3

Whenever I arrive at a new city for the first time, I scour the map and read through the guidebook in order to find the centre point from where the rest of the metropolis circles. As a historian, I look to see how a city tells its story through its buildings and architecture. It is as if the spirit of the place is captured, like whispers, within the stones of the great buildings.

In 1817 the French author Stendhal visited Florence and suffered from a bout of inexplicable dizziness, fainting and even hallucinations. As he wrote in his diary of the tour: ‘I was seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart … I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground.’1 The sensitive author was overpowered by the artistic wonder of the city, the crucible of the Italian Renaissance, where within a walk of a few hundred yards one can come across architectural masterpieces from Brunelleschi’s Duomo and Ghiberti’s Sacristy of Santa Trinita to the façade of Santa Maria Novella by Leon Battista Alberti as well as some of the most beguiling work by Michelangelo; meanwhile in the Uffizi Gallery, where Stendhal had his first fit, one can see works from Cimabue, Giotto, Pisano, Fra Angelico, Botticelli and Leonardo. In 1979 the Italian psychiatrist Graziella Magherini named the condition Stendhal syndrome, having observed over a hundred similar cases of urban vertigo.

Like all tourists, I begin my sorties around the centre by charting the great public spaces and most notable buildings – a city advertises itself and its power through grand squares, its cathedral and palaces. It is these places that become your compass as you learn to navigate the unfamiliar cityscape. Thus when I arrived at the train station in Florence for the first time, I headed towards the exquisite Santa Maria Novella, and then went in search of the Duomo and from there was able to make my way to the hotel. As I wandered in awe for the next few days, I crossed the Piazza della Signoria as if it were the starting point of all journeys. In time, streets and features – a church, a statue, a café – became as familiar as places that I pass every day at home. Yet the buildings, the streets, do not lose their power as I walk around the city.

Being in a place like Florence, it is impossible not to be affected by the surroundings, by the grandeur and history of the architecture. Each street corner seems to have a story encased within the marble and brick. Yet, as I wander around Florence, or any other city, I begin my day with a list of places that I want to see, an architectural to-do list, as if ticking off the glories of the city like exhibits in a museum. However, my peregrinations never work out so efficiently and often I am distracted by the unexpected delight that does not appear in the guidebook. More often than not, I am drawn away from my agenda by the life of the city itself.

And yet Renaissance Florence was in some ways the first modern city and what remains, stretching across over 500 years, appears to be the forcing ground of the ideas and designs informing the cities we live in today. There are things that are so familiar: the way the streets are planned, the height of the houses, the mixture between the marketplaces, the public squares and the more private spaces. As seen in the towers and dramatic religious buildings, the design of the city is political; it is more than a place of habitation or exchange.

The city is also a happiness engine. From Plato’s notion of eudaimonia (flourishing) in The Republic, the pursuit of happiness has been one of the most important identities of the metropolis. The urban world magnifies our best aspects and it has been the task of successive generations to find the city form that releases these qualities rather than stifles, suffocates and destroys the human spirit. But how does this pursuit of happiness express itself in the relationship between ourselves and the buildings we construct? What is the relationship between the way we live and the places we inhabit?

The patron saint of the internet, seventh-century Spanish archbishop St Isidore of Seville, was the last scholar of the ancient world, the final flicker of the candle of learning before the Dark Ages descended. The youngest son of a distinguished family which included three other saints, he was at the forefront of the attempt to convert the conquering Visigoths to Christianity. He was also the author of the Etymologiae, a volume that aimed to preserve the sum of human knowledge before it was lost to barbarism. In this compendious encyclopedia his entry on the city is of particular note:

A city (civitas) is a multitude of people united by a bond of community, named for its ‘citizens’ (civis), that is, from the residents of the city. Now ‘Urbs’ is the name of the actual buildings, while civitas is not the stones, but the inhabitants.2

Even 1,300 years ago, Isidore recognised a division between the stones of the city and the people who lived among them. Yet the Spanish saint also suggested that there was a connection between the two, that civitas could be embedded into the very stones of the city, Urbs, and the properly planned place could stir the emotions and influence our behaviour. From the grid layout of Augustine Rome regulated by the Caesars, Medici Florence, Baron Haussman’s elegant boulevards that tore through the dilapidated streets of nineteenth-century Paris, to the re-imagining of Shanghai as the capital of the twenty-first century, architecture and political control have gone hand in hand.

But just as the judicious planning of urban space can enforce compliance and order, can architecture also liberate and nurture? Can a well-planned neighbourhood encourage a sense of community? The narrative of modern urban planning is the story of turning philosophy to stone. The twentieth-century planner was nothing if not ambitious: confident that he (for he is almost exclusively male) had found the technological panacea for the ills of society, convinced that building the city afresh would offer mankind a new start, accelerating people into the sublime realms of modernity: free from want, pain or unnecessary emotion.

The new city, he proposed, was rational, based upon the latest observations of the human condition, made solid into measured streetways and housing, and a considered balance between nature and civilization. The complexity of the ordinary street scene was to be ordered, while the exuberance of the dance of the street was criminalised and controlled out of existence. History shows us that there have been a lot more failures than successes.

Almost by accident, planners formed their own priesthood, wrapped up in ritual and arcane liturgy; every type of neighbourhood was anatomised and catalogued from ‘inner-ring suburbs’ to ‘central business districts’, ‘exurbs’, ‘sun-belt cities’, creating zones that were regulated into stasis, horrified by the seeming anarchy of an evolving, vibrant environment. The planners stopped talking to the people whose lives they were attempting to improve; they knew better; they spoke in an idiom that no longer connected; and as a result their expertise was no longer challenged.

