Resurrection

It is the time of resurrection,

The time of eternity,

It is the time of generosity, the sea of lavish splendor.

The treasure of gifts has come, its shining has flamed out.

See, the rose garden of love

Is rising from the world’s agony.

—Rumi

*

Who are the people who run toward the pain, the catastrophe, the chaos? Who are those people whose DNA or family mantra determine their role and their talent to solve the problems, salve the wounds, unravel the chaos? Who can put out the fires, put the house and lives back in order, soothe the wounded heart and soul, or sing a lullaby and put a child’s fears to rest?

If over the years of your life your first response is to run toward the fire, take a breath and resolve the catastrophe or chaos, and you are talented at that role, if it comes naturally to you, then I suspect that you are the nurses, doctors, teachers, police, therapists, and caretakers of all kinds. I applaud you and thank you for your service!

My experience, however, is that there are enormous numbers of courageous, compassionate, and committed people who serve others, often at the expense of themselves and their families. I would like to explore the lives of these people, who “run into the fire.”

Stacy’s Story:

WITNESS TO THEIR PAIN,

BECAME HER PAIN

I fell in love with Africa the minute I stepped off the plane in Freetown, Sierra Leone in 1995. From that moment I was hooked. Africa was in my blood: the smells, the feel of the air, the feeling of sacredness, the people, oh, the people. I am still awed by how these wonderful people can go through such hardships and still laugh, be gracious, generous, kind. I loved working with the local nationals. Most of our work staff was made up of a large number of host country nationals. Later, when I worked in Afghanistan, I loved the work, but my true love was and always will be Africa.

Stacy is a delightful, charismatic woman, filled with energy and an all-consuming passion for whatever life puts in front of her. I first met Stacy in 2016 when she joined a five-day intensive retreat that we hold monthly through our treatment and training program, Spirit2Spirit. The venue was a glorious lakeside bed-and-breakfast on Lake Weir in Ocklawaha, Florida. The venue is important because the trauma work we do during those five to ten days is very deep, experiential, intimate, and very emotional. Intimacy is created as a result of the depth and honesty that is felt in shared pain and joy. As we learn to trust, we’re able to risk telling our story, and be open to all possibilities for a healthy future.

Stacy attended our intensive retreat to explore ways she could let go of the pain of her inability to cure her daughter of her drug addiction and trauma history, which was emotionally, physically, and spiritually overwhelming her. Stacy’s daughter had been in multiple treatment centers and had many near-death overdoses.

At the beginning of an intensive we ask, “What would you like to happen for you this week?” Stacy’s response was to help her daughter “achieve recovery, or find a way to let go.” Stacy is petite and bubbly, enthusiastic and passionate at her best. At the beginning of this intensive and for the next two sessions Stacy’s most common response was “Roger that”—the lingo of her field of work.

“Stacy, can you describe your daughter?”

“Roger that.”

“We’re going to break for lunch, would you like a sandwich?”

“Roger that!”

As light-hearted as I make it sound, those responses were the immediate reactions from a woman who worked for twenty years in war-torn countries, part of the support personnel for peacekeeping missions all over the world. In other words, she was essentially a soldier without a gun.

Stacy reported that she and her sister grew up in a family dedicated to service for others. Raised in Port Arthur, Texas, during a time of racial strife, the sisters were taught that their life’s purpose was to help others less fortunate to have better lives. Her father was a newspaper editor and her mother was a reporter. Their editorials and articles condemned segregation and supported equal rights. After one such editorial, a brick was thrown through a window of their home. Threats were made and the girls were terrified, but they were expected to go to school the next day and brave the bullying and taunts.

When asked what dinner was like in her family, Stacy said, “We talked about politics, justice—or rather the injustice—and civil rights!”

Now let’s unravel the elements of a first-responder’s life. It comes as no surprise to me that Stacy would ultimately devote her life to others, “a soldier without a gun,” a mother without a how-to guide for single parenting, and without an understanding of the breadth and depth of family trauma. Stacy was born and bred to serve. She had an amazing upbringing, but focusing on service to others often leaves no focus on self. The automatic reply of “Roger that!” in the “real world” (i.e., back home, outside of a war zone) spoke to me of burnout, numbness, and undiagnosed PTSD.

