5

The Early Hellenistic Period: Turning Inwards

During coverage of the military campaign in Afghanistan against al-Qaeda and the Taliban, occasional news reports surfaced about ethnic minorities in that country, clans and whole communities, who claimed descent from the armies of Alexander III, “the Great,” king of Macedon. Whether or not those particular claims can be verified, it is true that Alexander in the course of his invasion and conquest of Persia founded numerous cities named after himself in which he may have settled a total of more than 36,000 garrison troops and disabled veterans (Griffith 1935: 21–5; Walbank 1981: 43–5). The most noteworthy of these was Alexandria on the Nile delta, later the capital of Egypt under the Ptolemaic dynasty. Many of the others were located east of the Tigris; several remote “Alexandrias” preserved elements of Greek civilization for a long time after their founder’s death.1 Although the degree of Hellenic and indigenous cultural interaction may not have been as large as was once supposed (Green 1990: 312–35), in these enclaves the local nobility at least had the opportunity to develop familiarity with the Greek language and the characteristic Greek civic institution, the gymnasium. Lured by the economic possibilities of exploiting native resources, Greek merchants and traders were meanwhile drawn to those areas in increasing numbers, and a regularized form of Greek, the koinê or “common” dialect, was widely spoken and used in record-keeping and commerce. To this extent we can still speak of the “Hellenization” of what had been the Persian empire.

The Persian expedition was the result of a radical alteration in the balance of power among the formerly independent Greek city-states. In 360/59 BCE Alexander’s father, Philip II, succeeded to the kingship of Macedon following the death of his elder brother in battle. Situated north of Thessaly and bordering the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea (see Map 1), Macedon was a small mountainous kingdom on the periphery of the Hellenic world, continuously under threat of invasion from surrounding tribes. After restructuring the citizen army and pacifying neighboring territories through subjugation or alliance, Philip turned his ambitious eyes south and soon became the dominant player on the mainland Greek political scene. Macedon had long been entangled in Greek political affairs and open to Greek cultural influences; its royal house, the Argeads, claimed descent from Heracles and ties to Argos in the Peloponnesus (Hdt. 8.137–39). Those pretensions to Hellenic ethnicity were bitterly contested, however, after Philip began his struggle with Athens and her allies over control of southern Greece.2 His definitive military victory at Chaeronea in 338 BCE against a coalition led by Athens and Thebes put the Greek peninsula under Macedonian rule, ending the autonomy of the poleis.

As hegemôn, or leader, of a newly formed League of Corinth made up of the states he had defeated, Philip announced his plans to attack Persia but was assassinated in 336 before he could implement them. Alexander inherited both Philip’s crown and his undertaking. After harshly putting down rebellion in Greece, he crossed into Asia two years later at the head of the Macedonian army, never to return. Successive operations took him from the Near East to Egypt, then across the Middle East and central Asia – the full breadth of the Persian Empire – into India, whereupon his troops refused to progress further. Having retraced his journey to Babylon, the Persian capital, he may have been planning a Mediterranean campaign against Carthage (Diod. Sic. 18.4.4) when he died there in 323 BCE.

In the wake of Alexander’s death and the ensuing power struggles of his generals, the Successors, a cultural transformation took place: Greece entered the so-called Hellenistic Age, a period lasting until the death in 30 BCE of the final descendant of the Macedonian ruling dynasties, Cleopatra VII of Egypt. For most of the following century, Athens, once the proud leader of an empire, was under the control of one or another Macedonian dynast, with Macedonian troops billeted in the port area to keep order. Although the people agitated for restoration of democratic rule, the local Athenian oligarchy, in collaboration with its royal masters, maintained a tight grip on both the financial and political systems. Ordinary Athenians were effectively disenfranchised. This does not mean that participation in civic life ceased altogether, but it must have been diminished. Some people redirected their energies toward achieving material success in this age of expanding economic markets; others turned to philosophy for peace of mind. We see a rising emphasis on individualism and one’s ethical obligations to oneself.

In mainland Greece certain defining characteristics of the Hellenistic era had already emerged early in the fourth century. Extensive rural poverty resulted from the Peloponnesian War and ongoing quarrels among the Greek city-states. When plantations of slow-maturing vines and olives were destroyed by invading troops, marginal landholders could no longer support themselves; they lost their farms and drifted to urban areas or enlisted as itinerant mercenaries. Wars and internal power struggles also created great numbers of exiles throughout the Greek world, including Italy and Sicily as well as the mainland (McKechnie 1989: 34–78). The political theorist Isocrates pictures a substantial population of rootless and displaced persons wandering around Greece at this time (4.133, 167–9; 5.96, 120–2; 8.24); his accounts may be inflated for rhetorical purposes, but he does call attention to a rising problem (Billows 2003: 197–8). Wealth was concentrated in the hands of fewer individuals; except in some relatively prosperous poleis where paid work could be had, tensions between rich and poor became more pronounced.

As a remedy for economic and social distress, Isocrates in a long series of letters and speeches urged first Athens and Sparta and afterward, as Macedon’s prominence rose, king Philip himself to mount a campaign against the Greeks’ common foe Darius III, the Great King of Persia, in order to acquire the massive wealth of the East for themselves. This “Panhellenic” crusade, justified as revenge for the Persian invasion of Greece and liberation for the Ionian cities still subject to a barbarian overlord (Isoc. 4.182–5), was in reality driven by the anxieties of the property-owning class wanting to rid themselves of the troublesome poor by packing them off as mercenaries. Philip, for his part, used the same Panhellenic propaganda to justify the forced collaboration of the southern Greek states in a war of aggression under his leadership (Pownall 2007: 24–5). Historical analogies between past and present incursions of a Western superpower into the same geographic regions of Mesopotamia and Central Asia can be easily drawn and prove illuminating (Romm 2007).

Alexander’s military expedition permanently altered the political and cultural features of the land now known as the Middle East, but its consequences for Greeks left at home were even more far-reaching. As geographic and social mobility increased, older forms of social cohesion broke down, fragmenting kinship ties. Citizen males who had emigrated or become professional soldiers often did not return to their own home towns to marry and have children but instead settled and raised families elsewhere. Tombs and ancestor cult might therefore be abandoned.3 While the population of major urban centers grew substantially during the Hellenistic era, numbers of persons with citizen rights who were eligible to own land in rural districts apparently fell. In Sparta that problem was especially troubling, for Aristotle ascribes the military weakness of the Spartan state in his day to a lack of manpower, which had slipped below 1,000 male citizens (Pol. 1270a.29–34). Such shifts in patterns of settlement had a long-term impact on local agricultural economies. In the second century BCE the historian Polybius complains of a grave population crisis (36.17.5): “Childlessness and a general shortage of people have gripped all Greece in our own times, so that cities have been left desolate and destitution has occurred, even though ongoing wars and recurrent plagues have not befallen us.” Later authorities, Greek and Roman, continue to describe Greece in comparable terms: the theme of a formerly great nation in decline and ruin becomes a moralizing cliché. Archaeological surveys of select rural environments do suggest a decrease in actual numbers of inhabitants beginning in the late Hellenistic period and continuing under Roman administration, though it seems less catastrophic than the literary sources attest (Alcock 1993: 33–92; cf. Reger 2003: 334–5).

More positive social developments, though, came to pass later in the Hellenistic period after the Successor kingdoms were established. Cities were still subject to far-reaching geopolitical pressures, but, with large-scale instability reduced, local forms of civic life took on renewed importance. Democracy became the accepted mode of government for the majority of Hellenistic cities; inscriptions indicate a substantial amount of electoral participation (Gruen 1993: 354). Even under monarchical oversight, elected or appointed magistrates and public assemblies were kept busy addressing matters of community interest and providing more elaborate amenities and services for the population. To facilitate these improvements, cities turned to native benefactors for political and financial support, acknowledging their assistance with public honors. Such expressions of communal gratitude defused resentment at the economic gap between rich and poor. “[T]he interaction between citizen assemblies, civic magistracies and the wealthy elites in taking care of the cities’ infrastructures and needs showed that civic morale and public spirit remained high despite the reduced independence of the Greek cities in the new world of Hellenistic Empires” (Billows 2003: 209–12; quotation from p. 212). The great age of Hellenistic urban culture, centered upon the gymnasium, the training of ephebes, and the local festival, was now under way.