This desire to know and control the city has its origins in fear and disgust. In 1853 the English art historian John Ruskin published the third volume of his work The Stones of Venice, a historical exploration of the Italian city at its moment of glory. He paralleled this Gothic masterpiece with his home city of Victorian London. Industrialisation, he argued, had turned the city into a factory and men into spiritless machines; only the revival of the robust, Gothic beauty of fourteenth-century Veneto could breathe life back into the soul of modern man. Ruskin’s cry was heard in Britain, the United States and across Europe; it transformed railway stations into cathedrals, sewage pumping stations into Byzantine fantasies, and factory workers’ houses into rural cottages.

Ruskin sourced his ideas from history, but this was not the only well of inspiration for urban thinkers. In the coming decades evolutionary theory, fantastical fiction, the desire to shock, the latest findings from newly forged sciences – psychology, sociology, psychoanalysis – would all be legitimate seedbeds for germinating ideas of the new city. However, as can be seen in the lives of three of the founding fathers of modern urban planning – Patrick Geddes, Ebeneezer Howard and Le Corbusier – the street was too often forgotten.

Just below the castle at the end of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh stands the Outlook Tower. Originally home to Short’s Observatory, Museum of Science and Art, the tower was purchased in 1892 by the then professor of botany at University College, Dundee, Patrick Geddes. Often considered the father of modern town planning, Geddes began life as a zoologist and as a young man was influenced by Darwin’s radical ideas of evolution, later lecturing on the life sciences at Edinburgh University. While he was there, he watched with dismay as the medieval parts of the old town were being demolished to make way for new buildings.

Knowing the importance of the environment and heredity as factors of Darwin’s theory of natural selection, Geddes began to campaign for the preservation of historic buildings, believing that the city was the form that best housed man in his most evolved state. To destroy the natural urban ecosystem, he argued, was to risk mutation and degeneration. Instead, Geddes offered a policy of ‘conservative surgery’ to the ailing city. Work should be done where buildings could be preserved and improved, and only the places past saving should be demolished.

In his attempt to save old Edinburgh he salvaged the Outlook Tower near to the castle and turned it into a museum that promoted his ideas of the philosophical science of cities. The building was split into six floors, each divided into topics, from bottom to top: the world, Europe, language, Scotland, Edinburgh, and finally the tower containing the camera obscura through which visitors could view the city and the countryside beyond. Thus he presented the story of the city, the ‘amphitheatre of social evolution’, within the wider context of history, region and geography. This idea was at the heart of his system of regional planning, which examined the relationship between place, history and region and the best conduct of the ideal citizen.

In his 1915 book, Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and the Study of Civics, Geddes set out his idea of the city as an instrument of evolution. He proposed that the development of the city was just one part of a wider network and that city planning therefore was not just the relationship between streets and public spaces, but also the city and the surrounding countryside, the drama of human history being as important as geography. This may have made sense when preserving old Edinburgh but Geddes also predicted the continued growth of cities. He was the first to develop the concept of ‘conurbations’, ever-expanding urban communities, estimating that the east coast of America could turn into one vast city stretching for 500 miles. This growth needed to be organised.

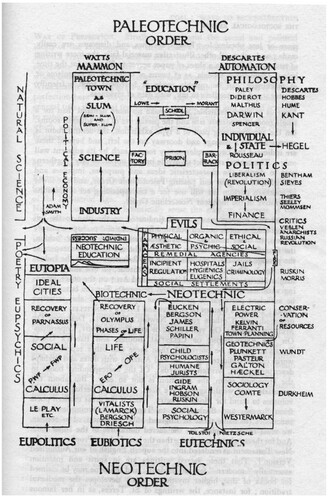

Geddes’s plans for the Outlook Tower, the orders of society divided and ordered

Geddes’s ideas were put to the test far from the ancient capital of Scotland in the Holy Lands in the aftermath of the First World War. In 1919 Geddes was asked by the newly appointed Zionist government to develop plans for a university, as well as new schemes for Jerusalem and the settlement of Tel Aviv in order to cope with the influx of arrivals. He began the process by walking around the site ‘at all times of the day and night … As he went to this hillock or that, examined a sukh, peered into a house, reverently touched a tree, Geddes had no set plan in his mind but he followed some inner vision.’3 Into the mix he also stirred childhood memories of reading the Bible. The result was a 36-page report, Jerusalem Actual and Possible. It is said by some that if the government had listened more to Geddes, and his understanding of ‘the harmonisation of social customs and religious ideas with the work of modern reconstruction’,4 the subsequent history of Palestine would have been very different.

His notions were inspired by the science of life, moulded by empirical observation and deductive intuition. Nevertheless, Geddes was a poor communicator of his own ideas, and was no architect who could give shape and form to his philosophy. Instead he found the perfect disciple in Lewis Mumford, an American writer who later became the most influential architecture critic of his generation. Mumford would turn Geddes’s looping, mental peregrinations into coherent and urgent theory, ensuring that regional planning was one of the dominant ideas of how a city should be.

As a leading member of the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA), Mumford transformed and popularised Geddes’s theories: allowing cities to grow unchecked was intolerable; people, industry and land were an integrated network that needed to be planned. Following the Great Depression, the RPAA was perfectly placed to give shape to the urban projects of Roosevelt’s New Deal, combining practical directives of urban planning and a positive social agenda that drove forward the rebuilding of America out of adversity. Many of the New Deal towns, constructed by schemes such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, saw whole communities emerging according to regional planning.

In turn, Mumford’s synthesis of Geddes’s regional planning found fertile ground back in Britain in the work of Sir Patrick Abercrombie, the man who campaigned in the 1930s for a greenbelt around London to halt the spread of the city. Abercrombie was also in charge of rebuilding London after the Blitz, developing his 1941 masterplan. This grand scheme for the rebirth of the city included the de-slumming of the old neighbourhoods, reducing density and breaking up communities into new towns on the outskirts of the city, and reconfiguring the city for the new age of the motor car.

