34

GENERATIONAL REPLACEMENT

Introduction

Generational replacement is one of the most important drivers of social and political change. This is because values and voting habits are acquired early in life and then remain relatively stable over time. The older people become, the more they tend to get “set in their ways” (Franklin 2004) and the less likely they are to change their habits, basic values and attitudes. Political events thus exert the strongest impact on the youngest voters who are not yet “set in their ways.” To the extent that political attitudes and behavioral habits are acquired early in life during the most “formative years,”1 and remain stable afterwards, generational replacement is the main driver of change. It works a bit like a diesel engine. It has a slow start, but continues to run for a long time.

To be clear, the habits we are talking about are not immutable. Having a “habit of voting” does not mean that one will turn out to vote at every election, and being a “habitual party supporter” does not mean that one will invariably support that party. Rather these habits provide a “home base” to which people generally return after any defection from behavior that conforms to the habit concerned.

In order to study the impact of generational replacement, one has to disentangle three types of effects, which all contribute to change over time: (1) life-cycle effects, which are changes that take place as a result of growing older, (2) cohort effects, which are stable differences between generations, and (3) period effects, which are social developments and events that potentially exert an effect on all generations and age groups (though perhaps not equally). While social scientists have long been aware of the importance of generational replacement as a driver of social change, most political scientists tend to ignore it because for several reasons it is notoriously difficult to study. The first is the fact that life-cycle effects, period effects and birth cohort effects are so highly interconnected that they are (statistically) difficult to disentangle. The year in which one was born follows logically from the combination of the year in which a survey was conducted and the age of the respondent.2 So the only way to statistically disentangle the three effects is to estimate them while making one or more restrictions to the model – for instance, by assuming a linear effect of age and/or by clustering groups of respondents into larger “birth cohorts.”

The second (albeit related) problem is a data issue. Ideally one would want panel data spanning several decades to study the stability and change of behaviors and attitudes at the individual level. A few such long-running panels exist (e.g., the British and German Household Surveys) but these contain few questions of interest to political scientists. Moreover, these long-running panels pose additional challenges, such as panel attrition. Finally, in such a dataset both the youngest and the oldest voters, those of greatest interest in any study of generational replacement, are not present in all waves.3

Because of these problems, scholars usually resort to studies at a more aggregated level, commonly known as cohort-level analyses, which compare aggregate statistics, such as the proportion of respondents with certain characteristics, across different birth cohorts at different moments in time. If the samples are randomly selected and sufficiently large, the assumption is that the subsample of each birth cohort is a representative sample of that generation. So, if a specific birth cohort were to systematically differ from other birth cohorts, controlling for year and age, this would be indicative of a generation effect. These designs require long time series but not panel data, and are thus the most common way to study life-cycle and generation effects. Generations are either defined by historical events that delimit or characterize their formative years (e.g., “the baby boom generation”) or by systematically defined birth cohorts (e.g., born in the 1930s, 1940s, etc.). We focus on the second but mention the first in contexts where other scholars have done so.

The purpose of this contribution is to provide an overview of research on electoral change, with a specific focus on generational replacement. Because of a dearth of studies that take a generational approach to explaining partisanship decline, we include some original research on this topic. We begin with an inventory of the broader field of socialization research, how generations are distinguished and which are the “formative years” before turning to the main dependent variables in electoral research, turnout on the one hand and party support on the other.

Political socialization/learning

One of the most influential studies in electoral research, The American Voter (Campbell et al. 1960), introduced the concept of “Party Identification” (see Chapters 2 and 12 in this volume). The authors of The American Voter assumed that many voters would learn from their parents the values and partisan orientations that would characterize their adult lives – especially the link between social identity and partisanship. Jennings and Niemi (1968) presented convincing evidence in support of this notion, by means of surveys among young people and their parents (see also Jennings and Markus 1984; Jennings 2007). To the extent that people derive their political orientations through parental socialization, they would enter adulthood with established partisan loyalties. In such a world we would not expect there to be much political change. Each generation would have the same basic attitudes as the generations before them. So differences between generations would be small and election outcomes would be stable. This was indeed largely the case in the post-World War II period until the 1960s in most countries, with limited electoral volatility and remarkable stability of party systems, to the extent that these were characterized as “frozen” (Lipset and Rokkan 1967).

Yet, the political protests in the 1960s suggested that a large divide had emerged between the values and political orientations of the generation of post-war baby-boomers and their parents, which inspired new academic interest in the formation of political orientations and in the role of political events therein (for an overview, see Jennings 2007).

