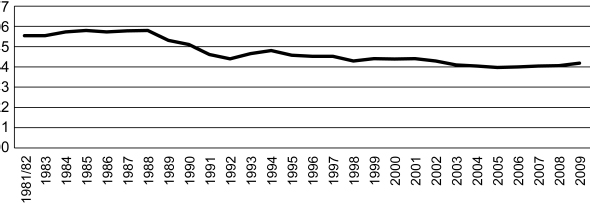

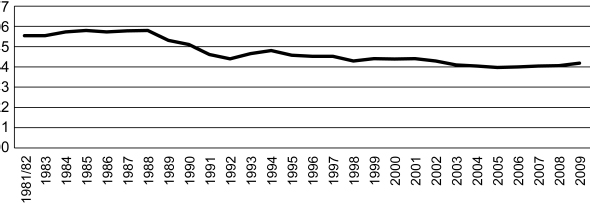

Figure 3.1Civil liberties in Africa, 1981–2009

Source: Based on author calculations in 48 African countries.

The Rule of Law and the Courts

The rule of law is today a major theme in the discourse on governance in African countries. Donors, intellectuals, and activists on the ground in African societies now highlight it as one of the key ingredients needed to promote social stability and economic development on the continent. Whereas the first three decades of Africa’s independence were characterized by the weakness, if not absence, of the rule of law in most countries, circumstances today are more favourable. African political systems are more ‘rule-governed’ than in the past, civil liberties have improved, and judicial and legal actors occupy more important positions in many societies. Yet the picture is not entirely positive. Executives are still the dominant players in African politics, and many of them operate with little regard for the legal boundaries on their authority. Judiciaries remain weak in terms of their capabilities and independence, and corruption continues to undermine the institutions charged with promoting the rule of law (Olivier de Sardan, this volume). All this serves as an important reminder that the rule of law still faces many challenges in sub-Saharan Africa.

In this chapter, I offer an overview of the rule of law and the courts in Africa. I begin with a brief discussion that reviews the concept of the rule of law and the importance assigned to it in contemporary conversations about governance and development. Thereafter, I review the historical experience with the rule of law in African countries since independence, dividing my discussion between the first three decades of independence and the period since the early 1990s, when many countries witnessed a substantial liberalization of their political systems. I conclude by considering the courts and the challenges that judiciaries face as the primary institutions tasked with promoting the rule of law.

Understanding the Rule of Law

What precisely is meant by the rule of law? In conventional usage, the term is associated with themes such as judicial independence, constitutionalism, rights protection, and social predictability and stability. All of these surely speak to the notion of the rule of law, but the concept deserves some elaboration beyond this, even if we must accept that there is no clear agreement on the precise meaning of the concept among scholars.

One way to begin thinking about the rule of law is that the concept refers to a situation where those in power exercise their authority in a manner that complies with the formal/legal rules of the political system (Maravall and Przeworski 2003: 1). Where the rule of law operates, governments act in accordance with the law and comply with the law (Diamond 1999: 90). Understood in this way, the rule of law is a property of political systems, varying across contexts, which can be observed in the extent to which power holders respect and are constrained by the extant legal regime (Sanchez-Cuenca 2003: 67). The notion of ‘constitutionalism’ obtains special relevance in this regard, as it attempts to capture the degree to which political life reflects and operates within established constitutional principles. The rule of law necessarily implies high levels of constitutionalism.

Beyond the notion of compliance with a legal order, some emphasize that the rule of law implies a legal system characterized by certain specific features: principles of natural justice, referring to basic fairness in legal processes, should operate; laws should be general, consistent, and prospective in nature; and the courts should be independent and accessible (World Bank n.d.; Sanchez-Cuenca 2003: 68; Raz 1977: 198–202). Others highlight that in practice, especially in Anglophone contexts, the rule of law has been associated with the protection of basic civil liberties (Donnelly 2006: 42). In this regard, the character of the legal system and even the substance of the law deserve attention when considering the extent to which the rule of law obtains in a given context.

