DOCUMENT 4: The Human Rights Commission and Blacks in America

While the HRC worked on drafting the Declaration, some of those leading the struggle for civil rights in America believed that bringing their case before the United Nations would draw helpful international attention. They felt that a change in terminology—from “civil rights” to “human rights”—would align their struggle with that of other oppressed groups and colonized nations around the world.

This was the strategy employed by W. E. B. Du Bois, who served as the director of research at the NAACP. He gathered a team of lawyers and scholars, and the group drew up a brief explaining the status of blacks in America. The comprehensive document—“An Appeal to the World: A Statement of Denial of Human Rights to Minorities in the Case of Citizens of Negro Descent in the United States of America and an Appeal to the United Nations for Redress”—was submitted to the human rights division of the United Nations in 1947.

Eleanor refused to participate in the meeting when “An Appeal to the World” was presented. She claimed that, among other things, the appeal would be used by the Soviets to condemn America, which would force her, in her position as a representative of the United States, to defend America’s racial policies. Eleanor, by this time a well-known critic of racial discrimination in the United States, felt that if she were to be put in this awkward position, she would have to resign from the United Nations. As a compromise, Eleanor referred the issue of racial discrimination in the United Nations to a Human Rights Commission subcommittee. While Du Bois continued to press the issue, the NAACP changed its tactic. The organization decided that Walter White, not Du Bois, should be its representative to the delegation. In his introduction to the document below, Du Bois questioned how a government determined to lead the free world could turn a blind eye to daily acts of racist terror. He argued that segregation—a practice taken for granted by most white Americans—led to a gross violation of the human rights of African Americans.

There were in the United States of America, 1940, 12,865,518 native-born citizens, something less than a tenth of the nation, who form largely a segregated caste, with restricted legal rights, and many illegal disabilities. They are descendants of the Africans brought to America during the sixteenth, seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, and reduced to slave labor. This group has not complete biological unity, but varies in color from white to black, and comprises a great variety of physical characteristics, since many are the offspring of white European-Americans as well as of Africans and American Indians. There are a large number of white Americans who also descend from Negroes but who are not counted in the colored group, nor subjected to caste restrictions because the preponderance of white blood conceals their descent.

The so-called American Negro group . . . has . . . a strong, hereditary cultural unity, born of slavery, of common suffering, prolonged proscription and curtailment of political and civil rights; and especially because of economic and social disabilities. Largely from this fact, have arisen their cultural gifts to America—their rhythm, music and folk-song; their religious faith and customs; their contribution to American art and literature; their defense of their country in every war, on land, sea and in the air; and especially the hard, continuous toil upon which the prosperity and wealth of this continent has largely been built. . . .

If however, the effect of the color caste system on the North American Negro has been both good and bad, its effect on white America has been disastrous. It has repeatedly led the greatest modern attempt at democratic government to deny its political ideals, to falsify its philanthropic assertions and to make its religion to a great extent hypocritical. A nation which boldly declared “That all men are created equal,” proceeded to build its economy on chattel slavery; masters who declared race mixture impossible, sold their own children into slavery and left a mulatto progeny, which neither law nor science can today disentangle; churches which excused slavery as calling the heathen to God, refused to recognize the freedom of converts, or admit them to equal communion . . .

But today the paradox again looms after the Second World War. We have recrudescence of race hate and caste restrictions in the United States, and of these dangerous tendencies not simply for the United States itself, but for all nations. When will nations learn that their enemies are quite as often within their own country as without? It is not Russia that threatens the United States so much as Mississippi; not Stalin and Molotov, but Bilbo99 and Rankin100; internal injustice done to one’s brothers is far more dangerous than the aggression of strangers from abroad . . .

It may be quite properly asked at this point, to whom a petition and statement such as this should be addressed? Many persons say that this represents a domestic question which is purely a matter of internal concern; and that therefore it should be addressed to the people and government of the United States and the various states.

It must not be thought that this procedure has not already been taken. From the very beginning of this nation, in the late eighteenth century, and even before, in the colonies, decade by decade, and indeed year by year, the Negroes of the United States have appealed for redress of grievances, and have given facts and figures to support their contention.

It must also be admitted that this continuous hammering upon the gates of opportunity in the United States has had [an] effect, and that because of this, and with the help of his white fellow citizens, the American Negro has emerged from slavery and attained emancipation from chattel slavery, considerable economic independence, social security, and advance in culture.

But manifestly this is not enough; no large group of a nation can lag behind the average culture of that nation, as the American Negro still does, without suffering not only itself but becoming a menace to the nation.

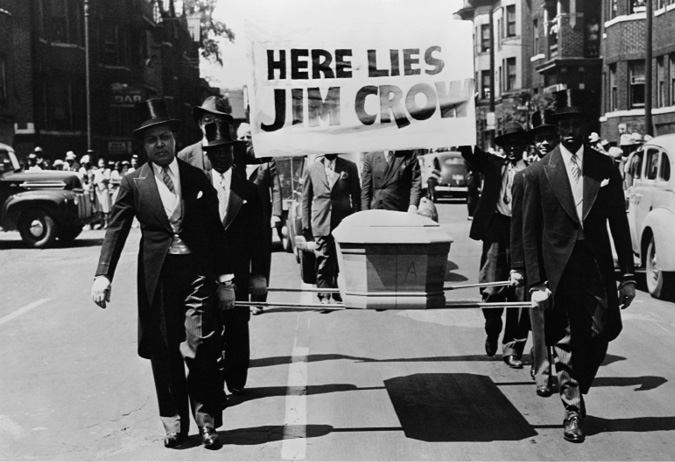

Demonstration against Jim Crow segregation laws, 1944. In an essay entitled “Abolish Jim Crow,” Eleanor spoke of the need “to align the ethical mission of the war abroad and the struggle for justice at home.”

© Bettmann/Corbis

In addition to this, in its international relations, the United States owes something to the world; to the United Nations of which it is part, and to the ideals which it professes to advocate. Especially is this true since the United Nations has made its headquarters in New York. The United States is honor bound not only to protect its own people and its own interests, but to guard and respect the various peoples of the world who are its guests and allies. Because of caste custom and legislation along the color line, the United States is today in danger of encroaching upon the rights and privileges of its fellow nations. Most people of the world are more or less colored in skin; their presence at the meetings of the United Nations as participants, and as visitors, renders them always liable to insult and to discrimination; because they may be mistaken for Americans of Negro descent . . .

This question, then, which is without doubt primarily an internal and national question, becomes inevitably an international question, and will in the future become more and more international, as the nations draw together. In this great attempt to find common ground and to maintain peace, it is therefore fitting and proper that thirteen million American citizens of Negro descent should appeal to the United Nations, and ask that organization in the proper way to take cognizance of a situation which deprives this group of their rights as men and citizens, and by so doing makes the functioning of the United Nations more difficult, if not in many cases impossible.101

Connections

- What main concerns does Du Bois raise? What argument does he make to support his assertion that civil rights issues are, indeed, human rights issues?

- Why would Du Bois want to submit this document to the human rights division of the United Nations? What did he hope to accomplish?

- As a board member of the NAACP and a member of the United States delegation to the United Nations, this petition created a dilemma for Eleanor. What dilemma did this raise for her? How do you evaluate her response? What do you think is the right thing to do with a petition like this in that situation?

- Why do you think that Eleanor said that she would resign from the United Nations if she were forced to defend America’s racial policies?