An important contribution came from Inglehart (1984), who argued that a widespread value shift was taking place, largely due to generational replacement, with members of the post-war generation prioritizing new concerns, which he called post-materialist values (see Knutsen in this volume). Yet, these shifts do not take place overnight, so he argues. Older generations who grew up in times of economic scarcity and who experienced World War II were more likely to give priority to material values, even after decades of peace and economic growth. A complete transformation of values would have to wait on the complete replacement of contemporary electorates with voters holding post-material values. Though challenging the parental socialization thesis, these findings strongly support the “formative years” hypothesis, which holds that pre- or early adult experiences carry more weight in people’s values than events that occur later in life. It is not entirely clear though which exactly are the “formative years.” Most political scientists tend to see the years of adolescence and early adulthood as the period in life that is most “formative.” Yet, habits of partisanship (for those who did not “inherit” these) evidently can develop later – perhaps considerably later.4

While scholars do not deny that parents still play an important role in the socialization of young children and adolescents, Inglehart made it clear that the post-war generations did not simply “inherit” parental values and loyalties. Instead the dominant pattern found in contemporary research is that such values and loyalties are to a large extent acquired during young adulthood, when attitudes and behaviors are influenced by many from outside the home, such as friends, teachers and the media. Rather than being socialized into certain beliefs before entering the electorate, many citizens now learn their political orientations after having entered the electorate; and behavioral habits (in terms of turnout and party choice) arise from repeated behavioral affirmations (see Dinas 2014 and this volume; Bølstad, Dinas and Riera 2013).5 So there seems to have been a reduction in the importance of parental socialization occurring with generations entering the electorates of their countries after the mid-1960s, with implications for learning processes.

The era of frozen party systems – when most voters supported the party (or parties) of their family’s most salient social identity (generally religion, class or race/ethnicity) – did indeed come to an end in the period concerned, with the United States at the forefront in the 1950s and Italy bringing up the rear in the 1990s (Alford 1963; Franklin, Mackie and Valen 2009).6 Given a lower rate of inherited partisanship, most young voters now spend their first adult decades acquiring one, as we will demonstrate below. So while older voters today are mostly tied to a particular party as “home base,” in much the same ways as in earlier generations, younger voters are much freer to acquire a new partisanship (Gomez 2013), often overriding whatever socialization they may have received from their parents.

We now shift attention to the role of generational change in election outcomes, and focus on the two main dependent variables: turnout and party support.

Turnout and generations

The “engine of generational replacement” is particularly clear in the evolution of long-term change in electoral turnout, which has declined almost everywhere among advanced industrial democracies in recent years. To some extent, this decline is closely linked to the unfreezing of party systems mentioned above. People who are strong supporters of a party tend to vote for that party (Heath 2007), so the decline of partisanship especially among younger voters that occurred in the last quarter of the twentieth century was necessarily associated with a decline in the turnout of those young voters, yielding an overall decline in turnout that was quite marked in some countries, depending on the extent to which party systems moved into a state of flux. The importance of generational change is, however, more easily seen when it comes to institutional changes, such as the abolition of compulsory voting, the lowering of the voting age or the enfranchisement of women.

Figure 34.1 is adapted from Franklin (2004, Figure 3.4). The solid line shows precisely the long-term expectation for turnout evolution following a reform such as the abolition of compulsory voting. For such a reform, we expect an initial drop as all those whose habit of voting is not yet established adjust their turnout to the new situation. This fall is then amplified over time as new cohorts of voters enter the electorate with a level of turnout suited to the new situation. On this graph, two dashed lines show turnout among established voters, unaffected by the change in election law, and among new voters once they become habituated to voting at the new level. The slope that we see occurs because the voters with one level of turnout are being replaced by voters with the other level of turnout. The figure is drawn on the overly simplistic assumption that, beyond the reform election itself (which sees some recently adult voters shifting to the new level), there are no other factors affecting aggregate level turnout. Franklin (2004) demonstrates that the expectation illustrated in Figure 34.1 is largely fulfilled over the countries he was studying.

Figure 34.1 Expected evolution of turnout after the abolition of compulsory voting

As a real-world illustration, Figure 34.2 shows the match found in practice between the expected evolution of turnout depicted in Figure 34.1 and the actual evolution of turnout when we average the turnout seen in the only two countries among (then) established democracies that did abolish compulsory voting during the last half of the twentieth century. As can be seen, there is a good match between the actual turnout, averaged across successive elections before and after a reform occurring at very different times in each country, with turnout expected on the basis of generational replacement (for independent confirmation of the generational basis of Italian turnout decline, see Scervini and Segatti 2012). Prototypical expectations, also fulfilled, for other sorts of electoral reform are shown in Franklin (2004, Figures 3.2 and 3.3) – expectations applying to previously disenfranchised groups, such as 18–21 year olds along with women and immigrants.

Figure 34.2 Expected compared with actual evolution of turnout after the abolition of compulsory voting (average of turnout in the Netherlands and Italy)

Source: IDEA turnout data: Italy 1972 to 2008; Netherlands 1948–2002.