As indicated above, independent judicial institutions represent a primary institutional foundation of the rule of law. Indeed, one can scarcely imagine the operation of the rule of law without an independent court system. Courts, for instance, provide a venue for the resolution of private disputes, which in the absence of formal systems of arbitration might degenerate into violence and disorder – signal features of the breakdown of law. Courts also help to identify and, potentially, sanction government behaviour that violates established rules of the political system. One key component of this is their role in protecting individuals, whether by ensuring that principles of natural justice are adhered to when governments attempt to deprive them of liberty or property, or simply by confirming the basic rights of individuals as laid out in legal documents (Donnelly 2006: 42–43).

Notably, the rule of law does not necessarily imply the existence of democracy, nor does it even demand a regime with high regard for human rights. The basic feature of the rule of law is a government that adheres to the formal rules of the political system, accepting that it cannot change those rules by fiat. While certain individual rights might be implied by the rule of law – access to the courts, due process, and so on – the actual substantive outcomes of legal proceedings may themselves appear at odds with human rights. Deprivations of property, limits on speech, and even state-sanctioned violence against individuals are all quite conceivable where the rule of law obtains.

When seeking to capture empirically the extent to which the rule of law operates in a given society, different bodies have developed indices that speak to many of the themes raised above. For example, Freedom House uses a ‘Rule of Law’ category as part of its assessment of civil liberties in different countries. The organization bases its evaluation of the rule of law on four questions (Freedom House 2008: 875):

Although these do not directly address the issue of government behaviour and compliance with the law, they do reference features of the legal system, such as equality before the law, and directly focus on the autonomy of judicial institutions.

The Bertelsmann Institute, a German organization that also undertakes regular assessments of governance conditions, also relies on four questions in its assessments of the rule of law (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2010):

As is clear, the Bertelsmann assessment focuses more on the workings of government and behaviour of its officials – a likely advance over Freedom House – but also considers the independence of the courts and substantive workings of the legal system in terms of civil liberties.

Yet this discussion of the concept necessarily begs a second question: why be concerned with the rule of law at all? The simple answer is that it matters. The extent to which societies are characterized by the rule of law has major consequences for their political and developmental fortunes. This point is fairly intuitive. Many scholars recognize that democracy requires the rule of law. As democracy hinges on the operation of specific rules, the system presupposes a rule-governed polity. The rule of law is also considered critical for economic development. The protection of property rights is especially important in this regard as this enables investment, which is critical for economic growth. Further, by protecting individuals through contract laws, the rule of law facilitates economic interchange. The predictability and order associated with the rule of law is more conducive to development than lawlessness and conflict (Haggard et al. 2008: 207–9).

Since 2000, research has substantially confirmed many of the assumptions about the positive effects of the rule of law. Kaufmann and Kraay (2002) found that higher scores on the World Bank rule of law measure contributed to higher levels of per capita income, but that the reverse relationship did not obtain. Other work by Feld and Voigt (2003) has indicated that higher levels of de facto judicial independence lead to increased gross domestic product (GDP) growth. Given these types of findings, it is little wonder that many bodies seeking to promote economic development, such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), are increasingly supporting programmes to enhance the rule of law in Africa and elsewhere (Carothers 1998).

The Rule of Law in Post-Colonial Africa

As those with even a perfunctory knowledge of post-colonial political life in Africa are surely aware, the rule of law did not flourish in the first three decades of independence. While there have been tangible advances in parts of Africa with respect to the rule of law since the end of the Cold War, major challenges remain.

The First Three Decades

Although constitutions, independent courts, and provisions for civil liberties were often established during the 1950s and 1960s when many African countries were achieving independence, in the aftermath, these institutions, and the rule of law itself, ceased to be primary elements of the governance situation in most countries. Their erosion occurred in the context of a general turn to authoritarianism and personal rule. The situation that emerged in most African countries was starkly at odds with the type of political system envisioned by the rule of law framework. Instead, the actual conduct of politics came to reflect the individual proclivities and personalities of those holding presidential power (Jackson and Rosberg 1982). Legal strictures rarely interfered with the exercise of power, and when they did, the law was changed to suit the needs of the power-holder. Constitutions, in this respect, had little relevance for politics.

Other institutions associated with the rule of law suffered similarly. The courts, for example, were emasculated and undermined in most contexts, leaving them to play a largely peripheral role in a political world dominated by the executive. In the early 1970s, for instance, the Hastings Banda regime in Malawi removed the authority of the common law courts over criminal matters and, in their place, revived a system of ‘traditional courts’. The latter came to be the primary venue where Banda tried political opponents and those suspected of disloyalty to his government. Notably, within the traditional courts defendants were denied rights to legal representation, the right to call witnesses, or the ability to appeal to the common law courts. In this context, the formal court system ceased to play any real function in protecting civil liberties or due process, much less checking the arbitrary rule of the executive.

