In high school my friend Dylan said something to me that changed my life. We’d gone to a smoothie place on our lunch break, and when I attempted to order a medium smoothie, Dylan said, “Just get a large. It’s only a dollar more. If you’re gonna spend four dollars on a smoothie, you might as well spend five and get a large.” When Dylan said that, I felt like I’d been blessed with wise counsel from Confucius himself. His words rang so true to me. Since I was already spending too much money on pulverized fruit, why not go for broke? For the rest of the afternoon during calculus I suckled contently at my oversize peach smoothie, peaceful and serene, oblivious to the world’s problems. I believe I came away with something greater than tiresome math facts that day, and that was a newly adopted adage for life. That simple concept of indulgence would stick with me, and I would go on to apply it to every aspect of my adult life. Whenever possible, I upgrade. I treat myself. I find a way to convince myself that I deserve it, even when I don’t. As a result, I always live beyond my means.

In Boston, it was easy to live large. Housing and food were paid for, so I was able to spend my funds on whatever I wanted. Eight-disc-at-a-time Netflix membership? Why not? Top-shelf vodka every Saturday night? Certainly! When I moved to Portland I figured I’d be able to keep up my extravagant ways. I assumed I’d immediately land a killer job as something vague and creative, like “image consultant” or “emotional architect,” unaware that Portland was already bursting at the seams with unemployed, entitled youths. I believed I’d send out a few cleverly designed resumes, be hired immediately, and proceed to live a baller lifestyle, like a skinny, white Soulja Boy.

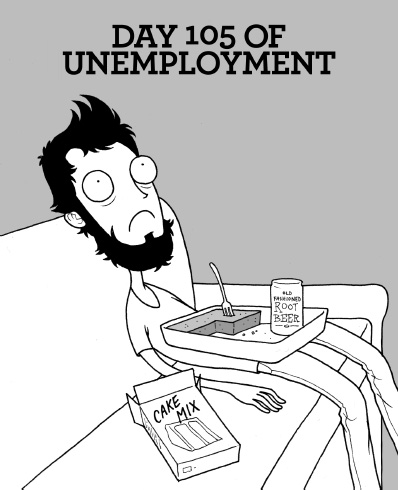

Such was not the case. At first, I applied for jobs with an unwavering can-do attitude, tailoring resumes for job specificity and carefully crafting cover letters to email prospective employers. Sadly, it soon became clear that I was essentially sending resumes into the void. Not one of my applications was replied to. Somewhere around month four of my job search, I began to suspect that my expectations had been flawed, and I started to worry. Why wasn’t my phone abuzz with messages from employers looking to hire a fine arts graduate with no adult work experience? In twelve weeks I’d only received one callback, and it turned out to be a mix-up. They’d meant to call a German girl named Ada Ellis. Disheartened, I sank into a mild depression.

My joblessness wasn’t for a lack of trying. In addition to the countless resumes I emailed, I estimate I printed a metric ton of hardcopy resumes and hoofed them around town to anyone who I thought might take one. I gave up the notion of job-related pride. I begged restaurants and coffee shops to keep one on file, even though they weren’t hiring. I handed out copies to video store managers six years younger than me. I wouldn’t be surprised if my job hunt alone caused the annihilation of every forest in the Pacific Northwest.

Weeks passed and my checking account declined steadily. I put my student loans on hold. I sold my car because I couldn’t keep up with the payments. I started using coupons at the grocery store, donning huge sunglasses and a fake mustache so nobody would recognize me. Every night on my way home from an unsuccessful job search, I’d pass the Taco Bell on my block, more and more aware that my future might involve a career in fast food.

My mom would call me on the phone and ask how I was doing, and I’d always tell her “fine,” though I was anything but. At night I’d lie awake, terrified of what would happen if I couldn’t find a job and all my money ran out. I had no other option, no fallback plan. Moving home to Montana wasn’t an alternative I was willing to consider. I’d rather sleep on the streets and eat garbage. I’d made the decision to move to Portland and I had to make it work. It just had to work. I had too much pride to admit failure and move home, and even then I don’t think my mother would have allowed it. I felt a similar disillusionment with adulthood to the one I’d felt after my years in art school. I bet that Zoe chick is making millions off her condom-covered Virgin Mary figurines, I thought. But I couldn’t give up. There was no alternative battle plan. There was no tactical withdrawal.