Party support and generational change

Partisanship

The unfreezing of party systems referred to above has resulted in lower overall levels of partisanship (because so many younger voters have not yet acquired one) and higher levels of volatility as younger voters give support to new party offerings, perhaps voting for different parties in successive elections. Nevertheless, this malleability is curtailed as many voters eventually settle down to stable support for a single party, though not necessarily the same party as supported by their parents. Given the link between successive reaffirmations of vote choice and habitual behavior documented in Dinas (in this volume), there should be a relationship between partisanship and age: older voters should be more likely to be partisans, although such age differences may not always have been present.

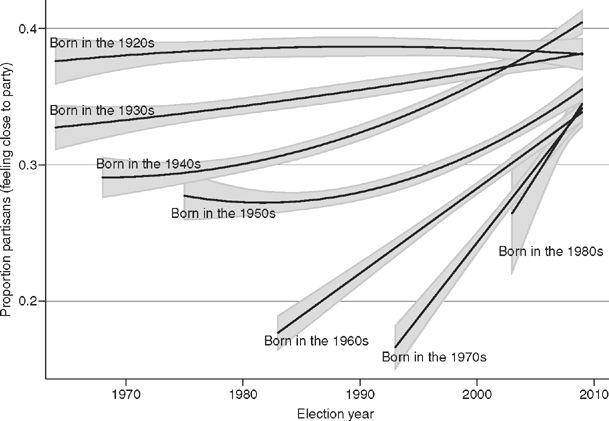

Figure 34.3 shows clearly for a representative group of West European countries that it is quite unlikely for “new voters” in their early 20s and born after the 1950s to report feeling close to a party. Yet, as they grow older, this likelihood increases and there is much less difference between cohorts in the proportion of partisans among those 40 years old and more. The cohort born in the 1950s is the only exception. Apparently this cohort was born into circumstances that came close to matching those of earlier cohorts but then experienced a major period effect while not yet habituated to their initial circumstances, causing them to be transformed from behaving like older cohorts to behaving like younger cohorts, and apparently exemplifying for partisanship the “step” shown for turnout at the reform election in Figure 34.1. Seemingly, before that step was taken, partisanship was largely the result of parental transmission; after that step it had to be learned (we will address the nature of the step later in this section).7

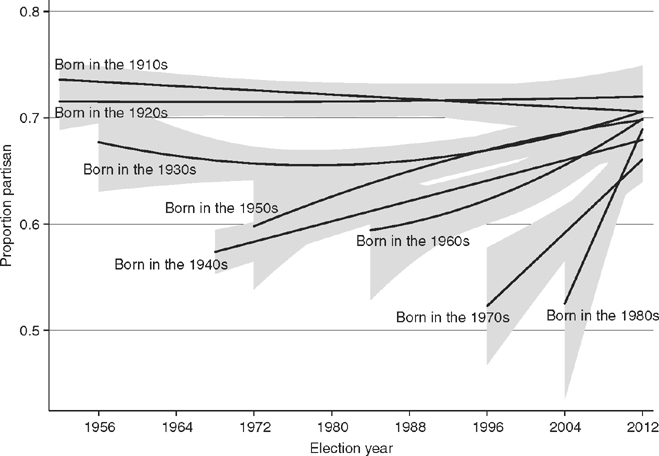

Figure 34.4 shows essentially the same pattern for the United States (the wider confidence intervals are due to the smaller N), though with the period effect associated with the step we just referred to evidently occurring 20 years earlier (see also Alford 1963; Franklin, Mackie and Valen 2009). As in Europe, the patterns in the US suggest that at one time partisanship was passed from parent to child but that, starting in the 1960s, new cohorts began to enter the electorate with much lower partisanship, as reported by Nie, Verba and Petrocik (1979). Although Nie’s study came too early to detect the fact that partisanship then increases with age among the younger US cohorts just as it does in Europe. So both in Europe and in the US there are more weak partisans today than used to be the case because young adults have lower partisanship than used to be the case. We observe the highest degrees of partisanship among the oldest cohorts, both in the US and in Europe (top three lines of both graphs). Cohorts already in the electorate but not well-established (born during the 1950s in Europe; during the 1930s in the United States) lose a degree of partisanship before recovering.8 Later cohorts enter their electorates with ever-lower partisanship scores but nevertheless eventually acquire a degree of partisanship similar to their elders. These are big cohort differences. The idea that change in partisanship has a major generational component was strongly present in Nie, Verba and Petrocik (1979), but more recent literature on partisanship decline, tends to overlook these generational differences.

Figure 34.3 Proportion of Europeans feeling “close” to a party by electoral cohort, 1970–2010

Source: National election studies for a diverse group of European countries (Britain, Germany, Norway, Spain and Sweden), chosen as exemplars with long-running election studies of clear partisanship decline. Shaded areas are 95 percent confidence intervals.