Ghana affords other examples. The courts lost substantial authority shortly after independence when the government of Kwame Nkrumah established special courts to hear cases of treason and sedition. A roughly similar development took place under the Jerry Rawlings regime in the early 1980s, when the government created a system of ‘Public Tribunals’ (or ‘People’s Courts’)with the authority to hear cases regarding economic sabotage, smuggling, corruption, embezzlement, abuse of power, and subversion, and to render death sentences in those cases. The right to have decisions appealed or reviewed simply did not exist (Howard 1985: 341). In Uganda in the early 1970s, legal changes gave military tribunals the power to try civilians accused of offenses against the government (Widner 2001: 116).

In addition to actions that institutionally undermined (or replaced) the courts, judges themselves were the frequent targets of actions to subvert their independence. In the late 1960s, for instance, ruling party members stormed court offices in Lusaka, Zambia, which led ultimately to the resignation of the chief justice and several other judges. At later points, the government of Kenneth Kaunda enacted legislation that increased presidential control over court appointments. Legislation passed during Daniel arap Moi’s reign in Kenya stripped judges of security of tenure in 1988 and many judges were subjected to extra-legal transfers that undermined their autonomy (Mutua 2001). In Uganda, judges became one of the many targets of Idi Amin’s repressive rule. The chief justice himself was dragged from his chambers and never seen again, while the president of the Industrial Court was murdered. In the aftermath of his rule, conditions improved only marginally, as judges were unconstitutionally removed from office, arrested, and forced into exile (Widner 2001: 116).

Civil liberties also suffered markedly. Although sedition and preventative detention laws had been used by colonial authorities to suppress nationalist movements, these same laws were often kept on the books and in other cases, reintroduced and strengthened by post-independence governments. In Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah expanded the provisions for preventative detention in 1958, allowing the government to hold individuals without trial for five years. Uganda’s Milton Obote implemented similar legal changes, while Julius Nyerere’s regime in Tanzania and Jomo Kenyatta’s government in Kenya did the same in 1962 and 1966, respectively. In Malawi and Zambia similar detention laws were put to use against political opponents within the first few years on independence (see Harding and Hatchard 1993).

How can we understand this general decay in the rule of law in the post independence era? Part of the explanation lay in the general condition of governance in many African countries, and the dilemmas confronting post-independence leaders. On the one hand, leaders of nationalist movements frequently came to power on a wave of anti-colonial sentiment, but actually lacked solid legitimacy once in office. Combined with the weakness of Africa’s new states, this served to limit the authority of many executives, which in turn undermined their ability to accomplish their objectives and even left them vulnerable to challenges from rivals. Moreover, post-independence leaders typically had very lofty ambitions of fostering nation-building, development, and modernity. Unity came to be prized as a means to these ends, while competitive politics was seen as a distraction.

In this context, the dominant mode of political adaptation was the closing of political systems and the creation of new formulas of governance designed to consolidate and increase the power of the incumbent. Liberal politics and the rule of law were luxuries that a leader could ill afford lest his security and ambitions be undermined. The demands of security and unity were used to justify the suspension of habeas corpus laws, and the idea that a court system might protect those suspected of plotting the demise of the executive quickly became anathema.

Coupled with this, the courts and the legal system frequently encountered legitimacy problems in their own right. As Howard (1985: 324) wrote, ‘constitutionalism and the rule of law in Commonwealth Africa were originally imposed from above; hence, they may still be seen as both foreign and colonial institutions’. These legitimacy problems became more acute when the courts rendered judgments that were seen to conflict with local sentiments. The Zambian courts, and the white judges who sat on the bench, for instance, garnered considerable popular resentment in 1969 when they rendered a judgment against the state in favour of two Portuguese soldiers. Subsequent government badgering of the courts was seen less as an intrusion on judicial independence than an articulation of popular grievances. The Malawian courts also faced problems of popular support. Distrust of the courts heightened in the context of decisions in criminal cases in favour of accused individuals held to be guilty in the court of public opinion. In the early 1970s, President Banda decried acquittals of accused murderers based on ‘mere technicalities’ and moved forward with plans to reform the judicial system in a manner that allowed the ‘Malawian sense of justice’ to prevail, facilitating the introduction of ‘traditional courts’ (Williams 1978: 252–54).

