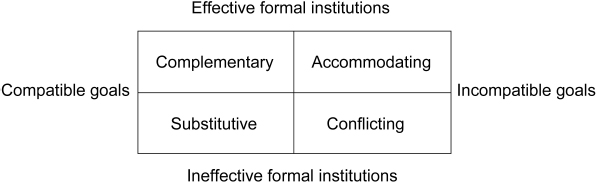

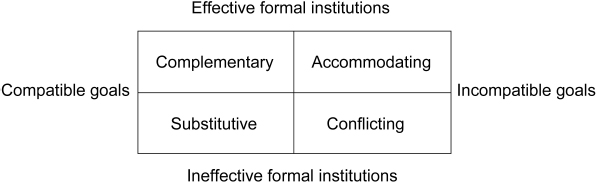

Figure 26.1Different functions of informal institutions in relation to formal ones

Source: Helmke and Levitsky 2006.

The Economy of Affection

The purpose of this chapter is to define and discuss the economy of affection, which is at the root of how African countries are being governed through a mish-mash of formal and informal institutions. Following a brief introductory discussion of where the concept belongs in the field of political science analysis, the chapter offers a definition and a set of illustrations of how it operates. It argues that although the economy of affection is most prevalent in African societies, it is a phenomenon that exists elsewhere as well. A second part of the chapter shows how the economy of affection gives rise to a varying set of informal institutions, some positive, others negative, when it comes to development. The third and final part discusses the governance implications of the prevalence of these informal institutions. The chapter concludes by suggesting that although the economy of affection is an integral – and dominant – element in political governance in Africa, it is by no means impossible to tackle and overcome when it proves to have negative consequences.

Structure and Agency in Political Analysis

Explanations in political science run the full gamut from structure, via institutions, to human agency. In examining the way scholars have studied African politics there is evidence that types of explanation have shifted over time. Thus, structuralist approaches prevailed in the 1960s and 1970s, while actor-based and institutionalist approaches came to dominate in subsequent decades.

Explanations based on structural variables acknowledge the role of history and assume that human behaviour is embedded in social and/or economic relations from which people cannot easily free themselves. Modernization theory that was influential in the 1960s presumed that the human capacity to plan and control their destiny was largely a product of such processes as urbanization, industrialization, education, and participation in the market economy. Rationalism and the ability to organize human activities on a large scale come incrementally as tradition gradually gives rise to modernity. Neo-Marxist explanations of development that replaced modernization theory in the 1970s were equally rooted in history but added the sense that progress can be accelerated through revolutionary collective action. Class struggles aimed at overthrowing backward and reactionary elites can overturn structural hindrances and pave the way for a rational and modern organization of society (see Freund, this volume). Politics – and especially the revolutionary vanguard – would spearhead this process.

The 1980s saw the rise of actor-based explanations in the form of rational choice theory. It was the polar opposite to structuralism. It started from the positivist premise that individuals are autonomous and capable of acting rationally in their own interest. Collective action occurs not as a response to structural constraints, but rather through positive aggregation of individual interests. The political arena is treated like a marketplace in which persons exchange values. This orientation was attractive to many scholars who could use it to design policies and reforms, thus making political science more prescriptive and policy-relevant. This prescriptive urge has prevailed in more recent years, although it is tempered by the addition of institutional types of analysis. ‘Good’ governance has been interpreted as the transfer of successful institutional practices, largely borrowed from the West, to countries that are described as suffering from a ‘democratic deficit’, regime instability, or a ‘weak’ or ‘failed’ state. Knowingly or unknowingly, political scientists studying these phenomena in a comparative perspective have yielded to the underlying premise that there is a single development track that begins with democracy or ‘good’ governance so defined. It has been the price paid for ensuring that Africa is not treated as an ‘exceptional’ case, but can be studied through the same lens as all other regions of the world.

This orientation, however, also carries its own limitations. It assumes a uniform model or theory for understanding complex phenomena that we know from history come in very different shapes. It relies on data sets that tell part of the full story and sometimes are nothing but stylized facts. These are real pitfalls, especially in the study of African politics, where official data are hard to come by and often unreliable. Objectification – turning individual persons into categories of people and organizing society accordingly – is only an incipient and yet to be fully institutionalized practice. Conclusions drawn from what is possible to know through the study only of formal institutions, therefore, are by necessity incomplete. There is a need to complement these studies with a focus on informal institutions, how they interact with formal ones, and what their consequences are for political governance. A useful start for such studies is an understanding of the economy of affection.

