1664–1829. Common Pleas posteas for 1573 to 1714 are in CP 36, and for 1830–52 in CP 42.

All the documents that came before the court were rolled up, perhaps using the nomina ministrorum or the gaol calendar as a wrapper. Sometimes these are referred to as indictment files, although they may also include precepts, jury panels, coroners’ inquests, recognizances, presentments, writs and other documents. Indictments were in Latin until 1733, except during the Interregnum. They appear to be a uniquely rich source of information on crime. However, the same strictures apply to Assize indictments as apply to those made at Quarter Sessions. They had to follow a set formula to be valid, but most give occupations as ‘labourer’, and most stated ‘residences’ are in fact the places where crimes were committed. Indictments and their related recognizances are frequently inconsistent. Medieval and early modern Assize indictments cannot safely be used as the basis for detailed economic and sociological investigation.37 Nor can they be used to tell us much about actual crimes, as opposed to legal categories. Indictments for homicide, for example, usually accuse the defendant of murder, even though deaths were known to be accidental. When indictments began to be drawn up by prosecuting lawyers in the late eighteenth century, they perhaps became more accurate and elaborate.

Gaol calendars record the prisoners brought to court by gaolers. Sometimes they take the form of a book; gaol books for the Western Circuit, 1670–1824, are in ASSI 23. Early calendars name the accused, the offence, and the committing magistrate. From the mid-eighteenth century, they began to be printed, and the information given gradually increased; by the 1840s, Staffordshire calendars give prisoners’ ages, literacy and states of health, with various other administrative details. Occupations and residences were added later in the century.38

Depositions (pre-trial statements of witnesses) tend to survive only in cases of murder and riot. Some from the seventeenth-century Northern circuit have been published (see below). Other records in ASSI on the criminal side include pleadings, coroners’ inquisitions, jury lists, draft minutes of trials and administrative papers.

Assize and Quarter Sessions gaol records are not always distinct. For example, gaol calendars from the Devon Assizes were entered in Quarter Sessions order books between 1598 and 1640, and intermittently from 1646 to 1651.

Most county record offices hold some Assize records; for example, the earliest order book of Wiltshire Quarter Sessions includes many minutes of Assize proceedings. Related papers may also be found amongst the records of other central government courts and departments. Sheriffs’ vouchers and cravings (E 389/241-57), detail payments for hanging, whipping and otherwise punishing Assize convicts between 1758 to 1832. Related payments to Sheriffs are recorded in T 53 (for 1676 to 1839), T 90/146-170 (for 1733 to 1822), and in T 207 (for 1823 onwards).

For the nineteenth century (1791–1892), the criminal registers (HO 27) record all indictable offences, including those tried at both Assizes and Quarter Sessions. Verdicts and sentences are noted, together with the dates of execution of persons sentence to death; sometimes they include personal information on prisoners. These registers can be searched at http://search.ancestry.co.uk/search/db.aspx?dbid=1590.

From 1868, gaolers were required to send both Assize judges, and Quarter Sessions, annual calendars of the prisoners they held. These include the following information: number; name; age; trade; previous convictions; name and address of committing magistrates; date of warrant; when received into custody; offence as charged in the commitment (includes name of victim before 1969); when tried; before whom tried; verdict of the jury; sentence or order of the court. Copies were sent to the Home Office, and are now in HO 140. Various other nineteenth century calendars of prisoners can be found in The National Archives, series PCOM 2.

The activities of Assize courts were of great interest to the general public. In Surrey, proceedings were regularly published commercially between at least 1678 and 1774. Gaol calendars and similar publications can be found for a few other counties. For London, the Proceedings of the Old Bailey (the capital’s equivalent of both Assizes and Quarter Sessions) run from 1674 to 1913, and are available online at www.oldbaileyonline.org. Reports from all courts regularly appeared in newspapers; many can be found by searching the British Newspaper Archive www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

FURTHER READING

This chapter is heavily indebted to:

• Cockburn, J.S. A History of English Assizes, 1558-1714. (Cambridge University Press, 1972).

• Cockburn, J.S. Calendar of Assize Records: Home Circuit Indictments, Elizabeth I and James I. Introduction. (HMSO, 1985).

• Criminal Trials in the Assize Courts, 1559–1971 www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/criminal-trials-Assize-courts-1559-1971

• Criminal Trials in the Assize courts, 1559–1971: key to records www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/criminal-trials-english-Assize-courts-1559-1971-key-to-records

For civil trials, see:

• Civil trials in the English Assize Courts 1656–1971: key to records www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/civil-trials-english-Assize-courts-1656-1971-key-to-records

There are a number of editions of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Assize records:

• Cockburn, J.S., ed. Western Circuit Assize Orders, 1629-1648: a Calendar. (Camden 4th series 17. Royal Historical Society, 1976).

• Raine, James, ed. Depositions from the Castle of York, relating to offences committed in the Northern Counties in the seventeenth century. (Surtees Society 40, 1861).

Cockburn has also edited many volumes of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century indictments for Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent, Surrey, and Sussex; for example:

• Cockburn, J.S., ed. Calendar of Assize records: Essex indictments Elizabeth I. (HMSO, 1978).

Other published Assize records include:

Gloucestershire

• Wyatt, Irene, ed. Transportees from Gloucestershire to Australia, 1783-1842. (Gloucestershire Record series 1. Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 1988). Based partially on gaol calendars.

Kent

• Knafla, Louis A., ed. Kent at Law 1602: the County Jurisdiction: Assizes and Sessions of the Peace. (HMSO, 1994).

• Barnes, T.G., ed. Somerset Assize Orders, 1629-1640. (Somerset Record Society 65, 1959).

• Cockburn, J.S., ed. Somerset Assize Orders, 1640-1659. (Somerset Record Society 72, 1971).

Staffordshire

• Johnson, D.A. Staffordshire Assize Calendars, 1842-1843. (Collections for a History of Staffordshire 4th Series 15, 1992).