As well as showing very distinct differences between the US and Europe in terms of the timing of partisanship decline our graphs also show differences in the overall strength of partisanship. In the US, the proportion of strong partisans is never less than about 50 percent and appears to rise to some 70 percent among older cohorts. In Europe, the percentage of those feeling close to a party can be little more than 10 percent among the youngest cohorts, rising to only about 40 percent among older cohorts. To some extent, this difference reflects differences in question wording and calibration, but it has also been well-established that party identification as a concept does not travel well from the United States to Europe (Holmberg 2007). In the Netherlands, and also in other multi-party systems, party identification seems rather to be a consequence of party support than a cause (see, for example, Thomassen 1976). Nevertheless, in both the US and in Europe the extent of partisanship remains an excellent indicator of the likelihood that people will (not) switch between parties, as well as of the likelihood that they will vote.

One cannot peruse Figures 34.3 and 34.4 without asking what it was that produced the sea change in the partisanship of post-World War II cohorts when young. Inglehart’s theory (see above) does not answer this question because it does not address the mechanical impediment of previously inherited partisanship. The decline of cleavage politics (Franklin 2009) was about breaking a link between party choice and “inherited” social characteristics (mainly class and religion) that new voters shared with their parents.9 The broken link showed itself partly in younger voters supporting a party other than the one associated with their social group and partly in their support for new parties not clearly associated with any social groups. Evidently this presumably tentative association between young voters and parties comes with the possibility that these young voters will not only support a party different from the one their parents supported but will also switch between parties, “trying out” one party after another until they settle on a party that they continue to support. Gomez (2013) documents the far higher volatility among younger than among older voters, which is evidently a concomitant of lack of partisanship. With the lower power of social cleavages to determine party choice the link to parental partisanship is also broken,10 though over time any new basis for party choice may acquire intergenerational continuity and hence lower levels of volatility.

Figure 34.4 Proportion of US strong partisans by electoral cohort, 1952–2012

Source: American National Election Studies, 1952–2012, cumulative file. Shaded areas are 95 percent confidence intervals.

It should be possible to determine whether this volatility is cause or consequence of low partisanship (and whether the direction of causality is the same in Europe as in the US) but this topic is far beyond the remit of a handbook chapter (see Bowler, this volume, for more). We note, however, that if volatility is indeed the cause then, in the absence of renewed major volatility, overall partisanship should recover over time (as it has in recent years in the US). Of course major volatility can always return, as it has in the 2010s in many European countries, and the volatility approach to understanding the evolving cohort differences in levels of partisanship would lead us to expect a renewed drop in partisanship as a consequence.

Confirmation that partisanship is enhanced by behavioral consistency in party choice (Dinas, in this volume) explains the clear existence of a life-cycle effect among those reaching voting age in the contemporary period. The formation of party attachments has thus come to be a self-reinforcing mechanism, just like the mechanism we observed for turnout. At all events, it is clear that the oldest generations are least likely to change their longstanding party preferences and that any patterns of long-term change in party support are most likely to be observed among the youngest cohorts. This observation has strong implications for realignment processes.

Realignments of party systems

The word “realignment” describes large and longstanding changes in the character of a party system, often a change in the identity of the party holding a dominant position and usually of the policies implemented by the resulting government. How realignments come about has been a major concern in political science research for many years, but the sea change we described earlier introduced a discontinuity in the nature of such realignments. In the days of frozen party systems, realignments were cataclysmic events, but this is evidently not so true of the modern era. Today, realignments are more generally incremental than cataclysmic.

Given that people as they age get set in their ways, so that they develop certain behavioral regularities in terms of turnout and party support, we would assume that the set of considerations underlying party choice would also become stable over time. So someone who, based on religious values and beliefs, acquired a preference for a Christian Democratic Party during her most formative years will be unlikely to change this way of looking at the party system when she is 80 years old. Yet, a new voter, who is still learning her way around the party system and the main differences among the parties, is more likely to base her choice on issues that are currently most salient (see Knutsen in this volume). So realignments should have a strong generational component. Our literature search found this to be a very under-studied topic.

The massive European literature on realignment has focused traditionally on the decline of religious and class voting; a process that is visible across Western Europe in the last quarter of the twentieth century, but which began at different times in different countries (see, for example, Franklin 2009) and the few studies that looked at cohort differences in the factors determining the vote have confirmed that “cleavage voting,” in terms of social class or religion, is most prominent among the oldest cohorts, which entered their electorates before the 1970s (see, for example, Franklin 2009; van der Brug 2010). But these studies do not include the most recent cohorts.

Evidently, in the contemporary era following the decline of cleavage politics, the engine of generational replacement can readily account for long-term change in party systems. The unfreezing of party systems opened up opportunities for new parties to compete for political support – especially green parties and far-right parties (Franklin and Rüdig 1995; van der Brug and van Spanje 2009). To the extent that young voters adopted habits of voting for such new parties, those parties will have tended to gain support over time as young voters aged and became “set” in their support for the parties concerned. To the extent that previously dominant parties failed to replace their supporters because of this movement toward new parties, established parties will in the same way have lost support. Such changes, once they engage the motor of generational replacement, become both progressive and enduring.

