97

Tu Ch’ang (fl. 1080) was a descendant of Empress Chao-hsien (fl. 950) and held a series of midlevel posts in and around Kaifeng. Here, he visits the ruins of Huaching Palace (destroyed in 755 by An Lu-shan) east of Ch’ang-an, and he likens his journey to that of the relay riders who brought lychees from South China for Hsuan-tsung’s favorite concubine, Yang Kuei-fei. The palace at Lishan was where the two lovers spent much of their time, while the T’ang dynasty went to ruin. Overlooking this testament to indulgence was Chaoyuan (Sunrise) Pavilion at the summit of Lishan. Normally, the West Wind indicates the coming of autumn in China. But west of Hanku Pass it means rain. The tall willows (ch’ang-yang) are interpreted by some as referring to the former Han-dynasty palace of that name, west of Ch’ang-an. But Huaching was also known for these trees, and it seems unlikely that the poet would have confused the two places, which were fifty kilometers apart. This was apparently written while Tu was traveling west to Tienshui to take up his post as senior judge for the province, and he is concerned that his in-laws back at the Sung capital might not have learned the lesson that Hsuan-tsung learned too late. With some trepidation, I have amended the second line, reading hsiao-yun (dawn clouds) for hsiao-feng (dawn wind) to avoid redundancy in the third line.

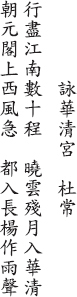

In Praise of Huaching Palace

TU CH’ANG

A journey of countless stages from the Southland ends

with the pale moon and dawn clouds of Huaching

and the West Wind rushing past Sunrise Pavilion

entering the tall willows it sounds like rain