13

Wall Street and the Initial

Public Offering

When it’s time for your initial public offering, you—the successful entrepreneur who has made it through all stages of start-up funding and of getting your product to market—must now look to Wall Street. In this chapter we will look at how investment bankers are ranked for high-tech companies, their role in the IPO, what and who motivates them, and how rich they can get from an IPO. You will learn how to choose the best investment banker for your company.

The IPO is explained in detail, particularly how to time it, how to conform to securities laws, and how to price it, including how to apply some financial technology. We’ll also look at the question, “What should we do after the IPO?”

The chapter includes lessons from the IPO trenches, specifically from details about the actual Microsoft IPO. Microsoft faced all the key issues that a start-up’s CEO and CFO must deal with at IPO time.

New Issues and IPOs

“New issue” is the term applied to the first offering of stock of a new company, while IPO stands for “initial public offering.” They are two terms from the jargon used in the special investment world that high-tech industry observers talk about so often. This world is filled with glamour, glory, and a great deal of work for participants, who plan to make a ton of money when the IPO is completed.

This is the stage at which investment bankers enter the world of the start-up. The investment banker is in charge of the process that results in a single transaction that causes a flurry of activity in a start-up. The most significant change for the CEO and the start-up is being in the public limelight. Now the media are interested in the company and its leadership, and they request many time-consuming interviews, which takes up the time of the CEO and his or her staff.

The Wall Street security analysts enter the picture, taking up even more time for interviews than the media.

All this activity has a single objective: to attract and retain the institutional investors who will buy and hold the newly issued shares of the company. The analysts forecast the financial outcomes, the investors listen to their prognostications, place their bets, and wait for the company’s results.

Institutional investors are looking for new issues that will get them a higher return than they can get by trading stocks on one of the major stock exchanges: National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (NASDAQ), or the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The risk to investors in new issues is high, because the investment jungle is filled with hot speculators and rapidly moving stock prices. The number of shares available for purchase in a company already on the stock exchange is a tiny fraction compared to the number of shares that can be purchased in a new issue of a start-up, which means that the liquidity risk is much higher for an IPO investor. The business risk is also higher, and therefore a higher return is required to attract investors.

Forbes, BusinessWeek, Inc., other business magazines and web-based ’zines, and the Wall Street Journal—as well as a lot of newsletters for investors who specialize in IPOs—also cover the new issues market, and their articles make for instructive, sobering reading. In the long run, the IPO investing world is not a bed of roses and sure wealth creation. Annual reviews and regular IPO articles appear regularly in the media, including these headlines from our collection of classic clippings over the years:

Stellar performances of companies in

Venture’s Fast-Track 100 chart have Wall Street under a spell

When the going gets good, the good go public

But even in a hot IPO market, there are precautions entrepreneurs and investors must take.

Wall Street Goes Public

Last year, we told you investors were looking for proven management and a

history of solid performance. Well, they changed their minds.

From Harleys to Teddy Bears, everybody’s going public

The explosion of new stocks is astounding—and investors keep snapping them up.

Smart Money

IPOs: It can pay to have second thoughts first.

Hot, hot, plop. Investment bankers set records in the new-issue market. Investors

did not do as well.

Stacked Odds

Here’s a tip on playing the stocks in the steaming new-issue market boom.

But with the investment tip come important caveats.

Over the years we have found that the new-issues market takes on fads and fancies, just like other investment markets. There is an enduring interest in high-tech companies because of the belief that they have an above average chance of growing much more rapidly than other corporations. This means that the investors in such companies will become richer than if they had invested in low-tech companies. Is an Internet dot com a high-tech company? The wisdom of investment strategy is debated daily in the investment circles of Wall Street institutional investors, who range from endowment managers at universities to pension and mutual fund managers. IPOs are hot topics on the chat sites frequented by Internet traders looking for the lastest “buzz” on an upcoming public offering.

All this interest in an IPO puts the pricing of one share of stock into a new zone of financial estimation, scrutiny, techniques, and limits. Publicly traded stocks are compared with recent companies that went IPO, in order to get relative pricing comparisons. Techniques for placing a price on a share of the IPO company’s stock range from very crude to very sophisticated, and all this methodology receives the cold test of reality in the real world of stocks that are bought and sold every minute. This is a far cry from the much more private world of the start-up.

At times investors lose most of their money and become angry, believing they were misled by the company and its IPO helpers. The result is a lawsuit. Some companies associated with these legal actions are well known to media readers. Such lawsuits began to become all too familiar in the 1980s and continued in the 1990s in spite of legislation intended to curtail related abuses. For instance, in the August 10, 1987, issue of Business Monday, the San Jose Mercury News reported on fourteen Silicon Valley companies whose shareholders hit them with lawsuits alleging that investors were misled during stock offerings in the 1982–1983 bull stock market. Four of the defendants made settlements that totaled $50.3 million. In early 1990 several very successful high-tech darlings “hit the wall,” slowed their growth unexpectedly, and their stock prices crashed. Oracle and a half dozen others were quickly sued by lawyers specializing in such lawsuits. Most of these legal actions were against established companies, ones that had gone public long ago. But the message is clear: Do not try to get public money if bad news is just around the corner. It is dangerous to try to raise money just before bad news becomes public. The underlying, fundamental problem is the danger of investing in a “shooting star”—a company that gets going well, goes public, but has no staying power and sinks into mediocre financial performance shortly after IPO. It is no wonder that veterans of IPOs with whom we spoke talked a lot about “ juryproof prospectuses” and “D&O” (directors and officers) insurance.

Now let’s turn to the process of going public, starting with the investment bankers.

The Role of the Investment Banker

The investment banker will take the central leadership role at the time a company decides to do its first public offering of stock. It is the investment banker and his firm that will gather the lawyers, the analysts, and the many others who are needed to do the work for the IPO. The documents must comply with sophisticated securities laws. The behind-the-scenes workload is enormous and very time-consuming, requiring intense amounts of effort from a lot of people inside and outside the company. The process is complicated and must be done well. The investment banker is hired and paid a very large sum of money as a fee to ensure that the deal is done successfully by all the individuals involved. This job is akin to that of a shepherd herding a flock of sheep into the fold.

How Investment Bankers Are Organized. Whether you are interested in a large investment banker, like Goldman Sachs, or a specialist firm like Hambrecht & Quist, an examination of their organization demonstrates what the investment banker really does. The organization consists roughly of the following kinds of people:

- A pool of new business employees who call on private companies to screen them and discuss their interest in taking the company public. These specialized sales people (“new business” managers) are usually the CEO’s first contacts with the investment banking firm.

- The corporate finance staff of the investment banker. This group stands prepared to arrive at the start-up to do the work required after the CEO chooses their firm to do the IPO.

- The research staff, people who investigate the start-up once the firm is chosen. They give an independent opinion of the company’s quality and the risk and potential of good financial results over the next year or so.

- The syndication staff, which assembles a group of other Wall Street firms to insure (underwrite) the IPO so that the risk of the deal can be diversified. Each member signs up to share in supplying capital to back the deal. That group is called the “underwriters.”

- The sales department, which consists of stockbrokers who offer the new stock to investors, mainly institutional investors. These people are called “institutional sales people.”

- The traders are those who make a market for the stock by trading it, buying and selling shares in various quantities each minute of the day.

All together, the people mentioned above make up the organization called an investment banking firm. They are also known as stockbrokers and Wall Street firms.

There are many variations of this organizational structure, depending on the various securities that a firm decides to try to make a profit on. For instance, some investment bankers have their own venture capital business that invests along with the classic venture capitalists. Other firms have merger and acquisition departments or departments that make markets in stocks of much larger companies. The giants of Wall Street, such as Goldman Sachs, are full-service organizations that offer virtually any security-related service to investors. Internet investment bankers are the latest version.

