40

Hsuan-tsung (685–762) was one of China’s greatest emperors (r. 712–756) but was also greatly flawed, as he took little interest in government affairs and devoted himself instead to the arts, religion, and his concubine Yang Kuei-fei. After one of the longest reigns in China’s long history, he fled to Western Szechuan (the ancient state of Shu) in the summer of 756, as the rebel armies of An Lu-shan approached Ch’ang-an from the east. His son, meanwhile, established a temporary capital in Ninghsia province, northwest of Ch’ang-an, and had himself enthroned as Emperor Su-tsung. When the An Lu-shan Rebellion was more or less crushed the following autumn, the new emperor invited his father back, and here Hsuan-tsung euphemistically refers to his absence as having been “on tour.” He also refers to the five legendary strongmen who were traveling through these mountains when they saw a huge snake disappear into a cave and tried to pull it out by its tail. Their efforts caused a landslide that crushed them to death but also resulted in the opening of a more accessible route. As the former emperor reached Sword Gate Pass (Chienmenkuan — 250 kilometers northeast of Chengtu) in the winter of 757, he turned to his attendants and said, “Although the natural barrier of Sword Gate is immense, has its ability to prevent communication since ancient times not depended on its virtue rather than its height?” His comment and the poem he wrote on this occasion were inspired by an inscription left at the pass in A.D. 281 by Chang Tsai. Chang recalled an earlier conversation between Duke Wu of the state of Wei (fl. fourth century B.C.) and Wu Ch’i, in which the duke called mountains and rivers the treasures of the state, and Wu replied that their virtue and not their strategic significance was their true value (Shih-chi: 44). Thus, it would seem that Hsuan-tsung finally realizes that his neglect of state affairs has led to his own undoing.

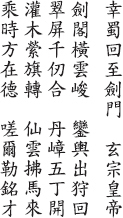

Reaching Sword Gate Pass After Touring the Land of Shu

HSUAN-TSUNG

Our tour complete our carriage returns

to Sword Gate’s cloud-barred peaks

its mile-high screen of folded jade

its cinnabar walls breached by heroes

our pennants weave through a tapestry of trees

ethereal clouds brush past our horses

rising to the times depends upon virtue

how true is this inscription