The influence of Geddes was therefore felt around the globe long after his death. However, Mumford and Abercrombie’s philosophy of planning proposed a process without defining a model, and they needed to look beyond Geddes to find a shape for the new city. What they both found, in the work of a young English planner, was a design that did not look like any city previously seen; in fact, the new city was not a city at all, but a garden. They came to believe that the only way to preserve the city was to escape it altogether.

At the turn of the twentieth century Ebeneezer Howard was a stenographer at the Houses of Parliament in Westminster. Having spent his youth travelling through America, he was inspired by Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel, Looking Back, which imagined a young Bostonian, Julian West, waking up after 113 years’ sleep in ad 2000 and finding a perfect society in which everything was equally distributed.

Howard believed that this ideal could be founded in a new Garden City, planned from the ground up outside the industrial metropolis, but connected to the centre by the latest rail technology. The new city would have all the urban advantages but also benefit from the qualities of the countryside, as he wrote in Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898): ‘Human society and the beauty of nature are meant to be enjoyed together … Town and country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilisation.’5

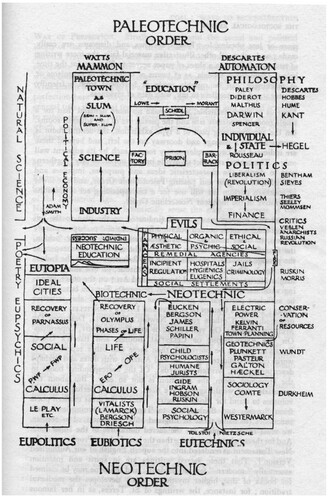

A detail from Howard’s Garden City

The future of the city was to be found by turning one’s back on the city and starting again, breaking new ground in the countryside. Reborn on such bare ground there was no need to take the past into consideration and the city could be planned from the first brick to the final form. In Howard’s vision the city was planned on a concentric grid with a library, town hall, museum, concert hall and hospital all gathered into the centre and set in parkland; this civic heart was ringed by the main shopping zone, designed as a glass arcade. Moving away from this were rings of housing, based around a 420-foot grand avenue, which also enclosed schools; and after that, centrifugal zones of factories, dairies and services. There was to be no smoke and every machine was to be driven by electricity. Needless to say, however, there was little discussion of life on the streets within the new Garden City; as Lewis Mumford would later write in his 1946 introduction to Garden Cities of Tomorrow, Howard was more interested in physical shapes than social processes.

Howard’s dream was turned into reality at Letchworth, Hertfordshire, 34 miles to the north of London, and has been recreated around the world ever since. Work began in 1903 at Letchworth, with the purchase of 16 square kilometres of land outside the town of Hitchen. The first thing to be built was a platform for the railway, and later a station was completed. Under the supervision of the great suburban architects Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin, who had become famous as the leading campaigners for the Arts and Crafts movement, the community grew, if not exactly following Howard’s exact concentric designs. It was said that only one tree was felled in the process of building.

The same philosophy was also tested in laboratories closer to London at Hampstead Garden Suburb, a scheme sponsored by the philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts, who wanted to develop a harmonious community with housing for all classes. In time, there were Gardenstädte in Germany, Cité-Jardins in France, Cuidad-Jardínes in Spain as well as other communities in Holland, Finland, India and Palestine. Forest Hill Gardens, in Queens, connected to Manhattan by the newly electrified Long Island Railroad, was the first Garden City in America.

In their own separate visions Mumford and Abercrombie gave a modern shape to Geddes’s philosophy of regional planning and Howard’s hopes for the Garden City. Mumford’s greatest achievement, in the end, was a book, The City in History, one of the most influential urban histories of the post-war world. Abercrombie saw his 1941 plan informing the rebuilding of London following the devastations of the Blitz. So it was that Mumford and Abercrombie influenced the lives of millions on both sides of the Atlantic.

Geddes and Howard both believed city building could deliver a new society. The Swiss architect Le Corbusier, on the other hand, first established an architectural theory and then went in search of the society to impose it upon. As a result his solution was very different in effect. While Ruskin, Geddes and Howard rallied against the horrors of the dense city, Le Corbusier desired to make it denser; as they sought to find refuge outside the city walls, Le Corbusier wanted to tear down the centres and build them up again; just as they wanted to put the city into the countryside, Le Corbusier decided that the parkland should come into the city. In addition, he did away with the street altogether. Le Corbusier thus hangs over twentieth-century architecture like a dark thundercloud.

Born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret in 1887, he changed his name to Le Corbusier in 1920 after an early career travelling, teaching and working on small-scale commissions. In 1923 all his ideas, observations and experiences thus far were summed up in Vers Une Architecture, a manifesto for modernist design: architecture was a machine, he declared, that was severely out of sync with society: ‘the primordial instinct of every human being is to assure himself of a shelter. The various classes of workers in society today no longer have dwellings adapted to their needs; neither the artisan nor the intellectual. It is a question of building which is at the root of social unrest of today: architecture or revolution.’6 Thus a revolution in design was the only thing that could halt the coming catastrophe.

Already, Le Corbusier was imagining a new type of city: a regulated metropolis of skyscrapers, in which the plan was at the centre of the work because ‘without a plan you have lack of order and wilfulness’.7 The idea thus became more important than the place, theory superseded life itself. The rightness of the plan ensured the evolution of a peaceful, happy society, whose voices were not encouraged. In addition, this revolution demanded men ‘without remorse’ who could see the project to its end without swaying to public opinion: ‘the design of cities are too important to be left to the citizens’.8

In 1925 Le Corbusier hoped to test his ideas with projections for the Plan Voisin that was the centrepiece exhibition in the Pavillion de l’Esprit Nouveau at the World Fair, Paris. His dreams demanded the levelling of most of the historic neighbourhoods of the French capital, north of the Seine – from the Marais to the Place Vendôme – and replacing them with long avenues, organised into a rigid grid system, filled with parkland and gardens. At the centre of each island was a vast tower block – the new machines for living. Thankfully the Plan Voisin was nothing more than an attempt to shock and was never intended to see the light of day; that did not mean, however, that Le Corbusier was not absolutely serious and his ideas further evolved into the concept of the Ville Radieuse, published in 1933.

