18

ELECTORAL INTEGRITY

Over the course of the past decade a new sub-field of study has emerged on the topic of electoral integrity, which can be broadly defined as the overarching practical and normative context within which elections occur. This chapter reviews the growth of this literature to show how it departs from traditional approaches to understanding electoral behavior and institutions. In particular it highlights the commitment of scholars to a more normative, problem solving, and policy relevant agenda. After contextualizing this new body of work within the wider academic canon the chapter moves on to discuss how electoral integrity can be operationalized and sets out the key criteria that measures of electoral integrity need to meet in order to be considered valid and reliable. The final section of the chapter summarizes recent empirical work demonstrating the importance of perceptions of electoral integrity for levels of popular trust and confidence in the political system, and also for turnout and protest activity. The conclusion identifies the next steps for moving the contemporary research agenda on electoral integrity forward.

Conceptualizing electoral integrity

Electoral integrity can be conceived in several ways. The key difference centers on whether it is understood negatively or positively (van Ham 2015). On the former front studies have typically focused on whether contests are “manipulated” (Schedler 2002; Simpser 2013), “fraudulent” (Lehoucq and Jiménez 2002; Vickery and Shein 2012) or characterized by “malpractices” (Birch 2010). The latter more positive accounts center on whether elections can be considered as “free and fair” (Bjornlund 2004; Elkit and Reynolds 2005; Lindberg 2006; Goodwin-Gill 2006; Bishop and Hoeffler 2014), “genuine and credible” (observer reports), “competitive” (Hyde and Marinov 2012), or “democratic” (Munck 2009; Levitsky and Way 2010).

A human rights understanding of electoral integrity, and the preferred approach of this chapter, adopts this latter more positive stance and argues that it exists when electoral procedures meet agreed international conventions and global norms covering the full election cycle – that is, from the pre-election period, through to the campaign, polling day, and the immediate aftermath (Norris 2013, 2014, 2015). These conventions and norms are typically contained in written declarations, treaties, protocols, case law, and guidelines issued by inter-governmental organizations, and endorsed by member states worldwide. While some of these conventions are legally binding under international law, others are more customary in nature but in effect have the same compulsory status.

Article 21(3) of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights is widely seen as providing the cornerstone of the legal definition of electoral integrity. Namely that

The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government: this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.

This framework was further developed through Article 25 of the 1966 UN International Convention for Civil and Political Rights. Since then, a series of conventions endorsed by member states of the United Nations and inter-governmental regional organizations such as OSCE and OAS have extended the framework to outlaw any form of discrimination based on race, sex, or disability.1

The growth of electoral integrity research agenda

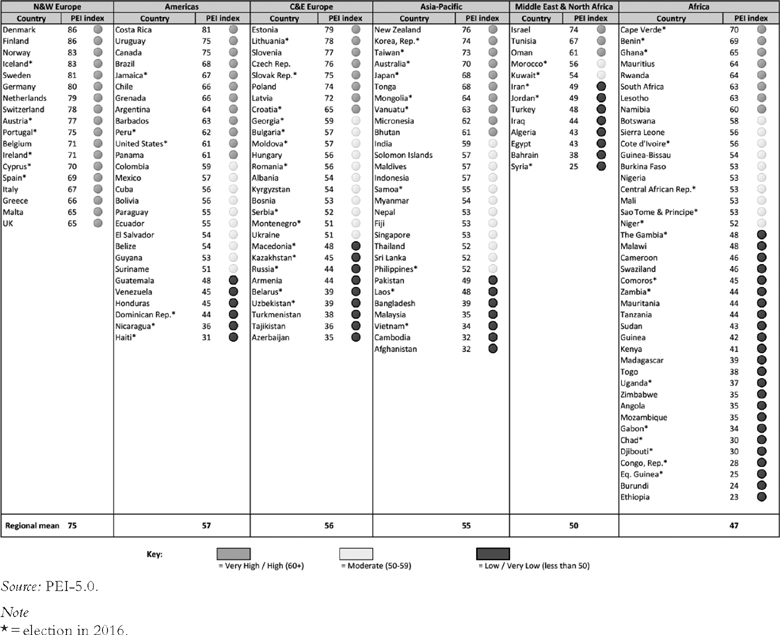

A key driver behind the rise of the electoral integrity research agenda has been the surge in the use of elections around the world. Banks’ Cross-National Time-Series dataset reports that, at the end of World War II, around 50 independent nation-states had a popularly elected legislature. This number has now roughly quadrupled (see Figure 18.1). With some exceptions, therefore,2 almost all independent nation-states around the world now hold multi-party elections for the lower house of the national parliament.