When I finally landed an interview at a bookstore, it only proved I had more to worry about than simply getting callbacks from employers. Apparently my interview skills had atrophied and died. I arrived to the interview on time wearing my most professional outfit. But I was so nervous that when the interviewer asked what the last great book I read was, I froze up. Suddenly I couldn’t remember a single book I’d ever read. I sputtered a nonsense answer about “reading so much it’s hard to decide,” and then stared at the interviewer awkwardly until he moved onto the next question. The saddest part is that I really do read constantly. I could’ve talked about being swept up in the haunting tragedy of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, or how Kavalier & Clay was so achingly beautiful I didn’t know what to do with myself after finishing it—as if nothing else really seemed important anymore—but instead I gave some Palin-esque response about liking everything. I might as well have responded with, “What’s a book?” and flicked a booger at the interviewer’s face. Needless to say, I didn’t land that job.

I was down to ninety-seven dollars in my checking account when I finally found work, and ironically it wasn’t a job I’d even applied for. It was an overcast Tuesday afternoon when my phone rang with a number I didn’t recognize. A woman named Patricia introduced herself and asked me if I’d be interested in a paid internship at her interior design and staging company. She told me that she’d stumbled upon my website and figured I might be a good fit.

“I need someone to design promotional materials and stuff,” she explained casually. “Brochures and the like. Maybe someone to do social media crap. Can you use Twitter? I’m terrible with the computer.”

I wondered if she could hear through the phone the giant tears of relief splashing onto my unwashed hoodie.

The next day I met Patricia for an interview. She was a well-dressed woman of about forty, prim and poised, though to call her attire dated would be putting it softly. She looked like she should be bossing around copywriters at a 1980s fashion magazine with a name like Belles Ordures or Quite! Her hair was large and unmoving, probably hair-sprayed within inches of its life. She wore a mauve pantsuit with shoulder pads and gaudy gold jewelry. Scanning the resume I’d brought, she asked which computer programs I was familiar with and if I could use Adobe InDesign. I lied and said yes, figuring I could learn it later if I needed to. She set my resume aside and gave me a brief rundown of what I could expect from the job. Then she sipped on her latte for twenty minutes and talked about her cat, Evita. I listened contently, happy to even be considered for what was in all honesty a lifesaving opportunity. I had no idea what made me stand out in her mind, but by the time her coffee was empty, she’d offered me the position. I couldn’t help but be thrilled. She told me her business was small and that I’d be doing mostly menial tasks, but I didn’t mind. I’d be working in my field, more or less.

Patricia ran her business out of her home, and I started work the next week. My first morning, Patricia sat me down to discuss my salary. It wasn’t much, but it was enough for me to live on for a while. In the months that followed I figured out that Patricia was completely forgetful and disorganized as a rule. Oftentimes I’d benefit from her absentmindedness, but just as frequently it created problems, and I quickly became the company’s Swiss Army Knife, solving dilemmas left and right. One day I’d spend three hours on the phone with the printers over a mix-up with a typo on a flyer, and the next I’d have to sync Patricia’s email on her cell because she’d somehow reset the device back to factory specs for the fifth time. Besides Patricia, there were only a couple of other people at the company, and they mostly dealt with deliveries, so the bulk of the problems fell to me. I made sure never to complain about the mountain of odd jobs dumped on my lap, as I still felt the position was a godsend. For the most part I stayed on top of things, but Patricia was constantly flustered, all the time. I’d walk into her office with some paperwork or a design issue, and she’d almost always be screaming at someone on the phone. She never sounded angry, just batty and stressed, like a tornado of polyester blazers and tarnished costume jewelry. Still, I found her amusing and was happy to help her. For all her yelling, she never screamed at me, and the fact that she’d employed me at such a difficult time endeared her to me, nutty as she was.