Le Corbusier’s ‘City of Tomorrow’ was the supposed solution to the apparent problem of the street. The architect saw poetry in speed and so how could the massed chaos of the city be reordered to allow for maximum velocity? While Geddes saw the relationship between the past, landscape and present as integral to any city plan, Le Corbusier wanted to smash history, ‘burn our bridges and break with the past’.9 Where Howard desired the marriage of city and nature, Le Corbusier saw the city as the enemy of uncontrolled nature, a machine to defend man against the vagaries of the unpredictable and inhuman, including human nature itself.

Unfortunately Le Corbusier’s ideas did not fall on deaf ears but were embraced as a most exciting vision of the future. Le Corbusier himself was fêted as a prophet and was invited to build and design across the world. In addition his words were translated into every language and treated as gospel in most architectural schools and town-planning departments. He was the founding member of CIAM (Congrès International d’Architecture Moderne) which was started in 1928 and continued until 1959, bringing together the leading architects of the era and attempting to unify the whole discipline, offering one solution to every city’s problems. In particular, this solution was encased within a single text, the Athens Charter, that Le Corbusier compiled in 1943. The charter set in stone the laws of ‘the Functional City’.

The ideas could not have found more fertile ground; while Le Corbusier himself moved from the political right to the left during the interwar period, his philosophy was adopted by designers of all stripes. Thus it worked just as well in Soviet Russia, Fascist Italy, Vichy France, India in the aftermath of Independence, as well as Clement Atlee’s 1945 Labour Government that oversaw the beginning of the rebuilding of Britain following the Blitz. One of the unexpected outcomes of the war was the diaspora of numerous European designers to America, where CIAM’s ideas found an eager market, speculative developers saw the commercial advantages of the planned city, while civic authorities could accumulate huge powers by creating central planning departments. In effect, Le Corbusier offered a one-stop solution to the urban problem; the solution, however, involved complete destruction. It was a bitter pill, and we are still trying to get rid of the taste.

The irony can be seen in one of Le Corbusier’s earlier projects: Les Quartiers Modernes Frugès, on the outskirts of Bordeaux. In 1926, three years after the publication of Vers Une Architecture, Le Corbusier was invited by the eccentric industrialist Henri Frugès to design 150 new houses for his workers. Le Corbusier saw this as an opportunity to turn his theory of the modern ‘house-machine’ into reality and came up with a series of ideas. In the end only fifty of the houses were completed but each one conformed to the four basic designs he had projected. Each house had direct light, a roof garden, good ventilation and windows as well as a small frontage; inside, all was standardised and regulated. The designs expressed Le Corbusier’s passion for the mass-produced house; as he noted in his book, the workers should be forced into appreciating such uniform standards for it was ‘healthy (and morally so too) and beautiful in the same way that the working tools or instruments which accompany our existence are beautiful’.10

Except nobody told the workers who were meant to move into these new machines that their houses were tools and not places of domestic bliss. The first group of proud homeowners refused to come, disliking the look and the style. The houses were thereafter given to poorer workers. Almost immediately these new tenants started to adapt and personalise Le Corbusier’s designs: traditional wooden shutters were added to the plain façades as well as stone cladding; window boxes bursting with flowers blurred the clean, modernist lines; walls were knocked down and rearranged to make more space for internal rooms; sloping, tiled roofs replaced the flat concrete coverings that had started to leak; windows were replaced to let less light in, and keep the houses cooler.

This is a story that is often washed out from the history of architecture, but it should not be ignored. In time, the Le Corbusier Foundation blamed not the architecture but the sales methods that allowed a lower class of house buyer into the neighbourhood; meanwhile historians have used the example often as a way to vilify bourgeois ignorance. Le Corbusier himself said with some irony: ‘You know, it is life that is always right and the architect who’s wrong.’11 Unfortunately, so much of the history of urban planning has displayed this kind of disinterest in how people actually live; yet, as can be seen, life has a way of coming up from the streets and making itself felt. This was made clear in one of the most famous confrontations in the history of city planning.

If things had turned out differently, Robert Moses might, perhaps, have been celebrated as one of the greatest urban thinkers of the twentieth century. Until 1961, he was without question the leading urban planner in America, transforming New York to his will with a ferocious desire for power and an uncompromising architectural vision. Yet, in that year, he clashed with Jane Jacobs, a journalist and campaigner who was forced into action as her neighbourhood became under threat, over the very nature of the city itself.

Since his youth Moses had ambition to burn; educated at Yale, Oxford and with a PhD in politics from Columbia, he threw himself into civic government. Committed, modern, an idealist, his passion for the improvement of the future can even be found in his juvenile poetry:

To-Morrow!

But the morrow sure

To-Morrow!

The lashes slumber lure;

Ah! Shall we greet the dawning day,

Perchance in vain we longing say,

To-Morrow!12

It is a sentiment that he shared with almost every architect and urban planner of the period: a determination to corral the future, a dogmatic need to bring order to the unknown, a steely conviction of certainty in the face of all opposition. Moses’s first task was reorganising the systems of hiring and purchasing across New York’s City Hall departments. In the wake of this bureaucratic revolution, he was offered any job he wanted and plumped for the Department of Parks, hoping to implement a statewide scheme of green spaces. Between the 1920s and 1960s he more than doubled New York’s parkland, adding 658 playgrounds and 17 miles of beach. Yet his methods were overbearing from the start; as he told one Long Island farmer whose land infringed on his plans: ‘If we want your land, we can take it.’13

Moses’s schemes then became ever more grand, fuelled by F. D. Roosevelt’s New Deal dollars. He held twelve government offices at the same time, coordinating projects across the city. In the 1930s he turned his focus on how to get traffic in and out of the city; by 1936 he had already completed the Triborough Bridge system that linked Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx. The next year, the Marine Parkway-Gil Hodges Memorial Bridge opened, spanning Jamaica Bay between Brooklyn and Queens. A new network of expressways and parkways were devised and driven through the old neighbourhoods; roads were expanded and widened wherever congestion appeared. When he was not allowed to build a bridge between Brooklyn and Battery Park at the southern tip of the island, he was given permission to dig the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel.

