4. The Turning Point in the Society and the Economy

The Reforms in the 1860s

In 1855, reformist Alexander II was appointed the czar of Russia. The Finns' loyalty to the czar during the years of revolutions in Europe and in the Crimean war (1853-1856) was rewarded. In 1863, Alexander II launched a reform plan that started to dismantle the class-based society.

The Diet of Finland was regularly summoned. Finnish was declared an official administrative language along side Swedish and Russian. The elementary school system was started, and municipal administration was separated from that of the church. Finland's autonomy developed further with regular Diet meetings, which increased political activity and interest in social affairs. The framework for a civic society started to take shape.

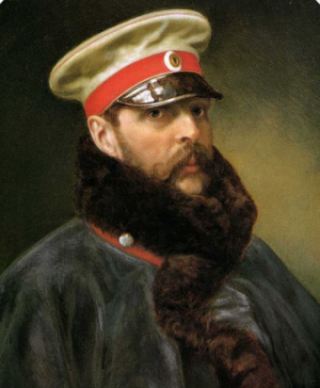

Czar Alexander II (1818 - 1881).

Fennomans, Svekomans, and Liberals

The first political groups were established in Finland in the 1860s. The key differences between the groups were related to language and culture. Continuous language conflicts drove the groups to form the first political parties that focused on language issues in 1870.

Fennomans consisted of peasants, the ministry, and students. Their mission was derived from Snellman's thoughts. Svekomans brought together educated Swedish-speaking people, nobility, and the middle class. They believed only Swedish-speaking people were capable of advancing civilization. Their goal was to maintain the situation as it was. Liberals believed reforms in the society were more important than the language.

The newspaper Uusi Suometar was the public voice for the Fennomans. Soon the Nuorsuomalaiset group separated themselves from the Fennomans. The Nuorsuomalaisets established the newspaper Päivälehti, which developed into Helsingin Sanomat in 1904. Helsingfors Dagblad was the Liberal's newspaper, as also briefly was Hufvudstadsbladet. Svekomans were supported by the newspaper Vikingen.

Heading towards the Civil Society

The initiative by Alexander II and active work by Snellman produced a new law that defined the elementary school system in Finland. The principle was to establish schools that were free to all children. The process for opening enough schools was slow, however.

The language conflict didn't help the development of the secondary school system. Financed by private funds, the Fennomans established the first Finnish-language secondary school in Jyväskylä.

Finnish school children at the end of 19th century.

In 1865, a law was passed that gave local communities self-governance rights. In the countryside, people without their own land were not eligible to participate in local communities' decision-making. The self-governance of towns was reformed as well. Every taxpayer could vote according to the amount of taxes paid. The impact of the reform was significant. Ordinary people could have a say in decision-making in the society.

As the European nationalism, liberalism, and labor movements developed, Finns also adopted those ideas. The ideas increased interest in politics. Since not all citizens had the right to vote, associations emerged as a channel to influence solutions to problems in the society. At the end of the 19th century, new associations were actively set up. The Association of Public Education, KVS (Kansanvalistusseura), taught literature, music, theater, and reading. The Association of Finland's Women (Suomen Naisyhdistys) improved women's rights in the society, as well as their economic and political status. The Temperance Movement (Raittiusliike) grew into the largest public movement in Finland, andmanaged to pass the Communal Prohibition Act.

A story with a lead character called Turmiolan Tommi depicted damages caused by alcohol. Sobriety education in Finland in the 19th century.

The labor class established associations that focused on education. In the 1890s, the movement adopted principles from socialism, driving business owners away from the movement. In 1899, the Finnish Labor Party (since 1903 the Social Democratic Party of Finland) was established.

Economy

Alexander II wanted to modernize Russia and push Finland into the ongoing industrial revolution. Mercantilism was replaced by economic liberalism, diversifying Finnish business and trade. The freedom to conduct business was approved in 1879. Craft guilds were disbanded, restrictions on steam sawmills were removed, and stores could be opened in the countryside as well.

Finland was allowed to have its own currency, the Mark (markka), stabilizing the monetary situation. The Finnish Mark was tied to the gold standard, stabilizing its value and preventing inflation. The number of commercial banks and corporations, and the amount of foreign investment increased in Finland at the end of 19th century. Banks contributed to the availability of capital and the ability to start new businesses. Citizens were free to move to places where work was available, boosting business and the economy.

The industrialization of Europe increased demand for timber, making it the most important export product from Finland in the mid-19th century. Finland's wood-processing and paper industry benefited from low-cost labor and a vast supply of raw material. The metal industry's development was boosted by industrialization and automation. In the early 19th century, the most significant industrial town was Tampere, where Finlayson established a textile factory.

James Finlayson (1771-1852), the Scottish industrial entrepreneur, established a factory in Tampere.

Both industry and trade required railway transportation. The first track was built from Helsinki to Hämeenlinna in 1862. Next, tracks were laid to St. Petersburg and to Tampere. Trade routes with St. Petersburg and connections to the Baltic Sea were further improved after the Saimaa Canal was opened up. The telegram, telephone, and electricity started to change the daily life of Finns. The demand for consumer goods increased.

The thriving economy improved the standard of living both in towns and in the countryside. In the 1860s, a number of famine years forced Finns to diversify their farm production. Dairy production increased, and automation of work started. The growth of the forest industry increased land owners' income, because they could sell timber to the factories.