Although Patricia had been in business for a decade, I frequently wondered how the company stayed afloat. She seemed to be eternally out of touch. I once accepted a delivery for fifteen rolls of sea-foam-colored wallpaper accented with big pink flowers. It was hideous, and I couldn’t imagine anyone using it. Patricia told me she was staging a beach house in Depoe Bay, and I thought, Is it a beach house for Scott Baio? Are you traveling back in time to 1986? I figured her aesthetic catered to a specific clientele, so I kept my mouth shut. In the end the wallpaper must have been rejected by whichever client it was intended for because it sat slumped in the corner of Patricia’s office for the rest of my time there.

Patricia seemed to be trapped in a bit of a time warp herself. I wondered how she kept her hair so eternally motionless and if she had to get blazers with shoulder pads specially made. I pictured her hunched in front of Designing Women reruns, brow furrowed, jotting down fashion tips onto a ledger. Whatever the case may have been, Patricia’s idiosyncrasies seemed to work for her so I went about my business and she went about hers. Eventually we fell into a routine where I could come into work and field various problems on my own. Some days Patricia and I never even crossed paths. When we did it was usually because Patricia had a task for me to do that she considered urgent but that didn’t make much sense.

I’d been working for Patricia for about three months when I came into her office one morning and found that she had turned off all the lights in the room and was peering out the window cautiously. As I ventured toward her, she flapped her hand at me and made a shushing noise. “Uh, why’s it so dark in here, Patty?” I asked.

Without turning toward me, she said, “I may or may not have a home business license. The homeowners association is trying to oust me.” I stood in the doorway for a moment longer, then gingerly set some forms on Patricia’s desk.

“Okay, well, I’m going to go work on the Rosier account,” I said and turned to leave.

“Wait!” Patricia whispered, smoothing one side of her concrete hairdo. “If anyone comes up to you outside and tries to talk to you, just say you’re visiting a family member. No! Say you don’t speak English. Can you speak German? Aren’t you German?”

“Um, I think my great-grandmother was?” I replied. “I mean, I don’t speak German…” I started inching toward the door slowly. “I’m gonna get to work…” Patricia didn’t turn around.

As the months rolled on, Patricia’s expectations of me seemed to change. She became less and less concerned with the quality of my work and instead seemed to view me as a friend she paid to hang around her house. She’d routinely call me into her office to discuss what had happened on Desperate Housewives the night before, seemingly unconcerned that I had no idea who the Housewives were or why they were so Desperate. When she started demanding I take care of her cat while she made phone calls, I began to question my future at the company.

It dawned on me that working in someone else’s home office might be a slippery slope. I pictured myself years down the road, sitting on the couch next to Patricia, both of us in matching terry-cloth robes, our hair in similar pink curlers, with Evita stretching out on the cushions between us. Despite this alarming prospect, I stayed on.

One afternoon a few weeks later, there was a knock at the front door. We weren’t expecting any deliveries that day, so I was immediately cautious, expecting to see the homeowners association with torches and pitchforks. I opened the door with trepidation and was instead bombarded by a couple of chipper, rosy-cheeked missionaries. Dressed in identical black slacks and crisp, pressed white shirts, they greeted me with such cloying earnestness I almost felt assaulted.

The missionaries began their standard speech, asking kindly if they could tell me about The Jesus. Though it would’ve been perfectly acceptable for me to decline, I told them I’d be happy to listen. For the most part, I find it impossible to say no, usually out of fear of offending someone. In college, while roaming a satellite building looking for a seminar on printmaking, I accidentally stumbled upon an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and unknowingly joined it, and didn’t leave until the session was over. I was afraid if I got up and left, someone would call me out on it, so I stayed and listened for the entire hour, occasionally nodding to let them know that yes, I got it.

While I half listened to the missionaries inform me about angels and stuff, Patricia appeared behind me in the hallway. Seeing that I was in need of saving, she devised what I’m sure she thought was a clever way of getting rid of the visitors.

The missionaries had seemed very pleased at being heard, so when I saw their expressions falter at Patricia’s words, I felt a mild pang of guilt. The missionary who’d been speaking trailed off midsentence, his eyes shifting to the grinning woman behind me. His smile remained steadfast, if a little more strained than before. A few moments of silence passed, and then the other one said, “Have a blessed day,” and as quickly as they had appeared they were gone. Behind me, Patricia chuckled. I knew she was joking, but I’d already become a willing ear for television gossip and the caretaker of her cat. I wondered if it was such a leap to suspect one day she might walk into my work space wearing nothing but oversize brass earrings and gold pumps. I tried to push it out of my mind, but at that moment I began to wonder about other job opportunities.