All these historical occurrences had enormous practical consequences for women. In some areas, declining numbers of men left poor girls without husbands and brothers unprotected and vulnerable physically and economically. Female-headed families of tenant farmers could not cultivate the land, as plowing demanded a man’s strength. If women were compelled to work outside the home, only a few respectable professions were open: midwifery (though it required a capital outlay for equipment), wet-nursing, weaving, and selling vegetables from a market garden. Most, probably, turned to prostitution. Wealthier women, on the other hand, benefited financially from the loss of male kin, since they alone might be left as heirs. In the chapter of the Politics cited above, Aristotle notes that currently two-fifths of Spartan land was in the hands of women. Increased economic power, in turn, could bring with it increased religious and even municipal responsibilities. Rich women gained greater visibility by serving first as public priestesses and then, starting in the late Hellenistic period, as honorary magistrates for their cities. During their terms of office, they donated buildings and sponsored civic events; in thus putting their resources back into the community, they purchased prestige and gratitude for themselves and their kin (Kron 1996: 171–81; van Bremen 1996: 11–40).

Because, as Polybius tells us, even affluent families had begun to have fewer children, daughters were more highly valued than before. Those families who could afford it paid to have their girls educated. Terracotta figurines produced for middle-class consumers in Egyptian Alexandria include representations of young girls reading (Pomeroy 1984: 60 and plate 7). Starting in the fourth century, growing numbers of females moved into the liberal arts and professions: women became physicians (IG II2 6873), painters, and writers (Pomeroy 1977). By the end of that century, female poets were starting to exercise artistic influence upon male authors. Under the patronage of the Ptolemaic queens Arsinoë II and Berenice II, writers in residence at the royal court in Egypt composed works featuring psychologically credible renderings of women’s subjectivity.

Improvement in women’s status coincided with a more intense emphasis on private life. Despite the economic pressures that made it difficult for the less well-off to support a family, the institution of marriage itself assumed new importance: it was now considered a primary source of emotional satisfaction for the individual as well as a strategy for family continuity. At Athens, the New Comedy of Menander and his contemporaries responded to this change in attitudes with sentimental dramatic scenarios defending romantic love as a motive for choosing a mate. Plutarch accordingly pronounces Menander’s plays appropriate after-dinner entertainment for husbands soon to join their wives at home: they contain no pederasty; girls who lose their virginity are in due course properly married; wicked hetairai are punished and good hetairai rewarded (Mor. 712e). Issues of sex and marriage are discussed at length in Plato’s last work, the Laws, and relationships of affection are a preoccupation of Aristotle’s ethical treatises. Whether the wise man ought to marry or even have sex was strenuously debated by adherents of Stoicism and Epicureanism, the two great philosophical schools of the later Hellenistic period. Other intellectual movements, such as neo-Pythagoreanism, promoted the educated woman’s capacity to offer her husband intellectual and emotional companionship and to direct the moral formation of her children. Factors contributing to the materialization of this more pronounced heterosexual ethos, besides the economic and political causes mentioned above, may include medical and scientific considerations, the moral authority of Plato and other political thinkers, and innovative trends in artwork and literature produced in settlements outside mainland Greece. We explore some of those influences in this, and the following, chapter.

Court Intrigues

Before we consider tendencies affecting the wider Greek population, though, let us turn back to Alexander’s intimate life. Interest in his campaigns prompted by Western military involvement in the areas he traversed was heightened by the release of Oliver Stone’s much-anticipated epic film Alexander in November 2004. In the wake of that production, over one hundred books directly relevant to Alexander were rushed into print (Cherry 2007: 306–7). Though ultimately not a box-office success in the United States, Stone’s film provoked considerable public comment before and after its release.4 While faithful in other ways to traditional epic cinematic conventions such as spectacle, it broke new ground by presenting its hero, in keeping with the historical record, as having partners of both sexes: by implication, his childhood friend and comrade Hephaestion and, unambiguously, the Persian eunuch Bagoas, along with the monarch’s three wives Roxane, Stateira, and Parysatis. Predictably, this “bisexual” portrayal was deeply offensive to social conservatives and to Greeks and Greek-Americans who looked upon Alexander’s exploits as a source of national pride (Paul 2007: 18; Solomon 2007: 43–4). Gay critics, on the other hand, complained that Stone had not gone far enough in his treatment of a hero who had long been a gay icon. His attachment to Hephaestion, for all its emotional intensity, is never given an overtly erotic coloring on-screen, prompting one dissatisfied viewer to dismiss the celluloid relationship as merely a male-bonding “bromance” (Nikoloutsos 2008).

Current scholarship postulates that Alexander’s sexual behavior, as far as the historical sources – all non-contemporary and often untrustworthy – allow us to draw legitimate conclusions about it, conformed to that of other male members of the Argead dynasty (Reames-Zimmerman 1999; Cartledge 2004: 228; Ogden 2009: 217). However, the customs of the royal house diverged somewhat from the Athenian protocols we have been examining. Although age-differential relationships were not unusual (Pausanias, the assassin of Philip II, was a former erômenos who bore the king a private grudge), erotic liaisons between age-mates are likewise attested, at least among the Royal Pages, a corps of elite adolescents who served as the king’s personal attendants (Curt. 8.6.2–10, Arr. 4.13.1–4; see also Ogden 1996: 119–23). Alexander and Hephaestion were coevals, raised together (Curt. 3.12.16). While none of the extant ancient biographers refers to Hephaestion as anything more than Alexander’s trusted companion,5 modern historians grant that the pair may have been lovers when young, though not necessarily as adults (but cf. Lane Fox 1974: 56–7, whose opinion Stone appears to accept when hinting at continued sexual relations). Whatever the truth, no one doubts the strength of their mutual love. Certainly Alexander’s extravagant grief at Hephaestion’s death, only eight months before his own, was perceived by many if not all ancient writers as excessive (Arr. 7.14.2–3), though some scholars observe that it did follow a normal bereavement pattern (Borza and Reames-Zimmerman 2000: 30; Reames-Zimmerman 2001). Calling attention to the similarity between their friendship and the bond of perfect philia Aristotle describes in the Nicomachean Ethics (1156b5–35), Reames-Zimmerman remarks that “[i]n terms of affectional attachment, Hephaistion – not any of Alexander’s three wives – was the king’s life partner” (1999: 92; italics are hers). Like Achilles and Patroclus, to whom ancient writers often compared them, Alexander and Hephaestion did not fit the pederastic model but were instead operating within their own set of cultural norms.

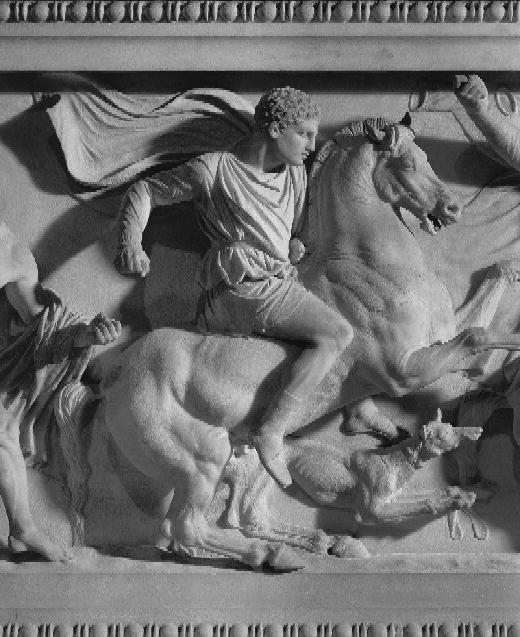

Family structure, too, was markedly different from the form it ordinarily took in classical Athens, for the Argeads practiced polygamy. In a famous passage from his lost Life of Philip, the biographer Satyrus (ap. Ath. 13.557b–e) lists the names and backgrounds of Philip’s seven wives – one more than Henry VIII (who, admittedly, is at a disadvantage, since he only engaged in serial monogamy). Satyrus leaves no doubt that these unions served a diplomatic purpose: Philip “married in accordance with his wars,” he remarks, citing the peoples each wedding was designed to conciliate. Alexander was born from the fifth of Philip’s wives, the Molossian princess Olympias, who also produced his full sister Cleopatra. The young prince grew up in the company of several half-siblings: two older sisters and an elder brother, Arrhidaeus, the latter mentally deficient (Plut. Alex. 77.5). With a view to his probable destiny, Alexander was given a truly outstanding education, receiving not only physical training in war, athletics, and hunting (fig. 5.1) but also an immersion in literature, in particular Homer, and the sciences, supervised by Aristotle himself. If anyone was prepared by his upbringing to be a king, Alexander was.

