7

Early Rome: A Tale of Three Cultures

Academics’ ingrained habit of compartmentalizing the history of classical antiquity as separate “Greek” and “Roman” segments can mislead students into thinking that the two peoples knew nothing of each other until Rome, having defeated Carthage in the Second Punic War (218–201 BCE), started looking around for somebody else to conquer. Yet archaeological evidence indicates that almost four centuries earlier the Romans were already well acquainted with Greek mythology and art. For example, the shrine of the Niger Lapis, or Black Stone, in the Forum was sacred to Vulcan (Hephaestus), and a votive deposit placed there in 580–570 BCE contained a fragment of an Attic black-figure cup illustrating the myth of Hephaestus’ return to Olympus. A late sixth-century monumental grouping from the roof of an archaic temple in the Area Sacra di Sant’Omobono, now on display in the Montemartini Museum in Rome, portrays the apotheosis of Hercules, the Greek hero Heracles, who is being escorted to Olympus by Minerva (Athena). Both figures are immediately recognizable by their distinctive attributes of lion-skin and helmet, as seen on Attic vase paintings of the same period (Cornell 1995: 147–8, 162–3). Religion, art and artifacts, and other elements of Greek culture were introduced into archaic Rome either through Etruscan intermediaries or directly, via commerce with the Euboean colonists of Pithecusae (modern Ischia) and Cumae and the settlements of southern Italy (Magna Graecia). To commence an account of Roman Hellenization with the first diplomatic contacts between Rome and the Greek East in the third century BCE is therefore to begin too late: from its origins Rome had always known Greek influence in one form or another.

Isolating what is distinctly Roman in Greco-Roman constructions of sexuality cannot be done, then, by going back historically to a pristine pre-Greek era. Accounts of very old cults, like the Lupercalia, describe odd practices but offer no indication that underlying beliefs about human fertility differed from contemporaneous beliefs in mainland Greece.1 At an early date, Roman gods were so closely identified with their more robust Greek counterparts that we are unable to turn to mythology to extract indigenous notions of Cupid or Venus. Literature, which is our best witness to patterns of thinking, was Hellenized from the outset: our earliest surviving texts, Plautus’ comedies, written and produced between 205 and 184 BCE, are adaptations of Attic New Comedy. Lastly, the “Roman art” familiar from Pompeian wall paintings and statuary is for the most part a late Hellenistic art: fashioned by Greek craftsmen, it pleased the eye of Roman purchasers but, with certain exceptions, did not radically depart from the themes and styles of earlier Greek art. Many of the pieces found at Pompeii and Herculaneum are, in fact, reproductions of Greek works created in the fifth or fourth centuries BCE.

The impact of Etruscan culture is another complicating factor. Although the origin of the Etruscans was a disputed matter in both antiquity and earlier modern times, archaeologists now concur that their civilization developed out of the indigenous Villanovan culture of the thirteenth to eighth centuries BCE. By the sixth century, several confederations of major Etruscan cities had been established, extending from Northern Italy down to the Bay of Naples (Barker and Rasmussen 1998: 43–4, 141–78). The Tarquin dynasty, which ruled Rome until its expulsion in 510 BCE, had Etruscan ties. According to legend, its patriarch Tarquinius Priscus had been born in Etruscan Tarquinii, the son of a Corinthian immigrant; his mother was a native of that city and he himself had married Tanaquil, an Etruscan woman of high rank (Liv. 1.34.1–5). From the late seventh through the sixth centuries, when the Tarquins were once thought to be in power, the Roman populace had supposedly adopted a wide array of Etruscan institutions, including architecture, religious practices, ceremonials such as the triumph awarded a victorious general, military tactics, social organization, dress and magisterial insignia, the alphabet, and the calendar (Ogilvie 1976: 30–61). Recent scholarship, however, questions both the fact of Etruscan domination and the extent of Roman borrowing, positing instead a cultural amalgamation of “Greek, orientalising and native Italic elements” shared by all communities in this area of central Italy (Cornell 1995: 171–2). Whatever the case, it seems worthwhile to look briefly at Etruscan art for evidence of attitudes toward gender and sexuality that differ from those we have observed among classical and Hellenistic Greeks. Surviving Etruscan texts are of no help here, for most are funerary inscriptions and the rest religious.

We noted previously that the public visibility of aristocratic Etruscan wives scandalized Greek observers. Engraved metal goods fashioned for such women – mirrors and bronze chests – served as conspicuous markers of their status and provide inscriptional evidence for their literacy; the elaborate designs frequently show women and men interacting in mythic and real-life situations. Bonfante (1986: 240) notes the remarkable emphasis on groups of older women and younger men, sometimes lovers, sometimes identified as mother and son. The wealth and luxurious tastes of upper-class Etruscan women are reflected in detailed depictions of their fashionable dresses, shoes, hats, and jewelry on metalwork and in tomb paintings. All these representations emphasize leisure and enjoyment. They clash not only with classical Greek idealizations of the circumspect mistress of the household but also with Roman ideology valorizing the industrious matron.

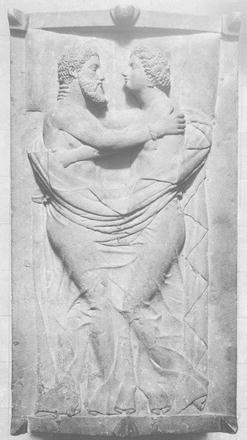

As for sex, its symbolic presence in Etruscan funerary art is particularly striking. The front panel of a cinerary urn from Chiusi, now in the Louvre, depicts satyrs engaging in wild copulation at a banquet (Brendel 1970: 28 and fig. 21). Some tombs, such as the sixth-century Tomb of the Bulls in Tarquinia, contain paintings of intercourse, both same-sex and heterosexual; motifs in other tombs include a phallus, a man farting or excreting, and a scene of a woman being whipped. These have been interpreted as apotropaic images protecting the dead from harm and, in the case of the last picture, a Dionysiac allusion to suffering and rebirth. Other tomb paintings show married couples warmly conversing at dinner. Sarcophagi display husband and wife reclining in an embrace, as in the famous “Sarcophagus of the Spouses” from Cerveteri, now in the Louvre, or nude and lying together under a single blanket, “making eye and body contact” (Hallett 1988: 1267) in the sensuous manner shown here (fig. 7.1).

Bonfante argues that this use of erotic imagery in familial burial contexts is life-affirming, since it insists upon the continuity of affection beyond the grave and may also work to ensure the fertility of surviving descendants (1996: 155, 166). Roman funerary art, in contrast, does not make use of overt sexual symbolism. We will see, though, that the employment of the phallus as an apotropaic charm was ubiquitous in Roman daily life, and it is arguable that other household decorations from Pompeii and Herculaneum with seemingly prurient sexual content (only recently put on display in the National Archaeological Museum at Naples) may have been intended to bring the beholder good luck rather than arouse him.

The Pecking Order

Bearing in mind that some aspects of a Roman model of eroticism may be of Etruscan origin, can we isolate any conspicuous departures from the patterns we have identified in Greek materials? In Latin literature produced between approximately 200 BCE and 14 CE, that is, during the last two centuries of the Republic and extending into the principate of Augustus, the first Roman emperor, the conceptual framework of sexual relations seems much the same as the one prevailing in Greek art and literature from the archaic to the Hellenistic period: sex is, in essence, a dominance–submission relationship. Although the “penetration model” does not cover the full spectrum of sexual acts performed in those Roman texts, a hierarchy of dominance and submission is assumed even in circumstances where participants deviate from the norm.

However, factors determining sexual dominance were not assigned the same degree of weight in the Greek polis and the Roman megalopolis because social configurations were not the same. In the classical Greek city-state, where the male citizen population was relatively small and homogeneous, the crucial requirement for dominance over boys, women, and non-citizens was adult manhood.2 Roman social stratification was far more complex. In one specialist’s words (Fredrick 2002: 9–10):

Rome in the first century BCE presents a finely nuanced social hierarchy from elite senators and knights down to the freeborn; “beneath” them, freed slaves of low political status but considerable economic opportunity (many enjoyed economic superiority over freeborn citizens); “beneath” them, cadres of domestic and rural slaves carefully graded in status and function (many slaves enjoyed better living conditions and more responsibilities than free citizens).