Investment banking firms make money in various ways, including charging fees equal to a percentage of the money raised for an IPO. In a good year the owners of these firms make many millions of dollars per person and exceed even the league of riches that venture capitalists range in.

This is a service industry, and the competition is fierce and intense. There is much drama in the behind-the-scenes power plays and politics among Wall Street firms, venture capitalists, and members of the boards of directors of start-up companies. On the other hand, investment bankers try never to miss a chance to do an attractive deal and are therefore rarely confrontational. As one observer told us, “They are always trying to be very polite to everybody.”

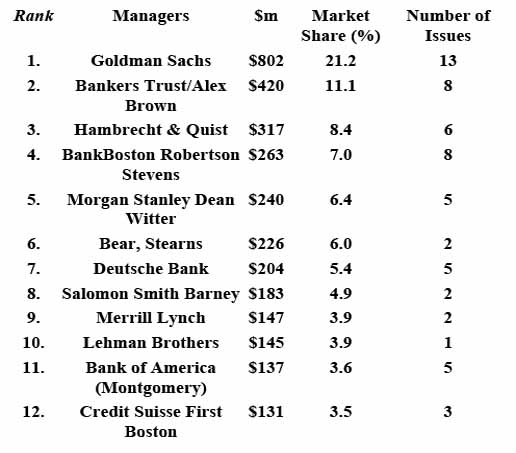

Differentiating Investment Banking Firms. Investment bankers are like venture capitalists: Each person has a distinctive character, and collectively these people make up a firm’s unique approach to the business. There are several distinctions that are important to you and your company. The most important is the firm’s track record with new issues, as distinct from its experience in raising capital for much larger, more mature companies. We have assembled a list of investment bankers based on those we found most often mentioned as participating in IPO stock offerings of high-tech companies. Table 13-1 lists those firms that have done IPO business in 1998. The top dozen are the giants in the field of high-tech start-up IPOs. The remainder are much smaller firms that often focus on limited markets in regional portions of the country. While smaller, these firms often do IPOs that perform well for investors in the post-IPO market. Research by Forbes magazine reports that frequently regional firms have done IPOs that outperformed those done by the bigger firms.

Table 13-1. Ranking of Investment Bankers for 1998 IPOs

Source: Venture Economics Information Services

Some distinctions are worth noting:

- Rising stock prices do not necessarily mean a good investment banker did the deal. How well an IPO did is a controversial issue. In the Internet era a lot of “dot com” stocks went IPO followed by an immediate huge spike upward in the price of the stock. At first that sounds like a good thing. But a big rise in the publicly traded stock price after the IPO was finished does not necessarily mean the offering was a success. If the rise is too large, the underwriter misjudged the market badly and cost the company millions of dollars. The value represented by the run-up in the stock price went to the pockets of the investment bankers’ favored investors at the expense of the start-up’s employees and private-round investors. Often such favored investors quickly sell the stock and reap a quick, usually large, windfall profit. This is the often criticized phenomena known as “flipping.” And if the stock price sinks back to near the offering price, many investors will be “under water,” holding stock worth a lot less than they paid for it.

- Smaller, regional firms should not be ruled out. They often have better track records than the larger high-tech specialists or the giants of Wall Street.

- Competition and the movement of professionals from one firm to another have caused changes in the leadership of the firms that do a lot of IPOs. In the 1970s, the most often mentioned IPO firms for high-tech companies consisted of the venerable Hambrecht & Quist, Alex Brown, Robertson Colman & Stephens, Montgomery, and L. F. Rothschild, Unterberg and Tobin. The arrival in the early 1980s of Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and other big names from Wall Street increased the competition for IPOs, and the rankings shifted considerably. And then during the 1990s consolidation set in. For instance, Bank of America bought Robertson Stevens (and through a merger with another bank ended up with Montgomery for a time). Bankers Trust bought Alex Brown (and then Deutsche Bank bought Bankers Trust). And in 1999, Chase Manhattan owned Hambrecht & Quist.

- By the time the year 2000 arrived, fresh competition in the form of Internet-centric investment bankers arose. Wit Capital was a successful Internet pioneer and Goldman Sachs later invested in them. Bill Hambrecht resigned from Hambrecht & Quist and formed W. R. Hambrecht & Co. to deliver a fresh way of eliminating IPO stock flipping. Sandy Robertson resigned from Robertson Stevens and later announced he would work with E*Trade to form an Internet-driven IPO firm E*OFFERING. The new arrivals promised companies doing IPOs lower costs without losing quality (and the Securities and Exchange Commission announced in 1999 an investigation into possible price fixing by traditional investment bankers). This fresh form of competition excited the investment community. The related controversy will be interesting to watch as the new century unfolds.

- Choosing the best research analyst to write about the IPO company is very important. Choosing an investment banker for a firm should be done carefully, using several criteria, only one of which is the rankings shown in Table 13-1. Veteran CEOs most often said their first and most important selection criterion was which investment banker had the best research analyst. Investment bankers will not do IPOs for direct competitors and thus CEOs had to often settle for their second choices in research analysts.

How Investment Bankers Make Money

A CEO can do a better job of negotiating and managing the investment bankers if he or she understands how the investment banking firm makes its money on taking a company public. The “fee” that is charged by the investment banking firm is actually not one fee, but a collection of fees granted to various members of the syndicate that team up to take a company public. The name or names on the front cover of the prospectus share the “management fee” for what is called “running the books.” This is more than a policeman or accountant type of duty. Those investment bankers have worked hard to get accepted as the lead underwriters and have agreed to be held responsible for the degree of success of the offering. They grant the rest of the syndicate the privilege of participating in sharing the fee.

The number-one position is granted to the firm whose name appears on the left side of the prospectus cover. Although the management fee often is shared equally by the two or three firms on the cover that choose to co-manage the deal, the left-hand position gains reputation and prestige for that firm, particularly for influencing the next IPO candidate company’s CEO with respect to how capable the firm is. The research community uses this positioning to create lists such as Table 13-1.

The underwriting fee, which typically is about 7 percent of the capital raised, is shared by the long list of firms that have put up a portion of their firm’s capital as a sort of guarantee to back the deal. The fee is split in proportion to the amount of capital the firm agrees to put up to back the deal. This is the least profitable of the investment banking activities, because it is used to cover expenses and is involved in stabilizing the price of the stock in its first days of very risky trading. Bankers regularly spend more than this fee covers. Academic research (such as that done by Roni Michaely of Cornell University’s Johnson Graduate School of Management) supports our findings.

The best way for the syndicate to make a great deal of money is to sell as much of the stock as possible. Aggression is extreme among the sales staffs of the firms. The goal is to outsell everyone, regardless of size, and to capture as much of the selling fee—which equals about 60 percent of the whole fee—as is possible. The bankers we interviewed told us that some pretty wild dealing takes place when shares allocated to one firm that cannot sell all of its shares are offered to other firms that have obtained orders for more than their allotments.

Green Shoe. Green Shoe is an overallotment option (to buy stock at a fixed price), which is given by the IPO company to the investment bankers doing the IPO. For instance, Sun Microsystems granted a thirty-day option to their investment bankers, co-led by Robertson Stephens & Company, to purchase up to 600,000 shares at the IPO price.

The over allotment shares are used to supply extra shares needed when an IPO is “hot” and (in oversimplified terms) more investors want shares than are available. This is part of a complex process, what is known as “making an orderly market for the stock,” and is an important responsibility of the lead underwriter.

Unlike the underwriting contract for the IPO shares, which obligates the underwriters to buy all the IPO shares at the IPO price, there is no obligation to the investment bankers to purchase any of these additional shares.