By its very nature, however, polygamy in combination with the absence of a fixed principle of legitimacy, also true of the Argead clan, invites strife whenever a regime change occurs (Mitchell 2007). Polygamous societies prioritize the availability of a capable heir (Carney 2000: 24–5). In Macedon the king was the war leader and border disputes were constant, so chances of death in battle were high (Ogden 1999: xvi). Moreover, regicide was surprisingly frequent (Carney 1983). The tendency, then, was to sire even more potential heirs than might be needed. When the ruler died, whether of natural causes or not, eligible sons, along with uncles and cousins, attempted to seize the throne, competing with half-brothers by other wives. Mothers had strong motives for ensuring a child’s succession, since they would enjoy more power as queen mothers than they had as mere queens (Greenwalt 1989). Among the Argeads, therefore, violent and lethal family disputes were the rule. Though he had treated Alexander as heir apparent, Philip’s final marriage to a native Macedonian woman, another Cleopatra, raised hopes for a successor of pure Macedonian blood. When the bride’s uncle and guardian Attalus drunkenly voiced that sentiment at the wedding feast, Alexander threw a goblet at him; in consequence he and Olympias briefly fled into exile (Plut. Alex. 9.3–5). After Philip was killed, rumors arose that Olympias and perhaps Alexander too were complicit (Plut. Alex. 10.4, Just. Epit. 9.7.1–2). One present-day historian has actually made a hypothetical case for parricide (Cartledge 2004: 92–6). Olympias herself is also accused of engineering the deaths of the widowed Cleopatra and her infant daughter (Just. Epit. 9.7.12; Paus. 8.7.7). That Alexander, in order to strengthen his position, quickly executed certain prominent nobles on the grounds of conspiracy, among them Attalus and, just to be safe, his own cousin Amyntas, is undisputed.

As noted above, Alexander too was polygamous, taking three wives, again for obvious political reasons. None were Macedonians. His alliance in 327 BCE with Roxane, daughter of a Bactrian chieftain, earned him the goodwill of previously hostile local nobles (Carney 2000: 105–7). In 324, during an elaborate mass wedding ceremony at Susa, he married two women from separate branches of the Persian royal line: Stateira, eldest daughter of Darius III, and Parysatis, youngest daughter of Darius’ predecessor Artaxerxes. This dual union strengthened his claim to legitimate rule of Persia. Although he postponed marrying until he was almost thirty, Alexander did have an earlier longstanding relationship with the young foreign widow Barsine, who is unaccountably given no part in Stone’s film.6 Product of a mixed marriage between a Persian satrap and the sister of Greek mercenaries, Barsine had probably known Alexander since childhood, for her family was then living in exile at Philip’s court; their affair began, however, only after she, together with other female members of the Persian nobility including Darius’ mother, wife, and daughters, was captured at Damascus in 333 BCE following the battle of Issus (Plut. Alex. 21.4, Eum. 1.3). The liaison lasted approximately five years, producing one son, Heracles, named after the reputed ancestor of the Argead line. Though technically having no formal connection with the king, Barsine appears to have enjoyed considerable prestige behind the scenes, since at the mass marriage ceremony in Susa Alexander bestowed two of her sisters and her daughter by a prior marriage upon favored officers (Carney 2000: 103–4).

After Alexander’s unexpected illness and demise7 an ongoing succession crisis lasting decades generated further rounds of bloodshed. Though several months pregnant with the future Alexander IV, a jealous Roxane is alleged (Plut. Alex. 77.4) to have personally slain her co-wives Stateira and Parysatis (Plutarch mistakenly terms the latter Stateira’s sister) and thrown their bodies down a well. This was supposedly done with the help of Perdiccas, one of Alexander’s marshals, who was acting as her guardian; given her condition, it seems more likely that Perdiccas himself, perhaps in collaboration with one or more fellow generals, eliminated the two Persian women in order to clear the way for Roxane’s child, the future Alexander IV. Five years later civil war in Macedon resulted in the brutal deaths of Alexander’s mentally incompetent brother Arrhidaeus, who as Philip III officially shared his monarchy with the toddler, and Arrhidaeus’ wife Adea Eurydice. Joint kingship of two legal minors was an invitation to anarchy. Fearing the future extinction of the dynasty, females from separate branches of the Argead line marshaled armies on behalf of the contender each supported: the matriarch Olympias, who had previously retired to her native Molossia, invaded Macedon to seek sole rule for her grandson, while Eurydice led out troops to defend her husband’s claim. War between two women was unprecedented (Duris of Samos ap. Ath. 13.560F). Before battle could be joined, however, the Macedonian army went over to Olympias’ side, refusing to fight against Alexander’s mother (Just. Epit. 14.5.1–2, 8–10). After they fell into her hands, Olympias first imprisoned and killed Arrhidaeus and then forced Adea Eurydice to commit suicide (Diod. Sic. 19.11.5). Olympias herself was soon afterward condemned and executed by Eurydice’s former ally Cassander, who emerged as de facto ruler of Macedon. Under his orders, Alexander IV and his mother were kept in custody until the boy entered his teenage years, when public opinion began to favor his assumption of the throne; at that point Cassander had Alexander and his mother quietly disposed of (Diod. Sic. 19.105.2–3). A little later (on the chronology, Wheatley 1988: 19 and n. 29), the last possible pretender to the succession, Barsine’s son Heracles, was put forward as a candidate, then publicly slain. That was the end of the Argead line.

The moral of the story is that winning an empire is one thing, passing it on another. This lesson too may have contemporary applications.

Who Is Buried in Philip’s Tomb?

In 1976 a leading Greek archaeologist, Manolis Andronikos, began excavating a large tumulus near the site of the ancient Macedonian palace at Argae, not far from the modern village of Vergina in northern Greece. During the next two seasons he discovered three fourth-century BCE tombs beneath the mound. Though the earliest, Tomb I, had been robbed in antiquity, a masterful wall painting survives showing Hades’ abduction of Persephone, monumental testimony to the shock of sudden death. Nothing else was left apart from pot shards, two broken pieces of a woman’s toilet set, and numerous bones, later identified as those of a man, a young woman, and a neonate. All had been inhumed, not cremated (Andronikos 1984: 86–95). Miraculously, the other tombs were intact. Rich grave goods placed in them, including furniture, weapons, and silver and bronze vessels, marked them as royal burials. Tomb II was divided into an antechamber and a main chamber, both containing cremated remains. In the main chamber, investigators found a gold casket, decorated on its lid with a sixteen-point star, the regal symbol that has since become known as the “Star of Vergina.” Inside were an exquisite gold wreath and the burned bones of a middle-aged male wrapped in what had been a purple cloth. The antechamber held a second casket, also containing a wreath, together with the bones of a young woman in a much poorer state of preservation (ibid., 97–197). Tomb III held the cremated bones of an adolescent male placed in a silver hydria crowned with a gold oak wreath. From the outset, the excavator insisted that the occupants of Tomb II were Philip II and one of his wives (Andronikos 1984: 226–31). Taken up enthusiastically by his patriotic Greek countrymen, that suggestion launched a controversy that continues to this day.

Because we know the names of all the royal Argead males who died during this period, we can arrive at one, and only one, alternative pair of candidates for the burials in Tomb II: Philip III Arrhidaeus and his wife Adea Eurydice. As stated above, they were killed by Olympias in 317 BCE (Diod. Sic. 19.11.5) and presumably interred hastily. Cassander, however, later cremated their remains and reburied them, according to royal custom, at Argae. Though a non-Argead, he was soon to marry Thessalonicê, daughter of Philip II and half-sister of Alexander, and was “already acting like a king in regard to the affairs of the realm” (Diod. Sic. 19.52.1, 5). Arranging an elaborate funeral for his predecessor would strengthen his own claim to the throne. This explains the presence of so many valuables, especially armor, heaped in the burial chambers. Similarly, Cassander would have been responsible for the interment of the last legitimate member of the Argead line, Alexander IV, son of Alexander by Roxane, who, it is generally agreed, is the youth buried in Tomb III. Even if he had murdered the boy in cold blood, Cassander would not have neglected the final rites: a dead Alexander was more valuable to him as propaganda than a living one (cf., though, Gattinoni 2010).