Owing to these paradoxes of stratigraphy, rank and class were more decisive in calibrating sexual power relations than physiological manhood. During the Republic, the body of the Roman vir, the adult citizen male, was regarded as inviolable, legally protected from sexual penetration, beating, and torture. Thus biological sex would appear to confer bodily immunity. In actuality, though, the word vir was applied selectively to adult freeborn citizen males in good standing and positioned at the top of the hierarchy; slaves, freed persons, and “disreputable” individuals did not enjoy the same protections from assault as the well-born did. What seems a distinct physiological term is actually a description of “gender-as-social-status,” involving factors such as birth, citizenship, and respectability that to our way of thinking have nothing to do with gender (Walters 1997: 32). For the Romans, they did, because the male who did not enjoy such bodily protection was automatically effeminized.

The institution of patronage, which created vertical networks of authority and influence, complicated existing social asymmetries. Patronage is a system in which two individuals of unequal status, the higher-ranking patron and his lesser client, trade goods and services on a personal basis, each according to his means (Saller 1982: 1). The democratic ideology of classical Athens was hostile to personal patronage, since it undercut notional political equality by calling attention to disparities in wealth and social standing (Millett 1989: 17). In Rome, however, patronage relations permeated all levels of society. Former masters and mistresses automatically became patrons of their freed slaves, who were expected to provide part-time assistance to them and show ongoing respect. Because the system was based on social advantage rather than sex, high-ranking women could have male clients of good, though inferior, birth.3 Attention to intricate gradations of social position spilled over into sexual relations and became a controlling factor in the construction of Roman sexuality. The slave’s body was wholly at his master’s disposal; ex-masters might even continue to obtain sexual services from freed slaves, though whether they could demand them is debatable (Sen. Controv. 4 pr. 10; Butrica 2005: 210–21). Consequently, a freeborn client’s public deference to his great patron might be scandalously distorted through rumor and innuendo into a quasi-sexual mode of servitude (Oliensis 1997: 154–5). Roman social and sexual hierarchies are two interrelated systems that “can hardly be understood independently” of each other (Richlin 1993: 532).

Social standing is so closely tied in the Roman imagination to exercise of sexual privilege that writers regularly employ phallic imagery as a concrete metaphor for the workings of power. The poet Catullus, having served on the staff of Memmius, governor of Bithynia in 57–56 BCE, vents his annoyance at his former boss: “O Memmius, while I lay on my back you slowly rammed me in the mouth with that whole beam of yours well and at length” (28.9–10). In actuality, Memmius had done nothing more than impose restraints on his subordinates to prevent them from financially exploiting the natives, thereby disappointing Catullus, who had gone to Bithynia hoping to make money. Greek authors restricted such use of obscenity as a symbolic code to genres such as iambic verse and Old Comedy, but in Latin materials it appears more frequently, and differences in genre only govern whether the activity is vividly represented, as in Catullus’ complaint, or implied through euphemism. This troping strategy accounts for many of the racy tidbits about the private lives of Roman women and emperors that found their way into ancient history and biography and are still regarded by some as credible fact.

Apart from the Roman tendency to sensationalize political and social transactions between unequals by painting them in lurid hues, three other areas of cultural dissimilarity have been pinpointed. The first is a salient difference recently explored in considerable depth. Although sexual attraction to youths was regarded as completely normal, just as it was in Greece, Roman men were rigorously prohibited by law as well as custom from sexual contact with freeborn citizen boys. Violation of the physical integrity of a citizen youth was treated as the equivalent of unlawful relations with unmarried women and punished as stuprum, a criminal sexual act (Fantham 1991; Williams 2010: 103–36). In Plautus’ Curculio, the hero, infatuated with a courtesan owned by a pimp, receives the following advice from his slave (35–8):

Nobody forbids anyone to walk on the public street;

as long as you don’t cut a path through a fenced area,

as long as you keep away from the bride, the widow, the virgin,

the young man, and freeborn boys, love whom you please.

Pederasty, as an institutionalized cross-generational relationship of two Roman citizens, thus becomes unthinkable. Furthermore, because slaves and prostitutes were the only legitimate objects of male homoerotic desire, relationships with boys were often treated as trivial even by those who viewed them in a favorable light.

A second difference in attitudes has to do with concerns surrounding the chastity of the matrona, the married woman of respectable status. Elite matrons were publicly visible representatives of their natal, even more than their marital, families (Hallett 1984); their legal and economic position assured them a central role in religious observance and a key part in the workings of the patronage networks that permeated the social structure. That visibility, however, made women’s sexual behavior a sphere of unease for the community as well as for their kinfolk. The prosperity and power of the state, the res publica, depended upon the continued good will of the gods, who were profoundly offended, it was thought, by the wickedness of the ruling classes. If sexual immorality was rampant (and in Roman moralizing speech it always is), the fault was not laid at the door of the adulterer, as in Greece, but at that of the irresponsible, pleasure-seeking woman (Liebeschuetz 1979: 45–7). Adultery was therefore a serious ethical issue in both Greece and Rome, but with different causes and consequences in each society.

Finally, a more tenuous contrast has been perceived: Roman society is variously described as “sadistic” (Kiefer 2000 [1934]: 75–117), “macho” (Davidson 2001: 28–9), or “Priapic” (Richlin 1992; Williams 2010: 18) to a degree that Greek society was not. According to this hypothesis, a “hyper-masculine identity,” to borrow Craig Williams’s phrase, was publicly demonstrated by aggression – verbal, as in attacks upon political or legal opponents, or even physical, if the other party was of low status. Hostilities took place before witnesses because power relations had to be acknowledged openly. Sex, violence, and spectacle are thus securely linked together in the Roman mentality. The popularity of gladiatorial games, with their accompanying slaughter of wild beasts and brutal punishments of condemned criminals, might be explained in this fashion (Lilja 1983: 135). Whether there was, in fact, a greater propensity toward violence in Roman culture and, if so, what factors might account for it are questions that deserve much fuller investigation. In the remainder of the chapter, we will consider each of the three areas of diversity listed above in greater depth, turning to literature, art, history, and law to bring such elements of Roman sexual ideology into better focus.

Imported Vices

According to the late first-century BCE historian Sallust, Rome fell from grace once she became mistress of the world (Sall. Cat. 10–13). Formerly her people had been virtuous, frugal, and self-disciplined, but the temptations of leisure and riches proved too much. Avarice and ambition began to erode morality. Under the dictatorship of Sulla, who seized control of Rome in 82 BCE, greed instigated property confiscations and massacres of Roman citizens. Roman armies had meanwhile been exposed to the softening effects of Eastern luxury. Disposable wealth invited degeneracy (13.3):

But the appetite for sexual offenses, gluttony, and other refinements had advanced to an equal degree: men played the woman’s role [viri muliebria pati, literally “men endured things done to women”], women made their chastity available; for dining they sought out all the products of land and sea; they slept before they felt a desire for sleep; they did not wait upon hunger or thirst, or cold, or fatigue, but by soft living anticipated all these things.

Here moral depravity manifests itself through a perversion of natural appetites, including those for food, drink, and sleep as well as sex.

That narrative of decline is one to which most concerned Romans would have subscribed, although they might have located the point of collapse earlier. In the middle decades of the second century BCE, traditionalists like Cato the Censor were already castigating fellow members of the nobility for their uncontrolled self-indulgence. Polybius, a Greek eyewitness of events in the capital city, reports that young men who had been exposed to Hellenistic opulence during the recent campaign (171–167 BCE) against King Perseus of Macedon were setting such a fashion for extravagance that outrageous sums were being paid for slave catamites and jars of imported smoked fish. Infuriated, Cato protested in a speech before the Roman people that “they could most readily recognize that the state was going to the bad, when pretty boys being sold fetched more than fields and jars of smoked fish more than ox-drivers” (Polyb. 31.25.5). In this and other moralizing texts, the same progression of events can be traced: money permits its possessors to wallow in pleasure, addiction to pleasure leads to even more heinous conduct, and the destabilization of the Roman state follows. Self-evident as this complex of ideas seemed to Roman writers, its assumptions require unpacking. For now we will let them stand, but you might want to pencil in a question mark beside Sallust’s and Cato’s statements.