In effect, this appears to be a “bonus” to the underwriters, because if the after-market price rises to above the IPO price within thirty days, then the underwriters may purchase the extra shares at the lower IPO price, sell them to investors at the higher market price, and pocket the difference as a profit. For instance, the Sun shares were offered at $16 each. A 20 percent increase in thirty days to $19.25 would mean $1.95 million in additional profit for the underwriters, in addition to their fee of $3.92 million—a 50 percent boost! While that sounds like a windfall, research by Michaels and others shows it is most often used up (at no profit to the underwriter) as a cost of supporting the market for trading the stock after the IPO!

The Cost of Doing an IPO

Investment bankers first sign a company to an exclusive contract to do the IPO. The contract includes charging the company for certain of the expenses they incur in doing the deal, plus a percentage of the total capital raised. The CPA and legal expenses can easily be $500,000 for even a small $25 million offering. The “underwriters’ commission” or “investment banker’s fee” is in the vicinity of 6 percent to 12 percent (mostly 7 percent) of the total offering, including any capital sold in the IPO by selling shareholders.

These expenses are probably the most costly a start-up ever incurs because, under U.S. federal and state tax laws, none of them are tax-deductible. Thus, if the combined tax rate were 42 percent for a company, a 7 percent fee (including expenses) would be the equivalent of 12 percent pretax cost of IPO money!

The fee is negotiated between the company and the investment banking firm. It includes many subsets of fees, each composing a pool for many participants doing many tasks. They are broken down into two main groups: the fee of the investment banker, and all the other expenses. These are discussed in detail below.

Details of IPO Expenses. To start with, assume a start-up chooses to raise $10 million in a very small IPO, with all the capital going to the company and no selling shareholders. The costs for such an offering would be about 9 percent to 12 percent of the $10 million raised. The exact amount of expenses depends on three factors:

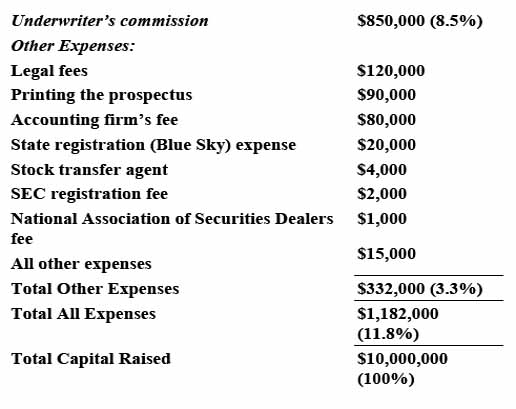

Table 13-2. The Cost of a $10 Million IPO

Source: Grant Thornton, Capital Markets Group

- The size of the deal. The larger deals have the lower percentage costs, but the absolute dollars of expenses get very substantial.

- The degree of work that lawyers and auditors must go through to clean up the books and records of the company and to convert them into a satisfactory prospectus.

- The amount of competition between the investment bankers desiring to do an IPO and degree of difficulty they anticipate in selling investors on buying the stock offered by the company.

Table 13-2 contains a list of expenses for a small new issue. It was compiled by an investment industry group that sought to issue a list of “typical costs” of going public. It is for a very small underwriting, $10 million.

IPO costs—as a percentage of the value of all the shares sold in the IPO—rise rapidly as the deal gets smaller. This occurs because the amount of work to raise $10 million is about the same as the amount of work to raise $25 million. The top investment bankers will strongly advise a start-up to raise as much as possible, at least in the region of $25 million. Of course, this also increases the absolute dollars of fee or “commission” for the investment banker and syndicate.

The percentage represented by “Other Expenses” shown in Table 13-2 is larger than in most of the actual IPOs that we have analyzed; this is largely because the IPOs we examined were mostly in the region of $25 million or more. It was not unusual for other expenses in the Internet dot com prospectuses we reviewed to total nearly $1 million or more, or about 2 percent of the capital raised. This percentage was more consistent than we anticipated. We had hypothesized that these expenses were rather fixed and not dependent on the amount of capital raised. But while our sample was small, our findings suggest that the participants—especially lawyers and accountants—may incur and bill their fees as some implicit percentage of the capital offered, just as the investment bankers do.

CEOs who have done IPOs recommend that a first-time CEO should set and adhere to a budget for each item on the Other Expenses list, using the same level of judgment as for any other service supplied to a company. The amount of cash expenses that could be saved by the company appears to be considerable, perhaps lowering the costs by as much as 20 percent.

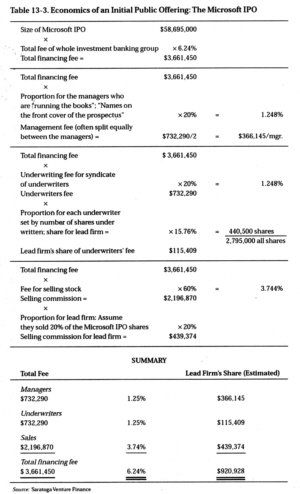

Microsoft IPO. Table 13-3 contains our estimates of the details of what made up the fee charged in one of the most famous IPOs in history, the Microsoft offering of March 13, 1986. IPOs since then, including those in the 1990s, show that very similar results prevail today. The Microsoft deal shows the magnitude of a large IPO offering. In terms of percentages it is therefore a good measure of the efficiency of the costs charged to a company going public. CEOs told us they would expect that a less famous company will probably incur somewhat greater expenses.

Table 13-3 uses the Microsoft IPO as a basis for estimating the approximate fees received by each member of the investment banking group. Because the actual details are private, the data in the table is an estimate of the approximate compensation earned by one of the co-lead bankers, Goldman Sachs. Goldman is considered by most to be number one in the world in doing equity deals of various sizes and types, and a firm of unequaled high character. The estimate is based on discussions with underwriters who were not in that deal but who compete with Goldman and others for IPOs. The exact numbers are less important than the reader’s appreciation for what motivates the investment banking group to behave as it does to earn the larger portion of the overall fee.

An analysis of the costs charged Microsoft reveal the following:

- The $58.7 million offering in this IPO is about double the size of many offerings of other highly successful companies that go public. This suggests that the efficiency of the cash cost per dollar raised by an IPO company will go up as the size of the deal rises (if one uses percentages to measure efficiency).

- The fee of 6.24 percent was consistent with the range of fees charged in similar-size offerings. The split of the Microsoft fee shown in Table 13-3 is estimated. Actual fees, splits, and amounts are uniquely negotiated by participants in each deal, depending on several factors, mainly size of the IPO capital to be raised. A fee closer to 7 percent or higher would be more typical for a $25 million IPO.

- Fees can be negotiated downward some distance below any so-called normal range. Some CEOs believe competition works in such negotiating situations. The CEO should try to set the target lower than 7 percent and get agreement to it before signing the underwriting contract. Some of the new Internet-centric investment bankers are charging less, in the range of 4 percent. In fact, some CEOs think it may be desirable to make the fee a primary determinant in choosing an investment banker.

- Not shown in Table 13-3 is a category called Other Expenses, which are in addition to the investment bankers’ fee. For Microsoft, the total Other Expenses (for CPA firm, lawyers, and special prospectus printer) were $541,000, or 0.92 percent of capital raised. These expenses are first revealed on the cover of the prospectus. They can be as high as 2% of the IPO.

- In the case of the Microsoft deal, we do not know exactly what the final fee was for each participant. But we believe we are pretty close in estimating that Goldman Sachs made at least $1 million on that offering. At the end of the day, everyone we spoke to said that they could appreciate how hard Goldman Sachs worked to earn its share of the fee.

- As for profit, it is much less than the calculated $3,661,450. Usually all of the portion called the underwriters’ fee is used to pay expenses of doing the deal, supporting the post-IPO trading in the stock, and the end is often a small loss on this portion of the deal. The selling commission requires paying for the costs of the personnel doing the work as well as their related overheads, as does the fee for running the books. The pretax bottom line for the deal was probably about $2 million, about half the gross fee of $3.7 million.