Stacy was asked to put her daughter’s “work” on the side, and dive into her own story. The people at this intensive were from different regions, cultures, and socio-economic backgrounds. However, the commonalities were the depth of their isolation, personal grief stories, inability to be in truly intimate relationships, the need for validation, low self-worth. Each person was either emotionally erratic or numb. In short, this was a perfect group for healing, as group members can be the instruments for each other’s healing.

Stacy was truly numb to the events in her life that she had been experiencing for the last twenty years and, as do many of us in the caring professions, she often reverted to “dark humor” to alleviate the stark reality of a situation. Witness her caption to her collage.

Flat Chick Bridge

The story is that in April 1996, fighting broke out in Monrovia and Monrovian citizens scaled the embassy wall for protection. Thousands of people were sleeping on the grounds of the embassy. The embassy ran out of water so it was my company’s job to make the water runs. The water runs took us across the bridge; on the other side we had to fill the water truck. During the water runs we had to radio in our location so that when we got close to the embassy they could open the gates for us. We had to give landmarks. One of the landmarks on the way back was “Flat Chick Bridge.” There was a woman shot on the bridge and she died there. The bridge is narrow and we had no option but to continually drive over her body. Hence, “Flat Chick Bridge.” I call this survivalist humor, which many will not understand unless they lived it. Otherwise, it was just too much too take in, and we would fall apart—and to fall apart meant life or death. The last landmark was “Dead Man’s Curve.” When we radioed this in, they would know to open the gates because this was right outside the embassy.

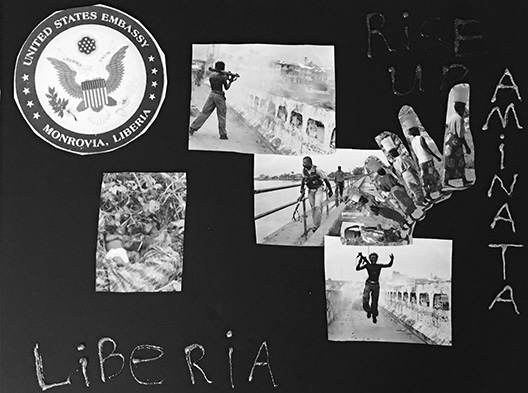

I have thought about this woman on the bridge for years. Judy gave me an assignment; she asked me to give her a name and think of her story. I named her Aminata. Judy asked me to show Amanata how I wanted her life to be. In the collage I show the environment around her and what it was like during the fighting. There was shooting on the bridge and she was trapped. However, I show her rising up and continuing to walk home with the water she has for her family on her head. Aminata was put to rest by this assignment and I was able to have peace around her.

Flat Chick Bridge is symbolic of the many ways that we ratchet up our capacity for layers and layers of trauma, until the tiniest bit of stress can bring us to our knees praying for relief.

The body, mind, and spirit experiences stress and trauma at the sensory, cellular, and visceral, level so we cannot discount our own trauma as “not so bad.” When we judge our own trauma experience, we do so at our own peril.

The Babies of Darfur

One day in Darfur we had to go out to a village that had been attacked by the Janjaweed (Sudanese government militia). The Arab Sudanese were eliminating the black Sudanese: genocide. We landed at the village in the helicopter. Some of the tukels (round, thatched huts) were still smoking. We could smell charred wood and flesh. I’ll never forgot the smell. There were several dead, including children. All the time I was walking through the village I wanted to pick up the charred skeletons of the babies, but I couldn’t; we could not disturb the scene because it was being investigated. We spent several hours in that village.

During an intensive, we did breath work. This is where you breathe deeply for about an hour and music is played. I thought this would be silly but I was willing try. Whew, was I wrong. Images started appearing to me during the breath work. They were of this village, something I had forgotten for a long time. The baby skeletons appeared and all I wanted to do was pick them up. Much to my embarrassment, I started saying over and over, “The babies, the babies, the babies.” Visually, I was able to pick up those charred tiny skeletons in that village and put them to rest the way they deserved. I knew I could not bring them back but they deserved dignity.

I had held these stories inside me for twenty years and had not shared them with anyone. Through these intensives I have not only brought the stories back to myself, but also to the Universe. These people who suffered in Africa deserve for their stories to be told.

