With that simple statement Mathew B. Brady explained why he had risked both his life and his fortune to give America a photographic record of the Civil War. Brady had already changed the way people viewed their world by becoming a pioneer in the field of photography. Soon he would change the nation’s attitudes toward war.

Born in 1823 in Warren County, New York, Brady became fascinated with paintings as a child and decided he wanted to be an artist. An ambitious young man, he was able, at the age of sixteen, to gain an apprenticeship with the well-known painter William Page.

Mathew Brady said that “from the first. I regarded myself as under obligation to my country to preserve the faces of its historic men and mothers.”

On a fateful day in 1839, Page introduced his apprentice to a fellow artist and friend, Samuel F. B. Morse. A professor of painting and design in New York, Morse was a man of many interests and had just completed his first invention. He called it the telegraph, and it would revolutionize the world of communications.

But Morse already had another new interest. He had recently returned from Paris where he had met with Louis Daguerre. The Frenchman had just astounded the prestigious French Academy by demonstrating his success in capturing permanent images through the lens of a camera, something that inventors and scientists had been trying to accomplish for hundreds of years. Daguerre had shown Morse how to produce such pictures, which he called daguerreotypes, and now Morse was starting a class in the astounding new process.

To Brady, daguerreotypes were miraculous. There before him was a picture of a person—not an interpretation drawn by an artist but an exact likeness of the individual. Young as he was, Brady realized that this new invention, which would come to be called photography, would change the world. He enrolled in Morse’s class.

Brady quickly mastered techniques of the new daguerrotype process. He was so adept that he soon learned all that Morse could teach him. On his own, he began experimenting with ways to produce the most interesting pictures possible.

It was not easy. In those days people had to sit before the camera for as long as thirty minutes in order for an image to take. And they had to remain perfectly still. Head clamps were often used to keep subjects from moving. Because artificial lighting had not been perfected, the earliest daguerreotypes were taken outdoors in full sunlight. Many of those who sat for photographs came away with a sunburn and only a single image for their trouble, since daguerrotypes could not be reproduced.

Yet almost everyone felt that the painful experience was worth it. For the first time, people have exact likenesses of themselves to share with their relatives and friends. And most could afford it. Unlike artists’ portraits, which were so costly that only the wealthy could have them made, daguerreotypes were relatively inexpensive.

Soon there were daguerreotype studios in almost every city in the United States. Most of them were run by unskilled photographers who wanted only to earn a living from their work. But Mathew B. Brady took a different approach.

Brady’s New York City photographic gallery was a beehive of activity in which more than thirty thousand portraits were produced every year.

Rather than opening his own studio immediately, he spent almost five years perfecting his skills and reading everything that had been published on the new art. He consulted with scientists, seeking ways to improve the chemical aspects of the daguerreotype process. He took scores of pictures, experimenting with different types of poses and props that would allow him to create images that were far more appealing than those being turned out by most of the other early photographers. One of his major innovations was the introduction of a huge skylight as part of his photographic setup, which made it possible to take pictures as effectively indoors as in full sunlight.

Finally, in 1844, at the age of twenty-four, Brady opened his own establishment. He rented rooms on the top floor of a building at the busy corner of Broadway and Tenth Street in New York City and announced he was ready for business. It was more than just a studio, for there was also a gallery where a large number of Brady’s daguerreotypes were displayed.

Brady understood from the beginning that if he was to outdistance his competitors he could not go it alone; rather, he would need to put together the best team of camera operators, chemists, retouchers, colorists, and other assistants he could assemble. He took very few of the pictures himself, leaving that to the camera operators. Instead, he coordinated the talents of all his assistants and concentrated on the more creative aspects of setting up the pictures, particularly that of determining the most interesting angles from which the photographs were to be shot.

Brady’s gallery caused a sensation. People flocked there to view the pictures on display and to have their likenesses recorded. Many famous political leaders and celebrities also came to have their pictures taken.

Buoyed by his success, Brady soon opened a second studio in Washington, D.C., where he would be even closer to the prominent political figures of his day. There he photographed every living president of the United States, from John Quincy Adams to William McKinley.