The Economy of Affection

The economy of affection as a concept has its origin in the theoretical contribution made by the Nigerian sociologist Peter Ekeh, who analyses the governance predicament in African countries (Ekeh 1975). His main argument is that African societies are characterized by two public realms: a civic and public realm that coincides with the institutional legacy of the colonial days; and a second, ‘primordial’ realm built around the local communities in which people live and work. The former is built around formal institutions, the latter around informal ones. Ekeh’s point is that moral and political conduct favours the latter at the expense of the former. To be more specific, he argues that political leaders extract resources from the civic realm to strengthen the community-oriented realm. This process has a similarity with the politics of favouring special interests that is such a prominent part of American politics, the difference being that in the United States it is subject to regulation and enforcement of the law to an extent that limits and calls into question the influence of personalized relations. Yet the phenomenon under study here is by no means unique to Africa. To the extent that it amounts to taking advantage of public office for private purposes – what is generally called ‘corruption’– it is a universal challenge.

The ‘economy of affection’ is the concept that I have coined and used in order to draw attention to this type of governance dilemma in African politics. It originates from my own studies in Tanzania and Kenya in the 1970s and early 1980s and was meant to question the extent to which mainstream explanations at that time did justice to what was going on in African countries (Hydén 1980, 1983, 1987). Thus, the economy of affection provided an alternative to explanations offered by neo-Marxist scholars who, without any real empirical evidence, used the concept of social class to explain politics and development in post-independence Africa. Being dogmatically wedded to such a theoretical apparatus, they ‘saw’ social categories in Africa that did not exist on the ground but happened to be an integral part of their analytical framework.

The economy of affection also became an alternative to the economistic, rational choice-based theory that emerged as part of the neo-liberal policies of the early 1980s. The explanation of utilitarian human behaviour provided by rational choice theory looked elegant and parsimonious when compared with the more complicated structural explanations of the previous decades. Bates (1981) comparison of agricultural policies in Kenya and Tanzania using a rational choice approach became a classic in the study of African politics. However, the notion that elites act in their own interest is no significant ‘discovery’ in political science, and rational choice proponents tend to overlook the social relations in which choice is so often embedded, not only in Africa but elsewhere as well.

The alternative explanation offered by the economy of affection rejects the assumption that individuals are autonomous social beings capable of maximizing their own interests without considering the consequences for other beings. People are born and socialized into group or community relations that they can only ignore at great expense. This happens everywhere but it is particularly significant in societies, like many of those in Africa, where most people still stand with only one foot in the marketplace. The moral code in these places is still ‘I am because we are’.

The social logic that is associated with the economy of affection, therefore, can be described as a reverse collective action problem, i.e. collective rationality overrides and undermines individual interests. Rational choice theorists like Olson (1971) have argued that individuals do not join groups or organizations if they do not perceive an immediate benefit by doing so. Based on his study of American society, he criticizes those who had previously argued that Americans are ‘joiners’, ready to join associations for some altruistic reason. In contrast, wherever the economy of affection is present, people are born into and brought up in primary social organizations like the family, clan, village, or ethnic group. The bonds of these groups are the basic social facts that determine much of not only economic but also political behaviour. Their individual autonomy is extensively circumscribed by these norms.

The point here is not that the logic of the economy of affection is so overwhelming that it pre-empts all other considerations. It functions in a context-specific way with variable consequences. In rural areas, it may still be hegemonic in the sense of determining how things get done as a result of the lower levels of information and education available to rural residents. In such cases, collective action is likely to be largely driven by moral codes associated with the economy of affection. Significantly, such codes pose a special challenge to the activities of international non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Representatives of these organizations, seeking to promote development and fight poverty, typically apply a positivist approach to development that implies modern standards of planning and implementing projects on the basis of the assumed individual rationality of participants. Even in the context of participatory analysis and learning approaches, this becomes controversial because the local social logic calls for collective action in response to needs and crises and thus tends to be intermittent, while the NGO representatives advocate an approach that is meant to make collective action locally regular and permanent. Thus, when outside support comes to an end, there is a tendency for local communities to revert to the local logic with which they are familiar. Many NGOs have experienced this outcome and it is still not clear how they can withdraw and at the same time ensure that their effort is fully understood and embraced by the communities.