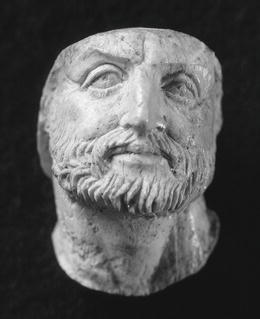

So who is buried in Philip’s tomb? Arguments based on the stylistic features of the structure itself, the painted frieze of an animal hunt over the doorway, and the archaeological finds within strongly point toward a date after Alexander the Great’s Eastern campaigns (Borza 1990: 261–2, Borza and Palagia 2007) but have not convinced everyone. Resolving the case may depend upon CSI-style labwork on the bone evidence. Cremation, even in present-day mortuaries, does not reduce bone; the ashes we scatter under a tree or across a golf course are the product of subsequent pulverization. In the case of the male Tomb II occupant, enough skeletal material has survived to permit forensic experts to draw conclusions, above all from the skull. We know that Philip II suffered an arrow injury to his right eye, leaving it blind. Several small carved ivory portrait heads, decorations from a couch, were found in the tomb; one is almost certainly a representation of Alexander III, while another shows an older man, bearded, whose right eye appears scarred (fig. 2). With this information in mind, specialists examined the bones of the skull and found irregularities above the right eye socket and on the right cheekbone that they attributed to severe trauma. Using facial-restoration techniques, they created a wax cast of a reconstructed head with mutilated eye that, when hair and beard were in place, looked amazingly like the ivory figure and also resembled supposed coin likenesses and busts of Philip (Musgrave, Neave, and Prag 1984; see further Prag 1990).

However, this accomplishment, impressive as it may seem, has been challenged. Another pathologist has now employed macrophotography to arrive at an opposite set of conclusions: the irregularities thought to be caused by trauma are either natural formations or effects of the cremation process along with inaccuracies in reassembling the skull. Examination of the rest of the skeletal material turned up no evidence of other wounds, despite ancient testimony to several more battlefield injuries. Finally, different outcomes occur when bones covered by flesh are cremated, as opposed to dry or degreased bones whose flesh has already decomposed. Long bones cremated dry, according to this report,

Contraction of bone collagen at high temperatures accounts for the peculiar changes in flesh-covered bones. The bones of the Tomb II skeleton, light brown and minimally warped, with straight transverse cracking, are consistent with a dry cremation. These data fit the burial profile of Arrhidaeus, not that of Philip II. Most Anglo-American authorities on Philip and Alexander now believe that the man buried in Tomb II was Alexander’s half-brother.

That conclusion does not exhaust the puzzles presented by Andronikos’s finds. Viewed through the lens of gender, the grave goods accompanying the woman buried in the antechamber are unusual (Carney 1991: 21). Apart from two items, there was no elaborate jewelry of the sort ordinarily found in a female interment. The gold wreath in the casket indicates that its possessor was a queen (Adams 1980: 70). There was also a gold pin with a chain knotted around it; the pin is foreign, of a type associated with the Illyrians, a tribal population west of Macedon. Instead of other objects of adornment, set against the sealed door to the main chamber (and thus placed there following the male burial) was a collection of armor, including a pectoral or breastplate, ceremonial greaves, and an embossed gold cover for a gorytos, a flat Scythian-style quiver. Weapons such as spears were likewise present. While the armor and weapons might have belonged to the male, ancient sources tell us that Cynna or Cynane, daughter of Philip II by an Illyrian wife, had been trained in the use of arms by her mother, for Illyrian women joined battle alongside men. She in turn trained her daughter Adea Eurydice, Philip’s granddaughter (Polyaen. Strat. 8.60; Duris of Samos ap. Ath. 13.560F; see Carney 2000: 128–31). Though her husband Philip III Arrhidaeus was nominally in charge of the Macedonian army, it was Eurydice who organized resistance against Olympias and her invading Epirote forces (Diod. Sic. 19.11.1–2). After Eurydice was captured, she showed great bravery. Ordered to commit suicide by Olympias and given a choice of a sword, a noose, or hemlock, she first laid out and cleansed the body of her murdered husband, then hanged herself with her own girdle, “neither weeping at her own fate nor crushed by the magnitude of her misfortunes,” as Diodorus observes (ibid., 7). If the military equipment belonged to her, its presence might indicate that her role as a military leader was being commemorated (Carney 1991: 25; cf. Palagia 2000: 191). While her husband, as king, received the more elaborate burial, she would have been honored for her own part in attempting to defend Macedon.

As for the whereabouts of Philip II, those who assign Tomb II to Arrhidaeus surmise that by process of elimination the osteological remains in the looted Tomb I could be those of Alexander’s father, his youngest wife Cleopatra, and their infant daughter (Carney 1992; Borza and Palagia 2007: 82–3, 118; Gattinoni 2010: 115). The historical account supports that possibility, but more labwork may be needed to confirm it.

Medicine and the Sexes

During the late archaic age a number of thinkers in Greek settlements on the Western coast of Asia Minor and in southern Italy and Sicily began to speculate on the composition of the physical universe and to find rational explanations for natural phenomena such as eclipses. Out of this pre-Socratic investigative movement there evolved a theoretical understanding of the human body as made up of various opposing forces that must be kept in equilibrium (Nutton 2004: 44–50; MacFarlane 2010: 46–51). Disease, according to Alcmaeon of Croton (Kirk-Raven-Schofield 1983: 260 and fr. 310; see Nutton 2004: 47–8 and Holmes 2010: 99–101) arises from some disproportion (extreme heat or cold, excess or deficiency of nourishment) and may be triggered by the impact of external factors on the blood, marrow, and brain. By the late fifth century, medical writers could speak of four bodily fluids or “humors” – blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm – whose balance and mixture varied with the seasons ([Hippoc.] Nat. Hom. 4–7) but could be regulated through diet and treatment. For men in the prime of life sexual activity played a part in maintaining health by drying the body through discharge of surplus moisture; this is why, despite its potential risks, it was thought medically necessary.

Sex was vital for women, too, but for quite different reasons. Hesiod’s idea that “women are wet,” i.e., that their flesh stores up more liquid than a man’s, became the basis of the Hippocratic model of female gynecology. While the so-called “Hippocratic corpus” of Greek medical texts – a collection of sixty to seventy treatises credited to the historical physician Hippocrates of Cos but probably composed by other anonymous, mostly fifth- and fourth-century, practitioners – sometimes disagrees on the causes and treatments of disease, its basic construction of the female body is consistent, owing much, conceptually, to the myth of Pandora (King 1998: 21, 23–39). Hippocratic writings contain many case histories of male illness, but there was no cluster of diseases recognized during the classical era as specific to men. In contrast, no fewer than ten gynecological treatises address the peculiar health problems of women. Women’s pathology is inevitably ascribed to difficulties occurring in the reproductive system (“wombs are the cause of all diseases,” [Hippoc.] Loc. Hom. 47.1), and the surviving texts reflect a high degree of medical anxiety over a woman’s capacity to reproduce. Thus men are regarded as the physiological norm, the subject of “general medicine,” while women, with their unique bodily organs, constitute a special case (Dean-Jones 1994: 110–12).

In these medical texts women’s physiology is so distinct from that of men that they might well be considered a separate race; because of their biological makeup, furthermore, they are at the mercy of their sexual drives in a way that men are not. Anatomically, the distinguishing feature of the female is the hodos, an uninterrupted internal passageway extending from nose and mouth to vagina.8 Scent therapies applied to the nostrils could therefore affect organs in the lower parts of the body. Woman’s flesh too is of a completely different texture, spongy and absorbent, like wool ([Hippoc.] Mul. 1.1). The excess moisture she extracts from food, stored as blood, must be regularly evacuated during the menstrual period or consumed by the fetus in pregnancy; otherwise death can result. The short treatise On the Diseases of Unmarried Girls (8.466–70 Littré) warns that virgins are prone to mental illness and suicide if menarche is delayed, for the blood accumulating in their bodies can put pressure on the heart and diaphragm, where consciousness was thought to reside. The only cure is marriage and pregnancy (King 1998: 77–9). The womb or gastêr, which the Hippocratics compared to an inverted storage jar, was also a source of female troubles. Because it collected blood to be expelled in menstruation or used to nourish the child, it was unusually susceptible to dryness. It was believed to be an independent organ unattached to the body, and could therefore leave its proper place to travel up the hodos searching for moisture, rising to the lungs and neck and producing suffocation ([Hippoc.] Mul. 1.7; Loc. Hom. 47.1–4). Intercourse, however, irrigated the womb, heated the blood, and made the menses flow more easily. To preserve their health, then, women too needed sex, but unlike men were allowed it only in marriage. The fact that medical writers speak of female sexual experience exclusively in terms of heterosexual penetration suggests a certain societal indifference to any non-reproductive genital activity.