The Changing Society

Driven by the economy, reforms, and active civil movements, the structure of the Finnish society had reached a turning point. Industrialization encouraged citizens to migrate to towns, drove the development of cities, and caused emigration. The majority of emigrants moved to the United States, Canada, and Russia.

Roles of the lower and upper classes began to shift as the assets owned by a family were regarded to be more significant than the family's origins. The differences between citizens reached a peak at the end of the 19th century. The number of people living in the countryside without their own piece of land was increasing. Particularly, 50,000 tenant farmers who leased their farmland were in a difficult judicial and economic position. With minimal political power, the working class felt mistreated as well.

The First Period of Oppression (1899 – 1905)

At the end of the 19th century, Russia tightened its grip on its borders, including Finland. Fanatic Slavophiles demanded the conversion of the multinational country into a single Russian state, while reformists demanded modernization of the society.

Russians were provoked by Finland's customs border, the inability to appoint Russians as civil servants, and because only a few Finns spoke Russian. Russians were also concerned about Europe's superpowers, which were forming alliances. Germany, which was united in 1871, was regarded as a threat as well. The envisioned risk was Germany's potential support to the countries along Russia’s borders. These border countries might attempt independence, threatening the safety of the capital, St. Petersburg.

Russia began to "Russify" Finland. According to the program, the Finnish army would have to integrate with the Russian army, Russians would be appointed to administrative positions, and the laws of the two countries would have to be unified. The Diet refused to approve the law for compulsory military service. This situation culminated in the February Manifesto of 1899, issued by Nicholas II, which started the first period of oppression, from 1899 to 1905.

Czar Nicholas II (1868 - 1918) with his family.

The new legislation allowed Russia to set general laws, while The Diet of Finland was limited to issuing statements concerning the planned laws. Finland's Post Office was closed down in 1890. Russia was declared the official language for administration. The Finnish army was disbanded. In 1904, Finland’s people were relieved from compulsory military service because of strikes during conscription. Finland had to pay additional military taxes.

The unification process led to censorship, newspaper closures, the firing of civil servants, and deportations. Finally, Finns awoke to defend their autonomy. Two petitions, the so-called Great Address and Pro Finlandia were delivered to Nicholas. The Czar ignored them.

Many Finnish artists opposed Russian activities as well. The national Romantic Art movement supported the Finnish people’s political demands and improved the Finns' self-esteem. Some of the most significant artists from the Golden Age of Finnish Art were Albert Edelfelt, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Eliel Saarinen and Jean Sibelius.

Composer Jean Sibelius (1865 - 1957) opposed the Russian oppression.

Attitudes toward Russification

Russia's unification policy split the political movements in Finland into those who were compliant (traditionalists), supporters of the constitution (Swedish party, labor movement), and activists (the educated Swedish-speaking class). The compliant group wanted to retain good relationships with the emperor. Oppression had to be tolerated in order to retain the Finnish culture. The constitutional group regarded this "Russification" as oppression against the constitution, and refused to obey the new rules. They conducted passive resistance. Activists were ready for violence. The labor movement objected to “Russification” as well, but regarded reforms in the society to be even more important objectives.

In 1904, after Finnish activist Eugen Schauman murdered Russian governor-general Nikolai Bobrikov and committed suicide, the situation was critical. The next year, a general strike in Russia spread to Finland as well. Finally, Nicholas II approved the demands for reforms in order to end the disturbances. The so-called November Manifesto ended the “Russification” activities.

Parliament Reform in 1906

Thanks to the November Manifesto, Finland's Parliament could be reformed into the most modern parliament in Europe. Democracy took over when the old Diet was replaced by a 200-seat unicameral Parliament. Now, ten times as many citizens had the right to vote. Every 24-year-old citizen had the right to vote, including women. However, the new election system did not apply to the municipal elections.

Some of the women elected as Members of Parliament. Women got the right to vote in Finland in 1906.

The new system forced political parties to organize themselves and to conduct active campaigns for the elections. In 1907, the first Parliamentary elections were organized in Finland. The right wing won the majority of the 200 seats. Social Democrats won 80 seats. The emperor still had the right to dissolve the Parliament.

The Second Period of Oppression (1908 – 1917)

In 1908, the oppressive movement to form a nationally united Russia resurged. Laws concerning Finland were submitted to the council of ministers before passing them on to the emperor. The power of Russian civil servants over Finland's administration increased. The Parliament didn't approve the changes.

The pace of unification activities was speeding up. In 1910, Russia ordered all matters, excluding Finland's internal affairs, to be sent to the Russian State Duma. In 1912, the Equal Rights Law guaranteed civil rights for Russians, who could also work as civil servants, and who could conduct business in Finland.

Finland's "Russification" was set to be completed in 1914. However, the plan wasn't put into action because the First World War broke out. Finland was declared to be in a state of war.

Russia's poor showing in the war, and its severe internal problems, created a crisis. In March 1917, revolution broke out. The emperor was dethroned. The "Russification" activities were cancelled, ending Finland's Second Period of Oppression.

Jaeger Movement

The plans for Finland's total "Russification" had prompted students to establish the Jaeger movement. The objective for Jaegers was to form an army of its own and to separate from Russia. About 2,000 Finns, from many classes of society, traveled to Germany for military training. Germany supported the independence plans of the countries on Russia's borders in order to weaken Russia. In Germany, Finns formed the Royal Prussian Jaeger Battalion No. 27. The Battalion was to have a significant role later in Finland's history.

Finnish Jaegers were trained in Germany.