said the photography historian Reginald McGhee after he had viewed thousands of pictures taken by renowned African-American photographer James Van Der Zee. “You will not see downtrodden rural or urban citizens,” McGhee promised. “Instead you will see a people of great pride and fascinating beauty.”

Born in 1886, Van Der Zee grew up in Lenox, Massachusetts, which at that time was a summer retreat for wealthy New Englanders. His parents, who had been servants of Ulysses S. Grant when he was president, were better off financially than most African Americans of their day, and Van Der Zee was raised in a house filled with music and art.

When he was fourteen, Van Der Zee read a magazine advertisement that would change his life. The company that placed the ad stated it would send a box camera to anyone who sold twenty packets of its perfumed powder. The camera Van Der Zee received proved to be worthless, but the book of instructions that accompanied it fascinated him. He soon bought a better camera and began taking pictures of his friends and family.

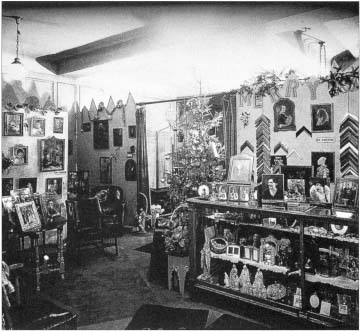

Van Der Zee’s photographic studio was one of the most elegant in the country.

At the age of twenty, Van Der Zee moved to a section of New York City called Harlem. There he founded a five-piece orchestra, but when that failed he earned his living as both a waiter and an elevator operator. In 1915 he moved to Newark, New Jersey, where he took a job as a darkroom assistant in a portrait studio.

The owner of the studio eventually noticed that Van Der Zee was skilled with a camera. Whenever he had to be away from his establishment, he put Van Der Zee in charge of taking the portraits. Soon customers began to notice that the pictures Van Der Zee took were far better than those taken by the owner.

In 1917, encouraged by this success, Van Der Zee, along with his second wife, Gaynella, opened his own establishment in Harlem, which he named the Guarantee Studio. He could not have chosen a more exciting place or time to launch his own photography career.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, Harlem was a remarkable and important place that would soon have a profound cultural influence throughout the United States and around the world. It was in Harlem that black writers, artists, poets, composers, singers, actors, and musicians gathered together to create what became known as “the cultural capital of black America.” Included among these highly talented people were such writers as Langston Hughes and W. E. B. Dubois, actors such as Paul Robeson, artists such as Jacob Lawrence and William H. Johnson, dancers such as Josephine Baker, and singers and musicians such as Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, and Billie Holiday.

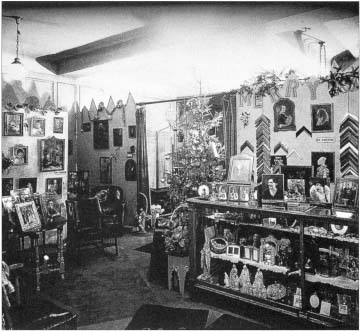

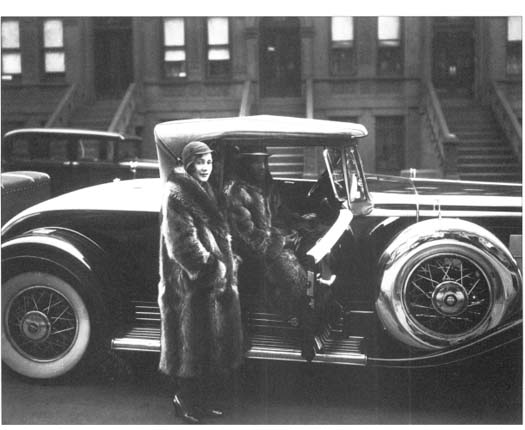

Through pictures like this one of a successful professional dancer, Van Der Zee presented a much different portrayal of African-American life than most white people had seen.

The combination of these enormously creative talents led to such a flowering of African-American artistic expression and social thought that it became known as the Harlem Renaissance. The fact that life in Harlem provided most blacks who lived there with unprecedented independence and freedom of movement led to another important development as well. Thousands of African Americans, inspired by what was taking place in Harlem, began migrating to the industrial centers of the North, especially New York City.