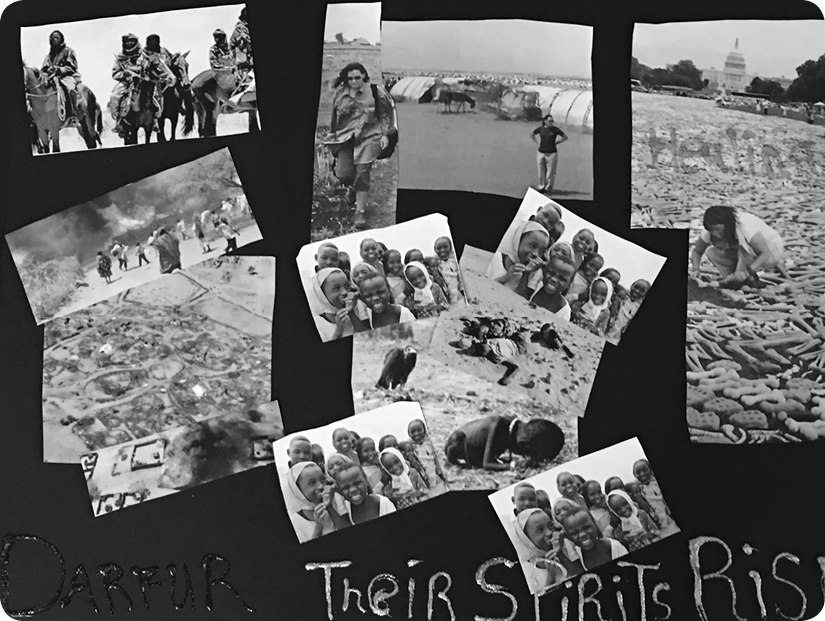

The collage depicts the Janjaweed (men on horseback) and the burning village, the dead. The pictures of the living, smiling children I have around the dead, to me, are the spirits of the dead living on. The picture of me laying the bones is an event I was involved in on the National Mall where volunteers lay millions of “bones” from the Capitol to the Washington Monument to represent all that died in genocides. It was a very healing process.

This woman, who bravely steps onto bloody ground, is living her life one day at a time without imagining that there is anything extraordinary in how she’s lived her life. Stacy is following the family theme, repeated at dinner, “How are we going to save the world today?”

And so she finds herself in Liberia, Sudan, South Sudan, Afghanistan, Washington, DC, in the fifth Family Week at another treatment center to be there for her daughter, or at her mother’s bedside—following the family job description of “doing” for others.

That is an amazing gift, the ability to organize and solve problems and walk through one crisis after another, however, when she finally stood still and breathed, her life began. When Stacy stops and really breathes, she experiences her extraordinary life.

She and her daughter, Kenzie, have done tremendous work together and separately. They are now able to not be co-dependent (well, not nearly as much) on one another, accept each other where they are, and enjoy life. Kenzie is sober and expecting a child in the fall. Now, is that not living?

We each have a story and if we stand still and breathe in and out, slowly and consciously, we can be brave and experience our story with all our senses and all of our emotions, and not be afraid to welcome the variety of the guests who come to our door throughout our story. We are no longer hostage to our trauma story and can embrace our survival, triumph, and grace, and create a glorious story of our choosing.

Our stories are the stuff of Tom Clancy, Nicholas Sparks or John Grisham. These trauma and addiction survivor stories are to be celebrated because they inspire us to our very core.

Wico’s Story:

A HERO’S STORY

“Woohoo Wico! Yay Wico! We’re so proud of you!”

These were some of the hoots and shouts for Wico, an 82-year-old Dutch Indonesian-American hero. Wico was an integral part of a trauma intensive at The Refuge along with twelve other people from nineteen to eighty-two years old, from twelve very different backgrounds, but with a dozen very similar responses to their histories, their trauma stories.

Wico, the oldest of the group, was referred by his incredibly loving daughter and son-in-law, who recognized the extreme emotional pain, sadness, and depression that had overwhelmed him. After a life of love and joy and apparent success, Wico was on the brink of despair and was suicidal. Wico’s son-in-law David approached me with the thought that perhaps a trauma intensive would help to save this beloved man. David is a colleague in our industry and recognized the imperative need for an intervention. Wico and his beautiful wife Evie were so willing to try.

I’ve been blessed to work with many war veterans, but Wico’s life moved me in a way that demanded that I share some of his story with the permission of his family. Wico did not volunteer to go to war; he was violently thrown into the tumult and terror of the Second World War as a child of ten in Dutch Indonesia. So, although it wasn’t his choice, Wico is one of my heroes who “ran into the fire.”

Research shows that the huge numbers of veterans of all countries in the coalition forces of Iraq and Afghanistan who are committing suicide as a result of wounds of moral injury (discussed in Chapter 3) are far outnumbered in ratio by the number of suicides by WWII veterans, now in their eighties and nineties.