For more recent IPOs, CEOs can analyze the prospectuses of comparible IPOs and look at examples in the Saratoga Venture TablesTM at the end of this book.

The Role of Institutional Investors

The power brokers in the world of publicly traded securities are institutional investors. That is also true for the IPO deals. Wealthy individuals are somewhat of a factor. In the Internet era, “day traders” became a significant factor. (They are individuals who actively buy and sell IPO stocks, particularly speculative Internet stocks. They hold the investments for short periods of time, days or hours. They use “chat rooms” to exchange information about stock trading. They trade via their personal computers connected to discount brokerage firms communicating over the Internet.) However, the giant institutional investors who favor long-term investing remain dominant in IPO trading as in the other stocks traded over the NASDAQ and New York stock exchanges.

Investment bankers work hard to be the firm that gets to place the purchase orders for the institutions that buy shares in a new issue. Salespeople told us that the competition for sales and trading commissions is fierce. Investment bankers are eager for the buying customer to make a gain on the IPO stock. Several individuals said they believed this desire causes a strong bias against overpricing the opening trading price of the stock of a new issue. The necessary role of the investment banker is to delicately balance a nice increase in the price of the stock of the new issue on the one hand against the danger of being embarrassed because of an unexpectedly wild up and down ride in the stock’s price in the after market. In the pre-Internet era, too much run-up and the selling company would be upset because it had to sell too many shares to get the funds it wanted; too little rise in the price and the buying institutions would be upset because they want to count on a solid price increase. By 2000, it seemed everything had reversed: an IPO whose stock price did not triple or more was considered a dud!

Although the company is paying the fee and expenses, the investment bankers are not really working for the company doing the IPO. Over the years they have changed to become oriented more to very short-term transactions and less to long-term relationships. Many decades ago the investment banker sat on a company’s board forever and advised it on financing strategies. Today the economic forces at work cause these bankers to race from deal to deal, concerned about how to make as much money as possible for their customers—the institutional investors who have billions to invest every day. Although the bankers try to retain and nurture long-term relationships, one can really expect most investment bankers’ interest in a company to be limited to the next deal that they can do for it. The competition in their business is fierce, and they must be on their way, chasing the next deal as soon as the current one is done. They have a short attention span. Some venture capitalists compared such behavior to that of used-car salespeople and real estate brokers. We consider this remark unfair to the quality investment banker. Start-ups need strong Wall Street firms. This controversial situation presents additional problems in post-IPO relations with Wall Street, which we will discuss later in this chapter.

Together, the investment banker and the institutional investors are very powerful, and they can make a lot of money. Financial World magazine estimates that the ten most highly paid Wall Street professionals—investment bankers or institutional money managers—earned an average of $68.8 million per person in 1986, and in research about the 1990s showed many Wall Street partners earning in excess of $20 million per year. The IPO hot year of 1999 made many Wall Street people very rich. Such powerful, wealthy people represent a group that must be respected, one that must be incorporated into plans for a company’s capital formation.

Choosing an Investment Banker

Choosing an investment banker is exciting. The choice involves making selections that are not black and white, but the right choice is important. The consensus of start-up CEOs is that a good choice can make a large positive difference, while a poor choice can compromise a company’s future well-being.

While a company is still private, the CEO will receive a few phone calls from new business professionals of investment banking firms. They are checking to see whether the company should be on their list of target accounts.

Once a company is on an investment banker’s list, the CEO can expect to receive a lot of flattering attention, as will the members of its board of directors. The goal of the banker is to lock up the lead position, to become the designated manager who runs the books and thus earns a nice IPO fee. Because there is intense competition between firms for the handful of top IPOs each year, a CEO of a promising start-up has an excellent starting point from which to begin the selection process.

For the company ready for an IPO, any of the top twenty Wall Street firms could get the job done. But just getting the money in the bank is not enough. After the IPO, someone has to help make a good market for the stock. The degree of attention by Wall Street investors is a direct function of the amount and quality of research reports written about a company by the underwriting firm’s analysts. Furthermore, some firms have business reputations that a CEO would prefer to associate with or avoid. And board members, particularly venture capitalists, will also have various, often strong, opinions about which firm to choose.

Here is the advice of experienced high-tech CEOs on choosing an investment banking firm:

- Start by finding the best research analyst, one who understands the industry and technology. This is the person who will interpret a technology and its business applications for the salespeople pushing the stock. It is also the person who will go on the “road show” with the CEO, when the CEO stands up before institutional investors to tout the company’s good future. It is the analyst who will take precious time to write long reports about the company’s chances of success and its products. A company’s customers and employees will read those reports. Never pick an investment banker who lacks a top research analyst—one who is familiar with and respected as an analyst of the company’s technology and who favors that industry. A CEO can identify the top analysts easily by conferring with an experienced CFO of a large public company in the same industry.

- Pick a firm known for its integrity. This is very important because of the abuses and poor service that some technologically astute but financially naïve companies have had over the past years. Most well-known firms have retained high reputations, but some have grown tarnished over the past years. Presidents of some IPO companies have told us in strictest confidence of shockingly unethical misdeeds of the bankers who led their underwriting. The CEOs complained that their companies had suffered from the misuse of information and that post-IPO support dwindled to near zero. They also complained of questionable stock trades by bankers that they soon grew to mistrust. We concluded that the best check on investment bankers is to talk privately with the CEOs and CFOs who have done IPOs in bad times as well as good times. One can learn as much from the reasons a firm was not picked—or would not be picked for the next offering—as from the reasons it was chosen. Such work should be treated as seriously as a reference check of a key candidate for a vice presidency in the company.

- Look for managers who are businesslike, people whom it would be desirable to work and be associated with. As with picking an accounting or law firm, the CEO should be looking for character as well as competence. It is important to be methodical and thoughtful and to avoid being distracted by flattery. You want the best the company can attract. CEOs unfamiliar with the Wall Street crowd should start with the person who will manage the deal. It is important to look for characteristics that indicate the presence of a good business person, someone that can negotiate well on the founders’ behalf, someone who can be trusted. One good way to find this person is to attend the many meetings and investor conferences put on by investment bankers to expose the newest in high-tech companies to institutional investors. Dinners and lunches over a period of a year or so are also advised. This is an important decision and should not be made in haste.

- Compare statistics on IPO successes and failures. The post-IPO facts are important, as well as how many and how much capital was raised. The CEO should look for the bias of the banker; some have stronger retail and mutual fund customers than wholesale or institutional. The bankers themselves will each supply data, and the CEO can compare the facts presented by each firm. Forbes magazine and other publications also closely scrutinize IPO and investment banking firms’ performance.

- Be sure to check out how thoroughly the banker’s research analyst followed and wrote about the IPOs that the firm took public. Some CEOs told us of poor post-IPO service and were bitter about the “greediness” and “grab and run” attitudes of their bankers. CEOs with recent IPO experience can be helpful. The start-up CEO should talk to them about their experiences with (or without) the finalists on the list for investment banker. Note that analysts quite often move between firms. The analyst who did a good job for banker A may now work for banker B.

The importance of the analyst in selection of an investment banker is noted in this classic piece by Raymond Moran, then the director of research of Cowen and Company, a strong investment research and banking player in the personal-computer era (his message applies just as well today). Moran’s comment reflects our findings as we spoke with CEOs who went through the IPO process:

A research analyst with superior understanding of a client’s business and needs improves the ability to better position the company and communicate its long-term value in a highly credible manner.