Figure 18.1 The growing number of elected national legislatures, 1815–2007

Source: Arthur Banks Cross-National Time-Series Dataset 1815–2007.

Electoral malpractices under autocracies

This diffusion of elections worldwide has led to burgeoning literature on the way these contests work (or fail to do so) in autocratic states. In the heyday of the Soviet Union, contests for the Duma were infrequent phenomenon with few significant consequences beyond conferring a patina of legitimacy upon Communist parties. By contrast, the last decade has seen rapidly growing interest in the role and function of electoral institutions in authoritarian states. Debate has centered on the consequences of multi-party elections for democratization with some scholars such as Lindberg (2006) arguing that they offer important opportunities for opposition parties to organize and mobilize support. Others such as Carothers (2002) have warned against assuming that elections inevitably lead to a progressive transition toward democracy. Recent evidence of an authoritarian push-back against democracy and signs that it may be “in retreat” (Kurlantzick 2014) or “in decline” (Diamond and Plattner 2015) are seen as supporting this more pessimistic view.

Recognition of this new constitutional fluidity has led scholars to abandon the dichotomous regime typologies developed by Przeworski et al. (2000) and since updated by Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland (2010) in favor of more flexible schemas that focus on the intermediate or gray zone between democracy and autocracy. These efforts have resulted in identification of a more mixed set of regime types including “electoral democracies,” “semi-democracies,” and “semifree” regimes (Freedom House 2017). Elsewhere, scholars have avoided references to democracy, preferring to talk about “hybrid states” (Diamond 2002), “anocracies” (Polity), or “electoral” or “competitive” autocracies. (Schedler 2006; Levitsky and Way 2002, 2010). Several sub-types have also been distinguished among the latter – for example, Magaloni (2006) draws a line between “hegemonic-party autocracies,” which are thought to differ from military regimes and personal dictatorships.

The growth of these new hybrid states poses many new and interesting questions for scholars of elections, public opinion and parties. In particular they challenge the focus of conventional electoral behavioral research on the micro-level modeling of individual voter decision making and shift attention toward the role of broader contextual factors in explaining both elite and mass activities. Why, for example, would the ruling parties in these states allow any contests to occur given the risks they pose for destabilizing their power base? Why would the citizens living under these autocratic conditions actually turn out to vote in the first place? Finally, how can we explain popular support for hegemonic parties?

Electoral maladministration in democracies

A second factor that has prompted academic interest in questions of electoral integrity has been the growing recognition of problems in the regulation and administration of electoral procedures in established democracies. Concern over the performance of elections in Western democracies, and interest in policy reforms designed to strengthen the electoral process, have grown over the past quarter century. Since the 1990s several major reforms of electoral systems have been undertaken in many long-established democracies, such as Italy, Japan, and New Zealand (Renwick 2010). There have also been numerous legal and regulatory reforms imposed on various aspects of the electoral process such as campaign finance, term limits, direct democracy initiatives, and convenience voting procedures that have prompted scholarly attention in terms of analyzing their causes and effects (Bowler and Donovan 2013; Norris and Abel van Es 2016).