In constructing such accounts, the Romans laid the blame for their deterioration on exposure to Greek ways. They represented native ancestral customs, or the mos maiorum, as strict and austere; debauchery was a foreign import. This contention encouraged scholars of a quarter-century ago to envision archaic Rome as a puritanical society where “acceptable sexual behavior was limited to heterosexual marital intercourse” (Hallett 1988: 1268) because the manpower demands of agriculture and warfare required procreation (Lilja 1983: 134). All forms of same-sex congress were supposedly disapproved, and homoeroticism only became a cultural practice after the upper classes began to adopt a Hellenized mode of life in the third century BCE. Ramsay MacMullen cites the number of Greek loan-words in what he calls the Roman “vocabulary of homosexuality”4 (paedico, the verb for anal penetration, derived from Greek pais, “boy”; pathicus and cinaedus, two Latin equivalents for kinaidos; catamitus, a young male sex object) and suggests that these, like similar Graecisms for items of luxury such as cosmetics, garments, and edibles, point to “a way of life imported as a package, and on occasion repudiated as such” (1982: 486). Citing the pronouncements of the Stoic philosophers Seneca the Younger and Epictetus, one can then argue, with MacMullen, that this aberrant way of life, which was confined to a minority, continued to be bitterly denounced by the rest of society; or one can declare, on the basis of the picture given by poets of the Augustan Age, that upper-class Romans had become so thoroughly Hellenized by the end of the first century BCE that relations with boys were “both very common and very lightly viewed” (Griffin 1986: 25). Either way, that is an impressionistic method of doing history, for the answer to the question of whether elite Roman males were converted to pederasty through contact with Greece will depend on the type of evidence one selects.

Later studies have clarified this issue by drawing the line between traditionally permitted and forbidden sexual objects. In Rome no blame was attached to the man who indulged in sex with either his own male slave or a male prostitute, provided that he took the active role and that financial expenditure, if any, was kept within reasonable limits (Cantarella 1992: 101–4; Williams 2010: 20–9). The poet Horace, who adopts an admonitory stance in his Satires, asks his addressee whether, when dying of thirst, he would demand a golden goblet to drink from, or disdain everything except peacock and turbot when starving. No? Well, then,

… when your groin bulges,

if a servant-girl or estate-born boy is handy, whom you can jump on

right away, would you prefer being ruptured by the swelling?

Not me; I want my sex ready and accessible. (Sat. 1.2.114–19)

To make his point, Horace strips away the romance of desire, picturing coitus as a process for relieving a bothersome physical urge and using one’s own property as the simplest and easiest way of doing it. The absolute indifference to the sex of the object in this quasi-ethical pronouncement should indicate that the act of copulation with a male slave was not, for the slave-owning population, a moral issue. As for the elder Cato, when he inveighs against the purchase of boys for sexual use, is he denouncing pederasty? Not in itself, any more than he is denouncing smoked fish. Rather, his anger is directed at rich young men who lavish enormous amounts of cash on personal gratification rather than earmarking wealth for productive agricultural projects. That waste of resources, in his view, is what threatens Roman stability (Edwards 1993: 177). Such feelings would be entirely characteristic of Cato; his frugality was legendary, and his sole criterion for judging something good was its use–value.5

Citizen youths were strictly off limits, though, and in fact the chastity of the freeborn boy was an area of considerable social concern. Below the age of puberty, such boys wore special clothing, a purple-bordered toga and a golden amulet (bulla) to mark their status. Matrons and boys were protected by law from unwanted attention; following them on the street, suborning their attendants, or pestering them was legally actionable (Ulp. Dig. 47.10.15.15–23). Another law, the Lex Scatinia or Scantinia, may have punished actual sexual congress with protected minors, but the provisions of that law are so unclear and so debated (see Cantarella 1992: 106–14; Richlin 1993: 569–71; Williams 2010: 130–6) that it is best left to one side. What is absolutely beyond doubt is that Roman jurists put unmarried women and boys on the same footing, defining intercourse with them as a sexual offense, stuprum, and, by the third century CE, prescribing capital punishment for an accomplished seduction (Paulus Dig. 47.11.1.2). Consequently, there was no provision for courtship of free citizen youths in the Roman scheme of sexual morality. Anecdotal evidence indicates that seductions of boys occurred, but concerns about adultery with matrons were far more prevalent.

Can we speak of “pederasty” at all when dealing with Roman practices of boy-love? Since the power dynamics in the relationship were so distinct from those courtships figured on Greek vases and imagined in the dialogues of Plato, it is hard to relate one to the other. Slave boys who were special favorites were known as delicati, “pets” – yet, no matter how indulged, were at the mercy of their owner. As for the prostitute, his client bought what services he wanted. Some pantomime actors were much in demand, like Bathyllus, reputed to be the favorite of Augustus’ friend Maecenas (Tac. Ann. 1.54), but even so were stigmatized and suffered legal disabilities because of their profession (Edwards 1997). In such relations there was no room for the flexibility and negotiation theoretically possible in the encounter of the Greek erastês and erômenos, with its moral demands on both citizen participants.

In literary renderings of homoerotic affairs, Roman poets adopted the romantic conventions of Hellenistic epigram, praising the boy’s beauty and lamenting his coyness, avarice, infidelity, and so on. Catullus teases us by addressing pederastic verse to a Juventius, the offspring, it is hinted, of a genuine old Roman family (poems 24 and 81; on the family itself, of Etruscan origins and consular rank, see Cic. Planc. 19 and 58). Yet the name, derived from iuvenis (“youth”), is implausibly apt; though its owner is real, we can guess at a private in-joke in which a friend is humorously written into a stock situation (Macleod 1973). Horace and Tibullus give the beloved a Greek name to signal that they write in the tradition of Alcaeus and Anacreon. Latin authors, then, handle these pederastic motifs in an artificial way. Perhaps one attraction of such poetry was its evocation of a fantasy situation that could glamorize the mechanics of sexual transactions with slaves and hired partners.

Bringing Women under Control

Greeks and Romans were fascinated analysts of divergences in each other’s customs. Matters of sex and gender drew the attention of observers on both sides. Polybius, the product of a culture in which respectable women, even after the social transformations of the fourth and third centuries, were still expected to be relatively unobtrusive, was struck by the ostentation of the female relatives of his Roman friend Scipio Aemilianus. Here is his recollection of how Scipio’s aunt Aemilia paraded her wealth when attending women’s cult ceremonies (31.26.3–5):

It happened that Aemilia, for this was the name of the aforementioned woman, had a magnificent cortege in women’s processions, because she had shared the life and fortune of Scipio [Africanus, the adoptive grandfather of Scipio Aemilianus] at its height. For, apart from the ornamentation of her person and her mule-cart, all the baskets and the cups and the other paraphernalia of sacrifice were of silver or gold, and all the objects accompanied her on these conspicuous outings, and there were a corresponding number of slave-boys and maidservants following along.

When Aemilia died, Polybius goes on, Aemilianus, who inherited her estate, bestowed these trappings on his own mother Papiria. Though of high birth, she had been divorced and was living on modest means. Up until then, Papiria had not participated in public pageants, but at the next festival, sure enough, she turned up with the retinue that had been Aemilia’s. Female spectators recognized the muleteers, team, and wagon, and, impressed by her son’s generosity, called down blessings upon him (6–8).

It was customary for aristocratic Roman ladies to advertise the achievements of male kin through their luxurious clothing and appointments; these were, as a speaker in Livy’s history affirms, the equivalent of men’s magistracies and badges of office (Liv. 34.7.8–9). The fact that the populace was familiar with Aemilia’s vehicle indicates that such displays made quite an impression on bystanders. However, the man who funded them might view them in a different light: “I don’t much like these highly connected women, their airs, their huge dowries, their loud demands, their arrogance, their ivory carriages, their dresses, their purple, who reduce their husbands to slavery with their expenses” (Plaut. Aul. 167–9). Cato, needless to say, was of the same mind. Attempting to defeat the repeal of a sumptuary law restraining women’s extravagance, he is made to argue: “Whoever can pay from her own means, will; she who can’t will ask her husband. That poor man – both the one who consents and the one who doesn’t, since what he hasn’t given he’ll see given by someone else” (Liv. 34.4.16–17). Adultery is always one step behind luxury in this way of thinking.