In the Timaeus (91b–c), Plato’s spokesman characterizes the reproductive organs of male and female alike as autonomous, disobedient animals. The penis, goaded by lust, attempts to master (kratein) all things, a decided association of penetration with dominance. Conversely, the womb, “a living creature hungering to create a child,” begins wandering through the body if left fallow too long. Although he attributes wandering-womb syndrome to barrenness, not dryness, Plato is following Hippocratic tenets when he represents sexual appetite as a physiological compulsion arising from the organs themselves. Originating in similar fashion, the physical drive in each sex nevertheless pursues distinct goals: the man’s impulse to ejaculate is activated by the sight or mental image of an external object, but the woman’s craving for pregnancy is a response to her own internal void and the sexual act only a means of relieving that condition. Men could therefore exercise self-mastery by avoiding whatever might stimulate desire; women could not (Dean-Jones 1992: 76–80).

Although Hippocratic medicine considered the physical constitution of the sexes wholly dissimilar, male and female were assigned comparable functions in the reproductive process. Both partners, the author of On Generation asserts, produce “male” and “female,” that is, strong and weak, sperm during the sex act. These mingle in the womb. The sex of the child depends upon the strength or weakness of the sperm prevailing in quantity ([Hippoc.] Genit. 6), and inherited characteristics are also determined by the respective amounts of sperm contributed by father and mother (Genit. 8). That hypothesis, which explains why children may not resemble the same-sex parent, also allows for the positioning of gender attributes along a continuum, so that, depending on the potency of the sperm, some biological females will tend toward the masculine, or vice versa (King 1998: 9).

Popular conviction, however, denied the mother a share in the child’s heredity: like a farmer sowing seed in a field, a man was instead thought to plant sperm in the woman who served as its passive receptacle, a parallel that would readily occur to an agricultural society (Pomeroy 1975: 65). Feminist classical scholars cheerfully refer to this belief as the “flowerpot theory.” With the argument that the mother plays no active part in generation, Apollo in Aeschylus’ Eumenides successfully defends his client Orestes against a charge of matricide (658–61):

The so-called mother of the child is not its parent,

but rather the nurse of the newly-sown embryo.

The male who mounts begets. She, like a stranger for a stranger,

preserves the shoot, should the god not harm it.

Fantastic as this assumption may seem, it answered a nagging male fear that woman, who possesses a uterus to house the embryo and can nourish it herself, might also be able to conceive from her own seed without the help of a father (Hanson 1992: 41–3; Dean-Jones 1994: 148–52).9

Starting from different premises a century later, Aristotle arrived at a diametrically opposite conclusion: the male possesses the principle of generation, the female that of matter (Gen. an. 716a.5–23). Female menstrual fluid, he posited, is a discharge corresponding to semen in males. Both manifest for the first time at puberty, and both are a residue of the normal blood produced by nutriment. Sperm is the vehicle through which the human form is transferred from a living being to inert matter. There is no such thing as female sperm, however, because the production of two discharges at the same time would be a redundancy: “for if there were sperm, there would be no menstrual secretion, but as it is, the existence of the latter indicates that the former does not exist” (Gen. an. 727a.29–30). During ejaculation, blood stored in the passages around the testes is concocted, or condensed, into a more potent liquid. Females are colder than males and do not have the vital heat required to manufacture sperm, which is capable of activating matter only when hot and thickened. Hence the mother does not play an active part in conception, but instead contributes matter, in the form of menstrual blood (which, being a residue, is itself richer than ordinary blood), to nourish the resulting embryo.

If women’s role in the reproductive process is circumscribed, however, it is precisely because in other ways she has been more closely assimilated to the opposite sex. For Aristotle, woman was a human being, although less perfectly formed than man: famously, he states she is “a defective male, as it were” (Gen. an. 737a.28). In so far as her lesser body heat requires her to perform a complementary but different biological function, she must develop complementary but different reproductive organs – the uterus, corresponding to the male penis and testicles. There is, moreover, a formal resemblance between each set of parts, for the uterus, Aristotle adds, has a double chamber, just as the testicles are twofold (Gen. an. 716b.32–3). This notion of functionally corresponding male and female sexual organs made a decisive impact on later medical theory. Although we do not know whether Aristotle’s views were shaped by changes in the societal position of Greek women, acceptance of his model of female biology has plausibly been linked to contemporary expansion of their communal, legal, and economic activities (Dean-Jones 1994: 20, 249–50).

Subsequently, Hellenistic doctors resident at Alexandria were able to practice dissection and observe the internal features of the human body. Their most important representative, Herophilus, affirmed that the uterus is substantially the same as other organs and denied the existence of conditions specific to women other than those directly concerned with reproduction (Sor. Gyn. 3.3). Under the Roman empire, this line of thinking was pursued to its logical end, the “one-sex” model of human physiology in which the reproductive organs were seen as essentially the same, differing only in their internal or external positioning. Galen, the great second-century CE physician, asks his readers to imagine the male parts turned inside out and placed inside the body, and the converse for the female parts. The scrotum, he claims, would take the place of the uterus, the penis the vagina; meanwhile, the uterus, turned outward, would contain the ovaries in the manner of a scrotum, and the cervix would become the male member. Like the eyes of a mole, which exist in the animal but cannot open, the female organs, already formed within the fetus, are not able to emerge and project outward due to lack of vital heat (UP 14.6). While this is an imperfection in the woman, he concludes, it is perfect for human reproduction, since it provides a safe place for gestation. Preserved by Byzantine and Arab physicians, Galen’s treatises were handed down to students of medicine in Renaissance and early modern Europe. Until well into the eighteenth century, his anatomical model remained the standard paradigm for Western medicine, not only consulted for diagnosis and treatment but also controlling cultural assumptions about gender (Laqueur 1990: 4–8).

For women, the displacement of the Hippocratic paradigm of “otherness” had both good and bad consequences. Females were no longer treated as a special class of patients whose health was linked entirely to the proper functioning of their reproductive organs. For therapeutic reasons, this development was patently desirable. While regarded as comparable in physical makeup, however, women were perceived as fundamentally inferior to men because of their lesser body heat. At the same time, those aspects of their physiology that were distinctive, like menstruation, began to be seen as insalubrious or disgusting. Herophilus questioned the usefulness of menstruation; by the second century CE, Soranus, a Greek doctor practicing in Imperial Rome, could insist that it actually endangered female health (Gyn. 1.29).

On the whole, though, this revolution in medical theory improved women’s status because it acknowledged their capacity for self-discipline. Tragic heroines might struggle against Aphrodite’s urges, but Hippocratic physicians would consider such efforts doomed from the outset. Woman could not restrain her appetite for intercourse, as it was incited by physiological necessity, so much so that abstinence did her harm. This construction of female desire buttressed the social practice of subordinating women to male authority and rigorously supervising them during their reproductive years. Aristotle’s belief in the analogous structure of male and female bodies led him to think in terms of comparable sexual appetites, which in each sex could be regulated through the exercise of self-control, even though woman’s innate ability to act as a moral agent was inferior (Dean-Jones 1992: 86). Once it was commonly admitted that women were capable of saying “no,” they were allowed more freedom to move beyond the oikos and come into contact with strangers.