At the end of the decade he was able to dream of a completely new city when he was put in charge of the 1939 World Fair, held at Flushing Meadow, and dedicated to the ‘world of tomorrow’. Moses co-opted General Motors to sponsor the Futurama display. It was a city, inevitably, that was created around the car: the city centre was replaced by vast highways lined by skyscrapers, embedded in parkland; suburbs were linked together by clean expressways. As the designer Norman Bel Geddes announced, ‘Speed is the cry of our era’; the ease and security of a life sealed within the carapace of the automobile, hurtling through the city without obstacles, the perfection of velocity replacing unpredictable human contact.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Moses continued his ambition to bring this city of the automobile to Manhattan, imposing his new order upon the chaos of the cityscape. In the 1940s and 1950s, Moses was the King of New York and began by focusing on housing in his autopolis, replacing old and out-of-date blocks with over 28,000 apartments set in high-rise towers. He laid plans for the Lincoln Center on the Upper West Side, as a cultural hotbed; he converted the road system of the metropolis, with Columbus Circle becoming the New York Colosseum. He also campaigned to bring the UN headquarters to the city, designed by Le Corbusier in 1950, resulting in one of the most iconic symbols of the modern city. By the mid-1950s, Moses could do no wrong; and the whole world not only agreed with his diagnosis of the city’s ills, but also his radical surgery. It seemed, for a brief moment, as if he had the answer to the long-standing question: how to build a happy city.

Jane Jacobs, despite her chunky bohemian jewellery and broad smile, was nobody’s fool. Born in 1916 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, she arrived in New York during the Depression and found clerical work while at night she honed her journalistic skills. Her work was picked up by Vogue and the Sunday Herald Tribune, where she gained a reputation for writing about the life of the city. She also signed up to study at Columbia University extension school, where she took a variety of courses, yet left before gaining a degree. During the war she worked at the Office of War Information, and it was during this time that she met her husband Robert H. Jacobs. In 1947 they moved into a flat above a convenience store at 555 Hudson Street, a run-down neighbourhood in Greenwich Village.

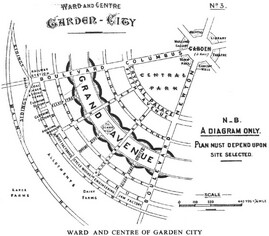

Jane Jacobs triumphant

Jacobs was a pioneering homemaker, moving to a part of the city that many had left, the old nineteenth-century houses subdivided and down at heel. Some of that clutter and chaos made its way into the Jacobs’s flat that friends remember as deeply untidy but with a huge amount of personality. It was here that Jacobs began to observe the Ballet of Hudson Street and came to understand the complex patterns of the neighbourhood that she later described in The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

By the late 1950s she was also working at Architectural Forum magazine, where she met William H. Whyte who shared her concerns about the dangers of city planning. While architects were in thrall to the grand projects, they both asked, where were the people? In a groundbreaking collection of essays, The Exploding Metropolis, both Whyte and Jacobs expanded on their ideas. In ‘Downtown is for People’ Jacobs reflected on the future city: ‘They will be spacious, park-like, and uncrowded. They will feature long green vistas. They will be stable and symmetrical and orderly. They will be clean, impressive and monumental. They will have all the attributes of a well-kept dignified cemetery.’14

From then on, the clash between Jacobs and Moses seemed inevitable. There was an early skirmish in the 1950s when Moses proposed driving a highway through Washington Square Park in order to ease congestion. Jacobs joined in with the campaign of energetic letter-writing, using her contacts to get high-profile support, including Whyte, the urban historian Lewis Mumford, who then wrote an influential column for the New Yorker, and even Eleanor Roosevelt. She brought her own children to the weekend protests on the square, providing perfect photo opportunities. On 25 June 1958 the New York Daily Mirror published a picture of Jacobs holding one end of a tied ribbon, symbol of a ‘reverse ribbon cutting’, signifying that Moses’s scheme had been delayed into oblivion in the face of determined opposition. Moses could only complain: ‘There is nobody against this, nobody, nobody, nobody but a bunch, a bunch of mothers.’15

Three years later Moses and Jacobs were at loggerheads once more when Moses proposed building the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LoMex) to ease congestion in the city. The only problem was that Jacobs’s home lay nearby and was thus under threat. Moses’s expressway connected the Hudson River Tunnel and the two East River bridges and would hand Lower Manhattan to the motor car. In consequence the ten-lane raised roadway would dispossess 2,200 families, 365 shops and 480 businesses as well as a number of historic buildings, breaking into some of the most renowned neighbourhoods: SoHo, the Bowery, Little Italy, China Town, the Lower East Side, as well as Greenwich Village.

It was a fair bargain, Moses thought, as he wrote that ‘the route of the proposed expressway passes through a deteriorating area with low property values due in considerable part to heavy traffic that now clogs the surface streets’.16 He had done this before: the Cross-Bronx Expressway relocated over 1,500 families yet was considered a revolutionary success. It was only later that commentators started to date the decline of the Bronx to this act of destruction.

Jacobs would have none of it; as she would later write, it was pure folly to think that Futurama was a real place: ‘Somehow, when the fair became part of the city, it did not work like the fair.’17 In addition, she refused to contemplate the break-up of her own neighbourhood. Jacobs threw herself into the campaign, becoming the chairperson of the Joint Committee to Stop the Lower Manhattan Expressway and intent upon putting an end to LoMex.