The economy of affection is not just a rural phenomenon. Its logic also stretches into urban areas and is present among the elite as much as among ordinary city dwellers. Remittances from urban residents to their rural brethren are one case in point. These days, such remittances often come from members of the African diaspora and are an integral part of the country’s efforts at reducing poverty. Particularly critical is the presence of the economy of affection in government and politics. Government officials find it hard to defect or ignore obligations that are nested in reciprocal relations with people, most of whom are kinfolk from home. This has a bearing on how they perform in office. Politicians literally feed on this logic. They perform the welfare functions that in more developed states are carried out by government departments based on specific budgetary allocations (Barkan, this volume). The economy of affection does not know such boundaries or limitations. Its logic trumps the civic and public one, as Ekeh argued in his piece many years ago.

So, how is the concept best defined? The easiest way of describing the economy of affection is to suggest that it is constituted by personal investments in reciprocal relations with other individuals as ways of achieving goals that are seen as otherwise impossible to attain. Sought-after goods – whether material or symbolic, such as prestige and status – have a scarcity value. Because they may be physically available but not accessible to all, people invest in relations with others to obtain them. This economy differs from capitalism as well as socialism. Money is not an end in itself, nor is the state the primary redistributive mechanism. It relies on the handshake rather than the contract, on personal discretion rather than official policy, to allocate resources. It co-exists with capitalism or socialism, often helping individuals to get around the ‘rough edges’ of such systems. Exchanges within the economy of affection do not get officially registered. As such, it is an invisible economy for which conscientious policymakers have no taste and economists find no real way of effectively incorporating into their conventional forms of analysis.

Informal Institutions

Informal institutions are the clearest manifestation of the economy of affection. The latter is not an expression of irrationality or altruism, nor does it have anything to do with romantic love. It is a practical and rational way of dealing with choice in contexts of uncertainty and in situations where place, rather than distanciated space, dictate and influence people’s preferences. People engage in affective behaviour and create informal institutions for a variety of reasons. They may do so from a position of either strength or weakness. They may do it when faced with either an opportunity or a constraint. Four motives for engaging in affective behaviour will help illustrate it here: to gain status; to seek favour; to share a benefit; and to provide a common good. As a form of ‘moral economy’, the economy of affection is more diverse and produces a wider range of informal institutions than is acknowledged, for example in Scott’s studies of the moral economy in Southeast Asia (Scott 1976, 1985). The latter tends to confine the understanding of the moral economy to how poor peasants defend their life-world against intrusion by capitalist and other outside values and norms.

Informal institutions are forms of regularized behaviour. They arise for a variety of reasons. They may complement formal institutions by adding moral and political strength to official policy measures. For example, a charismatic political leader may create enthusiasm about a policy initiative that otherwise would have been difficult to implement. Informal institutions may also substitute for formal ones. This happens when the latter are either absent or ineffective. An example would be when people take the law into their own hands because the police are not there or lack the means to maintain law and order. A third scenario is when formal institutions accommodate informal ones. The former are effective but sometimes their own effectiveness may raise issues of political legitimacy. They are simply pushing their agenda with too much insistence and to avoid a political crisis, they become accommodating of opinions expressed through informal means, such as an unofficial caucus group. A fourth scenario is when informal institutions undermine formal ones because their respective objectives are different. An obvious example would be when the habit of paying bribes has been institutionalized to the point where the law of the land is consistently broken. In their study of informal institutions in Latin American politics, Helmke and Levitsky (2006) offer a useful classification of these different scenarios, as shown in Figure 26.1.

Figure 26.1Different functions of informal institutions in relation to formal ones

Source: Helmke and Levitsky 2006.

The point that the authors make is that the functions of informal institutions vary according to two dimensions: whether formal institutions are effective or not, and whether the goals that are pursued are compatible or incompatible. Because formal institutions in most African countries remain weak, the most common scenarios there are associated with the boxes on the lower half of the diagram.