And here is the suggestion of one of the grand veterans of high-tech IPOs, Sandy Robertson, founder of Robertson Stevens in San Francisco:

I recommend that CEOs looking for an IPO investment banker should seek a firm where everyone in the organization understands the company’s industry and business. This is especially important because an IPO is a chain of events—each critical to the success of the delicate IPO. Each person in the investment banking firm—corporate finance, research analyst, syndicate, sales, trading, and 144 stock ad-ministration—has to be successful when it is their time to carry the ball. To have a single expert in your high-tech industry just won’t get the job done. An IPO is too important to be left up to generalists or an individual. Everyone must be competent, experienced with high-tech IPOs, able to team up and do their part, and do it well for the IPO to be a success. That is what to look for when picking your investment banker.

And finally, here is the advice of Goldman Sachs to a CEO selecting an investment banker:

The selection of an investment banker involves both near-term and long-term criteria. For the purposes of executing a successful IPO, the investment bank should be actively involved in leading a significant number of equity offerings of high-quality technology companies. The investment bank should have a strong research presence in technology in general and in the company’s business in particular, and should provide active trading markets and significant distribution capabilities. Since the choice of an investment banker represents a commitment to a longer term relationship as well, the banker’s capabilities should also be able to accommodate a company’s anticipated growing and changing needs. The firm should project a global presence that provides its clients with access to capital markets and other opportunities throughout the world. The investment bank should have capabilities, experience, and dedicated resources in the areas of mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures, and strategic alliances. In addition, the bank should be able to provide advice and expertise in areas that will likely become important over time, such as real estate/headquarters financing and foreign exchange. Finally, but very important, a CEO should feel comfortable with the members of the prospective investment banking team and its firm’s long-standing commitment to technology and its clients.

The Initial Public Offering—The Holy Grail

A CEO will be better equipped to run a company while it is private if he or she understands how important the IPO event is to each participant in the IPO process. This perspective helps the CEO get the company tuned up and in good shape as it approaches the magic IPO date. This is an important part of planning, because the CEO may have to halt R&D expansion for a while or put on an extra heavy sales staff to boost revenues. The toughest decisions for the CEO will be to consider doing something that would be good in the short term for the IPO but could be bad for the success of the company three years or so later.

Employees. Psychological research reveals that every one of us wants to belong to a group, preferably a successful one. The IPO creates just that situation, as well as creating a pool of wealth that employees can share in. In reality, only a few people make a financial killing as an employee, except in unusual conditions such as with Yahoo and the early years of the Internet revolution. In fact, behavioral scientists note that, rather than actual wealth, the primary stimulant to people on payroll is the association of belonging to a company that is an observable winner.

These people want to believe in themselves, in their leaders, and in the whole company as winners. This success orientation was borne out by our talks with doctors, psychologists, and family counselors at hospitals and clinics in Silicon Valley.

When a company finally goes public, the CEO is fully exposed and must live in the spotlight, explaining disappointments as well as achievements to a vast audience that tends to be highly critical of the company and its leadership. “The press seem to be looking for the negative more than the good results,” lamented one CEO.

The management of employees goes a lot better when the stock price continues to rise; no one sells his or her stock then. But eventually the price will drop. Then the party comes to an end, and the reality of hard work returns. CEOs warned: “Too much IPO fever is like too much alcohol—it produces hangovers.” When Microsoft got to IPO, Bill Gates was concerned that having the company’s stock public would adversely distract employees. Similar comments have been heard from CEOs of Internet-era companies whose stock prices rocketed upward after the IPO. And remember: sky-high stock prices make stock options less attractive to prospective employees.

Finally, the CEO should keep in mind that missing an IPO window can be very demoralizing to employees. It is hard to avoid building up expectations, but keeping the IPO dreams farther away than nearer is better than having to deal with a tired crew that has just had its balloon pop.

Founders. To the original core team, the IPO means a lot—especially as the reality sinks in and the bank account begins to grow in riches. Lives change. Families change. People change.

Some told us that the reward is having recognition and fame at last. To others it was the arrival at a peer level with some role model in the high-tech world. Some people frankly said that it was pleasant to get revenge of sorts on the venture firms and business colleagues that turned them down or said that they would never succeed.

In cases we have observed firsthand, founders exhibited an enormous zeal to get to IPO time, some willing to pay almost any price—to their friends or their families. This appeared especially evident as the company came within a year or so of the first IPO date. Loyalties appeared to shift to the faction that favored an earlier IPO date. Pressure mounted to “get public while we can.” And we also detected a tendency for founders to believe that “after the IPO, things will get back to normal.”

Investors. Venture capitalists view the IPO as the date to get liquid. They told us that they work hard to get this far, enduring great risks, disappointments, and hard times. At last the day comes when they can begin to distribute shares to limited partners, rack up another high ROI in their portfolios, and seek out fresh money to manage, based on the latest successes.

The pressure on a VC to get his companies public is enormous. The VC does not run the operation of the start-ups; that must be left to much less experienced people, often with questionable track records. The possibility of a rising star turning into a fading star is always there, as history shows. Markets can turn against the start-up while it is still private. Microsoft or some other giant can make (and more than once has made) a surprise move that ruins the tiny company’s bright prospects.

Stock markets cannot be counted on. They move up and down, with little the CEO can do but watch. IPO stocks move in and out of fashion. When the new-issues market is dull or dead, the VC must risk more capital and invest to keep the private company alive, further draining funds intended for investment in other new enterprises. When the new-issues market is hot, the VC can sleep better at night because the windows of liquidation opportunity are wide open and unlikely to close in a day or so. Dave Anderson of venture capital firm Sutter Hill noted that the venture community is excited when IPO conditions are excellent, but that as soon as the stock market’s success flattens or turns down, the venture capital community gets much less euphoric. This happened after the great stock market crash on Wall Street on October 19, 1987. But by early February 1988 the first IPOs appeared with more rumored to be coming soon. The long-running IPO window that opened in 1990 was very good to start-ups, especially the Internet-intensive ones. Good days in the post-IPO stock market make for great prices per share in each IPO. More IPO successes mean more fresh money for VCs, and they too are happy. This positive trend was still going as 2000 arrived.

Because of these factors, the VC is not friendly to anyone who would hinder one of his private companies from going public. This includes founders who logically argue for waiting because the changes to the company plan might reduce its long-term potential.

The Process of Going Public

Vast numbers of books and articles have been written to educate the CEO on the process of going public. There are many other fine publications available from the top accounting firms and from the specialized printers of prospectuses. They are updated often, and most are free—just call one of their local offices for a copy or look them up on the Internet.

The value in these documents is that they serve as discussion pieces for planning sessions with the company’s staff, lawyers, and accountants prior to going public. The real education comes in actually doing an IPO. When searching for the right VP of finance, the CEO should look for someone who has some experience with an IPO.

Timing Is Everything. Nothing is so disheartening as missing the boat. “Get the IPO done when it can be done,” said several veteran board members of start-ups. Some famous misses include Internet pioneers Wired magazine and PointCast.

A close second to missing the IPO (for another year or so) is selling a new issue into a softening market, going out at $6 a share instead of $16—only to see the market rebound and the price explode up to $19 per share shortly thereafter.

Treasurers are specialists in timing successful financings, but few have yet to become CFOs of high-tech companies. Occasionally the original CFO is very experienced at picking the timing of the IPO, but that is not common, and the necessary judgment and wisdom is commonly defaulted to the VCs on the board of the company.