In the United States, Carmines and Stimson (1981, 1986, 1989) showed that electorates contain quite enough younger voters, lacking enduring party attachments, to account for relatively rapid change. They describe long-term change in party support in a manner that follows closely the logic set out above for long-term change in turnout, though it employs a different vocabulary. The “reform election” of turnout theory becomes a “critical moment” in issue evolution. Most such moments concern temporary defections of partisans who later return to their long-term party orientations. A few such moments, however, have more permanent effects “driven by normal population replacement” (1986: 902). The picture drawn for turnout in Figures 34.1 and 34.2 above is echoed in Meffert, Norpoth and Ruhil (2001), who explicitly build on Carmines and Stimson’s logic and whose Figure 2 (Meffert, Norpoth and Ruhil 2001: 959) shows the same sharp drop followed by long-term reinforcement as shown in our Figures 34.1 and 34.2. However, Meffert, Norpoth and Ruhil make no direct reference to generational replacement as an engine of change, and we found this to be typical. Osborne, Sears and Valentino (2011) show that the oldest cohorts in the South were most resistant to the region-wide realignment of support from Democrats to Republicans, while at the same time they were most conservative in terms of their value orientations; but the generational implications are not addressed (see also Miller 1991; Abramowitz and Saunders 1998; Valentino and Sears 2005; Lewis-Beck et al. 2008). The arguments of Carmines and Stimson appear never to have been called into question but, though they are often referenced, neither are they used as building blocks for developing models of change based on generational replacement.

Few scholars, either in the US or elsewhere, recognize realignment processes as currently understood to differ in any important way from the processes that existed in the era of frozen cleavages, though Carmines and Stimson (1986: 902) observe that “[T]he critical moment is … large enough to be noticeable, but considerably less dramatic than the critical election of traditional realignment theory.” They do not address the question why this is so, but our earlier distinction between traditional partisan inheritance and contemporary partisan learning makes it clear that before the 1960s the US political world was distinctively different, just as was the European political world before the 1980s. And the classic first attempt at making sense of longterm change in US politics, found in Campbell et al. (1960), was written about that earlier world. In addressing the American “New Deal” realignment of the 1930s, these authors focus on new voters as engines of change and stress that it likely took more than one election to accomplish the realignment (Campbell et al. 1990: 525). Twenty years later, Andersen (1979a, 1979b) re-analyzed The American Voter data employed by Campbell et al. in order to reconstruct the 1930s electorate on the basis of recall of first vote. She showed how the huge increase in the size of the 1930s electorate due to late nineteenth century immigration could have supplied the votes needed to fuel the New Deal realignment without the need for massive conversion of existing voters.11

In Europe, the importance of new voters has been underlined by the evident role of successive enlargements of European electorates that happened with successive franchise extensions occurring in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and repeatedly led to new party formation; and Franklin and Ladner (1995) demonstrated how the British realigning election of 1945, which saw the achievement of majority status by the British Labour Party, was fueled almost exclusively by generational replacement, using the same methodology as Andersen’s (1979) reconstruction. Because there was no election in Britain between 1935 and 1945, the distinction between a realigning election and a realigning era is not relevant in the British case, which thus produces findings that can less readily be contested than the corresponding US findings (see note 11).

Carmines and Stimson (1981) repeatedly stress that generational replacement is a constant fact of life but does not become an engine of change in party support unless fueled by an important (generally emotionally charged) issue (see, for example, Carmines and Stimson 1981: 109). In the US, such issues have focused primarily on race, abortion and the role of the government in the economy. In Europe, they have also focused on the role of government and, more recently, on environmental and immigration concerns. When citizens base their party choice on different considerations than before, the relationships between parties and voters change, new conflict lines structure party competition, which in turn change the opportunities for the formation of governing coalitions in continental European countries and for a switch between dominant parties in the US and UK. Stimson and Carmines, along with other scholars studying change in US party systems, stress the role of party elites in fueling issue change, with voters falling into line behind new party positions. In Europe, we have seen such developments as well (Mrs. Thatcher’s conservative revolution in Britain had widespread repercussions across other European countries). However, in Europe new parties are often the agents pushing new issues onto the political agenda, and thus driving realignment.

In sum, realignments of party systems occur mainly due to supply-side changes in what policies are on offer rather than to citizens changing their bases of party support (such changes may also be involved in the decline of cleavage politics described earlier, as proposed in Evans and Northmore-Ball, this volume); though the role of changing voter norms and concerns in providing opportunities for entrepreneurial initiatives should not be ignored (cf. Dalton 2015). At least some issues (those often seen as being part of the “socio-cultural dimension” such as immigration and European integration) are more important to young voters than to voters of earlier generations (Walczak, van der Brug and de Vries 2012), a finding confirmed by Wagner and Kritzinger (2012).