Within the US there has been a longstanding tradition of academic research into the impact of varying state-level registration and voting procedures on voter turnout (Rosenstone and Wolfinger 1978; Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980). Scrutiny of these procedures, however, increased dramatically following the Florida presidential vote count in 2000, which provoked a heated and heavily polarized debate over the fairness and integrity of US elections. The irregularities identified in the voting process prompted a series of major legal challenges and highprofile accusations of voter fraud against the Republican winner, George W. Bush. The 2014 report of the bipartisan Presidential Commission on Election Administration did little to calm these fears, setting out a long list of vulnerabilities in American elections (Bauer et al. 2014). Growing anxieties over the contemporary quality and performance of US electoral laws can also be seen in the number of recommendations being put forward for practical reforms of state and local public administration (Alvarez and Grofman 2014; Cain, Donovan, and Tolbert 2008; Hasen 2012; Streb 2004). It has also prompted action by state legislatures with controversial new laws being introduced typically under Republican majorities, designed to tighten the security of voter registration and balloting identification requirements. Such measures have since been copied by right-wing governments in other countries, leading to partisan battles over the “Fair Votes” Act in Canada and heated debate over the introduction of new individual voter registration procedures in the UK. These developments clearly present challenges to conventional studies of voting behavior in these countries in that they add in a new context and criteria to the choices being made. More specifically, how does one interpret a vote decision in the context of flawed and even failed election?

Electoral integrity and traditional studies of voting behavior

As the previous section suggests, the rapid changes and concerns arising in the electoral landscape of so many nations has meant that studies of voting behavior have struggled to keep pace with, and explain, recent developments. Much of the empirical research on elections and voting behavior from the mid-twentieth century onward has been conducted within a paradigm of scientific neutrality. Institutional studies of electoral reforms have come perhaps closest intellectually to the integrity paradigm, although these accounts typically seek to classify rules and explain procedural changes and their consequences from a neutral or relativistic standpoint, rather than explicitly advocating any single “best” system (Colomer 2004; Gallagher and Mitchell 2005; Renwick 2010). Academic engagement in normative debates about how elections should work and what policy reforms might help them perform better has thus been largely avoided. Micro-level studies of voter attitudes and behavior in established and newer democracies in particular have generally displayed very little interest in citizens’ evaluations of the integrity of electoral processes and how this might influence voting choices and participation. Any problems arising from electoral malpractices have typically been left to legal scholars, historians, and policy analysts to analyze. Evidence of this lack of attention is evident from only a brief look at a wide range of cross-national surveys and national election studies. Items measuring trust and confidence in electoral procedures and authorities are rarely included on any regular basis.

By contrast, accounts within the electoral integrity perspective typically adopt an overtly critical and normative stance to the topic. Scholars typically begin with an explicit recognition that electoral procedures in many contests fail to meet certain desirable standards of human rights. This is then followed by the realization that these flawed and failed contests have important consequences for citizens and regimes. Analysis and conclusions then center on identifying the reforms of public policies and administrative procedures that are necessary to address these problems (Norris 2014, 2015).

Measuring electoral integrity

Given its breadth and complexity as a concept, operationalizing and measuring electoral integrity presents a challenging task. However, recent efforts have shown that it can be operationalized in ways that are precise, valid, and reliable (Norris 2013; van Ham 2015). The approaches that have been taken to date in measuring electoral integrity can be broadly divided into two types – those that utilize mass survey data and those relying on expert judgments.

Mass level studies

As noted earlier, measures of electoral integrity at the mass level are rare, particularly in crossnational studies and in repeated or longitudinal manner. The first wave of CSES in the mid1990s monitored citizens’ assessment of “free and fair” elections (Birch 2008, 2010). However, this item was not asked in subsequent waves of the study. Similarly isolated items about attitudes toward free and fair elections have fielded in the Global-barometers and the ISSP surveys, as well as in specific national election studies in countries such as Russia and Mexico. More promisingly, however, since 2005, the Gallup World Poll has regularly asked the public in over 100 societies around the world about the honesty of elections in their country. Most recently the sixth wave of the World Values Survey (2010–2014) carries the most extensive battery of nine items monitoring perceptions of electoral integrity and malpractices in around forty societies (Norris 2014).

Elite level studies

A more common approach to measuring electoral integrity is one that relies on expert judgments. Of these, the Freedom House and Polity IV indices are probably among the most widely used and recognized. These indices are designed to measure the level of democratization or democratic performance of a nation writ large rather than the quality of its electoral practices specifically. While there is clearly an argument for some linkage between the democratic status of a nation and the standard of its elections, as the evidence has increasingly shown there are cases where the two diverge and the former cannot form a proxy for the latter. Thus, these standard measures need some further nuancing and disaggregation.

The Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index

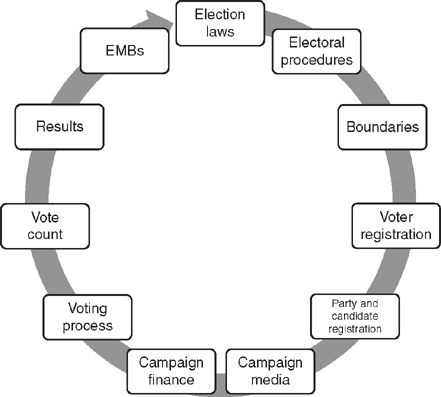

The Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index helps to fill this gap. The index emerged from the Electoral Integrity Project as a new tool to measure electoral practices worldwide. The index, fielded annually since 2012, uses expert evaluations to measure the perceived quality of elections. It is based on the central premise that elections can be broken down into eleven key sequential and inter-related steps. These are represented in Figure 18.2.

Like complex links in a chain, violating international standards at any one step in the process throws into question the integrity of the whole electoral process. Thus, rather than focus on particular acts of electoral fraud such as the occurrence of multiple voting or stuffing of ballot boxes, as previous indices have done, the PEI index captures multiple points where fraud and manipulation can occur. This can range from the drawing of district boundaries to advantage a particular party or candidate, to generating false criminal charges to disqualify opponents. Unequal access to media and money can also act as a significant and less visible barrier to open selection of candidates. Finally, once the results are announced, lack of impartial adjudication to resolve any disputes can trigger protest and violence.

Figure 18.2 The stages in the electoral integrity cycle

The breadth and flexibility of the PEI index means that analysts are able to disaggregate it and pinpoint the issues that they regard to be of most concern in each context. This might involve a focus on the impartiality of the electoral authorities, equitable access to resources during campaigning, or conflict flaring up in the aftermath of the results. In addition, the PEI measures electoral integrity on a continuum rather than by adopting an arbitrary cut-off point. If need be, however, it can be calibrated to the mean to produce categorical distinctions of flawed contests (elections with moderate integrity) and failed contests (ranked lowest on the index). The PEI can also accommodate contests with varying degrees of electoral competition. Thus it can be used to measure integrity in national elections in one-party states such as Cuba where all opposition parties are banned, or where one specific type of party is restricted from ballot access, such as the Freedom and Justice Party in Egypt. It can also be applied to contests where restrictions on individual candidates standing are applied through vetting processes such as in Iran.

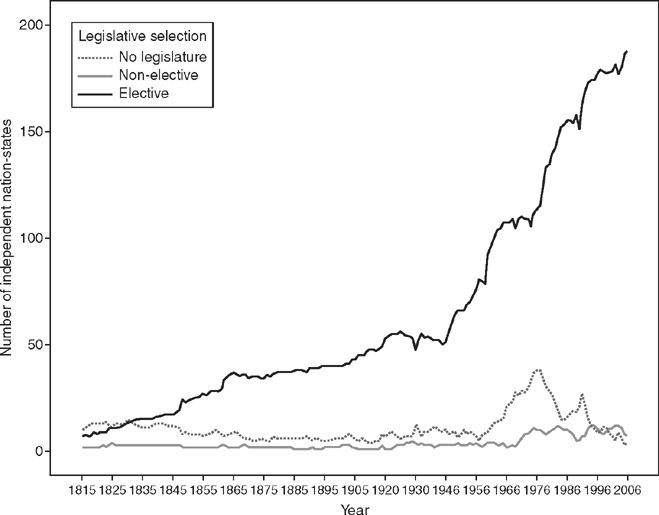

Data collection, as stated above, involves completion of a survey by a cross-section of electoral scholars with country-specific expertise.3 Each of the eleven stages of the electoral process are broken down into more specific domains of activities and respondents are then asked to evaluate the perceived quality of practice in each domain. Findings from the first wave of the PEI (2012–2016) for the 153 countries holding national elections from mid-2012 to mid-2016 are presented in Table 18.1.