Finally, it is worth noting that liberalism, the idea that the state should be limited and that individual rights should be protected, was hardly cultivated under colonial rule. In the imagery of bula matari, the colonial state was driven by a vocation of domination (Young 1994). Colonial subjects had few rights and were usually victimized by systems of indirect rule that utilized ‘traditional’ rulers as agents of control and extraction. Frequently such traditional rulers fused both executive and judicial functions, leaving individuals no effective legal redress against the state (Mamdani 1996: 53). On top of this, preventative detention laws were used by colonial authorities against those who challenged the colonial system and sedition laws were routinely used to control political protest and expression. Finally, colonial authorities themselves were quite unconstrained, encountering few limitations in the form of checks and balances and the separation of powers (Howard 1985: 325–27). Given this, constitutional orders creating a framework for the rule of law had very shallow roots in new African countries. To the contrary, especially in the case of preventative detention laws, the colonial system often left the legal tools to undermine the rule of law.

Under these circumstances, actors within legal and judicial systems who might have worked to promote and defend the rule of law came to play a relatively subservient role. Judges, for example, operating from positions of institutional weakness and personal insecurity, tended to defer to the interests of executives in their rulings (Howard 1985; VonDoepp 2009). Yet it is notable that in most contexts, the idea of the rule of law never died entirely. Judges and lawyers worked to preserve the narrow spheres of authority and competence granted to them. At times, these actors actually did take steps to challenge over-reaching executives in defence of constitutionalism and individual rights.

Widner’s account of the activities of Francis Nyalali, former chief justice of Tanzania, serves as testament to this. In 1977 Nyalali began serving as chief justice within Nyerere’s relatively ‘soft’ single-party system. During the 1980s, a number of incidents raised fears about the direction of the country. Judges became especially alarmed with the passage of an Economic Sabotage Act in 1983 that created a special economic crimes tribunal outside of the supervision of the judiciary. Beyond this, those accused under the act lacked rights of bail, legal representation and appeal. With the support of other judges, Nyalali appealed first to the president and then to the party central committee, voicing concerns about the law and the implications for the rule of law in the country. The law was later revised, removing its more draconian elements and reinstating the authority of the common law courts (Widner 2001: 145). At later points, Nyalali played an important role in pushing for the effective implementation of a bill of rights that had been passed in 1984 (ibid.: 192).

Judges in other parts of Africa also worked in limited ways to support the rule of law. While Zambian judges tended to support the executive (even endorsing the government’s exercising detention powers under state of emergency provisions) they also sometimes took an independent line. The Supreme Court in the 1980s acquitted individuals who had been found guilty of treason at the High Court. In two important cases, the courts ruled that the government had to have reasonable grounds to detain individuals, and that the court was competent to adjudicate such matters (VonDoepp 2009).

Lawyers were also active in these respects. In 1982, for example, the Ghana Bar Association decided to boycott the People’s Courts because of their violations of the basic principles of the rule of law. In Kenya, although lawyers were generally supportive of Moi’s authoritarian system, some were active in representing political opponents and civil society activists. As such activism increased in the mid- to late 1980s, lawyers themselves became the target of government. In 1986, two lawyers were detained for their alleged connection to a dissident group, while in 1987 the government detained a prominent Nairobi lawyer for filing a habeas corpus application on behalf of a dissident (Mutua 2001: 102).

These actors also played important roles in the liberalization processes that took place in much of Africa in the early 1990s. Lawyers were especially important players in the movement to reform Kenya’s political system, even taking leadership roles. In Malawi and Zambia, bar associations were part of broader civic organizations that worked for political liberalization. Individual lawyers also made use of court systems to support political reform, working for the release of multi-party advocates who had been imprisoned and challenging incumbents’ efforts to stall reform. Finally, lawyers in all three countries played important roles in drafting the constitutional revisions undertaken to liberalize political systems.