The role of left–right self-placement in relation to the left–right locations of parties is crucial in Europe, but research on generational differences in the effect of left–right location on the vote is scarce. Van der Brug (2010) found that left–right distances exert the strongest effect on party preferences for the generation socialized in the 1970s/1980s. A complicating factor is that new issues become part of the left–right dimension when these become politicized (see, for example, Kitschelt 2004; van der Brug and van Spanje 2009). Consequently, the meaning of the terms left and right change gradually over time. De Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee (2013) demonstrated that, since the 1990s, left–right positions of Dutch voters have become gradually more correlated with attitudes toward immigration. Rekker (2016) showed that there is a clear generational pattern underneath this. In the older cohorts, secular-religious issues are most strongly correlated with left–right. In the middle-aged cohorts, a relatively strong correlation is found between left–right and civil liberties, while in the youngest cohorts, the correlation with attitudes toward immigration is relatively strong. It thus seems that new voters learn to orient themselves toward the party system through the lens of left–right locations. Yet, the issues that they associate with left and right are particularly the issues that are most salient to voters during their “formative years.” It is likely that the same process occurs in the US in regard to the liberal–conservative dimension there, as suggested by Carmines and Stimson (1986). However, the evidence for this account of electoral realignments is still sketchy.

Conclusions and new avenues

In order to understand electoral change, or social change more generally, we need to be aware of the fact that the youngest cohorts of voters are the most likely to be affected by new developments and events, while the oldest cohorts are most resistant to change. Even though most electoral scholars are aware of this, there is no widely accepted methodology for incorporating processes of generational replacement into accounts of realignment processes.

Our contribution has focused on cohort differences in relation to three topics in electoral research: turnout, partisanship and the determinants of party support. As far as we can see, two areas require more research. The first is the matter of generational differences in the causal relationship between partisanship and party choice. Since the publication of the American Voter (Campbell et al. 1960), electoral researchers have assumed partisanship to be a stable political orientation that is acquired early in life and that structures party choice thereafter. However, the descriptive patterns that we have shown seem to clearly indicate that partisanship in the contemporary era only develops somewhat later, opening an opportunity for new behavioral norms such as those highlighted by Dalton (2015).

A second topic that requires (further) research is the extent to which different generations base their party choice on different sets of considerations. Evidence from Europe suggests that socio-cultural issues are more important determinants of the vote for younger than for older cohorts. Also, left–right orientations are more strongly correlated with socio-cultural issues among younger than older citizens. While this suggests that realignment involves not the arrival of a different dimension than left–right but rather the evolution of left–right itself as it acquires a new meaning, the evidence is a bit thin. In the US, there has been more work on the role of specific issues, but the role of generational replacement in bringing new issues to bear on party choice, though repeatedly affirmed, has been studied no more extensively than in Europe.

Notes

1These are often known as “impressionable years.”

2Attempts to do so carry various risks that make it hard to unambiguously attribute effects to each component of the APC (age–period–cohort) framework. See contributions of Neundorf and Niemi (2014) for discussion.

3Thus a panel study with waves fielded annually from 1970 to 1990 would contain no-one in the 1990 wave who reached voting age before 1970 (so no-one under 38 years old in 1990, 37 years old in 1989, and so on) and no-one who died before 1990 (so almost no-one over the age of 60 in 1970, 61 in 1971, and so on).

4Developmental psychologists argue that basic orientations are already formed during (pre-) adolescent years (see, for example, Sapiro 2004; Campbell 2008; Hooghe 2004; Hooghe and Wilkenfeld 2008; Torney-Purta, Barber and Richardson 2004). However, for research on electoral processes, understanding the exact origins of such attitudes seems less urgent, which is why we do not dwell on this line of research.

5A sea-change of this kind invalidates the expectations expressed by, for example, Wattenberg (2015) that behavioral patterns should be found to be the same in different eras, an important test for his contrary thesis.

6The fact that party systems started to unfreeze a decade earlier than the decline of partisanship suggests that, if the connection was causal, cleavage decline caused lower partisanship (perhaps by way of increased volatility), but this must be the subject of future research.

7When we break out the data for Britain, we see a renewed decline in partisanship in the youngest cohorts starting in the mid-1990s, perhaps a precursor of effects that will be seen in other countries as the volatility that accompanies anti-EU attitudes spreads across Europe, especially in the aftermath of the Great Recession. See below for more discussion on this point.

8Van der Eijk and Franklin (2009), who show cohorts delineated by first election rather than by birth decade, also show such a fall and recovery for US cohorts born between 1935 and 1947 and entering the US electorate between 1956 and 1968 (Figure 7.1, page 181).

9This approach does not fully answer the question either, though see van der Eijk et al. (2009) for a discussion of this point. But it gets closer to the mechanics involved, raising the question (discussed more fully below) whether post-material (or any other) values result from new party preferences rather than causing them.

10Much controversy surrounds the question of whether and to what extent links between parties and social groups declined in the last third of the twentieth century (see Evans and Northmore-Ball in this volume). By focusing on the unfreezing of party systems rather than on the extent of class and religious voting we hope to bypass that controversy.