Yet perhaps her greatest weapon, which destroyed not just Moses’s project but his very reputation, was The Death and Life of Great American Cities, published in 1962. As the first line of the introduction makes clear:

This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding. It is also, and mostly, an attempt to introduce new principles of city planning and rebuilding, different and even opposite to those now taught in everything from schools of architecture and planning to Sunday supplements and women’s magazines … In short, I will be writing about how cities work in real life, because this is the only way to learn what principles of planning and what practices in rebuilding can promote social and economic vitality in cities, and what practices and principles will deaden these attributes.18

At the heart of this ‘real life’ was the street, the complex interweaving of people within the public spaces of the city. It was the street itself that was the principal object of study, and the metropolis’s organising force. The city needed to be reconstructed from the bottom up, not projected from the imagination of a grand wizard planner. This hopefulness may have seemed as vague as any previous vision of the city, another brand of utopianism about the self-organised neighbourhood, but it was powerful enough to force Moses to defend the LoMex project against a growing opposition. When Jacobs took the microphone at a public meeting in September 1968, the officials tried to turn off the sound. When Jacobs invited protesters onto the stage, the chairman called for the police to arrest her. Instead she led a procession out of the meeting, only to be met by a plain-clothes officer who escorted her to a patrol car.

Jacobs’s victory was sealed, while Moses hoped to keep the debate alive by writing ever more deranged memos and sending self-justifying packages to the Daily News. The project did not die, however; rather, in 1971, it dropped off the list of proposals eligible for federal inter-state funding and fell into a bureaucratic black hole. Moses lost his crown and his regal bearing; once the epitome of the master planner, America’s very own Baron Haussmann, he was soon held up to be the example of how not to build a city.

The stories of Geddes, Howard, Le Corbusier and Moses do not mean that all planning is bunk, and that all ‘top-down’ management for urban renewal is flawed. Neither should we see Jane Jacobs as a white knight or a small-time Nimby defending her patch against the forces of progress. Cities should be built for people, and architecture must concern itself with the many different ways of building communities, not breaking them apart. Urban planning often ignores the human element when in fact it needs to be at the centre of any project. We must be as careful to plan the spaces between buildings as the buildings themselves.

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs asked people to look again at the city, and enquired how we might improve what we have in hand rather than rip up the street and start again from scratch. She began her sermon with a plea to appreciate the life of the streets as the true signifier of the vitality of the metropolis. Secondly, the streets, parks and public spaces of the city, the places where people meet, were more important than traffic flow, efficiency savings and the creation of zones. Finally, all planning should be developed through an understanding of how people used spaces, what made them happy, and how they adapted these places for themselves.

Jacobs developed many of these lessons while working with and writing for William H. Whyte, the executive editor of Fortune magazine, who commissioned her first articles. In 1956 Whyte had written The Organisation Man, which had evolved out of a study of the rise of Corporate Man. In a devastating analysis Whyte suggested that the post-war generation had been encouraged into conformity, happy to exchange their own individuality to participate in the corporate dream, which not only dictated how they worked but also offered them the banal ideal of a secure life, the comforts of suburbia, the steady accumulation of unnecessary things. In conclusion, Whyte controversially claimed that the culture of Organisation Man, the surrender of self to the mythic corporation, was the very opposite of the rugged individualism that once built America.

Whyte’s fascination with how Organisation Man lived led him to investigate every aspect of corporate life, including the allures of suburbia. In a 1953 essay, ‘How the New Suburbia Socialises’, he used his own neighbourhood of Forest Park outside Chicago to show how the design of play areas, driveways and stoops affected interactions; how keeping the front lawn clean leads to strong ties to neighbours across the road rather than over the back-yard fence; why owning a house that was built in the early stages of the development can make you more popular. In time, however, he began to focus his attention away from the suburbs on to the city centre, which culminated in the 1958 series of articles edited by Whyte, The Exploding Metropolis, including Jane Jacobs’s first call to arms.

It would be almost a decade – the time in which Jacobs bested Moses – before Whyte put his ideas into practice. In the vacuum left by Moses’s decline, the New York Planning Commission hired Whyte to develop a new approach to thinking about the city. Whyte began by looking at previous best practice but was surprised to find no research on the efficacy of any of the most recent projects; he was stunned that there was ‘no person on the staff whose job it was to go out and check whether the places were being well used or not, and if not, why’.19 How could a city improve if it could not learn from its mistakes, or even find out if it had made any?

Whyte hired a group of sociology students from nearby Hunter College to start conducting some serious studies into how people actually used places; and so began ‘the street-life project’, probably the first time that a method was brought to bear on the ballet of the streets. As was to be expected, the results were revelatory. From this study of ‘the river of life of the city, the place where we come together, the pathway to the center’,20 Whyte built up his new idea of how the city really worked.

How do people walk down the street? How often do they bump into friends? Where do people stop to chat? Does bustle or a quiet space make a happy place? How much space should you leave as you pass someone? Who can you touch and what kinds of gesture are acceptable in public? Does a vendor get more business, or a busker more change, on a narrow street or a wide thoroughfare? Far more than the philosophical or aesthetic musings of visionaries, these were the real-life questions that can transform a city. Whyte produced his results in two books, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces in 1980 and City: Rediscovering the Centre in 1988.

In both books he saw the decline of the city as a reflection of the changing economic relationship between people; as our lives became increasingly mediated, we were less likely to interact, to bump into each other, and as a result the city was losing its most fertile function: the place where strangers meet. First studying the street, then making a series of observations on the social life of our public plazas, Whyte explored the ways in which these public spaces were used, how they developed their own ecology, what worked and what caused problems. Thus he set out some opening observations on how people used the street:

Pedestrians usually walk on the right. (Deranged people and oddballs are more likely to go left, against the flow.)

A large proportion of pedestrians are people in pairs or threesomes.