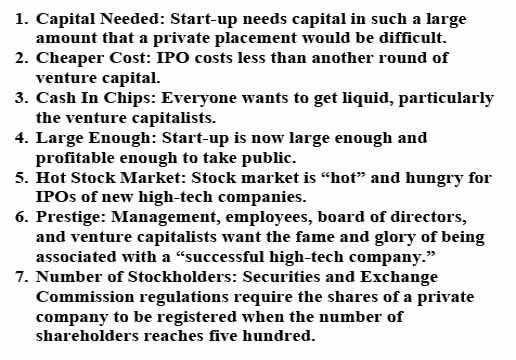

Investment bankers are skilled at sensing the opportunity for good timing of a new issue. They are eager to do deals and will sense even the tightest window available to squeeze the deal through. They do not want a slow-selling deal because that means they get stuck with “inventory,” stock that remains unsold because not enough buyers could be found on the day the IPO was sold. The underwriting firms can lose millions on a bad day if the stock market plunges and the new issue price follows the drop. Thus the banker does not want to overprice a deal and will instead underprice the stock a bit to cover the risk. The banker would prefer to sell into a rising stock market than into a flat or declining one. The banker will also know when the road show has produced enough oversubscription and will call it off and close the deal while it is hot. The short-term timing of an IPO should be left up to the lead investment banker. CEO thinking should be concentrated on getting into a financial condition that will give the company the flexibility and luxury of choosing the best date to go public. Financial flexibility is worth a lot. Table 13-4 lists six ranked reasons most often cited by the participants for going public. Another factor that sometimes plays a part is the number of stockholders. Securities and Exchange Commission regulations require the shares of a private company to be registered when the number of shareholders reaches five hundred. For example, Microsoft went public just as the number of shareholders was approaching five hundred.

Participants, Practices, and Principles. The group that is assembled to do the company’s IPO will work together very closely over a short, intense period of weeks. Their first focus will be to get the prospectus written, along with the related SEC registration documents. Here is what IPO veterans say about the participants in an IPO:

- Lawyers. There will be two law firms, one representing the company, the other the investment banker. They should send partners to do the work; no one else can make the necessary on-the-spot decisions that are needed to keep the work progressing quickly over the inevitable hurdles.

The job of the legal people is to keep their client from getting too exposed in the written documents. They will fight each other over trade-offs between who should be more or less exposed, the company or the underwriters. Both law firms are trying to write a document that fully complies with securities law, tells an exciting story about the company, and, in case of lawsuit, is easily defensible, or “juryproof.”

These high-tech-experienced lawyers are very expensive and scarce. Picking carefully can save expenses. The rules of thumb are: the farther from New York City the better; the farther from major cities the cheaper. Many smaller law firms familiar with high-tech start-ups are very experienced in public securities law. They are familiar with the start-up company and can do an excellent job. The investment banker’s counsel should be from a firm as close to the company’s location as possible and familiar with high-tech deals; the CEO should insist on this. The costs are likely to be lower because the hourly rate will be cheaper. Understanding of the business, industry, and technology will be there in depth.

- Accountants. The CPA firms will be trying to get the company’s books to balance for all of the past five years and to comply 100 percent with GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles). If the books have been kept up to date from the beginning, the accountants will be preparing the company for the IPO date and there should be no surprises. Using personal computer–based accounting systems for even the earliest stages of a start-up is also helpful in getting the books ready for public offering time without as much cleanup work as in the past. The partners of accounting firms are very aware of the many law suits that arose from the 1982–1983 IPO boom (unfortunately they continued as 2000 arrived), such as the precedent-setting Osborne Computer lawsuit against auditor Arthur Young by venture capitalists. Before the partner signs the formal CPA firm’s opinion that a company’s books are clean, it is the partner’s job to be sure that all the numbers have been checked many times over.

The accounting fee for the IPO is expensive, but it is not as large as it seems because the IPO-related work carries over to the annual audit, which uses much of the IPO accounting work. The IPO does, however, begin a new era of life for the company. The lower rates charged by the auditor for a fledgling start-up company no longer apply. The company will also be required to file SEC documents each year and will be charged additional auditing fees for the new SEC filings such as 10-Qs and 10-Ks.

- Investment Bankers. The lead investment bankers’ teams must include the top high-tech partner in at least a couple of the meetings, and a senior corporate finance veteran in all the sessions. The firms will be sure to have several very young people doing a lot of the detailed, grubby work, chasing down facts and figures, fetching the needed materials from the company’s accounting and other staffs. The bankers must make the prospectus sound at least interesting, if not a bit exciting, without increasing the risk of lawsuits. The partners will be extremely busy, typically simultaneously doing several other deals. One sign of this is that they constantly leave the work room to make phone calls during the drafting of your prospectus.

Most of all, the lead investment banker wants the SEC papers prepared and filed as soon as possible to avoid missing any window of opportunity to get the deal out and finished.

- Printers. There are specialist printing companies whose sole job is to print, in strictest confidence, 100-percent accurate securities documents such as prospectuses in large quantities, at any time of day or night, and distribute them in hours to virtually any location of the world.

These printers are very expensive as printers go, and charge for every edit and change. Their bills are usually far over the budget they submitted in their bid for the job. They will be able to document every charge to the penny, attributing every change to instructions from the prospectus team. The key to keeping the bills lower is to submit only the final—or nearly final—draft to the printer and to use all the electronic tools possible to cut down manual labor in these mostly union shops.

Table 13-4. Factors Triggering the Timing of Going Public

Source: Saratoga Venture Finance

Practices and Principles. The lead investor is the controller of the IPO working group, and is held responsible for adhering to the agreed-upon schedule.

The attorneys will be expected to compromise along the way and still produce a juryproof prospectus. The attorneys will try to eliminate any exaggerated claims made by the company’s marketing staff in its aggressive efforts to sell to customers and to the industry media.

The due diligence work is the double-checking done by the underwriters and the CPA firm. They will carefully check the facts claimed in the prospectus by the company. The investment banker has the freedom to challenge any figure or claim made.

“Get it done” is the slogan of the whole IPO team, especially as the second week of work proceeds. Life can get pretty agonizing as draft after draft follows change after change. To quote an investment banker who was one of the Microsoft IPO working group; “As usual, it was like the Bataan death march.”

Writing the Prospectus. The key to understanding a prospectus is to know that it is never used to sell the company’s stock. That is the job of the investment banker’s sales staff and is the reason the road show is so important.

The prospectus is a foundation document that marks a point in the life of the company. It is like a written business plan—its importance diminishes quickly as time passes.

As a result, things said by management to potential investors become more important than things written. At this point, practices that were acceptable for a private company must begin to be more disciplined. This applies particularly to statements by company officers about forecasts of sales or profits. Officers used to telling customers or employees about the company’s planned results must be trained to restrain themselves after the IPO date, because such projections have fueled lawsuits.

Pricing the Shares

When leading Alex Brown’s corporate finance group, Dick Franyo said, “I let the market tell us the price of each IPO.” He feels that his firm’s job is to fairly present the company to potential buyers and let them make up their minds on the price at which to sell the shares.

That is the reason the research analyst’s opinion is so important and the road show is taken so seriously. The road show is a trip organized by the investment banker. It takes the CEO and the company’s top management to the big money market cities. Over a week or more of whirlwind meetings, the CEO’s team endures countless breakfasts, lunches, and dinners; then, in the mornings and afternoons, it endures making presentations to selected institutional investors who have expressed interest in buying shares of the company.

The IPO share prices are determined by the market makers in much the same way that they set prices for the stocks of larger companies with longer track records. The most obvious difference is in the strong emphasis on the future—especially the growth in earnings and magnitude of return on invested capital of the new company, which is less than five years old. Special attention is given to the likelihood that the company will have excellent results over the next twelve months. In addition, the “uniqueness” of the company is examined closely. Managers are looked squarely in the eyes so that investors can decide whether the (usually) young management can continue to keep the company on the road to success.