The same was true of judges. Francis Nyalali, while serving as Tanzania’s chief justice, served as the head of a presidential commission on political change and in that capacity was a primary advocate for the introduction of a multi-party system in the country (Widner 2001: 306). At a less visible level, judges in countries such as Malawi and Zambia rendered a number of decisions that were supportive of processes of political change. This included releasing detained multi-party advocates and challenging government actions that undermined the integrity of polling processes – developments that were critical to the democratization process (VonDoepp 2009).

The Rule of Law in the Multi-Party Era

With the transition to multi-party politics in many countries since the early 1990s, the prospects for the rule of law have improved considerably. Not only is the context more supportive of constitutionalism and rights protection, but there is also tangible evidence that clear advances have been registered. At the same time, very real challenges remain.

One development that has improved the environment for the rule of law is the elevated normative importance that is now assigned to ‘constitutionalism’ in many countries. Many of the political transitions of the early 1990s entailed not only the reintroduction of elections, but also efforts to re-establish constitutional governance. This often took the form of pressing for and sometimes negotiating constitutional changes, leading to the adoption of new constitutions in a number of countries. Since that time, questions of constitutional reform have remained on the forefront of national issues in countries such as Zambia and Kenya. As a partial reflection of this, discourse in African countries has increasingly focused on the concept of constitutionalism, both in terms of its abstract meaning and practical application. This is true at an intellectual level, as witnessed in the increased number of conferences taking place and publications emerging on the issue. It is also true at a popular level, where the question of constitutionalism is discussed in newspaper editorials and radio programmes. Indeed, a simple LexisNexis search by the author of the Internet source ‘Africa News’ provided nearly 2,000 references to ‘constitutionalism’ in African newspapers since 2001.

The international climate for the rule of law has improved as well. On the one hand, this is evident in the increased discourse devoted to rights and the rule of law at a global level. On the other hand, international institutions have prioritized civil liberties and the rule of law in their interactions with African governments. The US government Millennium Challenge Corporation, for example, considers the status of the rule of law and civil liberties when evaluating whether countries should receive funding from the Millennium Challenge Account. The World Bank also issues regular evaluations of countries’ progress with the rule of law as part of its assessments of governance. Given this prioritization of the rule of law, governments seeking to remain in good standing with international donors have had clear incentives to at least maintain the institutional edifice of the rule of law.

On top of this, political and economic conditions have elevated the importance of the legal system and the infrastructure for the rule of law. On the economic side, over the last 15 years, most African states have undertaken efforts to reduce the role of the state in the economy, opening up more room for private-sector activity. As a partial reflection of this, foreign investment in Africa has increased dramatically in the past decade (Lewis 2010: 198). This return of market economics and greater economic pluralism has significant implications for the rule of law. As scholars have argued, increasing socioeconomic complexity and diversity generate a greater need for mechanisms to ensure economic predictability, contract enforcement, and dispute resolution (Bill Chavez 2003: 420). This serves to boost the development of key elements of the rule of law – a court system, delimited rights to property, and codified law.

The development of more open political environments has also contributed to the rule of law. Open discussions of issues such as constitutionalism and judicial independence help to enhance normative support for the rule of law. Moreover, the density and number of civil society organizations have increased dramatically in many African countries over the past two decades. These organizations have proven especially important in countries such as Malawi and Zambia, where broad-based social movements challenged and thwarted executives who sought to amend constitutions to increase or enhance their power. Finally, competitive politics in the form of electoral contestation has increased the importance of the legal and judicial institutions, which are often called upon to resolve disputes about electoral processes and outcomes. To be sure, robust electoral competition, coupled with substantial judicial involvement in politics, can sometimes put judicial institutions in the firing line of incumbents seeking to maintain power (VonDoepp 2009). Nonetheless, open and competitive politics has increased the relevance of judicial institutions in national political life.

The improved status of the rule of law in Africa can be witnessed in a number of different respects. Consider the change over the last three decades in terms of sub-Saharan Africa’s civil liberties scores from Freedom House, as displayed in Figure 3.1 (lower scores indicate better conditions with respect to civil liberties). These scores include a specific measure for the rule of law as described above, as well as a number of other measures focusing on the status of civil liberties in countries. As is evident, substantial improvements were realized in the early 1990s, while gradual improvements have continued throughout the last decade.

Figure 3.1Civil liberties in Africa, 1981–2009

Source: Based on author calculations in 48 African countries.