Unquestionably the most important person Brady photographed was Abraham Lincoln. He took his first picture of Lincoln during the 1860 presidential campaign, a time when the tall, gangly candidate was unknown to most Americans and was commonly portrayed as an ugly country bumpkin by cartoonists who supported his opponent. Brady photographed the future president just before he delivered an important speech at Cooper Union in New York. Aware of the importance of the picture, Brady used all his skills to produce an image that would present the candidate in the most appealing, dignified manner possible.

Thousands of copies of Brady’s Cooper Union portrait of Abraham Lincoln were sold throughout the nation and drawings made from the image were published in leading newspapers of the day.

The pictures taken by Brady’s corps of Civil War cameramen, including those of the various troops drilling between battles, marked the beginning of American military photography.

By this time, Brady had learned a brand-new photographic process, one that used a glass wet-plate negative. It was coated with a sticky substance, which meant that it had to be developed as soon as the picture was taken, before the substance dried. Although it had this drawback, it had a major advantage over the daguerreotype process: Many copies of a particular photograph could be reproduced from a wet-plate negative.

Delighted with the result of the portrait Brady had made, Lincoln had his campaign workers distribute the photograph throughout the country. When Lincoln won the election, he publicly declared that “Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me president.” Brady took many of the best-known photos of Lincoln, including the one used as the model for the Lincoln penny.

If Mathew B. Brady had never taken another picture after 1860, he still would have gone down in history as a photography giant, the man who gave Americans a new way of viewing their world. But in 1861 the Civil War erupted into the most tragic conflict in the history of the United States.

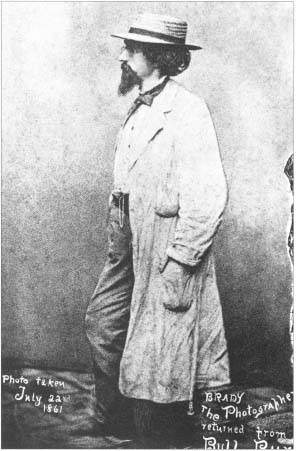

Brady made an important decision. He would travel to the Civil War camps and battlefields and give the nation a photographic record of the war. With President Lincoln’s permission, Brady organized a team of more than twenty photographers to help him. He supplied the team with a huge array of cameras, chemicals, and other equipment, and with horsedrawn wagons to carry the gear.

Although the cameras of their day could not record movement, Brady’s photographers were able to depict the devastating nature of the war by showing weapons that were far more destructive than any previously used in combat.

Brady and his photography corps captured thousands of images of soldiers as they relaxed in camp, drilled during periods between battles, and operated some of the largest weapons the world had ever known. Field hospitals, long lines of supply wagons, acres of piled-up munitions, military trains, hastily erected bridges, telegraph corpsmen, nurses and doctors—everything that had to do with the war was photographed. Mathew Brady and his team were the first photographers to record a major event in the nation’s history.

However, the most telling of all the images were those of the thousands from both armies who lay dead and dying on the battlefields. When the war had begun, the North and the South had each believed that it would be a brief conflict. Many had cheered on their departing troops as if they were embarking upon a great adventure. Brady and his photographers changed all that. Their haunting pictures disclosed the incredible price in human lives paid by both sides.

The Civil War photographs dramatically disclosed how young many of the combatants on both sides were. This fourteen-year-old Confederate private was killed in battle shortly after Brady took his picture.

Photos of dead Union and Confederate soldiers lying side by side did more to shock Americans into an awareness of the horrors of war than words could ever have accomplished.

The photos were sent straight from the battlefields to be displayed in Brady’s studios, where they made the horror of war inescapable. The nation was shocked. “Mr. Brady,” stated one newspaper, “has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war.” Thanks to Mathew B. Brady, Americans would never look at war in the same way again.

Brady and his photographers gave the nation an unforgettable portrait of the physical destruction brought about by war, as this picture of once-beautiful Richmond, Virginia, clearly shows.