The results point to some expected global patterns in that many long-established democracies score well, especially countries in Scandinavia and Western Europe. Countries in the Middle East and Africa generally register much lower scores, as do many countries in the Asia-Pacific region and also in Central Asia. There are also some interesting findings among the more established democracies that underscore the evidence presented earlier about growing problems of electoral legitimacy in these nations. In particular, the United States and the United Kingdom both perform relatively poorly while many of the states in Central and Eastern Europe and the Baltics achieve comparatively healthy scores, as do several countries in Latin America, such as Costa Rica and Uruguay. There is, however, a wide dispersion around the mean in both of these regions.

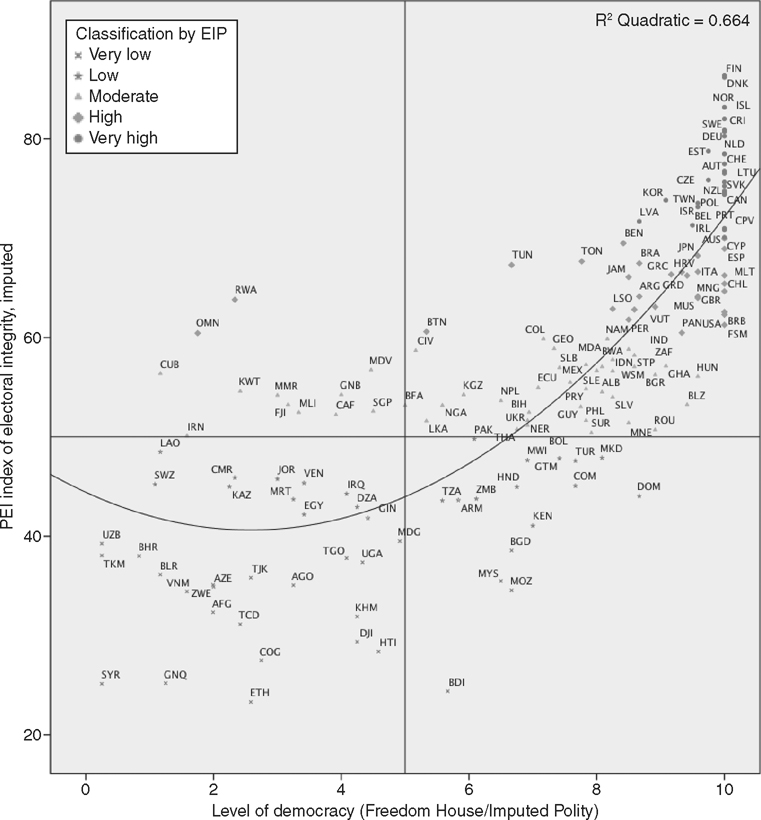

As a final step to indicate the robustness of the PEI index we correlate the scores it produces against those generated through the alternative democratization indices discussed above. The results are reported in Figure 18.3.

The figure confirms that a significant degree of overlap exists across the indices but also reveals some important differences in the scores produced. Specifically we see a strong correlation in the top right-hand quadrant which confirms that more democratic states typically display more electoral integrity. A similar clustering exists in the bottom left-hand quadrant showing that autocratic states have a higher incidence of electoral malpractices as we might expect. However, it is also clear that there are many democratic states located in the bottom right handquadrant, meaning they report low levels of electoral integrity. The findings thus support the contention that the PEI index is not simply a proxy for regime type and that it can discriminate subtle but important differences in the quality of elections worldwide.

Figure 18.3 Comparing electoral integrity and democratization

Sources: Freedom House/Imputed Polity Quality of Government dataset; Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI 4.5), http://www.electoralintegrityproject.com.

Does integrity matter for political attitudes and voting behavior?

Repeated application of the PEI will provide the basis for examining important research questions central to many sub-fields of political science. For instance, do certain problems surface more frequently under particular regime types? When are malpractices most likely to occur in the electoral cycle? What are the structural, international, and institutional factors that drive flawed and failed contests (Norris 2015)? Finally, and perhaps most importantly, what can be done to fix failed elections? In developing this new research agenda it is important to establish what insights and conclusions existing empirical analyses of electoral integrity have drawn. In this final section of the chapter, therefore, a summary of the main questions and findings that this more applied work has generated is presented.

