RICHARD A. NIELSEN

▶ FIELDWORK LOCATION: CAIRO, EGYPT

The first word the angel Jibril spoke to the Prophet Muhammad was a command: “Recite!”

May 30, 2011. It is my first day in Cairo. I have no fixer, no translator, and no connections.1 I definitely have no wasta, the social currency of reciprocity that often gets the job done in Egypt. Naturally, the newscaster Arabic from class isn’t getting me far, and although I’ve theoretically learned some of the local dialect too, it is unfamiliar in my mouth and my ears. Finding my hotel takes several hours of questioning strangers on the street; I leave a trail of confused and amused Egyptians behind me. I am here to study Muslim clerics, but I have no plan other than to walk into mosques and see what happens. This does not seem like an auspicious start.

A few hours later, I have planted myself on the floor at the back of the mosque in al-Husayn Square. The mosque is an imposing building in the heart of Old Cairo that commands the busy square in front of it, with shoppers streaming by on their way to wander the maze of Khan al-Khalili bazaar. This is no mere neighborhood mosque. It has existed in some form for eight hundred years and is one of the holiest sites in Egypt. But I don’t know this when I walk in. Instead, I’m at the al-Husayn mosque because it is across the street from where I would really like to sit, at the renowned al-Azhar mosque/university complex. I want to test the waters first.

I sit at the back, cross-legged on lush green and gold carpet dappled with stylized leaves and punctuated by row upon row of marble columns soaring up to meet the roof arches. I watch pilgrims filing in to visit the shrine believed to be the final resting place of Imam al-Husayn’s head. I start sketching. Then I sneak a few photographs. Are cameras allowed here? I accept a piece of bread from someone offering food to worshipers. I haven’t spoken to anyone, but I don’t really want to. I just want to observe without being singled out.

Someone takes an interest in me. First, some glances at my notebook. Then at my camera. Then perhaps at my blond hair. More at the notebook. He moves closer. Now insisting that I stand: “What are you doing here? What do you want? American spy?” Is this serious? He looks serious. The young man is maybe twenty, wiry and shorter than I am, clean-shaven, wearing a traditional dark gray ghalabiyya, and holding a Qur’an. I start to think that I’ve made a mistake. It has been three months since the January revolution, and a vigilante spirit has taken hold; neighbors protecting neighbors as the state recedes.

I try to explain that I am a student interested in Islam. There are more questions. I can’t understand. A small crowd is gathering. The young man presses me for answers, looking increasingly displeased. It is becoming a scene. This does not seem like an auspicious start.

FIGURE 3.1 Inside the al-Husayn mosque. Are cameras allowed here?

Desperate, I offer to recite the Fatiha—the evocative opening chapter of the Qur’an—as a token of my sincerity. I’ve just barely memorized it during my layover in Frankfurt. The moment the offer leaves my lips, I regret it. I am likely to mess up.

Yet as soon as I begin, the change is palpable.

Bismillah ar-Rahman ar-Rahim

Al-hamdu lillahi rabb al-’alamin

Ar-Rahman ar-Rahim Maliki yawm id-din

Under pressure I forget the beginning of the next line, and the same skeptical young man is now eagerly supplying the missing syllables, urging me to succeed.

Iyaka na’abudu wa iyaka nasta’in

Ihdina sirat al-mustaqim

Sirat alladhina an’amta ‘alayhim

Ghayr al-maghdub alayhim wala ad-dalin

I finish to exclamations of “ya ustaz!” (O teacher!) and “ma sha’ allah!” (look what God has wrought!). The group has grown during the recitation, so I am surrounded now by what feels like a dozen men of varying ages, mostly young, their piety evident from prayer marks on their foreheads. More onlookers remain seated close by. Cell phones appear. I now face a dozen cameras, for which I perform the Fatiha again. This time, I recite more confidently. The crowd begins to disperse, evidently assured that I am not a threat. Have some mistakenly concluded that I’m Muslim? I’m not sure. The earnest young man writes his phone number and name in my field notebook: Nasir, the Arab name for “one who gives victory.” He insists that I call him the next day so that he can show me around. There are no more questions about whether I am an American spy.