Moreover, as Posner and Young (2007) have ably argued and demonstrated, the formal rules of the game matter today much more than they did 20 or 30 years ago. While African leaders used to leave office through coup, violent overthrow, or assassination, over 1990–2005 incumbents have most often left office through constitutional means, either through electoral defeat or as a result of the imposition of term limits. In other words, leaders have increasingly demonstrated respect for constitutions and constitutional processes when making decisions about whether – and how – to leave office (Lindberg, this volume). Notably, virtually all of those who attempted to change the rules of the game – for example by removing or extending term limits – did so through constitutional processes, and all three who failed acquiesced to the final outcome and left power (Posner and Young 2007).

Finally, lawyers and judges are playing increasingly visible roles in African countries, which is in itself a reflection of the increasing significance of formal rules in political life. It also demonstrates the increasingly plural and competitive nature of politics, which engenders the need for mechanisms of dispute resolution. Courts especially have been charged with rendering decisions with major consequences for national life. In Malawi and Zambia, for instance, courts have been centrally involved in electoral politics, determining issues such as whether certain candidates can legally stand for office, whether electoral processes were conducted fairly, and whether national election results should be upheld. In both countries courts have also rendered judgments regarding freedom of expression and the right of citizens to demonstrate, and have adjudicated disputes about the proper exercise of executive authority.

Moreover, in dramatic contrast with previous periods, court decisions in these kinds of cases have frequently, if inconsistently, indicated that judges are willing to uphold the rule of law even when it conflicts with the executive’s interests. For instance, court decisions in Malawi and Zambia that halted executive measures designed to undermine protests and demonstrations played an important role in preventing the amendment of the constitution to allow the sitting president to stand for a third term (VonDoepp 2005). At times, Zambian and Malawian courts have also extended protection to journalists charged by the government with infractions related to their reporting of political events. So while courts have also rendered a number of decisions that have supported executives, sometimes in ways that would appear deleterious for checks and balances and a liberal political dispensation, the key point is that they can no longer be considered mere lapdogs of government (VonDoepp 2009).

All of this said, there remain substantial challenges for the rule of law in Africa. Although the formal rules matter in ways that they did not in previous years, personalist and neopatrimonial tendencies still operate in political life. One extension of this is that executives continue to place a very high premium on holding and maintaining power. This can place pressure on the legal and constitutional frameworks designed to structure political life, as rulers bend, circumvent, and change rules in the exercise and pursuit of power. As indicated above, many presidents have attempted to alter rules of the game to allow them to stand for third presidential terms. In so doing, they have sometimes stretched the limits or openly violated the rule of law. In Niger, the effort by former president Mamadou Tandja to extend his time in office led to the actual suspension of the constitution, which itself precipitated his extra-constitutional removal from office by the military in the months that followed.

The volatile and tense character of political life can also lead presidents to take steps that place strains on the rule of law. During his first term in office, Malawian president Bingu Mutharika was forced to govern in a situation where the legislature was controlled by his opponents. While Mutharika faced persistent gridlock and paralysis with respect to policy initiatives and appointments, he was also forced for two years to deal with a persistent impeachment threat brought by his opponents in the legislature. This led to measures such as the closing of parliament in 2008 in a manner that had dubious legal backing. Moreover, fearing that his opponents had supporters in the state apparatus, and facing a legislature that was unwilling to approve new appointments to government posts, the president attempted to make a number of personnel changes that violated the legal procedures for doing so. In another instance, the government defied a court order requiring it to restore the security and other entitlements of the vice-president (the president’s opponent) after these had been withdrawn (Kanyongolo 2006).

It also needs to be remembered that in their routine dealings with the state, citizens in many African countries continue to experience predation, arbitrary decisions, and abuse, with little recourse to legal instruments for redress. As Englebert (2009) has so effectively described it, those in state positions, such as local police officers, agricultural extension workers, market supervisors, etc.; have the power of ‘legal command’. This allows them to exercise power over citizens and prey on them for resources, and so state authorities routinely violate the legal mandates of their office during face-to-face interactions with citizens – a key sign of weakness in the rule of law. A survey conducted by Transparency International in Kenya in 2004 indicated that 78 per cent of citizens were asked to pay bribes when engaging with law enforcement and regulatory officials. On average, urban Kenyans reported paying 16 bribes per month. A similar study undertaken in Zambia indicated that nearly 60 per cent of Zambians were asked for a bribe in 2009. In almost all cases, refusal to pay a bribe leads to the denial of the service.

