‘What a waste,’ sighed Olive. She hosed the last of the chocolate off her shoes and watched it soak into the grass.

Shaggy the mutt licked the tap.

Olive looked up at the moonlit sky and whispered, ‘Disaster.’ But this time she was not talking about the chocolate. Although, obviously, any time chocolate is thrown in a bin, forgotten at the back of a pantry or hosed into the grass could quite reasonably be called a disaster.

No. Olive was talking about her dear departed friends. Those who had borne the brunt of Thistlebloom’s wrath.

One chocolate-coated student looks much the same as another, so Thistlebloom had simply expelled those she could identify by shape and size. Innocence or guilt had little to do with it, and the talking animals faired rather poorly. Blimp, Helga the hippo, Steve and George the hermit crabs, Flick the goanna, Elizabeth-Jane the giraffe, Valerie the owl and Reuben the rabbit were all sent on their way. Likewise, Anastasia and Alfonzo had been easy to single out, as they had been swinging from a chandelier at the time. They had thought they would go unnoticed beneath their dense new layer of chocolate. They were wrong.

Surprisingly, Wordsworth, Chester, Carlos, Fumble and Num-Num were not expelled. Wordsworth and Chester had been concealed beneath the table. Carlos had collapsed onto the floor, where he rolled around laughing, until he tumbled out of sight, into the kitchen.

Num-Num and Fumble had taken fright at the explosion and bolted from the tea rooms before the chocolate had fully settled. Fumble had galloped home. Olive had found Num-Num an hour later in the penthouse suite on the tenth floor of the Brighton. She was snuggled up in bed between Lord and Lady Quagmire, sipping pink lemonade and choosing her dinner from the room-service menu. She was most annoyed when Olive insisted she come home. Lady Quagmire was rather disappointed too. She thought Num-Num a charming companion and would only allow her to leave once Olive had promised that she and Num-Num would visit Quagmire Manor before the winter was over.

‘At least my darling dinosaur is safe,’ mused Olive as she turned off the garden hose. ‘But so many others are gone.’ She wiped the back of her hand across her eyes. ‘Silly,’ she said. ‘No time for tears! One must think brave and practical thoughts.’

Shaking her shoes and squaring her shoulders, Olive marched inside. ‘I shall do my best to ensure that the Queen’s visit is a success, wave Thistlebloom farewell, then head off into the big wide world to find my friends.’ She halted, put her hands on her hips and stamped her foot. ‘And I will find them. I will bring them home and –’

‘Good evening, Orange.’ Pig McKenzie leered at her over the top of a large cardboard carton.

Oh dear! She had forgotten about the pig. ‘My name is Olive, not Orange.’ The pig smirked.

Olive gasped. ‘Is that enormous carton full of chocolate?’

‘Absolutely!’ snorted Pig McKenzie. ‘The kitchen staff at the Brighton are rather down on chocolate after today’s little episode.’ He plopped the carton onto the floor and rested a hind trotter on the lid. ‘So, generous pig that I am, I offered to dispose of their remaining supplies. This is the first of twelve boxes of fine Belgian chocolate that will be delivered to my cupboard in the next twenty-four hours.’ He stretched and scratched his belly. ‘It’s a tough job disposing of so much chocolate, but somebody has to do it!’ A trickle of saliva dribbled out the side of his mouth.

‘You greedy porker!’ snapped Olive. ‘You’re going to eat it! All by yourself!’

‘Orange, Orange, Orange!’ The pig sighed and pressed his trotter to his heart. ‘So quick to judge. No, no, no, no, no. These boxes of chocolate shall be sent to Switzerland to feed the starving millions. Just another charitable deed by the Humble Pig of Groves.’

‘There are no starving millions in Switzerland!’ cried Olive. ‘The Swiss are swimming in chocolate . . . and cheese.’

Pig McKenzie narrowed his eyes. He picked up the carton and waddled into his cupboard beneath the stairs. ‘Sayonara, Orange!’ he grunted and slammed the door.

‘My name is not Orange!’ shouted Olive, and she might have been tempted to run forward and indulge in mindless acts of violence with the pig’s door had Shaggy not stuck his cold, wet nose in the back of her knee.

‘You’re still here!’ she said. ‘Shouldn’t you be going home? It’s awfully late.’

Shaggy scratched his ear with his back paw. ‘I live on my own in a dark and lonely alley where complete strangers call me Go-On-Get-Away-With-You or Pong-You-Stink! I’d like to stay here . . . if that’s alright.’ He lifted his chin to add, ‘And it’s not true what they say.’

‘What do they say?’ asked Olive.

‘That I knock rubbish bins over and spread the contents all along the footpath.’

‘Oh!’ Olive smiled.

‘Okay, it is true,’ Shaggy confessed. ‘But only because, sometimes, if I look really hard, I find half-eaten pies . . . and muffin papers with crumbs stuck to them . . . and yoghurt cartons that aren’t quite empty.’

Olive knelt down beside him, placing her arm around his neck. ‘Friends, old or new, are as precious as gold,’ she declared. ‘And right now I could do with a brave new friend by my side.’

Shaggy stuck his wet nose in her ear, then licked her chin.

The deal was sealed.

Olive headed upstairs to bed, a hand resting on the dog’s head. The dear creature oozed affection and devotion. He also oozed fleas and a funky smell, but that is beside the point. Dogs are marvellous judges of character and this one had quickly deemed Olive the type of child one would follow to the ends of the earth – or to the bowels of a building, as the case may be.

However, I am running ahead of myself.