Substitutive Institutions

There are plenty of examples of where informal institutions in Africa take on the role played by formal ones in other societies. Four types of informal institutions that have largely played a substitutive role are briefly discussed here.

Clientelism

Although clientelism is by no means a uniquely African practice, it is generally recognized as one of the prime hallmarks of politics on the continent. It is a way of conducting politics through patronage. Political leaders try to secure the support of underlings by distributing favours that cement relations of power. Although it is not gender-specific, it is typically associated with masculine power figures. Lemarchand (1972) rendered the first systematic account of clientelism in African politics. His treatment of this informal institution was quite appreciative: a political patron brought to the political centre a large following that facilitated national integration. In retrospect, one may argue that Lemarchand’s treatment of clientelism is the informal equivalent of Lijphart’s (1977) ‘consociationalism’ – the political order found in some multi-cultural countries in Western Europe. Even in these European countries, the political centre has been held together by a series of ‘deals’ among representatives of cultural groups sharing state power.

This positive account of clientelism has gradually become more critical, if not negative. ‘Neopatrimonialism’– the ultimate form of clientelism in politics – has become the principal concept in Africanist political science (Erdmann, this volume). Political rulers treat the exercise of power as an extension of their private realm. The prevalence of clientelism in African politics is evidence that formal institutions are weak. The introduction of multi-party politics has tended to reinforce affective relations, because competition for power and resources has intensified in the new political dispensation (Bratton and van de Walle 1997). Although clientelism is therefore deemed problematic, especially in circles that are concerned with improving governance in African countries, there are some scholars who search for the seeds of a developmentally friendly patrimonialism (see Kelsall, this volume).

Pooling

The concept of pooling is sufficiently general to serve as a generic classification of all forms of cooperation in groups that are organized along voluntary and self-enforcing lines. These groups are not sanctioned by law; instead, they are constituted by adherence to unwritten rules. The family is the most basic social organization and it features, directly or indirectly, in many of the examples of lateral informal institutions that can be found around the world. Informal institutions in which the family is important prevail in societies where voluntary associations such as schools, clubs, and professional organizations, have yet to acquire influence in society. As Fukuyama (1995: 62–63) notes, cultures in which the primary avenue to sociability is family and kinship, rather than secondary associations, have a great deal of trouble creating large, durable economic organizations and therefore look to the state to support them (see also Putnam 1993).

The African family is typically extensive and generally open to cooperation with others. Cousins, even distant ones, are brothers and in each household it is not uncommon to find members of three or four generations living together. Kinship relations dominate, facilitating solidarity across family lines. This mode of organizing is also replicated outside the kinship network, but typically on a small scale. Rotating credit societies are one example; groups sharing labour another. Groups like these, however, are not necessarily as effective today as they used to be. Integration into the global economy means that gaining resources needed for one’s livelihood involves transactions outside the local community. Instead, wealthier individuals in the community may become brokers with the outside world and use this role to build a position of power. Pooling gives way to clientelism.

Self-Defence

Self-defence refers to informal institutions that mobilize support against a common threat or enemy, whether real or perceived. Affection is a powerful instrument to achieve this, as it binds people together across narrower organizational boundaries. In these instances, formal law enforcement institutions do not perform the role that they should. Modern African history is full of examples of how affection has been used to generate movements for defence of what is perceived as an African lifestyle. More recently, informal self-defence mechanisms have emerged in response to threats of violence. The sungu sungu vigilante groups in Tanzania are an example of such an informal institution that has a nationwide presence. The popularization of this institution has, by and large, led to greater security wherever they patrol. Instances of popular justice involving these groups have been reported but they are not the principal outcome.

The use of affection in self-defence is a more pronounced phenomenon in Africa than in Asia. A major reason is that Asian societies have generally been permeated by a single religion or philosophy. For example, Confucianism has defined social relations in China over 2,000 years. Even though its ethical principles have not been in the form of a national constitution, many Chinese, regardless of social status, have internalized these principles (Rozman 1991). By contrast, in Africa customary norms were never universal and were generally confined to small-scale societies. Although similarities did exist among these societies, usually they were not enough to form the basis for a national constitutional and legal framework. Instead, what has held the new nation-states together is a perceived need to guard against an enemy from within or without. Initially the enemy was the colonial power. After independence, there have been examples of internal enemies being fought in the name of getting rid of autocratic rulers. Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Uganda are cases in point. Although these campaigns or struggles have often been couched in ideological language, they have been sustained by close affective ties – in Ethiopia, centred on the Tigray group; in Rwanda on the Tutsi group; and in Uganda, the Hima.

