The New Revolution in Biology

GARY W. BARRETT AND W. JOHN KRESS

As early as the 1970s numerous reports and publications stressed the crucial leadership role in social and economic development that biology would be required to assume as scientists began to plan for the end of the twentieth century and beyond. For example, Philip Handler (1970), then president of the National Academy of Sciences, noted that “the forces shaping the short-term future of man, perhaps to the turn of the Century, are apparent and the events are in train. The shape of the world in the year 2000 and man’s place therein will be determined by the manner in which organized humanity confronts several major issues. If sufficiently successful, and mankind escapes the dark abysses of its own making, then truly the future belongs to man, the only product of biological evolution capable of controlling its own further destiny.”

Further, a National Research Council report in 1970 from the Committee on Research in the Life Sciences (NRC 1970), chaired by Harvey Brooks, Harvard University, listed ten frontiers of biology, ranging from the origin and language of life to the diversity of life. However, this report also stressed the deterioration in quality of the planet’s air, water, and soil fertility. Critics noted that this deterioration was proceeding most rapidly in technologically developed nations and that this growing threat to the quality of life and, indeed, to the habitability of the planet constitutes a profound human issue. This report noted that “although the life sciences, even now, are capable of contributing significantly to this critical enterprise, the science of ecology, while crucial, is still developing; its capabilities are limited as is the number of ecologists. It must be clear that ecological understanding rests upon the totality of all other biological understanding.… Thus, continuing advancement of understanding along all biological fronts is essential to the development of ecological understanding.” Here we should note that the 1970s were frequently referred to as the “Decade of the Environment.” Needless to say, the marriage of biological progress with ecological understanding continued through the remainder of the twentieth century.

In the proceedings following an international conference entitled “Biology and the Future of Man,” held in Paris in 1974 (Galperine 1976), Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, president of France, stated, “There is no doubt that mathematics, physics, and other sciences rather ill-advisedly referred to as ‘exact’—very likely by contrast with economics—will continue to afford surprising discoveries. Yet, I cannot help feeling that the real scientific revolution of the future must come from biology.”

Thus, since at least the 1970s an optimism has prevailed that biology would play a lead role in improving the quality of humankind, including the environment in which we reside. The chapters in the present volume illustrate that we not only have avoided most of the abysses Handler referred to but are rapidly developing the technologies, database, and transdisciplinary approaches necessary to solve the problems that loom in our future. As societies begin to address challenges and opportunities associated with a world at carrying capacity (Barrett and Odum 2000), we visualize a future with a “glass more than half full” thanks to accomplishments during the past century. The authors of the following chapters provide a glimpse of the twenty-first century and how the life and environmental sciences are likely to seed a new revolution in integrative biology as a result of this era of accomplishment.

Without question the twentieth century was a seminal epoch for the study of biology as measured by its conceptual advances, its research support for areas such as medicine and agriculture, and its growing importance to our future (Bock 1998). At the close of the twentieth century numerous scholars and reporters attempted to highlight events and milestones of the past hundred years in fields such as military battles, climatic phenomena, athletics, and advanced technologies. The encyclopedic accomplishments and discoveries in biology, however, were so diverse and profound that few attempts have been made to provide a comprehensive overview. Instead summaries or reflections were presented in select areas, such as the top one hundred or so books that shaped the century of science (Morrison and Morrison 1999). Likewise, several scholars have attempted a vision regarding how science will revolutionize the twenty-first century (Murphy and O’Neill 1995; Kaku 1997). However, for the most part large professional societies did not simultaneously try to reflect on major accomplishments of the past century and to visualize the challenges and opportunities that biologists must address during the next. Such a synthesis is one of the major goals of this book.

At the beginning of this new century we are faced with a biological paradox of the last one hundred years—namely that the unparalleled advances in areas such as molecular, cellular, and organismal biology were coupled with greatly increased problems related to the world’s human population growth, food production, energy resource management, biotic diversity, and landscape fragmentation. Ernst Mayr in his book This Is Biology (1997), an excellent overview of the field during the past century, addressed this paradox. He not only stressed the integrative role of evolutionary theory during the last hundred years but pointed out that biology at the organismal level and below will need to be coupled with holistic approaches as societies address problems related to overpopulation, environmental degradation, and resource management. He wrote, “Overpopulation, the destruction of the environment, and the malaise of the inner cities cannot be solved by technological advances, nor by literature and history, but ultimately only by measures that are based on an understanding of the biological roots of these problems.” It is no wonder that Ernst Mayr, a leading evolutionary biologist of this century, provides the foreword to the present volume.