As Olive climbed the stairs, she was taunted by strange, muffled sounds. And not just from the dog. There were mechanical whirrings, a clunk, two oinks, then a continuous rattle with a chug-chug-chug wheezed over the top. She looked up and down, around and about, but could see nothing unusual. Unless one counted Mr Pennyfetherill and Mrs Groves, who were draped in pink feather boas, tangoing along the corridor.

Her arrival at the third-storey landing was marked by a loud bang.

‘Oh!’ cried Olive. ‘Surely that bang came from inside the wall!’ She scratched her chin. ‘But it can’t have. It does not make any sense.’

Shaggy blinked and flicked his tongue across his nose.

Olive walked over to the little door labelled Laundry Chute, opened it and stuck her head inside.

‘Nooo!’ She leapt back and shook her head. ‘I must be going bonkers. Why, I could have sworn that I heard someone reciting an alphabetical list of rude words!’

Gingerly, Olive stuck her head back through the little door. ‘How bizarre!’ she murmured. ‘Now I can hear that clip-clop sound again!’

She leaned a little further forward. ‘And now I can hear a grunt and a snort from behind me and – WHOAH!’

Her legs were lifted off the ground and, before she even had time to kick or protest, she found herself flying headfirst down the laundry chute. She slipped and slid, zipped around corners, shot to the left, plummeted to the right, squealed like a baby and flew face-first into a large pile of dirty laundry. Shaggy was right behind her . . . then suddenly on top of her . . . then tangled in a sheet beside her . . .

Olive scrambled to her feet.

‘What a surprise, Olive! We were not expecting you to drop in at this late hour!’ Mrs Groves sat on the washing machine, knitting an ugly green jumper, her legs kicking back and forth. She blinked, blushed and smiled sweetly.

‘We?’ asked Olive, then squealed with delight. ‘Tommy! I thought you were expelled! And Pewy Hughie!’

‘Hi, Olive!’ Tommy pulled a dirty sock from each nostril and waved them in the air.

‘Hey there, Olive!’ Pewy Hughie grinned.

‘Ouch! Who bit my bottom?’ cried Olive. She spun around. ‘Beauty!’ Throwing herself at the large black horse, she hugged and kissed, laughed and sobbed. ‘My dear, dear friend! How glad I am to see you!’

‘Awk!’ Cracker the parrot landed on Mrs Groves’ shoulder and continued with his alphabetical list of rude words. He was up to the letter X, which might sound challenging, but he managed to find no less than five words. It helps, of course, if you can swear in Peruvian as well as English.

One by one, the expelled students crept out from behind laundry baskets, the clothes dryer, piles of dirty sheets – Peter, Diana, Flick the goanna, Ivan, Splash Gordon, Bullet Barnes, Steve and George the hermit crabs, Elizabeth-Jane the giraffe, Anastasia, Alfonzo, Reuben the rabbit, Valerie the owl and Helga the hippo.

Actually, Helga did not creep out. She skated out . . . on her enormous bottom . . . on a wave of sudsy water she had just drained from the washing machine. ‘Wheeeeeee!’

Olive spun around and around, drinking in the sight of her friends. Her wonderful, beautiful friends.

She smiled and laughed and bunny-hopped like a rabbit on a pogo stick. ‘I thought you were all gone!’ she cried. ‘Expelled.’

‘Oh, we’re expelled alright!’ said Peter. ‘But definitely not gone.’

‘Oh no, no, no, no, no!’ babbled Mrs Groves. ‘Not gone. I do not approve of students going away. The idea is simply too awful. Once a Grovian, always a Grovian. That’s what I say . . . and I mean it!’ The headmistress smiled and nodded and knitted so rapidly that a pair of underpants from the laundry basket was whipped up with her yarn and became entangled in the front of the jumper she was creating.

‘But how have you survived down here?’ asked Olive. ‘Weren’t you bored?’

‘Oh no!’ cried Diana. ‘We have been playing lots of games – Scrabble, Dirty Linen Hide-and-Seek, Twenty Questions and Pin the Tail on the Hermit Crab. And Mrs Groves has been teaching us all to knit.’

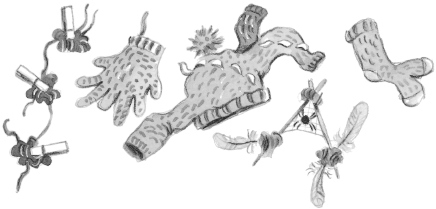

The naughty boys, talking animals and circus performers all nodded. One by one, they showed Olive their knitting projects, blushing with pride and, occasionally, confusion. For while some items were obviously socks and scarves, there were also seven-fingered gloves, beanies with sleeves, and strange but fascinating collages of knotted wool, knitting needles, shoelaces, pegs, feathers and spider webs.

‘But you must be starving,’ said Olive.

Beauty pushed a laundry basket full of jelly beans to the centre of the basement. ‘Leftovers. From that maths lesson on capacity.’

Olive scooped up a handful of jelly beans and let them trickle through her fingers. ‘This must be Blimp’s idea of heaven!’ She laughed, then suddenly stopped. ‘Hang on a second! Where’s Blimp?’ Her stomach knotted. She gasped. ‘And Star? Where is Star?!’

And our heroine, who had been so admirably brave and resilient up until now, turned as white as a sheet. She sniffed, then whimpered, then collapsed to the floor and howled.

Tears.

Wobbly mouth.

Lusty sobs at the back of the throat.

Breast beating.

Puffy eyelids.

And copious quantities of mucus.

It was all terribly distressing.

Especially the mucus!