There is no doubt that this silent, great generation came home as heroes but never discussed or shared their deepest pain, sadness, and remorse about the war, and how it impacted who they were, and how they survived. Their reluctance to share their pain and secret wounds trickles down through the intergenerational matrix, seemingly without rhyme or reason for behaviors. For instance, my silent, brooding grandfather—I don’t know his history, his pain, what silenced him. What silenced my three brothers-in-law, all veterans of Vietnam?

Wico also kept silent about the despair that began to envelop him, as his long-term memory became louder than his short-term memory, as the horror of being a fourteen-year-old prisoner of war became much more in the forefront of his heart.

Wico became intimate with his group, younger men and women who were fighting their demons in the here-and-now, also consumed by the secrets of their past. I am always amazed at the intimacy that transpires in five short days, the trust and courage to share the deepest and the darkest in order to be and live free. That’s what happened for Wico and his peers in pain and trauma. They each shared their stories through experiential exercises, telling their stories in many different ways through art, psychodrama, Somatic Experiencing, and adventure therapy.

The power of the group experience is in my estimation much more effective than individual work, and that’s what I witnessed with Wico and his group. This brave man wanted to live more than he wanted to die. So he took a leap of faith and trusted his secrets with these men and women, who showered him with love and celebrated his courage by sharing their secrets and pain as well.

Wico has written his life story and it is poignant and intense. He blessed me with a copy and gave me permission to share his story. And I would like to share some of it with you now. His story deserves its very own book, perhaps even a movie.

I regret that I cannot begin to do justice to Wico’s incredible story but I will give you pieces and pray that his whole story can be published because his survival story is a gift.

Wico’s Story • 1928–1931:

WAR THROUGH A CHILD’S EYES

My father took a ride in a sidecar of a motorcycle. While riding it, the sidecar got disengaged from the motorcycle. It crashed against a tree. At the time they never heard of wearing helmets, so my father hit his unprotected head against the tree. He was for a long time hospitalized and the best doctors in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) couldn’t help him. He had to go to Holland for treatment. My mother and father went to Holland on two of their furloughs, which they were entitled to once every three years, but the best doctors in Holland couldn’t help him either. In the meantime, his personality changed by the day. He became violent and very moody. According to Hetty [Wico’s older sister, Wico being the youngest of six] he argued with my mother about everything.

Today we would diagnose Wico’s father with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Wico was born after the accident, so he never knew his father as anything but violent and moody. Wico’s parents were divorced as a result and Wico was raised by his father and a servant, Min. Wico believed that he was born to try and save the marriage but to no avail. His two brothers moved out before Wico could know them They were in a camp as part of an effort to reclaim the jungle in New Guinea. This would later become a battleground for his two brothers and many other young soldiers.

There was a difference of eight years between Wico and the next youngest child, Carlos. Wico shared that at six years old he, his father, mother, and Min, moved by ship, the Kapul Puti (White Ship) to New Guinea. Wico describes Min “as a second father to me; (he) stayed with us through thick and thin.” Wico describes a game that he and another boy who he became friends with, played on the ship.

One of our games was going to our mothers and pulling a string of hair to see which was stronger. I always won, because my mother had strong, thick hair. Another game we did is put a piece of paper at the end of yarn and use it as a kite on the stern of the ship. We had just simple toys. I remember, that I always made homemade toys.

Wico goes on to describe moving into their house:

Our two-story house was built with gedek walls, had a bamboo ladder to get to the second floor, and a hard, earthen floor with no plumbing and electricity. The reason for the second floor is for the torrential rains we sometimes got. The flood could be almost knee deep in the “living room,” but fortunately, it usually only lasted for one day. We had also no bathroom or toilet, not even an outhouse!

I was happy, even without all the luxury we had in Java. I now wonder is this why those Papuan [indigenous people of New Guinea] were happy too, just as I was living in this adventurous world? The end for me came more or less when my parents divorced. I don’t agree with some people, including professionals, who say sometimes it’s better to get divorced for the children’s sake. The children will always suffer no matter what, some indeed more than others. I think it’s up to the parents to keep their disagreement to themselves, even if it hurts them doing so.