The most difficult to follow are pairs who walk uncertainly, veering from one side to another. They take two lanes to do the work of one.

Men walk faster than women.

Younger people walk somewhat faster than older people.

People in groups walk slower than people alone.

People carrying bags or suitcases walk about as fast as anyone else.

People who walk on a moderate upgrade walk about as fast as those on the level.

Pedestrians usually take the shortest cut.

Pedestrians form up in platoons at the lights and they will move in platoons for a block or more.

Pedestrians often function most efficiently at the peak of rush hour flows.21

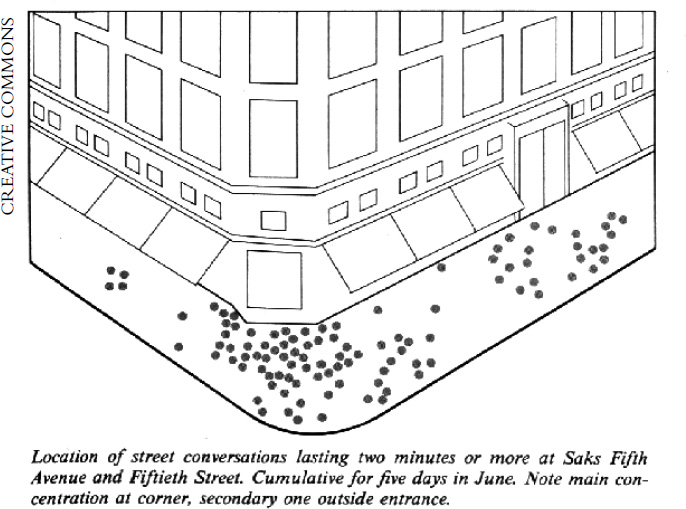

Whyte was surprised to note, watching the flow of human traffic outside Saks on Fifth Avenue, that most people stop to talk either on the street corner in the centre of the flow, or right outside the shop entrance. He also observed lunchtime in Seagram Plaza and how the spaces of the plaza were populated – men more likely to sit closer to the pathways and on benches while women prefer more secluded places; lovers rarely hide themselves; if there were movable chairs they tended to be dragged in all directions, each new occupant choosing to find their own site; particular groups were likely to rendezvous in the same places. In his most memorable phrase Whyte concluded: ‘What attracts people most is other people. Many urban spaces are being designed as though the opposite were true.’22

A diagram showing William Whyte’s study of crowds outside Saks Fifth Avenue

Whyte proved that people used the city in different ways than the experts had thought and often did the exact opposite of what the planners intended. Like the residents of Le Corbusier’s Quartiers Modernes in Bordeaux, people on the street don’t always behave as you want them to, however hard you try. Instead, Whyte highlighted the need to find a more open-ended, and engaged, planning policy that can make a real difference to how we use and feel about the city.

Since Jacobs’s epic battle with Moses and Whyte’s studies of everyday life on the city streets there have been a number of attempts to transform planning from an arrogant performance in which the architect knew what was best for the people, adhering to strict dogma as the necessary medicine for society’s irrational nature. Instead, many planners now recognise the value of a street-up approach, of designing for the way that people actually live rather than the way one might hope they behave.

One way of opening the potential for street-up communities is by doing away with planning restrictions altogether: let the people decide what their neighbourhoods look like. If you believe in the wisdom of crowds, the result is likely to be more complex and interesting than a community built from the imagination of one architect. In the district of Almere, on the outskirts of Amsterdam, such an experiment is underway. Holland is one of the most densely populated nations in Europe, so every inch of land needs to be managed and planned to cope with the demands of a growing population; yet in this unique neck of the woods it is still thought that allowing people to self-build their own homes may be the best way forward.

Almere itself was a planned city, started in the 1970s, designed to cope with the rapid expansion of the Dutch capital, Amsterdam. As communities were built out of a polder, land reclaimed from the watery marshes on all sides, the growth of the districts surprised even the developers and it was not until 1995 that the local government decided that Almere should be more than a series of dormitories with a scattering of centres, and become a centre of its own. Nothing if not ambitious, the authorities commissioned Rem Koolhaas to plan a brand-new city centre, to give the periphery its own cultural, business, retail and government focus. The results are impressive, including buildings by leading staritects such as Will Alsop, SANNA and Koolhaas’s very own OMA; but even more intriguing was that while this great project of creating a city out of nothing in as short a time as possible was underway, in another corner a completely different experiment was being conducted.

In 2005 local planner Jacqueline Tellinga initiated the Homeruskwartier, the self-build project, in the south-western Poort district. Covering over 100 hectares, the newly reclaimed land was divided into fifteen sub-districts to provide infrastructure, and then divided further into 720 plots. Each district was given a theme – low rise, live/work, sustainable development, shared and mixed accommodation – and the community was given a central zone to develop retail and office space. The initial costs of land were fixed at €375 per square metre, and some plots were bigger than others. The new owners were then given a passport as proof of ownership and left to their own devices; Tellinga hopes that ‘self-build leads to more socially cohesive cities whose inhabitants have a much stronger attachment to their surroundings’.23 Many cities are watching to see how Homeruskwartier grows and develops as a potential solution to the current housing crisis.

While it might be common sense to offer people more say in the way they build their own homes, do the same rules apply when thinking about public spaces? For so long our streets and public squares were barren places, to be traversed without hesitation, reminders of our anonymous smallness. We have lost touch with the city, as proven in a report conducted by Transport for London in 2006, which revealed that most people only understood London’s geography by the underground railway map, which presents a spacially distorted picture of the city; as a result one in twenty people exiting Leicester Square station on the Piccadilly Line had hopped on to the train at one of the two nearest stations, both of which are only 800 metres away. It is for this reason that when we think about cities we must concentrate not just on the design of buildings but the encouragement of life between the buildings.

