117

Many commentators interpret this poem by Su Shih (1037–1101) as a political critique: the alabaster terrace (which appears in verse 98 as part of the courtyard of the Queen Mother of the West) represents the Sung court, and the flowers represent the reforms of Wang An-shih (1021–1086). In this light, their shadows signify their perceived benefits, the boy stands for the poet or those who listened to his advice, and the sun stands for Emperor Shen-tsung (r. 1068–1085), who supported Wang’s reforms. As soon as the emperor died, the reforms were overturned by Empress Dowager Hsuan-jen, who took over as Regent until 1093, when her son was old enough to rule. Unfortunately, Emperor Che-tsung (r. 1086–1100), represented here by the moon, reintroduced the reforms, and Su Shih was once more banished. While such symbolism might well lie beneath the surface, the poem does fine without such baggage.

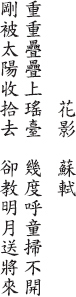

Flower Shadows

SU SHIH

Layer upon layer on the alabaster terrace

I tell the boy to sweep them up in vain

just as the sun takes them all away

the full moon brings them back again