Charisma

Charisma, one may argue, is the ultimate informal institution. ‘Charismatic’ leadership, according to Weber, is ‘devotion to sanctity, heroism or exemplary character of an individual person, and the normative patterns or order revealed or ordained by him’ (Weber 1947: 242). Weber applied it broadly to refer to all individual personalities endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities. This included a great variety of people, like heroes, saviours, prophets, shamans, and even demagogues. Weber himself is not easy to understand on the issue of what charismatic authority really is, but, in short, his treatment of the concept is meant to capture the revolutionary moment in history. At the same time, he makes the point that charisma is not sustainable without routinization. In the study of law and administration, scholarship has treated the role of charisma as instrumental in transforming traditional or customary authority into a new type, called, in Weber’s language, ‘rational-legal’ authority. In Africa, the story of charisma is different. It seems important especially in terms of filling the gap that exists between formal institutional structures on the one hand, and customary and informal institutions on the other.

The interesting thing about Africa is that charisma typically works to re-establish traditional, rather than rational-legal, authority. The affinity with the modern common or civil law that was brought to Africa by the colonial powers is virtually non-existent, except in professional legal circles. What counts are the principles of the past that a charismatic figure – a politician or a religious minister – can invoke in order to gain followers. By wishing to reinvent something genuinely ‘African’, these persons seek legitimacy based on the sanctity of age-old rules and powers. This is inevitably a process of informalization. Compliance in this scenario is not owed to enacted rules but to the persons who occupy positions of authority or who have been chosen for it by a traditional master. Galvan (2002) provides an intriguing and empirically rich case study of how this process works among the Serer in rural Senegal. Innovations or adaptations, even if they lead to ‘syncretic’ institutions – a merger of formal and informal norms – are legitimized by disguising them as reaffirmations of the past.

Charisma blurs the line between person and rule. It assumes a reciprocal exchange in which the authority of the charismatic figure is accepted without question. These exchanges are essentially affective in nature. No attempt is made to reflect on a particular principle before accepting authority because charisma makes such reflection superfluous. Many African nationalists were charismatic figures. No one succeeded more than Julius Nyerere in trying to disguise his modernist policies with reference to the sanctity of past rules. He developed socialist policies with a modern economy in mind, but legitimized every initiative he took in that direction with reference to recreating an ideal of the African past (ujamaa). The other more controversial side of Nyerere’s policies is that the informal institutions he created inhibited a critical examination of his policies from within. Instead, they fostered conformity and compliance (Hydén 2006).

While substitutive informal institutions may at times become controversial, they generally cause less controversy than those that are in outright conflict with formal institutions. The substitutive type of informal institutions often acquire a measure of political legitimacy that the formal ones do not have or have lost. In scenarios where the two types are in conflict, one of three outcomes is possible: collapse, stalemate, or reform.

Collapse

Collapse may occur in situations where the formal and informal institutions tear on each other until they both lose their legitimacy, and chaos or anomie replaces order. Violence, as occurred in Kenya after the December 2007 elections, is one example; what happened after the elections in Côte d’Ivoire in 2000 provides another. While in Kenya, credible formal institutions have been adopted and approved in a referendum in 2010, the violence in Côte d’Ivoire led to further and more widespread acts, and it is too early to say whether the 2010 election has served as a catalyst for change toward peace and order. What these cases indicate is that countries that are – or at least were – renowned for stability and relatively high levels of development may suffer heavily if informal and formal institutions are at loggerheads and thus undermine each other’s legitimacy.

There are many other countries in Africa where such a scenario has played out but where the consequences have been even worse. The collapse of the state in Somalia is perhaps the most noteworthy, but the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Central African Republic, and Chad are other equally worrisome cases. The humanitarian costs of the collapse – or near-collapse – of formal institutions in these countries are a big burden and one that is very difficult to remove. Informal institutions have been able to function only in local contexts and have failed to bring together political factions from different localities, as the failure to form an effective government in Somalia and the DRC indicates. Neopatrimonalism or clientelism has proved inadequate to overcome the political challenges caused by these collapses.