This is exactly what the Danish architect Jan Gehl thinks. Gehl has long campaigned to redesign the city by putting the pedestrian first. Starting in his home city, Copenhagen, he was the driving force behind the Stroget Car-Free Zone, the longest pedestrian area in Europe, devised in the 1960s. Like Whyte, Gehl believes that the city can rediscover its original functions in the hypermobile world: the city as a place for discourse, for bumping into strangers and old friends, for the exchange of information and goods, for formal occasions like feasts and festivals as well as private pleasures. While new technology has allowed us to do many of these things remotely, they do not replace the human urge to be where other people are. As he writes: ‘Life in buildings and between buildings seems in nearly all situations to rank as more essential and more relevant than the spaces and buildings themselves.’24

Stroget – the joys of a car-free city centre

It started off as an experiment. At Christmas time it was customary to cut off the central street, Stroget, that ran through the middle of Copenhagen, for a couple of days. Yet in 1962 they extended the closure to engage public reaction. For some the plan could only lead to disaster, with complaints that ‘we are Danes, not Italians!’ and ‘no cars means no customers and no customers means no business’.25 Yet the opposite proved the truth. Slowly the street was renovated with new pavements and fountains; and the Danes became accustomed to street life: on sunny days cafés began to put tables out, performances were staged, shops changed their window displays to attract the ambling browser. The scheme was widened throughout Copenhagen until by 2000 there were already 100,000 square metres of the city centre pedestrianised. A bicycle scheme was devised with 2,000 bikes available for hire.

But what was the purpose of all this planning? If it was just a retail opportunity, it was a lot of effort for an open-air mall! Rather, the new street plan did not dictate how people should behave but offered them a theatre for their urban lives upon which the identity of the living streets emerged. The street was allowed to develop its own complexity, to be regulated but open, evolving.

This was not always so obvious. In the early years when musicians started to busk on Stroget they were moved along by the police, who presumed that their performance was a disturbance. Yet it soon became apparent that the streets were more than conduits of consumption but rather the ‘country’s largest public forum’.26 In a study in 1969 Gehl noted not only how people moved along the streets but where they stopped, what they looked at, what attracted their attention. While banks, offices and showrooms attracted the least interest, there was a marked slowing down in front of gallery windows, the cinema board, shop displays. The most arresting spectacle, however, were other people, from the man dressed in a Viking outfit advertising a sweater shop to jugglers and musicians: the various human activities that went on in the street space itself.

Yet where does this tipping point occur – when does the life of the street become the life of the city? Empty streets can be intimidating, and they do not become natural places of complex interaction without some effort. According to the Project for Public Spaces in New York, a group that was created by Fred Kent, who was involved with Whyte’s City Streets project in the 1960s and has worked on developing numerous public spaces, each space should have at least ten things to see to make it a vibrant place. As the PPS website explains, the power of ten can be scaled up in any way you like:

If your goal is to build a great city, it’s not enough to have a single use dominate a particular place – you need an array of activities for people. It’s not enough to have just one great place in a neighborhood – you need a number of them to create a truly lively community. It’s not enough to have one great neighborhood in a city – you need to provide people all over town with close-to-home opportunities to take pleasure in public life. And it’s not enough to have one liveable city or town in a region – you need a collection of interesting communities.’27

It is only the people on the street, however, who can tell whether a place achieves its purpose; a community will soon show whether it has embraced or adopted a new project. In the book How To Turn a Place Around, Kent tips the traditional relationship between architect and client on its head and shows that the community is the expert when it comes to the usage of a place. This has been taken to its logical conclusion with the increasingly popular practice of ‘crowd-sourced place-making’, which uses social media and the wisdom of the group to develop new places. It is indeed a radical alternative to the twentieth-century view of how to build a city.

Stroget in Copenhagen started out as an early example of a ‘pop-up’ community experiment – a temporary project. Often, the best ways to change the city are for only a short amount of time and on a small scale: improve the city block by block, allow people to own their own streets, make people the catalyst for change. The Better Block campaign was set up in the US in 2012 when a group of local activists and planners decided to do something for themselves and started to improve a single block in their neighbourhood. The location was an unloved stretch of asphalt which the group were able to transform into bike lanes, café-style tables and chairs, trees and pop-up businesses to encourage visitors. After the initial success, the group decided to up the challenge and have since conducted a number of 72-hour pop-up interventions where they turn a block around over a weekend. Thus in June 2012, their twenty-sixth project included an unloved warehouse district of Fort Lauderdale called FATVillage Art District. On one day, Professor Eric Dumbaugh and a group of students from Florida Atlantic set about to improve the neighbourhood, changing the 1950s industrial park into a temporary arts destination with murals, food trucks, a dog park and a farmers’ market.

Initiatives like Better Block are all part of a larger movement embraced by ‘tactical urbanism’. Here the emphasis is on incremental change from the bottom up, with a focus on five main goals:

A deliberate phased approach to instigating change

The offering of local solutions to local planning challenges

Short-term commitment and realistic expectations

Low risks, with a possibly high reward

The development of social capital between citizens and the building of organisational capacity between public-private institutions, non-profit and their constituents.28

Such tactical urbanism can be found in many places: Depave is a group from Portland, Oregon that tears up unwanted asphalt and returns the land to gardens. The Open Street Initiative has pedestrianised thoroughfares for the weekend to open up American cities to walkers and cyclists; the scheme now runs in over forty cities across the US. The mayor of New York has turned Times Square into a car-free plaza. The change in legislation on food trucks has allowed a new vibrant culinary culture in many US cities. Guerrilla gardening has turned forgotten corners of the city into blooming borders.

Making a city for the people makes a difference. After a century of architectural visionaries and their dreams of transforming human nature to the destructive nightmares of autopia that ripped up the old neighbourhoods in the name of efficiency and cleanliness, we have learnt that if we do not take account of the people who use them, it has every chance of failing. To rebuild the city, one must start from the street up and involve all those who live there. It is often where the best ideas come from.