From Croton to Crete

Theseus’ son Hippolytus is an anomaly. No archaic or classical Greek thinker seems to have advocated complete abstinence from sex as a way of life.10 Strict monogamy, for husband as well as wife, was a different matter: the late sixth-century sage Pythagoras of Samos, who migrated to southern Italy and headed a religious foundation at Croton, imposed that regulation on his followers.11 Although he promulgated a doctrine of the transmigration of souls and laid down dietary rules similar to those of the Orphics, his remarks on sex as they have come down to us nevertheless do not reflect anxiety over carnal pollution but are instead dictated by commonplace Greek medical and ethical considerations. He is reported as saying that ta aphrodisia, though less harmful during the winter months, are not good for a man’s health and cause physical debility and that they also weaken self-mastery (Diog. Laert. 8.9, cf. Diod. Sic. 10.9.3–4). On a journey to the underworld Pythagoras allegedly saw men who had been unwilling to have intercourse with their wives undergoing chastisement (Diog. Laert. 8.21). This biographical fabrication (which sounds suspiciously like a fossilized joke from Attic comedy) touches upon the special place occupied by monogamous marriage in Pythagorean ethics.

In accounts of Pythagorean doctrine composed after Plato’s time, proponents are made to take a very hard line on sex. A late Hellenistic tract On the Nature of the Universe attributed (falsely) to the Pythagorean Occelus states unequivocally that intercourse was designed not for pleasure but procreation (4.1–2). Iamblichus’ On the Pythagorean Life (209–10) contains precepts against precocious sexual experience (for boys, not before the age of twenty) and against intercourse “contrary to nature and with outrage” (para physin… meth’ hybreôs), a reference to pederasty; sex instead should be undertaken “in accordance with nature and with sôphrosynê” in order to produce a child. The evidence is a mixed bag, and not all of it may be reliable, but the general picture it gives appears consistent: sex within marriage, conducted with restraint and a view to procreation, merits praise; extramarital sex of all kinds is forbidden.

Since Pythagorean thought enjoyed renewed popularity in the Hellenistic age, it may have encouraged growing support of marital fidelity as an ideal for men as well as women. The fourth-century orator Isocrates makes the Cypriot king Nicocles denounce spouses who “through their own indulgences wound those by whom they would not expect to be wounded, and, though they show themselves fair in all other transactions, do wrong in those involving their wives” (3.40). A late fourth-century treatise on household economics attributed to Aristotle, though probably composed by a student, follows Xenophon in its description of the respective work assignments of man and wife but structures the relationship according to Aristotelian hierarchical principles. When it stipulates the husband’s duty to his wife, however, it shows the influence of Pythagorean precepts ([Arist.] Oec. 1344a.9–12):

First, the rules in respect to the wife: let him do her no injury. For thus he himself will probably not be injured by her. Even the common law of humanity, as the Pythagoreans say, instructs us in this: one must avoid injuring a wife just as one would not harm the suppliant raised from the hearth. And the husband’s extramarital intercourse does her an injury.

This mandate invests fidelity to the marital bond with the sanctity and dignity of suppliant ties. If it is a relic of early Pythagoreanism, it may well reflect the stringent mores of the original fellowship at Croton in which all property was reportedly held in common and women participated on an equal footing with men.

Plato was familiar with Pythagorean doctrine, and its influence may arguably be detected in his injunctions about sex in his last work, the Laws, which was probably left unrevised at his death in 347 BCE. In such earlier dialogues as the Phaedrus and the Symposium, erôs is a catalyst impelling the lover to appreciation of the highest truths. Physical chastity is the prerequisite for this encounter with wisdom, but Plato is quite aware that human beings are weak. At Phaedrus 256b–d, Socrates envisions a couple, lovers of honor but not given to philosophy, who yield to desire in a moment of frailty and thereafter indulge in sex occasionally, though with misgivings. He pronounces their way of life less worthy, but admits that it still allows for some spiritual growth. In the Laws, though, Plato’s denunciation of homoerotic acts is sweeping, with no provision made for human shortcomings. His debt to Pythagoreanism is greater in his final dialogues (for example, Timaeus of Locri, his spokesman in the Timaeus, voices Pythagorean ideas on number and harmony), and the question, perhaps not fully resolvable, is whether his own stringent pronouncements are borrowed from Pythagoreanism or, alternatively, whether Platonic sexual ethics were instead projected retroactively on to the early Pythagoreans.12

In the first two books of the Laws, as we saw, the Athenian Stranger critiques the archaic pedagogical institutions of Crete and Sparta. Then he expounds on the lessons of history and the reasons for the breakdown of other political constitutions, including the collapse of Athenian democracy. At the conclusion of the third book, Cleinias, the Cretan, mentions that he is a member of a board of ten overseers charged with drawing up a legal code for a new colony that his countrymen are planning to found (702c–d). With a view to providing a framework for the actual code that Cleinias and his colleagues will eventually fashion, during the remainder of the conversation the three men attempt to formulate a constitution for an imaginary settlement, Magnesia, numbering precisely 5,040 households – a key Pythagorean number (737e). Keeping that background in mind, we can examine what is said about homoeroticism and the other modes of sexual behavior to be addressed in such legislation.

We have already encountered one attack on pederasty in the opening book of the Laws (636b–c), where the Athenian Stranger charges that the Cretan and Spartan customs of all-male dining and gymnastic exercise foster homoerotic relations. In contrast to procreative heterosexual relations, they produce pleasure “unnaturally” (para physin). Hence persons who perform these acts do so from inability to restrain their appetites, and, in doing so, they thwart the reproductive purpose of sex.13 This indictment of same-sex intercourse is intended to refute the suggestion that the characteristic military institutions in Sparta and Crete further temperance. As a civic virtue, temperance demands not only moderation in the use of legitimate pleasures but abstention from those that violate communal norms. Since homoerotic relations were an established part of Dorian culture, the Athenian must appeal to the higher law of nature to bolster his claim that debauchery is induced rather than prevented by the all-male ambience of common meals and gymnastic training. We recall Iamblichus’ report that sex “contrary to nature and with outrage” was prohibited by the Pythagoreans. Similarity of phrasing may point to Pythagorean influence here.

The lengthier of the two criticisms is part of a later disquisition on curbing licentiousness (835e–841d). The Stranger proposes a practical strategy for discouraging homoeroticism: mustering general public opinion against it by declaring it unholy and contrary to religion, just like incest. Grounded as it is on an appeal to physis, however, that prohibition would have to extend beyond same-sex relations to embrace other modes of non-reproductive sex (838e–839a):

This is just what I was getting at when I said I knew of a way to put into effect this law of ours which permits the sexual act only for its natural purpose, procreation, and forbids not only homosexual relations, in which the human race is deliberately murdered, but also the sowing of seeds on rocks and stone, where it will never take root and mature into a new individual; and we should also have to keep away from any female “soil” in which we’d be sorry to have the seed develop.

To understand the force of this precept, we must turn to a prior law – the very first, in fact, to be laid down. Marriage will be mandatory for all the adult male citizens of Magnesia (and, it goes without saying, for women too). The publicly stated justification is not perpetuation of the household, as one might expect, but self-continuance: producing children is the method provided by nature for the individual to share in immortality, and the man who deprives himself of that opportunity behaves in an unholy manner (721b–d). Since sex is designed for procreation, male–male intercourse is part of a blanket proscription that also rules out onanism and sex with female partners unfit to reproduce as contrary to its natural purpose (Price 1989: 231). In absolute fairness to Plato, though, limitation of sexual relations to reproductive ends seems to apply only until the couple has produced the requisite number of children (ideally two, one of each sex) or exceeded the prime age for reproduction (Gaca 2003: 53, 56–7). After that period, averaging about ten years per couple, discreet and moderate sexual activity for non-reproductive purposes is permissible (784e3–785a3). In no case, however, would homoerotic sex be tolerated.

All this is reminiscent of Pythagorean teaching on marriage.14 Concentration upon the reproductive purpose of sex is certainly in keeping with its principles. Sanctions against consorting with hetairai are attributed to Pythagoras, since we learn from Iamblichus that the inhabitants of Croton sent their mistresses away at his behest (VP 50, 132, 195). When the Athenian expresses hope that such a law, apart from discouraging adultery and dissipation, would lead men to be friendly and affectionate (oikeious kai philous, 839b.1) toward their wives, he also seems to be endorsing Pythagorean support for companionate marriage. Tellingly, Rist observes that this sentiment is “not a familiar theme in Plato” (1997: 76). Here, I think, the evidence of direct influence is very persuasive.