Van Der Zee had opened his Harlem studio in order to earn what he hoped would be a good living. But he also recognized another opportunity. To him, photographing during such a historic time in African-American experience presented the chance to reveal through his pictures a different class of black people, more cultured and much more successful, than was commonly portrayed.

The studio itself reflected his goal of introducing the nation to a new type of black American. Unlike almost any other photography establishment that catered to blacks, it was elegantly adorned with expensive chairs, tables, drapes, floral arrangements, and richly illustrated backdrops.

Even more important was the care with which he took his pictures. Unlike most other portrait photographers of his day, Van Der Zee was intent on not merely producing a perfect likeness of his subjects but on capturing what it was that made each person who sat for him distinct. “I posed everybody according to their type and personality, and therefore almost every picture was different,” he would later state. “In the majority of studios, they just seem to pose everybody according to custom, according to fashion, and therefore the pictures seem to be mechanical looking to me … I tried to pose each person in such a way as to tell a story.”

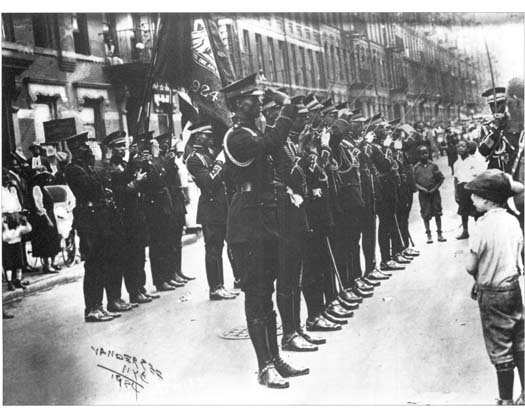

Harlem was home to African Americans with diverse talents and beliefs, including members of a black Jewish congregation whom Van Der Zee photographed in front of their synagogue.

Such dedication was grueling. Van Der Zee spent so much time posing and lighting each subject that he often could not produce more than three or four pictures that satisfied him in a day. But his commitment to his goal paid off. The men and women of Harlem—both unknown citizens and celebrities—flocked to his studio. Van Der Zee photographed them all, including society ladies in their beautiful clothes, wedding parties, and family groups. Among the scores of African-American celebrities who sat before his camera were heavyweight-boxing champion Jack Johnson, famed dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and the Reverend Adam Clayton Powell.

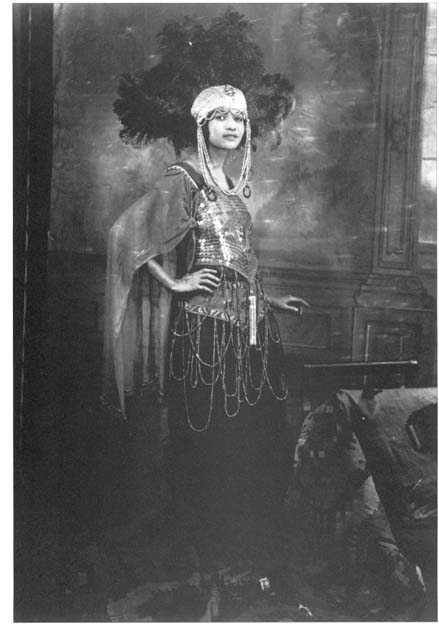

Van Der Zee was fascinated with the controversial African-American leader Marcus Garvey and took many pictures of him and his dedicated followers.

Van Der Zee’s celebrity portraits resulted in nothing less than a gallery of black achievement and pride. Equally important were the thousands of photographs he took outside his studio. The dedication he displayed in taking his portraits was now brought to the streets and buildings of Harlem. There he captured the life of the forty-five-block city district in all its various aspects. He took pictures of parades, men’s and ladies’ social clubs, schoolchildren, and business, sports, and civic activities.