To date, while some attention has been given to specific events or actors within the electoral integrity cycle, such as the impact of international monitors on polling place fraud and ballot stuffing (Hyde 2011; Kelley 2012; Donno 2013), most of the empirical work on the topic has centered on the extent to which citizens’ views of their electoral system affects levels of democratic legitimacy within a society. This is typically measured through indicators such as decreases or increases in levels of trust in the authorities and/or behavioral support for the system in terms of voter turnout. Such studies have been undertaken as large N comparative analyses (Birch 2010; Norris 2014) as well as more focused regional and national studies. On the latter front this has included studies of the usual suspects in North America and Western Europe. For example shortcomings in electoral laws and voting procedures were shown as lowering turnout in several American states (Burden and Stewart 2014; Alvarez and Grofman 2014). Furthermore the depressive effect of perceived malpractices was found to be particularly strong among African-American voters. In Western Europe, studies by Anderson and Tverdova (2003) and Gronlund and Setala (2011) found that perceptions of bribery and corruption generally depressed trust in political institutions.

Elsewhere, studies of African electorates have found that those who express greater confidence in the quality of their elections are more likely to give positive evaluations of democratic performance and to believe in the legitimacy of their regime (Moehler 2009; Robbins and Tessler 2012; Bratton 2013). In their analysis of Sub-Saharan Africa, Bratton and de Walle (1997) found that perceptions of the quality of elections were positively associated with voter turnout in a number of states. Moving to the Latin American region, McCann and Dominguez (1998) examined a series of public opinion polls in Mexico in the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, a period of one-party rule by the PRI. They found that those citizens expecting electoral fraud were more likely to stay at home on election day, and this group was also more likely to support the opposition. Work by Simpser (2012) confirmed these conclusions through analysis of aggregate turnout data in the pre and post-reform eras. Finally these relationships have also been seen to hold among Eastern European voters. Rose and Mishler (2009), for example, report that Russians who thought that the Duma elections were unfair were less likely to express national pride, as well as proving more mistrusting of parties and parliament, and less likely to endorse the regime.

Looking beyond these conventional measures of democratic legitimacy, other studies have shown how general mistrust in electoral processes can have a contrary effect on less institutionalized methods of participation and particularly levels of protest activity. Based on the World Values Survey data in many diverse societies, Norris (2014) found that public perceptions of electoral integrity slightly dampened the propensity to engage in direct action, while perceptions of malpractice strengthened protest activism. Indeed, disaffection with the procedural fairness of elections had a stronger direct effect on protest than standard demographic variables such as age and income and other political attitudes such as dissatisfaction with democracy or confidence in elected institutions.

Overall, therefore, the clear and consistent finding message emerging from contemporary empirical research on electoral integrity, and one that future studies can build on, is that mass perceptions of the fairness of elections matter for electorates’ behavior and attitudes. This appears to hold regardless of regional context and the distinctiveness of local political culture.

Conclusions

The concept of electoral integrity can be seen as having introduced a new contextual and individual level variable relevant for models of political behavior. In doing so it has supplemented and enriched longstanding approaches to electoral research, and extended their normative and policy relevant quality. On the former front it offers the potential for fresh analytical insights into many classic issues, including how formal procedures shape party choice and turnout in voting behavior, and what determines citizens’ confidence and trust in political authorities and satisfaction with democracy? On the latter front, the introduction of the concept has also raised important normative debates about the most desirable qualities of elections and policy-relevant questions about how to reform malpractices both at home (Bauer et al. 2014) and abroad (Bowler and Donovan 2013). The radical paradigm developing around issues of electoral integrity is still in the process of coalescing, but it promises to shake up a half century of electoral studies and political behavior. By addressing contemporary real-world problems well beyond academe, the emerging sub-field holds considerable promise of dissolving conventional divides between the practitioner and scholar and breaking down intellectual walls separating scholars of the West and the rest. Finally, from a disciplinary perspective, the electoral integrity agenda also has the potential to challenge the boundaries that typically characterize political science research, and forge a new and exciting interface between scholars of public administration, political participation, international relations, normative political theory, and comparative institutions.

