On The High Line

I start at street level and the elevator raises me at a steady pace into the air. I begin to see the city from a new perspective as the pavement recedes below me. There is something thrilling about being able to look down on the city, no longer part of the throng, above the bustle and fug of the traffic, even if only from this height. Manhattan is a place that has been transformed by verticality; one feels it even going the small distance from the ground at West 14th Street up to the High Line, 25 feet above the Meatpacking District. As the elevator door opens, one leaves the underworld of the everyday city and enters another urban realm.

The High Line Park was first imagined in 1999 when two local residents, Joshua David and Robert Hammond, dreamed of transforming the derelict elevated railway line that ran through their neighbourhood in west-side Manhattan. By this time, the old industrial wasteland had turned into a wilderness of grasses and weeds, a blight on the landscape resulting in the local landlords calling for its destruction. The two set up Friends of the High Line despite Mayor Giuliani signing demolition papers for the rusting ruin. By 2002, the city had changed its mind; three years later, the line was handed over to City Hall and architects started to think about how to transform it into a living part of the community.

The landscape architects James Corner Field Operations became the lead team in devising the plans, with designs to turn a mile of the old rail line into a linear garden 25 feet above pavement level. The work was begun in April 2006 and continued until 9 June 2009 when the first section running along the Hudson River from Gansevoort Street to West 20th Street was opened to the public. Section Two, which runs from 20th Street through West Chelsea to 30th Street, was finished two years later in June 2011. Plans are in place to complete the final section of the line that will end near the Javits Center close by 34th Street. Since spring 2012 a public-arts programme has been underway, with a regular series of billboard projects as well as performances.

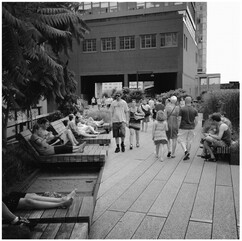

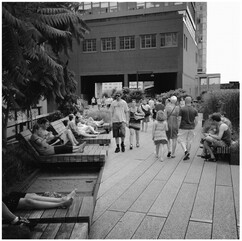

I am not alone; there is constant movement as the High Line has become one of the most popular sites for both visitors and New Yorkers. The rail line runs south to north and clusters of pedestrians are interweaving, following the flow in both directions. The pace is slower than on the street below; this is somewhere to saunter rather than sprint, a reminder that the city is not just one thing – a place of velocity, work, stress – but has many qualities that are too often forgotten or overlooked.

The city is vast enough to offer up its own image for every user. Thus for an economist it is a money machine; for a geographer, it is a social, topographical ecosystem; for an urban planner, it is a problem that needs to be rationalised; for a politician, an intermeshed weave of power; for an architect, it is the place where flesh meets stone; for an immigrant it is the hope of home and getting one foot on the ladder; for a banker it is a node within a vast network of global trading markets; for a free runner it is an assault course to be conquered. The city is too complicated for a solitary definition, and perhaps it is one of our greatest mistakes to think of it as a singular, measurable quality. Rather than looking for a single explanation, or a unique function, we must consider it as the interaction of different, albeit defined, parts.

Walking on the High Line

It is places like the High Line that allow us to think again about the city and how it can make us happy. Throughout history, critics have warned against the city’s destructive power. The atomising effect of urban life has been a charge levelled by naysayers since the time of the very first city. Out of the ruins of ancient Babylon, an excavated tablet reveals what is perhaps the first anti-urban rebuke:

The city dweller, though he be a prince, can never eat enough

He is despised and slandered in the talk of his own people

How is he to match his strength with him who takes the field?1

The city has long been considered the destroyer of men and, worse, their souls. Literature is littered with stories of the virtuous traveller brought low by its temptations. When Dante wrote of Hell, he had Renaissance Florence in mind. The romantic philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau saw the city not as a place of liberty but rather ‘a pit where almost the whole nation will lose its manners, its laws, its courage and its freedom’.2

Later, many would agree with Henry Ford, who believed that ‘we shall solve the city by leaving the city. Get the people into the countryside, get them into communities where a man knows his neighbours … there is nothing to do but abandon the course that gives rise to them’.3 Ford may have known something about selling cars but his view on the city, like his dictum on history, is bunk. Much is often made of what is lost as one enters the city; less is spoken of what is gained.