11Andersen’s conclusions were contested in a widely cited re-analysis of 1930s survey data (Erikson and Tedin 1981) but those data did not come from a random sample, and the conversions observed in those data may not have been enduring and may not have fueled the realignment. A still later reconstruction, based on the same and other 1930s data weighted to correct for sampling bias (Campbell 1985), reaffirmed Andersen’s findings based on 1950s recall data. However, US literature to this day (see, for example, Meffert, Norpoth and Ruhil 2001; Carmines and Wagner 2006; Campbell and Trilling 2014) tends to avoid addressing the role of newly eligible voters in fueling the evolution of party preferences, as already stated. However, these works often mention in passing the role of younger voters in being especially susceptible to new influences.

References

Abramowitz, A. I. and Saunders, K. L. (1998) “Ideological Realignment in the U.S. Electorate,” Journal of Politics, vol. 60, no. 3, August, 634–652.

Alford, R. (1963) Party and Society: The Anglo-American Democracies, Chicago: Rand McNally.

Andersen, K. (1979a) “Generation, Partisan Shift, and Realignment: A Glance Back to the New Deal,” in Nie, N. H., Verba, S. and Petrocik, J. R. (eds.) The Changing American Voter, 2nd Edition, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: 74–95.

Andersen, K. (1979b) The Creation of a Democratic Majority, 1928–1936, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bølstad, J., Dinas, E. and Riera, P. (2013) “Tactical Voting and Party Preferences: A Test of Cognitive Dissonance Theory,” Political Behavior, vol. 35, no. 3, September, 429–452.

Brug, W. van der (2010) “Structural and Ideological Voting in Age Cohorts,” West European Politics, vol. 33, no. 3, May, 586–607.

Brug, W. van der and Spanje, J. van (2009) “Immigration, Europe and the ‘New’ Cultural Dimension,” European Journal of Political Research, vol. 48, no. 3, May, 309–334.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E. and Stokes, D. E. (1960) The American Voter, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Campbell, B. A. and Trilling, R. J. (2014) Realignment in American Politics: Toward a Theory, Austin: University of Texas Press.

Campbell, D. E. (2008) “Voice in the Classroom: How an Open Classroom Climate Fosters Political Engagement Among Adolescents,” Political Behavior, vol. 30, no. 4, December, 437–454.

Campbell, J. E. (1985) “Sources of the New Deal Realignment: The Contributions of Conversion and Mobilization to Partisan Change,” The Western Political Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 3, September, 357–376.

Carmines, E. G. and Stimson, J. A. (1981) “Issue Evolution, Population Replacement, and Normal Partisan Change,” American Political Science Review, vol. 75, no. 1, March, 107–118.

Carmines, E. G. and Stimson, J. A. (1986) “On the Structure and Sequence of Issue Evolution,” American Political Science Review, vol. 80, no. 3, September, 901–920.

Carmines, E. G. and Stimson, J. A. (1989) Issue Evolution: Race and the Transformation of American Politics, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Carmines, E. G. and Wagner, M. W. (2006) “Political Issues and Party Alignments: Assessing the Issue Evolution Perspective,” Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 9, June, 67–81.

Dalton, R. J. (2015) The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation is Reshaping American Politics, Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Dinas, E. (2014) “Does Choice Bring Loyalty? Electoral Participation and the Development of Party Identification,” American Journal of Political Science, vol. 58, no. 2, April, 449–465.

Eijk, C. van der and Franklin, M. (2009) Elections and Voters, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Eijk, C., van der, Franklin, M., Mackie, T. and Valen, H. (2009) “Cleavages, Conflict Resolution and Democracy,” in Franklin, M., Mackie, T. and Valen, H. (eds.) Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 403–426.

Erikson, R. S. and Tedin, K. L. (1981) “The 1928–1936 Partisan Realignment: The Case for the Conversion Hypothesis,” American Political Science Review, vol. 75, no. 4, December, 951–962.

Franklin, M. (2004) Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies Since 1945, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Franklin, M. (2009) “The Decline of Cleavage Politics,” in Franklin, M., Mackie, T. and Valen, H. (eds.) Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 381–402.

Franklin, M. and Ladner, M. (1995) “The Undoing of Winston Churchill: Mobilization and Conversion in the 1945 Realignment of British Voters,” British Journal of Political Science, vol. 25, no. 4, October, 429–452.

Franklin, M. and Rüdig, W. (1995) “On the Durability of Green Politics: Evidence from the 1989 European Election Study,” Comparative Political Studies, vol. 28, no. 3, October, 409–439.

Franklin, M., Mackie, T. and Valen, H. (eds.) (2009) Electoral Change: Responses to Evolving Social and Attitudinal Structures in Western Countries, 2nd Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gomez, R. (2013) “All That You Can (Not) Leave Behind: Habituation and Vote Loyalty in the Netherlands,” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, vol. 23, no. 2, 134–153.