Cornelius Nepos, who wrote Latin biographies of eminent men, observes in his preface that different peoples judge different things honorable and shameful, evaluating them according to ancestral tradition. To illustrate: the Athenian Cimon married his half-sister on his father’s side, a criminal act by Roman standards; in Crete it is praiseworthy for adolescents to have many lovers; Spartan widows take paramours; and Greeks see no disgrace in being an athlete or actor. “Many things, on the other hand, which we deem proper they would pronounce appalling – specifically, the conduct of our women” (Nep. 6–7):

For what Roman man is ashamed to escort his wife to a dinner party? Or what lady of the manor does not sit in the forecourt of the house and venture out in public? In Greece it’s very different, for a woman is not summoned to dinner unless it’s with relatives, nor does she reside anywhere but in the interior part of the house, which is called the “women’s quarters,” where no one goes except those connected by close ties of blood.

Despite Nepos’ bland assurances that Roman husbands were comfortable with their wives’ presence in society, however, the activities of women outside the home, especially among the upper classes, were perceived as a weak point in the ethical system and a potential danger to the collective order.

The story of the rape of the Sabine women, one of Rome’s founding myths, provides archetypal justification for the elite Roman wife’s participation in men’s affairs. Romulus and his band of fugitives and outcasts, seeking wives, invite the neighboring Sabines and their families to attend a festival, then, at a given signal, kidnap the young women present. When the Sabines, having assembled a coalition, march on Rome to rescue their daughters, the women run between the two armies, holding up their babies (it took a while to assemble that coalition), and negotiate a peace between Sabine fathers and Roman sons-in-law. Given in marriage, the daughter of a leading senatorial family was expected to follow the Sabine women’s example of maintaining a dual loyalty (Pomeroy 1975: 186). Marriage was a practical medium for cementing political and economic alliances between two such families. Wives, who remained closely bonded to their fathers (Hallett 1984: 76–110), could serve as intermediaries when strategies were being formulated, and, if differences arose between members of the natal and marital families, were expected to help resolve them. Their political interests were notionally, therefore, an extension of a praiseworthy readiness to assist the men related to them by blood and marriage.

There were, however, two distinct forms of marriage. Roman fathers maintained permanent control, patria potestas, over their adult sons and daughters, which in theory extended to possessing rights of life and death over them (Just. Inst. 1.9). Yet custody was transferable, and under one arrangement the bride became subject to the authority (manus) of her husband. Whatever property she owned was reassigned to him as dowry (Cic. Top. 23). Legally, she entered his family on the same basis as a daughter: if he died intestate, she shared in his estate equally with her children (Treggiari 1991: 28–9). In the other type of marriage, the bride and her property remained under the authority of her own father while he lived. If she died without making a valid will her natal family, parents or siblings, would automatically inherit. Should her father predecease her, she became independent, although permission of a male guardian, or tutor, often a member of her paternal family, was required for important legal and economic transactions. Tutelage allowed her kinfolk to keep an eye on her estate, for she would need her guardian’s approval to bequeath an inheritance to any outsiders, including her own children – who were part of her husband’s family, not hers (Treggiari 1991: 32). Because upper-class women had become very wealthy by the end of the Republic, owning considerable property and managing it on a day-to-day basis themselves, this latter marriage arrangement came to prevail, as it was in the best financial interests of blood kin. However, marriage without manus meant that a husband technically could not restrict his wife’s person or her business dealings, whereas her father or guardian, who could, lived in a different household and was not in a position to supervise her. This gave women considerable personal freedom and allowed them to operate on their own initiative, even in the public sphere (Pomeroy 1975: 154–5).

Although the activities of elite Roman women as patrons, investors, creditors, and benefactors are under-reported compared with those of their male counterparts, enough documentation exists to indicate that they were well integrated into wide commercial and economic networks. They were also energetically involved in conferring favors and lobbying. The Romans would not have understood our insistence upon intrinsic merit and lack of favoritism in appointments: for them, a candidate was especially well qualified for a job if someone close to power was able and willing to pull strings on his behalf. Wives and mothers of magistrates, provincial governors, and military officers were strategically placed to do so and their assistance was regularly sought. If pressure of this sort was applied to help male relatives, it was usually condoned, since female kin were expected to support the careers of family members. Thus Seneca, later to become Nero’s chief advisor, publicly thanks his mother Helvia for financial resources and benefits that furthered his advancement but notes quite pointedly that she had not called in that debt by taking advantage of his own station to ask favors for others, as many mothers would do (Helv. 14.2–3).6

The problem with women’s involvement in dealings of this kind, where gifts, loans, benefits, and legacies greased the wheels of patronage by creating reciprocal obligations to be repaid, was that by its very nature it was more ambiguous than men’s (Dixon 2001: 100–6). Pulling strings could be commendable, as when a son’s career was being launched, or sinister and corrupt, as when wives of governors were accused in the Roman senate of using their presence abroad to enrich themselves (Tac. Ann. 3.33–4). When influence was underhandedly applied, men feared the subversion of legitimate decision-making power. Even if a woman did not play for such high stakes, and was only interested in getting a good return on her capital, loans and investments involving men other than her kin could be misinterpreted as sexually motivated. The classic instance is the loan the noblewoman Clodia Metelli made to M. Caelius Rufus, at that time an associate of her brother P. Clodius Pulcher (Dixon 2001: 102). When Caelius was later prosecuted on a charge of street violence and Clodia appeared as a prosecution witness, Caelius’ lawyer Cicero maliciously twisted help for her brother’s confederate into proof of sexual intimacy (Cic. Cael. 31). Cicero himself once considered borrowing money from a certain Caerellia, elderly enough to be above suspicion, yet he was still warned that for a man of his stature being in debt to a woman made a bad impression (Cic. Att. 12.51.3).

Adultery was an extremely important matter in Roman society, as the number and variety of sources on the topic attest (Richlin 1981). Although the honor of fathers, brothers, and husbands was not as compromised by a woman’s misconduct as it was in Greece (Treggiari 1991: 311–12; Edwards 1993: 54–5), men must still have been troubled by the possibility of public scandal and consequent notoriety.7 Jokes in Martial (6.39) and Juvenal (6.76–81, 597–601; 9.86–90) on children not sired by their putative fathers indicate that husbands may have been nervous about spurious offspring.8 In addition to those issues, such unease seems an obvious way of displacing vague misgivings about wives’ independent conduct of their business and social affairs onto a tangible area of concern.9 Lastly, anxieties over societal changes in late Republican Rome precipitated by continued civil unrest, including a loss of confidence in patronage ties and the weakening of accepted class boundaries, appear to find concrete expression in tales of well-born adulteresses attracted to social inferiors (Edwards 1993: 52–3). Adultery therefore may be a metaphor for a number of broader worries that had nothing to do with female sexual conduct.

Male alarm about a woman’s associations with other men was not, of course, completely unfounded: opportunities for wrongdoing were available especially for someone like Clodia Metelli, a widow who lived in her own house on the Palatine Hill and was no longer subject to a father’s jurisdiction. Few seriously doubt that she did have an affair with the poet Catullus (see below). However, we cannot know how much of what Cicero said to discredit her was sheer invention (Skinner 1983; Dixon 2001: ch. 9; see now Skinner 2011: 96–116). That has not stopped scholars, even in these more mistrustful times, from swallowing his allegations wholesale and regurgitating them as historical “facts” about Roman noblewomen.