Stalemate

Stalemate is likely to happen in situations where formal and informal institutions live side by side in a competitive manner, but where the stakes are mainly individual rather than public. A case in point would be what happens in government offices where the principles of a legal-rational bureaucracy face the moral code of the economy of affection. Civil servants are expected to be impartial and make judgments based on meritocratic criteria. Such are the rules of the Weberian model of bureaucracy. Yet, most civil servants occupy their position fully aware that they cannot ignore demands from kinfolk and others with whom they have mutual obligations based on social criteria. Most occupants of government office in Africa know how to live with this conflict, but by paying attention to both, the delivery of public services and goods tends to suffer. An anthropological study of corruption in three West African countries – Benin, Niger, and Senegal – illustrates in great detail how these attempts to cope with both formal and informal institutions can lead to stalemate and poor performance (Blundo and Olivier de Sardan 2006). The reverse collective action problem is very much present in African civil services and, despite ambitious public-sector reform programmes, not much has changed since the 1980s when a study of civil servants in Southern Africa revealed a similar pattern (Montgomery 1987).

Reform is the scenario in which formal institutions prevail over informal ones, and the reverse collective action problem is solved in favour of a Weberian-type bureaucracy in which the norms of a legal-rational system of administration are institutionalized. Despite concerted efforts to reform the civil services in African countries, initially funded from local sources but in the past two decades financed almost exclusively by the World Bank and other donors, very little has been accomplished. A few countries, like Botswana and Mauritius, have the features of a Weberian bureaucracy and their civil services are deemed quite dependable and free from corruption. Reform efforts elsewhere in Africa have not really yielded significant improvements. Studying the initial reform efforts, Rweyemamu and Hydén (1975) conclude that politicization of the civil service, nepotism, and widespread red tape were the main reasons for poor performance. A review carried out over a quarter-century later identified the same factors among the most important explanations for performance shortcomings in African governments (Olowu 2003). As suggested above, civil services find it hard to break out of the hold that the economy of affection has over human choice and behaviour through its various informal institutional mechanisms. This persistent inability to reform African civil services with the help of measures that work elsewhere has led to a search for solutions from within. Rather than seeing the issue in terms of a ‘governance deficit’, there is a greater readiness to explore which aspects of indigenous institutions work well enough to constitute the basis for reform (see Kelsall, this volume). Although we know too little about the prospect for success of such an approach, Rwanda’s reconstruction programme after the 1994 genocide is sometimes held up as a successful example of progress based on local institutions.

Political Governance

The tensions between formal and informal institutions are at the core of how African countries are being governed. Patronage co-exists with policy as the driving force in politics; clientelism operates side by side with the rule of law; and autocracy occurs in tandem with democracy. Viewed through a Western democratic lens, virtually all countries in Africa are ‘hybrid’ states or, as Collier and Levitsky (1997) would describe them, ‘diminished sub-types’ of mainstream conceptualizations based on the Western experience. This description, however, does not imply that there is never any change in the political systems of these countries. It is there precisely because the tensions between formal and informal institutions keep these countries in perpetual movement, even if it is usually not clear whether these changes really are decisive and sustainable. Nor does hybridity mean that all countries are the same: it produces both positive and negative outcomes. Furthermore, the way informal institutions are applied varies from country to country depending on social context. A comparison between Kenya and Tanzania serves as an illustration of at least one significant variation in political governance.

The two countries make an interesting pair for comparison. They have similar colonial legacies: they are both located on the shores of the Indian Ocean with its unique Swahili culture; and both are multi-ethnic societies. After independence, however, they adopted different development policies: Kenya followed a more capitalist road (albeit in the guise of African socialism), while Tanzania experimented with moving forward on a socialist path. This distinction was for many years the principal criterion for comparing the two countries (e.g. Barkan 1994). More recently, following the wave of democratization in the 1990s, comparing the two has been much less common. Instead, they have been compared to other countries and placed on a global scale of democratization or good governance. This shift has encouraged a focus largely on the performance of formal institutions, with informal ones being treated as evidence of shortcomings. The result is that the mechanics of informal institutions have either been ignored or condemned. The campaign against what Westerners call political corruption is a case in point (cf. Olivier de Sardan, this volume).