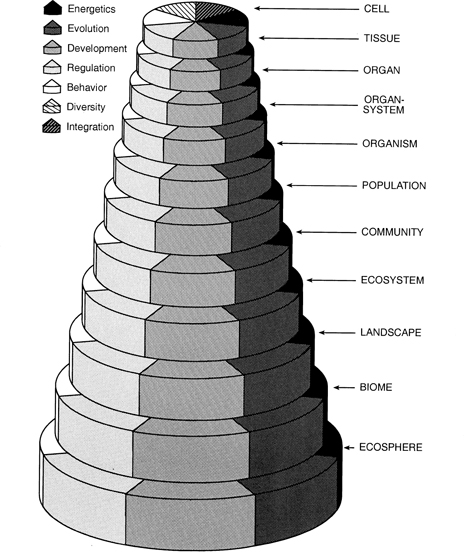

The core chapters of this volume are devoted to contributions from internationally renowned scientists who were invited to address the processes (i.e., energetics, evolution, development, regulation, behavior, diversity, and conservation) that transcend all levels of biological organization (see Figure 1.1; Barrett et al. 1997). The authors were selected to maintain (a) a balance among the levels of biological organization; (b) an emphasis on integrative processes among levels of organization; and (c) an organization that highlighted transdisciplinary accomplishments in all fields of the life sciences rather than narrow intradisciplinary work. These chapters thus represent a breadth of insight and experience across a wide range of the biological sciences.

Here we outline ten integrative topics that provide food-for-thought concepts for the volume as a whole. These areas are not intended to be in any ranked order nor are they all-encompassing. We hope that they will provide readers, especially graduate students and others wanting to better understand opportunities in biology, with challenges that will contribute to making the twenty-first century one that will be recognized for the integration of humankind with our biological and technological systems.

Figure 1.1. Model of transverse processes across levels of biological organization (from Barrett et al. 1997).

• Synergism. Throughout each chapter readers are encouraged to understand how synergistic and mutualistic processes operate within cells, organisms, and populations at one level as well as between ecological and social systems at another. Synergy is defined here as combined action or operation. Lynn Margulis (Chapter 2) attacks the neo-Darwinian paradigm and presents new ideas on the interactions of microbes in the origins of species, especially with regard to the source of evolutionary novelty. She describes the evolution of complex unions in the origin of the eukaryotes and outlines the microbial contribution to the evolution of life.

• Optimization. Several chapters portray how evolutionary processes, including morphologies, behaviors, and energy transformations, are optimized for functional efficiency at each level of organization. This optimization process ranges from transfer of genetic information at the molecular level to energy efficiencies at the ecosystem level. More specifically, Marvalee Wake (Chapter 3) addresses the optimization and integration of morphology (as the structural basis for an organism’s interaction with the environment) and development (as the process by which morphology is achieved). She suggests that the monogamous marriage of developmental studies with evolutionary theory is clearly the foundation of a new, if not rejuvenated, discipline in the biological sciences. She also speculates on the future polygamous relationship of developmental biology with evolutionary, ecological, genetic, and molecular sciences. In Chapter 5 Gordon Orians asks the question “How does animal behavior intersect with modern concepts of evolutionary and ecological theory?” He recognizes that it is hard to admit that the concept of free will may be compromised by an evolutionary explanation of human behavior. He also points out that parsimonious interpretations of phylogenetic data are powerful new tools in the study of the evolution of behavior.

• Optimism. Without exception contributors note that the twenty-first century will result in less emphasis on disciplinary training and greater focus on interdisciplinary and team approaches to research and problem solving. Gene Likens (Chapter 4) points out that interactions between natural ecosystems and society must be a major concentration of biologists in the near future. He stresses the practical aspects of scientific team building, the evaluation of ecological complexity, the accumulation of long-term environmental data, and the use of new technological tools as priorities and opportunities for solving ecological issues in the future.

• Conservation. Conservation—the careful preservation or protection of an entity—is a common theme throughout this book. Whether one is referring to the conservation of energy, matter, genetic material, endangered species, or wilderness areas, this priority will increasingly dominate resource management, political decision making, and national and international research cooperation well into the twenty-first century. Society increasingly views Biosphere I—the Earth—as a total system intricately interconnected and possessing regulatory mechanisms and mutualistic relationships. These processes—the core of these chapters—and relationships must be preserved to ensure a quality of life for all. A very clear picture of our biologically stressed planet is provided by Sir Ghillean Prance (Chapter 6) and Thomas Lovejoy (Chapter 7), who note that there is still much to learn about the diversity of life. Over twenty thousand new species of vascular plants alone, one of the best known groups of organisms, were described over a recent nine-year period, indicating that systematists have much work remaining in the inventory of the world’s taxa. Prance also bluntly challenges biologists to accept the responsibility of addressing the political nature of what they do as natural historians.