It would neatly tie together a great story if Nasir had become a key interlocutor during my time in Egypt. He certainly could have been. He was a twenty-two-year-old religious student, precisely the demographic I was hoping could give me an entrée into the world of al-Azhar. But we met once or twice and then drifted apart. Nasir lost interest when it became clear I wasn’t going to convert to Islam, and I found another set of friends at al-Azhar. Fieldwork relationships are complicated, and fieldwork stories often have loose ends.

I have never heard reciting scripture endorsed as a research method for political scientists. Let me endorse it for you now.

Why should political scientists memorize and recite scripture? If you want to understand how pious people think, act, mobilize, protest, vote, and generally do politics, you would do well to understand their religious practices. If memorizing holy texts is a central ritual, then memorize those texts!

Memorizing and reciting portions of the Qur’an has had at least three essential effects on my research. First, it is impossible to understand the layers of meaning in the speech of religious actors if you do not have some command of key holy texts. After memorizing the thirty-one shortest chapters of the Qur’an, I began to hear them quoted everywhere. References to them abound in phrases that had previously escaped my notice. I began to understand sermons better. I learned to pray properly because Islamic prayer incorporates Qur’an recitation. I began to pick up on mistakes: the prominent cleric Yusuf al-Qaradawi stumbling over some words while quoting a verse on his Aljazeera show and getting some help from his cohost.

The most advanced Muslim scholars memorize the entire Qur’an, often as children. At my best, I had one-sixtieth of the Qur’an memorized, and certainly not as well. If this small portion opened new rhetorical worlds to me, I strongly suspect that there are at least fifty-nine more layers of meaning that I’m missing out on by not having memorized the rest.

Second, I memorize and recite scripture as a practice of participant observation2 that allows me to gain interpretive insight. Most political scientists are trained in a strictly positivist orientation, where learning happens by observing. But there is also such a thing as learning by doing. Religion, in fact, often relies heavily on learning by doing, which is one reason merely observing religion without practicing it has sometimes led political scientists to adopt impoverished views of the role of religion in political life. I can’t claim any formal training in methods of participant observation. Instead, I found myself drawing on my childhood years of Mormon Sunday School to develop a research philosophy of learning by doing—paying attention to how I felt, thought, and behaved during and after my memorization. I know why Qur’an reciters cup their hands to their face: feeling the tone from your mouth buzz into your ear via your hand helps you stay on tune in a crowded space. I know why religious students at the teaching mosques memorize their textbooks, because I know what it feels like to engage with an authoritative text through memorization rather than critique.

The intellectual tradition most associated with this mode of learning is interpretivism; defined by Timothy Pachirat as “humans making meaning out of the meaning making of other humans.”3 Although interpretivism is not mainstream in American political science, I found that the interpretive practices I adopted in my fieldwork4 were essential to helping me produce solid positivist political science in my book Deadly Clerics.5 In it, I make the case that Muslim clerics, including jihadist clerics, understand themselves to be academics. When jihadist preacher Anwar al-Awlaki discusses his influence on the Fort Hood shooter, he calls Nidal Hassan “my student.” When the leader of ISIS, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, faces questions about his qualifications to lead, he releases an academic biography. And when jihadist ideologue Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi wants to defend his place in the jihadi firmament, he touts his high citation count.

This interpretive move of trying to see jihadists as they see themselves was the genesis of my argument that clerics are far more likely to become jihadists when their academic ambitions in mainstream Islamic legal academia are blocked. The rest of the book supports this claim through a combination of standard positivist approaches: regression analysis and case studies. But I did not merely use interpretive ethnography to understand the context before proceeding with the “real” analysis. Without the interpretive insight, the regressions would have been totally different. To my knowledge, variables such as “Does this person have a PhD in the Islamic Sciences?” and “Does this person report having memorized the Qur’an on their CV?” have not appeared in any other regression analysis of jihadists. As a result of my experience integrating interpretive and positivist methods, I share with Lisa Wedeen the optimistic view that “interpretive social science does not have to forswear generalizations or causal explanations and that ethnographic methods can be used in the service of establishing them. Rather than taking flight from abstractions, ethnographies can and should help ground them.”6

Third, memorizing the Qur’an has helped me build respectful relationships in the field. Striving for friendship and rapport with those you meet in the course of your research is its own reward, and it is an essential ethical posture for fieldwork. And by maintaining a disposition of respect, I find that other good things tend to follow. My interlocutors in Cairo seemed to sense that my efforts to understand Islam were sincere, and they responded far more generously than they might have if they thought I had ulterior motives. In a separate incident from the one I described here, an Egyptian told me that “I couldn’t be CIA because they could never memorize the book of God.”