Notes

1Legally-binding commitments and state ratifications have been collated by Tuccinardi (2014) for International IDEA and codified in an integrated Elections Obligations and Standards (EOS) database maintained by The Carter Center. Elections Obligations and Standards Database. http://electionstandards.cartercenter.org/tools/eos/.

2Only a handful of contemporary autocracies (including Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Brunei) lack constitutional provisions for any direct elections to the lower house of the national parliament. In some cases, like Thailand, elections are currently suspended by the military junta, although promised to be restored eventually. A few one-party states remain, exemplified by China, Vietnam, North Korea, and Cuba, where only Communist party members can hold national legislative office. A few other states, such as Bahrain and Kuwait, also ban all political party organizations by law, although they allow “societies” or “blocs” and individual candidates to run for office. Other countries ban specific parties, such as the courts in Sisi’s Egypt, which outlawed the Freedom and Justice Party, the Muslim Brotherhood’s political wing.

3The survey asks around forty electoral experts from each country, generating a mean response rate of around 28 percent across the survey with replies in PEI 4.5 from 2,417 experts covering 213 elections.

References

Alvarez, R. M. and Grofman, B. (eds.) (2014) Election Administration in the United States: The State of Reform after Bush v. Gore, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, C. J. and Tverdova, Y. V. (2003) “Corruption, Political Allegiances, and Attitudes Toward Government in Contemporary Democracies,” American Journal of Political Science, vol. 47, no. 1, January, 91–109.

Bauer, R. F., Ginsberg. B. L., Britton, B., Echevarria, J., Grayson, T., Lomax, L., Coleman Mayes, M., McGeehan, A., Partick, T., and Thomas, C. (2014) The American Voting Experience: Report and Recommendations of the Presidential Commission on Election Administration, Washington DC: Presidential Commission on Election Administration.

Birch, S. (2008) “Electoral Institutions and Popular Confidence in Electoral Processes: A Cross-National Analysis,” Electoral Studies, vol. 27, no. 2, June, 305–320.

Birch, S. (2010) “Perceptions of Electoral Fairness and Voter Turnout,” Comparative Political Studies, vol. 43, no. 12, December, 1601–1622.

Bishop, S. and Hoeffler, A. (2014) “Free and Fair Elections: A New Database,” Working Paper, Center for the Study of African Economies (CSAE), University of Oxford.

Bjornlund, E. C. (2004) Beyond Free and Fair: Monitoring Elections and Building Democracy, Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Bowler, S. and Donovan, T. (2013) The Limits of Electoral Reform, New York: Oxford University Press.

Bratton, M. (2013) Voting and Democratic Citizenship in Africa, Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Bratton, M. and van de Walle, N. (1997) Democratic Experiments in Africa: Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Burden, B. C. and Stewart, C. III (eds.) (2014) The Measure of American Elections, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cain, B. E., Donovan, T., and Tolbert, C. (2008) Democracy in the States: Experimentation in Election Reform, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Carothers, T. (2002) “The End of the Transitions Paradigm,” Journal of Democracy, vol. 13, no. 1, January, 5–21.

Cheibub, J. A., Gandhi, J., and Vreeland, J. R. (2010) “Democracy and Dictatorship Revisited,” Public Choice, vol. 143, no. 2, April, 67–101.

Colomer, J. M. (2004) Handbook of Electoral System Choice, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Diamond, L. (2002) “Thinking About Hybrid Regimes,” Journal of Democracy, vol. 13, no. 2, April, 21–35.

Diamond, L. and Plattner, M. F. (eds.) (2015) Democracy in Decline?, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Donno, D. (2013) Defending Democratic Norms, New York: Oxford University Press.

Elklit, J. and Reynolds, A. (2005) “A Framework for the Systematic Study of Election Quality,” Democratization, vol. 12, no. 2, April, 147–162.

Freedom House (2017) www.freedomhouse.org.

Gallagher, M. and Mitchell, P. (eds.) (2005) The Politics of Electoral Systems, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goodwin-Gill, G. S. (2006) Free and Fair Elections, 2nd Edition, Geneva: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Gronlund, K. and Setala, M. (2011) “In Honest Officials We Trust: Institutional Confidence in Europe,” American Review of Public Administration, vol. 42, no. 5, September, 523–542.