When Julius Caesar’s nephew and adopted son Octavian, later the emperor Augustus, defeated Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BCE, it marked the end of a century of civil war and internal discord. Roman thinkers had been quick to assign blame for the sufferings experienced by the peoples of Italy and the provinces during this period to the arrogance, covetousness, and ambition of powerful leaders – the Gracchi, Marius, Sulla, Pompey, Caesar, Marc Antony, and their friends and supporters. The struggles they engaged in were considered virulent symptoms, however, of a graver disease, the flagrant immorality of the elite. Justification of Rome’s rule over the rest of the world was based on her ability to impose a fair and stable peace on warring nations, which required that she herself had to demonstrate her own moral capacity to govern (Galinsky 1981: 134–8). Leading families’ neglect of religion, resistance to marriage and reproduction, and tolerance of adultery were thought to have provoked divine wrath, endangering Rome’s claims to empire. Already in 46 BCE Cicero had urged Julius Caesar, then dictator, to shore up a collapsing society through strict laws that, among other things, would repress license and further the propagation of children (Marcell. 23). In January of 27, after annexing Egypt, discharging his veterans, and celebrating a triple triumph, Octavian proclaimed the restitution of the Republic. In return, he obtained from the Senate a grant of proconsular imperium (“military command”) and accepted the title of Augustus (“venerable”) in recognition of his capacity for principled leadership (Galinsky 1996: 15–16). From that point on, he undertook the long-term task of sponsoring a program of civic and moral renewal that would restore religion and family to a central place in Roman aristocratic life.

In the year 28 BCE, as the princeps (“leading citizen,” another of his titles) informs us in an inscription, the Res Gestae, summing up his achievements, he began repairs on eighty-two urban temples (Aug. RG 20.4), a first step toward reconciliation with the divine order. Attempts, probably a year later, to impose legal penalties on unmarried men of the upper classes met with determined resistance (Suet. Div. Aug. 34). The love elegist Propertius may refer to that abortive project when he represents himself and his mistress Cynthia rejoicing at the withdrawal of legislation that would have compelled him to marry a woman of his own station. One couplet of his elegy expresses sour cynicism about the military needs driving efforts to boost the declining birthrate: “Why should I supply sons for patriotic triumph-processions? No child of my blood will be a soldier” (Prop. 2.7.13–14). That reaction would be only too predictable for a generation of young men born during the late 50s and early 40s who had lived all their lives under the cloud of civil war.

Perhaps in response to protests such as these, the concluding poem in Horace’s sequence of “Roman Odes,” published in 23 and addressing the ethical and political conflicts of the preceding decade, mounts a direct attack on the stereotype of the sexually daring woman popularized by Propertius and his fellow love elegists. Ode 3.6 begins by warning the present generation of punishments to come should the shrines neglected by predecessors continue to decay (lines 1–4). Roman rule is grounded on piety toward the gods, and recent military defeats hint at divine wrath not yet expiated (5–16). In the central stanzas, Horace traces the source of Rome’s evils to the home and the future bride who learns seductive wiles even before her marriage (21–32):

Generations pregnant with wrongdoing

first defiled marriage and offspring and the household;

flowing from this source a river of bloodshed

has saturated our country and its people; 20

the ripe virgin is pleased to learn Ionic dances

and is trained in coquetry and now already

thinks upon unchaste adventures

at a tender age;

soon she is seeking younger lovers 25

while her husband drinks, nor does she select

someone to give illicit delights to

furtively, while the lights are dim,

but openly sought, with her spouse’s knowledge

she rises, whether a shopkeeper bids her, 30

or the captain of a Spanish freighter,

a profligate buyer of shame.

Why should this young woman and her easygoing husband be held responsible for Rome’s military reversals? Because, Horace goes on, the men who defeated Carthage and the monarchs of the East were not born of such parents. Sons of soldiers, raised in the Sabine hills, while their fathers were away at war they toiled until sundown performing hard farm work – breaking ground with mattocks, hauling cut wood – at the bidding of a strict mother (33–44). Moral authority resides in the forceful woman who, in her husband’s absence, trains her sons in obedience and accustoms them to strenuous physical labor:

The salient role of the women portrayed admiringly in Latin literature was as disciplinarians, custodians of Roman culture and traditional morality. The familiar modern contrast between the authoritative father-figure and the gentle (and powerless) mother is strikingly absent. The ideal mother of Latin literature is a formidable figure. (Dixon 1988: xiv)

If Horace’s errant virgin is incapable of instilling such principles in her children, they in turn will be even more lax with their own children; the process is cumulative (Liebeschuetz 1979: 93). For this reason, and in spite of the hopes raised by endorsing Augustus’ scheme of temple renovation, the poem concludes on a note of despair: “the age of our parents, worse than our grandfathers, brought us forth, who are worse than they were and are soon to give birth to offspring even more degenerate” (46–8). Of all the late Republican-era sermons preached on the topic of moral decline (and there were quite a few), it is this poem that articulates most plainly the tight conceptual linkage between religious piety, military courage, and a stern maternal integrity far more rigorous than mere chastity.

Augustus succeeded in passing his legislation on marriage and children in 18 BCE (Cass. Dio 54.16.1–2). It comprised two statutes, the Lex Iulia de maritandis ordinibus regulating marriages among the elite classes – including both senators and equestrians, well-born individuals not directly involved in politics – and the Lex Iulia de adulteriis coercendis attempting to discourage adultery. The former, which was supplemented by the Lex Papia Poppaea in 9 CE, imposed legal disabilities upon men and women who remained unmarried during their reproductive years and rewarded parents of three or more children with benefits – preferential career advancement for men, exemption from tutelage for women. It also forbade senators and their descendants to marry freedwomen and actresses (Paulus Dig. 23.2.44 pr.) but recognized freedwomen’s marriages to freeborn men of the lower classes as valid, provided such women were not of bad character. Prostitutes could form a valid marriage only with freedmen. Bans on senators marrying freedwomen were probably not necessary, as snobbery discouraged the practice. Politicians might slander each other by alleging that their enemies were products of such mésalliances, but factual evidence to support those allegations is lacking.

The Julian law on adultery made the act of consorting with a married woman a public offense to be tried before a standing criminal court (McGinn 1998: 140–7). The husband, who was compelled to divorce his wife once he harbored suspicions of her, had the exclusive right, along with her father, to initiate a prosecution for sixty days after commission of the putative offense; after that, any qualified third party might do so. Since a successful prosecutor received a share of the property confiscated from those found guilty, both the incentive to bring an accusation and the possibility of false accusation existed. The alleged adulterer was tried first; if he was convicted, the wife was tried. Parties found guilty were both subjected to severe financial penalties and relegated to separate islands, perhaps for only a stipulated period of time. They also incurred civil disabilities: the adulterer lost his civic privileges, including the right to serve in the army; the woman involved was forbidden to remarry. There were provisions for those who took the law into their own hands. A father catching his daughter in bed with a lover either in his own house or in that of her husband could kill both offenders with impunity, even if he had previously handed his daughter over to the manus of her husband (Treggiari 1991: 282). A husband might kill a lover of low status: a slave, a freedman of the family, or someone whose profession made him disreputable, such as a gladiator or actor. Under no circumstances could he kill his own wife. Husbands also could not collude in their wives’ misdeeds: if a man knew that adultery had taken place and did not divorce his spouse and initiate a prosecution, he too could be charged with criminal conduct (Paulus Dig. 2.26.1–8).

Prior to the passage of the Julian law, accusations of adultery brought against a woman would have been dealt with by a council of kinfolk most likely composed of representatives of both families (Treggiari 1991: 267–8). The matter might have been treated leniently, since, from the offended husband’s point of view, a quiet divorce was usually the best solution. Criminalization of sexual misbehavior sought to replace flexible attitudes of family members weighing the practical consequences of various options with an uncompromising ideological rationale for discouraging marital infidelity. Giving the father permission to kill his daughter was a concession to patria potestas, but otherwise the Julian law completely removed jurisdiction over the adulteress from her family. Whether that regulation had the deterrent outcome intended is unclear. In the historical record, there are certainly numerous prosecutions for adultery, but some were undoubtedly politically motivated. Those were the sensational cases, remembered because of the prominence of the parties involved. Treggiari points out that, in comparison with other kinds of criminal accusations, the number of possible defendants was greater – men and women of all classes could be charged – and so was the pool of third-party prosecutors (1991: 298). Wealthy philanderers were doubtless the likeliest targets of accusation. The massive discussion of legal issues surrounding adultery in the writings of late imperial jurisconsults may indicate that actual trials of non-senatorial parties were common, or that the technical problems posed by the statute gave rise to an endless stream of hypotheticals.