My father spent a lot of time with helping me with my school work. It had probably taken a toll for me losing a mother, moving back from New Guinea to Java, moving three times to different addresses in Java, going to three different schools, and this all within one year between the ages of six and seven! In that time, it was a big deal to advance to a higher grade. It’s not unusual that the failure rate can be as much as 15 percent. I was in fifth grade before World War II and never stayed down.

At this point in Wico’s trauma story he describes common themes for survivors: family discord, divorce, health issues, multiple moves, financial and material insecurity, and emotional instability. He also describes elements that create resilience, such as having a steady caretaker in his father, additional loving support from Min, and a joy for play and the world around him.

December 8, 1941–August 15,

The war in the Dutch East Indies started when Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, which was December 8, 1941 Dutch East Indies local time. The Dutch government, in exile, declared war that same day on the Japanese. I remember my father being glued to the radio and taking in the bad news, one story after the other. I saw his gloomy face, especially after the announcement of two English battleships, the Prince of Wales and the Repulse, that were sunk by the Japanese in the first days of the Pacific War. We were told to glue strips of paper on the windows to avoid them from shattering if we were bombed. The children must carry at all times a small bag and an eraser to bite on and earplugs, to be used if there was an air raid. If this happened during school time we had to go to the nearest trench, which were dug in many places including school grounds. Many trenches were used by kids as swimming pools during the rainy season!

War is a horrifying experience for anyone, but for children the fear and terror are multiplied a thousand-fold. The remnants of our family history, both known and unknown, continue to drive the patterns of behavior, communication, the condition and style of our relationships, what we share and don’t share with the people we love, and who love us.

Our ability to be truly intimate depends on how deeply we are willing to share our truths with one another. This journey of exploring our family history allows us to open up to the possibilities of who we are and who we can become.

On my last visit with Wico, his wife of sixty-one years, Eveline (Evie), Ingrid, his daughter, and David, his son-in-law, there was such joy and love and I felt so honored to be audience to Wico’s storytelling, Evie jumping in with additional insights. They have been through so much history together and have raised a family who love and respect and care for them without reservation.

Wico’s willingness to put his ghosts to rest has given a gift to his family as well. The next pieces I want to share are more difficult to hear; our role is to witness for one another and grow and embrace our common pain and our common joy.

Overall, I didn’t have a pleasant youth, but the years 1942 through 1947, up to seeing my siblings after my release from prison camp, were the worst of my entire life. No doubt also, that some events, that I remember and some I don’t, such as not remembering visiting my father held by the Kempeitai (Japanese Military Police), will probably affect me for life. My problem was more emotional in my later life, looking back at what happened in those earlier years, when I was fourteen. (I am now seventy-seven in 2008). I have never ever told anyone in detail what happened to me in those years, only a bit here and there of some events. Since I haven’t felt good for almost two years, I thought to tell my family doctor about those troubled years. The doctor referred me to a psychiatrist. The diagnosis I got from the psychiatrist was severe post-traumatic stress trauma and I’m being treated for this.

As you can see, Wico held his secret pain tightly wound inside his soul and his heart for sixty-three years, never telling anyone until he had no choice. Writing his life story was the beginning of saving his wounded heart. I met Wico four to five years ago and as he and his family reported to me, so much changed; suicide was no longer a solution. Sharing his story, and experiencing it with others is what healed him.

So to continue, Wico speaks of his father and nine other men being picked up by the Japanese Military Police. Later he discovers that only two men survived; his father died.

Wico did not go to school from 1942–1947, a huge loss to this young boy who thrived in a teaching environment. He survived by being part of a community that looked after each other and he developed extremely good survival skills, but he was just a boy, who like so many others over the decades and centuries had to do whatever it took to survive.

Wico and the other boys were drafted for indoctrination classes called seinendan, part of the Japanese youth movement. The boys marched with bamboo spears to “defend from invaders,” watched war movies, and learned how the Japanese would win the war on the ground, in the air, and on the sea.

The occupation and oppression had changed all of us, in security and fear, especially around the Kempeitai [Japanese military secret police]. Casual friends could not be trusted. On September 17, 1945, Dutch citizens began being picked up. The police ordered me to go with them for interrogation, which actually meant that they never release you afterwards! I was ushered into a prison cell with at least fifty other inmates, a cell probably intended for fifteen or twenty inmates. I was issued a 2x6 tikar (palm mat) and told to find a place.

Wico goes on to describe his surroundings and I’ve watched enough movies to be able to envision this horrifying scene. What is overwhelming to me is to imagine my one-year-old grandson or fifteen-year-old granddaughter having this same God-awful experience, the kind of hell that Wico and so many endured, and so many endure even as I type these words.