Institutional salespeople from investment bankers are looking for “a good story”—their term for the company that has the best prospects for explosive success but that has not yet been discovered by the larger investment community. They try to find good stories, get their customers into the stock, and then turn their find over to the “herd,” hopefully to get the demand for the limited supply of stock to drive the price up. Weekly meetings with the research and corporate staffs of investment bankers focus on the details of the outlook for companies that the investment banker is close to, including the IPOs. The salespeople grill their counterparts to test the suggestions and investment opinions presented, then proceed to their phones and round up orders from clients around the globe, from Tokyo and Singapore to London and Paris, as well as throughout the United States.

While all of this activity is going on, the traders in the syndicate are testing the market with their colleagues in the firm. They must decide how to handle over-subscriptions if the stock gets hot and demand exceeds supply (that is the role for the extra shares waiting on standby in the form of the underwriter’s option). Similarly, they must be prepared to act if interest in the stock dwindles and the inventory of shares that the underwriters bought from the company is in danger of remaining unsold. If the expectations for preliminary demand for the stock are not met, the company may change its mind on the number of new shares to be offered, as well as on any amounts of shares to be sold by selling shareholders. This in turn will influence the price.

By the time the IPO is ready to go public, the whole focus is on setting the “strike price,” or the exact price at which shares will be sold to the investment banker (who will immediately sell them to waiting investors). The size of the order book and the ratio of orders to available stock will influence the final decision to increase or decrease the number of shares offered, or to change the intended price. In the end, the judgment of the investment banker will be relied upon to set the exact price. The agreed-upon price is then fixed, checks are exchanged, and the shares become the property of the underwriters. They, of course, hope to hold the shares for only a few minutes, selling the whole lot and the Green Shoe as quickly as possible.

Comparables. Investment bankers rely heavily upon comparables to price an IPO. They prefer to look for companies in the same or a related business and use those companies as a guide to pricing the new issue. The more unusual the company, the more the bankers run into difficulty using this technique. The start-up’s bankers will prepare such data for its deal and the CEO will be able to see and review the data with them. The CEO can also request that the investment banker prepare similar data on any company with which the CEO wants to compare his company.

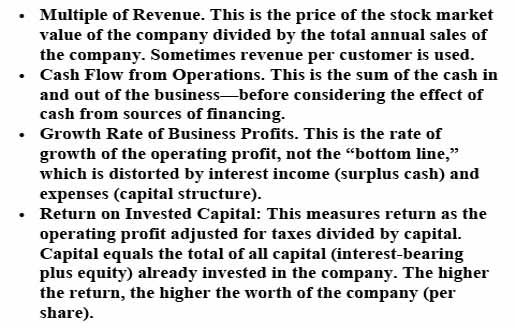

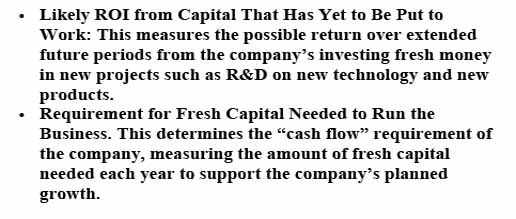

Ratios. Comparables still do not answer the question, “What numbers do the investors look at to make a pricing decision?” That is the subject of hot debate among investors worldwide, but it has been well researched over the past twenty-five years. The truth is that a few leaders set the prices and the herd follows. The numbers that the leaders look at most are future expectations (not history) of cash flow (not profits) and operating earnings tax adjusted (not net income), and return on invested capital (not earnings per share). The more important figures and ratios used are shown in Table 13-5. These primary factors are then converted into traditional financial statements in projected form and translated to price per share and multiples of revenue.

The CEO can forecast the numbers for his own company and apply the ratios used by research analysts, thereby reaching a decision on what the stock price should be. This will help in dissecting the reasoning the investment banker uses in setting the stock offering price. It will also help the CEO decide whether to hold off and wait for a better stock market or go now for a sure deal but at a lower price.

What Constitutes a Successful IPO?

Deciding what constitutes success in an IPO is worth thinking about, because the difference between a good and a bad IPO is worth millions in value to the company.

Potential Problems and Pitfalls. The central problem is picking the timing of the IPO. Waiting can be risky if business slips away from the company, but waiting can mean higher sales and greater value per share. There are also legal pitfalls linked to the post-IPO business performance of the company. The dangers of a lawsuit are quite real. In one classic case, founder Gene Amdahl personally had to pay $2.4 million in one lawsuit. Legal actions are daily pending on many more millions of dollars for companies whose stock prices plunged after their IPO.

Table 13-5. Quantitative Factors Used By Leaders to Set Stock Prices

Source: Saratoga Venture Finance

On the other hand, missing the window can be very costly. There is an old treasurers’ saying: Take your money while you can get it. There are companies that have been waiting for a good part of a decade because they missed their chance while an industry boom was on.

IPO investors are very picky about the companies in which they choose to invest. Investment bankers familiar with IPOs said this about what their people look for: “Comparables are less important. We look at the uniqueness of their concept, barriers to entry, size of their market, management quality, and the downside risks.”

The post-IPO price of the stock is of intense concern to everyone. The consensus is that the price per share should rise a lot, quickly; to most commentators that spells success. But if the rise is too sharp, it means the selling company has lost: It has sold more shares and its investors sold a larger percentage of the company than was necessary. A better solution would have been to sell at the price where the shares do not move in price after the IPO until an increase is due to a change in the perceived performance of the company’s future or to improved actual results that pleased investors.

It is very costly to pick an investment banker who does a poor job. This can and does happen when an IPO gets second-class attention or when the investment bankers are inept at IPOs. This is most likely in hot markets, when alternative deals are vying for the attention of overworked corporate finance staffs at the banks. The solution is for the CEO to manage and oversee the IPO, relying heavily on the CFO to ensure that the deal gets its “unfair share of attention.” Close scrutiny will also pressure sales staffs of the investment bankers to control information leaks better and to more carefully manage trading in the shares.

The company is put into a very dangerous situation when there are no Wall Street security analysts following and writing about the company after the IPO. This possibility is very real. Jerry Anderson, a cofounder and former chairman of the computer-aided engineering company Valid Logic of San Jose, California, lamented that one of his two lead bankers promised but never wrote more than a short introductory piece on Valid within the two years after the banking firm got its fee for the IPO. The Wall Street Journal wrote a lead article about that kind of problem in the August 12, 1987, issue of the newspaper. The headline read as follows:

Feeling Neglected

High-tech companies say Wall Street firms are abandoning them

after initial stock offerings,

some entrepreneurs say, bankers’ attention wanes

paying for the prestige factor

How to address and correct this post-IPO problem is discussed in the next section.

After the IPO

A successful conclusion to the IPO does not end when the IPO deal closes. It continues to the point at which the company is understood with reasonable accuracy by the investment community, and the company’s strategy, competitive advantage, and future prospects are being reasonably re-communicated by the Wall Street research community.

How do you achieve this desired result in a multitrillion-dollar global stock market that trades trillions of shares daily, has tens of thousands of stocks of companies to invest in—not to mention bonds, government bills, mortgages, real estate, gold, paintings, and so on? A fledgling company with less than two million shares sold to the public is not of much interest to most of the giant investors. Furthermore, each high-tech company must compete with other hot IPOs that are much more easily understood, such as consumer products companies that have huge upside potential in the large consumer markets. Getting regular attention is difficult and requires a lot of planning, strategy, and hard work, day after day after day.

The following sections reflect the advice of high-tech company CEOs and CFOs whom we have interviewed. We’re providing a summary of their comments, but their opinions about what to do were wide-ranging.

Managing Shareholder Relations. Shareholder management, or “investor relations,” is the process of controlling information released to the public while remaining in compliance with the law, so that expectations about the company’s future are kept in line with reality.