• Sustainability. Robert Goodland (1995) defines sustainability as “preserving nature’s capital.” By understanding the processes (e.g., evolution, regulation, and integration) that transcend all levels of organization, societies will be informed in a way that programs such as preserving biotic diversity will be based on an educational incentive rather than a regulatory mandate. Such a research, educational, and service agenda should result in both sustainable ecological systems and a sustainable society. Daniel Janzen develops this central theme in his discussion of the “gardenification of nature” (Chapter 8). After years of effort in Costa Rica, he reluctantly accepts that we will never have a smooth transition between society and the preservation of biodiversity, but he insists that we must “know it (i.e., biodiversity) and use it in order to save it.”

• Consilience. Edward Wilson (Chapter 9) defines consilience as cause-and-effect explanation across disciplines. Exploring consilience requires experiments and research designs resulting in strong inference (Platt 1964). These designs and approaches, whether they are established at or within molecular or human-dominated systems, should continue to revolutionize the biological sciences well into the twenty-first century. Such investigations will require a level of cooperation and unity of knowledge based not on technologies (which are largely available at present) but on human values and societal enlightenment. Wilson suggests that the great future frontiers of biology will include evolutionary genomics, biodiversity research, large-scale community ecology, and linkage of biology to the humanities and the social sciences. He views human nature as the product of the epigenetic rules of our evolutionary heritage, which can only be understood within the perspective of our biological nature.

• Holism. During the past two decades several scholars (e.g., Brown 1981) called attention to two “schools of research philosophy,” namely the ecosystem ecology school, led by Eugene P. Odum, which concentrated on the flow of energy and matter through systems and emphasized mutualistic interactions between organisms and the physical environment, and the evolutionary biology school, led by the late Robert MacArthur, which concentrated on evolutionary interactions between and among species with emphasis on community organization, competition models, and species diversity. It is apparent, as we enter the twenty-first century, that systems ecologists are including evolutionary factors (e.g., secondary chemistry, microbial interactions, and foraging strategies) in systems models, and that evolutionary biologists are increasingly addressing macroecological factors (e.g., global climate change, landscape patch diversity, and nutrient cycles) as they investigate questions at the microevolutionary scale. In other words, as we enter this new revolution in biological thought, there exists a coupling of reductionist science and holistic science, including the social sciences. Barrett and Odum (1998) refer to this holistic and integrative approach to addressing societal problems as “integrative science”—a new type of science developed along the lines of C. P. Snow’s “third culture” (Snow 1963).

In summary, we trust that A New Century of Biology will give cause to reflect and to appreciate the evolution of the biological sciences. We also hope it will give cause for all to participate in this new biology during the twenty-first century. It provides a niche for each citizen of every society in the years ahead.

Barrett, G. W., and E. P. Odum. 1998. From the president: Integrative science. BioScience 48:980.

———. 2000. The twenty-first century: The world at carrying capacity. BioScience 50:363–68.

Barrett, G. W., J. D. Peles, and E. P. Odum. 1997. Transcending processes and the levels-of-organization concept. BioScience 47:531–35.

Bock, W. J. 1998. The preeminent value of evolutionary insight in biological science. Amer. Sci. 86:186–87.

Brown, J. H. 1981. Two decades of homage to Santa Rosalia: Towards a general theory of diversity. Amer. Zool. 21:877–88.

Galperine, C., ed. 1976. Proceedings of the international conference Biology and the Future of Man. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Goodland, R. 1995. The concept of environmental sustainability. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 26:1–24.

Handler, P., ed. 1970. Biology and the future of man. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Kaku, M. 1997. Visions: How science will revolutionize the twenty-first century. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell.

Mayr, E. 1997. This is biology: The science of the living world. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, Belknap Press.

Morrison, P., and P. Morrison. 1999. One hundred or so books that shaped a century of science. Amer. Sci. 87:542–53.

Murphy, M. P., and L. A. J. O’Neill. 1995. What is life—The next fifty years: Speculations on the future of biology. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

National Research Council. 1970. The life sciences: Recent progress and application to human affairs. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences.

Platt, J. R. 1964. Strong inference. Science 146:347–53.

Snow, C. P. 1963. The two cultures: A second look. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press.