The Julian legislation had the pragmatic corollary effect of creating a caste of sex workers (McGinn 1998: 156–71). While the respectable matron was distinguished by her costume of long robe and hair ribbons, the prostitute customarily wore a man’s toga (this cross-dressing, certainly symbolic, may mark her degraded condition as a “public” woman). Augustus’ legislation formalized the existing dress code and required the convicted woman to wear the prostitute’s garment, a stipulation that conflated adultery with venal promiscuity. At the same time, the statute defined certain groups of women as exempt from its jurisdiction: slaves, whores and madams, foreigners not married to Roman citizens, the latter because their private activities were of no interest to the state (McGinn 1998: 194–9). Later jurists placed the condemned adulteress herself in the same category. Men could have sexual relations with such women without fear of committing stuprum. However, prostitutes were obligated to register as professionals with the authorities. When Vistilia, a member of a high-ranking family, attempted in 19 CE to avoid impending prosecution by registering, the Senate closed that loophole by passing a decree that no woman of the upper classes would be allowed to prostitute herself (Tac. Ann. 2.85). “Respectable” and “non-respectable” women were not only distinguished outwardly but also legally distanced from each other by social rank.

Butchery for Fun

Studying late Republican Rome, T. P. Wiseman thinks, is “like visiting some teeming capital in a dangerous and ill-governed foreign country” because its mores were not ours. As he embarks upon an exposé of Roman brutality, he warns that what will follow “is not for the squeamish” (1985: 4–5). References to instruments of torture taken for granted in ancient sources – lashes, the rack, red-hot metal plates – are made grimmer by the awareness that such penalties were inflicted publicly, at least in the imperial era. Slaves and lower-class criminals were most liable to be tortured; by the end of the second century CE, as we will see, a formal status distinction between the “more distinguished” (honestiores) and the “less distinguished” (humiliores) exempted the former group from corporeal punishment but defined it as proper to the latter. Fear was the recognized means of keeping a gigantic slave population under control.

During the late Republic, prominent men went about with armed bodyguards, for mob violence was a frequent occurrence and dignitaries themselves shrank at nothing to maintain their honor. As for sex, Wiseman remarks, the notion that penetration involved disgrace prompted the use of sexual assault as punishment for intruders, especially adulterers, an exercise all the more humiliating if inflicted by a householder’s slaves. Suggestive images were visible everywhere: ithyphallic statues of Priapus, the garden god; lewd mimes, which upper-class women attended; semi-naked harlots in the streets (Wiseman 1985: 5–14). These observations on cruelty and sex are juxtaposed without being integrated, but the inference is plain. In a culture where sex was so unashamedly on display, where violence was accepted as routine, and where bodily penetration was synonymous with dominance, brutality may have been erotically stimulating. In fact, such a claim has been made: according to Otto Kiefer, harsh practices of educating children, dealing with women and slaves, and punishing criminals were all manifestations of a Roman will to power that turned on itself once it lost its object, the pursuit of empire, and exhausted itself in “wild orgies of sadism” at gladiatorial games (2000 [1934]: 78–9).

Kiefer’s and Wiseman’s horror is that of outsiders repelled by an unthinkable way of life. Yet escalating bloodshed in entertainment media has lately brought scholars to try to understand a seemingly comparable phenomenon, the Roman arena, “from the inside” (Kyle 1998: ix–x). Gladiatorial bouts were originally a funeral ritual presented as an offering to the dead. By the late Republic they were socially institutionalized as entertainment, termed munera (“gifts”) because they were generally sponsored by magistrates bidding for popular favor. Combatants, who walked into the arena knowing that they might well die to pleasure the crowd, became trendy celebrities. Their reputed sexiness is easily documented; graffiti from Pompeii mark the hot reputations of two local stars, Celadus and Crescens (CIL 4.4342, 4353), and Juvenal retells with relish (6.82–113) the scandal of Eppia, the senator’s wife who eloped to Egypt with her scarred and middle-aged lover Sergius – a far cry from Russell Crowe.10 “It’s the sword women love,” the satirist jeers in a not-so-subtle double entendre that actually displays considerable sociological insight (112). Rome was a warrior society in which military prowess remained vital to the notion of masculinity even after the age of the citizen-soldier was long past. Once war was “converted into a game” (Hopkins 1983: 29), the gladiator’s combat skills, bravery, and self-possession in the face of death turned him into an emblem of virility, in contrast to the aristocrat who led a sedentary and, possibly in his own eyes, ignoble life (Wiedemann 1992: 34–7; Barton 1993: 27). Even though gladiators were, for the most part, slaves or condemned criminals, it is therefore not difficult to understand why they possessed such erotic appeal. It was, however, a paradoxical sensuality because they were simultaneously regarded with profound contempt; the Christian apologist Tertullian, who inveighs against the arena in his pamphlet On Spectacles, thinks it perverse that “men hand over their souls, women their bodies” to those very persons whom they stigmatize with disrepute and loss of civic status (22.2).

What a Piece of Work Is a Man!

Cultures conceptualize masculinity along a surprisingly broad spectrum. Many books have been written, for example, on the Latin American notion of machismo, which is not easy for observers of Northern European stock to grasp. (Conversely, swarthy laborers from rural Mediterranean societies might have a hard time understanding why being labeled a “metrosexual” is in some circles a compliment.) Ancient ideas of masculinity transformed themselves in response to a changing cultural environment, as the following chapters on Rome will show. Here is a preview of what to expect.

We can start, as always, with Homer. In epic poetry, war is the activity that defines a man (Il. 6.490–3). Captains urge troops to show “manliness” (ênoreê, derived from anêr, “man”) in support of comrades, but too much individual daring (agênoriê), such as Achilles displays, is condemned because it puts fellow soldiers at risk (Van Nortwick 2008: 77). Penelope’s intrusive suitors are also characterized by agênoriê, testosterone overload, as it were (Graziosi and Haubold 2003). To classical Greek thinkers, manliness, which they call andreia (likewise from the root anêr), is a civic and philosophical virtue equated with courage and defined by Aristotle as a mean between cowardice and rashness (Eth. Nic. 1107b, 1115a). In both periods, the essence of Greek masculinity is agonistic: it involves valor in battle alongside one’s companions and competitive zeal for the esteem bestowed by the army or polis (Sluiter and Rosen 2003: 14–15).

Roman masculinity may be more complex than that, for the number of academic studies attempting to dissect it is steadily growing. In Latin the word for “manliness” is virtus. Cognate with vir, “man,” this noun, too, is regularly used of martial prowess. According to Myles McDonnell, that was, in fact, its original meaning; the ethical overtones found in the English derivative “virtue” accrued only after virtus was equated with Greek aretê, “excellence” (2006: 59–71, 105–41). Other philologists believe the word may have acquired a moral dimension at a very early stage in its history (Eisenhut 1973: 219–22). The fact that virtus is a fully adequate translation for both andreia and aretê, concepts quite separate in the Greek language, shows that its extension is somewhat elastic.

Although andreia and virtus both denote the quality essential to being a “real man,” they reflect genuine cultural differences in conceptions of gender. One notable distinction between the two is that Greeks perceived something off-key about female andreia (Goldhill 1995: 137–43), while Roman women might rightfully aspire to virtus and were praised for achieving it (e.g., Cicero speaks of his wife’s “astonishing virtus,” Fam. 14.1.1). Romans were inclined to grant their womenfolk a share in masculinity because, unlike the archaic and classical Greeks, they never saw it as something a man was born with. In the early Hellenic belief-system, as encapsulated in the Pythagorean Table of Opposites (Arist. Metaph. 986a.22–9), the antithesis of male and female was axiomatic, a fundamental polarity that could organize secondary categories of experience like right and left, hot and cold, dry and wet. Because each of those dyads consisted of a positive and a negative quality, the superior element (right, hot, dry) was assigned to the male, the inferior to the female (Lloyd 1966: 48–65). So metaphysically entrenched was this principle of gender opposition that theorists like Aristotle found it necessary to invent physiological or circumstantial explanations for the perverse “femininity” of the kinaidos. However, under the influence of the “one-sex” biological model, which gained ground, we recall, during the early Roman empire, Greek intellectuals began to regard themselves as a composite of masculine and feminine traits, either set of which might prevail regardless of anatomical sex (Gleason 1995: 58–60). They came around, in other words, to a Roman way of thinking.