This process must be managed actively, because experience has shown that, left on their own, the investment community and general public media will gradually create distorted stories about a company, its products, its financial health, and its managerial competence. Such distortions increase the difficulty of managing the business, especially when large Fortune 500 customers begin to believe that the tiny company is in serious financial difficulty.

To do the job properly, the company must create a careful investor relations plan that is designed with the same thoroughness as a marketing plan for a product line. This requires skill and experience, such as that of a CFO who has done it before, a PR firm that offers such services, or an investor relations consultant who specializes in this area.

The company will need one person whose primary daily task is to disseminate and control the release of information to Wall Street research analysts and institutional investors. This person must be intimate with the policies and strategies of top management; in other words, he or she must know what is going on behind the closed doors of the CEO’s office. Surprises are unforgivable by Wall Street. Trust and discretion are two of the working skills of the investor relations manager.

Fire-fighting is a regular task of the investor relations manager. It occurs all too frequently: All companies hit a quarter when business suddenly is going to be shockingly below last week’s forecast; or the industry starts to sink and everyone starts layoffs; or a company’s newest, highly touted wonder product suddenly cannot be finished on schedule by its engineering department; or when a company’s latest product release turns out to be full of software bugs and customers are screaming murder!

The nature of investor relations is that of ferocious intensity. When trouble sets in, the CEO and his staff must drop all tasks until a tactical plan is created to deal with the latest rumors, good or bad, on Wall Street. The phones start ringing madly and will not stop until management provides satisfying answers to questions from the local business-news editors, irate investors, and worried research analysts.

Honesty and integrity are very important. Once burned, analysts are like elephants: They do not forget. “Burning an analyst” consists of surprising him or her, and a good surprise is as undesirable as a bad surprise. Any surprise prevents the analyst from being able to get the story—good or bad—out to favored institutional investors, complete with advice on what to do about it. Analysts are burned often, and therefore are experienced doubters, capable of detecting—from tone changes and intimations on the phone—any deliberate withholding of information about significant current or upcoming events—good or bad.

Consistency is important. Once a CEO starts to give out numbers, he must not stop during the embarrassing times. For instance, some companies openly talk about order backlog when it is strongly rising but stop when it gets bad. Good analysts have learned to read the situation exactly that way, and no one is fooled. Inconsistency makes the research analyst’s job more difficult. The analyst has built a spreadsheet model to forecast the financial statements of your company, using the parameters that the CEO has been giving out. If the CEO stops giving out the information, more uncertainty will be introduced into the analyst’s forecast; the CEO may then read of negative reports by the formerly favorable analyst, who is now explaining to his investing clientele why the new forecast and report on a company have changed so much.

Potential Problems and Pitfalls. Investor relations must be managed deliberately—as actively and deliberately as any other aspect of a business. Here are some of the problems the fledgling public company may face:

- Time Consumption. A CEO should count on the same percentage of time needed for managing investor relations as was required while the company was private. During Intel’s earliest years after its IPO, PR and marketing pioneer Regis McKenna got Intel’s top management committed to spending at least 10 percent and sometimes 20 percent of their time on each business trip with the media and Wall Street analysts.

- What Is Said. There is a large difference between what one says to insiders such as employees and venture capitalists and what one says to outsiders such as the top research analysts of the Wall Street firms. Some CEOs have found this hard to learn, particularly those who have been heads of divisions of large corporations and have become CEO of a company for the first time in their lives. Inability to adjust has cost several CEOs their jobs, according to some we spoke to who have experienced this problem firsthand.

- Control. Frustration of CEOs rises as they learn how independent the outside media reporters and research analysts are. It is difficult to adjust to the reality that those people can say whatever they want about a company—and do. Trying to “fix” and “correct” their opinions is often a time- and emotion-consuming effort that is wasted.

- Consistency. A company’s Wall Street positioning must be consistent with its business marketing positioning. Its customers will seek out and read the written Wall Street reports about its successes, failures, and expected future. Such reports must be considered an important part of a company’s marketing communications program. Wall Street will not regurgitate an exciting story about your company if that company’s marketing positioning statement is not defined crisply and in place. Analysts are very astute at poking holes in strategies, and uncovering “me-too” plans, and they are good at detecting lack of sustainable competitive advantage and distinctive competence.

A company can get special help from veterans of such investor relations activities by attending local chapter meetings of the National Investor Relations Institute. Here is a short list of the key principles that investor relations veteran Carol Abrahamson presented to members of the National Investor Relations Institute:

- Stocks are sold, not bought.

- Financial markets are influenced strongly by supply and demand factors.

- Information moves Wall Street as it builds expectations leading to assessment of the value of the stock of a company.

- Investors come in many types, some more appropriate for a company than others.

- Every company has unique investor relations needs that change over time.

- Every different type of investor has different information needs.

- Companies must compete fiercely to be noticed by investors.

Investor relations specialists can help a CEO build an investor relations program that is customized for a company’s special needs, whether it went public a year ago and is now frustrated at dwindling interest by Wall Street, is recently public, or has an IPO coming up in a few months and wants to plan ahead of time. The consultants feel their work will help a company reap appropriate benefits: consistent demand for its shares, fair valuing of its stock, and orderly trading of its shares.

Participants and the Role of the Securities Analyst. There is a collection of people who will team up regularly in the investor relations program for a company. Experts can get a company started quickly and methodically. In addition, there are special roles for each of the other participants:

- Lead Spokesperson. This is the person designated to answer directly the numerous daily phone calls from investors and others inquiring about the company’s stock and prospects. New IPO companies usually designate the CFO for this job. Others choose the CEO. It is a time-consuming assignment and is rarely delegated to the investor relations manager.

- Investor Relations Manager. This person must handle the administration and details of the newly public company. This includes taking the first calls from Wall Street analysts who will be requesting personal telephone interviews with the CEO and CFO, as well as visits to the company. This manager will be very influential in how well Wall Street regards the quality of communication with the investment community. It is a demanding job, one for people who are very good at being discreet, who are absolutely trustworthy, and who are skilled at articulating the company’s positioning statement and strategy.

- The CFO. The investor relations manager is usually responsible to the chief financial officer. This arrangement is a consequence of the need to comply with SEC regulations and the CFO’s familiarity with the financial community. The VP of marketing usually cooperates with the CFO, but focuses more time on communicating with customers than with investors. The CFO is considered a close second in importance to the CEO as far as communicating with research analysts is concerned. That responsibility can be daunting to a financial leader who has come up the ladder as a controller or auditor. This is one reason so many VCs hesitate to automatically grant CFO status to VPs of finance in companies about to go public. This is evidenced by the frequent number of times a start-up adds a CFO “heavy” shortly before it goes public.

- Lawyer. The chief counsel to the company, usually an outsider in a private law firm that helped the company go public, assists in several ways. He or she reviews and advises on 10-Qs and other SEC submissions read by analysts. This attorney counsels on press releases affecting investors, especially those involving responses to wild trading in the company’s stock, bad news such as layoffs, or unexpectedly bad financial results. The attorney provides practical advice on what to tell analysts in difficult circumstances, based on firsthand experience. In the end, however, the CEO, not the chief counsel, is responsible for what is said. The objective is to give the law firm an opportunity to review special news intended to be sent to Wall Street and the press, so that the company can benefit from a legal professional’s advice and avoid unnecessary legal mistakes in communications with analysts and reporters.

- Board Members. Especially important news is almost always previewed in confidence with those members of the board of directors who are active in the company. Quarterly earnings and bad news are most often discussed before release, typically on the phone or after the nearly final draft of the related press release is faxed in confidence to the secretary of the board member. This enables the CEO to keep everyone together, keeps communication consistent, and enables the CEO to benefit from the experience and judgment of board members, who often have been through similar situations in the past. The spate of shareholder suits in the twenty years up to 2000 demonstrates the importance of this practice.