Political governance in African societies is never fully understood without attention to informal institutions and how they operate. Kenya and Tanzania are again examples of two different modes. Although both countries are multi-ethnic, the make-up of ethnic relations is different. Kenya’s ethnic map is dominated by a half-dozen large ethnic constellations, all of which still consider themselves occupants of their own homeland. Despite a high rate of urbanization – and an increasing rate of inter-ethnic marriage – the attachment to land in specific parts of the country prevails. The boundaries on Tanzania’s ethnic map are much more blurred. First, the number of ethnic groups is large, and many of them are very small and often in some way related to their neighbours. Second, the widespread use of Kiswahili has meant that ethnic profiles have become less significant and are typically subordinated to a national identity. Finally, urbanization and inter-ethnic marriage have helped to further erase local identities based on ethnic group.

These different ethnic maps have also translated into two distinct forms of politics. In Kenya, ethnic boundaries have tended to be exclusionary, thus engendering the need for elite alliances or coalitions. In Tanzania, where ethnic boundaries have been less exclusionary and easier to transcend, a national political elite cadre has emerged that shares a similar normative outlook. The result is that the role of informal institutions in Kenyan politics has been especially prominent in cementing relations across ethnic boundaries. In Tanzania, on the other hand, the same institutions have been more often applied to secure popular support. In Kenya they have been applied horizontally, in Tanzania vertically. Political events in recent years illustrate this difference between the two countries.

Elections are especially significant mechanisms that offer great insight into how informal and formal institutions interact. Much power is at stake in these events and informal institutions, not only in African countries but elsewhere too, grow in importance as tools to gain advantages. The risk of fraud, violence, and other negative outcomes is particularly high. This proved to be the case in the 2007 Kenyan elections when ethnic competition erupted into violence after President Mwai Kibaki, the Kikuyu incumbent, was declared the official winner despite accusations from opposition leaders and some international observers of electoral manipulation. Kikuyus were attacked by other ethnic groups, especially in areas in which they constituted a minority, while pro-government police and militias were deployed in revenge attacks against their predominantly Luo and Kalenjin rivals (see also Lynch, this volume). In total, over 1,000 people were killed and hundreds of thousands made homeless. The events were a shock not only to Kenyans but to the outside world as well.

After a few weeks, during which other African leaders (including former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan) played a role, Kenya’s political leaders formed a government of national unity, bringing together key representatives of each ethnic group. Even though its operations were characterized by tension and the financial costs of creating a mega-government were high, the coalition has held together sufficiently well to steer the country in a new direction. The new government has even successfully completed the constitutional reform process, which had been repeatedly started and stalled since the reintroduction of multi-party politics in the early 1990s (Chege 2008). In 2010 a popular referendum supported by both President Kibaki and his main rival, Raila Odinga, overwhelmingly approved a new constitution that (among other things) limited the powers of the president, made him and his cabinet more accountable, and encouraged a degree of decentralization. Perhaps most important of all, a series of formal institutions were put in place to monitor the implementation of the constitution. In retrospect, one can argue that the misuse of informal institutions triggered the ‘Kenya crisis’, but it is also important to note that the very same institutions, notably ethnic networks and coalitions, subsequently supported the restoration of formal institutions in the name of the new constitution. Thus, the crisis created by the tensions between the two types of institutions was this time resolved in favour of the formal ones. Whether this is a reformative breakthrough it is too early to say, but Kenyans and others will follow with great interest how the country’s political elite behaves.