More horrifying to me is, even knowing the resilience and strength of character my children and grandchildren have and that they would endure, they would still be changed forever. That is the lesson of trauma survivors; we are changed forever by our life experiences, but we are capable of turning the trauma experience into a life of purpose as well.

I haven’t taken a bath in over a year! Having dysentery is like a death sentence for them (patients frail and weak after being held in Japanese camps and rearrested). One died even on my watch! Can you imagine how I felt as a fourteen-year-old kid? I was so afraid I would get the same disease. I still don’t understand how I didn’t get sick in prison . . . someone must have watched over me. My father? No soap to wash my hands with. Eating out of bedpans used by dysentery patients. The toilet always had a wet floor and was dirty. None of us had shoes, except maybe two or three older guys. We ate with our hands— we had no utensils—and we went to bed dirty. We slept on the tikar on the concrete floor. The tikar was infested with bedbugs and we had a constant battle with the lice that lived in our clothes and hair. Every time I thought how miserable life was, I always thought it was better than having dysentery. There was another boy in my cell, probably one or two years older than me. His father had dysentery and died later. Can you imagine how he must have felt? I thought how lucky I was, even without any family in prison with me, but at least I have my father. Not knowing of course, that he died a year earlier in a Kempeitai camp. It must have been at that time that I became a thinker, that is, if I feel bad, there were always people worse off than me. If I was in pain, I compared it with worse pain I had in the past. The only time this comparison didn’t work was when I was passing kidney stones forty years later.

Wico, the “thinking” man, had created a resilience dialogue, a positive outlook that has saved many survivors and certainly saved him. He had the ability to look beyond the present event to a time of hope. And Wico had other survival skills, the child in him continued to create games that kept his mind active and engaged and relationships.

One positive thing I got from my imprisonment was that I think it made me a better person. We picked up pebbles and sticks (on our half-hour break) that we used for playing checkers and chess. I remember playing cards and checkers with my father at age seven and I thought I was playing checkers very well by beating him a couple of times. Later, I found out that he was the best checkers player in the family. We had a champion checkers player in our midst in prison. In my eyes, he was an “old guy” of twenty-seven. He beat us for months until I found a strategy to beat him all the time. My strategy has always worked for me. I was using it thirteen years later in the Air Force against the base champion. The first play ended in a draw, but I won the following two games. Beating the guys in checkers in prison did me good, because the winner got the banana peel with the strings still attached.

I can almost see the twinkle in Wico’s eye as he shares his triumph—that spirit, the innate joy of life shining through.

One day, we received an American Red Cross package that we had to share with four persons. Later we found out, that we were supposed to get one package for every person! Everybody who reads this, please donate every time you see an American Red Cross person asking for a donation at Christmas time. I have never seen since that time how meticulously we divided everything in four portions. What I liked most was the cheese, corned beef, and chocolate. It was almost like a ritual how we split the chocolate bar in four pieces. We first cleaned the concrete floor as best we could, then one was chosen who was going to attack the bar, then when we all got our share, we would hoom-pie-pa (rock-paper-scissors). The winner got the crumbs, but they were so small, that licking of the concrete floor was the only way to get it all. Remember how the part about going to the toilet on the filthy wet floor on bare feet?!

In my mind’s eye I can envision this boy, fourteen, adapting to this world, just as Victor Frankl described in Man’s Search for Meaning:

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing; the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

The worst thing for me that happened at this time that I will never forget is the death of one of ours. He had reached the end of a venereal disease. He contracted the disease before he was interned. Without any medicine, he must have had a terrible pain before he died. The screams from the pain, especially at night before his death was unbearable to hear. I was so afraid that one of us I shared a room with, would get any kind of disease especially dysentery and also die from it. I got my first sex education at that time from the guy that slept next to me. He told me that he too had another kind of a “woman” disease. Hearing all of that, no wonder that women were considered to be evil, causing all those problems. Needless to say I had negative feelings against women.

After the death of this other prisoner, Wico and his mates were moved several more times and then finally, two years after that last move, they boarded a train.

The train ride brought us after almost three long days to freedom! I’ll never forget the time seeing the Dutch flag again waving in the wind, after not seeing her for so many years. We all cried and even now writing this down I still get emotional.

Wico’s beautifully emotional story continues as he meets his Evie, Eveline, whom he would marry and celebrate sixty-one anniversaries together.