Romans held manhood to be an achieved state, one the biological adult male (mas) had to attain through struggle and self-discipline before testing it on the battlefield and in the forum. Rhetorical training, with its emphasis on generating an authoritative public presence, was the vehicle for producing the vir bonus, the good man who was by definition also a good soldier and good citizen (Gunderson 2000: 7–9). What was gained at great cost to self might be readily lost, though, and was perpetually open to question. Failure and defeat impugned virility unless counteracted by a prodigious display of resolve in the face of death. “Because it did not come naturally for a male to have virtus, it was no less natural for the Romans to attribute virtus to a female, who, equally unnaturally, showed exceptional will and energy” (Barton 2001: 41). The suspicion that masculinity is persistently vulnerable accounts for the many examples of “gender slippage” that we will encounter in subsequent pages as ancient men articulated and in certain cases acted out their worst fears.

However psychologically conflicted the Romans were in their attitude toward gladiators, they felt no remorse over the slaughter of beasts or the torture and killing of felons. Scheduled in the afternoons, as the last event on the program, gladiatorial matches were preceded by trained animal shows and staged hunts of wild animals (venationes) and then by mass executions that served up the deaths of the condemned as a diversion.11 In contrast to gladiators, who offered spectators a model of fortitude with which they might identify, hunts and executions were one-sided demonstrations of Roman might and authority. There is no way to determine an accurate body count of victims, animal and human, killed in this fashion, but recorded totals are shocking (Kyle 1998: 76–9). Animals perished in the greatest numbers.12

Emperors reaffirmed the power of empire by exhibiting creatures imported from remote provinces and manifested their own generosity through the destruction of costly specimens. Victories of hunters over ferocious beasts demonstrated human mastery of nature (Wiedemann 1992: 55–67). Insofar as watchers in the amphitheater felt themselves distanced as a species from the creatures on the sand below, they experienced no pathos in their suffering (Brown 1992: 207–8). Punishments of criminals, involving both extreme pain and degradation, were used as deterrents and also looked upon as a restoration of social order, for the wrongdoers suffered in proportion to the injuries they had committed. The Roman spectator did not regard them as proper objects of sympathy either, because human offenders, like predatory animals, were viewed as potential threats to the community as a whole. In each case, there was a clearly articulated rationale of expediency for the death meted out. We should distinguish, then, between the callousness toward putatively deserved suffering shown even by the educated upper classes and a sadistic delight in inflicting suffering on the undeserving, which Roman upper-class morality rejected (Lintott 1999: 44, 50–1).

From a self-justifying position of ethical superiority, elite authors do ascribe a sordid bloodlust to the masses. Petronius makes one of his municipal freedmen characters, anticipating a coming show enthusiastically, say of the donor: “He will provide a first-class contest, fights to the death, with the butchery in the middle so the amphitheater can see it” (Sat. 45.6). In a letter to his student Lucilius (Ep. 7.2–4), the philosopher Seneca charges that attending executions in the arena blunts moral sensitivity because the barbarity of the multitude is infectious. When he went there at midday hoping for some relaxation, he says, he was exposed instead to “pure slaughter” (mera homicidia), men without protection forced by attendants to slay each other with the audience urging them on: “Kill him, whip him, burn him!” Most viewers prefer that kind of thing to regular gladiatorial matches and specially arranged bouts, he adds, because they are not interested in skill but revel in carnage for its own sake.13 Such cruelty was believed to be instantaneously addictive. Augustine, bishop of Hippo and major Christian theologian, recalls that his young friend Alypius, while studying law at Rome, was hauled off to the arena by acquaintances despite his protests. At first he refused to watch, but when the crowd roared and he opened his eyes, overcome by curiosity, he was transfixed: “when he saw that blood, he at once drank in the brutality, and did not turn away but trained his eyes on the sight, and swallowed madness without knowing it, and was excited by the intensity of the contest and inebriated with bloody pleasure” (Conf. 6.8). From that time on, Augustine testifies, he became a passionate fan of the games.

How can we account for the Romans’ pleasure in witnessing the inflicting of pain? One current explanation views gladiatorial spectacles as “a ritual of empowerment” (Barton 1993: 35). Rooting for the underdog was not a Roman tradition; audiences preferred the psychological security of locating themselves on the winning side. Besides reaffirming collective order, punitive action against outlaws and beasts assured even the socially marginal of their superiority to such “others.” Compensatory violence was thus an outlet for the frustration experienced by subjects of an increasingly more autocratic and oppressive government (Futrell 1997: 48–9). Gladiatorial shows, furthermore, functioned as political theater. With the emperor watching, citizens might engage in mass demonstrations against individuals or public policies; audiences would also be flattered by an emperor’s efforts to solicit their goodwill (Hopkins 1983: 14–20; Gunderson 1996: 126–33). Finally, decisions about whether a defeated gladiator would live or die were determined by the attitude of the crowd. In a collective act nostalgically reminiscent of its vanished political sovereignty, the assembled populace could grant life to a game but defeated fighter and freedom to an impressive one (Wiedemann 1992: 165). Self-respect was accordingly purchased at the cost of others’ agony, and gratification followed in its wake.

Explaining the popularity of the games as being due to their unique cultural operations within Roman society is attractive because it treats audience demand for violent spectacle as a historically contingent phenomenon divorced from present-day reality. In contrast, one new investigation, while acknowledging the validity of a culturally specific approach, draws upon social psychology to stress the similarities between the arena and other cross-cultural instances of collective bloodlust (Fagan 2011). Public executions, often involving torture and protracted suffering on the part of the victims, attracted great crowds in Europe, Britain, and the United States until the mid-nineteenth century; extreme combat sports in which participants risk serious injury have their eager followers even today. Though dog fighting is illegal in the USA, it is widely practiced throughout the country in conjunction with other forms of criminal conduct; in Hispanic societies the bullfight is a communal ritual, with bull rings located in all major cities (used, however, for a variety of events—see Fig. 7.2). As students of history, we may disapprove of the following the games enjoyed in the Roman world, but as students of human behavior we should recognize that many of the satisfactions they provided are today furnished by related forms of mass entertainment, from summer blockbuster action films to the Super Bowl.

Conclusion

This chapter has attempted to identify some of the idiosyncratic features of Roman sexuality, compared with Greek and, to a certain extent, Etruscan notions of eroticism. Like classical Athenians, the Romans conceptualized sex as a hierarchical relationship in which the male penetrator assumed the dominant role. However, they aligned this construction of sex with an intricate system of social relations in which the ascendancy of the free person over slave or former slave, rich over poor, well born over base, and even man over woman did not always line up as neatly in practice as such inequalities should have done theoretically. They also imposed strict sanctions on violating the integrity of a citizen youth and laid the blame for adultery on the errant wife, not her lover, defining it as a matter of civic concern even more than family honor. If Seneca and other witnesses are telling the truth, they were mesmerized by the spectacular brutality of the arena and took a sadistic delight in the terror and suffering of those slain. Such factors are enough to ensure the distinctiveness of Roman sexual protocols. Yet this does not mean that Roman mores were not deeply colored by Hellenic thinking, or even vice versa: introduced into the Greek East, gladiatorial games and beast-hunts became as popular as they were in Italy.

From the second century BCE onwards, wealth had been flowing into Rome from its conquered territories. Social change, inevitable under the circumstances, was blamed by Roman authors on exposure to Greek decadence, and, more immediately, on the selfish choices of individuals stemming from an unmanly lack of self-discipline. Disquiet over late first-century BCE unrest took the form of jeremiads against a perceived epidemic of luxurious living. No attempt was made to distinguish among the immoral behaviors practiced by the hedonist – the man guilty of one was presumably guilty of the rest as well (Corbeill 1996: 128–73). Accusations of squandering money are accompanied by charges that the offender has likewise been dancing and singing, feasting sumptuously, getting drunk, committing adultery, and playing the passive role in homoerotic coupling, vices linked together in a metonymic chain because each one was connected to an overabundance of wealth. Fantasies of criminal copulation and bizarre departures from gender roles were a natural outgrowth of the notional integration of sexuality, dominance, and social rank.

Discussion Prompts

1. Democratic systems in contemporary first-world countries laud individual attributes such as talent and determination when explaining academic, vocational, athletic, or artistic success. Elite young Roman men instead relied greatly on personal connections as they launched political or military careers. Why was patronage such a critical factor in Roman society as opposed to our own?