Some of his photographs were of unique subjects, such as those he took of black Jews who lived and worshiped in Harlem. Van Der Zee was also fascinated by the elegant funeral ceremonies that were part of Harlem life and produced a series of photographs depicting the rituals that accompanied these events. The series, which revealed the special spiritual values that African Americans placed on funerals, was eventually published in a book titled The Harlem Book of the Dead.

Van Der Zee also captured many images of Marcus Garvey, the most influential African-American leader of the 1920s. Head of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, whose goals included that of promoting the spirit of black pride, Garvey chose Van Der Zee to chronicle the activities of his organization.

Among Van Der Zee’s pictures were two that, in the view of many photography critics, epitomize his success in counteracting the false and harmful depictions of African Americans so prevalent in his time. In 1932 he took a photograph of a pair of Harlem’s fashionable citizens and their new automobile, which he titled “A Couple Wearing Raccoon Coats with a Cadillac.” The luxurious shiny vehicle, the couple’s expensive fur coats, and their proud, confident expressions create a portrait that is the personification of the energy and optimism of the Harlem Renaissance.

For most of his career Van Der Zee worked in relative obscurity, but after his 1969 Harlem on My Mind exhibition many of his photographs, particularly this one, began to be included in photography shows.

In this photograph of a Harlem couple on their wedding day, Van Der Zee inserted a ghostly image of a child to suggest the happy family life that he wished for the newlyweds.

This photograph of an African-American singing group rehearsing was typical of pictures Van Der Zee took to document the creativity and vitaliy that characterized Harlem during the 1920s and ‘30s.

Van Der Zee’s photograph “Wedding Day” reveals his desire to convey the importance of family values in the Harlem community. It is an image that also reveals his commitment to depicting African Americans as cultured and refined people.

By the time World War II ended in 1945, James Van Der Zee had been taking pictures for more than forty-five years. His portrait business in particular had earned him a better living than he might have once imagined. But with the end of the war came the introduction of efficient, easy-to-use personal cameras. People had much less need for professional studio portraits, and Van Der Zee’s fortunes declined dramatically. In order to support himself, he was forced to shoot passport photos and to search for other photography jobs. At the same time, the glory days of Harlem came to an end.

During the next two decades things got even worse for Van Der Zee. By 1967 his work had fallen into obscurity, he had lost his studio, and he and his wife were living in poverty. In that same year, however, a photo researcher at the Metropolitan Museum of Art stumbled upon tens of thousands of Van Der Zee’s photographs that had been given to the museum. In 1969 the Metropolitan staged a major exhibition titled Harlem on My Mind, which featured many of the images the researcher had found. Almost overnight Van Der Zee began to receive national attention, and his fortunes were reversed once again.

Harlem on My Mind had another result as well. During its three-month run, it drew more viewers than almost any other exhibition in the museum’s history. Most visitors were white, but for the first time African Americans came to the Metropolitan not as janitors or other menial laborers but as patrons.

Although Van Der Zee was now eighty-two years old, the attention and acclaim that Harlem on My Mind brought him rekindled his career. Just as, some sixty years before, famous African Americans had flocked to his studio, modern-day black celebrities now sought him out to have their pictures taken, including such highly respected people as Muhammad Ali, Bill Cosby, Cicely Tyson, Ossie Davis, and Ruby Dee.

At ninety-two, Van Der Zee found himself still in demand. “The body wears out,” he told a reporter, “but the mind doesn’t need to.” In his final years he received many honors. He was awarded two honorary doctorate degrees and was named an Honorary Fellow for Life by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He was also invited to the White House, where he was presented with the Living Legacy Award by President Jimmy Carter.

James Van Der Zee died in 1983 at the age of ninety-six. He had taken close to a hundred thousand photographs in a career that spanned more than eighty years, one of the longest in the history of photography. Yet it was what these pictures conveyed that was his great legacy. By producing images of a people and a culture in transition, he helped change whites’ attitudes about African Americans and what they could achieve. As one photography critic has stated, “It’s hard to see Harlem through any other eyes.”

Van Der Zee would not snap his shutter until he was completely satisfied that the image, such as this classroom shot, captured exactly what he wanted it to say.