One additional challenge is that very few citizens have means of legal redress when they suffer inappropriate treatment at the hands of state authorities. As a number of studies have documented, for most poor citizens, legal systems are inaccessible owing to the skills and resources needed to make use of them. On top of this, lower-level courts are often perceived to be corrupt and woefully inefficient, creating further disincentives for average citizens to attempt to work through the legal system. This problem takes on special relevance with respect to women, who face unique barriers to the realization of their constitutional rights (see Mama, this volume). These barriers include the need to negotiate customary law in matters of inheritance and divorce and social norms that work against women’s empowerment.

Ongoing Challenges for Courts

A final challenge for the rule of law concerns the need to preserve and enhance judicial independence, especially in those countries experimenting with democratic rule. Judiciaries have the potential to serve as a key mechanism to promote governmental accountability to the law. This is most apparent when they render decisions that define the scope and boundaries of executive authority. They can also play an important role in solidifying individual rights vis-à-vis the state. This includes upholding citizens’ rights to association, free expression, and due process, as well as rights against unlawful detention or loss of property at the hands of the state.

As indicated earlier, judiciaries in several countries in Africa have distinguished themselves by demonstrating that they will not simply bow to executive interests and priorities when rendering decisions in important political cases. The Ugandan and Malawian judiciaries have stood out especially in this regard over the past 15 years, but judicial independence nonetheless faces a number of different challenges in Africa today.

By virtue of their lack of control over key resources, such as enforcement powers, money, or public platforms, courts are inherently the weakest branch of government. While this is true in nearly all cases, it is especially the case in African countries given the traditional dominance of executives in political life. The behaviour of executives vis-à-vis the courts remains one of the key challenges that judiciaries face. For one, as indicated above, the executive may not comply with the decision of the courts. A report by the African Peer Review Mechanism on Kenya indicates that prominent government officials have either disobeyed or threatened to disobey court orders, a tendency, it maintains, that ‘strikes at the heart’ of the rule of law (Lansner 2010: 331).

Beyond this, courts in many countries remain institutionally subservient to other branches. Executives in most countries have substantial influence over appointments to the highest echelons of the judiciary and the funding of the judicial system. When the courts have asserted their authority they have sometimes become the target of aggressive acts by government. President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda twice sent soldiers to the courts to prevent the implementation of bail decisions. In other countries, judges have been targeted with impeachment efforts, criminal investigations, and personal harassment in the wake of rendering decisions against governments (VonDoepp and Ellett 2011).

Finally, judiciaries in many countries suffer from a perception that judges themselves are corrupt. Some executives have provided material benefits to judges or members of their families in ways that have surely compromised the independence of the courts (VonDoepp and Ellett 2011). Public opinion surveys from Ghana indicate that nearly 80 per cent of the public consider the judiciary to be corrupt (Gyimah Boadi 2010: 202). Similarly, perceptions of judicial corruption in Kenya were so severe that the judiciary became the target of a major effort to clear the courts of corrupt individuals. By some accounts, the effort has only achieved modest successes (Transparency International 2007: 224).

Conclusion

As Widner (2001) has pointed out, courts can themselves be active agents in remedying these challenges to their independence and integrity. By improving their efficiency and engaging in more effective public education, for example, they can help to build the popular legitimacy that can dissuade governments from openly interfering with them. Moreover, international agencies remain very keen to support judicial institutions, with efforts to improve efficiency and accountability at the forefront of many programmes.

Whether the glass is half full or half empty with respect to the rule of law is of course a matter of perception. What is most important to recognize is that the advances that have been registered are not irrevocable. In most African countries, constitutions, civil liberties, and courts operate in environments in which personalist tendencies remain and in which state authority is often abused by those holding office. Given this, and given the importance of the rule of law for both the overall trajectories of African polities and the everyday lives of citizens, it is quite right that the issue receives the attention that it does.

Bibliography

Bertelsmann Stiftung (2010) ‘Transformation Index of the Bertelsmann Stiftung 2010: Manual for Country Assessments’, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, www.bti-project.de (accessed 10 January 2011).