Heath, O. (2007) “Explaining Turnout Decline in Britain, 1964–2005: Party Identification and the Political Context,” Political Behavior, vol. 29, no. 4, December, 493–516.

Holmberg, S. (2007) “Partisanship Reconsidered,” in Dalton, R. J. and Klingemann, H-D. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, Oxford: Oxford University Press: 557–570.

Hooghe, M. (2004) “Political Socialization and the Future of Politics,” Acta Politica, vol. 39, no. 4, December, 331–341.

Hooghe, M. and Wilkenfeld, B. (2008) “The Stability of Political Attitudes and Behaviors across Adolescence and Early Adulthood: A Comparison of Survey Data on Adolescents and Young Adults in Eight Countries,” Journal of Youth Adolescence, vol. 37, no. 2, February, 155–167.

Inglehart, R. (1984) “The Changing Structure of Political Cleavages in Western Society,” in Dalton, R. J., Flanagan, S. C. and Beck, P. A. (eds.) Electoral Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Realignment or Dealignment? Princeton: Princeton University Press: 25–69.

Jennings, M. K. (2007) “Political Socialization,” in Dalton, R. J. and Klingemann, H. D. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, Oxford: Oxford University Press: 29–44.

Jennings, M. K. and Markus, G. B. (1984) “Partisan Orientations Over the Long Haul: Results from the Three-Wave Political Socialization Panel Study,” American Political Science Review, vol. 78, no. 4, December, 1000–1018.

Jennings, M. K. and Niemi, R. G. (1968) “The Transmission of Political Values from Parent to Child,” American Political Science Review, vol. 62, no. 1, March, 169–184.

Kitschelt, H. (2004) Diversification and Reconfiguration of Party Systems in Postindustrial Democracies, Bonn: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Lewis-Beck, M. S., Jacoby, W. G., Norpoth, H. and Weisberg, H. F. (2008) The American Voter Revisited, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Lipset, S. M. and Rokkan, S. (1967) (eds.) Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives, Volume 7, New York: Free Press.

Meffert, M. F., Norpoth, H. and Ruhil, A. V. (2001) “Realignment and Macropartisanship,” American Political Science Review, vol. 95, no. 4, December, 953–962.

Miller, W. E. (1991) “Party Identification, Realignment, and Party Voting: Back to the Basics,” The American Political Science Review, vol. 85, no. 2, June, 557–568.

Neundorf, A. and Niemi, R. G. (2014) “Beyond Political Socialization: New Approaches to Age, Period, Cohort Analysis,” Electoral Studies, vol. 33, March, 1–6.

Nie, N. H., Verba, S. and Petrocik, J. R. (1979), The Changing American Voter, 2nd Edition, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Osborne, D., Sears, D. O. and Valentino, N. A. (2011) “The End of the Solidly Democratic South: The Impressionable Years Hypothesis,” Political Psychology, vol. 32, no. 1, February, 81–108.

Rekker, R. (2016) “The Lasting Impact of Adolescence on Left-Right Identification: Cohort Replacement and Intracohort Change in Associations with Issue Attitudes,” Electoral Studies, vol. 44, December, 120–131.

Sapiro, V. (2004), “Not Your Parents’ Political Socialization: Introduction for a New Generation,” Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 7, June, 1–23.

Scervini, F. and Segatti, P. (2012) “Education, Inequality and Electoral Participation,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, vol. 30, no. 4, December, 403–413.

Thomassen, J. (1976) “Party Identification as a Cross-National Concept: Its Meaning in the Netherlands,” in Budge, I., Crewe, I. and Farlie, D. (eds.) Party Identification and Beyond: Representations of Voting and Party Competition, London: John Wiley: 263–266.

Torney-Purta, J., Barber, C. H. and Richardson, W. K. (2004) “Trust in Government-Related Institutions and Political Engagement Among Adolescents in Six Countries,” Acta Politica, vol. 39, no. 4, December, 380–406.

Valentino, N. A. and Sears, D. O. (2005) “Old Times There are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South,” American Journal of Political Science, vol. 49, no. 3, July, 672–688.

Vries, C.E. de Hakhverdian, A. and Lancee, B. (2013) “The Dynamics of Voters’ Left/Right Identification: The Role of Economic and Cultural Attitudes,” Political Science Research and Methods, vol. 1, no. 2, December, 223–238.

Wagner, M. and S. Kritzinger (2012) “Ideological Dimensions and Vote Choice: Age Group Differences in Austria,” Electoral Studies, vol. 31, no. 2, June, 285–296.

Walczak, A., van der Brug, W. and de Vries, C. (2012) “Long- and Short-Term Determinants of Party Preferences: Inter-Generational Differences in Western and East Central Europe,” Electoral Studies, vol. 31, no. 2, June, 273–284.

Wattenberg, M. P. (2015) Is Voting for Young People?, New York: Routledge.