I had passed by the van Ommerens’ house and I saw Evie playing in the street. We didn’t have time to talk. Can you believe it? She was thirteen and I was sixteen. This was the first time I saw my future wife, wow! I went to the Red Cross, as so many of us also did. I found out that Hetty (my sister) and Carlos (my brother) were in Surabaya and Teddy (my brother) in Bali. They couldn’t give me information about my parents and my other brother, Ewald. I later knew why; they didn’t make it through the war. Hetty told me that my father died in a Kempeitai prison. The Kempeitai were notorious for their cruelty. He died April 18, 1945 after being tortured. My father was buried in Semarang honor cemetery which is maintained by the Dutch government, comparable to Arlington National Cemetery.

My mother died October 1944, when she and others were moved to another prison camp and had to walk through the jungle of New Guinea, weak from malnutrition. She was left somewhere in the jungle. We don’t know how and we don’t know the date she died. She wasn’t buried anywhere. Ewald, my brother, died also in New Guinea’s jungle December 31, 1942. Teddy and Ewald were guerilla fighters during the Japanese occupation in New Guinea. They received the highest medal one can receive from the Dutch government. There are three books written (in Dutch) about their ordeal fighting in the guerilla war in the jungle.

Wico’s story is a prime example of intergenerational trauma, and a wonderful example of survival and resilience. His was a life well-lived as the patriarch of his family, a Dutch citizen and a great American, a success in all areas of his life, and a trauma survivor who asked for help and renewed his spirit as he shed his secret pain. Wico, I love you and I bow to your shining spirit.

Wico passed away November 5, 2016, in Ocala, Florida. Born January 14, 1931, in Java, Indonesia, he was a 1954 graduate of the Royal Netherlands Military Academy, the Netherlands and the U.S. Air Force Flight School, class of 1954. He flew F-84F fighter-bombers under the name “The Flying Dutchman.” He and Eveline immigrated to the U.S. on January 7, 1961, under the shadow of the Statue of Liberty, and raised three children. Wico and Evie settled into Oak Run and enjoyed a retired life of tennis, line dancing, shuffleboard, and regular visits from their children and grandchildren. They traveled the world together, became U.S. citizens, and visited all fifty states. Wico lived life to its fullest after surviving POW internment camps and the horrors of WWII in Indonesia.

Wico was at The Guest House, welcoming and greeting each arrival and entertaining them all. He was guided in his life by each trauma and sorrow, but lived to embrace the fullness of his life. I honor Wico and his family, their love, care, and courage, and I’m excited for the generations that follow.

The final experience of our intensive is the “leap of faith,” a ropes course challenge. Each group member gets into a harness (safety first) and then climbs what is essentially a telephone pole, and then they stand on the top of the pole, about twelve inches across. They take a deep breath, jump into the air, and grab the trapeze across a six-foot space. Woohoo! The climb and the leap can be a life-changing experience, moving through fear, making a decision, taking a breath, and then jumping off to the hoots and hollers and support of your new tribe, who know the deepest and darkest of your pain and encourage you to leave it behind you now.

Tremendously exhilarating and terrifying at the same time, this challenge is a perfect drumbeat to these folks who have faced their trauma story, unraveled the story, and are at the beginning of changing their lives forever in a positive way. Because he was an eighty-two-year-old on kidney dialysis, Wico could not climb the pole. But his group was adamant that he should fly, so they harnessed him and hooked him to a pulley, and together they pulled him up to the top of the pole, yelling and cheering and applauding as he hung in the sky, making his own leap of faith. Woohoo, Wico, well done!

Father Joe’s Story:

MIRACLES HAPPEN HERE

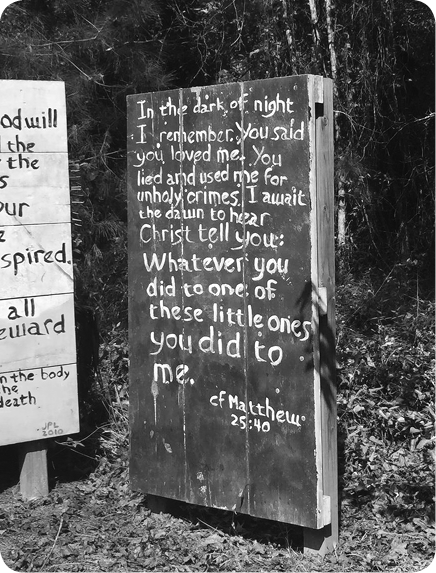

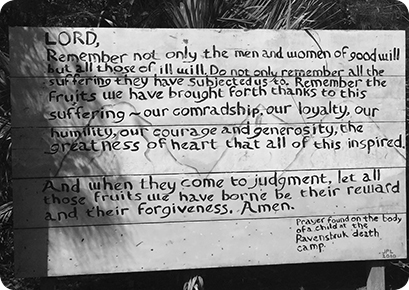

Father Joe created a lovely memorial to his trauma resolution and self-forgiveness on the Memorial Trail at my former treatment center, the Refuge. He made these scripture panels as part of the trail. Father Joe spent five months working through his years of pain and moral injury. From the depth of Joe’s trauma story, you’d be forgiven for believing that he couldn’t heal. However, Joe had an overwhelming desire to have the life he deserved, the life he dreamed of. I’ve spoken to and seen Joe over the years, but more than anything I’ve reveled in Joe’s life as celebrated on Facebook. So I e-mailed Father Joe and asked if I could use his story and his beautiful memorial and he said “Of course.” Here’s Father Joe’s list he sent in an e-mail:

List of My Trauma History

- Molested by my dad as a toddler

- Near drowning at age three

- Growing up in a home dominated by Dad’s alcoholism and rage

- The death of my brother, who was seventeen, and my aunt, from an auto accident, when I was thirteen

- Eight years of being sexually exploited by a priest during my high school and college years in seminary.

- The pressure to stay closeted as a gay man my first fifty years of life.

- An array of betrayals by church officials and the institution of the church during my one year of seminary and my twenty-four years of ministry.

- Ten years as a diocesan official having to help defend the church in the midst of the sex abuse scandals and lawsuits, as well as being called upon as a change agent in implementing reforms for child and youth safety.

- Seventeen years of active alcoholism.

- Extensive history of compulsive behavior.

- Overeating

“My lunch hour is almost up,” Joe concluded in his e-mail, “so I’ll need to follow up with my time at the Refuge and life in the six years since.”

The most amazing thing about Joe is his trauma history list. Not only did he complete it on his lunch hour, but there was no longer a “charge” or “energy” to his trauma overshadowing Joe’s life.

When our guests come to treatment this “list” ruled their lives in multiple ways. Often the “list” was a series of secrets that are “stuffed away in a box,” “pushed down deep, “there is “no memory,” “just a feeling of yuck.”

Often the list drives or “creates” every behavior—the self-destructive behaviors, such as the addiction—in order not to feel the overwhelming feelings. So when Joe can reel off his list of traumas, it speaks volumes. It means there is real trauma resolution and the past no longer consumes Jim’s present. It means that today, tomorrow, each day can be lived fully in every moment and in healthy, joyful, loving relationships.

Joe is no longer a priest; he courageously relinquished his collar to live in his integrity. I saw Joe live in faith, start over without a job or role that defined his purpose. I watched and experienced Joe grow in his spirit and grace and find purpose that has him continuing to run into the fire and help others.

He’s joined the Gay Men’s Chorus, he blossomed in his relationships, embraced true love and commitment, and found and married his soul mate. It is delightful to see the joy and playfulness in his life today. Joe’s experience proves that there is life after trauma resolution. I love the power of healing, and Facebook gives me joy every day. I am continually reminded why I love this work . . .

it’s because miracles happen every day when we can, as Rumi invites us to, “Welcome and entertain every arrival of each new guest, a joy, a depression, a meanness, a crowd of sorrows, who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture.”

And that’s what happens when our guests come to the work with hope for healing and a willingness to do and feel whatever it takes to reclaim your life. We “treat each guest honorably.” Because “He may be clearing you out for some new delight.” And this is exactly the work that Joe did and the miracle happened:

“The dark thought, the shame, the malice,

meet them at the door laughing and invite them in.

Be grateful for whatever comes,

Because each has been sent

As a guide from beyond.”

Reflective Sketches

*

1) Reading these stories, do you see yourself in the way you care for others over yourself?

2) What family messages did you receive as a child that play out as you live as an adult?

3) As you read these stories, what ways do you envision yourself changing?

4) Did you ever reach a breaking point in your care for others or for causes where you just had to put it all down and put yourself first?

5) What are five ways that you relate to Stacy, Wico, and Joe?

6) What are the ways you see resilience in Stacy, Wico, and Joe?