In concluding his discourse on sexual legislation, the lawgiver admits that the proposals he has put forth, though they would benefit any state if enacted, are highly visionary. Thus he ends by adopting a fallback position involving two options (841d–e):

However, God willing, perhaps we’ll succeed in imposing one or other of two standards of sexual conduct. (1) Ideally, no one will dare to have relations with any respectable citizen woman except his own wedded wife, or sow illegitimate and bastard seed in courtesans, or sterile seed in males in defiance of nature. (2) Alternatively, while suppressing sodomy entirely, we might insist that if a man does have intercourse with any woman (hired or procured in some other way) except the wife he wed in holy marriage with the blessing of the gods, he must do so without any other man or woman getting to know about it. If he fails to keep the affair secret, I think we’d be right to exclude him by law from the award of state honours, on the grounds that he’s no better than an alien.

The first and more preferable alternative would enforce strict sexual monogamy on all citizen males, prohibiting adultery and traffic with prostitutes as well as same-sex relations. The second ordinance makes allowances for surreptitious recourse to paid women at the risk of public shame if the perpetrator is found out. Homoerotic affairs appear to be excluded even if conducted in secret. As Moore (2005: 196) remarks, the second option, which anticipates that not everyone will be capable of complete self-control, “is potentially more suited to the real world of the second-best state.” In making this concession, the Athenian Stranger is still mindful of the reproductive function of sex, because extramarital affairs with female prostitutes can produce offspring, however unwelcome. Such affairs are not contrary to the natural purpose of the sexual act, as sterile same-sex activity would be. Introduced obliquely, as a stratagem for convincing the citizen body that homoerotic relations are improper, the objective of siring legitimate children and only legitimate children now assumes controlling importance for determining not only the moral quality of a sex act but also, when flagrantly transgressed, the civic standing of the man who has performed it. Belief that the state has a paramount interest in promoting lawful pregnancies while discouraging non-reproductive sex is also affirmed in a second passage of the Pythagorean treatise On the Nature of the Universe: “Those who have intercourse with absolutely no intent of creating children commit injustice against the most venerable institutions of society” (4.4). Whether Plato or Pythagoras took the first step, the line dividing the legislative assembly from the bedroom, and from the intentions of those in bed, has been crossed.

Even if the Greek text is occasionally unclear, Plato’s import is certain. His belief in erôs as a theoretical force for good does not appear to have changed. As he did in the Phaedrus, he draws a sharp distinction between feeling or affect toward another human being, which, if unselfish and governed by reason, can lead to virtue (837c), and carnal intercourse with its attendant, all too seductive pleasure. Genital acts between members of the same sex are wrong, he contends, because they afford gratification while impeding the procreative ends to which such pleasure has been attached as an inducement. Plato’s line of reasoning starts from the premise that in nature certain measures exist to bring about certain results. This teleological, or end-directed, conception of the material order logically assumes a divine arranger or demiurge that has rationally structured nature so as to fit ends to means. There is an obvious problem as to whether that notion of physis, with its latent teleological and theological import, can properly be mapped onto the scientific concept of an evolutionary process driven by the Darwinian principle of natural selection. To say, then, that Plato regarded same-sex intercourse (always carefully distinguished from affect) as “contrary to nature” is true enough, but it is a statement that first requires clarification of what the term “nature” means.

Safe Sex

Forced to deal with the momentous changes that transformed Greek society during the fourth and early third centuries, many educated men and a few women sought to develop emotional self-sufficiency through philosophic exercises. Facing threats of war and internal social unrest, instability of wealth and position, and an awareness of themselves as subject to the whims of the goddess Fortune (Tychê), they endeavored to form habits of mind enabling them to transcend pain and anxiety and attain private tranquility. Martha Nussbaum has conveniently labeled this enterprise a “therapy of desire,” since it adapted a medical model: “Philosophy heals human diseases, diseases produced by false beliefs” (1994: 14). Desire for any number of transient and manifestly unnecessary goods – wealth, power, success – was condemned as a source of mental disturbance, and the philosophic “patient” was taught to look upon such worldly things with indifference. “Living in accordance with nature” became the wise man’s aim. Again, much of the force of that precept depends upon the way in which the concept “nature,” physis, was interpreted. Cynicism, a radical movement that arose in the early fourth century, carried the directive to an extreme. Adopting a symbolic uniform of traveling cloak, staff, and knapsack containing all their possessions, its adherents stridently promoted asceticism, poverty, contempt for authority, rejection of the forms of civic life, and disdain for shame and social constraints, which they said inhibited natural instinct. The most notorious Cynic, Diogenes of Sinope, earned the movement its name by relieving his bodily urges with no more self-consciousness than a dog (kuôn), ostentatiously defecating and masturbating in public.

Throughout this period Athens maintained its prominence as a center of intellectual activity. Plato had set up the Academy, a “think-tank” for philosophy, and after his death it continued in operation under a long line of successors. Aristotle, who studied at the Academy as a young man, returned to Athens in 335 BCE from Macedon, where he had served as tutor to Alexander, to establish his own school, the Lyceum. Taking advantage of its extensive library, his students embarked on investigative fieldwork and wrote numerous descriptive treatises in the areas of natural history and political science. Both institutions were perceived as breeding grounds of pro-Macedonian sentiment, however; during a brief period of restored popular rule in 307 BCE an attempt was made to ban the establishment of new schools of philosophy, but it was soon revoked. By the beginning of the third century, Zeno of Citium, the originator of Stoicism, and Epicurus of Samos, father of Epicureanism, had made reputations for themselves as lecturers at Athens, attracting many disciples. Their two philosophic foundations, respectively designated the Stoa and the Garden, came to dominate ancient intellectual life from that time forward until well into the imperial Roman era.

While both Stoicism and Epicureanism were comprehensive systems that provided ordered explanations of the workings of the universe, the foundations of human knowledge, and the place of divinity in the cosmos, each specialized in strategies for attaining happiness through rational victory over the passions and willing conformity with nature’s laws. Sexual desire, a natural human appetite but also, when misdirected, a source of great psychic distraction, posed an obvious problem in any such ethical system. Depending upon circumstances, erôs was a force for both good and ill: it could heighten the lover’s perception of self and others, impel him to generous acts of kindness, further the socialization of the young, and strengthen the bonds of community life, but it could also lead to madness, violence, and disregard for the well-being of the beloved (Nussbaum 2002: 60–65; Sihvola 2002: 201–2). Lovers who were themselves decent and altruistic might be hurt by the bad faith of their partner. Aristotle declares that the built-in asymmetry of the pederastic relationship generates unfortunate misunderstandings that subvert its goal of lifelong philia (Eth. Nic. 1164a.2–8):

In erotic affairs the erastês sometimes charges that his excessive affection is not reciprocated – perhaps there is nothing lovable about him – and meanwhile the erômenos often complains that the other had formerly promised everything and now does not live up to his promises. Such things happen when the erastês befriends the erômenos seeking pleasure and the latter befriends the erastês for personal advantage, and neither one can supply what is expected.15

Elsewhere in the Nichomachean Ethics (1158a.10–13, 1171a.10–13), he defines erôs as “an excess [hyperbolê] of philia” directed to one person exclusively. Given Aristotle’s preference for the mean, a notion of desire as excess does not augur well.

The cultural dilemma created by conceptualizing love as such an explosive blend of pleasure and danger, benefits and risk, gave rise to a multiplicity of possible solutions. Fifth-century oligarchic discourse on pederasty waxed enthusiastic about admiration of beauty and manly promise while mentioning copulation only in guarded terms. Plato contended in the Phaedrus that chaste passion for another could be a path to spiritual illumination for the couple, while in the Symposium the lover’s moral ascent is effected through transference of desire to intangible abstract goods. All these approaches identify the affective component of erôs as advantageous, the carnal component as bad, or at least potentially injurious. Many Hellenistic thinkers approve a converse strategy: natural bodily impulse is not wrong, but the feelings attached to it can be destructive. Sex without erôs, or with a watered-down form of erôs, may be enjoyed; fixated passion is to be avoided at all costs.

We can begin with the Cynics Diogenes and Crates, whose positions may seem rather attractive after exposure to the Athenian Stranger’s inflexibility. For a Cynic, nature is the only guide to virtue; society, populated by fools, is ridden with senseless prohibitions. While Diogenes practiced masturbation to show that the individual can satisfy his own desires without the help of others, he also advocated that women and children ought to be held in common, and that sexual union should be by mutual consent (Diog. Laert. 6.72). For him, boys and women were as morally capable as men of forming liaisons on the basis of rational choice. His doctrine of self-sufficiency did not mean living in isolation; rather, it enabled the wise man to contract free and independent associations with individuals of both sexes (Rist 1969: 71).