I have ambiguous feelings about advertising that I have memorized parts of the Qur’an to put my interlocutors at ease. Is it patronizing? Sacrilegious? Manipulative? Yet when I have been on the receiving end, I found similar researcher behavior endearing rather than off-putting. While in graduate school, I was part of a Mormon history reading group with about twenty other Mormons and ex-Mormons. Max Mueller, a non-Mormon scholar of American religions, came to one of our sessions to talk about his book project7 and won my trust in part because of his mastery of Mormon lingo and slang. The content of his memorization was not holy scripture—in part because Mormons don’t memorize the Book of Mormon the way Muslims memorize the Qur’an—but it performed the same role. I appreciated the high price he had paid for near-native fluency in the specialized language of Mormonism.

Chances are, memorizing the Qur’an is not exactly what you need for your fieldwork. It turned out to be an asset for me when working with Muslim clerics, but your mileage may vary. Even if you are working in a Muslim context, don’t intentionally get into risky situations expecting that rattling off the Fatiha will get you out! And as is often the case, who you are influences how people react. Things might have played out differently if I were a woman, for example.

So what can you do?

See through your interlocuters’ eyes, hear through their ears, and speak with their idiom if you can. This may save you from deeply misunderstanding the meaning and purpose of what they do.

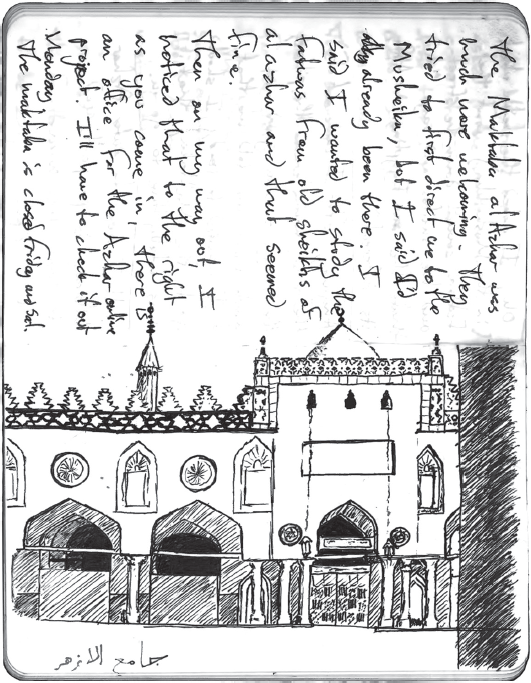

FIGURE 3.2 My sketch of the inner courtyard of the al-Azhar mosque. The sketch conveyed to them that I respected something they loved.

Be open to what Lee Ann Fujii calls “accidental ethnography”—the observations that you make about the places you are when you’re not “on the clock” executing your research plan.8 My encounter on my first day in Cairo was the product of a dozen accidents. My inability to plan for my fieldwork landed me in the mosque. A chance encounter led to a confrontation. A desperate recitation led to its productive resolution. Perhaps my poor planning made me especially open to accidental fieldwork, but I think even those executing the most fully planned field activities should remain open to serendipity.9

Figure out how to respect what the people you are studying value. This, I think, was the key reason Qur’an memorization meant so much to my interlocutors in Cairo. As pressure to publish relentlessly ramps up for junior scholars, there is a temptation to employ smash-and-grab fieldwork tactics: get in, run the experiment/survey/regression, get out, write it up. This mode of research makes it all too easy to treat our interlocutors in the field instrumentally rather than respectfully.