Bill Chavez, R. (2003) ‘The Construction of the Rule of Law: A Tale of Two Provinces’, Comparative Politics 35(4): 417–437.

Carothers, T. (1998) ‘The Rule of Law Revival’, Foreign Affairs 77(2): 95–106.

Diamond, L. (1999) Developing Democracy, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Donnelly, S. (2006) ‘Reflecting on the Rule of Law: Its Reciprocal Relation with Rights, Legitimacy and Other Concepts and Institutions’, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 603(1): 37–53.

Englebert, P. (2009) Africa: Unity, Sovereignty, and Sorrow, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Feld, L. and Voigt, S. (2003) ‘Economic Growth and Judicial Independence: Cross-Country Evidence Using a New Set of Indicators’, European Journal of Political Economy 19(3): 497–527.

Freedom House (2008) ‘Freedom in the World: 2008’, New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Freedom House (2010) Freedom of the Press 2010: Broad Setbacks to Global Media Freedom, New York, NY: Freedom House.

Gyimah-Boadi, E. (2010) ‘Ghana’, in Freedom House, Countries at the Crossroads 2010, New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Haggard, S., MacIntyre, A. and Tiede, L. (2008) ‘The Rule of Law and Economic Development’, Annual Review of Political Science 11: 205–234.

Harding, A. and Hatchard, J. (1993) Preventative Detention and Security Law: A Comparative Survey, Boston, MA: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Howard, R. (1985) ‘Legitimacy and Class Rule in Commonwealth Africa: Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law’, Third World Quarterly 17(2): 323–347.

Jackson, R. and Rosberg, C. (1982) Personal Rule in Black Africa, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kanyongolo, F.E. (2006) ‘Malawi-Justice Sector and the Rule of Law’, London: Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, www.soros.org/reports/malawi-justice-sector-and-rule-law (accessed 10 January 2011).

Kasfir, N. (2010) ‘Uganda’, in Freedom House, Countries at the Crossroads 2010, New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Kaufmann, D. and Kraay, A. (2002) ‘Growth Without Governance’, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2928, Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

Lansner, T. (2010) ‘Kenya’, in Freedom House, Countries at the Crossroads 2010, New York, NY: Rowman and Littlefield.

Lewis, P. (2010) ‘African Economies’ New Resilience’, Current History 109(727): 193–198.

Mamdani, M. (1996) Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Maravall, J.M. and Przeworski, A. (2003) ‘Introduction’, in J.M. Maravall and A. Przeworski (eds) Democracy and the Rule of Law, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Mutua, M. (2001) ‘Justice Under Siege: The Rule of Law and Judicial Subservience in Kenya’, Human Rights Quarterly 23(1): 96–118.

Posner, D. and Young, D. (2007) ‘The Institutionalization of Political Power in Africa’, Journal of Democracy 18(3): 126–140.

Raz, J. (1977) ‘The Rule of Law and its Virtue’, The Law Quarterly Review 93: 197–211.

Sanchez-Cuenca, I. (2003) ‘Power, Rules and Compliance’, in J.M. Maravall and A. Przeworski (eds) Democracy and the Rule of Law, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Transparency International (2007) ‘Global Corruption Report 2007: Corruption in Judicial Systems’, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

VonDoepp, P. (2005) ‘The Problem of Judicial Control in Africa’s Neopatrimonial Democracies: Malawi and Zambia’, Political Science Quarterly 120(2): 275–301.

VonDoepp, P. (2009) Judicial Politics in New Democracies: Cases from Southern Africa, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

VonDoepp, P. and Ellett, R. (2011) ‘Reworking Strategic Models of Executive-Judicial Relations: Insights from New African Democracies’, Comparative Politics 43(2): 147–165.

Widner, J. (2001) Building the Rule of Law: Francis Nyalali and the Road to Judicial Independence in Africa, New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Co.

Williams, D.T. (1978) Malawi: The Politics of Despair, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

World Bank. (n.d.) ‘Rule of Law as a Goal of Development Policy’, http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTLAWJUSTINST/0,contentMDK:20763583~menuPK:1989584~pagePK:210058~piPK:210062~theSitePK:1974062~isCURL:Y~DIR_PATH:WBSITE/EXTERNAL/TOPICS/EXTLAWJUSTINST/,00.html (accessed 10 January 2011).

Young, C. (1994) The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.