Sitting on a bench, taking a respite, one can see clearly how the many parts of the city come together and intermingle just as the flowers and shrubs bud and blossom in the well-tended beds that snake through the subtly designed concrete floor of the structure. The eye is drawn to many distractions, but perhaps most interesting of all is the other people who are also here. The city is a place where strangers come together, and at times like this it is possible to think that the metropolis is perhaps our greatest achievement.

Considering the genius of the metropolis is not a straightforward task. It is so easy to overlook the evidence in front of us. For centuries we have been taught that the city was bad for us, that it was the drain of our humanity, that it destroyed the old ways and traditions, split families and offered little in exchange but disorder, dirt and noise. It is this negative reading of the city that has affected policy, literature and architecture, sometimes to disastrous effect.

Today, we face a new set of challenges even more complex and pressing than ever before: climate change, unprecedented migration, the depletion of limited resources and a widely perceived decline in the civic values that hold our societies together. The consequences of a failure to acknowledge these problems are profound. Humanity stands at a tipping point between disaster and survival, and the city is the fulcrum upon which our future balances. In 2007 the UN announced that for the first time in human history 50 per cent of the world’s population lived in cities: 3,303,992,253, as compared to a rural population of 3,303,866,404. This number is rising at a rate of 180,000 every day; by 2050, it is projected that 75 per cent of the world’s population will live in cities.

We are now an urban species. In the developed world, we have become used to this reality, but elsewhere, in Africa, Asia, Latin America, these urban quakes are being felt for the first time. We are in the midst of the last great human migration in history: in the next five years it is predicted, for instance, that Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire, will grow 43.8 per cent; and Jinjiang in China by 25.9 per cent. By contrast London will only expand 0.7 per cent and Tokyo, currently the largest city in the world, 1 per cent. As I write, 150–200 million Chinese people are moving between the village and the city – the equivalent of twenty Londons or six Tokyos. The contemporary city is not what we have assumed and is about to change once again.

This book is a rallying call for the reclamation of the city from the grumbles of the sceptical and the stuck-in-the-mud naysayers. I believe that cities are good for us, and may just be the best means to ensure our survival. As I will show in the following chapters, we have often misread the city and this has informed the way we have designed, planned and policed it. Often the aspects of the urban personality that have most disconcerted us are actually the signals of the most vitality. As a result, the best parts of our home have been stifled and replaced by an idea of the city that has discouraged community, complexity and creativity.

By exploring the latest ideas, observations and innovations, I want to develop a new argument for urbanism, to rewrite the story of the past, and provide new hope for the future. The book will travel to a number of places around the globe to look at the many different faces of the city; it also delves into the past to search for continuities and characteristics that help us understand the contemporary. I shall show that the city has a personality that is often ignored: that the city is not a rational, ordered place but a complex space that has more in common with natural organisms such as beehives or ant colonies.

This observation has profound implications for how the city works. If the city is a complex place then it expresses certain characteristics that are commonly under-appreciated and have an impact on the ways we look at the political structure of the community. It also allows us to reassess the city as a built environment and as a creative place. Does the way we build the city have an influence on the way we behave? Can we create places that allow us to have good ideas? In particular, I will look at how building community and the question of trust are central to the idea of the happy city.

Yet, even standing on the High Line and looking along the streets that radiate outwards, one must acknowledge that the city is a place of extremes, inequality and injustice. It is a place that attracts the super-rich who want to consume the finest things the metropolis can offer, and the very poor who struggle to stay alive. In the coming decades the slums of the world are set to become the fastest-growing regions; these are often places of desperation, without resources, water and security as well as the precariousness of the informal economy. The metropolis is also the place on the front line of the climate-change debate. Cities take more than 2 per cent of the earth’s surface but use at least 80 per cent of all energy. If we cannot make our cities more sustainable, they could easily become our coffin rather than our ark.

Most importantly, as I watch the people walking up and down the High Line, sitting and chatting on benches, taking off their shoes and dipping their feet into the shallow pools, young toddlers giggling as they splash about until their clothes are soaked, I am reminded how cities can affect us, individually and as a group – and perhaps even make us better people.

It is time to think again about the city, before it is too late.