Four or five weeks after the missionary incident, I learned through a series of misguided emails that Patricia was being sued by two clients, and was in trouble with the government for withholding taxes. Before realizing I wasn’t meant to be on that particular email thread, I’d gleaned that Patricia was clearly at fault regarding at least one of the lawsuits, and that she was in hot water with the tax issue.

She was a total flake of a boss, and she’d possibly sexually harassed me on a couple of occasions—albeit a gentle sort of harassment (I’m sure it would never have reached Nine to Five levels of inappropriateness)—but still, I liked Patricia, and was grateful that she had rescued me from unemployment. It pained me to know that I’d have to start formulating my departure. The troubles at the company were nothing I could help with, and probably nothing Patricia herself could circumvent in the long run. I knew I had to get off the ship before it went down. I couldn’t ride that one out. I had to bounce.

When I crept into Patricia’s office a few days later with a quitting speech memorized in my head, I expected her to be angry or hurt. I told her I’d need to put in my two weeks’ notice, telling her that my time had come to “explore alternate paths in my career,” whatever that meant. I figured it was best to keep things vague and polite. Patricia appeared to understand what I was getting at.

“You’ve been a huge help,” she said sweetly. “I’ll miss you, and if you ever need anything, let me know.” Her response surprised me. I suppose people quit jobs all the time under perfectly friendly circumstances, but this was my first experience in voluntary termination. Every time somebody quits a job in the movies, there’s yelling and fighting and possibly a gun involved. I didn’t know how this sort of thing went down in real life. My only other real job was in high school working the phones for a company that installed and maintained pools. I was supposed to field simple questions like, “How much chlorine do I add to my pool?” I regularly screwed up my math while answering questions and might’ve caused a few schoolchildren to get chlorine poisoning. I was fired from that job after a couple of months.

My final weeks passed by quickly. I cataloged and filed with all my heart, trying to prepare Patricia as best I could for my exit.

One day during my last week I came into work to find the house oddly quiet. Patricia, who would normally be jabbering on her phone already, was silent, and the living room TV, usually fixed on the Today show, was cold and dark. It felt sort of lonely, but I shrugged it off and unpacked my laptop and got to work on the last bit of lingering paperwork I had left.

I heard Patricia come up the stairs around ten. She bypassed the room I was working in and walked down the hall to the bathroom, where I heard the shower turn on. Something wasn’t right. The water ran for about fifteen minutes, then stopped, and a few minutes later I heard a blow dryer. Finally I heard Patricia emerge and make her way back down the hall. This time, she noticed me working in the spare room. She gaped at me, hair blown out and messy, a toothbrush dangling from her mouth.

“It’s Saturday,” she told me plainly. “Do you not know your days of the week, Adam? I wish you’d told me sooner, there are a ton of tax credits for hiring people with special needs.”

“I guess I got mixed up,” I said, embarrassed. I usually calculate what day it is by referencing whatever TV show was on the night before, but somehow the days had started blurring together for me.

“I’ll clear out,” I said and began stuffing papers into my backpack.

“Well, you’re already here,” Patricia said. She paused for a second and returned to the bathroom to spit out her toothpaste and gargle some mouthwash before returning and continuing her thought. “I just bought a Wii and I can’t figure it out. Wanna set it up for me? I’ll pay you for the time you’re here.”

I zipped up my backpack. “Yeah, that won’t take long. Welcome to this century, by the way.”

She smiled. I removed the Wii from the box and had it hooked up to the television in a matter of minutes. I directed her through the on-screen menus and loaded up a game for us to play. She learned the mechanics of it quickly and promptly kicked my butt. Granted, I was impaired by Evita trying to chomp my ankles. I would have called interference, but after a year of creating spreadsheets that amounted to nothing, color-correcting nonsensical brochures, and endlessly filing things I knew would never be retrieved, it felt good to be accomplishing something worthwhile, even if it was just as simple as helping Patricia indulge herself in Wii Boxing.