Memorization isn’t the only way to credibly convey your genuine respect. I like to sketch, and although I make my fieldwork sketches for myself, I find that they are quite popular with those I am interviewing. Several students at the al-Azhar mosque, for example, were quite taken with a sketch I made of the inner courtyard, and they subsequently invited me into their study circle. Like Qur’an memorization, the sketch conveyed to them that I respected something they loved.

Building a relationship with your interlocutors is an essential skill for the field, and understanding them is a precondition for doing good work. I can’t tell you how to do it. Your field site is different from mine, and people value different things. Instead of religious practices, it may be an appreciation of tradition, a shared struggle, a counterculture, or something else entirely. But everyone makes meaning out of their life. Your fieldwork will be more successful if you can figure out how they construct that meaning and find ways to convey to them that you understand. No matter how positivist your research design, figuring out how other people make meaning out of their lives is an interpretive task.

______

Richard A. Nielsen is associate professor of political science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

PUBLICATION TO WHICH THIS FIELDWORK CONTRIBUTED:

• Nielsen, Richard A. Deadly Clerics: Blocked Ambition and the Paths to Jihad. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

NOTES

1. Thank you to Bernardo Zacka, Marsin Alshamary, Chappell Lawson, Sarah Parkinson, Peregrine Schwartz-Shea, Gabriel Koehler-Derrick, Jillian Schwedler, and Timothy Pachirat for inspired comments. I am forever indebted to my friends from the field, especially Diaa’, who guided me around Cairo arm in arm.

2. A note about terminology: the term participant observation denotes the research practice of learning about a culture through participation and observation at close range. Participant observation is often used synonymously with ethnography, which Spradley defines as “the work of describing a culture”: James P. Spradley, Participant Observation (Long Grove, Ill.: Waveland Press, 2016,) 3. But I see useful daylight between the two. Ethnography has become laden with expectations about the duration and depth of a researcher’s cultural immersion. People will look at you askance if you claim to do ethnography with less than six months at a field site. Participant observation eludes the weight of these expectations. You can practice it in mere minutes by asking, What am I seeing, hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling that might help me understand how the humans constructing this culture make meaning out of their lives? For me, the mental shift this question evokes can transform a profoundly mundane situation into a fieldwork episode teeming with possibilities for insight.

3. Timothy Pachirat, “We Call It a Grain of Sand: The Interpretive Orientation and a Human Social Science,” in Interpretation and Method: Empirical Research Methods and the Interpretive Turn, ed. Dvora Yanow and Peregrine Schwartz-Shea, (New York: Routledge 2006), 426–32. For more, see Lisa Wedeen, “Conceptualizing Culture: Possibilities for Political Science,” American Political Science Review 96, no. 4 (December 2002): 713–28, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055402000400; Edward Schatz, Political Ethnography: What Immersion Contributes to the Study of Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Dvora Yanow and Peregrine Schwartz-Shea, eds., Interpretation and Method: Empirical Research Methods and the Interpretive Turn (New York: Routledge, 2015).

4. I conducted fieldwork in Cairo in May–June 2011 and April–May 2012. The immediate aftermath of the 2011 Egyptian revolution was an exceptionally open time to be wandering around religious institutions in Cairo asking questions. I have only returned to Egypt for fieldwork once since the 2013 regime change (in April 2019) because I fear it is no longer safe to study Islamism with the methods I’m describing here. I wish I could have spent longer in Cairo, but extended field excursions are for the childless or the well-to-do, and I was neither. Grants from various sources covered my travel, but not my family’s, so I went alone and kept it short. If, like me, you have constraints that make long stays impossible, take several short trips to the field and try to make every moment count.

5. Richard A. Nielsen, Deadly Clerics: Blocked Ambition and the Paths to Jihad (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

7. Max Perry Mueller, Race and the Making of the Mormon People (Chapel Hill, N.C.: UNC Press Books, 2017).

8. Lee Ann Fujii, “Five Stories of Accidental Ethnography: Turning Unplanned Moments in the Field Into Data,” Qualitative Research 15, no. 4 (2015): 525–39.

9. For a meditation on the role of serendipity in research, see Timothy Pachirat, Among Wolves: Ethnography and the Immersive Study of Power (New York: Routledge, 2017), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203701102.