Diogenes refused to recognize marriage, along with other civic institutions, but his pupil Crates entered into an egalitarian marriage with Hipparchia, the sister of one of his students. Crates was ugly, says Diogenes Laertius, and when he exercised unclothed was laughed at (6.92). When he visited Hipparchia’s brother, however, she fell in love with his precepts and way of life and threatened to kill herself if she could not marry him (6.96–8). Her parents, at a loss, asked Crates to discourage her. He removed all his clothing and, standing naked before her with cloak, staff, and knapsack lying beside him, said, “Here is your groom and his goods; think about it.” Hipparchia agreed to be his partner, and from that time forward lived as he did, dressing in the same fashion, begging for subsistence, and preaching in the marketplace. She even accompanied Crates to dinner and put up with coarse mockery from men who did not take her vocation seriously. We are told that the couple attempted to consummate their union in public (Apul. Fl. 14), a scandalous allegation, probably untrue, but theoretically proper Cynic procedure. However much of this is romantic invention after the fact, in their own lives Crates and Hipparchia confirmed the premise that a heterosexual relationship established by full mutual consent could be stable and enduring.

Zeno of Citium was a student of Crates. Stoic morality was shaped by the Cynic vision of living according to nature, which for Zeno was both the goal of life and the measure of virtue (Diog. Laert. 7.87). Reason (logos), the defining faculty of the human being, was an extension of the divine reason permeating the material order. Fate laid down the broad pattern of a human life – circumstances of birth, health, progeny, attainments and reversals, date of death – in keeping with a preordained design for the universe. Virtue consisted in voluntarily submitting to the divine plan, choosing things in accordance with nature and rejecting those that were not. Sexual pleasure was attached to behavior that conformed to the natural inclination of the human being. In early Stoic thought, furthermore, sexuality was not purely a bodily experience, for the genital function, like those of the eyes, ears, and other sense organs, was among the parts of the human soul presided over by reason (Gal. PHP 3.1.9–15, SVF 885). Contrary to Greek popular belief, then, sex was inherently rational and not morally questionable, provided that indulgence was regulated by the higher governing agency in the soul (Gaca 2003: 68–73).

Zeno’s Republic, his own account of the well-structured state, has come down to us only in fragments, but we have many references to its provisions. Opponents of the Stoics singled it out for attack and later members of the school found it embarrassing, partly because of its teaching on gender and sexuality. Zeno envisioned a community of the wise brought into accord by Eros, god of friendship and freedom: “Eros,” he is reported as saying, “is the divinity who promotes the security of the city” (ap. Ath. 13.561c). That seems unexceptionable, except that the wise were expected to consort with the young, seeking out those whose appearance indicated a natural disposition to virtue (Diog. Laert. 7.129), and, through erôs, forming friendships, which might well include consensual sexual activity, to cultivate that potential for goodness. The lover was to maintain relations with a beloved until the latter reached the age of twenty-eight, an educational provision laid down because full moral development takes longer to achieve than physical maturity (Schofield 1991: 33–4).

Although his directives are couched in pederastic terms, Zeno’s ideal state included female as well as male sages and doubtless allowed for homoerotic pair-bonding between women and girls as well as men and boys. As for heterosexual relationships, he endorsed the Cynic proposal, which drew upon Plato’s Republic, for a community of wives – supposedly this would forestall jealousy arising from adultery – together with the claim that mutual consent, and only mutual consent, was necessary for a valid union. He also advocated unisex dress and exercise in the nude for both sexes (Diog. Laert. 7.33). Indeed, if human beings were to be sexually communal, even incest was permissible (SVF 3.753; cf. Gaca 2003: 81). But the Stoics denied that the erôs that imbued these civic relations was a passion, for they regarded passions as excessive, disobedient to reason, and contrary to nature (SVF 3.378). Passions were the result of mistaken judgments, and someone in the grip of obsessive erôs, such as Medea, would find herself in that predicament because she had formed false conclusions about what was required for her happiness. Hence there was one erôs for the wise and another for fools (Inwood 1997: 61–8). Later generations of Stoics repudiated Zeno’s thinking on sex, gradually arriving, under the influence of upper-class Roman morality, at a position close to that of Plato’s Athenian Stranger – permissible only in marriage, employed for procreation. Under its founder and his immediate successors, however, Stoicism came to terms with desire by subjecting it to the tempering effects of rationality.

Epicureanism, the other great Hellenistic belief system, denied the possibility of an afterlife and held that in this one pleasure is the supreme good: seeking pleasure and avoiding pain are natural human tendencies and essential for happiness. Yet Epicurus’ definition of “pleasure” does not license unrestrained hedonism. Pleasures are divided into two sorts: the first a combined sense of mental ease (ataraxia) and general physical satisfaction; the second a more intense momentary gratification, physical or mental. The former is attained by the removal of pain. “The flesh,” he says, “cries out not to be hungry, not to be thirsty, not to be cold. Whoever has these and expects to continue having them could match even Zeus in happiness” (Sent. Vat. 33).16 If you are content with your situation once pain is taken away, desiring nothing further, that is enough for the good life. As for the temporary or “kinetic” pleasures – sipping a cold beer on a hot day, solving a tough math problem – they do not increase one’s contentment if it exists already but just impart a passing buzz. The latter pleasures, furthermore, often bring pains in their wake (the hangover incumbent on the fifth cold beer), and the wise man should make a rational calculation about which pleasures can be indulged safely without accompanying pain. Desire for those bringing too much pain must be resisted. Sometimes, though, brief pain is wisely endured for the sake of the greater good (for example, the “A” on the test was worth the hours spent solving the math set). Thus Epicurus can assert in his Letter to his friend Menoeceus that “sound judgment [phronêsis] is more valuable than philosophy” (132).

While food, drink, and sleep are naturally pleasurable and also necessary for survival, sex, though equally natural, is not absolutely necessary. Sexual desire is aroused by a combination of visual stimulus and the physical accumulation of semen in the genitals (Plut. Amat. 766e). Being unnecessary, it is easily dispelled if not indulged (RS 26); the consequences of indulgence, on the other hand, can be severely painful. A probable excerpt from another of Epicurus’ letters warns (Sent. Vat. 51):

I hear from you that the movement of your flesh is too much inclined toward sexual intercourse. As long as you don’t break the laws or disrupt well-established customs or cause grief to any of the neighbors or wear out your health or squander your basic goods, indulge your proclivity as you see fit. But it’s actually impossible not to be constrained by one of these factors. For sex never does you any good, and you’re lucky if it doesn’t harm you.

This blunt declaration notwithstanding, there are indications that sex under proper circumstances could be part of the well-ordered Epicurean lifestyle. Gossip about scandalous goings-on among the master and those disciples who lived with him at his estate, the Garden (and who included women, as we will see), can be discounted: Epicureans were tempting targets of smear campaigns. On the other hand, Epicurus does name the pleasure of sexual intercourse, along with those of taste, smell, sound, and vision, among those that come first to mind as goods, adding that mental delight consists in the hope of enjoying them without pain (Cic. Tusc. 3.41). Sexual desire apparently can be gratified if its discomforts will be no worse than, say, those occasioned by walking a mile to a friend’s house for dinner.

Nussbaum observes that the Garden, with its focus on individual happiness, offered “no strong positive motive for sexual activity,” since marriage and child-rearing were very likely discouraged except under unusual circumstances (1994: 152–3). Yet Epicurus also made friendship, philia, central to the attainment of the good life and insisted that the wise man will endure pains and hardship, and may even sacrifice his life, for a friend’s sake (RS 27; Diog. Laert. 10.120). It is conceivable, then, that a relationship of philia between man and youth, or man and woman, might include a sexual component, provided that both parties benefited from it and that such intimacy enhanced, rather than endangered, the good will and affection each felt for the other. What was indubitably bad, on the other hand, was erôs, which Epicurus defined as “an intense longing for sex accompanied by smarting and distress” (Us. 483). In a move analogous to that of Stoicism, he blamed the sorrows of passionate love on a false belief in the importance of the love object that had attached itself to the sexual impulse (Brown 1987: 112–15). The fundamental difference between the two systems is that the Stoics did originally leave room in the sage’s life for a safe brand of vanilla sex. Epicurus suspected that sex, by its very nature, could hardly ever be safe.