If the political fissures in Kenya are primarily along ethnic lines, and informal institutions, notably clientelist patronage, are used to pre-empt or repair these cleavages, the most obvious division in Tanzania is between the elite and the ‘masses’. Informal institutions are used by individual politicians to buy the support of ordinary people, a habit that was as evident in the 2010 election campaigns as in previous elections, despite laws limiting the amount a given candidate could spend and prohibiting bribery of the voters by offering gifts. The ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) has never lost an election in a multi-party setting and takes its indispensability for the country’s development and security for granted. Any challenge to its hegemony, therefore, is met with strong measures: some formal, such as use of the security forces; others informal, like trying to co-opt members elected to the opposition (Whitehead 2009). The camaraderie among the political elite in Tanzania is such that a ‘brown envelope’ – the symbol of a bribe – is often used to silence opposition or stopping its representatives from revealing uncomfortable political truths about how the country is being governed. The outcome of the 2010 election was no different from previous ones: CCM won big, although the opposition made significant gains in the wealthier northern parts of the country – an indication that the inclusionary character of Tanzanian politics is being challenged. Informal institutions may prove, as in Kenya, less effective than they have been in the past in maintaining peace, stability, and development in the country.

Conclusion

The economy of affection does not explain everything in Africa, but it does play its part in explaining how African countries are being governed as it generates the informal institutions that are so crucial to what happens – both positive and negative. Informal institutions are an integral part of the governance equation and their interaction with formal institutions is one of the most central fields of study in African politics. Far too much attention has been given by scholars and policy analysts alike to directly transferring formal institutional practices that are neither rooted in African social realities nor responsive to the social logic of the economy of affection. It is no surprise, therefore, that government reforms have fallen far short of expectations and that governance in most countries rests on a shaky foundation. At the same time, as the Kenyan example illustrates, Africans are ready to internalize new formal practices but want to do so on their own terms and in response to the challenges that they face internally, not in order to please the outside world and its conditionalities.

Bibliography

Barkan, J. (ed.) (1994) Beyond Capitalism and Socialism in Kenya and Tanzania, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Bates, R.H. (1981) Markets and States in Tropical Africa, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Blundo, G. and Olivier de Sardan, J.-P. (2006) Everyday Corruption and the State: Citizens and Public Officials in Africa, London: Zed Press.

Bratton, M. and van de Walle, N. (1997) Democratic Experiments in Africa, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Chege, M. (2008) ‘Kenya: Back from the Brink?’ Journal of Democracy 19(4): 125–139.

Collier, D. and Levitsky, S. (1997) ‘Democracy with Adjectives: Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Politics’, World Politics 49(3): 430–451.

Ekeh, P. (1975) ‘Colonialism and the Two Publics in Africa: A Theoretical Statement’, Comparative Studies in Society and History 17(1): 91–112.

Fukuyama, F. (1995) Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity, New York, NY: Free Press.

Galvan, D.C. (2002) The State Must Be Our Master of Fire: How Peasants Craft Culturally Sustainable Development in Senegal, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Helmke, G. and Levitsky, S. (2006) Informal Institutions and Democracy: Lessons from Latin America, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hydén, G. (1980) Beyond Ujamaa in Tanzania: Underdevelopment and an Uncaptured Peasantry, London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Hydén, G. (1983) No Shortcuts to Progress, London: Heinemann Educational Books.

Hydén, G. (1987) ‘Capital Accumulation, Resource Distribution, and Governance in Kenya: The Role of the Economy of Affection’, in M. Schatzberg (ed.) The Political Economy of Kenya, New York, NY: Praeger.

Hydén, G. (2006) African Politics in Comparative Perspective, New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Lemarchand, R. (1972) ‘Political Clientelism and Ethnicity in Tropical Africa: Competing Solidarities in Nation-Building’, American Political Science Review 66(1): 91–112.

Lijphart, A. (1977) Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Montgomery, J.D. (1987) ‘Probing Managerial Behavior: Image and Reality in Southern Africa’, World Development 15(4): 518–544.

Olowu, D. (2003) ‘African Governance and Civil Service Reforms’ in N. van de Walle, N. Ball and V. Ramachandran (eds) Beyond Structural Adjustment: The Institutional Context of African Development, New York, NY: Palgrave.

Olson, M. (1971) The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Putnam, R. (1993) Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Italy, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rozman, G. (ed.) (1991) The East Asian Region: Confucian Heritage and Its Modern Adaptations, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rweyemamu, A. and Hydén, G. (eds) (1975) A Decade of Public Administration in Africa, Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau.

Scott, J.C. (1976) The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Scott, J.C. (1985) Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Weber, M. (1947) The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Whitehead, R. (2009) ‘Single-Party Rule in a Multiparty Age: Tanzania in Comparative Perspective’, unpublished PhD thesis, Temple University.