2. Roman moralists blamed the wickedness they observed on exposure to Greek customs, especially those of the Eastern Mediterranean. Projecting negative qualities on members of another class, ethnic group, or religion in order to hold them responsible for perceived social ills is, according to many psychologists, a defense mechanism by which we avoid confronting our own weaknesses. What does the tendency to fault Greeks for luxurious living suggest about Roman ambivalence regarding wealth and its uses?

3. The Julian laws regulating marriage, encouraging childbirth, and imposing sanctions on adultery have been described by ancient historians as an unprecedented intrusion of government into the private sphere. What features of Roman culture as described in this chapter would render such legal intervention possible, if not palatable? In other words, where did the Romans draw the line between strictly personal interests and those of the state? Do current-day social conservatives operate from the same general premises?

4. When discussing the popularity of beast-hunts and gladiatorial matches, we surveyed attempts by scholars to show how those particular pastimes met Roman cultural needs. Using the same method of inquiry – investigating how entertainments respond to audience fantasies and desires – explain the psychic attractions of summer action flicks, particularly franchises repeatedly involving the same cast of good guys in roughly the same predictable set-up.

Notes

1 The Lupercalia, held on February 15, was closely connected with the legend of the she-wolf who suckled the twins Romulus and Remus (Ov. Fast. 2.381–424). Following the sacrifice of a goat to a divinity (variously designated as Faunus or Lycaean Pan), naked young men ran about the Palatine striking whomever they met, especially women of childbearing age, with thongs made from the skin of the goat. Although the celebration itself was thought to date back from before the founding of Rome, the rite of flagellation was introduced in the third century BCE in response to an epidemic of miscarriages (Liv. fr. 63 Weissenborn = Wiseman 1995: 19 no. 13).

2 How large were Athens and Rome, comparatively? Herodotus (5.97.2) gives a figure of 30,000 Athenian male citizens in the early fifth century BCE. If we multiply by four to account for wives and children, we get a total citizen population of 120,000 plus slaves and metics. Some doubt that the population of Athens was that high. According to the emperor Augustus’ head counts for recipients of money and wheat distributions (Aug. RG 15), approximately 250,000 male Roman citizens received allotments on five occasions between 44 and 12 BCE; the number rose to 320,000 in 5 BCE, then sank to 200,000 in 2 BCE. Those rapid fluctuations must reflect variations in accounting procedure rather than actual population shifts. Estimating numbers of women, children, resident aliens, soldiers, and slaves, Hopkins (1978: 96–8) arrived at a total of 800,000 to one million during the reign of Augustus, a figure now widely accepted (Scheidel 2001: 51). The quick and dirty answer, then, is that Augustan Rome was three to four times larger than classical Athens.

3 An example is the prominent noblewoman Caecilia Metella, who in 80 CE arranged for Cicero, then beginning his oratorical and political career, to defend her hereditary client Sextus Roscius on a charge of murdering his father (Cic. Rosc. Am. 27). See Dixon (1983).

4 Before Dover’s and Foucault’s work altered scholarly thinking, confusion frequently resulted from the mistaken categorization of pederasty or passivity (or both) as “homosexuality.” For example, Boswell (1980: 87) concludes a survey of evidence for homoerotic practices in Rome with the contention that “none of its laws, strictures, or taboos regulating love or sexuality was intended to penalize gay people or their sexuality … they were fully integrated into Roman life and culture at every level.” By imposing a modern cultural category on sexual acts in Latin texts, he arrives at the misleading generalization that Rome, in contrast to Christian Europe, was “tolerant” of gay persons as a minority group.

5 In his treatise On Agriculture, Cato advises farm owners to sell off old and sick slaves along with other superfluous chattels (2.7). This counsel prompts an extraordinary outburst of disapproval from his Greek biographer Plutarch, who condemns it as inhumane and protests that one should not behave so callously even toward animals, though he ends by saying that readers must make up their own minds about that side of Cato’s character (Cat. Mai. 4–5). Defenders would argue that the censor’s ostentatious frugality was a reproof to the profligacy of his contemporaries.

6 Cf. Helv. 19.2, where Seneca also acknowledges his aunt Marcia’s role in obtaining his quaestorship. The line between proper intercession and undue interference in public affairs was, as Dixon (2001: 103) remarks, “all a matter of perspective.”

7 A popular mime, whose plot was apparently well known, involved a dapper adulterer, a clever wife, and a foolish husband. Ovid, exiled for having written the “immoral” Art of Love, reminds Augustus that he had sponsored this no less risqué skit at his own games (Tr. 2.497–516). In one stock scene, to which both Horace (Sat. 2.7.59–61) and Juvenal (6.42–4) allude, the lover is hidden in a chest when the husband returns home unexpectedly. The mockery directed at him implies that in a real-life situation a deceived husband might also incur ridicule.

8 Strictly speaking, under Roman law a child was illegitimate only if he or she was not born of a valid Roman marriage; such children had no legal father and took their status (slave or free) from that of their mother (Paulus Dig. 2.24.1). If a child was born to a woman who was married, her husband was considered the father unless he refused to recognize the child as his own. There are actually relatively few surviving jokes about someone’s paternity, although Cicero, whose wit could be tactless, is credited with a pair (Plut. Cic. 25.4, 26.6). It is important to recall that in classical Athens biological paternity was not a joking matter.

9 Cicero, whose financial position was often overextended, worried about decisions made by his wife Terentia regarding her holdings but could do nothing except plead with her (Fam. 14.1.5).

10 Classicists, for their part, recount with equal relish that, when the armory of the gladiatorial barracks at Pompeii was excavated, archaeologists found eighteen skeletons, including one of a woman wearing considerable gold jewelry and an emerald necklace and carrying a cameo in a casket (Mau 1982 [1902]: 163). Innocent explanations are seldom proposed, although there might well be one: it seems unlikely that a rich lady would wear all her valuables to a tryst with her boyfriend in a barracks while a volcano was erupting.

11 We have abundant testimony to the attraction of “fatal charades” in which criminals done up as mythological heroes suffered the hero’s fate: a man costumed as Hercules, for example, might be burnt alive (Lucill. Anth. Pal. 11.184; Tert. Apol. 15.5). Coleman explains the psychological appeal of viewing such executions as a combination of righteous interest in justice, horror, the element of unpredictability when a beast was employed as the means of destruction, and a morbid fascination with the actual moment of death (1990: 57–9).

12 Kyle confronts the gruesome practical question of how “literally tons of human and animal flesh” (1998: 159) were disposed of. Gladiators who died well might be provided with decent burial, although some public cemeteries debarred them (1998: 160–2). During the Republican period, carcasses were dumped into pits on the Esquiline Hill, but the practice would have ended when the area was reclaimed and turned into a pleasure garden by Augustus’ advisor Maecenas (1998: 164–8). Animal remains, Kyle suggests, were distributed to the populace as meat (1998: 190–4) and the corpses of criminals were thrown into the Tiber, because water would flush away the pollution of death, while the body was insulted by being denied burial (1998: 213–28).

13 Seneca’s many references to the technicalities of gladiatorial combat indicate that he attended the games regularly and appreciated the expertise displayed by a well-matched pair of opponents (Wistrand 1992: 20; Cagniart 2000: 609). His interest in gladiatorial combat as sport was not incompatible, it appears, with his professed Stoic reverence for human life.

References

Barker, G. and Rasmussen, T. 1998. The Etruscans. Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Barton, C. A. 1993. The Sorrows of the Ancient Romans: The Gladiator and the Monster. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

—— 2001. Roman Honor: The Fire in the Bones. Berkeley and London: University of California Press.

Bonfante, L. 1986. “Daily Life and Afterlife.” In L. Bonfante (ed.), Etruscan Life and Afterlife. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. 232–78.

—— 1996. “Etruscan Sexuality and Funerary Art.” In N. B. Kampen (ed.), Sexuality in Ancient Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 155–69.

Boswell, J. 1980. Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brendel, O. J. 1970. “The Scope and Temperament of Erotic Art in the Greco-Roman World.” In T. Bowie and C. V. Christenson (eds.), Studies in Erotic Art. New York: Basic Books. 3–107.