Ham, C. van (2015) “Getting Elections Right? Measuring Electoral Integrity,” Democratization, vol. 22, no. 4, June, 714–737.

Hasen, R. L. (2012) The Voting Wars: From Florida 2000 to the Next Election Meltdown, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hyde, S. D. (2011) The Pseudo-Democrat’s Dilemma, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Hyde, S. D. and Marinov, N. (2012) Codebook for National Elections Across Democracy and Autocracy (NELDA) 1945–2010, Version 3, available online: www.nelda.co/NELDA_codebook_2012.pdf.

Kelley, J. (2012) Monitoring Democracy: When International Election Observation Works and Why It Often Fails, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kurlantzick, J. (2014) Democracy in Retreat: The Revolt of the Middle Class and the Worldwide Decline of Representative Government, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lehoucq, F. E. and Jiménez, I. M. (2002) Stuffing the Ballot Box: Fraud, Electoral Reform, and Democratization in Costa Rica, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Levitsky, S. and Way, L. A. (2002) “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism,” Journal of Democracy, vol. 13, no. 2, April, 51–66.

Levitsky, S. and Way, L. (2010) Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lindberg, S. (2006) Democracy and Elections in Africa, Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Magaloni, B. (2006) Voting for Autocracy: Hegemonic Party Survival and Its Demise in Mexico, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCann, J. A. and Dominguez, J. I. (1998) “Mexicans React to Electoral Fraud and Political Corruption: An Assessment of Public Opinion and Voting Behavior,” Electoral Studies, vol. 17, no. 4, December, 483–503.

Moehler, D. C. (2009) “Critical Citizens and Submissive Subjects: Elections Losers and Winners in Africa,” British Journal of Political Science, vol. 39, no. 2, April, 345–366.

Munck, G. L. (2009) Measuring Democracy: A Bridge Between Scholarship and Politics, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.

Norris, P. (2013) “Does the World Agree About Standards of Electoral Integrity? Evidence for the Diffusion of Global Norms,” Electoral Studies, vol. 32, no. 4, December, 576–588.

Norris, P. (2014) Why Electoral Integrity Matters, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, P. (2015) Why Elections Fail, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, P. and A. Abel van Es. (2016) Checkbook Elections, New York: Oxford University Press.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M. E., Cheibub, J. A., and Limongi. F. (2000) Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Renwick, A. (2010) The Politics of Electoral Reform, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Robbins, M. D. H. and Tessler, M. (2012) “The Effects of Elections on Public Opinion Towards Democracy: Evidence from Longitudinal Survey Research in Algeria,” Comparative Political Studies, vol. 45, no. 10, October, 1255–1276.

Rose, R. and Mishler, W. (2009) “How Do Electors Respond to an “Unfair” Election? The Experience of Russians,” Post-Soviet Affairs, vol. 25, no. 2, April, 118–136.

Rosenstone, S. J. and Wolfinger, R. E. (1978) “The Effect of Registration Laws on Voter Turnout,” American Political Science Review, vol. 72, no. 1, March, 27–45.

Schedler, A. (2002) “The Menu of Manipulation,” Journal of Democracy, vol. 13, no. 2, April, 36–45.

Schedler, A. (ed.) (2006) Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition, Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Simpser, A. (2012) “Does Electoral Manipulation Discourage Voter Turnout? Evidence from Mexico,” Journal of Politics, vol. 74, no. 3, July, 782–795.

Simpser, A. (2013) Why Parties and Governments Manipulate Elections: Theory, Practice and Implications, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Streb, M. J. (ed.) (2004) Law and Election Politics, 2nd Edition, New York: Routledge.

Tuccinardi, D. (ed.) (2014) International Obligations for Elections: Guidelines for Legal Frameworks, Stockholm: International IDEA.

Vickery, C. and Shein, E. (2012) Assessing Electoral Fraud in New Democracies, Washington, DC, IFES, available online: www.ifes.org/sites/default/files/assessing_electoral_fraud_series_vickery_shein_0.pdf.

Wolfinger, R. E. and Rosenstone, S. J. (1980) Who Votes? New Haven: Yale University Press.